Abstract

Background

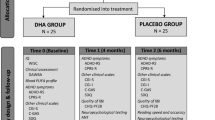

The Micronutrients for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Youth (MADDY) study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a multinutrient formula for children with ADHD and emotional dysregulation. The post-RCT open-label extension (OLE) compared the effect of treatment duration (8 weeks vs 16 weeks) on ADHD symptoms, height velocity, and adverse events (AEs).

Methods

Children aged 6–12 years randomized to multinutrients vs. placebo for 8 weeks (RCT), received an 8–week OLE for a total of 16 weeks. Assessments included the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I), Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5 (CASI-5), Pediatric Adverse Events Rating Scale (PAERS), and anthropometric measures (height and weight).

Results

Of the 126 in the RCT, 103 (81%) continued in the OLE. For those initially assigned to placebo, CGI-I responders increased from 23% in the RCT to 64% in the OLE; those who took multinutrients for 16 weeks increased from 53% (RCT) to 66% responders (OLE). Both groups improved on the CASI-5 composite score and subscales from week 8 to week 16 (all p–values < 0.01). The group taking 16 weeks of multinutrients had marginally greater height growth (2.3 cm) than those with 8 weeks (1.8 cm) (p = 0.07). No difference in AEs between groups was found.

Conclusion

The response rate to multinutrients by blinded clinician ratings at 8 weeks was maintained to 16 weeks; the response rate in the group initially assigned to placebo improved significantly with 8 weeks of multinutrients and almost caught up with 16 weeks. Longer time on multinutrients did not result in greater AEs, confirming an acceptable safety profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity; inquiries may be made to the corresponding author.

References

Johnstone JM et al (2022) Micronutrients for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in youth: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 61(5):647–661

Rucklidge JJ et al (2018) Vitamin-mineral treatment improves aggression and emotional regulation in children with ADHD: a fully blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59(3):232–246

Gordon HA et al (2015) Clinically significant symptom reduction in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treated with micronutrients: an open-label reversal design study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25(10):783–798

Darling KA et al (2019) Mineral-vitamin treatment associated with remission in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and related problems: 1-year naturalistic outcomes of a 10-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 29(9):688–704

Salvat H et al (2022) Nutrient intake, dietary patterns, and anthropometric variables of children with ADHD in comparison to healthy controls: a case-control study. BMC Pediatr 22(1):70

Villagomez A, Ramtekkar U (2014) Iron, magnesium, vitamin D, and zinc deficiencies in children presenting with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children (Basel) 1(3):261–279

Kaplan BJ et al (2015) The emerging field of nutritional mental health inflammation, the microbiome, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. Clin Psychol Sci 3(6):964–980

Bloch MH, Mulqueen J (2014) Nutritional supplements for the treatment of ADHD. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 23(4):883–897

Hariri M, Azadbakht L (2015) Magnesium, iron, and zinc supplementation for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review on the recent literature. Int J Prev Med 6:83

Lange KW et al (2017) The role of nutritional supplements in the treatment of ADHD: what the evidence says. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19(2):8

Rosi E et al (2020) Use of non-pharmacological supplementations in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a critical review. Nutrients 12(6):1573

Leung BMY et al (2022) Paediatric adverse event rating scale: a measure of safety or efficacy? Novel analysis from the MADDY study. Curr Med Res Opin 38(9):1595–1602

Swanson JM et al (2017) Young adult outcomes in the follow-up of the multimodal treatment study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: symptom persistence, source discrepancy, and height suppression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 58(6):663–678

Baweja R, Hale DE, Waxmonsky JG (2021) Impact of CNS stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on growth: epidemiology and approaches to management in children and adolescents. CNS Drugs 35(8):839–859

Waxmonsky JG et al (2020) A randomized controlled trial of interventions for growth suppression in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treated with central nervous system stimulants. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 59(12):1330–1341

Guy W (1985) National Institute of Mental Health. CGI (Clinical Global Impression) scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:839–843

Dunlop BW, Gray J, Rapaport MH (2017) Transdiagnostic clinical global impression scoring for routine clinical settings. Behav Sci (Basel) 7(3):40

