Abstract

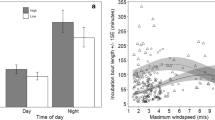

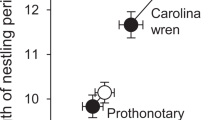

During incubation, tropical passerines have been shown to have lower levels of nest attentiveness than their counterparts at north temperate latitudes, spending a higher percentage of daylight time off the nest. This difference has been interpreted as evidence of parental restraint; tropical birds allocate more time to daily self-maintenance, perhaps preserving their higher annual survival rates and future breeding potential. But such comparisons are susceptible to the confounding effects of day length variation, because a given amount of time spent off the nest will account for a greater percentage of daylight time near to the equator than at high latitudes during spring and summer. Based on a pattern of increasing day length between 0° and 70°N, we show that the impact of this bias is likely to be small where sites are separated by less than 30°–40° of latitude, but should increase substantially both with latitudinal span and distance from the equator. To illustrate this effect, we compared nest attentiveness in two congeners breeding at 1°S and 52°N. During incubation, Stripe-breasted Tits Parus fasciiventer in Uganda had a shorter working day (time from emerging to retiring) than north temperate Great Tits P. major, and spent a higher percentage of daylight time off the nest (32 %) than Great Tits in the UK (24 %). However, this difference was almost wholly explained by the latitudinal difference in day length; the amount of time spent off the nest differed by just 10 min day−1 (<1 % of the 24-h cycle). We show that this effect may be moderated by the change in working day length, which increased less rapidly (in relation to latitude) than day length. Although these effects can thus confound latitudinal comparisons of nest attentiveness, accentuating a pattern predicted by life-history theory, they are avoidable if attentiveness is expressed as the percentage of time or the number of minutes spent incubating per 24 h.

Zusammenfassung

Die von der geographischen Breite abhängigen Veränderungen von Tageslicht- und Arbeitstaglänge verfälschen vergleichende Untersuchungen der Zeiten, die tropische Vögel und solche aus gemäßigten Breiten am Nest verbringen

Für tropische Sperlingsvögel ist gezeigt worden, dass sie während der Brutzeit ihren Nestern weniger Zeit und Aufmerksamkeit als ihre Artgenossen in nördlicheren Breiten schenken und einen größeren Anteil der Tageslichtzeit entfernt vom Nest verbringen. Dieser Unterschied ist als Beweis für elterliche Fürsorge interpretiert worden; tropische Vögel investieren täglich mehr Zeit in die eigene Versorgung und Pflege. So können sie ihre eigene höhere Überlebensrate halten und dadurch einen potentiell größeren Bruterfolg in der Zukunft erreichen. Solche Vergleiche sind jedoch anfällig für den verfälschenden Einfluss der wechselnden Tageslichtlängen, weil eine bestimmte Dauer Abwesenheit vom Nest in Äquatornähe einen größeren Prozentsatz der Tageslichtzeit ausmacht als in höheren Breiten im Frühjahr und im Sommer. Anhand eines Schemas mit wachsenden Tageslichtlängen zwischen Null Grad und 70 Grad nördlicher Breite können wir zeigen, dass der Einfluss dieses verfälschenden Faktors vermutlich eher klein ist, wenn die betreffenden Gebiete weniger als 30–40 Breitengrade voneinander entfernt liegen, aber bei größeren Abständen voneinander sowie vom Äquator beträchtlich ansteigen müsste. Um diesen Effekt aufzuzeigen, verglichen wir die Nestbetreuung von zwei verwandten Arten, die auf 1 Grad Süd, beziehungsweise auf 52 Grad Nord brüten, miteinander. Während der Brutzeit hatten die Schwarzbrustmeisen (Parus fasciiventer) in Uganda einen kürzeren Arbeitstag (Dauer vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen) als die höher im Norden vorkommenden Kohlmeisen (P. major) und verbrachten einen größeren Anteil (32 %) der Tageslichtlänge entfernt vom Nest als Kohlmeisen im U.K. (24 %). Dieser Unterschied konnte jedoch praktisch komplett mit dem von den Breitengraden abhängigen Unterschied in den Tageslichtlängen erklärt werden; die Zeiten, die die Tiere vom Nest abwesend waren, wichen nur um 10 Min. d-1 (< 1 % des 24-Stunden-Zyklus) voneinander ab. Wir zeigen, dass der Effekt möglicherweise von der Länge des Arbeitstags beeinflusst wurde, die weniger stark (im Verhältnis zur geographischen Breite) als die Tageslichtlänge ansteigt. Obwohl diese Effekte eine vergleichende Untersuchung von Nestanwesenheiten in Abhängigkeit von der geographischen Breite verfälschen können, indem sie ein der Life History-Theorie konformes Verhaltensmuster betonen, kann dieser verfälschende Einfluss vermieden werden, wenn die Nestanwesenheiten in Prozenten statt in absoluten Zahlen angegeben werden, oder in „Minuten Bebrütungsdauer pro 24 Stunden“.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Auer SK, Bassar RD, Fontaine JJ, Martin T (2007a) Breeding biology of passerines in a subtropical forest in northwestern Argentina. Condor 109:321–333

