Abstract

This paper estimates a high-frequency New-Keynesian Phillips curve via the generalized method of moments. Allowing for higher-than-usual frequencies strongly mitigates the problems of small-sample bias and structural breaks. Applying a daily frequency allows us to obtain estimates for the Calvo parameter of nominal rigidity over a very short period—for instance for the recent financial and economic crisis—which can then be easily transformed into their low-frequency equivalences. With Argentine data from the end of 2007 to the beginning of 2011 we estimate the daily Calvo parameter and find that on average prices remain fixed for approximately two to three months which is in line with recent microeconomic evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an empirical investigation see Fernández-Villaverde and Rubio-Ramírez (2007).

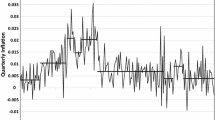

See the corresponding Figure in the Appendix B and D’Amato et al. (2007).

Alternatively to the purely forward-looking NKPC, we could also apply a hybrid version of the NKPC. This can be brought about either by assuming rule-of-thumb price setters à la Galí and Gertler (1999) or by assuming that non-reset prices are indexed to inflation as in Christinao et al. (2005). However, given that price changes are—in general—costly, the assumption of indexation to daily inflation rates is simply implausible. Furthermore, the estimation of a rule-of-thumb based hybrid NKPC yields the result that the share of backward-looking agents is not statistically different from zero for each estimation considered in this paper. Thus, the hypothesis of a hybrid NKPC on a daily basis—in our setting—has to be rejected. The insignificance of lagged inflation might be the result of the low autocorrelation of daily inflation, as can be seen from the Fig. 1 (lower panel) in the Appendix B. To support this presumption we perform a serial correlation Lagrange multiplier test on inflation (Godfrey 1978 and Breusch 1979) for lag lengths between 2 days and up to 1 week. In neither case we find any statistical significant lags at the 5 % confidence level. This result implies that daily inflation is not (or only very marginally) autocorrelated. Consequently, we restrict ourselves to the purely forward-looking NKPC.

Note that there is no change in the price-setting behavior of the representative firm on a higher frequency, i.e., it is still the aim of the firm to minimize the (discounted) expected deviations of all its future optimal prices (defined as the real marginal costs times a mark-up) from the future market prices. Here the future is not denoted as the next quarter, but as the next day instead. In other words, due to the underlying rational expectation hypothesis firms use all information available when applying their optimization which leads to a quick adaptation to new information, i.e., changes in the economic environment. Obviously, this is in favor of the underlying Calvo (1983) price-setting scheme, which is specified in continuous time rather than discrete time.

The following procedure can also be found in the modeling of search and matching processes; see, e.g., Mortensen (1986) and Rogerson et al. (2005). Anagnostopoulos and Giannitsarou (2010) analyze local stability under consideration of changes in the period length quite similar to Flaschel et al. (2008).

Note that obviously the probability for not changing the price is higher at a higher frequency, i.e., at a period length of a day relative to a quarter. Furthermore, the stickiness remains the same in the sense that on average a firm is allowed to reset the price every \(1/[1-\theta (h_i)]\) periods of length \(h_i\) (say a day) which—independently of \(h_i\)—means every \(h_i/[1-\theta (h_i)]=h_i/[1-1+h_i(1-\theta (h_q))]=1/(1-\theta (h_q))\) quarters, respectively.

Note that in addition neither the domestic and the foreign output gaps (as we will discuss below) nor the labor share of income stand for appropriate proxies, since both are also not available in daily magnitudes.

Under the assumption of complete securities markets, Eq. (6) implies that relative consumption and hence (in a general equilibrium framework) the output gap relation across countries is proportional to the terms of trade. For a formal proof refer to Lubik and Schorfheide (2007) and Appendix A of Galí and Monacelli (2005). For an empirical discussion see Chari et al. (2002) among others.

A related approach to estimate an open economy NKPC for a quarterly frequency has been applied by Mihailov et al. (2011a).

