Abstract

Submersed aquatic plants have a key role in maintaining functioning aquatic ecosystems through their effects on the hydrological regime, sedimentation, nutrient cycling and habitat of associated fauna. Modifications of aquatic plant communities, for example through the introduction of invasive species, can alter these functions. In the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, California, a major invasive submersed plant, Brazilian waterweed Egeria densa, has become widespread and greatly affected the functionality of the submersed aquatic plant community. Rapid assessments of the distribution and abundance of this species are therefore crucial to direct management actions early in the season. Given the E. densa bimodal growth pattern (late spring and fall growth peaks), summer assessments of this species may indicate which and where other submersed species may occur and fall assessments may indicate where this and other species may occur in the following spring, primarily because the Delta’s winter water temperatures are usually insufficient to kill submersed aquatic plant species. We assessed community composition and distribution in the fall of 2007 and summer of 2008 using geostatistical analysis; and measured summer biomass, temperature, pH, salinity, and turbidity. In the fall of 2007, submersed aquatic plants covered a much higher proportion of the waterways (60.7%) than in the summer of 2008 (37.4%), with a significant overlap between the seasonal distribution of native and non-native species. Most patches were monospecific, and multispecies patches had significantly higher dominance by E. densa, co-occurring especially with Ceratophyllum demersum. As species richness of non-natives increased there was a significant decrease in richness of natives, and of native biomass. Sustained E. densa summer biomass negatively affected the likelihood of presence of Myriophyllum spicatum, Potamogeton crispus, and Elodea canadensis but not their biomass within patches. Depth, temperature and salinity were associated with biomass; however, the direction of the effect was species specific. Our results suggest that despite native and invasive non-native submersed plant species sharing available niches in the Delta, E. densa affects aquatic plant community structure and composition by facilitating persistence of some species and reducing the likelihood of establishment of other species. Successful management of this species may therefore facilitate shifts in existing non-native or native plant species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Submersed plant species are particularly important to aquatic environments because they function as service providers (e.g., Duarte 2000) and ecosystem engineers (Jones et al. 1994; Jones et al. 1997). Submersed aquatic plants provide erosion stabilization (Gurnell et al. 2006), water retention, facilitate nutrient cycling, and provide habitat to associated faunal communities (de Groot et al. 2002; Duarte 2000). For example, submersed plants can affect the availability of oxygen in aquatic ecosystems, which in turn can have cascading impacts on nutrient cycling and habitat (Caraco et al. 2006; Caraco and Cole 2002; Rybicki and Landwehr 2007). Submersed aquatic plant communities also trap floating sediment particles, raise river bed levels by increasing sedimentation rates, increase water clarity, impede light penetration, steepen vertical temperature gradients, decrease river water velocity, alter flow-patterns, and ultimately change the banks of river channels from lotic to lentic systems (Jones et al. 1994; Jones et al. 1997; Rybicki and Landwehr 2007). However, irreversible changes in aquatic environments can occur if these traits/services are exacerbated by the over-abundance of specific species, such as non-native invasive species.

Non-native invasive species are species from a different geographical location whose traits often allow them to out-compete native species, through fast growth, restricting resources available to natives, or directly competing with them for space (Blumenthal and Hufbauer 2007). However, non-native species are not uniformly detrimental, as they may facilitate spread of native species by engineering the ecosystem (Rodriguez 2006), or may improve ecosystem function for associated fauna, such as waterfowl (Rybicki and Landwehr 2007). Further native species can also become invasive. We distinguish between the two types of species dynamics by naming “invasive species” native or non-native species that have negative effects, and the less aggressive as just native or non-native species. Invasions of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta have altered native species composition (Cohen and Carlton 1998; Nobriga et al. 2005). In the Delta, the most prominent non-native invasive submersed plant species is Brazilian waterweed Egeria densa (Anderson 1990), which is reported to have displaced most of the native submersed aquatic plant species within the system (Lund et al. 2007). E. densa is actively managed in parts of the central Delta (e.g. Franks Tract), and these actions are likely to reduce areal cover of this species (Santos et al. 2009) and could eventually change the composition back to a native species dominated community. Management of E. densa is complicated by its bimodal growth periods, late spring and autumn, (Pennington and Sytsma 2009), and by the large spatial extent of the Delta. This unique growth pattern would require multiple management actions throughout the year to overcome its competitive growth advantage, which would increase management costs substantially. Seasonal assessments of the spatial distribution and abundance of submersed species may aid defining management goals throughout the year, especially if matched with species lifecycles. For example, Woolf and Madsen (2003) reported that in Southern Minnesota, Potamogeton crispus turions sprout in late fall, but exhibit rapid growth the following spring; they suggest that early spring may be the optimal time for management. Similarly, summer assessments of E. densa distribution and abundance may indicate which and where it and other submersed species may occur, whereas fall assessments may indicate where E. densa and other species may occur in the following spring, especially because the winter water temperatures in the Delta are usually insufficient to kill submersed aquatic plant species (Cook and Urmi-König 1984; Mony et al. 2007; Van Nes et al. 2002). Furthermore, since species such as Stuckenia pectinata and Potamogeton nodosus produce specialized over wintering structures (tubers and winter buds, respectively) in late summer-fall in the sediment, sprouting of these propagules often results in recruitment at the same site the following spring (Sculthorpe 1965).