Auer SK, Bassar RD, Martin TE (2007b) Biparental incubation in the chestnut-vented tit-babbler Parisoma subcaeruleum: mates devote equal time, but males keep eggs warmer. J Avian Biol 38:278–283

Balat F (1970) Clutch size in the Great Tit, Parus major Linn., in pine forests of southern Moravia. Zool Listy 19:321–331

Bryan SM, Bryant DM (1999) Heating nest-boxes reveals an energetic constraint on incubation behaviour in great tits, Parus major. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:157–162

Busse P, Gotzman J (1962) Konkurencja gniazdowa i legi mieszane u niektórych gatunków dziuplaków. (Summary: nesting competition and mixed clutches among some birds inhabiting the nestboxes). Acta Ornithol 7:1–32

Camfield AF, Martin K (2009) The influence of ambient temperature on horned lark incubation behaviour in an alpine environment. Behaviour 146:1615–1633

Chalfoun AD, Martin TE (2007) Latitudinal variation in avian incubation attentiveness and a test of the food limitation hypothesis. Anim Behav 73:579–585

Conway CJ, Martin TE (2000) Evolution of passerine incubation behavior: influence of food, temperature, and nest predation. Evolution 54(2):670–685

Cox WA, Martin TE (2009) Breeding biology of the Three-striped Warbler in Venezuela: a contrast between tropical and temperate parulids. Wilson J Ornithol 121(4):667–678

Cramp S, Perrins CM (eds) (1993) The birds of the Western Palearctic, vol VII. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cresswell W, McCleery R (2003) How great tits maintain synchronization of their hatch date with food supply in response to long-term variability in temperature. J Anim Ecol 72:356–366

Cresswell W, Holt S, Reid JM, Whitfield DP, Mellanby RJ, Norton D, Waldron S (2004) The energetic costs of egg heating constrain incubation attendance but do not determine daily energy expenditure in the Pectoral Sandpiper. Behav Ecol 15:498–507

de Heij ME, Ubels R, Visser GH, Tinbergen JM (2008) Female great tits Parus major do not increase their daily energy expenditure when incubating enlarged clutches. J Avian Biol 39:121–126

Dunn EK (1976) Laying dates of four species of tits in Wytham Wood, Oxfordshire. Br Birds 69:45–50

Eguchi K (1980) The feeding ecology of the nestling great tit, Parus major minor, in the temperate ever-green broadleaved forest. II. With reference to breeding biology. Res Pop Ecol 22(2):284–300

Fierro-Calderón K, Martin TE (2007) Reproductive biology of the Violet-Chested Hummingbird in Venezuela and comparisons with other tropical and temperate hummingbirds. Condor 109:680–685

Fontaine JJ, Martin TE (2006) Parent birds assess nest predation risk and adjust their reproductive strategies. Ecol Lett 9:429–434

Frederiksen KS, Jensen M, Larsen EH, Larsen VH (1972) Nogle data til belysning af yngletidspunkt og kuldstørrelse hos mejser (Paridae). Dansk Orn For Tidsk 66:73–85

Howell TR, Dawson WR (1954) Nest temperatures and attentiveness in the Anna Hummingbird. Condor 56:93–97

Kirkham CBS, Davis SK (2013) Incubation and nesting behaviour of the Chestnut-collared Longspur. J Ornithol 154:795–801

Kluijver HN (1950) Daily routines of the Great Tit Parus m. major L. Ardea 38:99–135

Kluijver HN (1951) The population ecology of the Great Tit Parus m. major L. Ardea 39:1–135

Lack D (1966) Population studies of birds. Clarendon, Oxford

Likhachev GN (1967) O velichine kladki nekotorykh ptits v tsentre evropeiskoi chasti SSSR. Ornitologiya 8:165–174

Lloyd P, Taylor WA, du Plessis MS, Martin TE (2009) Females increase reproductive investment in response to helper-mediated improvements in allo-feeding, nest survival, nestling provisioning and post-fledging survival in the Karoo Scrub-Robin Cercotrichas coryphaeus. J Avian Biol 40:400–411

Londoňo GA, Levey DJ, Robinson SK (2008) Effects of temperature and food on incubation behavior of the northern mockingbird, Mimus polyglottos. Anim Behav 76:669–677

Lyon BE, Montgomerie RD (1985) Incubation feeding in snow buntings: female manipulation or indirect male parental care? Behav Ecol Sociobiol 17:279–284

Mace R (1989) A comparison of great tits’ (Parus major) use of time in different daylengths at three European sites. J Anim Ecol 58:143–151

Martin TE (2002) A new view of avian life-history evolution tested on an incubation paradox. Proc R Soc Lond B 269:309–316

