Abstract

This study outlines trends in quality of delivered non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) care in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2011 and to what extend this was influenced by the national Visible Care program, which aimed at increasing transparency by providing insight into the quality of healthcare. We analyzed data collected from medical records in two observational studies, combined into 20 validated quality indicators (QIs) of which 6 were included in the national program. A random sample of 771 patients, diagnosed with NHL in 26 Dutch hospitals, was examined. Multilevel regression analyses were used to assess differences in quality of NHL care and to provide insight into the effect of the national program. We reported improved adherence to only 3 out of 6 QIs involved in the national program and none of the other 14 validated QIs. Improvement was shown for performance of all recommended staging techniques (from 26 to 43 %), assessment of International Prognostic Index (from 21 to 43 %), and multidisciplinary discussion of patients (from 23 to 41 %). We found limited improvement in quality of NHL care between 2007 and 2011; improvement potential (<80 % adherence) was still present for 13 QIs. The national program seems to have a small positive effect, but has not influenced all 20 indicators which represent the most important, measurable parts in quality of NHL care. These results illustrate the need for tailored implementation and quality improvement initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) affects over 300,000 people worldwide each year [1]. NHL is listed in the top 10 of most common cancers, with an estimated number of 69,000 new cases in the USA in 2013 [2] and responsible for 3 % of all cancer deaths in the USA [3]. In the Netherlands, the incidence of NHL is as high as 4000 newly diagnosed patients per year. With an expanding and ageing population, these figures are expected to increase. Well-organized and well-carried-out diagnostics and treatments are essential to help patients in the best possible way. Treatment of NHL is highly dependent on the subtype, stage, and aggressiveness of the tumor. For the most common subtypes, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL), chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy (i.e., monoclonal antibody rituximab) has improved patient outcomes remarkably [4, 5]. Despite these improvements, the 5-year relative survival rate for these patients is only 50–75 % [6].

To deliver high-quality care to patients diagnosed with NHL, multidisciplinary evidence-based guidelines are developed to help professionals in their choices about diagnostics and therapy [7–10]. Quality of care can be measured using quality indicators, which are “measurable elements of practice performance for which there is evidence or consensus that they can be used to assess the quality of care” [11]. From previous research, it is known that discrepancies exist between NHL care delivered in daily practice and the (quality of) care recommended in guidelines [12–14]. Gaining insight into quality of delivered care is an upcoming phenomenon in healthcare; hospitals and other healthcare facilities are exposed to (external) auditing and benchmarking, often using quality indicators [15–17]. Especially healthcare insurances, policy makers (government) and patient organizations are important actors. The USA and UK have both introduced public reporting as a tool to improve the quality of care. National institutes as the National Quality Forum and the Dr Foster Health focus on delivering healthcare information to the public, for example, by providing a hospital guide to the public including information on waiting times, length of stay, and mortality rates for several surgical procedures [18].

In the Netherlands, a national initiative of transparency in hospital care started in 2008, raised and funded by the government (Visible Care program). The aim of this initiative was to increase transparency by providing insight into the quality of healthcare and enabling healthcare providers to report on actually applied diagnostics and delivered therapy and follow-up. Quality indicators were developed and measured for over 100 disease entities, including malignant lymphoma.

This study outlines the differences in quality of delivered NHL care in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2011 and to what extend this was influenced by the Visible Care program.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

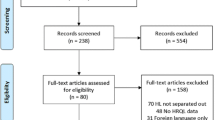

Data from two observational studies were used to investigate the natural course of delivered quality of NHL care and the influence of the Visible Care program. First, Wennekes et al. developed quality indicators and measured their performance in 22 Dutch hospitals by including 348 patients diagnosed with NHL between 2006 and 2007 [14]. The quality indicators were derived from evidence-based guidelines and developed by an expert panel using the systematic RAND-modified Delphi method [19]. The main goal was to provide insight into guideline adherence for the most important processes and structures of NHL care. Second, baseline measurements of the Perineal Assessment and Repair Longitudinal (PEARL) study [20], a cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT), also assessed indicator performance in 19 Dutch hospitals and randomly included 423 patients diagnosed with NHL between 2010 and 2011. Patients eligible for both studies were defined as patients diagnosed with a mature B-, T-, or NK-cell neoplasm and older than 18 years at diagnosis. Patients with multiple myeloma or cutaneous lymphoma or presenting with chronic leukemia were excluded.