Spatially, the distribution and abundance of submersed plants is limited by anaerobic respiration (Blom and Voesenek 1996; Sand-Jensen et al. 1982; Vartapetian and Jackson 1997), low light penetration in the water column (Madsen and Sand-Jensen 1991), low nutrient availability (Pagano and Titus 2007; Vadstrup and Madsen 1995), competitive interference from functionally similar submersed species (Chambers and Prepas 1990), and from floating and emergent plant communities (Scheffer et al. 2003). Several techniques have been used to obtain reliable estimates of submersed plant distributions (Best 1981; Champion and Tanner 2000; Marshall and Lee 1994; Vis et al. 2003). The advent of spatial technology such as aerial photography and other remote sensing technologies (Marshall and Lee 1994; Vis et al. 2003), and powerful geostatistics tools such as kernel density estimators (Brunsdon 1995; Worton 1989), make it possible to ally field measurements with large scale assessments. Thus, there is a need to correctly estimate submersed aquatic plant species spatial distribution, plant community composition and biomass, and to understand their interactions and constraints due to the biophysical conditions in the environment.

To assess the effects of seasonal species-specific distributions, we examined the spatial distribution of the submersed aquatic species at a regional scale in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta during the fall of 2007 and summer of 2008. Our objectives were to assess: (1) how the spatial distribution of species in the fall matches the distribution of species in the following summer; (2) assess to what extent the non-native and native species are co-distributed and co-occurring; and (3) to determine how the presence and biomass of each species is affected by the presence of E. densa and by environmental parameters. We discuss the potential for using these results to inform management of the submersed aquatic community in this complex and highly invaded system, as well as other systems.

Methods

Study site

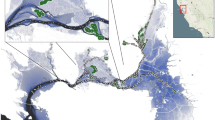

The study was conducted in the central area of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (20,776.3 ha) in California, including the convergence of the San Joaquin, the Sacramento, the Mokulumne, and the Cosumnes Rivers. This is a highly dynamic hydrological system due to the interaction of downstream freshwater inputs from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and the strong tidal and marine influence of the San Francisco Bay (Fig. 1), combined with active (pumped) management of water flows throughout the Delta. Note that the large bay in the central area of the Delta is Franks Tract, where herbicide was applied to control E. densa. Depths typically range from a few cm to 5 m depending upon bathymetry and tidal cycles.

Spring snowmelt from the Sierra generally increases turbidity and produces cool water conditions (10–15°C), whereas late summer low river flows lead to low turbidity and high temperatures (typically 17–22°C). These inputs have a great impact on the Delta water clarity and thus available light for submersed aquatic plants. Also, the gradient of saline and fresh water creates unique conditions for differential establishment of the submersed aquatic plant species. In addition, increasing anthropogenic activities in the Delta and its vicinity have dramatically changed natural flow patterns, regulated water input into the system (Nichols et al. 1986), and reduced water quality. These conditions, coupled with the introductions of floating, emergent and submersed plants over many decades, have substantially altered aquatic and riparian habitats. The native submersed aquatic plant assemblage includes coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), sago pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata), broadleaf sago pondweed (Stuckenia filiformis), common waterweed (Elodea canadensis), and American pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus) all of which face increasing competition from non-native E. densa, Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), Carolina fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana), and curlyleaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus).

Field surveys

We conducted field surveys in October 2007 and again in June 2008. Coincidently, this sampling period followed the April 2007 and 2008 applications of the systemic herbicide fluridone in Franks Tract (ca.1113 ha in the central Delta—Fig. 1) aimed at controlling E. densa. Locations were randomly selected throughout the Delta using ArcGIS and a previously existing distribution map of submersed aquatic vegetation of the Delta (Hestir et al. 2008). We selected 500 locations within the submersed aquatic vegetation distribution range and a similar number of locations in areas without submersed aquatic vegetation. At each location we identified the submersed aquatic plant species and documented their locations using a handheld Geographic Position System device with sub-meter accuracy (Geo XT, Trimble Inc., Sunnyvale, California, USA).

Submersed aquatic plant species sampling consisted of retrieving submersed aquatic plants using a long-handled, double-headed thatch rake (head width of 35 cm, with fourteen, sharp, flat 5.5 cm long tines on each side) following the protocol described in Kenow et al. (2007). The rake-sampling technique is effective in determining the presence and composition of submersed plants, especially when water clarity is poor. Rake sampling offers an alternative to other methods, like hydro-acoustic techniques, which are inaccurate in shallow waters (<0.7 m) (Kenow et al. 2007) and under dense submersed aquatic plant canopies (Vis et al. 2003), and cannot reliably distinguish species (Winfield et al. 2007), especially when they co-occur. At each site we collected one rake sample and identified each of the species. The relative quantity and relative proportion of individual species in each rake measurement were rated from 1 to 100 to estimate the dominance of each species, following the protocol described in Kenow et al. (2007).

In the summer 2008, we also collected the plants retrieved at a subset of rake sampling locations to measure the biomass of each species. Samples were brought to the lab, separated by species, washed to remove sediment, shaken to remove external water, and weighed. For each species, 10 subsamples of whole plants of each species were randomly selected and oven dried for 72 h after measuring fresh weight. The same samples were re-weighted to obtain dry weight. At each rake location we measured temperature (°C), conductivity (mS cm−1), pH, and turbidity (NTU) along depth profiles using a handheld YSI multiprobe sonde (YSI, Inc. Yellow Springs Ohio, USA). Local abiotic parameters were registered continuously across the water column, and average, minimum and maximum values were calculated for each location.

