Abstract

Banking scandals, accounting fraud, product recalls, and environmental disasters, their associated reputational effects as well as company response strategies have been well reported in the literature. Reported crises and scandals typically involve one focal company for example BP and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon accident. As business practices change and company supply chains become more complex and interlinked, there is a greater risk of collective crises where multiple companies are associated with the same scandal. We argue that companies are likely to behave differently in a group setting compared to when faced with a crisis individually. Using an inductive approach, we examine the case of the Rana Plaza building collapse. We find that organizations with a history of similar crises adopt defensive strategies and communicate much later compared to organizations which adopt accommodative strategies. Contrary to the individual case, in a collective crisis accommodative strategies result in more negative reputational damage and a higher burden of responsibility. We propose that the relationship between crisis response strategy and organization reputation is moderated by the crisis setting. We extend the logic of crisis management and corporate reputation to incorporate the case of a collective crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Banking scandals and malpractices, product recalls, labor exploitation, or accidents resulting in severe industrial pollution have led to ever-increasing public interest in the ethical conduct and corporate social responsibility (CSR) of business. The literature outlines how companies embroiled in ethical, environmental, or product harm crises have experienced reputational consequences (Beder 2002; Balmer et al. 2011; Firestein 2006) which can also result in financial implications. To what extent a crisis affects the reputation of an organization depends on several factors. These include the type and scale of the crisis (Laufer and Coombs 2006) as well as how responsibility for the crisis is attributed (Coombs 2007b). The history of the organization in terms of its involvement in previous crises along with the reputation of the company prior to the crisis is also an important consideration (Coombs 2006; Laufer and Coombs 2006). The media can also play an important role both in terms of media visibility (Fombrun and Shanley 1990) as well as media framing (Entman 1993; Scheufele 1999). Companies which are visible in the media are likely to face a greater threat to reputation as they are those which are ‘top of the mind’ in terms of public awareness (Carroll 2004; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Media framing refers to how the story is conveyed by the media and this can be particularly important in terms of attribution of responsibility in times of crisis (An and Gower 2009).

It is also clear from the literature that companies are concerned with minimizing any negative effects on reputation following corporate crises and scandals (Laufer and Coombs 2006; Sims 2009; Coombs 2007b) and various crisis response strategies have been prescribed (Coombs and Holladay 2002; Coombs 2007b; Claeys et al. 2010). Some scholars advocate that companies should adopt accommodative strategies and so accept responsibility and compensate victims (Benoit 1997), while others adopt the view that the organizational response should be in line with the reputational threat. From this perspective, more accommodative strategies are required only where the threat to reputation is high (Coombs and Holladay 2002).

To date, crises researched in the literature have concentrated primarily on those involving one or at most two companies. For example, the Enron Corporation scandal was centered around Enron and its accountancy firm, Arthur Anderson (Firestein 2006). The Merck and Co., Vioxx scandal involved only the Merck pharmaceutical company (Cavusgil 2007), while the Deepwater Horizon explosion centered around BP and, to a lesser extent, the offshore drilling services company, Transocean (Harlow et al. 2011). Thus, what is known about corporate reputation in times of crisis is centered largely on those crises where a single or at most two companies are involved.

However, as business practices change and companies move their manufacturing activities from wholly owned facilities to supplier-based manufacturing often far from company headquarters (Lindgreen et al. 2009), the issue of collective crises is likely to become more prevalent. In a collective crisis, there will be multiple companies associated with the same scandal. An example of a recent collective crisis is the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh. More than eleven hundred garment workers lost their lives with a further twenty-five hundred injured in one of the deadliest industrial accidents. Factories in the collapsed building manufactured clothing for up to thirty major global fashion retailers (Foxvog et al. 2013). In another 2013 incident, beef products found to contain horsemeat were sold across Europe implicating multiple actors including meat suppliers, food manufacturing companies, retailers, and restaurants. The horsemeat scandal once again highlights how the supply chains of companies are interlinked and so multiple companies became associated with the scandal.

We argue that organizations are likely to react differently to a crisis in a collective setting compared to in an individual setting. Due to diffusion of responsibility, organizations may feel less responsibility in a collective crisis and less urgency to react. Organizations may also ‘wait and see’ the reactions of other companies involved and crisis response strategy might be influenced by the actions of others.

In this paper, we aim to extend the literature on corporate reputation and crisis management to the case of a collective crisis. We aim to develop positive theory around how companies are likely to react to and respond in a collective crisis and how this will impact corporate reputation. We adopt an inductive approach using case studies. Taking the case of the Rana Plaza building collapse, we examine eight of the companies involved in this crisis. We gather data from a variety of sources including company websites and corporate social responsibility reports, company Twitter accounts, company press releases, newspaper articles, reports by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the websites of groups involved in repairing the damage post-crisis (for example, the Rana Plaza Donors Trust Fund and the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety). We analyze the data using an inductive approach. Considering post-crisis response strategy, we find that organizations with a history of similar crises adopt defensive strategies and communicate much later compared to organizations which adopt accommodative strategies. We offer a refinement to the current accepted thinking in the crisis management literature that accommodative strategies reduce damage to reputation. In a collective crisis, we find that accommodative strategies result in more negative reputational damage, a higher burden of responsibility, and a higher price paid post-crisis. Given this, we propose that the crisis setting, individual or collective, acts as a moderator for the relationship between crisis response strategy and organization post-crisis reputation. We extend the logic of crisis management and corporate reputation to incorporate the collective crisis case.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we outline the individual versus collective setting for a corporate crisis. This is followed by a review of the corporate reputation literature focusing on crisis management. In the methodology section, we describe our adopted approach, the crisis case, firm selection, and data collection and analysis. We then describe our findings, develop propositions, and present our theoretical model. We discuss the results’ contributions and future avenues for research. We then provide overall conclusions. Limitations of the research are outlined in the final section.

Crisis Setting: The Individual Versus Collective Setting for a Corporate Crisis

A corporate crisis has been defined as “a low-probability, high-impact event that threatens the viability of the organization and is characterized by ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decisions must be made swiftly” (Pearson and Clair 1998, p. 60). In this paper, we differentiate between an individual and a collective crisis setting. We identify ‘individual’ crisis settings as those where the controversy revolves around a single company. Some of the most significant individual crises reported in the literature include the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the Tylenol product tampering case, and the chemical release at Bhopal (Pearson and Clair 1998). In a ‘collective’ crisis, multiple organizations are associated with the same crisis. For example, twenty-eight fashion retailers were associated with having products manufactured in the Rana Plaza building which collapsed in April 2013. In such crises instead of one focal organization, the controversy revolves around many different organizations. We argue that the collective crisis setting may have a different dynamic in terms of how individual companies respond to the crisis.

