Abstract

d-Aspartate is an endogenous free amino acid in the brain, endocrine tissues, and exocrine tissues in mammals, and it plays several physiological roles. In the testis, d-aspartate is detected in elongate spermatids, Leydig cells, and Sertoli cells, and implicated in the synthesis and release of testosterone. In the hippocampus, d-aspartate strongly enhances N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and is involved in learning and memory. The existence of aspartate racemase, a candidate enzyme for d-aspartate production, has been suggested. Recently, mouse glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1-like 1 (Got1l1) has been reported to synthesize substantially d-aspartate from l-aspartate and to be involved in adult neurogenesis. In this study, we investigated the function of Got1l1 in vivo by generating and analyzing Got1l1 knockout (KO) mice. We also examined the enzymatic activity of recombinant Got1l1 in vitro. We found that Got1l1 mRNA is highly expressed in the testis, but it is not detected in the brain and submandibular gland, where d-aspartate is abundant. The d-aspartate contents of wild-type and Got1l1 KO mice were not significantly different in the testis and hippocampus. The recombinant Got1l1 expressed in mammalian cells showed l-aspartate aminotransferase activity, but lacked aspartate racemase activity. These findings suggest that Got1l1 is not the major aspartate racemase and there might be an as yet unknown d-aspartate-synthesizing enzyme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some free d-amino acids exist at high concentrations in several tissues in mammals. d-Aspartate is present in some tissues such as those in the hippocampus, pineal body, and pituitary in the brain, the submandibular gland (SMG), and the testis (Furuchi and Homma 2005; Hashimoto and Oka 1997; Masuda et al. 2003). In the hippocampus, d-aspartate can strongly enhance N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) and rescue age-related deficiency in synaptic plasticity (Errico et al. 2011). In addition, a high level of d-aspartate is related to learning and memory (Topo et al. 2010). d-Aspartate is also involved in the synthesis and release of the luteinizing hormone in the pituitary and melatonin release in the pineal body (D’Aniello et al. 2000; Ishio et al. 1998; Takigawa et al. 1998). In the testis, d-aspartate is detected in elongated spermatids, Leydig cells, and Sertoli cells, involved in the synthesis and release of testosterone (D’Aniello et al. 1996; Sakai et al. 1998).

Although several studies have shown the functions of d-aspartate, the enzyme producing d-aspartate was not identified in mammals. Wolosker et al. (2000) have revealed that d-aspartate is synthesized from l-aspartate in the primary neuronal cultures derived from rat embryos, suggesting the existence of mammalian aspartate racemase in neurons. Kim et al. (Kim et al. 2010) reported that glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1-like 1 (Got1l1) is the mouse aspartate racemase, and Got1l1 is localized in paraventricular nuclei (PVN), supraoptic nuclei (SON), and hippocampal neurons of the adult mouse brain. A recombinant Got1l1 protein is a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme and synthesizes substantial d-aspartate from l-aspartate and only one-fifth as much l-glutamate, with very little d-glutamate in vitro. Depletion of Got1l1 by short-hairpin RNA in newborn neurons of the adult hippocampus induces defects in dendritic development and survival of newborn neurons. However, the function and contribution of Got1l1 as an aspartate racemase has not been clarified in vivo.

In the present study, we generated Got1l1 knockout (KO) mice. We found that Got1l1 mRNA was highly expressed in the testis in wild-type (WT) mice, but was not detected in Got1l1 KO mice. The d-aspartate contents of WT and Got1l1 KO mice were not significantly different in the testis and hippocampus. We also examined the enzymatic activity of the recombinant Got1l1 prepared from Escherichia coli (E. coli) and HEK293T cells. Got1l1 catalyzed no aspartate racemization, but catalyzed the transamination between l-aspartate and α-ketoglutarate and produced small amount of l-glutamate under the conditions examined.

Materials and methods

Generation of Got1l1 KO mice

Animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the University of Toyama (Authorization No. 2012 med-41) and were carried out in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the University of Toyama.

A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone (B6Ng01-118F09) containing mouse Got1l1 was provided by RIKEN BRC through the National Bio-Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The nucleotide sequence of the mouse genome was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Mouse G+T, Annotation Release.103).

