Abstract

Aegagropila linnaei, a freshwater green macroalga, had been abundant in several locations in The Netherlands before the 1960s. Both the ‘lake ball’ form of this alga and dense unattached mats floating over the sediment have been described from these locations. After 1967, this species has not been recorded anymore from The Netherlands. In 2007, several historical collection sites were surveyed for extant populations of A. linnaei. All habitats have changed drastically during the last 50 years and were affected severely by eutrophication. Populations of A. linnaei seem to have become extinct in all but one location (Boven Wijde, province Overijssel), where we found very small amounts of attached filaments. The attached form had not been reported previously from The Netherlands. Environmental conditions do not seem suitable anymore to maintain extensive unattached growth forms including the enigmatic lake balls, and the species must be regarded as threatened in The Netherlands and we propose to include A. linnaei in a national red list. The decline of populations elsewhere is reviewed and discussed in this paper. In addition to morphological identification of the attached filaments, partial sequences of the nuclear large subunit rDNA were generated and compared with different growth forms and habitats from several other locations outside The Netherlands. The sequences confirm the identity of the Dutch material and indicate very little divergence both between populations in different locations and between different growth forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The green macroalga Aegagropila linnaei Kützing (Cladophorophyceae) occurs in freshwater and some brackish environments and has essentially a palaearctic distribution (van den Hoek 1963; Pankow 1965). The simple morphology consists of stiff, branched uniseriate filaments and is very similar to members of the related genus Cladophora Kützing. A. linnaei is morphologically distinct from Cladophora spp. by the lateral or subterminal, often opposite, sometimes serial insertion of branches; irregular cell shape and unrestricted insertion positions of branches especially in the basal parts; and development of rhizoids from the base of cells which can produce terminal haptera (van den Hoek 1963; Leliaert and Boedeker 2007; Soejima et al. 2008). The species is presumed to reproduce mainly or entirely vegetatively by means of fragmentation (Brand 1902; Acton 1916; van den Hoek 1963). Based on morphological similarities, the species was placed in the genus Cladophora (as C. aegagropila (L.) Rabenhorst, van den Hoek 1963), but has recently been recognized as its own monotypic genus based on molecular evidence. It is placed in a separate clade that is sister to the orders Siphonocladales and Cladophorales, together with several other species-poor, predominantly freshwater genera such as Arnoldiella, Basicladia, Pithophora and Wittrockiella (Hanyuda et al. 2002; Leliaert et al. 2003).

Aegagropila linnaei can occur in several different growth forms, depending on environmental conditions (Waern 1952; Sakai and Enomoto 1960; Niiyama 1989). The species is best known for the formation of spherical balls several centimeters in diameter, the so-called lake balls, marimo (in Japan), or moss balls (in aquarium shops). These balls consist of many interwoven filaments. In Japan, the lake balls are very popular and have been designated a ‘special natural monument’ (Kurogi 1980). The ball forms have also become very popular in the aquarium trade.

The species can grow as unattached mats, floating above the substrate in shallow water, or as attached epilithic or epizoic filaments. Different theories about the formation of the ball form have been proposed, but it is generally assumed that the formation is a mixture of mechanic processes through water motion and features intrinsic to the species that help entanglement, such as the stiff texture, the formation of rhizoids, and the growth pattern following the abrasion of apical cells while rolling on the sediment (Wesenberg-Lund 1903; Acton 1916; van den Hoek 1963; Kurogi 1980; Niiyama 1989; Einarsson et al. 2004). It has been shown in culture experiments that stable balls can be produced when exposing loose filaments to a rolling motion (Nakazawa 1973).

A recent study from Japan also contributing to the conservation of A. linnaei and the management of its habitats indicates the possibility of genetic differentiation between different growth forms, and it emphasizes the necessity to extend conservation efforts to epilithic populations as well (Soejima et al. 2008).

Floating balls or unattached mats of A. linnaei have been found in several locations in The Netherlands: in Lake Naardermeer in North Holland (Koster 1959), in the lake system Loosdrechtse Plassen in North Holland (Koster 1959), in Lake Zwarte Broek in Friesland (Kops et al. 1911; Koster 1959), and in several parts of the lake system ‘De Wieden’ in the province Overijssel (Koster 1959; Segal and Groenhart 1967). Since then, Aegagropila balls or mats have not been reported again, so the last record of this species in The Netherlands is more than 40 years old. Attached forms had never been reported from The Netherlands.