The social psychology literature shows that individual behavior is influenced by the presence of others. The bystander effect is a well-established phenomenon in this literature (Darley and Latane 1968; Garcia et al. 2002). The bystander effect shows that people are much slower and less likely to help someone in distress when they are aware that there are other witnesses, compared to if they were faced with the incident alone (Garcia et al. 2002). One well-known case is that of the murder of Kitty Genovese in a residential street in New York. In this case, thirty-eight people witnessed the attack and murder but none intervened (Darley and Latane 1968). One explanation for this phenomenon is diffusion of responsibility (Darley and Latane 1968; Garcia et al. 2002; Barron and Yechiam 2002). Diffusion of responsibility posits that in emergency situations people are less likely to help when there are others present as they feel a reduced sense of responsibility and accountability since they know that others are capable of responding (Garcia et al. 2002; Darley and Latane 1968). This effect has been found to be more pronounced the larger the group of bystanders (Darley and Latane 1968). Social influence is also an important factor. If other witnesses do not appear to consider an event as an emergency, then this apparent consensus could lead the bystander to draw the same conclusion so may not react to the situation (Bickman 1972). The notion of being part of a group is consistent with ‘getting lost in the crowd,’ having a reduced sense of accountability and responsibility (Garcia et al. 2002) and being influenced by the reactions of other members of the group.

The above studies consider the likelihood that individuals will adopt prosocial behavior and help others in emergency situations. There are clear differences between how individuals react when they are faced with an emergency alone compared to when they are faced with an emergency in a group situation. Likewise, in the case of organizations it could be reasonably expected that the collective setting will influence when and how individual companies respond to a crisis. Organizations may feel less responsibility for the crisis and less urgency to react in a collective setting. They may wait to gauge the reactions of other companies involved before adopting a position post-crisis. How organizations react and manage a collective crisis is likely to be different compared to how they react to an individual crisis. Given that the company response post-crisis can influence organizational reputation (Coombs 2007b), the reputational effects of individual companies in a collective crisis case are likely to differ from the individual crisis case and this is what we aim to investigate. In the next section, we consider the extant literature on corporate reputation and crisis management.

Corporate Reputation: A Review of the Literature

Organizational and Collective Reputation

There is a general consensus in the literature that reputation is valuable to a company. A favorable corporate reputation can attract the best talent and can lead to higher returns as companies with good reputations can charge premium prices and can be more attractive to investors (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Helm 2007). Reputation can differentiate a company from its competitors (Hall 1992). Barnett et al. (2006, p. 34) define reputation as “observers collective judgments of a corporation based on assessments of the financial, social, and environmental impacts attributed to the corporation over time.” This definition is consistent with the notion of reputation as a multidimensional concept (Deephouse 2000; Deephouse and Carter 2005) and, as such, economic as well as non-economic criteria are used to assess and evaluate firms (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Given that companies have a broad range of stakeholders, evaluation criteria will depend on the priorities of particular groups. Financial success is one element of corporate reputation, but stakeholders also use signals such as market performance and market risk, institutional ownership, dividend policy, strategic positioning, media visibility, and product quality as well as social and environmental responsibility to assess reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Brammer and Millington 2006; Brammer and Pavelin 2006; Russo and Fouts 1997).

Context is also important for reputational judgement (Barnett and Hoffman 2008). The actions of an organization may be judged relative to its prior actions and so history affects stakeholders’ current perceptions (Barnett 2007a). Extant literature shows that the reputation of the firm may also be impacted by its competitive and institutional environment. This is consistent with the notion of collective reputational effects or reputation commons (Barnett and Hoffman 2008; King et al. 2002; Winn et al. 2008; Fauchart and Cowan 2014). Collective reputation posits that the reputation of the individual company depends not only on its actions but also on the actions of industry peers. This effect has been observed in industries such as the chemical industry and the oil and gas industry in the aftermath of disasters such as Bhopal and Exxon Valdez (Barnett and Hoffman 2008; Bertels and Peloza 2008; King et al. 2002). Negative events can result in a reputation spillover where the reputations of similar companies in the same industry sector are also tarnished even if they were not involved in the disaster (Yu and Lester 2008). Competitive as well as collective reputation management strategies may be used to restore industry-wide reputation in the aftermath of a serious crisis (Winn et al. 2008).

In the case of collective reputation, authors deal with the reputational effects of crises on innocent companies in the same industry sector, in other words organizations not directly involved in the crisis. While Kayser (2014) considers a reputational commons problem associated with the Rana Plaza building collapse, we extend the logic of the collective case to a ‘collective crisis’ and consider the case of multiple ‘guilty’ organizations rather than innocent bystanders.

Corporate Reputation in Times of Crisis

Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) offers a framework to predict the reputational threat posed by a crisis and recommends crisis response strategies (Coombs 2007b; Coombs and Holladay 2002; Claeys et al. 2010). According to this literature, there are factors which determine how a particular crisis is likely to impact company reputation. The type of crisis and the severity of the crisis are important factors. Where an incident has a more severe outcome, with serious injuries or deaths, then it is likely that stakeholders will attribute more blame to those deemed responsible (Laufer and Coombs 2006). The more responsibility for a crisis that is attributed to an organization then the stronger the negative feeling towards that organization and so greater the threat to reputation (Coombs and Holladay 1996). The SCCT literature identifies three clusters of crisis type each with different attributions of responsibility and reputational threat (Coombs 2007b). The victim cluster, where the organization is also deemed to be a victim (natural disasters or workplace violence), has weak attributions of crisis responsibility and the reputational threat is mild. The accidental cluster, where actions leading to the crisis were accidental (technical error or accident), has minimal attributions of crisis responsibility and so a moderate reputational threat. The intentional cluster, where the organization intentionally put people at risk, has very strong attributions of crisis responsibility and so a severe reputational threat (Coombs 2007b). In the case of a crisis especially a severe one, the public will evaluate the cause of the crisis and company responsibility (Coombs and Holladay 1996). Prior reputation of the company as well as crisis history is also important (Coombs 2007b). According to Coombs (2007b, p. 137) “either a crisis history or a negative relationship/history prior reputation will intensify the reputational threat.” This is also in line with the idea that past organizational performance influences reputation (Barnett 2007a).

Since stakeholders do not have full information about company activities, the media is one of the main ways that the public are informed (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Deephouse 2000). In a crisis situation, the media is often the means by which the misconduct becomes visible to society (Sims 2009) and so is important in informing stakeholder judgements.

Reputation and the Media

The media is an important channel for conveying information about organizational activities. For example, news about labor conditions in factories used by Nike were first reported by the New York Times (DeTienne and Lewis 2005). Fombrun and Shanley (1990) found that media visibility negatively influences reputation, even where media visibility is non-negative. Carroll (2004) showed that companies which are reported in the news are those which are ‘top of mind’ in terms of public awareness. Moreover, there is a correlation between news coverage on the attributes associated with a firm and those attributes used by the public to describe the reputation of a company (Carroll 2004). This is in line with media agenda setting effects, which posits that issues discussed in the media influence the salience of topics on the public agenda (McCombs and Reynolds 2002; McCombs and Shaw 1972; Einwiller et al. 2010).

Meijer and Kleinnijenhuis (2006) used media agenda setting and ownership theories to examine whether the reputations of companies were linked to media coverage. The authors found that news coverage about a certain issue increased the salience of the issue and the likelihood that the public would associate this attribute with the particular organization. In a more recent study, Einweiller et al. (2010) show that stakeholders attach importance to different aspects of a company’s reputation depending on personal interest. The authors use media system dependence theory to demonstrate that stakeholders rely heavily on the media as a source of information on social responsibility issues and conclude that the way in which social responsibility issues are covered by the news media ultimately influences stakeholder evaluation of the company.