For the construction of the Got1l1-targeting vector, the 5′ homology arm of 5.2 kb (−3,648 to +1,533; the nucleotide residues of the mouse BAC clone are numbered in the 5′–3′ direction, beginning with the A of ATG, the initiation site of translation in Got1l1, which refers to position +1, and the preceding residues are indicated by negative numbers) and 3′ homology arm of 6.9 kb (+1,800 to +8,730) from the BAC clone were subcloned into the pDONR P4-P1R and pDONER P2R-P3 vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively, using a counter-selection BAC modification kit (Gene Bridges, Dresden, Germany). The 266-bp DNA fragment (+1,534 to +1,799) containing Got1l1 exon 2 was amplified by PCR and subcloned between two loxP sites of a modified pDONR221 vector containing a phosphoglycerate kinase (pgk) promoter-driven neomycin cassette (pgk-neo) flanked by two FRT sites. These three plasmids were directionally subcloned into pDEST R4-R3 containing the diphtheria toxin gene (MC1-DTA) using LR clonase of a MultiSite Gateway Three-Fragment Vector Construction kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to yield the targeting vector. The targeting vector linearized with NotI was electroporated into the embryonic stem (ES) cell line RENKA (Fukaya et al. 2006) derived from the C57BL/6N strain as previously described (Mishina and Sakimura 2007; Miya et al. 2008). After the selection with G418, the recombinant ES clone (No. 51) was identified by Southern blot analysis using the 5′ outer probe (−4,407 to −3,807) and 3′ outer probe (+8,821 to +9,416) on NsiI-digested genomic DNA, and the Neo probe (Miya et al. 2008) on KpnI-digested genome DNA. To delete exon 2 of Got1l1 flanked by loxP sites, a circular pCre-Pac plasmid (10 μg) expressing Cre recombinase (Taniguchi et al. 1998) was electroporated into the obtained recombinant ES clone.

The obtained ES clone was injected into eight-cell stage embryos from ICR mice. The embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage and transferred to the uterus of pseudopregnant ICR mice. The resulting male chimeric mice were crossed with female C57BL/6 N mice to establish the mutant mouse line.

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot analysis was performed as previously reported (Miya et al. 2008). In brief, total RNA samples were prepared, using TRIsol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), from the brain, testis, SMG, and liver of WT and Got1l1 KO mice, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and blotted on membranes (Hybond N+; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Blotted membranes were hybridized with a 32P-labeled Got1l1 cDNA fragment corresponding to exons 1 and 2 or a β-actin cDNA fragment corresponding to the protein-coding region.

Measurement of amino acid contents in the testis and hippocampus

To decrease the effect of amino acids derived from food on the amino acid content in the testis and brain, each male mouse was fasted for 24 h before sampling. The mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (65 mg/kg body weight, intra-peritoneal), perfused transcardially with PBS (pH 7.4). The testes and hippocampi were removed, weighed, and frozen in liquid N2. These organs were homogenized in 10 vol. (ml/g) of 0.2 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and the debris was removed by centrifugation. TCA was removed by extraction three times, with water-saturated diethyl ether. The amino acid contents were determined by HPLC as previously described (Ito et al. 2008) with a slight modification. When necessary, d-threo-3-hydroxy aspartate (d-THA) was used as an internal standard. Mobile phase A consisted of 9 % acetonitrile in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 6.0), and mobile phase B was 50 % acetonitrile in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 6.0). A linear gradient of the mobile phase B was developed from 0 to 7.5 % between 0 and 10 min, 7.5–17.5 % between 10 and 35 min, and 17.5–30 % between 35 and 60 min.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

The cDNA clones of mouse Got1l1 and human Got1l1 (hGot1l1) were purchased from DNAFORM (clone ID Nos.: 6533656 for Got1l1 and H013075A20 for hGot1l1). To produce the RNA probe, the cDNA fragment of the mouse Got1l1-coding region (No. 62-1276; NCBI Reference Sequence NM_029674.1), was amplified from the above-mentioned cDNA clone and subcloned into the pBluescript II plasmid vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cRNA probes were prepared as described previously (Yamazaki et al. 2010).

Section preparation and fluorescence in situ hybridization were performed as described previously (Kudo et al. 2012). Fluorescence was detected using a Cy3-TSA plus amplification kit (PerkinElmer. Inc. MA, USA). Finally, sections were counterstained with the fluorescent nuclear stain TOTO3 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA).

