Abstract

Purpose

Patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (BC) or ductal carcinoma in situ are increasingly choosing to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) to reduce their risk of contralateral BC (CBC). This is a particularly disturbing trend as a large proportion of these CPMs are believed to be medically unnecessary. Many BC patients tend to substantially overestimate their CBC risk. Thus, there is a pressing need to educate patients effectively on their CBC risk. We develop a CBC risk prediction model to aid physicians in this task.

Methods

We used data from two sources: Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results to build the model. The model building steps are similar to those used in developing the BC risk assessment tool (popularly known as Gail model) for counseling women on their BC risk. Our model, named CBCRisk, is exclusively designed for counseling women diagnosed with unilateral BC on the risk of developing CBC.

Results

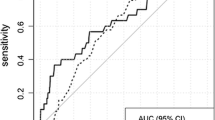

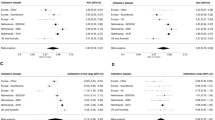

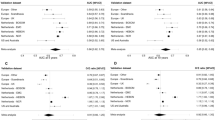

We identified eight factors to be significantly associated with CBC—age at first BC diagnosis, anti-estrogen therapy, family history of BC, high-risk pre-neoplasia status, estrogen receptor status, breast density, type of first BC, and age at first birth. Combining the relative risk estimates with the relevant hazard rates, CBCRisk projects absolute risk of developing CBC over a given period.

Conclusions

By providing individualized CBC risk estimates, CBCRisk may help in counseling of BC patients. In turn, this may potentially help alleviate the rate of medically unnecessary CPMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH et al (2007) Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol 25:5203–5209

Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB et al (2009) Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol 27:1362–1367

King TA, Sakr R, Patil S et al (2011) Clinical management factors contribute to the decision for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. J Clin Oncol 29:2158–2164

Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP (2010) Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Ann Surg Oncol 17:2554–2562

Katipamula R, Degnim AC, Hoskin T et al (2009) Trends in mastectomy rates at the Mayo Clinic Rochester: effect of surgical year and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol 27:4082–4088

Wong SM, Freedman RA, Sagara Y et al (2016) Growing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy despite no improvement in long-term survival for invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001698

Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV et al (2011) Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol 29:1564–1569

Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Trialists’ Group (2008) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 9:45–53

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2005) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365:1687–1717

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M et al (2010) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 11:1135–1141

Uyeno L, Behrendt, Vito C (2012) Contralateral breast cancer: impact on survival after unilateral breast cancer is stage-dependent. In: ASCO breast cancer symposium abstract 69

Bertelsen L, Bernstein L, Olsen JH et al (2008) Effect of systemic adjuvant treatment on risk for contralateral breast cancer in the Women’s Environment, Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:32–40

Kurian AW, McClure LA, John EM et al (2009) Second primary breast cancer occurrence according to hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:1058–1065

Brewster AM, Parker PA (2011) Current knowledge on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among women with sporadic breast cancer. Oncologist 16:935–941

Bouchardy C, Benhamou S, Fioretta G et al (2011) Risk of second breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status and family history. Breast Cancer Res Treat 127:233–241

Khan SA (2011) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: What do we know and what do our patients know? J Clin Oncol 29:2132–2135

Murphy JA, Milner TD, O’Donoghue JM (2013) Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in sporadic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 14:e262–e269

Chen Y, Thompson W, Semenciw R, Mao Y (1999) Epidemiology of contralateral breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 8:855–861

Graeser MK, Engel C, Rhiem K et al (2009) Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 27:5887–5892

Cook LS, White E, Schwartz SM et al (1996) A population-based study of contralateral breast cancer following a first primary breast cancer (Washington, United States). Cancer Causes Control 7:382–390

Haffty BG, Harrold E, Khan AJ et al (2002) Outcome of conservatively managed early-onset breast cancer by BRCA1/2 status. Lancet 359:1471–1477

Rhiem K, Engel C, Graeser M et al (2012) The risk of contralateral breast cancer in patients from BRCA1/2 negative high risk families as compared to patients from BRCA1 or BRCA2 positive families: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res 14:R156

Reiner AS, John EM, Brooks JD et al (2013) Risk of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer in noncarriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with a family history of breast cancer: a report from the Women’s Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. J Clin Oncol 31:433–439

Hislop TG, Elwood JM, Coldman AJ et al (1984) Second primary cancers of the breast: incidence and risk factors. Br J Cancer 49:79–85