The speed and efficiency of the internet means that the news and information can be communicated on social media sites such as Twitter before it is covered by traditional mass media journalists (Castelló et al. 2013). However, many traditional newspapers also use social media sites and this affords them the opportunity of tweeting online articles even before these may appear in print. A 2014 study by the Pew Research Centre has found that many people repeat tweets from major news outlets (Smith et al. 2014). Utz et al. (2013) found that people are more likely to share news from online newspapers rather than blogs showing that traditional newspapers remain important in terms of being a credible source of independent information. Therefore, we argue that the media agenda setting effect of traditional newspapers remains important even as communication via the internet and social media has evolved.

In times of crisis, the media can play a particularly important role through framing. Media framing affects public perception (Scheufele 1999; Semetko and Valkenburg 2000). Entman (1993, p. 52) defines media framing as follows: “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation” [original in italics]. A number of typical media frames have been identified in the literature. These include the attribution of responsibility frame, the conflict frame, the human interest frame, the economic consequence frame, and the morality frame (Semetko and Valkenburg 2000). In the case of communication of crises by the news media, one of the most important frames is attribution of responsibility. Within this frame, the media may present problems and their solution either at the level of the individual or the level of society. Choosing at which level the problem occurs or could be solved means that the media can also shape public opinion about responsibility for the problem. An and Gower (2009) found that the attribution of responsibility frame was the predominant one used in crisis news coverage. The type of media frame also varies depending on the type of crisis. The attribution of responsibility frame was more frequently used for preventable crises rather than accidental or victim crises. It also was found that for accidental crises the media focused on the organizational level of responsibility rather than on the individual level (An and Gower 2009).

In an individual crisis, there is generally one clearly defined company on which media attention can be focused. However, in a collective crisis the situation is more complex. As argued by Bundy and Pfarrer (2015), a crisis is an individuating event and stakeholders will attempt to associate a crisis with an individual organization. Similarly, in the collective case, it is likely that stakeholders will try to identify the individual organizations involved. From the literature, it has been established that media visibility for companies is generally scarce (Carroll 2004) so in a collective crisis it is unlikely that the media will give equal attention to all involved companies. It is not clear which companies are likely to be most visible in a collective crisis and what factors might influence media visibility. Those companies which are most visible will be those which the public directly associates with the crisis and so may suffer most negative reputation. In a collective crisis, due to the complexity and number of companies involved, it may even be less clear to stakeholders which organizations are responsible. Media framing of crises will be particularly important for stakeholder interpretation. Understanding how the media frames the crisis, attributes responsibility, and focuses on involved companies is likely to have reputational consequences for the individual companies involved in a collective crisis.

Rebuilding Reputation: Crisis Management Strategy

In the aftermath of an organizational crisis, “redressive action” (Sims 2009, p. 456) must be taken by the company where there is an effort to limit the impact of the crisis. Redressive actions taken by companies to restore reputation in the aftermath of ethical scandals have been described in the literature (Benoit 1995; Heugens et al. 2004; Sims 2009; Coombs 2007b). Sims (2009) summarizes the reputation rebuilding process in two steps, short-term actions and longer term actions. Short-term action involves dealing with the direct consequences of the event and is described by Sims (2009, p. 464) as follows: “apologizing, decoupling, and justifications are all short term solutions to address the immediate effects of a significant threat to corporate reputation.” Companies may also implement longer term actions which ensure that such an event cannot reoccur. Longer term actions may include financial compensation, employee training, or implementing company policies (Sims 2009).

Short-term crisis response strategies are also described in terms of how much responsibility the organization accepts for the crisis and a response strategy continuum has been described (Coombs 1998, 2007b; Kim and Yang 2009). The continuum ranges from defensive to accommodative strategies. Defensive strategies involve vehement denial of involvement in the crisis and so no acceptance of responsibility. Accommodative strategies result in full apology and mortification and so acceptance of responsibility. Between these extremes, companies may neither fully accept nor deny responsibility and strategies include offering excuses, providing justification, or implementing corrective actions. These strategies are in line with the image repair strategies described by Benoit (1995) which include denial, evasion of responsibility, reduction of the offensiveness of the act, corrective action, and mortification.

There is some disagreement in the literature as to the most appropriate strategy for organizations to adopt post-crisis. Accommodative strategies are most effective in terms of reducing the negative effect created by the crisis (Coombs 2007b) and also most appropriate to rebuild reputation after a crisis (Benoit 1997). Rather than employing an entirely accommodative strategy, the SCCT literature advocates that crisis management strategies should be tailored according to the reputational damage a crisis is likely to inflict. Taking into account the type and severity of the crisis, prior history, and reputation, SCCT advocates that crisis managers then choose the appropriate strategy. Only where there is more reputational damage, stronger accommodative strategies are required (Coombs and Holladay 2002). Past crisis history is a factor which can intensify reputational threat. Involvement in several crises suggests that the company has an ongoing problem which needs to be addressed (Coombs 2007a). The reputation of a company with a poor crisis history is expected to be more negatively affected. At the same time, those with a better prior reputation are expected to also have a better reputation post-crisis since they have more reputation capital and this can act as a buffer or ‘a halo’ against reputational loss (Coombs and Holladay 2006). Given this argument, companies with a poor crisis history should adopt more accommodative strategies post-crisis due to the higher reputational threat. A separate argument in the literature posits that stakeholders may have higher expectations from organizations which have better reputations (Rhee and Haunschild 2006; Bundy and Pfarrer 2015; Decker 2012). A crisis situation may result in a violation of expected standards and so better reputation can be an organizational liability. Bundy and Pfarrer (2015) examine the role of organization social approval as both an outcome and antecedent of stakeholder’s perception of a crisis. The authors propose that organizations with a higher social approval (better reputation) or a lower social approval (worse reputation) at the onset of a crisis will accept less crisis responsibility. Thus, companies with a better prior reputation will want to protect their reputational capital, while those with a poor prior reputation will want to avoid further disapproval. While there are varying viewpoints in the literature on the most appropriate post-crisis response strategy, there is general agreement that more accommodative strategies minimize reputational damage.

We can summarize that the current literature focuses either on individual companies or on collective reputation, referring to negative reputational spillovers to other industry participants. We extend the logic of the collective case to the collective crisis, where multiple ‘guilty’ companies are associated with the same crisis. In line with extant research on individual crises, factors such as crisis severity, responsibility, and past crisis history are expected to influence reputation in the collective case. However, in a collective crisis there may be a diffusion of responsibility among organizations. Individual companies may feel less responsible knowing that other organizations are available to react. There may be a feeling of ‘getting lost in the crowd’ or waiting to see how others react. This can influence the speed of reaction post-crisis, the strategy adopted and ultimately the reputational impact. In the next section, we examine the cases of eight companies involved in a collective crisis, namely the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse.

Methodology

Our study aims to develop new theoretical insights into the issue of corporate reputation in the context of a collective crisis. We use case studies and follow the approach described by Eisenhardt (1989, 1991) for theory building from cases. Case studies which link with reality are a good way to permit the development of theory which is testable, relevant, and valid (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). For our qualitative study, we choose the case of the Rana Plaza building collapse and within this we focus on the cases of eight companies linked with this crisis. Considering multiple companies within this crisis allows us to determine whether an emergent theme is replicated and also to facilitate theoretical elaboration (Eisenhardt 1991; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). Using this approach, we look at the case of each company individually and then look at comparison across cases. Prior to describing company selection, the data collection and analysis process, we give an overview of the accident at Rana Plaza.

