Abstract

Summary

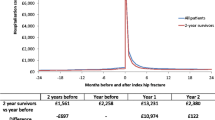

High direct incremental healthcare costs post-fracture are seen in the first year, but total costs from a third-party healthcare payer perspective eventually fall below pre-fracture levels. We attribute this to higher mortality among fracture cases who are already the heaviest users of healthcare (“healthy survivor bias”). Economic analyses that do not account for the possibility of a long-term reduction in direct healthcare costs in the post-fracture population may systematically overestimate the total economic burden of fracture.

Introduction

High healthcare costs in the first 1–2 years after an osteoporotic fracture are well recognized, but long-term costs are uncertain. We evaluated incremental costs of non-traumatic fractures up to 5 years from a third-party healthcare payer perspective.

Methods

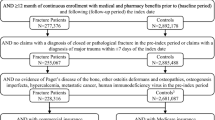

A total of 16,198 incident fracture cases and 48,594 matched non-fracture controls were identified in the province of Manitoba, Canada (1997–2002). We calculated the difference in median direct healthcare costs for the year pre-fracture and 5 years post-fracture expressed in 2009 Canadian dollars with adjustment for expected age-related healthcare cost increases.

Results

Incremental median costs for a hip fracture were highest in the first year ($25,306 in women, $21,396 in men), remaining above pre-fracture baseline to 5 years in women but falling below pre-fracture costs by 5 years in men. In those who survived 5 years following a hip fracture, incremental costs remained above pre-fracture costs at 5 years ($12,670 in women, $7,933 in men). Incremental costs were consistently increased for 5 years after spine fracture in women. Total incremental healthcare costs for all incident fractures combined showed a large increase over pre-fracture costs in the first year ($137 million in women, $57 million in men), but fell below pre-fracture costs within 3–4 years. Elevated total healthcare costs were seen at year 5 in women after wrist, humerus and spine fractures, but these were somewhat offset by decreases in total healthcare costs for other fractures.

Conclusions

High direct healthcare costs post-fracture are seen in the first year, but total costs eventually fall below pre-fracture levels. Among those who survive 5 years following a fracture, healthcare costs remain above pre-fracture levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos Int 11:669–674

Melton LJ III, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C et al (1992) Perspective. How many women have osteoporosis? J Bone Miner Res 7:1005–1010

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Berger C et al (2001) The influence of osteoporotic fractures on health-related quality of life in community-dwelling men and women across Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:903–908

Hallberg I, Rosenqvist AM, Kartous L et al (2004) Health-related quality of life after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:834–841

Abrahamsen B, van ST, Ariely R et al (2009) Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 20:1633–1650

Papaioannou A, Wiktorowicz ME, Adachi JD et al (2000) Mortality, independence in living and re-fracture, one year following hip fracture in Canadians. J Soc Obstet Gynaecol Can 22:591–597

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A et al (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:271–278

De Laet CE, van Hout BA, Burger H et al (1999) Incremental cost of medical care after hip fracture and first vertebral fracture: the Rotterdam study 1. Osteoporos Int 10:66–72

Pike C, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M et al (2010) Direct and indirect costs of non-vertebral fracture patients with osteoporosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 28:395–409

Shi N, Foley K, Lenhart G et al (2009) Direct healthcare costs of hip, vertebral, and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures. Bone 45:1084–1090

Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM et al (2007) High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA 298:2381–2388

Lindsay R, Burge RT, Strauss DM (2005) One year outcomes and costs following a vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 16:78–85

Ohsfeldt RL, Borisov NN, Sheer RL (2006) Fragility fracture-related direct medical costs in the first year following a nonvertebral fracture in a managed care setting. Osteoporos Int 17:252–258

Strom O, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N et al (2008) Long-term cost and effect on quality of life of osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Acta Orthop 79:269–280

Pike C, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M et al (2011) Economic burden of privately insured non-vertebral fracture patients with osteoporosis over a 2-year period in the US. Osteoporos Int 22:47–56

Nikitovic M, Wodchis WP, Krahn MD et al. (2012) Direct health-care costs attributed to hip fractures among seniors: a matched cohort study. Osteoporos Int

Leslie WD, Metge CJ, Azimaee M et al (2011) Direct costs of fractures in Canada and trends 1996-2006: a population-based cost-of-illness analysis. J Bone Miner Res 26:2419–2429

