Abstract

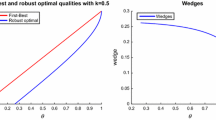

This article analyzes the optimal response of a principal to the regulatory proposal which would truncate agents’ bonus payment in a piece rate tournament at zero. In a model with risk-neutral and heterogenous abilities agents, we analyze the principal’s problem of optimal choice of contract parameters under both regular and truncated tournament scenarios. The results show that the principal could significantly mitigate potential welfare losses due to tournament truncation by adjusting the payment scheme. The optimal adaptation to tournament truncation results in a situation where both higher and lower ability players would benefit from the policy while average ability players would lose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notice that in the exact version of this model (with two margins), the effort becomes vector-valued where one element impacts the feed conversion and the other mortality, which would cause intractable modeling complexity (especially in the truncated case). As far as the analysis of the existing contracts is concerned, the assumption about fixed output is reasonable because the dispersion of individual producers birds’ weight around the average target weight is typically quite narrow which indicates that the effect of effort on the second margin (mortality) has to be quite small (mortality appears to be random) and consequently the incentive effect of b should be muted.

Tsoulouhas and Vukina (1999) have shown that the observed contract can be interpreted as a first-order Taylor series approximation of the optimal rule. Needless to say, adding more realism to the model would bring the observed contract even further away from the optimal scheme.

The main reason for numerous complaints about tournaments as a means of settling production tournaments is the fact that some producers win whereas others loose disproportionate number of contests. Those on the losing side are the most vocal advocates of tournaments regulation or even their outright ban.

Since idiosyncratic shocks \(w_i\) are assumed identical and independently normally distributed with mean 0 and variance \({\sigma _w}^2\), the average idiosyncratic shock \(\bar{w}_{-i}=\frac{\sum _{j\ne i}w_j}{n-1}\) is also normal with mean 0 and variance \({\sigma _w}^2/(n-1)\). The pdf of \(\bar{w}_{-i}\) is \(f_{\bar{w}}(\bar{w}_{-i})=\frac{\sqrt{n-1}}{\sigma _w \sqrt{2\pi }} exp(-\frac{(n-1)\bar{w}_{-i}^2}{2{\sigma _w}^2})\).

Leegomonchai and Vukina (2005) showed that poultry integrators never discriminate by delivering different quality inputs to different abilities contract growers even in production technologies where growers separation based on abilities is theoretically possible.

This assumption is somewhat restrictive because the change in incentives, in addition to influencing effort, could also alter the pool of agents who accept the contract through sorting. This effect was first documented empirically by Lazear (2000) and subsequently in experimental setting, among others, by Dohmen and Falk (2011) who found that change in the compensation schemes has multidimensional sorting effect with respect to ability, risk aversion, relative self-assessment and even gender. The relationship between incentives and sorting in the context of broiler tournaments is investigated by Wang and Vukina (2016).

This idea is empirically verified in Dubois and Vukina (2009).

A potential problem of the first-order approach of solving for the optimal contract is that the solution to the first-order condition is not always the solution to the agent’s maximization problem. The reason is that it is only the necessary condition. In general, there are more efforts that satisfy the first-order condition than those that satisfy the maximization problem since the objective function need not be concave, see Grossman and Hart (1983). However, this is not an issue in this problem since the first-order condition has only one solution which satisfies the second-order condition automatically when we assume a quadratic cost of effort; see also Mirrlees (1976), Shavell (1979), Rogerson (1985) and Macho-Stadler and Perez-Castrillo (2001).

The principal’s ability to extract agents’ rents is the consequence of (i) the modeling assumption that all growers’ bird weights are the same which changed piece rate into fixed salary b and, (ii) the fact that b is not bounded from below. To the extent that the data supports the equal weight assumption, its consequence on the result is trivial. However, imposing an additional constraint, \(b\ge 0\), on the system (15) could fundamentally change the results. The intuition is straightforward: imagine a situation where the optimal contract requires \(b<0\) in order to reach the first-best solution. Whereas having a contractually negative piece-rate is absurd, having a negative base payment is not. In this case \(b<0\) would mean that instead of being paid a salary, an agent would be required to place a bond or pay something like a franchising fee. In this case, the non-negativity constraint makes it no longer possible to reach this solution. In order to induce the agent to accept the contract and to exert high effort, the principal could be forced to leave the agents with some rents.

This result is consistent with the actual contracts that generated our empirical data where the slope of all available contracts is given by \(\beta =1\).

Similarly, in a different model with homogeneous ability agents and normally distributed aggregated production shock (common and idiosyncratic), Marinakis and Tsoulouhas (2012), after imposing truncation (liquidity constraints), could not obtain either a closed form or a numerical solution to the optimal cardinal tournament parameters. Instead, they were able to obtain significant insight using numerical analysis assuming that idiosyncratic and common shocks follow independent uniform distributions in which case the aggregate shock follows a triangular distribution.

The data set is somewhat old but modern broiler contracts are remarkably similar to what they looked like 20 years ago. In fact, the only change to the tournament payment scheme was an increase in base payment to reflect the overall price inflation in the economy.

The market price is a composite price including US Grade A (branded included) and plant grade ice-packed, whole carcass chill-pack product and whole birds without giblets. The twelve cities are: Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and San Francisco. During the two year period covered by the data, chicken prices were reasonably stable with an average of 61 cents per pound. Because these prices are based on dressed (processed) weight, they need to be converted into live weights using industry average processing yields. Processing yields are positively related to size such that for smaller two categories/contracts we used 72.3% yield and for the remaining three categories/contracts we used 74.9% yield, see Vukina (2005).