Construction and expression of GST-fused Got1l1

The mouse and human Got1l1 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pGEX-4T vector (GE Healthcare). The resultant plasmids named pGEX-Got1l1 and pGEX-hGot1l1 expressed Got1l1 with N-terminally glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged fusion proteins. The E. coli BL21 cells (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) transformed with each plasmid were cultivated in an LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 22 °C. The protein was expressed by adding 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at the mid-log phase. The GST fusion protein was purified by affinity chromatography with glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction.

The d-glutamate auxotrophy assay was performed as described previously (Doublet et al. 1992). We used E. coli WM335 cells harboring the empty vector (pGEX-4T), pGEX-Got1l1, pGEX-hGot1l1, or pICT113 expressing d-amino acid aminotransferase. These E. coli. WM335 cell strains were cultivated with or without 0.1 % d-glutamate on LB agarose plates containing ampicillin and 0.1 mM IPTG. The plates were incubated at 22 °C for 3 days and photographed.

Enzymatic activity of recombinant Got1l1

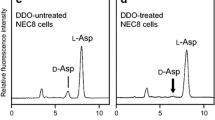

HEK293T cells transfected with an expression vector for C-terminally histidine (His)-tagged Got1l1 (pEB-Got1l1-His) and an empty vector (pEB6) were collected from two Petri dishes (10 cm diameter) each for the preparation of recombinant Got1l1 and control cell extract, respectively. The cells were sonicated in 400 μl of lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 % Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors cocktail lacking EDTA (nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan), and centrifuged at 20,000×g for 30 min. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-Sepharose 6 fast flow resin (GE Healthcare) for 4 h at 4 °C. After the resin was washed five times with wash buffer (PBS containing 10 mM imidazole and 0.5 % Triton X-100), proteins were eluted with 500 μl of elution buffer (PBS containing 1 M imidazole). The eluates were immediately passed through a PD MiniTrap G-25 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with PBS. Then, a 100-μl aliquot of the protein solution was mixed with the same volume of the reaction mixture consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 40 μM PLP, 10 mM l-aspartate, and 10 mM α-ketoglutarate. After 4 h incubation at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated by adding 200 μl of 0.2 M TCA. The formation of d-aspartate, d-glutamate, and l-glutamate was examined by HPLC as described above.

Results

Expression of Got1l1 mRNA in several tissues

To examine the expression of Got1l1 mRNA, we performed Northern blot analysis using total RNA from tissues of the brain, testis, and SMG, because these tissues were reported to contain abundant d-aspartate in mice and rats (Errico et al. 2012; Masuda et al. 2003; Sakai et al. 1998). We detected the main band of about 1.2 kb, in addition to the bands of 0.7 and 2.2 kb in total RNA from the testis (Fig. 1a). These bands corresponding to Got1l1 mRNA were not detected in total RNA from the brain, SMG, and liver.

mRNA expression of Got1l1 in several tissues. a Northern blot analysis of total RNA (10 μg) extracted from the brain (Br), testis (T), submandibular gland (SMG), and liver (Liv) of WT mouse using the Got1l1 exon 1–2 probe. The positions of RNA size markers are indicated on the left side. Br lane is from different part of the same blot. b, c Images of fluorescence in situ hybridization of the testis with (a) or without (b) Got1l1 antisense probe. Red signals of Got1l1 mRNA are detected in spermatocytes and sperms. Some red signals observed in Leydig cells and the lumen of seminiferous tubules without the probe (c) are nonspecific signals. The sections were counterstained with TOTO3 (blue) for nuclear visualization. The bars indicate 100 µm

To examine the distribution of Got1l1 mRNA, we performed in situ hybridization analysis using fluorescence-labeled Got1l1 antisense RNA probe. Specific Got1l1 mRNA signals were detected in primary spermatocytes and sperms in the testis (Fig. 1b, c). We were not able to detect specific Got1l1 mRNA signals in the adult hippocampus and other brain regions (data not shown).