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (2011) Population Health Research Data Repository. University of Manitoba: U of M — Medicine Last accessed: Nov. 11, 2012. URL: http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/medicine/units/mchp/resources/repository/health_admin.html

Kozyrskyj AL, Mustard CA (1998) Validation of an electronic, population-based prescription database. Ann Pharmacother 32:1152–1157

Morin S, Lix LM, Azimaee M et al (2012) Institutionalization following incident non-traumatic fractures in community-dwelling men and women. Osteoporos Int 23:2381–2386

Curtis JR, Taylor AJ, Matthews RS et al (2009) "Pathologic" fractures: should these be included in epidemiologic studies of osteoporotic fractures? Osteoporos Int 20:1969–1972

Shanahan M, Steinbach C, Burchill C et al (1999) Adding up provincial expenditures on health care for Manitobans: a POPULIS project. Population Health Information System. Med Care 37:JS60–JS82

Baladi JF, Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (1996) A Guidance Document for the Costing Process. Health Technology Assessment, Ottawa, Canada Accessed: Nov. 11, 2012. URL: http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/costing_e.pdf.

Finlayson G, Reimer J, Dahl J et al. (2010) The direct cost of hospitalizations in Manitoba 2005/06. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Accessed: Nov. 11, 2012. URL: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/HospCost_fullreport.pdf#page=27&view=Fit.

Finlayson G, Ekuma O, Yogendran MS et al. (2010) The additional cost of chronic disease in Manitoba. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Accessed: Nov. 11, 2012. URL: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/Chronic_Cost.pdf.

Adam T, Koopmanschap MA, Evans DB (2003) Cost-effectiveness analysis: can we reduce variability in costing methods? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 19:407–420

Pink GH, Bolley HB (1994) Physicians in health care management: 4. Case Mix Groups and Resource Intensity Weights: physicians and hospital funding. CMAJ 150:1255–1261

Pink GH, Bolley HB (1994) Physicians in health care management: 3. Case Mix Groups and Resource Intensity Weights: an overview for physicians. CMAJ 150:889–894

Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Becker DJ et al (2009) Health care expenditures associated with skeletal fractures among Medicare beneficiaries, 1999–2005. J Bone Miner Res 24:2050–2055

Morin S, Lix LM, Azimaee M, Metge C, Caetano P, Leslie WD (2011) Mortality rates after incident non-traumatic fractures in older men and women. Osteoporos Int 22(9):2439–48

Rosansky SJ, Eggers P, Jackson K et al (2011) Early start of hemodialysis may be harmful. Arch Intern Med 171:396–403

Zethraeus N, Strom O, Borgstrom F et al (2008) The cost-effectiveness of the treatment of high risk women with osteoporosis, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 19:81–827

Strom O, Borgstrom F, Kleman M et al (2010) FRAX and its applications in health economics—cost-effectiveness and intervention thresholds using bazedoxifene in a Swedish setting as an example. Bone 47:430–437

Strom O, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA et al (2009) Incorporating adherence into health economic modelling of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 20:23–34

Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O et al (2006) Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 17:637–650

Cooper C, Mitchell P, Kanis JA (2011) Breaking the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 22:2049–2050

Leslie WD, LaBine L, Klassen P et al (2012) Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 184:290–296

Nevitt MC, Ettinger B, Black DM et al (1998) The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 128:793–800

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy for use of data contained in the Population Health Research Data Repository (HIPC project # 2008/2009-16). The authors also thank Mr. Mahmoud Azimaee for SAS programming support. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Manitoba Health, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. This work was funded through a research grant from Amgen Canada Ltd. The funding source had no access to the data prior to publication, no input into the writing of the manuscript, and no input in the decision to publish the results. S.R.M. holds the Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management from the Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (University of Alberta) and receives salary support from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research–AIHS (Health Scholar). L.M.L. receives salary support from the University of Saskatchewan Centennial Chair Program. S.N.M. is chercheur-clinicien boursier des Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

Conflicts of interest

William Leslie — speaker bureau: Amgen; research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Genzyme; advisory boards: Novartis, Amgen. Colleen Metge — research grant: Amgen. Lisa Lix — research grant: Amgen. Suzanne Morin — consultant to: Amgen, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Merck; speaker bureau: Amgen, Novartis; research grant: Amgen. Sumit Majumdar — none. Gregory Finlayson — none.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leslie, W.D., Lix, L.M., Finlayson, G.S. et al. Direct healthcare costs for 5 years post-fracture in Canada. Osteoporos Int 24, 1697–1705 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2232-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2232-2