Taking into account the long period during which A. linnaei had not been recorded and the changes in the environment in the meantime, it was assumed that this species had disappeared from its original habitats. Therefore, the historical collection sites were visited to check whether this species and its characteristic ball-shaped growth form still might exist in The Netherlands. We further discuss the situation and threat to this species elsewhere. Partial LSU rDNA sequences were generated to verify morphological identifications of putative material of A. linnaei and to investigate possible genetic divergence between different growth forms, as well as between populations from different habitats and locations.

Materials and methods

Herbarium and literature survey of Dutch locations

During a survey on the global distribution of A. linnaei based on herbarium specimens, it became obvious that there are very few recent collections of this species in general, with the majority of the herbarium specimens being more than 100 years old. For findings from The Netherlands that are neither mentioned in available literature nor deposited in the collections of herbaria, we contacted several Dutch organizations that carry out monitoring of aquatic vegetation and/or water quality in different areas of The Netherlands. These include Stichting Natuurmonumenten, Stichting Floron, Landelijk Informatiecentrum Kranswieren (LIK), Waternet, Waterschap Reest and Wieden, and Wetterskip Fryslân. Also several boat rental businesses and dive clubs in The Netherlands were contacted for possible amateur sightings of ‘lake balls’. The locations in the resulting list (Table 1) were the candidates for field work to search for extant populations in The Netherlands.

Field work

We visited six locations during seven field trips, covering most places where A. linnaei had been found previously (Fig. 1), plus one additional location that was pointed out by amateur divers (‘De Groene Heuvels’). The Beulaker Wijde, the Duinigermeer, and the Zuideindigerwiede could not be visited due to time constraints. Information about the locations and employed field methods is summarized in Table 2. Field methods depended on local conditions, i.e., size of the lake, shore accessibility, underwater visibility, and availability of a boat. Wherever information on the precise location of previous collections was available, field work was focused in those areas of the lakes (i.e., the Mennegat in the Naardermeer and the A. Lambertskade in the Loosdrechtse Plassen). If the underwater visibility was too poor for snorkeling or SCUBA diving, the sampling consisted of dredging with a standard garden rake using a boat or wading in shallow water, and shore observations. Special attention was paid to submerged solid substrates, i.e., mussel shells and stones. Shore observations were concentrated to areas with reed stands and leeward bays or shores. Material resembling A. linnaei was brought back to the laboratory and examined under a microscope. Verified material of A. linnaei was vouchered and stored in L (the National Herbarium of The Netherlands, Leiden branch; see Table 3 for details).

DNA sequence analysis

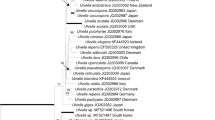

Partial large subunit (LSU) rDNA sequences from six specimens of A. linnaei were analyzed to check the morphological identifications, covering different growth forms, habitats, and locations (including one Dutch site). Sample and collection information, voucher specimens, and GenBank accession numbers are given in Table 3. DNA was extracted from fresh material or specimens that had been desiccated in silica gel after collection (Chase and Hills 1991). Fresh material was processed as herbarium vouchers now deposited in L, plus additional liquid preservation in formaldehyde solution or ethanol. Total genomic DNA was isolated using the Chelex method (Goff and Moon 1993).

PCR amplifications were performed in a Biomed thermocycler with an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 5 min followed by 31 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 57°C, and 30 s at 72°C, with a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. The reaction volume was 25 μl and consisted of 0.1–0.4 μg genomic DNA, 1.25 nmol of each dNTP, 6 pmol of each primer, 2.5 μl of 10× reaction buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Qiagen), 1 μl BSA (2.5%), 17.7 μl H2O, and one unit of Taq polymerase (Qiagen). The first ~590 nucleotides of the LSU rDNA were amplified using the universal primers C′1 forward (5′-ACCCGCTGAATTTAAGCATAT-3′) and D2 reverse (5′-TCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3′; Hassouna et al. 1984; Leliaert et al. 2003). Amplifications were checked for correct size by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and subsequent staining with ethidium bromide. PCR products were purified with Montage PCR filter units (Millipore) or with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation) following the manufacturers’ protocols. Cleaned PCR products were sent to Macrogen, South Korea, for sequencing. The final consensus sequences were constructed with Sequencher 4.0.5 software (GeneCodes), subsequently aligned by eye in Se-Al v2.0a11 (Rambaut 2007) and submitted to GenBank (see Table 3).