Description of the Crisis

The Rana Plaza building collapse of April 2013 was the largest garment factory accident to date in Bangladesh and one of the world’s worst industrial disasters. The various harrowing accounts and appalling photos of the tragic event and aftermath of the collapse were documented in the media and on the websites of various NGOs and lobby groups. The Rana Plaza complex, located in the Savar area of Dhaka, consisted of an eight-story building accommodating apartments, shops, banks, and five garment factory units. Various reports suggested that additional floors had been added to the complex without the required permits. The day prior to the collapse, the building had been evacuated following the discovery of cracks; however, factory workers were told to return to work the following day. On April 24, the building collapsed killing more than eleven hundred people and injuring over twenty-five hundred, many of whom were left with permanent injuries and disabilities. The rescue operation lasted 19 days and the rescuers consisted of volunteers as well as emergency service workers who risked their own lives as the remains of the building continued to move and fires broke out in the debris. Clothing labels and paper work were found in the rubble linking approximately twenty-eight international buyers and fashion brands to the garment factories in Rana Plaza (Foxvog et al. 2013; Clean Clothes Campaign 2013).

According to the categorization in the SCCT literature, this crisis fits into the “accidental” cluster (Coombs 2007b) as the harm caused is unintentional. According to the literature, for this type of crisis the attribution of blame will be minimal and the ensuing reputation threat moderate (Coombs 2007b). However, the severity of the crises also influences the reputational threat (Laufer and Coombs 2006). In this case, there were a large number of victims including those who died and those left with severe injuries. Given this, we argue that the reputational effect of Rana Plaza for the companies linked with the crisis was at least moderate but could potentially have been bordering on severe.

Company Selection

A theoretical sampling approach was used to determine the companies for inclusion in the analysis. Since the aim of our study is to develop or extend theory in the case of a collective crisis, the goal of our sampling methodology was to select those cases which are likely to fill theoretical categories (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Glaser and Strauss 1967; Meyer 2001). “Theoretical sampling is done in order to discover categories and their properties, and to suggest the interrelationships into a theory” (Glaser and Strauss 1967, p. 73). Using this approach “cases are selected because they are particularly suitable for illuminating and extending relationships and logic among constructs” (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007, p. 27). Therefore, rather than focusing on a representative sample, this qualitative sampling approach seeks a richness of information and so cases are chosen purposefully rather than randomly (Meyer 2001).

Companies associated with the Rana Plaza accident were initially identified from a report by the Clean Clothes Campaign and the International Labor Rights Forum (Foxvog et al. 2013). An initial screening was carried out where we considered the initial reaction by each company to the crisis and the availability of data related to the crisis for each company. Companies were selected to ensure that all categories or types of company reaction to the crisis were included in the sample. In terms of data availability, we verified whether there were company press releases, communications posted on the company website, corporate social responsibility reports, and company Twitter accounts and whether data were available in English. For each category of company reaction, we choose those cases where there was greatest information availability thus providing transparency on the process we wish to observe (Pettigrew 1990; Eisenhardt 1989). The eight companies chosen for the study are Auchan, Benetton, Carrefour, El Corte Inglés, JC Penney Loblaw, Mango, and Primark.

Data Collection

A wide variety of data sources were used in the study. Diverse data sources allowed us to review the crisis from different perspectives and also to finally triangulate our findings (Pettigrew 1990). We used data from company press releases, company websites, company Twitter accounts, newspaper articles, reports by NGO’s as well as the websites of various organizations involved in helping victims or putting processes in place in the aftermath of the Rana Plaza crisis. Reports and press releases were collected directly from company websites. Twitter messages to and from company Twitter accounts were also collected. An initial search was conducted using the site’s advanced search option and a list of keywords. Searching using hashtags was rejected at this stage as it resulted in less articles being found, perhaps due to their non-persistent nature (Romero et al. 2011). Once the Tweets had been found, they were read to ensure that they were related to the incident.

News articles linking each of the companies with the Rana Plaza crisis were collected from the Dow Jones Factiva database using a keyword search. Sources selected included fifty-six newspapers covering nineteen different countries. News sources were restricted to those in the English language. Only national-level newspapers with the highest circulation rates were included. Newspapers which focus on national rather than regional or local news were preferred as these are more likely to reflect the national agenda (Barkemeyer et al. 2009).

Information from the website of the Clean Clothes Campaign (NGO) as well as the websites of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh and the Rana Plaza Arrangement was gathered. This included information reported directly on the site as well as downloadable reports. In tandem with this, and to get a clear overview of the crisis history of each company, an intensive internet search was also conducted. This focused in particular on whether there had been prior involvement particularly in labor or human rights scandals (Coombs and Holladay 2006).

The various data sources were used in our data analysis and contributed to our findings as we now describe.

Information from the company including reports and press releases and information from Twitter accounts were used to understand the position adopted by the company post-crisis as well as longer term corrective actions implemented. Information from the company was also used in the construction of the timeline of events as presented in Appendix 1.

Our analysis of newspaper articles had two functions. In the first case, it allowed us to determine the companies which were most visible in the media and, using sentiment analysis, whether this news coverage was positive or negative. Secondly, qualitative analysis and coding of each media article allowed understanding of how the crisis was framed by the media and what the most salient aspects of the crisis as communicated to the public were. This facilitated understanding the reputational threat to individual companies based on media visibility and media framing.

Third-party websites such as the Clean Clothes Campaign, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, and the Rana Plaza Arrangement gave important objective information about the crisis. They helped identify the companies involved and their crisis histories. These sources also give an unbiased view on company post-crisis strategies as well as being an important information source for the construction of the timeline in Appendix 1. All of these sources used together facilitated a deep understanding of the crisis from the media, company, and third-party perspectives.

Data Analysis

The data analysis method employed follows that described by Eisenhardt (1989). Each of the cases was firstly studied individually in detail and then the cases were compared to discover emergent themes and give new insights. Following inductive methods, company press releases, corporate websites, company tweets, and corporate social responsibility reports for the years 2013 and 2014 were read and analyzed by the authors in order to gain an understanding of the position adopted by the company post-crisis.

A file was created for each company where all of the information collected about that company (company press releases, information from corporate websites, company tweets, corporate social responsibility reports, and reports by NGOs where the company was mentioned) was amalgamated. Each company file of information was then read by both researchers to become familiar with each individual company case. A spreadsheet for each case was then compiled which outlined the timeline of actions by each company (as reported either by the company itself or by a third party). Each individual case was then discussed by both researchers. This process facilitated cross comparison of cases in terms of similarities and differences. This collaborative process also facilitated categorization of cases (as per Table 2).

Newspaper articles which were returned from the Factiva search were analyzed. The valence of print media articles in terms of positive or negative orientation was measured. The computer-based program, General Inquirer (GI), was used to carry out the sentiment analysis. This has been used for a similar purpose in previous research (Comyns 2014). GI uses the Lasswell and the Harvard IV dictionaries to analyze the sentiment in text. Preloaded dictionaries include 1915 words of a positive outlook and 2291 words of a negative outlook (General Inquirer 2002). GI considers only the individual words which appear in the text and does not consider the context or any relationship between words (Evans 2002). Each of the articles was analyzed individually. Each article was classified as either positive (positive words > negative words), negative (negative words > positive words), or neutral (positive words = negative words).