Data analysis—spatial autocorrelation

River systems are spatially autocorrelated due to their network structure (Wagner and Fortin 2005). For many statistical techniques, failure to account for autocorrelation violates the assumption of independent observations and may bias estimates of model parameters, inflate significance values of parameter estimates, and diminish the overall predictive performance of the statistical model (Legendre et al. 2002; Wintle and Bardos 2006). Since our goal was to assess spatial patterns of submersed aquatic plant species distribution and biomass, we used Moran’s index (I) coefficient (Eq. 1) (Moran 1950) to determine if our field data was affected by spatial autocorrelation.

where I(h) is the value of the index for interval class h, h is the distance between samples, N(h) is the number of observations in interval class h, z i is the measured value at point i, and z i+h is the measured value at point i + h (Moran 1950). The index value was then used to calculate Moran’s I statistic (Eq. 2).

In Eq. 2, u 1 and u 2 are the expected value and the variance of I(h), respectively, which are compared to those of a normal distribution under the null hypothesis that there is no spatial autocorrelation (Cheng and Stephens 1986; Epperson and Li 1996). This cross-autocorrelation coefficient measures the commonality in the spatial patterns of the variables (Fortin et al. 1989) and varies from −1 (perfect negative spatial autocorrelation) to 1 (perfect positive spatial autocorrelation), with values close to 0 representing no spatial autocorrelation. We used ArcGIS v 9.2 Spatial Statistics Spatial Autocorrelation Tool (ESRI, Inc., Redlands, California) to calculate the autocorrelation index. Since our dataset showed a random pattern (I = 0.01; z-score = 0.52, P > 0.05), we concluded the absence of spatial autocorrelation and performed additional analyses without excluding any of the field data points.

Data analysis—species spatial distribution

To obtain the spatial distribution of each plant species and pooled native and non-native plants, we used kernel-based geostatistical methods (Brunsdon 1995; Worton 1989) because they are well suited to river networks (Grant et al. 2007). Kernel estimators calculate a non-parametric utility distribution function based on a set of independent point locations, retrieving a multivariate probability surface for a given phenomenon (Brunsdon 1995; Worton 1989). As kernel-based predictions may reflect distribution patterns in areas surrounding the initial observation points, they are thus more adequate to map narrow stream channels and river networks. Further, kernel methods may resolve the multivariate complexity of aquatic systems processes, as they do not rely on distributional assumptions and can represent both linear and non linear processes (Sharma et al. 1997). We used the ArcGIS v 9.2 Spatial Analyst Kernel Density tool (ESRI, Redlands, California) to estimate the kernel probability surface for each submersed aquatic species. We set the search radius to be 500 m to allow contiguous distributions in the major Delta islands, and the output grid cell size to be 3 m. We then used the Spatial Analyst Math tool to overlay each of the species distributions and then estimate which areas are most likely to have higher species richness. We also calculated the area covered by each species, and for the sum of the native and the sum of the non-native species, and assessed if there were differences in area covered by each species, the sum of natives and the sum of non-natives between the fall and the summer.

To assess co-occurrence of native and non-native plants we first calculated the relative frequency of each species in the data set, the species richness at each location, the frequency at which species were found to co-occur and the overall community richness for the two sampling seasons. Relative frequency was estimated as the proportion of species i samples within the total dataset, and species richness was also estimated. We repeated the calculations after lumping the native species and non-native species into separate categories. We then tested for seasonal effects on species richness and dominance by each species using non-parametric Wilcoxon’s Chi-square (Zar 1999). We created a regression between the native richness against the non-native richness to assess co-occurrence. We also compared the number of times each species was found in monospecific patches or co-occurring with other species, and assessed seasonal differences in the co-occurrence rates.

Data analysis—community responses to Egeria densa and biophysical factors

To assess community responses to invasion, we converted fresh weight to dry weight for estimates of total plant biomass. We used linear regression analysis to obtain a prediction curve for dry weight for each species (see Appendix 1). We calculated the dry weight of each species in each of the rake samples and calculated total biomass, and native and non-native plant biomass. We then regressed native biomass against the non-native biomass to test whether the biomass of non-natives species may constrain the biomass production of native species. We repeated the analysis excluding sites where non-native species biomass was zero. We then tested for effects of non-native species richness on native biomass and that of native species on non-native biomass using non-parametric Wilcoxon’s Chi-square tests (Zar 1999).

Since E. densa was the most common species and the most common invasive species in this system, we used logistic regression to test the association of E. densa biomass with the presence of both the native and other non-native species. We tested logistic regression results with goodness-of-fit using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the receiver operating curve, which varies from 0 to 100 (Hanley and McNeil 1982) where values closer to 100 indicate better fit. Finally, we tested if species biomass was related to biophysical properties. We used multivariate stepwise least squares regression between biomass of each species and the biophysical parameters, and also tested for the combined effect of biophysical properties and biomass of E. densa, by adding dry weight of E. densa as a candidate variable (Zar 1999).

Results

We sampled submersed aquatic vegetation in 380 locations in the autumn of 2007 and 436 locations in the summer of 2008. Average species richness at sampling locations was not significantly different in the summer (1.63 ± 0.77 species) than in the fall (1.51 ± 0.66 species, χ2 = 1.48, P = 0.224).