Results

Herbarium and literature survey of Dutch locations

In total, 27 herbarium specimens of A. linnaei from Dutch locations could be traced. The collection in L (see Holmgren et al. 1990 for herbarium abbreviations) contains the majority of the material (11 specimens) and covers six locations in The Netherlands: Boven Wijde, Molengat, Zuideindigerwiede (all in an area called ‘De Wieden’, province Overijssel), Mennegat (Naardermeer, province North Holland), Wijde Blik (Loosdrechtse Plassen, province North Holland), and Zwarte Broek (near Roodkerk, province Friesland; Fig. 1). Additional specimens from the same locations of A. linnaei were housed in nine other herbaria (BM, BR, BRNU, LD, M, NY, PC, UBC, W). All herbarium specimens consist of unattached material, either ball-shaped or free-floating entangled masses. The collections span a 110 year period (1852–1962). Lake balls of this kind have also been reported in the literature from the Beulaker Wijde (Koster 1959) and Duinigermeer (Segal and Groenhart 1967), both in the ‘De Wieden’ area, province Overijssel. All locations are listed with additional information in Table 1. None of the contacted monitoring organizations had ever recorded A. linnaei. While most reports of ‘lake balls’ by boat rental businesses could be instantly regarded as being cyanobacterial by how they were described, there was initially convincing information given by amateur divers about Aegagropila-like balls in recent years from the Lake ‘De Groene Heuvels’.

Field work

The results of the field trips are summarized in Table 2. All historical locations of A. linnaei gave a similar impression with signs of eutrophication as indicated by poor underwater light climate and organic muddy sediments, except the Naardermeer. Unattached mats or balls of A. linnaei were not encountered anywhere. Only in the Boven Wijde (province Overijssel), a single attached tuft of A. linnaei was found on a shell of the freshwater shellfish Anodonta anatina (Fig. 2). The filaments displayed all the typical morphological characters of the species (van den Hoek 1963; Leliaert and Boedeker 2007): subterminal insertion of branches (Fig. 2a–d), rhizoids in distal parts of the thallus (Fig. 2a), often opposite branches (Fig. 2b), irregular cell shape and unrestricted insertion of branches in basal parts (Fig. 2c), and serial insertion of branches (Fig. 2d).

Morphological characters of Aegagropila linnaei from the Boven Wijde, The Netherlands. a Subterminal insertion of branches and a rhizoid sprouting from the distal part of the thallus. b Subterminal insertion of branches, opposite branching, irregular cell shape. c Irregularly shaped cells in the basal region, branching from the middle of a cell, thick cell walls. d Serial insertion of branches. Scalebars = 100 μm

The Naardermeer differed from the other sampling locations in having clearer water and a dense charophyte vegetation. Hundreds of unattached ball-shaped colonies of the cyanobacterium Nostoc pruniforme C. Agardh ex Bornet & Flahault were floating just above the bottom, resembling A. linnaei underwater (Fig. 3a, b).

The recreational Lake ‘De Groene Heuvels’, even though not a location from which the occurrence of A. linnaei had been reported earlier, was visited to verify reports of ‘lake balls’ by divers. Ball-shaped colonies of the ciliate Ophridium versatile (Müller) Ehrenberg and the cyanobacteria Rivularia sp., Gloeotrichia pisum (C. Agardh) Thuret, and Tolypothrix polymorpha Lemmermann were observed. The latter formed free-floating, dark-green tufts up to 4 cm in diameter (Fig. 3c, d), resembling A. linnaei. A. linnaei was not found and there is no evidence that the species ever occurred there.

DNA sequences

All six samples of A. linnaei (see Table 3), representing different growth forms, habitats, and locations showed identical nucleotide sequences in the LSU, except for one point mutation at position 178 (reference sequence: Chlorella ellipsoidea Gerneck, GenBank no.: D17810) in two samples. One of the two sequences of A. linnaei from the brackish Pojo Bay, Finland (L69, unattached populations) and the sequence from The Netherlands (AI15, attached) displayed an A instead of a G at that position. Close examination of the electropherograms at this variable position showed underlying peaks matching the corresponding base of the other sequence in three out of the six sequences, suggesting that the observed differences from direct cycle sequencing might be attributable to intragenomic variation.