Each of the newspaper articles was then individually read and coded. We found several cases where, due to print syndication, the same articles appeared in different newspapers. With duplicate articles removed, the sample consisted of 404 articles. Using open coding, data were considered in terms of the events, actions, and interactions (Corbin and Strauss 1990) and to determine code categories (Pellegrino and Lodhia 2012). An initial sample of fifty articles was used to generate the code categories and the framework. These articles were carefully chosen from the overall sample. This process was to ensure a representative sample of articles from various newspapers from different countries and published at different time periods. The coding framework was established and agreed by both authors. Coding was carried out by one author with frequent consultation on the codes as well as emergent themes with the second author (Green and Li 2011). Emergent themes were also considered in terms of theoretical meaning (Pellegrino and Lodhia 2012). It was found that the same codes and themes reoccurred and so saturation was reached where no new codes emerged (Pellegrino and Lodhia 2012). Samples of coded articles were then checked by the second researcher to ensure reliability and consistency in the coding process (Hrasky 2011).

Third-party websites (for example Rana Plaza Arrangement 2014 and Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh 2014) and reports by NGOs, in particular by the Clean Clothes Campaign, were also downloaded and read. The results from all of our data analysis were then linked back to the literature in an iterative process.

Findings

The findings from our study are presented in this section. Firstly, a timeline of events following the Rana Plaza collapse is presented. The timeline includes the trend of newspaper coverage, the timing of important events, company actions, and a selection of company communications. Secondly, the crisis history for each company is outlined. Thirdly, we review the company response following the accident. We classify responses as short term or long term and also in terms of whether they are accommodative or defensive. Finally, the results of the newspaper analysis are presented. This includes media visibility in terms of the number and valence of newspaper articles as well as the results of the qualitative analysis of articles.

Rana Plaza Event Timeline

In order to display the events which took place following the accident at Rana Plaza, we present an event timeline in Appendix 1. This timeline gives a high-level view of the important events, newspaper coverage, company actions, and communications in the twelve months following the accident. Central to the figure is the trend showing the number of newspaper articles linking one or several of our eight focal companies with the Rana Plaza accident in each month between April 2013 and April 2014. Where the same article was returned multiple times during our search on Factiva, for example if an article mentioned Primark and Mango and Benetton, duplicates were removed so that each article was counted only once. The trend thus shows the number of original articles found.

Significant events in the year following the disaster are also marked on this timeline as follows:

-

May 9: Fire at Tung Hai sweater factory in Bangladesh.

-

May 15: Deadline for retailers to sign up to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety (the Accord). The Accord is an independent agreement between retailers and trade unions, is legally binding, and requires that garment factories meet minimum safety requirements. Over one hundred and ninety brands (mostly European) have signed up to the Accord.

-

July 10: The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (the Alliance) was formed on July 10, 2013. The Alliance is formed of mainly American retailers, working with various stakeholders towards improving workplace safety in the Bangladesh garment industry. Unlike the Accord, the Alliance is not legally binding (The Economist 2013).

-

October 8: Fire at the Aswad Composite Mills factory in Bangladesh.

-

November 24: 1-year anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire, one hundred and twelve garment workers were killed just six months before the Rana Plaza building collapse.

-

January 2014: Launch of the Rana Plaza Donors Trust fund. This fund, financed by retailers, government, and individual donors, is aimed at collecting funds to pay compensation to victims and their families.

-

April 24, 2014: 1-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza accident.

Above this information in Fig. 2 in Appendix 1, we outline the dates each month when companies communicated via press releases or in some cases social media (by Twitter). In the lower section of the Figure, we have added company actions around the timeline. Most of our focal companies signed the Bangladesh Accord on or before the May 15 deadline. Auchan signed the Accord at a later date. JC Penney opted instead to sign up to the Alliance. The figure presents a selection of the main important communications made by each company in the time period. Where a company communicated a message using several forms of media, i.e., press release and Twitter, only one form is recorded here. Minor updates by companies have been omitted. The key accompanying this figure outlines the content of these communications. For example, immediately after the crisis on April 24, Loblaw tweeted its condolences (labeled Loblaw (1)) and then on April 25 issued a press release stating that it used a supplier located in the collapsed building (labeled Loblaw (2)).

Crisis History

The crisis history for each of the eight companies prior to and including 2013 yielded results as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that four of the eight companies that we consider in our study had previously been linked with garment factory accidents in Bangladesh. Carrefour was linked with three previous accidents in 2005, 2010 as well as the 2012 Tazreen Fashions fire. El Corte Inglés and Auchan were also associated with the Tazreen Fashions fire. There was one previous incident found associated with Auchan, while El Corte Inglés was also associated with a 2010 garment factory fire in Bangladesh as well as with an earlier labor issue in Turkey. JC Penney was being supplied by a Bangladeshi factory where there was a fire in 2010.

Benetton has an ongoing scandal linked with indigenous people in Argentina. This issue appeared to be at its most harmful in terms of reputation between the years 2004 and 2007 (The Argentina Independent 2014). Loblaw and Mango were not found to have previous human rights or labor-related issues. Primark was found to have been linked to sweatshops in the UK in 2008. No link was found between Primark, Benetton, Loblaw, and Mango and accidents at garment factories in Bangladesh, prior to Rana Plaza.

Prior to Rana Plaza, Carrefour and El Corte Inglés were the most exposed in terms of reputation and had a history of several prior similar incidents in Bangladesh. Auchan and JC Penney also had a prior history of accidents in Bangladesh, although with fewer cases. Primark, Loblaw, Mango, and Benetton had the best pre-crisis reputations with notably no prior history of similar incidents in Bangladesh.

Company Reaction to Rana Plaza

In the aftermath of the Rana Plaza building collapse, we analyzed the responses of the eight companies. We focused both on the response that companies adopted immediately after the crisis as well as longer term responses. We identify distinct response strategies among the eight companies.

Short-Term Strategies

Immediately following the disaster, Primark and Loblaw acknowledged that they sourced clothing from garment factories operating in Rana Plaza. On April 25, 2013 Loblaw issued a statement on its company website acknowledging that the complex “included a factory that produced a small number of Joe Fresh apparel items for Loblaws Inc”(Loblaw 2013a). In a tweet from @joefresh on April 26, 2013 Loblaw also expressed sorrow and sympathy for the victims. Similarly, Primark issued a press release on the April 26, 2013 which included the following “Primark confirms that one of its suppliers occupied the second floor of the eight storey building” and in the same statement Primark expressed its sorrow and condolences for the victims “The company is shocked and deeply saddened by this appalling incident at Savar, near Dhaka, and expresses its condolences to all of those involved”(Primark 2013). The positions adopted by both Primark and Loblaw are in line with the notion of mortification “in which those accused of wrongdoing admit guilt and express regret” (Benoit 1995, p. 92) and also of penitential accounts which “acknowledges that harm was done, that they were responsible, and tries to atone” (Sims 2009, p. 464). The strategy adopted by Primark and Loblaw is therefore accommodative.