Species occurrence and co-occurrence

E. densa was the most frequently detected species, and was present in more than 50% of the samples (Table 1) whereas C. demersum was the second most frequently detected species. P. nodosus, a native, was the least often detected species. About half the patches were monospecific in each season (57.6% in the fall and 55.3% in the summer, Table 2). E. densa was dominant (higher % cover of the rake) in multispecies patches in the fall than the summer, whereas almost all the other species were more dominant in the summer, except P. crispus and Stuckenia spp. (Table 3).

Most species co-occurred with up to 3 other species, especially during the summer (Fig. 3). Native and non-native plants showed similar frequencies of co-occurrence, and each were more likely to co-occur with only one other species at a given sampling site. However, two native species, E. canadensis and P. nodosus, showed higher frequencies of co-occurrence with more species (Fig. 2). The most commonly co-occurring species were E. densa and C. demersum, both in the fall (85 records) and the summer (119 records) (Table 2). C. demersum and E. densa also showed high frequency of co-occurrence with M. spicatum in both seasons.

Although most of the co-occurrence at the species level was observed between the native C. demersum and the non-native E. densa, this pattern is not reflected between native and non-native richness. Regression between richness of natives and non-natives was significant (F = 3.19, P = 0.05) and showed a significantly negative slope (slope = −0.166, P = 0.05) indicating that as richness of non-natives increases there is a decrease in the richness of natives. However, there was no significant relationship between native and non-native biomass in the summer (F = 0.67, P = 0.58). Biomass of native plants was significantly higher at either lower richness or absence of non-natives (χ 2Wilcoxon = 8.14, P = 0.04); and biomass of non-natives was significantly higher at either lower richness or absence of natives (χ 2Wilcoxon = 10.16, P = 0.006). Similar results were obtained when sites where non-native biomass was zero were excluded.

Species spatial distribution

The submersed plant canopy covered a large proportion of the waterways (Fig. 3), reaching 60.7% in the fall. Non-native plants covered an area 5 to 10% larger than the native plants, and this difference was greater in fall than in summer (59.8% by non-natives and 45.9% by natives; Table 1). Of the 388.35 ha of submersed plant canopy observed in the fall, 74.3% of this area (288.88 ha) was shared between native plants and non-native plants; in the summer the degree of co-occurrence was lower (91.9 ha of 239.6 ha of submersed plants, 38.2%). Further, native plants were found more often in the same areas (45.8% of the area) in the fall and summer than were non-natives (31% of same area). E. densa and C. demersum covered the largest area (Table 1) and their distribution showed the greatest overlap, both in fall and in summer (Table 2). Furthermore, C. demersum and Stuckenia spp. distribution area also showed high overlap, especially in the fall (Table 4).

Native and non-native species distribution for the central area of the Sacramento San Joaquin River Delta, October 2007 and June 2008 overlaid on the bathymetry of the study area. Distribution of the native and non-native species was estimated through spatial interpolation based on the kernel method. This method creates a utility distribution function that describes the probability of presence of natives and non-natives at any location of the study area, based on the presence and absence records from rake sampling. Lighter areas indicate areas with higher probability of presence and dark areas indicate zero probability of presence of native and non-native species

The kernel utility distribution function results shows that native and non-native species richness in the Delta is variable in space (Fig. 3). The areas with higher likelihood of finding native and non-native species were Big Break, Frank’s Tract, Rhode Island and Venice Cut (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, the native and non-native species spatial distribution in Franks Tract and Venice cut greatly changed from the fall to the following summer.

Plant community responses to Egeria densa and biophysical factors

High biomass of E. densa was associated with decreased presence of M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis (Table 5), but not with their biomass (Table 6). Depth was positively associated with E. densa, C. demersum, and E. canadensis biomass. Temperature most strongly correlated with the biomass of M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis, with positive effects on the first two species and negative on the latter. In addition, minimum temperature was associated with lower biomass of M. spicatum. Conductivity was positively associated with biomass of M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis, and there was a negative effect of average electrical conductivity in P. crispus. E. canadensis was the only species in which biomass was positively correlated with average pH. Finally, low turbidity was positively associated with E. densa and E. canadensis biomass (except for a negative effect of minimum turbidity); whereas turbidity was negatively associated with biomass of P. crispus. All models were significant and model performance was high, as observed by the high AUC values. Models explained between 12 and 54% of the variability of the data set.

Discussion

Submersed aquatic plant species act as ecosystem engineers and service providers (e.g., Rybicki and Landwehr 2007), whose impacts at the ecosystem level can be aggravated when these species have invasive traits. Our results show that the submersed plant community in the Delta is comprised of a mix of native and non-native species, co-occurring in similar locations. However, in sites with higher richness of natives, there is lower richness of non-natives and vice versa. The submersed aquatic plant community richness of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is similar to that reported for other river systems such as the Mississippi River (Kenow et al. 2007) and the tidal Potomac River (Rybicki et al. 2001), fluvial lakes such as the St. Laurence Lake (Quebec, Canada) (Vis et al. 2003), and lentic systems such as lakes in Maine (Hunter et al. 1986). However, in the Delta, the ratio of non-native to native plant species is higher (4:5) than that for these other systems (1:6, 1:14 or 2:5) (Hunter et al. 1986; Kenow et al. 2007; Rybicki et al. 2001; Vis et al. 2003). This indicates that the non-native species are a major and much larger component of submersed aquatic plant communities in this system than reported in others.