Data collection

For the PEARL study, trained registration employees collected data from medical records for the quality indicators. A digital registration form was accomplished in collaboration with the Comprehensive Cancer Centre the Netherlands (CCC). Selection of patients took place using the cancer registry, which is part of the CCC. The CCC used the cancer registry to make a list of potentially eligible patients in the participating hospitals. Patients were randomly listed, after which the first 30 patients were selected and data was collected for 20–25 patients per hospital. This cancer registry is based on the pathology coding system of the World Health Organization (WHO), and patients with mature B-, T-, and NK-cell neoplasms were selected for inclusion.

Patient characteristics (gender, age, hospital region, patient preferences, comorbidities) and tumor-specific information (morphology, stage, extra nodal disease, previous malignancies, and lactate dehydrogenase (LD) values) were collected. Furthermore, dates and data about diagnosis (pathology, imaging techniques, blood counts), treatment of NHL (type of therapy, response), and multidisciplinary consultation were assessed. This information was used to determine the indicator performance scores: the percentage of patients who received care as recommended in the guidelines. If the indicator scores where <90 %, improvement potential was considered to be present [21, 22]. Quality indicators for the domain diagnosis and staging, treatment and follow-up, and organization and coordination were included in the indicator set (see Table 2). The data collection method for the PEARL study (2011 dataset) is in line with the method described by Wennekes et al. [14] (2007 dataset).

The national transparency initiative

In the context of the Visible Care program, a national transparency initiative to provide insight into the quality of hospital care, quality indicators for malignant lymphoma were developed in 2010 [23]. The purpose was to develop quality indicators which represent the most important parts of NHL care and could be easily measured by the hospitals themselves. All disciplines involved in NHL care were asked to provide delegates to participate in the development of the indicator set. The final indicator set included indicators about Ann Arbor staging and International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring, performing all required staging techniques such as bone marrow biopsy and CT scans, assessing therapy response, arranging multidisciplinary consultations, and providing all diagnostic results within 4 weeks. The indicator set as developed by Wennekes et al. [14] was used as one of the references during the development of this Visible Care indicator set. The implementation of the quality indicators was mandatory, since the program was part of new national policy. Each year, hospitals were asked to provide the malignant lymphoma indicator results about the previous year. Yearly feedback was given to the hospitals by providing anonymous results of all hospitals outlined by the hospitals’ own results. All anonymous results were made publically available through the website www.zichtbarezorg.nl, with the intention that these feedback methods would lead to higher quality of overall NHL care. It was the hospitals’ own responsibility in which way the yearly audit was performed and the feedback was processed.

Wennekes et al. [14] collected data of hospital care before the introduction of the Visible Care program, and we repeated this assessment after the first 2 years of the program. In this way, it was possible to provide insight into the proposed positive effect of the national transparency initiative on the quality of delivered medical care.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to get insight into the patient characteristics of the two study populations. Quality indicator scores were assessed for both datasets (2007 and 2011) and expressed in percentages to describe current practice. Univariate analyses (Χ 2 tests) were used to test whether differences in patient characteristics and quality indicator scores were present between 2007 and 2011.

The relation between patient and tumor characteristics (e.g., gender, previous malignancies, and LD value) and differences in quality indicator scores between 2007 and 2011 was studied using univariate logistic regression analyses (P < 0.05). Factors often mentioned as reasons for non-adherence were also included: Charlson index, performance status, Ann Arbor stage, patient preferences, and type of lymphoma. Clinical relevant determinants that influenced quality indicator scores in a univariate setting were tested as a group using multivariate, multilevel logistic regression analyses (odds ratios). In case of intercorrelations between characteristics (>0.4), only one of the two was included in multivariate analyses. A multilevel model was used to account for the nested structure of the data, with individual patients nested within hospitals. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each quality indicator to get insight into the cluster effect of the hospitals. ICC values between 0 and 0.40 are found in other secondary care research [24].

Reliability of the data collection was assessed with a duplicate registration of 30 records by two registration employees in three hospitals. The reliability of the indicator scores was calculated with a Kappa value, a statistical measure for interobserver agreement corrected for chance [25]. A missing values analysis (t test) was performed to explore if more than 5 % of the data was missing and if missing values were missing completely at random (Little’s test).