Discussion

There are no Dutch records of the enigmatic green alga A. linnaei dated later than 1962 preserved in any official herbarium. The last report of the species in the literature is dated 5 years later (Segal and Groenhart 1967). After 1967, there are no reports until our present study. During a survey of the collections of A. linnaei from 29 herbaria, only 9 out of more than 1,000 specimens had been collected in Europe in the last 30 years (data not shown). Even though this reflects a change in the tradition of collecting and depositing freshwater algal specimens during the last century to some degree, the obvious anthropogenic changes in the natural habitats most probably have led to a decline in populations in The Netherlands and elsewhere.

Field work

Searching for unattached algae floating over the bottom, such as A. linnaei, in peaty or eutrophicated lakes with poor visibility is very difficult. Although the lake balls have been frequently reported to occur in large numbers, the populations often seem to be restricted to a specific part of the lakes (Koster 1959; Pankow 1965; Kurogi 1980; Pankow and Bolbrinker 1984; Einarsson et al. 2004). In those areas, light supply, depth, sediment type, slope, and water movements obviously allow the unattached forms to thrive. Even when targeting typical habitats such as shallow sandy bottoms, reed belts, downwind bays or specifically mentioned historic collection sites, and deploying a range of methods, populations could be entirely missed. This is even more likely if the unattached forms (mats and balls) have disappeared and if the remaining population of attached individuals is small and patchy. Finding the alga on one single unionid mussel shell in one location may suggest a small and scattered population. A. linnaei has also been found attached on unionids in Japan (Niiyama 1989; Wakana et al. 2001, 2005). Growing on shellfish in shallow water might be one way how populations can survive when not enough light penetrates into deeper waters anymore due to eutrophication effects.

Growth forms and habitats

The range of different growth forms, the morphological plasticity of the species, and the range of habitats have led to the description of a large number of species and forms, but these were later synonymized by van den Hoek (1963). Lakes are generally regarded as the typical habitat of A. linnaei, and the species can be locally abundant or even dominant (van den Hoek 1963). Attached populations also occur in several rivers. The epilithic form has been found in the Seine and the Moine in France (van den Hoek 1963), in the river Sasso in Switzerland (van den Hoek 1963), the Fényes spring in Hungary (Palik 1963), in the Oslava river in the Czech Republic (as Cladophora moravica (Dvořák) Gardavský 1986), and in the rivers Tees, Tyne, Tweed, and Wear in the UK (Holmes and Whitton 1975; Whitton et al. 1998). Another very different habitat of A. linnaei is the brackish northern part of the Baltic Sea, where it grows mostly attached on rocks. A. linnaei is widespread and locally abundant in the Gulf of Bothnia (Waern 1952; van den Hoek 1963; Bergström and Bergström 1999), where the salinity is below 6 psu.

Two ball-shaped samples of A. linnaei from two lakes as distant as Japan and Sweden were previously shown to have identical small subunit (SSU) rDNA gene sequences (Hanyuda et al. 2002). Here, we present six partial sequences of the more variable large subunit (LSU) rRNA gene. These sequences represent the three different growth forms (ball-shaped, unattached mats, epilithic/epizoic), a range of habitats (brackish and freshwater) and distant locations (Table 3). All sequences are identical except for one shared point mutation in the sample from The Netherlands and in one of the samples from Finland, confirming that A. linnaei has a wide distribution and spans a range of habitats. Therefore, it seems justified to refer to all growth forms as one species. An isozyme study of A. linnaei populations in Japan revealed genetic differentiation and limited gene flow between attached and unattached populations, emphasizing the need for conservation efforts for all growth forms (Soejima et al. 2008).

Eutrophication in The Netherlands

All lakes in The Netherlands where A. linnaei had been collected in the past were severely eutrophicated, starting around the 1960s and 1970s. Characteristic for these eutrophicated systems were the reduction in water transparency and the absence of charophyte vegetation (Leentvaar and Mörzer Bruijns 1962; Maasdam and Claassen 1998; Riegman 2004; Boosten 2006; Kiwa Water Research 2007; Waternet, personal communication; W. Fryslân, personal communication). Restoration measures undertaken in the 1990s led to improved water quality and a return of charophyte vegetation only in the Duinigermeer (van Berkum et al. 1995), the Zuideindigerwiede (E. Nat, personal communication), and the Naardermeer (Boosten 2006), while restoration attempts have not improved the situation in the Loosdrechtse Plassen so far (Hofstra and van Liere 1992; Van Liere and Gulati 1992).