Native and non-native plants are widespread in the summer and fall, and non-native plants co-occur in many areas (Fig. 3). However, higher overlap between natives and non-natives was observed in the fall than in the following summer (Fig. 3). This appears to be mainly due to the secondary, late fall growth of E. densa, resulting in its covering a larger area at the end of the growing season. Indeed, E. densa was the most widespread species both spatially (Table 1), and temporally, with persistence from fall to summer (Table 4). This persistence no doubt accounts for increased dominance of E. densa in the fall than in the summer (Table 2). However, the herbicide-mediated control of E. densa in the central area of the study area that may reduce the presence of E. densa during the mid-late summer (ReMetrix 2008) resulting in its apparent increase in growth in the fall as it recovers. These control measures have been successful in reducing E. densa height and biovolume (Santos et al. 2009). We suggest that part of the reason for these changes in dominance and large decrease in cover from fall to summer is due to different life history traits of these submersed plants. In the Delta E. densa does not senesce in areas of warmer temperature and relatively constant flow (Pennington and Sytsma 2009). Thus, as native submersed plant species senesce in the fall, E. densa continues producing biomass, some of which persists through the winter. This pattern of sustained growth is also evident for other non-native species as M. spicatum, which initiates new growth from basal buds in the fall that gives it a competitive edge in early spring. As a consequence, the over wintering vegetative biomass can respond quickly to both increased day length and temperatures in early spring thus providing E. densa and M. spicatum with a competitive advantage over some native and non-native species.

Despite the extent of cover by E. densa in much of the available habitat in the Delta, it co-occurs with all other species (Table 2). A host of physical resources and life-history traits can account for this sustained co-occurrence, including (1) a response to spatially imposed constraints (nutrients, available spatial niches, etc.) that may restrict the spread of species; (2) replacement of other submersed species by E. densa, through competition with the native species (+/−: positive effect to E. densa and negative effect to native species); and (3) facilitation of other submersed species establishment by E. densa, growth and spread (+/0: positive effect to E. densa and null effect to other species). For example, the highest recorded co-occurrence was between E. densa and the native C. demersum (50% of the observations) in both seasons (Table 2). Since C. demersum lacks anchoring rooting capability (Denny 1972; Kautsky 1988) it is limited in flowing (and in this case also tidal) systems. However, E. densa canopy, creates more structure where C. demersum can anchor. C. demersum is also the species that shows the highest co-occurrence rates with other submersed plant species (Table 2), indicating that C. demersum is anchoring to preexisting submersed plants canopy. Exception may be made to those species with a filiform architecture and slippery canopy (Stuckenia spp. and P. nodosus), which are probably not conducive to anchoring C. demersum. Furthermore, E. densa stands reduce turbidity, thus increasing available light through the water column, which may promote C. demersum growth and persistence. Although a laboratory study suggests that senescing C. demersum in the sediment may release allelopathic substances that hinder the development of other neighboring submersed plant species except E. densa (Matheson et al. 2005), this has not been demonstrated under natural conditions. In the Delta, the recent establishment of E. densa in the early 1990’s may suggest that this species is still expanding its range and is thus potentially outcompeting and replacing other species (Lacoul and Freedman 2006). In addition, the gradual reduction of emergent plant canopy over the past 20 years resulting from the successful management of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) has probably released habitat available for submersed plants in general (CDBW 2005; Santos et al. 2009).

This study supported our initial hypothesis that the fall growth of E. densa would constrain the presence of other submersed aquatic plant species in the following summer. During the fall, E. densa in the Delta is known to grow ca. 0.7 cmd−1 (Tip growth rate ranges from 0.17 ± 0.6 cmd−1 in November and 0.68 ± 0.08 cmd−1 in April; stems elongated at a rate of 0.24 ± 0.04 cmd−1 in April and 0.09 ± 0.01 cmd−1 in August; buds grew up to 0.26 ± 0.08 cmd−1 Pennington 2007), which is one of the highest reported growth rates in submersed aquatic vegetation. Submersed plant growth is often limited by light availability, thus depth to the sediment has often been pointed out as a main constraining factor (Kautsky 1988). Our results also show an effect of depth on the growth of M. spicatum, C. demersum and E. canadensis, as well as E. densa. The first two species demonstrate lower biomass as average depth increases, indicating some light limitation at least in the case of M. spicatum (Kautsky 1988; Nichols and Shaw 1986; Titus et al. 1975), which is known to be a intermediate depth species (Nichols and Shaw 1986). Depth effects on C. demersum biomass may seem counter-intuitive since this plant lacks true roots; however, it is often entangled with species that are rooted to the sediment, such as E. densa and E. canadensis. The latter is one of the most depth tolerant species (Nichols and Shaw 1986), and our results are consistent with this pattern as we found higher biomass of E. canadensis at greater depths.

The growth of M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis was affected by water temperature. The Delta has relatively high water temperature (18–20°C in the summer), when compared with similar systems (Yates et al. 2008), and these increased temperatures seem to benefit the growth of non-natives such as M. spicatum (Titus et al. 1975) and P. crispus (Nichols and Shaw 1986). On the other hand, natives such as E. canadensis are negatively affected by higher water temperature. Optimal temperature for this species is not well understood, however it is known that E. canadensis does not thrive in competition with species adapted to warmer temperatures (Nichols and Shaw 1986). The negative effect of temperature on E. canadensis growth may be associated with this species preference for deeper waters, which likely have lower temperatures. Three species (M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis) also show higher growth in areas with higher conductivity, thus higher salinity. The Delta has a strong gradient of decreasing salinity from the west to the east (Jassby and Cloern 2000; Lucas et al. 2002), and thus it is not surprising that as species growth is positively influenced by salinity (Nichols and Shaw 1986), there is a higher cover in the western part of the study area (Fig. 3). Submersed species are known to have greater growth in more alkaline waters (Nichols and Shaw 1986), however, only E. canadensis growth is positively affected by pH.