Auchan and Carrefour both initially denied that they had sourced clothing from factories in Rana Plaza. On May 15, 2013, Auchan issued a press release denying involvement and on May 23 issued a statement on its website stating “We forcefully restate that we have not placed orders with any Rana Plaza workshops” (Auchan 2013a). Carrefour issued a press release on May 14, 2013 where they stated that “Carrefour can confirm that it had no business dealings with any of the local companies which were operating in the building which collapsed”(Carrefour 2013a) even though evidence of clothing labels for Carrefour was found in the rubble of the building (Foxvog et al. 2013). Auchan eventually acknowledged that unauthorized subcontracting to suppliers located in Rana Plaza was possible (Foxvog et al. 2013). The strategy adopted by Carrefour and Auchan is in line with the strategy of denial as described by both Benoit (1995) and Sims (2009). Although Auchan later acknowledged that there may have been a connection to Rana Plaza, the company stated that the supplier was unauthorized. This is akin to reactive decoupling as described by Sims (2009) which involves “separating the organization from the individuals or units that committed the wrongful act” (Sims 2009, p. 464). These strategies by Carrefour and Auchan are highly defensive as they do not accept any responsibility for the crisis.

Mango, Benetton, and El Corte Inglés acknowledged that they sourced garments from factories located in Rana Plaza. On April 27, 2013, Mango tweeted a link to a statement on the company Facebook page expressing its sorrow at the event and acknowledging its involvement (Mango 2013). In a similar vein, Benetton posted a statement on Twitter on April 30, 2013 stating that “We have since established that one of our suppliers had occasionally subcontracted orders to one of these Dhaka-based manufacturers” (Benetton 2013). Even in a statement one year after the event, the company continued to reaffirm its position stating that “Benetton Group has never had any kind of continuous relationship with the suppliers that operated in the Rana Plaza building. New Wave Style, a local supplier, only received occasional orders, amounting to 0.06 % of our production” (Benetton 2014b). On April 26, 2013, El Corte Inglés issued a press communication on its website expressing its sorrow that the disaster had occurred and acknowledging that the company had a commercial link with one of the garment factories (El Corte Inglés 2013b). In this statement, the company also emphasized that the local authorities were responsible for ensuring the safety of the infrastructure of industrial buildings. All three companies tried to provide justification and to minimize their involvement. Mango emphasized that although production was planned it had not taken place (Mango 2013). Benetton stressed that the garments manufactured at Rana Plaza constituted only a very insignificant percentage of their entire production and El Corte Inglés places the responsibility for building safety with local authorities in Bangladesh. This strategy is akin to ideological accounts where organizations “attempt to mitigate the effects of the organizations unethical action” or to “justify the predicament” (Sims 2009, p. 464). This type of strategy could also be described as minimization (Benoit 1995) or trying to downplay the gravity of the situation to reduce negative feeling towards the company. The companies in this case neither fully accept nor deny responsibility.

According to a report by the Clean Clothes Campaign (2013), labels from JC Penney were found in the rubble of the collapsed building but the company initially neither denied nor acknowledged its link to Rana Plaza (Foxvog et al. 2013). We did not find any press releases about the Rana Plaza incident from JC Penney and there was no specific information posted about Rana Plaza on the company website. From an examination of the company Twitter account, we found twelve tweets related to the incident. These tweets were responses to messages tweeted at the company and explained that the company was “part of a broad alliance to develop industry-wide solutions for improving factory safety in Bangladesh” without referring directly to Rana Plaza. JC Penney appears to be following a strategy of non-communication or corporate silence as described by Heugens et al. (2004). The company appears to employ an avoidance tactic by not adopting a position or engaging in any direct communication in the aftermath of the crisis. We place this towards the defensive end of the strategy continuum as although they neither confirm nor deny involvement, a lack of communication would denote that the company wishes to distance itself from taking any responsibility.

Long-Term Strategies

We now consider the long-term strategies employed by the eight companies following Rana Plaza. Long-term responses were classified under the headings as described by Sims (2009). “Fixing the outcome” includes financial compensation, donations, and relief efforts in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. “Implement new policies” includes policies implemented following the disaster while “employee training” includes training programs on ethical issues for employees or suppliers. In addition to the categories described by Sims (2009) we have added three further categories of actions found to be relevant in this context. The category “prevention of further harm” includes actions such as building inspections and audits, which companies take to ensure that a similar accident cannot occur elsewhere. “Creation of new positions” involves the creation of positions to increase company presence in Bangladesh. This is particularly relevant where a disaster occurs far from the home country. The final category is “participation in collective agreements.” We categorize collective agreements as multi-stakeholder policies designed to prevent future accidents. These include signing up to the Accord or the Alliance. This is an example of a collective reputation management strategy. Collective strategies are used by companies in the same industry sector to restore industry-wide or collective reputation in the aftermath of a serious crisis. It is somewhat akin to Responsible Care, a self-regulatory program, launched by the chemical industry in the aftermath of the Bhopal accident (Barnett and Hoffman 2008; Barnett 2007b). We find that all companies participated in collective agreements by either signing the Accord or the Alliance. Primark focuses on actions associated with “fixing the outcome” by providing compensation as well as relief in the immediate aftermath of the incident. Similarly, Loblaw donated financially but also implemented new policies and created new positions to increase company presence in Bangladesh. Primark and Loblaw also carried out audits of other suppliers to ensure that a similar incident could not reoccur. From the information available, Primark gave the greatest amount of financial compensation to victims. Carrefour continued to deny its involvement in Rana Plaza and the only action by the company was to sign the Accord. Although Auchan initially also denied involvement, they did contribute financially as well as undertaking many further actions. Similar long-term actions were taken by Benetton, Mango, and El Corte Inglés in that they all signed the Accord and took some actions to fix the problem. Benetton offered some local relief, although has not contributed to the Rana Plaza Donors Trust Fund. Mango and El Corte Inglés have donated to the fund but the amount was not disclosed. JC Penney, who avoided the issue, did not donate financially to the compensation fund but did implement new policies and did join the Alliance. In Table 2, we have summarized the short- and long-term responses by the companies under consideration. We have grouped companies with similar short-term responses together and shown these strategies on the accommodative to defensive continuum.

Newspaper Analysis

Media Visibility

Table 3 outlines the results of the newspaper coverage of Rana Plaza for the eight individual companies. Where the same article mentions several companies, the article is counted once for each company, this means that the same article can be counted multiple times since it will have a visibility effect for each of the companies mentioned. It is apparent that of the eight companies, Primark has been most visible in the media spotlight. Primark had almost twice the number of media articles compared to Loblaw and almost three times that of Benetton and Mango. Auchan and JC Penney had the least amount of media visibility. It is also interesting to consider the geographical spread of articles concerning Primark. Primark is headquartered in Dublin and the UK, and so received a lot of coverage in the UK and Ireland. However, Primark was mentioned in articles in geographies including the USA and Canada, China, India, Australia, and New Zealand, countries where it did not have retail outlets at that time. In contrast, Loblaw which is headquartered in Canada was highlighted mainly by Canadian and US newspapers in relation to the incident, with a small amount of coverage in the UK and very little further afield. In terms of the valence of the newspaper articles, Primark also had the highest number of negative newspaper articles followed by Loblaw, Mango and Benetton. From the literature, we know that companies with the highest levels of media attention are most likely to be those with the greatest threat to company reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990).

Qualitative Analysis of Newspaper Articles

The results of the qualitative analysis of newspaper articles show how the accident at Rana Plaza was conveyed to the public by the media. A number of main and recurring themes were found as a result of our coding process. These themes are considered in the context of media frames as discussed in the literature. The main themes which emerged are outlined below.