Holmberg (2006) even shows that CPI data results in more realistic estimates for an open economy NKPC in Sweden compared to the use of the GDP-deflator. In empirical applications of the closed economy version of the NKPC this approach is common too due to reasons of data availability. Recent examples are, among others, Ramos-Francia and Torres (2008) and Yazgan and Yilmazkuday (2005). Moreover, Nason and Smith (2008) apply both measures to test for robustness and find the differences in performance to be negligible for the United States.

In particular, the prices of 150 products are checked online every day. This methodology is sufficient since 100 % of all products in Argentine supermarkets can also be found online (Cavallo 2012a). For a thorough discussion of the methodology of the billion prices project at MIT Sloan, we refer to Cavallo (2012a, b), Cavallo and Rigobon (2011), www.inflacionverdadera.com and www.billionpricesproject.com.

According to Eq. (4) the discount rate in daily magnitudes is than equal to \(\beta (h_d)=1/(1+\frac{h_d}{h_q} \rho (h_q))=0.999\) where \(h_d=1/75\) and \(h_q=1\).

Following Galí and Gertler (1999), we define deviations from steady state in terms of demeaned time series. The results are robust, however, also to the use of the Hodrick-Prescott filter with \(\lambda =6{,}812{,}100\) for daily observations.

This result only holds for the standard flex-price model. Once we take into account for instance non-separable utility between consumption and money-in-the-utility function, shopping time models or cash-in-advance constraints, monetary policy is—although in quantitative terms very little—effective (Walsh 2010).

References

Aadland D (2001) High frequency real business cycles. J Monetary Econ 48:271–292

Abe N, Tonogi A (2010) Micro and macro price dynamics in daily data. J Monetary Econ 57:716–728

Alvarez LJ (2008) What do micro price data tell us on the validity of the New Keynesian Phillips curve? Econ: The Open-Access, Open-Assess E-J 2:1–38

Anagnostopoulos A, Giannitsarou C (2010) Modeling time and macroeconomic dynamics. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 8050

Bils M, Klenow PJ (2004) Some evidence on the importance of sticky prices. J Polit Econ 112:947–985

Breusch TS (1979) Testing for autocorrelation in dynamic linear models. Aust Econ Pap 17:334–355

Calvo GA (1983) Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. J Monetary Econ 12:383–398

Cavallo A (2010) Scraped data and sticky prices: frequency, hazards, and synchronization. MIT Sloan Working Paper

Cavallo A (2012a) Scraped data and sticky prices. MIT Sloan Working Paper

Cavallo A (2012b) Online and official price indexes: measuring Argentina’s inflation. MIT Sloan Working Paper

Cavallo A, Rigobon R (2011) The distribution of the size of price changes. NBER Working Paper No. 16760

Chari VV, Kehoe PJ, McGrattan ER (2002) Can sticky price models generate volatile and persistent real exchange rates? Rev Econ Stud 69:533–563

Christiano LJ (1985) A method for estimating the timing interval in a linear econometric model, with an application to Taylor’s model of staggered contracts. J Econ Dyn Control 9:363–404

Christinao LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (2005) Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. J Polit Econ 113:1–45

Clarida R, Galí J, Gertler M (2001) Optimal monetary policy in open versus closed economies: an integrated approach. AM Econ Rev 91:248–252

Clarida R, Galí J, Gertler M (2002) A simple framework for international monetary policy analysis. J Monetary Econ 49:879–904

D’Amato L, Garegnani ML, Sotes Paladino JM (2007) Inflation persistence and changes in the monetary regime: the Argentine case. Working Paper 2007|23, Banco Central de la República Argentina

D’Amato L, Garegnani ML (2009) Studying the short-run dynamics of inflation: estimating a hybrid New-Keynesian Phillips curve for Argentina (1993–2007). Working Paper 2009|40, Banco Central de la República Argentina

Dhyne E, Alvarez LJ, Bihan HL, Veronese G, Dias D, Hoffmann J, Jonker N, Lunnemann P, Rumler F, Vilmunen J (2006) Price changes in the Euro Area and the United States: some facts from individual consumer price data. J Econ Perspect 20:171–192

Ellis C (2009) Do supermarket prices change from week to week? Bank of England Working Paper No. 378