Conclusions

Our study addressed three objectives about the distribution of native and non-native species in the fall and the following summer. We found that the species distribution in the fall tends to predict the distribution in the following spring, however, there is a higher distribution overlap between natives and non-natives species in the fall than in the following summer. E. densa has the most extensive spatial and temporal distribution with persistence from fall to summer due to its overwintering growth. This lack of winter dormancy is more common in the non-native species than the native species. Additionally we show that although all species co-exist, E. densa is found most frequently in monospecific stands or as the dominant species in mixed stands. We also show that the these species are differentially affected by the different environmental factors of depth, temperature, turbidity and salinity, in addition to management actions that target invasive species. All of these factors interact to determine how the presence and biomass of each species are affected.

The sequential colonization of altered systems by invading species is not new (e.g. Thiebaut 2007) and the Delta does not seem to be an exception. One hypothesis is that the region experiences an “invasional meltdown”, a process by which “multiple non-indigenous species facilitate one another’s invasion in various ways”, either through augmenting invasive success or the magnitude of their impact (Simberloff and Holle 1999). E. densa has been observed to cause this type of sequential replacement of aquatic species in New Zealand lakes (Wells et al. 1997), in the River Erft (Germany) (Hussner and Losch 2005), and in France (Thiebaut 2007). In each case, in shallow water E. densa displaced other submersed aquatic plant species after it became established. The chronology of plant invasions in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta suggests that M. spicatum was detected in the Delta in late 1950’s and became common by 1976 (Cohen and Carlton 1995). It was only in the late 1980’s to early 1990’s that both E. densa and P. crispus were recorded in the Delta (Cohen and Carlton 1995). M. spicatum may have facilitated the spread of E. densa by its earlier arrival in the system and modification of the river beds into shallower environments. E. densa is currently the most abundant submersed plant and occupies a large proportion of the Delta. E. densa has affected the physical properties of the environments where it exists (reduced turbidity and created higher light environments; Hestir et al. unpublished data), offers an anchoring support to C. demersum, and impedes the establishment of other submersed species, such as M. spicatum, P. crispus and E. canadensis. Unlike other areas where E. densa cannot occupy the near-surface high-light habitat, such as in New Zealand (Hofstra et al. 1999), populations in the Delta can occupy shallow water and high-light areas due to (1) twice daily tidal changes in water level, and (2) prevalence of epiphytes (primarily filamentous algae such as Cladophora spp. and Spirogrya spp.) that form dense cover at the surface of the water. The algal mats provide shade, which allows E. densa to thrive even under intense summer insolation.

Despite E. densa’s dominance in the Delta system, other non-native and native species persist. Continued reduction in E. densa biomass and cover through single-target management actions is likely to affect the plant community composition and may lead to shifts toward native or other invasive non-native plants such as P. crispus and M. spicatum. It is clear that non-native plant cover (primarily E. densa) was significantly reduced in Franks Tract, and areas south due to herbicide applications between 2007 and 2008 (Fig. 3). Thus, invasion events may not have reached a dead end, as new invaders are constantly arriving (Cohen and Carlton 1998) and since current management actions are focused only on E. densa. As in many aquatic ecosystems with increasing non-native species, the lack of historical, pre-invasion data hampers our understanding of the causality of current trends. At the regional scale, non-native species are increasing their dominance in the Delta’s submersed aquatic plant community, which may not represent a lack of functionality at the ecosystem level (since the non-native species are also service providers) but may trigger unexpected community composition and interactions.

References

Anderson LWJ (1990) Aquatic weed problems and management in the western United States and Canada. In: Pieterse AH, Murphy KJ (eds) Aquatic weeds, the ecology and management of nuisance aquatic vegetation, pp 371–391

Best EPH (1981) The submerged aquatic macrophytes in lake Maarsseveen I: species composition, spatial distribution and productivity. Aquat Ecol 15:72–81

Blom CWPM, Voesenek LACJ (1996) Flooding: the survival strategies of plants. Trends Ecol Evol 11:290–295

Blumenthal DM, Hufbauer RA (2007) Increased plant size in exotic populations: a common-garden test with 14 invasive species. Ecology 88:2758–2765

Brunsdon C (1995) Estimating probability surfaces for geographical point data—an adaptive kernel algorithm. Comput Geosci 21:877–894

Caraco NF, Cole JJ (2002) Contrasting impacts of a native and alien macrophyte on dissolved oxygen in a large river. Ecol Appl 12:1496–1509

Caraco N, Cole J, Findlay S, Wigand C (2006) Vascular plants as engineers of oxygen in aquatic systems. Bioscience 56:219–225

CDBW (2005) Water hyacinth control program. California Department of Boating and Waterways, Sacramento, p 42

Chambers PA, Prepas EE (1990) Competition and coexistence in submerged aquatic plant communities: the effects of species interactions versus abiotic factors. Freshw Biol 23:541–550