Another way of comparing the welfare impacts of regulation would be to compare the payoffs under optimal contract with truncation against the optimal contract without truncation. Since the simulated optimal contract parameters without truncation are fairly close to the actual contract parameters observed in the data, the results would not be appreciably different.

References

Agranov M, Tergiman C (2013) Incentives and compensation schemes: an experimental study. Int J Ind Org 31(3):238–247

Bhattacharya S, Guasch JL (1988) Heterogeneity, tournaments, and hierarchies. J Polit Econ 96:867–881

Bull C, Schotter A, Weigelt K (1987) Tournaments and piece rates: an experimental study. J Polit Econ 95(1):1–33

Dohmen T, Falk A (2011) Performance pay and multidimensional sorting: productivity, preferences, and gender. Am Econ Rev 101(April):556–590

Dubois P, Vukina T (2009) Optimal incentives under moral hazard and heterogeneous agents: evidence from production contracts data. Int J Ind Org 27(4):489–500

GIPSA (2010) Proposed rules: implementation of regulations required under title XI of the food, conservation and energy act of 2008; conduct in violation of the act. Fed Reg 75(119):35338–35354

GIPSA (2011) Implementation of regulations required under title XI of the food, conservation and energy act of 2008: suspension of delivery of birds, additional capital investment criteria, breach of contract, and arbitration. Fed Reg 76(237):76874–76890

Green J, Stokey N (1983) A comparison of tournaments and contracts. J Polit Econ 91:349–364

Grossman SJ, Hart OD (1983) An analysis of the principal-agent problem. Econometrica 51(1):7–45

Harris M, Raviv A (1979) Optimal incentive contracts with imperfect information. J Econ Theory 24

Holmstrom B (1979) Moral hazard and observability. Bell J Econ 10(1):74–91

Innes RD (1990) Limited liability and incentive contracting with ex-ante action choices. J Econ Theory 52(1):45–67

Innes RD (1993) Financial contracting under risk neutrality, limited liability and ex ante asymmetric information. Economica, 27–40

Knoeber C (1989) A real game of chicken: contracts, tournaments, and the production of broilers. J Law Econ Org 5(2):271–292

Knoeber C, Thurman W (1994) Testing the theory of tournaments: an empirical analysis of broiler production. J Labor Econ 12(2):155–179

Knoeber C, Thurman W (1995) “Don’t count your chickens..”: risk and risk shifting in the broiler industry. Am J Agric Econ 77(3):486–496

Lazear E (2000) Performance pay and productivity. Am Econ Rev 90:1346–1361

Lazear E, Rosen S (1981) Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. J Polit Econ 89(5):841–864

Leegomonchai P, Vukina T (2005) Dynamic incentives and agent discrimination in broiler production tournaments. J Econ Manag Strategy 14(4):849–877

Levy A, Vukina T (2004) The league composition effect in tournaments with heterogeneous players: an empirical analysis of broiler contracts. J Labor Econ 22(2):353–377

Macho-Stadler I, Perez-Castrillo J (2001) An Introduction to the Economics of Information: Incentives and Contracts, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Marinakis K, Tsoulouhas T (2012) A comparison of cardinal tournaments and piece rate contracts with liquidity constrained agents. J Econ 105(2):161–190

Mirrlees J (1976) The optimal structure of incentives and authority within an organization. Bell J Econ 7(1):105–131

Nalebuff B, Stiglitz J (1983) Prizes and incentives: towards a general theory of compensation and competition. Bell J Econ 14(1):21–43

Rogerson W (1985) The first-order approach to principal-agent problems. Econometrica 53(6):1357–1368

Shavell S (1979) Risk sharing and incentives in the principal and agent relationship. Bell J Econ 10(1):55–73

Shleifer A (1985) A theory of yardstick competition. RAND J Econ 16(3):319–327

Tsoulouhas T, Vukina T (1999) Integrator contracts with many agents and bankruptcy. Am J Agric Econ 81(1):61–74

Tsoulouhas T, Vukina T (2001) Regulating broiler contracts: tournaments versus fixed performance standards. Am J Agric Econ 83(4):1062–1073

Vukina T (2005) Estimating cost and returns for broilers and turkeys. Project report prepared under the cooperative agreement with USDA-ERS, No. 43-3AEK-2-80123, North Carolina State University, Raleigh

Vukina T, Leegomonchai P (2006) Political economy of regulation of broiler contracts. Am J Agric Econ 88(5):1258–1265

Vukina T, Zheng X (2011) Homogenous and heterogenous contestants in piece rate tournaments: theory and empirical analysis. J Bus Econ Stat 29(4):506–517

Wang Z, Vukina T (2016) Sorting into contests: evidence from production contracts. Dept. of Agricultural and Resource Economics working paper, North Carolina State University, Raleigh

Wu S, Roe B (2005) Behavioral and welfare effects of tournaments and fixed performance contracts: some experimental evidence. Am J Agric Econ 87(February):130–146

Zheng X, Vukina T (2007) Efficiency gains from organizational innovation: comparing ordinal and cardinal tournament games in broiler contracts. Int J Ind Org 25(4):843–859

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project, Accession Number 226630. We would like to thank Xiaoyong Zheng, Atsushi Inoue, Walter Thurman, participants of Southern Economic Association 83rd Annual Meeting in Tampa, FL and participants of Agricultural and Resource Economics Seminar at North Carolina State University for their helpful comments and useful suggestions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Vukina, T. Welfare effects of payment truncation in piece rate tournaments. J Econ 120, 219–249 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-016-0516-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-016-0516-2