Generation of Got1l1 KO mice

To investigate the function of Got1l1 in vivo, we generated Got1l1 KO mice (Fig. 2a). We constructed a targeting vector in which exon 2 of Got1l1 was flanked by two loxP sequences followed by a pgk-neo selection marker. After the selection using G418, the correctly targeted embryonic stem (ES) cell clone (No. 51) was identified by Southern blot analysis using 5′- and 3′-outer probes (data not shown). To delete the region between the loxP sequences and to generate a frame-shift mutation of a Got1l1 allele (Got1l1 KO), a circular pCre-PAC plasmid (Taniguchi et al. 1998) was transiently introduced into the ES clone. Chimeric mice derived from this ES clone were mated with C57BL/6 N mice to establish the mutant mouse line. After crossing between heterozygous mutant mice, we obtained Got1l1 KO mice identified by Southern blotting (Fig. 2b). The expression of Got1l1 mRNA in the testis was analyzed by Northern blotting. All the bands detected for WT mice showed a decreased intensity for heterozygous mice and were not detectable for the Got1l1 KO mice (Fig. 2c). The Got1l1 KO mice were viable and fertile.

Generation of Got1l1 knockout mouse. a Schematic representation of Got1l1 gene, targeting vector, targeted gene, and Got1l1 KO gene. The coding and noncoding regions of Got1l1 exons are indicated by closed and open boxes, respectively. The inserted pgk-neo gene (Neo) is shown. Met is the initiation site of translation in Got1l1. The restriction enzyme sites (NsiI) and location of probes used (5′ and 3′ probe) are indicated. Black triangles indicate loxP sites. b Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA (8 μg) from WT (+/+) and Got1l1 KO (−/−) mice. NsiI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with the 5′ outer probe (left) and 3′ outer probe (right). The positions of DNA size markers are indicated on the left side. c Northern blot analysis of total RNA (10 μg for Got1l1 probe, 1 μg for Actin probe) extracted from the testes of WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and Got1l1 KO (−/−) mice. The hybridizations were carried out using the Got1l1 exon 1–2 probe (upper) and actin probe (lower). The positions of RNA size markers are indicated on the left side

Comparison of amino acid contents of testis and hippocampus between WT and Got1l1 KO mice

We examined the amino acid contents of the testis in adult WT (n = 4) and Got1l1 KO (n = 4) mice by HPLC. There were no significant differences in d-aspartate content between the two genotypes (Student’s t test, p = 0.21). Furthermore, the contents of other l- and d-amino acids examined were also comparable between the two genotypes (Fig. 3a).

Next, we investigated the amino acid contents of the hippocampus from adult WT (n = 8) and Got1l1 KO (n = 8) mice. Although we did not detect a significant difference in the content of d-aspartate between the two genotypes, we found that the contents of l-glutamate and l-glutamine slightly but significantly decreased in the Got1l1 KO mice (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b).

Aspartate racemase activity of recombinant Got1l1 protein

The above-mentioned findings suggest that Got1l1 is not a major d-aspartate-producing enzyme. We, therefore, attempted to confirm the enzymatic activity of Got1l1. In accordance with a previous report (Kim et al. 2010), we constructed several mouse Got1l1 overexpression vectors using E. coli pET-vector systems, pET15b, and pET22b. Got1l1 was expressed with an N-terminal His tag, with a C-terminal His tag, and without His tag. Unlike in the previous report (Kim et al. 2010), we were unable to obtain Got1l1 as a soluble protein. Various attempts to obtain soluble Got1l1, such as alteration of host cells, coexpression with chaperons, cultivation at low temperatures, or slow induction using a low concentration of an inducer, did not increase the solubility of Got1l1. Similar results were obtained for human Got1l1 (hGot1l1).

We, therefore, changed the expression system from a pET-vector system to a pGEX-vector system, and Got1l1 was expressed as an N-terminally glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged fusion protein in E. coli cells. A small amount of GST-Got1l1 was obtained in a soluble fraction of the E. coli cell lysate when it was expressed at a low temperature (22 °C). We incubated the purified GST-Got1l1 with l-aspartate, but no d-aspartate was formed under the conditions examined (data not shown). Kim et al. (Kim et al. 2010) reported that Got1l1 produces d-glutamate in the presence of l-aspartate and α-ketoglutarate. d-Glutamate production was thus examined using GST-Got1l1 in the presence of l-aspartate and α-ketoglutarate, but no detectable amount of d-glutamate was produced (data not shown). During the reaction, we detected the formation of a small amount of l-glutamate. However, we could not rule out the possibility that l-glutamate was produced by a contaminating transaminase from the E. coli host cells. The enzymatic activity of Got1l1 was also examined using GST-fused hGot1l1 (GST-hGot1l1). However, neither aspartate racemase activity nor d-glutamate-producing activity was observed for GST-hGot1l1 in vitro.