From the herbarium survey of locations worldwide and the potential natural state of those lakes, as well as from many literature reports, it is apparent that A. linnaei typically occurs in oligo to mesotrophic lakes, but can also occur in dystrophic and slightly eutrophic habitats. Only the attached form has been encountered sporadically in eutrophic or disturbed habitats, such as the rivers Seine and the Moine (van den Hoek 1963) or the Boven Wijde. Due to self-shading, the unattached forms need good light conditions to grow (Yoshida et al. 1994), and they might therefore be more sensitive to eutrophication due to the invariable deterioration in underwater light climate. A reduction in light availability has been shown to cause the decline in charophytes in eutrophicated lakes in Sweden (Blindow 1992). Another negative effect on submerged vegetation in eutrophicated waters can be damage by bottom feeding fish such as bream (ten Winkel and Meulemans 1984). In the case of A. linnaei, the change from sandy to muddy sediments in eutrophicated waters would have a negative impact, especially on the formation of balls. In addition to eutrophication, changes in hydrology and turbidity could also have a strong negative effect on unattached growth forms.

It is most likely that the populations of A. linnaei died out during the 1960s and 1970s in the Naardermeer, the Loosdrechtse Plassen, the Zuideindigerwiede, the Duinigermeer, the Molengat, and the Zwarte Broek, because of the effects of eutrophication. The finding of the species in the eutrophicated Boven Wijde might represent the remainder of a once larger population. An alternative, less likely, explanation is that A. linnaei could have become extinct everywhere in the 1970s and could have recently recolonized the Boven Wijde. There is no indication that habitats with an improved water quality such as the Naardermeer have been recolonised, and the recolonisation potential of the species might be very low. The restored Naardermeer seems like a suitable habitat for A. linnaei, as judged by the trophic level (mesotrophic), the charophyte vegetation, and especially the presence of Nostoc pruniforme (see Mollenhauer et al. 1999). Dispersal by water birds should theoretically make recolonization of suitable habitats possible (e.g., Schlichting 1960). On the other hand, the assumed small size of source populations, the rarity or complete absence of sexual reproduction (Soejima et al. 2008), and the very slow growth rates (van den Hoek 1963; personal observation.) reduce the likelihood of re-establishing populations. Fragmentation can be regarded as an efficient way of dispersal in some groups of algae. However, fragmentation as the only means of reproduction in a slow-growing organism such as A. linnaei, i.e., without any form of additional spore release, results in a low dispersal potential.

Decline and threat of Aegagropila linnaei

Aegagropila linnaei is seemingly extinct in most of the original locations in The Netherlands, where this species used to be quite abundant (see Table 2), as already reported for the Zuideindigerwiede (Segal and Groenhart 1967). Extinct populations have also been reported in the literature from the German Baltic Sea coast (Schories et al. 1996) and from Lake Galenbecker in northeastern Germany (Pankow 1985). In some instances, the ball form became extinct while the epilithic filamentous form still persisted, i.e., in Lake Zeller in Austria (Nakazawa 1974; Kann and Sauer 1982) and in Lake Akan in Japan (Wakana 1993; Wakana et al. 1996). Also this seems to be true for our study. A decline in population numbers and/or size is known from Lake Myvatn in Iceland (Einarsson et al. 2004), from Takkobu Marsh and other small swamp lakes in Japan (Wakana et al. 2001, 2005), and from Denmark, where the only population left occurs in Sorø Sø, Sjæland (R. Nielsen, personal communication). The observed decline in populations or the natural habitats being under threat led to the inclusion of the species in several national red lists or other conservation instruments. A. linnaei has a status as an endangered or protected species in Japan (Environment Agency of Japan 2000), Iceland (Á. Einarsson, personal communication), United Kingdom (provisional, Brodie et al. 2008), Germany (Ludwig and Schnittler 1996; Schories et al. 1996), Sweden (Gärdenfors 2005), Estonia (Lilleleht 1998), and Russia (Noskov 2000).