Escudé GJ (2007) ARGEM: a DSGE model with banks and monetary policy regimes with two feedback rules, calibrated for Argentina. Working Paper 2007|21, Banco Central de la República Argentina

Escudé GJ (2009) ARGEMmy: an intermediate DSGE calibrated/estimated for Argentina: two policy rules are often better than one. Working Paper 2009|42, Banco Central de la República Argentina

Fernández-Villaverde J, Rubio-Ramírez JF (2007) How structural are structural parameters? NBER Working Paper No. 13166

Flaschel P, Franke R, Proaño CR (2008) On equilibrium determinacy in New Keynesian models with staggered wage and price setting. BE J Macroecon, Article 31

Franke R, Sacht S (forthcoming) Some observations in the high-frequency versions of a standard New-Keynesian model. B Econ Res

Fuhrer JC, Moore GR, Schuh SD (1995) Estimating the linear-quadratic inventory model: maximum likelihood versus generalized method of moments. J Monetary Econ 35:115–157

Galí J (2008) Monetary policy, inflation and the business cycle: an introduction to the New Keynesian framework. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Galí J, Gertler M (1999) Inflation dynamics: a structural econometric analysis. J Monetary Econ 44:195–222

Galí J, Gertler M, Lopez-Salido JD (2001) European inflation dynamics. Eur Econ Rev 45:1237–1270

Galí J, Monacelli T (2005) Monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. Rev Econ Stud 72:707–734

Godfrey LG (1978) Testing against general autoregressive and moving average error models when the regressors include lagged dependent variables. Econometrica 46:1293–1301

Gouvea S (2007) Price rigidity in Brazil: evidence from CPI micro data. Working Papers Series No. 143, Central Bank of Brazil

Hansen LP (1982) Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica 50:1029–54

Holmberg K (2006) Derivation and estimation of a New Keynesian Phillips curve in a small open economy. Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series No. 197

Ireland PN (2005) The monetary transmission mechanism. Working Papers No. 06–1, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

Khalaf L, Kichian M (2004) Estimating New Keynesian Phillips curves using exact methods. Bank of Canada Working Papers No. 04–11

Kehoe PJ, Midrigan V (2007) Sales and the real effects of monetary policy. Working Papers No. 652, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Klenow PJ, Malin BA (2010) Microeconomic evidence on price-setting. NBER Working Paper No. 15826

Leitemo K, Söderström U (2005) Simple monetary policy rules and exchange rate uncertainty. J Int Money Financ 24:481–507

Lindé J (2005) Estimating New-Keynesian Phillips curves: a full information maximum likelihood approach. J Monetary Econ 52:1135–1149

Lubik T, Schorfheide F (2007) Do central banks respond to exchange rate movements? A structural investigation. J Monetary Econ 54:1069–1087

Ma A (2002) GMM estimation of the New Phillips curve. Econ Lett 76:411–417

Mavroides S (2007) Testing the New Keynesian Phillips curve without assuming identification. Brown University Working Papers

McCallum BT (1976) Rational expectations and the natural rate hypothesis: some consistent estimates. Econometrica 44:43–52

Medina JP, Rappoport D, Soto C (2007) Dinámica de ajuste de precios: evidencia de datos microeconómicos para Chile. J Econ Chilena 10:5–26

Mihailov A, Rumler F, Scharler J (2011a) The small open-economy New Keynesian Phillips curve: empirical evidence and implied inflation dynamics. Open Econ Rev 22:317–337

Mihailov A, Rumler F, Scharler J (2011b) Inflation dynamics in the new EU member states: how relevant are external factors? Rev Int Econ 19:65–76

Monacelli T (2004) Into the Mussa puzzle: monetary policy regimes and the real exchange rate in a small open economy. J Int Econ 62:191–217

Morandé F, Tejada M (2008) Price stickiness in emerging economies: empirical evidence for four Latin-American countries. Working Papers wp286, University of Chile, Department of Economics, Chile

Mortensen DT (1986) Job search and labor market analysis. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (ed.) Handb Labor Econ, 1st edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 849–919