All statistical analyses, except multilevel analyses, were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IMB Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Multilevel analyses were performed using SAS software system for Windows, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 348 patients of the 2007 dataset and 423 patients of the 2011 dataset. There were no significant differences in gender, age, prevalence of NHL subtypes, aggressiveness of the tumor, Charlson index, patient preferences, and hospital region between the two study populations. In 2011, more patients were included with previous malignancies, Ann Arbor stages III–IV, and normal LD values, compared to 2007.

Quality indicator scores

Table 2 describes the 20 quality indicator scores, corrected for case-mix (i.e., gender, Ann Arbor stage, aggressiveness, previous malignancies, LD value, Charlson index, and hospital region) and the nested structure of the data (multilevel analysis). The quality indicators were divided into three domains: diagnosis and staging, treatment and follow-up, and organization and coordination of care.

Diagnosis and staging

In this domain, improvement is seen for two of the seven quality indicators. Indicator scores for execution of all recommended staging techniques (QI4) improved from 26 to 43 % (OR = 1.902 (1.268–2.852)), and assessment of the International Prognostic Index (QI5) improved from 21 to 43 % (OR = 2.883 (1.675–4.961)). Two indicators scored significantly lower in 2011 compared to 2007: diagnosis based on morphology and immune phenotype decreased from 99 to 96 % (QI3: OR = 0.190 (0.049–0.744)) and examination of blood counts decreased from 90 to 82 % (QI7: OR = 0.576 (0.340–0.976)).

Treatment and follow-up

No significant differences are seen for the six quality indicators in this domain.

Organization and coordination of care

In this domain, only one of the seven quality indicator scores significantly improved (QI17): more patients (41 %) were discussed in multidisciplinary consultations in 2011 compared to 2007 (23 %) (OR = 3.360 (2.007–5.624)).

Influence of the national transparency initiative

The six quality indicators used as initial concept for the Visible Care quality indicators are underlined in Table 2. Significantly increased quality indicator scores were found for three of the six indicators incorporated in the transparency initiative: the use of all staging techniques increased from 26 to 43 %, the assessment of the IPI from 21 to 43 %, and patients discussed in multidisciplinary consultations from 23 to 41 % (QI4, QI5, and QI17, respectively).

The other three quality indicators included in the transparency initiative did not change significantly: 80 % of the patients was staged according to the Ann Arbor classification (QI2), 60 % had a correct evaluation after chemotherapy (QI11), and the maximum diagnostic period of 4 weeks was realized in about half of the patients (QI19). Two of the 14 quality indicators that were not included in the Visible Care program showed significantly decreased scores (QI3 and QI7).

Statistics

The mean ICC was 0.14 (range 0.005–0.33), which was calculated for all quality indicators to account for clustering. The reproducibility of the data collected for the indicator scores in 2011 was good: the average kappa value was 0.8 (range 0.4–1.0; 87 % ≥0.6). This indicates an overall good agreement between the registration employees. For the 2007 dataset, reproducibility was also good [14]. Missing value analysis showed overall less than 5 % missing data in the overall dataset (2007 and 2011). The factor “performance status” was excluded from analysis because it was missing for most of the cases (80 %). Quality indicator 13 had 10 % missing values; however, these were missing completely at random (MCAR, P = 0.771).

Discussion

In this study, we provided insight into the differences in quality of delivered NHL care in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2011, taking into account the Visible Care program. The data indicated that quality of delivered NHL care improved at a few points, but also showed a greater need for improvement for several quality indicators. Indicator scores that decreased significantly included assessment of immune phenotype for diagnosis and full examination of blood counts. However, significant improvement was shown for execution of all recommended staging techniques, assessment of the IPI, and multidisciplinary discussion of patients.

Quality indicators included in the Visible Care program concerning malignant lymphoma were developed and published in 2010. The main goal of this program was to increase transparency of the Dutch hospital care, for which publically available data were required. This could have been a major incentive for hospitals to meet the quality indicators and thus improve their NHL care (if necessary). It is noticeable that the quality indicators with increased scores (QI4, QI5, and QI17) between 2007 and 2011 were all included in the national initiative, which implies a positive effect of the program. However, other (local) initiatives or international study results were not taken into account in our analysis. For example, the added value of discussing all oncology patients during multidisciplinary consultations has been an increasing point of interest the past years, which could have influenced our results.