Eutrophication of aquatic systems is a common process worldwide and leads to the loss of unique habitats and a reduction in biodiversity (i.e., Bayly and Williams 1973). Restoration of affected water bodies once polluted is difficult, costly, and takes a long time. Even after restoration, ecosystems do not necessarily return to their original diversity and community structure (Entwisle 1997). If a habitat is successfully recolonized by A. linnaei, it might take decades before populations abundant enough will have built up to develop into the typical unattached mats or the lake balls. On the other hand, there is some indication for genetic differentiation between unattached and attached populations, as well as between different attached populations (Soejima et al. 2008). Therefore, loss of genetic diversity within A. linnaei might have already occurred in The Netherlands. The ball shapes that A. linnaei can produce have led to its popularity among scientists and naturalists, as well as in the aquarium trade, and Japanese society. This popularity could be the key to its conservation, and A. linnaei could possibly function as a flagship species of endangered freshwater algae other than desmids or charophytes. The situation in The Netherlands would certainly justify the inclusion of this species in a red list of The Netherlands or similar conservation instruments. At the moment, red lists only exist in The Netherlands for animals, fungi, vascular plants, and lichens. Red lists are possibly a first step in conservation measures, but it is impossible to protect individual algal species, thus only conservation of the natural habitats and catchment management could be successful. The future of A. linnaei in The Netherlands, and in some other regions, is uncertain.

Conclusions

Aegagropila linnaei had not been found in The Netherlands for more than 40 years, but is not extinct since the species was encountered again during a recent field survey, for the first time in the attached form. In all but one of the original locations, the species could not be found anymore. Taking into account the history of eutrophication in these lakes, it must be assumed that the species became extinct in those locations during the 1960s and 1970s. Unattached growth forms such as the enigmatic lake balls do not occur in The Netherlands anymore. Some of the original habitats have been restored and are candidates for possible recolonization, but the species might have a poor recolonizing potential. We propose to include this species in a national red list. In addition, it was shown that specimens with different growth forms from different locations and habitats have basically identical partial LSU rDNA sequences and either represent one single species or a complex of closely related cryptic species.

References

Acton E (1916) On the structure and origin of “Cladophora balls”. New Phytol 15(1–2):1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1916.tb07198.x

Bayly IAE, Williams WD (1973) Inland waters and their ecology. Longman, Camberwell

Bergström L, Bergström U (1999) Species diversity and distribution of aquatic macrophytes in the Northern Quark, Baltic Sea. Nord J Bot 19:375–383. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.1999.tb01131.x

Blindow I (1992) Decline of charophytes during eutrophication: comparison with angiosperms. Freshw Biol 28:9–14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1992.tb00557.x

Boosten A (2006) Meer Meer; 13 jaar Herstelplan Naardermeer. Stichting Natuurmonumenten, ’s-Graveland

Brand F (1902) Die Cladophora-Aegagropilen des Süsswassers. Hedwigia 41:34–71

Brodie J, John DM, Tittley I, Holmes MJ, Whitton DB (2008) Important plant areas for algae. Plantlife International, Salisbury. Available from http://www.plantlife.org.uk/uk/plantlife-saving-species-publications.html. Accessed 07 May 2008

Chase MW, Hills HH (1991) Silica gel: an ideal material for field preservation of leaf samples for DNA studies. Taxon 40:215–220. doi:10.2307/1222975

Einarsson Á, Stefánsdóttir G, Jóhannesson H, Ólafsson JS, Gíslason GM, Wakana I, Gudbergsson G, Gardarsson A (2004) The ecology of Lake Myvatn and the River Laxá: variation in space and time. Aquat Ecol 38(2):317–348. doi:10.1023/B:AECO.0000032090.72702.a9

Entwisle TJ (1997) Algae. In: Scott GAM, Entwisle TJ, May TW, Stevens GN (eds) A conservation overview of Australian non-marine lichens, bryophytes, algae and fungi. Environment Australia, Canberra

Environment Agency of Japan (2000) Threatened wildlife of Japan—Red data book vol. 9: bryophytes, algae, lichens, fungi, 2nd edn. Tokyo. Also available via http://www.biodic.go.jp/english/rdb/rdb_e.html. Accessed 07 May 2008

Gardavský A (1986) Cladophora moravica (Dvořák) comb. nova and C. basiramosa Schmidle, two interesting riverine species of the green filamentous algae from Czechoslovakia. Arch Hydrobiol Suppl 73(1):49–77

Gärdenfors U (2005) The 2005 redlist of Swedish species. Artdatabanken, Uppsala

Goff L, Moon D (1993) PCR amplification of nuclear and plastid genes from algal herbarium specimens and algal spores. J Phycol 29:381–384. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1993.00381.x

Hanyuda T, Wakana I, Arai S, Miyaji K, Watano Y, Ueda K (2002) Phylogenetic relationships within Cladophorales (Ulvophyceae, Chlorophyta) inferred from 18S rRNA gene sequences, with special reference to Aegagropila linnaei. J Phycol 38:564–571. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.01151.x