Human Interest

Under the heading of ‘human interest,’ one of the most frequently occurring themes was ‘severity of the crisis’. In 93 % of the articles in our sample, the scale of the disaster in terms of the number of victims or relative size was highlighted. For example, an article in the Scotsman on May 14, 2013 described the accident as ‘the worst industrial loss of life since the 1984 Bhopal disaster in India.’ A second theme under the heading of human interest was that of the ‘individual case.’ This code was relevant in 22 % of the articles examined. Here articles included an account of the accident naming specific individuals. For example, the Toronto Star in an article dated April 29, 2013 describes how an individual was rescued from the rubble as well as the injuries suffered: “Garment worker Pakhi Khatun, 30, was rescued from the rubble 36 h after the collapse, Pakhi, who is being treated in Savar at Enam Medical College, had to have both of her legs amputated in order to rescue her.” Human interest accounts also include direct quotations from victims, relatives of victims, and rescue workers. The ‘human interest’ frame makes the story more compelling for the reader and can also illicit a higher emotional response (Valkenburg et al. 1999).

Responsibility for the Accident

Another major theme which emerged was attribution of responsibility. We found that in 25 % of articles responsibility for the accident was attributed at the level of a specific individual, be that the owner of the building or the factory owners. In an article in The Guardian on June 7, 2013, one of the victims puts the blame firmly on the owner of the building as follows: “Rana is to blame. He knew there were problems, but sent us back in there.” Only in 6.7 % of articles, responsibility for directly causing the accident was assigned to retailers or brands which were being supplied by the factories in Rana Plaza. In these cases, retailers were identified as a group, with no individual brands being named. In an article in the Sydney Morning Herald on the April 27, 2013, the president of the National Garment Workers’ Federation of Bangladesh is quoted as saying “Western companies are directly responsible for the deaths of the workers.” Instances of individual companies being named as being responsible for the accident occur less frequently (5.9 % of articles). In some cases, this involves quotations from the companies themselves taking on responsibility. For example, Primark is quoted in an article in the New York Times on May 1, 2013 as stating “we are fully aware of our responsibility”. Somewhat surprisingly, the government of Bangladesh, responsible for enforcing legislation and building regulations, was apportioned blame for the accident in only 4.2 % of our articles.

Solution Following the Accident

In addition to the responsibility for the accident, the media also covered the issue of the solution, both in terms of an immediate solution and longer term solutions to prevent such accidents from reoccurring in Bangladesh. Conversely to how responsibility for the accident was assigned (specific individuals), the solutions which are offered are at the level of the organization (retailers). The results show that in almost 77 % of articles, retailers (as a group) are identified as being the source of a solution to the issue. This compares with 26 % of articles which have identified the government as the solution (either the government of Bangladesh or elsewhere) and 10 % identifying that the solution should come from society in general. Interestingly, only in less than 4 % of articles are individual factory owners identified as being responsible for providing the solution. This means that while retailers are not being explicitly ‘blamed’ for causing the crisis, at some level they are being attributed responsibility for the crisis, since providing the solution is also an attribution of responsibility. (Semetko and Valkenburg 2000, p. 96).

The most frequently discussed post-crisis solutions were compensation of the victims and their families (41 % of articles), signing the Accord (38.9 % of articles), improving safety standards (25 % of articles), signing the Alliance (12 % of articles) as well as factory inspections (9.9 % of articles). Boycotting retailers was discussed in about 6 % of articles, but the news media did not portray this as effective since it might jeopardize the jobs of those (mostly female and poor) who are employed in the garment industry.

Prior Accidents in the Garment Industry in Bangladesh

We found that the media frequently referred to past accidents in the garment industry in Bangladesh. Our findings show that 21.8 % of articles make a general reference to previous accidents, without mentioning specific occurrences, while 18 % of articles specifically mention the fire at Tazreen Fashions in November 2012. Other specific incidents were also mentioned in a smaller number of articles. The history of the garment industry and past incidents and accidents were used to highlight the ongoing safety issues in the industry.

Economic Consequences

An important recurring theme which was strongly reiterated in the media was the economic importance of the garment industry to Bangladesh. This was covered in 28 % of articles. For example, an article in the Financial Times on April 25 includes the following: “Bangladesh is the world’s second-biggest garment export industry, after China.” In another article in the same newspaper on May 2, reference is made to the fact that the garment sector makes up 13 % of the gross domestic product of Bangladesh. This serves to highlight and re-enforce to the reader the importance of the garment industry to the development of Bangladesh. This is in line with the ‘economic’ media frame (An and Gower 2009).

An overview of the results from the newspaper analysis is presented in Table 4. This shows the percentage of codes for each theme as well as the percentage of articles where the code was present.

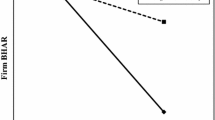

Theoretical Insights: Proposition Development

Based on our results, we now present the theoretical insights from the study. We have summarized our findings and the relationships on which we base our propositions in the model shown in Fig. 1. In the case of the collective crisis, we firstly consider crisis history as an antecedent of crisis response strategy. We then examine the relationship between the crisis response strategy and post-crisis reputation, the latter being the dependent variable. We argue that the relationship between the crisis response strategy and post-crisis reputation relationship is moderated by the crisis setting (collective or individual). We now describe each of our propositions in detail.

Crisis History and Crisis Response Strategy

Crisis history and prior reputation have been identified in the literature as important antecedents when determining how a company may react to a crisis and the strategy that will be adopted (Bundy and Pfarrer 2015). As discussed in the Findings section, and outlined in Table 1, prior to Rana Plaza, Carrefour and El Corte Inglés had poor crisis histories, especially in Bangladesh. Auchan and to a lesser extent JC Penney may also have been in vulnerable positions, being associated with previous accidents in Bangladesh. Primark, Loblaw, Mango, and Benetton had relatively good crisis histories and were not found to be involved with any other accidents in the garment industry in Bangladesh.

When we consider the company post-crisis strategy, in Table 2, in tandem with this information the following picture emerges. Primark and Loblaw, both with good crisis histories, adopt accommodative strategies, accepting responsibility for the crisis. Mango and Benetton, also with good crisis histories, try to minimize and justify their involvement but accept that they were being supplied by factories in the building. Carrefour and Auchan, both with poor crisis histories, adopt defensive strategies, denying any involvement. Meanwhile, El Corte inglés, also with a poor crisis history, tries to minimize the damage by shifting the blame to the authorities in Bangladesh. JC Penney, with a record of being involved in a similar crisis, remains silent on the issue, not adopting a position either way.

This presents quite an interesting situation. While the SCCT literature would suggest that companies with poorer crisis histories need to adopt more accommodative strategies to limit reputational damage (Coombs and Holladay 2006; Coombs 2007a), we do not find this to be the case. We find that those companies with poor crisis histories either try to deny involvement, thus adopting a purely defensive strategy, try to shift the blame to other parties, or remain unresponsive. This is in line with the prediction of Bundy and Pfarrer (2015) that companies with lower social approval (worse reputation) pre-crisis will adopt more defensive post-crisis strategies, so refusing to accept responsibility. In this case, companies try to distance themselves from the crisis to avoid any further reputational damage. In a collective setting, this may be possible due to the presence of a large number of companies. It will be difficult for stakeholders to consider crisis history for all companies involved, so this factor may get crowded out. Those with poor crisis histories can ‘get lost in the crowd.’