Quality indicator scores that significantly decreased between the two measurements included items about pathology diagnosis based on immune phenotype (QI3) and examination of leukocyte differentiation during blood analyses (QI7). Despite these decreases, the scores were still between 80 and 100 %, which indicates good performance and only a small improvement potential. Improvement potential is often assigned to indicator scores below 90 % [21, 22], since higher scores might not be feasible due to case-mix factors as high age, many comorbidities, and patient preferences. It can therefore be argued if the significantly decreased scores seen for the two quality indicators are clinically relevant.

Between 2007 and 2011, there were no large changes in guideline recommendations for NHL care in the Netherlands, besides the addition of a recommendation to use fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans for determining therapy response [26, 27]. Using CT scanning, location and size in millimeters should be documented, which is not necessary when a FDG-PET scan is done, since it is based on color intensity instead of size. This could possibly explain the decreasing trend observed in the quality indicator concerning lesions documented in radiology reports after therapy (QI10 67 to 58 %, not significant). Based on our datasets, we determined that FDG-PET (CT-)scans were used more often for evaluation after chemotherapy in 2011 (63 %) compared to 2007 (29 %, P < 0.001).

Another decreasing trend was seen providing all diagnostic results within 4 weeks after the first visit to the hospital (QI19 56 to 49 %, not significant). A factor that may play a role is referral of patients between and within hospitals, which increased from 51 % in 2007 to 64 % in 2011 (P < 0.001). A possible explanation for this might be the increasing burden on the healthcare system, caused by the growing needs of patients. Although this decreasing trend is not significant, and therefore subject to chance, providing all diagnostic results within 4 weeks might be worth arguing because of its clinical importance concerning prognosis and start of treatment for patients diagnosed with NHL. We believe that longer waiting times could result into poorer prognosis for patients, which is already known for patients with head and neck cancer [28]. Furthermore, short waiting times are valuable for the level of patient centeredness of hospitals, of which the importance has grown considerably.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that focused on providing insight into the differences in time in quality of delivered NHL care and evaluated the effect of a national transparency initiative. Besides the present study and Wennekes et al.’s [14], only a few other studies conducted research on quality of NHL care, focusing on parts of the care process such as staging and treatment [12, 13, 29], or follow-up care [30]. In line with our study, they showed that the quality of NHL care is not yet optimal, compared to the recommended care as described in evidence-based guidelines.

Much research has been conducted concerning public reporting, with widely varying results. However, the effect of performance data on improvement of quality of care is less often studied, and if so, mostly focuses on mortality rates [31]. A study by Lamb et al. [32] explored the 5-year impact of voluntary public reporting on physician groups and showed improvement for ambulatory care measures. Our results are in accordance with these studies; however, we were able to provide insight into the quality of care for several measures not included in the public reporting as well. This provided the unique opportunity to examine the effect of public reporting, as done within the Visible Care program, on total quality of NHL care.

Data collection for observational studies included was performed by independent, trained registration employees. In daily practice or public reporting programs, professionals themselves are often responsible for the data collection, which might introduce bias as they are involved as stakeholders. Our data collection showed also high reproducibility between the registration employees, indicating good competency and reliable data collection.

There are also some limitations to this study. Firstly, the hospitals included for data collection in 2011 are not completely identical to those included in 2007: 15 hospitals participated in both measurements, 11 hospitals either in 2007 or 2011. However, no distinct differences were found in indicator scores when the non-overlapping hospitals were left out of the analyses. Together with a relatively large study population (N = 771), we believe that both datasets are representative for hospitals in the Netherlands.

Secondly, we did not have insight into possible local improvement initiatives of the participating hospitals between 2007 and 2011, which makes it difficult to link the Visible Care program as direct and only attribute to the changes seen in some quality indicators of NHL care. One influencing factor could be that high room for improvement rates were seen for four of the six quality indicators included in this program (<30 % scores, 2007 dataset). It can be argued that, in general, quality indicators with low scores are easier to improve than those with higher scores. Hospitals, participated in the 2007 study, received general feedback on their performance as a group and as hospital region, which might have triggered some local improvement initiatives. However, improving NHL care was not the aim of the 2007 study, and no concrete improvement initiatives are known based on the provided feedback. This result is supported by a Cochrane review, which showed that the effect of audit and feedback on improvement is usually small [33].

In summary, during the 4-year period between 2007 and 2011, we found little improvement in overall quality of NHL care. Improvement potential as found in 2007 remained for all quality indicators in 2011, unless some significant increased indicator scores. Based on our results, we can conclude that a national initiative as the Visible Care program might not have enough power to improve hospital care for NHL in general, but might provide a first step towards a more improvement-oriented hospital care. Improvement strategies tailored to the suboptimal quality of NHL care might be a rational step to develop and test in a randomized setting.