Hassouna N, Michot B, Bachellerie JP (1984) The complete nucleotide sequence of mouse 28S rRNA gene. Implications for the process of size increase of the large subunit rRNA in higher eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 12:3563–3583. doi:10.1093/nar/12.8.3563

Hofstra JJ, van Liere L (1992) The state of the environment of the Loosdrecht lakes. Hydrobiol 233:11–20. doi:10.1007/BF00016092

Holmes NTH, Whitton BA (1975) Macrophytes of the river Tweed. Trans Bot Soc Edinb 42:369–381

Holmgren PK, Holmgren NH, Barnett LC (1990) Index herbariorum, part I: the herbaria of the world. New York Botanical garden, New York

Kann E, Sauer F (1982) Die “Rotbunte Tiefenbiocönose” Neue Beobachtungen in österreichischen Seen und eine zusammenfassende Darstellung. Arch Hydrobiol 95(1):181–195. doi:10.1007/BF00044482

Kiwa Water Research (2007) Natura 2000–gebied 95—Oostelijke Vechtplassen. Available via http://www.synbiosys.alterra.nl/natura2000/documenten/gebieden/095. Accessed 07 May 2008

Kops J, van Eeden FW, Vuyck L (1911) Flora batava (23). Martinus Nijhoff, ‘s-Gravenhage

Koster JT (1959) Groene wierballen in Nederlandse plassen. De levende Natuur 62:178–182

Kurogi M (1980) Lake ball “Marimo” in Lake Akan. Jap J Phycol 28:168–169

Leentvaar P, Mörzer Bruijns MF (1962) De verontreiniging van de Loosdrechtse Plassen en haar gevolgen. Levende Natuur 65:42–48

Leliaert F, Boedeker C (2007) Cladophorales. In: Brodie J, Maggs CA, John DM (eds) Green seaweeds of Britain and Ireland. British Phycological Society, London

Leliaert F, Rousseau F, De Reviers B, Coppejans E (2003) Phylogeny of the Cladophorophyceae (Chlorophyta) inferred from partial LSU rRNA gene sequences: is the recognition of a separate order Siphonocladales justified? Eur J Phycol 38(3):233–246. doi:10.1080/1364253031000136376

Lilleleht V (1998) Red data book of Estonia. Threatened fungi, plants and animals. Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia, Tartu. Available via http://www.zbi.ee/punane/english/index.html. Accessed 07 May 2008

Ludwig G, Schnittler M (1996) Rote Liste gefährdeter Pflanzen Deutschlands. Bundesamt für Naturschutz, Bonn-Bad Godesberg

Maasdam R, Claassen THL (1998) Trends in water quality and algal growth in shallow Frisian lakes, The Netherlands. Water Sci Technol 37(3):177–184. doi:10.1016/S0273-1223(98)00068-7

Mollenhauer D, Bengtsson R, Lindstrøm E-A (1999) Macroscopic cyanobacteria of the genus Nostoc: a neglected and endangered constituent of European inland aquatic biodiversity. Eur J Phycol 34(4):349–360

Nakazawa S (1973) Artificial induction of lake balls. Naturwissenschaften 60(10):481. doi:10.1007/BF00592871

Nakazawa S (1974) The time and the cause of extermination of lake balls from Lake Zeller. Bull Jpn Soc Phycol 12(3):101–103

Niiyama Y (1989) Morphology and classification of C. aegagropila in Japanese lakes. Phycologia 28(1):70–76

Noskov GA (2000) Red data book of nature of the Leningrad region, vol. 2. World and Family, St Petersburg

Palik P (1963) Studien über Aegagropila sauteri (Neetz) Kutz. Ann Univ Sci Budapestinensis Sect Biol :179–192

Pankow H (1965) Aegagropila sauteri in Mecklenburg (Norddeutschland). Nova Hedwigia 9:177–184

Pankow H (1985) Verschollene, gefährdete und interessante Großalgen im nördlichen Gebiet der DDR. Bot Rdbr Bez Neubrandenburg 16:65–72

Pankow H, Bolbrinker B (1984) Über die Verbreitung und Soziologie von Cladophora aegagropila (L.) Rbh [=Aegagropila sauteri (Nees ex Kütz.) Kütz.] in den Nordbezirken der DDR. Gleditschia 12(2):279–283

Rambaut A (2007) Se-Al v2.0a11. Available via http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/Accessed 07 May 2008