For companies with good crisis histories we see different reactions. Those companies with no record of previous similar crises, notably Primark and Loblaw, adopt accommodative strategies. Contrary to those with poor crisis histories, those with good crisis histories appear to be more likely to step forward and take responsibility. In line with Rhee and Haunschild (2006), this can be explained by a desire to protect their good reputation and meet stakeholder expectations. Meanwhile, Mango and Benetton, also with good crisis histories, adopt less accommodative strategies. Rather than accepting responsibility, they neither really accept nor deny responsibility but rather try to justify or minimize their association with the crisis. This reaction is more in line with what Bundy and Pfarrer (2015) predicted that companies with higher levels of social approval would adopt more defensive strategies post-crisis. This strategy can be explained by these companies attempting to minimize negative reputational effects.

We also note that the time taken to communicate may also be related to the strategy adopted. From our timeline in Appendix 1, Primark and Loblaw both responded in the period immediately following the crisis, Loblaw on April 24 and Primark on April 26. In the case of these two companies, they immediately accepted responsibility. While Benetton also responded quickly on April 24, this communication was to distance themselves from the crisis, the company only confirming their association via a Tweet on April 29. Mango responded to the crisis on April 27. Those companies which adopted very defensive strategies took notably longer to communicate in the aftermath of the crisis. Carrefour first communicated on May 14 and Auchan on May 15, which is three weeks after the accident. JC Penney failed to communicate at all. This delay may be due to waiting to observe the behavior of others or to determine whether stakeholders/media had identified their involvement. A reluctance to communicate could be further evidence of the attempt by companies who adopt strong defensive strategies to distance themselves from the crisis. This leads us to our first proposition:

Proposition 1

-

(a)

In a collective crisis, companies with a poor crisis history are more likely to adopt defensive crisis response strategies.

-

(b)

In a collective crisis, companies which adopt defensive crisis response strategies will communicate much later compared to companies which adopt more accommodative strategies.

Crisis Response Strategy and Post-Crisis Reputation

The short-term strategy adopted by a company post-crisis can influence the reputation of the company and how stakeholders form judgements about the company in the immediate aftermath (Bundy and Pfarrer 2015; Coombs 2007a). We have seen previously that it is generally agreed that accommodative strategies minimize the risk to company reputation. As presented in Table 2 and discussed above, Primark and Loblaw adopted accommodative strategies post-crisis, while at the other end of the continuum Carrefour, Auchan and JC Penney adopted defensive strategies. We now consider how the post-crisis strategy may have impacted organizational reputation.

From our analysis of media visibility, we note that each of the companies in the sample had different levels of media visibility. Primark and Loblaw attracted most media attention and also the most negative media coverage. Media visibility, especially that which is negative, adversely affects reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Brammer and Millington 2006). Those companies which are reported on in the media will be those which the public are most likely to link to the crisis, taking into account media agenda setting effects (Carroll 2004). From the qualitative analysis of media articles, it is apparent that the media frequently associated companies with the activities in the building at the time of the collapse. This was done either by associating specific brands with one of the garment factories or by referring to the fact that labels for specific brands were found in the rubble of the building. Although visibility did not mean attributing responsibility for the accident, the direct link between the companies and the victims who were sewing clothes when the accident happened would have served to shape public opinion. Given that the human interest frame was one of the most frequently occurring, the connection between specific companies and the victims is likely to have generated negative emotions (Cho and Gower 2006). Given media agenda setting as well as the power of media frames to influence public perception, the most visible companies are those likely to suffer the greatest negative reputational consequences.

We now further consider the question of media visibility. Why is it that Primark and Loblaw were so visible in the media, bearing in mind that Benetton and Mango are very well-known international brands and JC Penney is well known in the US? If we consider the timeline of events as presented in the Figure in Appendix 1, we see that both Primark and Loblaw acknowledged their involvement and expressed their condolences in the days immediately following the crisis. At the same time, Benetton and Mango were distancing themselves from the accident stating that they were not being supplied by garment factories in the building, while JC Penney remained silent. When we consider the company’s short-term reaction to the crisis and the level of media visibility, we propose that there may be a connection. By adopting an accommodative strategy, Primark and Loblaw accept the burden of responsibility for the crisis, and effectively put themselves in the story. Newspapers are probably more likely to include the names of companies who have confirmed involvement with the accident.

From Table 2, it is also apparent that Primark and Loblaw both paid most in financial compensation to the victims post-crisis. The literature on corporate reputation posits that provision of financial compensation and philanthropic donations are effective in terms of reputation building (Brammer and Millington 2006; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Since Primark and Loblaw pay the most post-crisis, this indicates that these companies also had more to do to rebuild reputation. The financial price paid by these companies post-crisis gives further support to our argument above that Primark and Loblaw suffered most in terms of negative reputation by accepting the burden of responsibility. In line with extant literature, we clearly see that accommodative strategies are the most costly option (Coombs 2007b).

By adopting an accommodative strategy, Primark and Loblaw effectively shoulder the burden of responsibility, incur more reputational damage, and ultimately pay more financially post-crisis. Companies who adopt a more defensive strategy appear to suffer less at least in the short term as they are less visible in the media and also pay less monetary compensation. This leads to our second proposition:

Proposition 2

In a collective crisis, the burden of responsibility will not be equally shared among organizations. Those companies who adopt accommodative strategies accept the burden of responsibility and the burden of negative reputation.

Crisis Setting as a Moderator of the Crisis Response Strategy and Post-Crisis Reputation Relationship

The organizational response to a crisis influences stakeholder judgement of the company since it can generate feelings of anger and lead to negative word of mouth or to the stakeholder ending its relationship with the company (Coombs and Holladay 2009). These factors may also negatively affect reputation. The crisis management literature has focussed some attention on the ‘best’ crisis response strategies in terms of minimizing these negative effects. It is generally accepted that accommodative strategies be that apology, expressing remorse/sympathy/regret, or offering compensation are most effective at limiting reputational damage (Coombs and Holladay 2009; Benoit and Drew 1997; Benoit 1995; Coombs and Holladay 2008; McDonald et al. 2010; Claeys et al. 2010). These are argued to be effective strategies given that they focus on the needs of victims. Where compensation is also offered, some of the harm caused can be offset. These strategies all have a positive effect on stakeholder perception of the organization (Coombs and Holladay 2008; McDonald et al. 2010). Defensive strategies including denial, justification, or offering excuses attracts more negative reaction from stakeholders (McDonald et al. 2010).

In a collective crisis, we find that an accommodative strategy has a different effect compared to in an individual crisis. In a collective crisis, companies that adopt an accommodative strategy stand out from the crowd by associating themselves directly with the incident. Conversely, those who adopt a defensive strategy take advantage of the group setting and ‘get lost in the crowd.’ In a collective crisis, it may not always be clear which organizations are involved or which are to blame so stakeholders rely heavily on the media for this information. The media in turn focus on those companies which accept responsibility and highlight them as being associated with the crisis, while those which deny their association are less visible.

We find evidence that companies who adopt accommodative strategies accept the burden of responsibility for the crisis, incur the highest levels of media attention and so reputational damage, and also pay most in terms of monetary contributions post-crisis. Those who adopt defensive strategies suffer less reputational damage and pay less in monetary compensation. We argue that the relationship between the crisis strategy and post-crisis reputation is moderated by the crisis setting. This leads to our third proposition.

Proposition 3

The relationship between the crisis response strategy and post-crisis reputation is moderated by the crisis setting.

Discussion