Abstract

Background

Cranial ultrasound is an essential screening and diagnostic tool in the care of neonates and is especially useful in the premature population for evaluation of potential germinal matrix/intraventricular hemorrhage (GM/IVH). There are typically two screening examinations, with the initial cranial sonography performed between 3 days and 14 days after birth, usually consisting of a series of static images plus several cinegraphic sweeps.

Objective

Our primary goal was to assess whether cinegraphic sweeps alone are as accurate for diagnosing neurological abnormalities as combined static and cinegraphic imaging in the initial cranial US evaluation of premature infants. Our secondary goal was to establish the difference in time required to perform these two examinations.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively obtained 140 consecutive initial cranial US screening studies of premature infants. Three pediatric radiologists blinded to patient data read cinegraphic images alone and also combined (dual) imaging sets for a subset of subjects, recording findings for seven disease processes: germinal matrix/intraventricular hemorrhage (GM/IVH), right or left side; periventricular leukomalacia (PVL); choroid plexus cyst; subependymal cyst; cerebral and cerebellar infarction or hemorrhage; posterior fossa hemorrhage or infarction, and extra-axial hemorrhage. Separately, we compared retrospective dual imaging acquisition time against prospectively collected cinegraphic imaging time for premature infants undergoing initial cranial US evaluation.

Results

Equivalence testing demonstrated no difference in equivalency between initial cranial US screening using cinegraphic evaluation alone and dual imaging for GM/IVH, cerebral and cerebellar infarct or hemorrhage, and subependymal cyst (all P < 0.05). For PVL and choroid plexus cyst, cinegraphic imaging and dual imaging did not demonstrate equivalence (P > 0.05). Cinegraphic images were obtained in less than one-third of the time required for dual imaging.

Conclusion

For the diagnoses that are critical to establish at initial screening (GM/IVH, cerebral and cerebellar infarct or hemorrhage) initial cranial US screening using cinegraphic sweeps was equivalent to dual imaging. Cinegraphic imaging required significantly less time to perform than dual imaging. We suggest that performance of cranial US screening using cinegraphic imaging alone is a potentially advantageous option in the initial evaluation of the premature neonate.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Correa F, Enriquez G, Rossello J et al (2004) Posterior fontanelle sonography: an acoustic window into the neonatal brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25:1274–1282

Pishva N, Parsa G, Saki F et al (2012) Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants and its association with pneumothorax. Acta Med Iran 50:473–476

Khan IA, Wahab S, Khan RA et al (2010) Neonatal intracranial ischemia and hemorrhage: role of cranial sonography and CT scanning. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 47:89–94

Luu TM, Ment LR, Schneider KC et al (2009) Lasting effects of preterm birth and neonatal brain hemorrhage at 12 years of age. Pediatrics 123:1037–1044

Payne AH, Hintz SR, Hibbs AM et al (2013) Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low-gestational-age neonates with low-grade periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage. JAMA Pediatr 167:451–459

Kuban KC, Allred EN, O’Shea TM et al (2009) Cranial ultrasound lesions in the NICU predict cerebral palsy at age 2 years in children born at extremely low gestational age. J Child Neurol 24:63–72

O’Shea TM, Kuban KC, Allred EN et al (2008) Neonatal cranial ultrasound lesions and developmental delays at 2 years of age among extremely low gestational age children. Pediatrics 122:e662–669

Fowlie PW, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Gould CR et al (1998) Predicting outcome in very low birthweight infants using an objective measure of illness severity and cranial ultrasound scanning. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 78:F175–178

Perlman JM, Rollins N (2000) Surveillance protocol for the detection of intracranial abnormalities in premature neonates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154:822–826

Paul DA, Pearlman SA, Finkelstein MS et al (1999) Cranial sonography in very-low-birth-weight infants: do all infants need to be screened? Clin Pediatr 38:503–509

Hsu CL, Lee KL, Jeng MJ et al (2012) Cranial ultrasonographic findings in healthy full-term neonates: a retrospective review. J Chin Med Assoc 75:389–395

Brezan F, Ritivoiu M, Dragan A et al (2012) Preterm screening by transfontanelar ultrasound — results of a 5 years cohort study. Med Ultrason 14:204–210