References

Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D (2012) Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 13(8):790–801. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70211-5

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63(1):11–30. doi:10.3322/caac.21166

NCI (2014) SEER cancer statistics. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html#survival. Accessed 17 June 2014

Dotan E, Aggarwal C, Smith MR (2010) Impact of rituximab (Rituxan) on the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. P T 35(3):148–157

Lindenmeyer LP, Hegele V, Caregnato JP, Wust D, Grazziotin L, Stoll P (2013) Follow-up of patients receiving rituximab for diffuse large B cell lymphoma: an overview of systematic reviews. Ann Hematol. doi:10.1007/s00277-013-1811-4

Clarke C, O'Malley C (2007) Chapter 28: non-Hodgkin lymphoma. SEER survival monograph: cancer survival among adults: U.S. SEER program, 1988-2001, patient and tumor characteristics., vol Pub.No. 07-6215. National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda

ACN (2005) Australian Cancer Network diagnosis and management of lymphoma guidelines working party: the Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network: clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphoma in 2005. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/cp107/cp107.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2012

Hovon (2011) Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma protocols. http://www.hovon.nl/werkgroepen/studiewerkgroepen/lymfomen.html. Accessed 4 Dec 2012

Tilly H, Vitolo U, Walewski J, da Silva MG, Shpilberg O, Andre M, Pfreundschuh M, Dreyling M, Group EGW (2012) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 23(Suppl 7):vii78–vii82. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds273

Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Wierda WG, Abramson JS, Advani RH, Andreadis CB, Bartlett N, Bellam N, Byrd JC, Czuczman MS, Fayad LE, Fisher RI, Glenn MJ, Harris NL, Hoppe RT, Horwitz SM, Kelsey CR, Kim YH, Krivacic S, LaCasce AS, Nademanee A, Porcu P, Press O, Rabinovitch R, Reddy N, Reid E, Sokol L, Swinnen LJ, Tsien C, Vose JM, Yahalom J, Zafar N, Dwyer M, Sundar H (2014) Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, Version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw: JNCCN 12(6):916–946

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN (2003) Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ 326(7393):816–819. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816

Berrios-Rivera JP, Fang S, Cabanillas ME, Cabanillas F, Lu H, Du XL (2007) Variations in chemotherapy and radiation therapy in a large nationwide and community-based cohort of elderly patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Clin Oncol 30(2):163–171. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000251356.63237.4f

Friedberg JW, Taylor MD, Cerhan JR, Flowers CR, Dillon H, Farber CM, Rogers ES, Hainsworth JD, Wong EK, Vose JM, Zelenetz AD, Link BK (2009) Follicular lymphoma in the United States: first report of the national LymphoCare study. J Clin Oncol 27(8):1202–1208. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.18.1495

Wennekes L, Ottevanger PB, Raemaekers JM, Schouten HC, de Kok MW, Punt CJ, Grol RP, Wollersheim HC, Hermens RP (2011) Development and measurement of guideline-based indicators for patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 29(11):1436–1444. doi:10.1200/jco.2010.30.1622

Coombs T, Walter G, Brann P (2011) Overview of the national mental health benchmarking project. Australas Psychiatry 19(1):37–44. doi:10.3109/10398562.2010.539221

NHSScotland (2007) National benchmarking project—the NHSScotland benchmarking approach. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/174619/0048921.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2014

van der Geest LG, Krijnen P, Wouters MW, Erkelens WG, Marinelli AW, Nortier HJ, Tollenaar RA, Struikmans H, Comprehensive Cancer Centre the Netherlands LL (2012) Improved guideline compliance after a 3-year audit of multidisciplinary colorectal cancer care in the western part of the Netherlands. J Surg Oncol 106(1):1–9. doi:10.1002/jso.23038

Foster D (2013) Essential reading for smart spending: dr Foster hospital guide 2013

Campbell SM, Cantrill JA, Roberts D (2000) Prescribing indicators for UK general practice: Delphi consultation study. BMJ 321(7258):425–428

Stienen JJ, Hermens RP, Wennekes L, van de Schans SA, Dekker HM, Blijlevens NM, van der Maazen RW, Adang EM, van Krieken JH, Ottevanger PB (2013) Improvement of hospital care for patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial (PEARL study). Implementation Science: IS 8:77. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-77