d-Glutamate production using pGEX-Gotl1l and pGEX-hGot1l1 was also examined using E. coli WM335 showing d-glutamate auxotrophy (Doublet et al. 1992). The d-glutamate auxotrophy of E. coli WM335 can be compensated for by expressing of d-amino acid aminotransferase or other enzymes catalyzing the d-glutamate formation although inefficiently (Liu et al. 1998). As shown in Fig. 4, the expression of GST-Got1l1 (and also GST-hGot1l1) did not complement the d-glutamate auxotrophy of E. coli WM335. These findings suggest that GST-Got1l1 catalyzes little or no d-glutamate formation in the E. coli WM335 cells under the conditions used in this study.

d-Glutamate-producing activity of Got1l1 in E. coli WM335 cells. E. coli WM335 cells harboring the empty vector (pGEX-4T) (1), pGEX-Got1l1 (2), pGEX-hGot1l1 (3), or pICT113 expressing d-amino acid aminotransferase (4) were cultivated with (a) or without (b) 0.1 % d-glutamate on an LB plate containing ampicillin and 0.1 mM IPTG at 22 °C for 3 days

We also confirmed the activity of the C-terminally His-tagged Got1l1 expressed in HEK293T cells. The recombinant Got1l1 could be obtained as a soluble protein from HEK293T cells and was batch-purified using a Ni-affinity resin. The presence of Got1l1 was confirmed by western blot analysis using an anti-His-tag antibody. The extract was reacted with l-aspartate, and the resultant reaction mixture was analyzed by HPLC. However, we obtained no detectable amount of d-aspartate. When l-aspartate and α-ketoglutarate were reacted with the Got1l1 purified from HEK293T cells, neither d-aspartate nor d-glutamate was generated, but a detectable amount of l-glutamate was obtained (Fig. 5). When the control cell extract was used instead of Got1l1, l-glutamate was not obtained. These findings strongly suggest that the recombinant Got1l1 has neither aspartate racemase activity nor d-glutamate-producing activity, but has l-aspartate aminotransferase activity in vitro.

Enzymatic activity of recombinant Got1l1. Enzymatic activity of Got1l1 prepared from HEK293T cells was examined. Got1l1 purified from the HEK293T cells harboring an expression vector for Got1l1 (Got1l1), the control cell extract from the cells containing an empty vector (Vector), or PBS (None) was incubated with l-aspartate and α-ketoglutarate for 4 h at 37 °C. The final concentration of Got1l1 in the reaction mixture was approximately 0.5 μg/ml. The reaction was stopped by adding of TCA and the amino acid contents were determined by HPLC. d-THA was added before HPLC as an internal standard

Discussion

In a previous study, Kim et al. (2010) demonstrated that cloned Got1l1 synthesizes substantial d-aspartate, and only one-fifth as much l-glutamate, with very little d-glutamate in vitro. Their results suggest that Got1l1 has aspartate racemase activity, and low aminotransferase activity. However, in this study, we failed to detect Got1l1-catalyzed aspartate racemase activity. Unlike in the previous study, the recombinant Got1l1 was not obtained in a soluble fraction of E. coli when the E. coli pET-vector system was used. GST-fused Got1l1 was obtained as a soluble protein, but it lacked aspartate racemase activity both in vitro and in E.coli. Essentially, the same results were obtained with human Got1l1. The recombinant Got1l1 prepared from HEK293T cells were found to have an l-aspartate aminotransferase activity, but have no aspartate racemase activity in vitro. Although we used relative small amounts of the recombinant Got1l1 protein as compared with previous report (Kim et al. 2010), we detected significant l-aspartate aminotransferase activity. However, we could not detect any d-aspartate racemase activity. Furthermore, we found that there was no significant difference in d-aspartate contents in the testis and hippocampus from WT and Got1l1 KO mice.

We detected a high level of Got1l1 mRNA expression in the testis by Northern blot analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization (Fig. 1). In particular, Got1l1 mRNA was localized in spermatocytes and sperms, but not in spermatogonia and Leydig cells. Got1l1 might be involved in the regulation of spermatogenesis. d-Aspartate was detected in elongate spermatids in the adult rat testis (Sakai et al. 1998). Thus, we examined the contents of some amino acids in the testis of WT and Got1l1 KO mice by HPLC. However, the contents of d-aspartate and other examined amino acids were comparable between the two genotypes (Fig. 3), suggesting that Got1l1 is not a major d-aspartate-producing enzyme in the testis.