Champion PD, Tanner CC (2000) Seasonality of macrophytes and interaction with flow in a New Zealand lowland stream. Hydrobiologia 441:1–12

Cheng RCH, Stephens MA (1986) A goodness-of-fit test using Moran’s statistic with estimated parameters. Biometrika 76:385–392

Cohen AN, Carlton JT (1995) Non-indigenous aquatic species in a United States estuary: a case study of the biological invasions of the San Francisco Bay and Delta. United States Fish and Wildlife Services, Washington, DC

Cohen AN, Carlton JT (1998) Accelerating invasion rate in a highly invaded estuary. Science 279:555–558

Cook CDK, Urmi-König K (1984) A revision of the genus Egeria (Hydrocharitaceae). Aquat Bot 19:73–96

de Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ (2002) A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ 41:393–408

Denny P (1972) Sites of nutrient absorption in aquatic macrophytes. J Ecol 60:819–829

Duarte CM (2000) Marine biodiversity and ecosystem services: an elusive link. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 250:117–131

Epperson BK, Li T (1996) Measurement of genetic structure within populations using Moran’s I spatial autocorrelation statistics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:10528–10532

Fortin MJ, Drapeau P, Legendre P (1989) Spatial autocorrelation and sampling design in plant ecology. Vegetatio 83:209–222

Grant EHC, Lowe WH, Fagan WF (2007) Living in the branches: population dynamics and ecological processes in dendritic networks. Ecol Lett 10:165–175

Gurnell AM, Oosterhout MPV, Vlieger BD, Goodson JM (2006) Reach-scale interactions between aquatic plants and physical habitat: River Frome, Dorset. River Res Appl 22:667–680

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1982) The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36

Hestir EL, Khanna S, Andrew ME, Santos MJ, Viers JH, Greenberg JA, Rajapakse SS, Ustin SL (2008) Identification of invasive vegetation using hyperspectral remote sensing in the California Delta ecosystem. Remote Sensing of Environment (in press)

Hofstra DE, Clayton J, Green JD, Auger M (1999) Competitive performance of Hydrilla verticillata in New Zealand. Aquat Bot 63:305–324

Hunter ML, Jones JJ, Witham JW, Mingo TM (1986) Biomass and species richness of aquatic macrophytes in four Maine (USA) lakes of different acidity. Aquat Bot 24:91–95

Hussner A, Losch R (2005) Alien aquatic plants in a thermally abnormal river and their assembly to neophyte-dominated macrophyte stands (River Erft, Northrhine-Westphalia). Limnologica Eco Manag Inland Waters 35:18–30

Jassby AD, Cloern JE (2000) Organic matter sources and rehabilitation of the Sacramento—San Joaquin Delta (California, USA). Aquatic Conserv 10:323–352

Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M (1994) Organisms as ecosystems engineers. Oikos 69:373–386

Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M (1997) Positive and negative effects of organisms as physical ecosystems engineers. Ecology 78:1946–1957

Kautsky L (1988) Life strategies of aquatic soft bottom macrophytes. Oikos 53:126–135

Kenow KP, Lyon JE, Hines RK, Elfessi A (2007) Estimating biomass of submersed vegetation using a simple rake sample technique. Hydrobiologia 575:447–454

Lacoul P, Freedman B (2006) Environmental influences on aquatic plants in freshwater ecosystems. Environ Rev 14:89–136

Legendre P, Dale MRT, Fortin MJ, Gurevitch J, Horn M, Myers D (2002) The consequences of spatial structure for the design and analysis of ecological field surveys. Ecography 25:601–615

Lucas LV, Cloern JE, Thompson JK, Monsen NE (2002) Functional variability of habitats within the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: restoration implications. Ecol Appl 12:1528–1547

Lund J, Hanak E, Fleenor W, Howitt R, Mount J, Moyle P (2007) Envisioning futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco California

Madsen TV, Sand-Jensen K (1991) Photosynthetic carbon assimilation in aquatic macrophytes. Aquat Bot 41:5–40

Marshall TR, Lee PF (1994) Mapping aquatic macrophytes through digital image analysis of aerial photographs: an assessment. J Aquat Plant Manag 32:61–66

Matheson FE, de Winton MD, Clayton JS, Edwards TM, Mathieson TJ (2005) Responses of vascular (Egeria densa) and non-vascular (Chara globularis) submerged plants and oospores to contrasting sediment types. Aquat Bot 83:141–153

Mony C, Koschnick TJ, Haller WT, Muller S (2007) Competition between two invasive Hydrocharitaceae (Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) (Royle) and Egeria densa (Planch)) as influenced by sediment fertility and season. Aquat Bot 86:236–242

Moran PAP (1950) Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 37:17–23

Nes EHV, Scheffer MS, van-den-Berg MS, Coops H (2002) Dominance of charophytes in eutrophic shallow lakes—when should we expect an alternative stable state? Aquat Bot 72:275–296

Nichols SA, Shaw BH (1986) Ecological life histories of the three aquatic nuisance plants, Myriophyllum spicatum, Potamogeton crispus and Elodea canadensis. Hydrobiologia 131:3–21

Nichols FH, Cloern JE, Luoma SN, Peterson DH (1986) The modification of an estuary. Science 231:567–573

Nobriga ML, Feyrer F, Baxter RD, Chotkowski M (2005) Fish community ecology in an altered river Delta: spatial patterns in species composition, life history strategies, and biomass. Estuaries 28:776–785

Pagano AM, Titus JE (2007) Submersed macrophyte growth at low pH: carbon source influences response to dissolved inorganic carbon enrichment. Freshw Biol 52:2414–2420

Pennington TG (2007) Seasonal changes in allocation, growth, and photosynthetic responses of the submerged macrophytes Egeria densa Planch (Hydrocharitaceae) from Oregon and California. Ph.D. Dissertation, Portland State University, Portland

Pennington TG, Sytsma MD (2009) Seasonal changes in carbohydrate and nitrogen concentrations in Oregon and California populations of Brazilian Egeria (Egeria densa). Invasive Plant Sci Manag 2:120–129.