Bhat V, Karam M, Saslow J et al (2012) Utility of performing routine head ultrasounds in preterm infants with gestational age 30–34 weeks. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25:116–119

Stenman C, Jamil S, Thorelius L et al (2013) Do radiologists agree on findings in radiographer-acquired sonographic examinations? J Ultrasound Med 32:513–518

Hintz SR, Slovis T, Bulas D et al (2007) Interobserver reliability and accuracy of cranial ultrasound scanning interpretation in premature infants. J Pediatr 150:592–596

El-Dib M, Massaro AN, Bulas D et al (2010) Neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental outcome of premature infants. Am J Perinatol 27:803–818

Ment LR, Bada HS, Barnes P et al (2002) Practice parameter. Neuroimaging of the neonate: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 58:1726–1738

Di Salvo DN (2001) A new view of the neonatal brain: clinical utility of supplemental neurologic US imaging windows. Radiographics 21:943–955

Barker LE, Luman ET, McCauley MM et al (2002) Assessing equivalence: an alternative to the use of difference tests for measuring disparities in vaccination coverage. Am J Epidemiol 156:1056–1061

De Vries LS, Volpe JJ (2013) Value of sequential MRI in preterm infants. Neurology 81:2062–2063

Kwon SH, Vasung L, Ment LR et al (2014) The role of neuroimaging in predicting neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm neonates. Clin Perinatol 41:257–283

Resch B, Jammernegg A, Perl E et al (2006) Correlation of grading and duration of periventricular echodensities with neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Pediatr Radiol 36:810–815

Van Wezel-Meijler G, van der Knaap MS, Oosting J et al (1999) Predictive value of neonatal MRI as compared to ultrasound in premature infants with mild periventricular white matter changes. Neuropediatrics 30:231–238

DiPietro MA, Brody BA, Teele RL (1986) Peritrigonal echogenic ‘blush’ on cranial sonography: pathologic correlates. AJR Am J Roentgenol 146:1067–1072

Enriquez G, Correa F, Lucaya J et al (2003) Potential pitfalls in cranial sonography. Pediatr Radiol 33:110–117

De Vries LS, Regev R, Pennock JM et al (1988) Ultrasound evolution and later outcome of infants with periventricular densities. Early Hum Dev 16:225–233

Jongmans M, Henderson S, de Vries L et al (1993) Duration of periventricular densities in preterm infants and neurological outcome at 6 years of age. Arch Dis Child 69:9–13

Trounce JQ, Rutter N, Levene MI (1986) Periventricular leucomalacia and intraventricular haemorrhage in the preterm neonate. Arch Dis Child 61:1196–1202

Veyrac C, Couture A, Saguintaah M et al (2006) Brain ultrasonography in the premature infant. Pediatr Radiol 36:626–635

Bethune M (2008) Time to reconsider our approach to echogenic intracardiac focus and choroid plexus cysts. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 48:137–141

Dormagen JB, Gaarder M, Drolsum A (2015) Standardized cine-loop documentation in abdominal ultrasound facilitates offline image interpretation. Acta Radiol 56:3–9

Jandzinski D, van Wijngaarden E, Dogra V et al (2007) Renal sonography with 2-dimensional versus cine organ imaging: preliminary results. J Ultrasound Med 26:635–644

Conflicts of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1

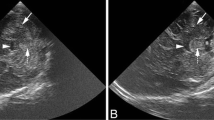

Sagittal static and coronal cinegraphic series demonstrate a left temporal lobe parenchymal hemorrhage in a premature boy (gestational age at birth 26 weeks, gestational age at imaging 26 weeks + 6 days). (GIF 30 kb)

ESM 1

(MP4 180 kb)

Online Resource 2

Coronal static and cinegraphic series demonstrate a left choroid plexus cyst (arrow) in a term girl (gestational age at birth 39 weeks + 2 days, gestational age at imaging 39 weeks + 5 days). (GIF 26 kb)

ESM 2

(MP4 123 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Dell, M.C., Cassady, C., Logsdon, G. et al. Cinegraphic versus Combined Static and Cinegraphic Imaging for Initial Cranial Ultrasound Screening in Premature Infants. Pediatr Radiol 45, 1706–1711 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-015-3382-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-015-3382-0