The Got1l1 protein is abundantly expressed in the brain and regulates neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus (Kim et al. 2010). In an immunohistochemical analysis, besides Got1l1-immunopositive signals, d-aspartate-immunopositive signals localized in the paraventricular nuclei, supraoptic nuclei, CA3/2 neurons of the hippocampus, and the hilus of the dentate gyrus (Kim et al. 2010). We attempted to produce an anti-Got1l1 antibody using recombinant Got1l1 expressed in E. coli as antigen; however, we were unable to obtain a specific antibody recognizing endogenous Got1l1. Some of the commercially available anti-Got1l1 antibodies could not be used because they detected same signal of bands in brain and testicular homogenate derived from WT and KO mice. Thus, we performed Northern blot analysis using total RNA from the brain, but were not able to detect Got1l1 mRNA (Fig. 1). We were also unable to detect Got1l1 mRNA signals in the adult hippocampus and other brain regions by fluorescence in situ hybridization (data not shown). Our analysis of the content of d-aspartate in the hippocampus of Got1l1 KO mice showed no significant difference from that of WT mice. These findings suggest that expression level of Got1l1 is low and Got1l1 is not a major d-aspartate-producing enzyme in the adult hippocampus. In contrast, the contents of l-glutamate and l-glutamine decreased in the adult hippocampus of Got1l1 KO mice. The reasons underlying the reduced levels of l-glutamate and l-glutamine in the Got1l1 KO hippocampus are currently unknown. One possibility is that Got1l1 expressed in an early developing brain might be involved in amino acid metabolism.

The amino acid sequence of Got1l1 is closely related to those of Got family members, cytosolic Got1 and mitochondrial Got2 (Kim et al. 2010). Both Got1 and Got2 have conserved tryptophan at position 140, which prevents protonation of Cα for racemization of aspartate (Kim et al. 2010). Indeed, chicken-derived Got2 can generate d-aspartate; however, the speed of the reaction is very low; the rate of racemization of aspartate is 3.3 × 10−8 times the rate of transamination (Kochhar and Christen 1992). These findings suggest that members of the Got family are unlikely to be major aspartate racemases.

Recently, a novel dual racemase (DAR1) that can convert aspartate and serine to their chiral form in a PLP-dependent manner has been identified in Aplysia (Wang et al. 2011). DAR1 is 41 % identical to mammalian serine racemase; however, it is only 14 % identical to Got1l1, which did not show any aspartate racemase activity in our study. These findings suggest that the enzymatic pathways are conserved across the metazoan tree of life. One study demonstrated that the levels of d-aspartate in the forebrain are low in the serine racemase KO mice (Horio et al. 2013), which suggests the possibility of the involvement of serine racemase in d-aspartate production. Furthermore, in mammals, there are several poorly characterized serine dehydratase enzymes that show homology with serine racemase. We need to examine the activities of these enzymes and whether they produce d-aspartate in the steps to identify an unknown enzyme producing d-aspartate in mammals.

Abbreviations

- Got1l1:

-

Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase-1 like 1

- KO:

-

Knockout

- WT:

-

Wild type

- ES:

-

Embryonic stem

- SMG:

-

Submandibular gland

- PLP:

-

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- BAC:

-

Bacterial artificial chromosome

- GST:

-

Glutathione S-transferase

References

D’Aniello A, Di Cosmo A, Di Cristo C, Annunziato L, Petrucelli L, Fisher G (1996) Involvement of d-aspartic acid in the synthesis of testosterone in rat testes. Life Sci 59:97–104

D’Aniello A et al (2000) Occurrence of d-aspartic acid and N-methyl-d-aspartic acid in rat neuroendocrine tissues and their role in the modulation of luteinizing hormone and growth hormone release. FASEB J 14:699–714

Doublet P, van Heijenoort J, Mengin-Lecreulx D (1992) Identification of the Escherichia coli murI gene, which is required for the biosynthesis of d-glutamic acid, a specific component of bacterial peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol 174:5772–5779

Errico F et al (2011) Increased d-aspartate brain content rescues hippocampal age-related synaptic plasticity deterioration of mice. Neurobiol Aging 32:2229–2243. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.002

Errico F, Napolitano F, Nistico R, Usiello A (2012) New insights on the role of free d-aspartate in the mammalian brain. Amino Acids 43:1861–1871. doi:10.1007/s00726-012-1356-1