ReMetrix (2008) 2007 Monitoring aquatic herbicide treatment and efficacy on Egeria densa Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, CA. Annual Summary Report with Maps, Graphs and Statistics, ReMetrix, Carmel, p 57

Rodriguez LF (2006) Can invasive species facilitate native species? Evidence of how, when, and why these impacts occur. Biol Invasions 8:927–939

Rybicki NB, Landwehr JM (2007) Long-term changes in abundance and diversity of macrophyte and waterfowl populations in an estuary with exotic macrophytes and improving water quality. Limnol Oceanogr 52:1195–1207

Rybicki NB, McFarland DG, Ruhl HA, Reel JT, Barko JW (2001) Investigations on the availability and survival of submersed vegetation propagules in the tidal Potomac River. Estuaries 24:407–424

Sand-Jensen K, Prahl C, Stokholm H (1982) Oxygen release from roots of submerged aquatic macrophytes. Oikos 38:349–354

Santos MJ, Khanna S, Hestir EL, Andrew ME, Rajapakse SS, Greenberg JA, Anderson LWJ, Ustin SL (2009) Use of hyperspectral remote sensing to evaluate efficacy of aquatic plant management in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, California. Invasive Plant Sci Manag 2:216–229

Scheffer M, Szabo S, Gragnani A, EHv Nes, Rinaldi S, Kautsky N, Norberg J, Roijackers RMM, Franken RJM (2003) Floating plant dominance as a stable state. Proc Nat Acad Sci 100:4040–4045

Sharma A, Tarboton DG, Lall U (1997) Streamflow simulation: a non-parametric approach. Water Resour Res 33:291–308

Simberloff D, Holle BV (1999) Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biol Invasions 1:21–32

Thiebaut G (2007) Invasion success of non-indigenous aquatic and semi-aquatic plants in their native and introduced ranges. A comparison between their invasiveness in North America and France. Biol Invasions 9:1–12

Titus J, Goldstein RA, Adams MS, Mankin JB, O’Neill RV, Weiler PR Jr, Shugart HH, Booth RS (1975) A production model for Myriophyllum spicatum L. Ecology 56:1129–1138

Vadstrup M, Madsen TV (1995) Growth limitation of submerged aquatic macrophytes in inorganic carbon. Freshw Biol 34:411–419

Vartapetian BB, Jackson MB (1997) Plant adaptations to anaerobic stress. Ann Bot 79:3–20

Vis C, Hudon C, Carignan R (2003) An evaluation of approaches used to determine the distribution and biomass of emergent and submerged aquatic macrophytes over large spatial scales. Aquat Bot 77:187–201

Wagner HH, Fortin MJ (2005) Spatial analysis of landscapes: concepts and statistics. Ecology 86:1975–1987

Wells RDS, de Winton MD, Clayton JS (1997) Successive macrophyte invasions within the submerged flora of Lake Tarawera, Central North Island, New Zealand. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 31:449–459

Winfield IJ, Onoufriou C, O’Connell MJ, Godlewska M, Ward RM, Brown AF, Yallop ML (2007) Assessment in two shallow lakes of a hydroacustic system for surveying aquatic macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 584:111–119

Wintle BA, Bardos DC (2006) Modeling species-habitat relationships with spatially autocorrelated observation data. Ecol Appl 16:1945–1958

Woolf TE, Madsen JD (2003) Seasonal biomass and carbohydrate allocation patterns in Southern Minnesota curlyleaf pondweed populations. J Aquat Plant Manag 41

Worton BJ (1989) Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology 70:164–168

Yates D, Galbraith H, Purkey D, Huber-Lee A, Sieber J, West J, Herrod-Julius S, Joyce B (2008) Climate warming, water storage, and Chinook salmon in California’s Sacramento Valley. Climatic Change 91:335–350

Zar JH (1999) Biostatistical analysis. New Jersey, 663 pp

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the California Department of Boating and Waterways Agreement 03-105-114. We would like to acknowledge D. Kratville, J.R.C. Leavitt, P. Akers, and the field crews of the California Department of Boating & Waterways; E. Hestir, S. Khanna, J. Greenberg, S. Kefauver, M. Andrew, P. Haverkamp, P. Tittman, M. Whiting for assistance in the field. We also thank R. McIlvaine and G. Scheer for administrative support. Special thanks are due to M. Andrew for insightful comments and discussion. We would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief Dr. Dan Simberloff and two anonymous reviewers whose comments were extremely valuable and greatly improved this manuscript to its current form.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

See Table 7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, M.J., Anderson, L.W. & Ustin, S.L. Effects of invasive species on plant communities: an example using submersed aquatic plants at the regional scale. Biol Invasions 13, 443–457 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9840-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9840-6