Gadow K, Sprafkin J (2015) Child and adolescent symptom inventory-5. Checkmate Plus

March J, Karayal O, Chrisman A (2007) CAPTN: the pediatric adverse event rating scale. In: The Scientific Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Boston

Johnstone JM et al (2019) Rationale and design of an international randomized placebo-controlled trial of a 36-ingredient micronutrient supplement for children with ADHD and irritable mood: the Micronutrients for ADHD in Youth (MADDY) study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 16:100478

Flanagin A et al (2021) Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA 326(7):621–627

Johnstone JM et al (2020) Development of a composite primary outcome score for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and emotional dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 30(3):166–172

StataCorp (2017) Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017, StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX

Berk M et al (2008) The validity of the CGI severity and improvement scales as measures of clinical effectiveness suitable for routine clinical use. J Eval Clin Pract 14(6):979–983

Murray DW et al (2007) Parent versus teacher ratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in the Preschoolers with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Study (PATS). J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17(5):605–620

Roskell NS et al (2014) Systematic evidence synthesis of treatments for ADHD in children and adolescents: indirect treatment comparisons of lisdexamfetamine with methylphenidate and atomoxetine. Curr Med Res Opin 30(8):1673–1685

Willard VW et al (2016) Concordance of parent-, teacher- and self-report ratings on the Conners 3 in adolescent survivors of cancer. Psychol Assess 28(9):1110–1118

Fraser A et al (2018) The presentation of depression symptoms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: comparing child and parent reports. Child Adolesc Ment Health 23(3):243–250

Waxmonsky JG et al (2022) Predictors of changes in height, weight, and body mass index after initiation of central nervous system stimulants in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr 241:115-125.e2

Greenblatt JM, Delane DD (2017) Micronutrient deficiencies in ADHD: a global research consensus. J Orthomol Med. 32(6)

Johnstone JM et al (2020) Multinutrients for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 12(11):3394

Storebø OJ et al (2018) Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents - assessment of adverse events in non-randomised studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5(5):Cd012069

Hennissen L et al (2017) Cardiovascular effects of stimulant and non-stimulant medication for children and adolescents with ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials of methylphenidate, amphetamines and atomoxetine. CNS Drugs 31(3):199–215

Stuckelman ZD et al (2017) Risk of irritability with psychostimulant treatment in children with ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 78(6):e648–e655

Acknowledgements

The MADDY study researchers would like to thank all the parents and children who participated in the study, giving of their time and data to make this study possible.

Funding

The study was funded through private donations to the Nutrition and Mental Health Research Fund, managed by the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care (FEMHC), plus a direct grant from FEMHC, and from the Gratis Foundation. Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) R90AT008924 to the National University for Natural Medicine, NIH-NCCIH T32 AT002688 to Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH, UL1TR000128, UL1TR002369; UL1TR002733 at OHSU and Ohio State University; OHSU’s Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; the Department of Behavioral Health and Psychiatry and the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health as well as the Department of Human Sciences at Ohio State University. In Canada, funding was received through the Nutrition and Mental Health Fund, administered by the Calgary Foundation. Dr. Leung is supported by the Emmy Droog Chair in Complementary and Alternative Healthcare. Micronutrient supplement and matched placebo were donated by Hardy Nutritionals. The study funders/donors had no role in the design, analysis, or reporting of the study.

Author information

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Forest, Lilly, Noven, Shire, Supernus, Roche, and YoungLiving (as well as NIH and Autism Speaks); has consulted with Pfizer, Tris Pharma, and Waypoint; and been on advisory boards for Arbor, Ironshore, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Shire. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The MADDY study was approved by the US Food & Drug Administration under investigational new drug (IND) #127832, Health Canada (Control #207742), the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB) REB #17-0325, Institutional Review Boards at OHSU IRB #16870, and OSU IRB # 2017H0188.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written parental consent and child assent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Leung, B.M.Y., Srikanth, P., Robinette, L. et al. Micronutrients for ADHD in youth (MADDY) study: comparison of results from RCT and open label extension. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02236-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02236-2