Schaapveld M, Visser O, Louwman WJ et al (2008) The impact of adjuvant therapy on contralateral breast cancer risk and the prognostic significance of contralateral breast cancer: a population based study in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Res Treat 110:189–197

Saltzman BS, Malone KE, McDougall JA et al (2012) Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2-neu expression in first primary breast cancers and risk of second primary contralateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 135:849–855

Cook LS, Weiss NS, Schwartz SM et al (1995) Population-based study of tamoxifen therapy and subsequent ovarian, endometrial, and breast cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 87:1359–1364

Herrinton LJ, Barlow WE, Yu O et al (2005) Efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer: a cancer research network project. J Clin Oncol 23:4275–4286

Abbott A, Rueth N, Pappas-Varco S et al (2011) Perceptions of contralateral breast cancer: an overestimation of risk. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3129–3136

Metcalfe KA, Narod SA (2002) Breast cancer risk perception among women who have undergone prophylactic bilateral mastectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:1564–1569

Lostumbo L, Carbine N, Wallace J, Ezzo J (2004) Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD002748

Lostumbo L, Carbine NE, Wallace J (2010) Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11):CD002748

Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Degnim AC et al (2010) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is associated with a survival advantage in high-risk women with a personal history of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 17:2702–2709

Carson W, Otteson R, Hughes MA et al (2013) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer: a review of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) database. In: Society of Surgical Oncology 66th annual cancer symposium abstract 13

Frost MH, Schaid DJ, Sellers TA et al (2000) Long-term satisfaction and psychological and social function following bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. JAMA 284:319–324

van Geel AN (2003) Prophylactic mastectomy: the Rotterdam experience. Breast 12:357–361

Payne DK, Biggs C, Tran KN et al (2000) Women’s regrets after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 7:150–154

Gartner R, Jensen MB, Nielsen J et al (2009) Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. JAMA 302:1985–1992

Gahm J, Wickman M, Brandberg Y (2010) Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with inherited risk of breast cancer—prevalence of pain and discomfort, impact on sexuality, quality of life and feelings of regret two years after surgery. Breast 19:462–469

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP et al (1989) Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for White females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 81:1879–1886

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Applied research program. National Cancer Institute. http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/. Accessed 31 Dec 2014

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program: research data (1973–2010). National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch. www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed 31 May 2016

Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC et al (1997) Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. Am J Roentgenol 169:1001–1008

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

R Development Core Team (2016) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 1 Jan 2016

Houssami N, Abraham LA, Kerlikowske K et al (2013) Risk factors for second screen-detected or interval breast cancers in women with a personal history of breast cancer participating in mammography screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 22:946–961

Parmigiani G, Berry D, Aguilar O (1998) Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet 62:145–158

Biswas S, Atienza P, Chipman J et al (2013) Simplifying clinical use of the genetic risk prediction model BRCAPRO. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139:571–579

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (HHSN261201100031C). The collection of cancer and vital status data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the US. For a full description of these sources, please see http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html. The collection of cancer incidence and vital status data used in this study was supported, in part, by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under Contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, Contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and Contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under Agreement U58-DP003862-01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health; Vermont Cancer Registry, Vermont Department of Health; Cancer Surveillance System of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, which is funded by Contract Nos. N01-CN-005230, N01-CN-67009, N01-PC-35142, HHSN261201000029C, and HHSN261201300012I from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute with additional support from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the State of Washington; New Hampshire State Cancer Registry supported in part by Cooperative Agreement U55/CCU-121912 awarded to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Public Health Services, Bureau of Disease Control and Health Statistics, Health Statistics and Data Management Section; North Carolina Central Cancer Registry, which is partially supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement DP12-120503CONT14; Colorado Central Cancer Registry, which is partially supported by the Colorado State General Fund and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Program of Cancer Registries) under Cooperative Agreement U58000848; New Mexico Tumor Registry supported, in part, by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Contract NO1-PC-35138 and by the University of New Mexico Cancer Center, a recipient of NCI Cancer Support Grant P30-CA118100. We thank the participating women, mammography facilities, and radiologists for the data they have provided for this study. A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/. We thank Linn Abraham for providing BCSC data-related support. We are also thankful to an anonymous reviewer for providing constructive comments. They have led to an improved version of the paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number R21 CA186086).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and endorsement by the State of California, the California Department of Public Health; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, M., Euhus, D., Onega, T. et al. A model for individualized risk prediction of contralateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 161, 153–160 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-4039-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-4039-x