Mourad SM, Nelen WL, Hermens RP, Bancsi LF, Braat DD, Zielhuis GA, Grol RP, Kremer JA (2008) Variation in subfertility care measured by guideline-based performance indicators. Hum Reprod 23(11):2493–2500. doi:10.1093/humrep/den281

Ouwens MM, Marres HA, Hermens RR, Hulscher MM, van den Hoogen FJ, Grol RP, Wollersheim HC (2007) Quality of integrated care for patients with head and neck cancer: development and measurement of clinical indicators. Head Neck 29(4):378–386. doi:10.1002/hed.20532

Kwaliteitsinstituut Visible Care program. https://www.nvz-ziekenhuizen.nl/onderwerpen/zichtbare-zorg. Accessed 20 June 2014

Campbell MK, Fayers PM, Grimshaw JM (2005) Determinants of the intracluster correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials: the case of implementation research. Clin Trials 2(2):99–107

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Fisher RI, Hagenbeek A, Zucca E, Rosen ST, Stroobants S, Lister TA, Hoppe RT, Dreyling M, Tobinai K, Vose JM, Connors JM, Federico M, Diehl V, International Harmonization Project on L (2007) Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 25(5):579–586. doi:10.1200/jco.2006.09.2403

Hovon Information PET scan. http://www.webcitation.org/6OBgnqlMh. Accessed 19 Mar 2014

Jensen AR, Nellemann HM, Overgaard J (2007) Tumor progression in waiting time for radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol 84(1):5–10. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.001

Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, Bozeman SR, Krasnow SH, Shulman LN, Brown JR, Earle CC, Oh WK, Rabin M, McNeil BJ (2011) Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 154(11):727–736. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00004

Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Alfano CM, Weaver KE, Hamilton AS, Aziz N, Rowland JH (2014) Role of oncologists and primary care physicians in providing follow-up care to non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors within 5 years of diagnosis: a population-based study. Support Care Cancer 22(6):1509–1517. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2113-z

Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG (2008) Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med 148(2):111–123

Lamb GC, Smith MA, Weeks WB, Queram C (2013) Publicly reported quality-of-care measures influenced Wisconsin physician groups to improve performance. Health Aff 32(3):536–543. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1275

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O'Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD (2012) Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6, CD000259. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Frederike Brouwer with the data collection and Reinier Akkermans and Janine Liefers with the statistical analyses is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank the 26 Dutch hospitals (including the PEARL study group) for participating in the observational studies, which made this study possible. Also, many thanks to the CCC and the registration employees who participated in this study. This project was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), grant no. 171103002, The Hague.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

RH and PO had the basic idea for this study, and RH, PO, and JS were responsible for the research question. NB, JvK, and LW commented on the design of the study, and all authors were involved in recruiting hospitals for participation. JS wrote the first draft of this manuscript and was responsible for the revisions. All authors critically reviewed the drafts and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of the PEARL study group (imProvement of patiEnts hospitAl caRe for non-hodgkin’s Lymphoma) are the following: M. Berends, Maasziekenhuis Pantein, Boxmeer; E.C. Dompeling, Isala, Zwolle; Z. Erjavec, Ommelander Ziekenhuis Groep, Delfzijl; K.S. Jie, Atrium Medisch Centrum, Heerlen; P. Joosten, Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden; H. van Kamp, Ziekenhuis Nij Smellinghe, Drachten; R. Komdeur, Martini Ziekenhuis, Groningen; A. Koster, VieCuri Medisch Centrum, Venlo; C. Lensen, Ziekenhuis Bernhoven, Uden; C.M. Mandigers, Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen; V. Mattijssen, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis, Arnhem; M. van de Poel, Laurentius Ziekenhuis, Roermond; J.F. Pruijt, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch; B.P. van Rees, Ziekenhuis Tjongerschans, Heerenveen; M. Smeets, Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix, Winterswijk; W. Stevens, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; J. Swart, Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Assen; Y. Tromp, Röpke Zweers Ziekenhuis, Hardenberg; and F. de Vries, Slingeland Ziekenhuis, Doetinchem.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stienen, J.J.C., Ottevanger, P.B., Wennekes, L. et al. Trends in quality of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma care: is it getting better?. Ann Hematol 94, 1195–1203 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-015-2340-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-015-2340-0