Martin TE, Ghalambor CK (1999) Males feeding females during incubation. I. Required by microclimate or constrained by nest predation? Am Nat 153(1):131–139

Martin TE, Bassar RD, Bassar SK, Fontaine JJ, Lloyd P, Mathewson HA, Niklison AM, Chalfoun A (2006) Life-history and ecological correlates of geographic variation in egg and clutch mass among passerine species. Evolution 60(2):390–398

Martin TE, Auer SK, Bassar RD, Niklison AM, Lloyd P (2007) Geographic variation in avian incubation periods and parental influences on embryonic temperature. Evolution 61:2558–2569

Matysioková B, Remeš V (2010) Incubation feeding and nest attentiveness in a socially monogamous songbird: role of feather colouration, territory quality and ambient environment. Ethology 116:596–607

Moreau RE (1944) Clutch size: a comparative study, with reference to African birds. Ibis 86:286–347

Orell M, Ojanen M (1983) Timing and length of the breeding season of the Great Tit Parus major and the Willow Tit P. montanus near Oulu, northern Finland. Ardea 71:183–198

Pearse AT, Cavitt JF, Cully JF (2004) Effects of food supplementation on female nest attentiveness and incubation mate feeding in two sympatric wren species. Wilson Bull 116:23–30

Ricklefs RE, Brawn J (2013) Nest attentiveness in several Neotropical suboscine passerine birds with long incubation periods. J Ornithol 154:145–154

Rompré G, Robinson WD (2008) Predation, nest attendance, and long incubation periods of two Neotropical antbirds. Ecotropica 14:81–87

Sanz JJ (1999) Does daylength explain the latitudinal variation in clutch size of Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca? Ibis 141:100–108

Sanz JJ, Tinbergen JM, Rytkonen S (1998) Daily energy expenditure during brood rearing of Great Tits Parus major in northern Finland. Ardea 86:101–107

Sanz JJ, Tinbergen JM, Moreno J, Orell M, Verhulst S (2000) Latitudinal variation in parental energy expenditure during brood rearing in the great tit. Oecologia 122:149–154

Slagsvold T (1976) Annual and geographical variation in the time of breeding of the Great Tit Parus major and the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca in relation to environmental phenology and spring temperature. Ornis Scand 7:127–145

Tieleman BI, Williams JB, Ricklefs RE (2004) Nest attentiveness and egg temperature do not explain the variation in incubation periods in tropical birds. Funct Ecol 18:571–577

Tinbergen JM, Dietz MW (1994) Parental energy expenditure during brood rearing in the Great Tit (Parus major) in relation to body mass, temperature, food availability and clutch size. Funct Ecol 8(5):563–572

Tombre IM, Erikstad KE, Bunes V (2012) State-dependent incubation behaviour in the High Arctic barnacle geese. Polar Biol 35:985–992

Tulp I, Schekkerman H (2006) Time allocation between feeding and incubation in uniparental arctic-breeding shorebirds: energy reserves provide leeway in a tight schedule. J Avian Biol 37:207–218

USNO (2012) US Navy oceanography portal. http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/

van Balen JH (1973) A comparative study of the breeding ecology of the Great Tit Parus major in different habitats. Ardea 61:1–93

van Noordwijk AJ, van Balen JH, Scharloo W (1981) Genetic variation in the timing of reproduction in the Great Tit. Oecologia 49:158–166

Verhulst S, Tinbergen JM (1997) Clutch size and parental effort in the Great Tit. Ardea 85:111–126

von Haartman L (1969) The nesting habits of Finnish birds. I. Passeriformes. Comment Biol 32:1–187

Wilkin TA, King LE, Sheldon BC (2009) Habitat quality, nestling diet, and provisioning behaviour in great tits Parus major. J Avian Biol 40:135–145

Williams GC (1966) Natural selection, the costs of reproduction, and a refinement of Lack’s principle. Am Nat 100:687–690

Zink G (1959) Zeitliche Faktoren im BrutabJauf der Kohlmeise (Parus major). Untersuchungen an einer gekennzeichneten population von Kohlmeisen in Möggingen-Radoifzell (II). Vogelwarte 20:128–134

Acknowledgments

We thank Narsensius Owoyesigire, Savio Ngabirano, Lawrence Tumugabirwe, Margaret Kobusingye and David Ebbutt for assisting with fieldwork, and Alastair McNeilage, Martha Robbins, Miriam van Heist and Douglas Sheil for their hospitality and their support for the Stripe-breasted Tit study at Bwindi. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the British Ornithologists’ Union and the African Bird Club, and the Uganda Wildlife Authority and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology for granting permission for P.S. to participate in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, P., Cresswell, W. Latitudinal variation in day length and working day length has a confounding effect when comparing nest attentiveness in tropical and temperate species. J Ornithol 155, 481–489 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1029-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1029-1