Fukaya M et al (2006) Abundant distribution of TARP gamma-8 in synaptic and extrasynaptic surface of hippocampal neurons and its major role in AMPA receptor expression on spines and dendrites. Eur J Neurosci 24:2177–2190. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05081.x

Furuchi T, Homma H (2005) Free d-aspartate in mammals. Biol Pharm Bull 28:1566–1570

Hashimoto A, Oka T (1997) Free d-aspartate and d-serine in the mammalian brain and periphery. Prog Neurobiol 52:325–353

Horio M, Ishima T, Fujita Y, Inoue R, Mori H, Hashimoto K (2013) Decreased levels of free d-aspartic acid in the forebrain of serine racemase (Srr) knock-out mice. Neurochem Int 62:843–847. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2013.02.015

Ishio S, Yamada H, Hayashi M, Yatsushiro S, Noumi T, Yamaguchi A, Moriyama Y (1998) d-Aspartate modulates melatonin synthesis in rat pinealocytes. Neurosci Lett 249:143–146

Ito T, Hemmi H, Kataoka K, Mukai Y, Yoshimura T (2008) A novel zinc-dependent d-serine dehydratase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J 409:399–406. doi:10.1042/BJ20070642

Kim PM, Duan X, Huang AS, Liu CY, Ming GL, Song H, Snyder SH (2010) Aspartate racemase, generating neuronal d-aspartate, regulates adult neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:3175–3179. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914706107

Kochhar S, Christen P (1992) Mechanism of racemization of amino acids by aspartate aminotransferase. Eur J Biochem 203:563–569

Kudo T et al (2012) Three types of neurochemical projection from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis to the ventral tegmental area in adult mice. J Neurosci 32:18035–18046. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4057-12.2012

Liu L et al (1998) Compensation for d-glutamate auxotrophy of Escherichia coli WM335 by d-amino acid aminotransferase gene and regulation of murI expression. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 62:193–195

Masuda W, Nouso C, Kitamura C, Terashita M, Noguchi T (2003) Free d-aspartic acid in rat salivary glands. Arch Biochem Biophys 420:46–54

Mishina M, Sakimura K (2007) Conditional gene targeting on the pure C57BL/6 genetic background. Neurosci Res 58:105–112. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2007.01.004

Miya K et al (2008) Serine racemase is predominantly localized in neurons in mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 510:641–654. doi:10.1002/cne.21822

Sakai K et al (1998) Localization of d-aspartic acid in elongate spermatids in rat testis. Arch Biochem Biophys 351:96–105. doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.0539

Takigawa Y, Homma H, Lee JA, Fukushima T, Santa T, Iwatsubo T, Imai K (1998) d-Aspartate uptake into cultured rat pinealocytes and the concomitant effect on l-aspartate levels and melatonin secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 248:641–647. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.8971

Taniguchi M, Sanbo M, Watanabe S, Naruse I, Mishina M, Yagi T (1998) Efficient production of Cre-mediated site-directed recombinants through the utilization of the puromycin resistance gene, pac: a transient gene-integration marker for ES cells. Nucleic Acids Res 26:679–680

Topo E, Soricelli A, Di Maio A, D’Aniello E, Di Fiore MM, D’Aniello A (2010) Evidence for the involvement of d-aspartic acid in learning and memory of rat. Amino Acids 38:1561–1569. doi:10.1007/s00726-009-0369-x

Wang L, Ota N, Romanova EV, Sweedler JV (2011) A novel pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent amino acid racemase in the Aplysia californica central nervous system. J Biol Chem 286:13765–13774. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.178228

Wolosker H, D’Aniello A, Snyder SH (2000) d-Aspartate disposition in neuronal and endocrine tissues: ontogeny, biosynthesis and release. Neuroscience 100:183–189

Yamazaki M et al (2010) TARPs gamma-2 and gamma-7 are essential for AMPA receptor expression in the cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci 31:2204–2220. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07254.x

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tomoko Shiroshima for technical assistance. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovation Areas (Comprehensive Brain Science Network) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka-Hayashi, A., Hayashi, S., Inoue, R. et al. Is d-aspartate produced by glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase-1 like 1 (Got1l1): a putative aspartate racemase?. Amino Acids 47, 79–86 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-014-1847-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-014-1847-3