Riegman R (2004) De waterkwaliteit en de ecologische toestand van de boezem van noordwest Overijssel in de periode 2000–2003. Waterschap Reest en Wieden, Meppel

Sakai Y, Enomoto S (1960) Attaching organ of a species of Aegagropila growing on small stones. Bull Jpn Soc Phycol 8:117–123

Schlichting HE (1960) The role of waterfowl in the dispersal of algae. Trans Am Microsc Soc 79:160–166. doi:10.2307/3224082

Schories D, Härdle W, Kaminski E, Kell V, Kühner E, Pankow H (1996) Rote Liste und Florenliste der marinen Makroalgen (Chlorophyceae, Rhodophyceae et Fucophyceae) Deutschlands. Schr-R Vegetationskde 28:577–607

Segal S, Groenhart MC (1967) Het Zuideindigerwiede, een uniek verlandingsgebied. Gorteria 11(3):165–177

Soejima A, Yamazaki N, Nishino T, Wakana I (2008) Genetic variation and structure of the endangered freshwater benthic alga Marimo, Aegagropila linnaei (Ulvophyceae) in Japanese lakes. Aquat Ecol. doi:10.1007/s10452-008-9204-9

ten Winkel EH, Meulemans JT (1984) Effects of fish upon submerged vegetation. Hydrobiol Bull 18(2):157–158. doi:10.1007/BF02257054

van Berkum JA, Klinge M, Grimm MP (1995) Biomanipulation in the Duinigermeer; first results. Neth J Aquat Ecol 19(1):81–90. doi:10.1007/BF02061791

van den Hoek C (1963) Revision of the European species of Cladophora. EJ Brill, Leiden

Van Liere L, Gulati RD (eds) (1992) Restoration and recovery of shallow eutrophic lake ecosystems in The Netherlands. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Waern M (1952) Rocky-shore algae in the Öregrund Archipelago. Acta Phytogeogr Suec 30:1–298

Wakana I (1993) Marimo: a freshwater alga peculiar to Hokkaido. Nat Life Hokkaido 7:11–19 (in Japanese)

Wakana I, Arai S, Nagao M (1996) A current situation of population and living environment of Cladophora aegagropila in Lake Chimikeppu, Abasiri branch of Hokkaido. Marimo Res 5:1–11 (in Japanese)

Wakana I, Arai S, Sano O, Honoki H (2001) Current situation and living environment of freshwater alga “Tateyama-marimo (Aegagropila sp. nov.)” in the Saryfutsu-Hamatonbetsu lake group, Hokkaido, Japan. J Plant Res 114(suppl):59. doi:10.1007/PL00013968

Wakana I, Tsuji N, Takayama H, Suzuki Y, Watanabe M, Sano O (2005) Current situation and living environment of an endangered algal species Marimo (Aegagropila linnaei) in Takkobu Marsh, Kushiro-Shitsugen Wetland. J Plant Res 118(suppl):64

Wesenberg-Lund C (1903) Sur les Aegagropila sauteri du Lac de Sorö. Académie royale des sciences et des lettres de Danemark extrait du bulletin de l’année 2:167–203

Whitton BA, Boulton PNG, Clegg EM, Gemmell JJ, Graham GG, Gustar R, Moorhouse TP (1998) Long-term changes in macrophytes of British rivers: 1. River Wear. Sci Total Environ 210/211:411–426. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00028-X

Yoshida T, Horiguchi T, Nagao M, Wakana I, Yokohama Y (1994) Photosynthetic and respiratory property of the large size spherical aggregations of ‘Marimo’. Marimo Res 3:1–6

Acknowledgments

We wish to express thanks to the curators of the herbaria who provided access to their collections (Table 1), the collectors of fresh material for DNA analyzes (Table 3), and R. Riegman (Waterschap Reest en Wieden), K. Vendrig (Waternet), E. Nat (Landelijk Informatiecentrum Kranswieren), and M. Thannhauser (Wetterskip Fryslân) for information. A. Bouman (Stichting Natuurmonumenten), K. K. M. Kulju, and P. Feuerpfeil are acknowledged for their assistance with field work. This study was supported in part by the European SYNTHESYS program and the Schure-Beijerinck-Popping-Fund.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Boedeker, C., Immers, A. No more lake balls (Aegagropila linnaei Kützing, Cladophorophyceae, Chlorophyta) in The Netherlands?. Aquat Ecol 43, 891–902 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-009-9231-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-009-9231-1