Nason MN, Smith GW (2008) The New Keynesian Phillips curve: lessons from single-equation econometric estimation. Econ Q 94:361–395

Ramos-Francia M, Torres A (2008) Inflation dynamics in Mexico: a characterization using the New Phillips curve. N Am J Econ Financ 19:274–289

Rogerson R, Shimer R, Wright R (2005) Search-theoretic models of the labor market: a survey. J Econ Lit 43:959–988

Stock JH, Wright JH, Yogo M (2002) A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat 20:518–529

Svensson LEO, Woodford M (2003) Indicator variables for optimal policy. J Monetary Econ 50:691–720

Taylor JB (1999) Staggered price and wage setting in macroeconomics. In: Taylor JB, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of macroeconomics, 1st edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1009–1050

Walsh C (2010) Monetary theory and policy. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Woodford M (2003) Interest and prices: foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

World Bank (2009) World development indicators.

World Bank (2010) Argentina trade brief. World trade indicators 2009/10: Country Trade Briefs. World Bank, Washington, DC

Yazgan ME, Yilmazkuday H (2005) Inflation dynamics of Turkey: a structural estimation. Stud Nonlinear Dyn E 9:1–15

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Reiner Franke, Matthias Hartmann, Henning Weber and Hans-Werner Wohltmann as well as two anonymous referees for helpful comments. Furthermore we would like to thank the participants of the 2011 Conference on Modeling High Frequency Data in Finance III at the Stevens Institute of Technology (New Jersey, USA) and the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics at the University of Lucerne (Switzerland) for the discussion of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A: Household’s optimization problem

Following Woodford (2003) and Galí (2008) we consider a standard intertemporal utility function of a representative household, which is additive separable in consumption \(C_t\), in real money holding \(M_t/P_t\) (where \(P_t\) is the price level) and in leisure (labor supply \(N_t\), respectively), subject to the underlying frequency in daily magnitudes:

where \(\sigma > 0\) represents the inverse intertemporal elasticity of substitution between present and future consumption of domestic goods, \(\eta > 0\) is the inverse of the substitution elasticity of labor, \(\psi >0\) stands for the inverse of the elasticity of money demand, \(\beta (h_d) >0\) is the (frequency-dependent) discount factor and \(E_t\) stands for the expectations operator.

The period-by-period budget constraint is characterized by money and bond holdings of the representative household and is given in real terms by

where \(M_t (B_t)\) is the household’s nominal holding of money (one-period bonds). Bonds pay a nominal interest rate \(i_t\) and \(1+i_t\) represents the gross nominal interest rate. \(W_t\) denotes the nominal wage. Real profits received from firms are equal to \(\Pi _t^r\) and \(T_t^n\) are nominal lump-sum taxes or transfers. Note that \(\Delta M_{t+k}=M_{t+k}-M_{t+k-1}\) holds.

The household seeks to maximize (17) subject to (18) and the following cash-in-advance constraint:

i.e., nominal consumption expenditures are not allowed to exceed the nominal money holdings of the household. This expression is given in real terms and under consideration of \(y_t=c_t\) in Sect. 2. In can be easily shown that the optimality condition for the demand of real money holdings (in daily magnitudes) is given by:

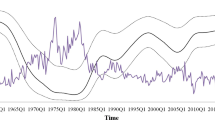

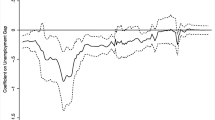

1.2 Appendix B: Time series for the Argentine consumer price index (CPI)

See Fig. 1.

The upper panel depicts the development in the Argentine CPI in quarterly magnitudes from 1995Q1 until 2010Q4. The lower panel depicts the corresponding Argentine CPI in daily magnitudes (scraped data index) from 2007Q4 until 2010Q4. Quarterly data is taken from Datastream\(^\mathrm{\textregistered }\). Daily data is provided by www.inflacionverdadera.com

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahrens, S., Sacht, S. Estimating a high-frequency New-Keynesian Phillips curve. Empir Econ 46, 607–628 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0684-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0684-7