Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We aimed to identify circulating microRNA (miRNA) that predicts clinical progression in a cohort of 123 children with new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Plasma samples were prospectively obtained at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 60 months after diagnosis from a subset of 40 children from the Danish Remission Phase Cohort, and profiled for miRNAs. At the same time points, meal-stimulated C-peptide and HbA1c levels were measured and insulin-dose adjusted HbA1c (IDAA1c) calculated. miRNAs that at 3 months after diagnosis predicted residual beta cell function and glycaemic control in this subgroup were further validated in the remaining cohort (n = 83). Statistical analysis of miRNA prediction for disease progression was performed by multiple linear regression analysis adjusted for age and sex.

Results

In the discovery analysis, six miRNAs (hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-194-5p, hsa-miR-197-3p, hsa-miR-301a-3p and hsa-miR-375) at 3 months correlated with residual beta cell function 6–12 months after diagnosis. Stimulated C-peptide at 12 months was predicted by hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months (p = 0.034). A doubling of this miRNA level corresponded to a sixfold higher stimulated C-peptide level. In addition, a doubling of hsa-miR-24-3p and hsa-miR-146a-5p levels at 3 months corresponded to a 4.2% (p < 0.014) and 3.5% (p < 0.022) lower IDAA1c value at 12 months. Analysis of the remaining cohort confirmed the initial finding for hsa-miR-197-3p (p = 0.018). The target genes for the six miRNAs revealed significant enrichment for pathways related to gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor and angiogenesis pathways.

Conclusions/interpretation

The miRNA hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months was the strongest predictor of residual beta cell function 1 year after diagnosis in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past twenty years, the interest in the expression of circulating variations of microRNA (miRNA) has increased, specifically in regard to their potential role as biomarkers for several diseases. The leading hypothesis is that differential miRNA expression profiles may provide insight into pathological processes related to disease origin and thereby potentially serve as non-invasive predictive biomarkers for diagnosis and disease progression [1].

miRNAs belong to the class of evolutionarily conserved non coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and are small, single-stranded molecules (18–25 nucleotides). They predominantly regulate gene expression at a post-transcriptional level through partial base-pairing with their target mRNAs to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) [2, 3]. The binding of miRNA to target mRNA leads to either decreased translational efficiency or repression of mRNA levels, thus indicating that destabilisation of target mRNAs is the main reason for reduced protein output [4]. A fast-growing wealth of evidence shows the importance of miRNAs as fundamental master regulators in cell cycle processes, and their dysregulation is indicated to be involved in various pathophysiologies, including autoimmune and metabolic disorders [5, 6]. Circulating, cell-free miRNAs are stabilised and protected from RNase degradation mainly by inclusion in microvesicles or exosomes [7]. Studies have also demonstrated that endogenous plasma miRNAs are protected from degradation in the RNase-rich environment of the blood by the argonaute 2 complex [8].

The pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus still remains unclear but it is well established that the immune system initiates a cascade of events that lead to the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells [9, 10]. The end-stage condition is a lack of endogenous insulin production, resulting in elevated blood glucose levels and lifelong insulin treatment. Clinical challenges in the early and precise diagnosis of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes are obvious, and optimal treatment is crucial to obtain the best prognosis and avoid severe late complications such as microvascular and macrovascular injuries, often associated with the disease [11].

Over the past few years, evidence has accumulated for the role of specific miRNAs in type 1 diabetes mellitus [12–19]. However, the prognostic potential of miRNAs in type 1 diabetes has been largely unexplored. We hypothesised that biomarkers, in the form of miRNAs in plasma from children with recent-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus would be able to predict the decline or regeneration of endogenous residual beta cell function. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify circulating miRNA that predicts clinical progression as assessed by stimulated C-peptide, HbA1c and insulin-dose-adjusted HbA1c (IDAA1c) in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Study cohort

The Danish Remission Phase Cohort is a longitudinal multicentre study that was conducted prospectively in four paediatric outpatient clinics over 2004–2005. A total of 126 children (61 girls) younger than 17 years old and with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus were included in the study. Demographic and anthropometric data, as well as blood samples for centralised measurement of HbA1c and meal-stimulated C-peptide, were collected prospectively 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after diagnosis (±1 week) for all individuals, and also after 60 months in a subset of 40 patients. For three individuals, there was insufficient material for miRNA analysis. Compared with the entire cohort (n = 123), the 40 patients in the subgroup who completed follow-up at a diabetes duration of 5 years were slightly younger, with a lower BMI, and a lower postprandial C-peptide levels 12 months after diagnosis. However, the subgroup was similar to the entire cohort in terms of sex distribution and HbA1c levels. Causes for dropout or loss at the 5 year follow-up were transferral of adolescents to adult clinics, changes of residence and unwillingness to participate. A complete overview of the characteristics of the original study cohort can be found in Table 1 and earlier publications [20, 21]. Insulin dose (U kg–1 24 h–1) and IDAA1c were recorded. IDAA1c is an indirect HbA1c- and insulin-weighted measure of residual beta cell function and was calculated on basis of the actual insulin dose and HbA1c as follows: IDAA1c = HbA1c (%) + (4 × insulin dose [U kg–1 24 h–1]) [22]. Plasma samples were collected using a highly standardised protocol in order to avoid preanalytical variations, and were stored at –80°C until further use [23]. The diagnosis of diabetes was classified according to World Health Organization criteria [24]. Ninety-six per cent of samples were positive for at least one autoantibody 1 month after diagnosis (GAD65A 60.3%, insulin autoantibody 82.5%, insulinoma-associated antigen 2 antibody 69.0% and zinc transporter 8 autoantibody 62%) [20].

Exclusion criteria included suspected non-type 1 diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes, MODY or secondary diabetes), decline of enrolment by patients or parents, and initial treatment outside of the study centre for more than 5 days (if patients were initially treated outside of the study centre for ≤5 days, the patient was included and the data necessary for the study was requested from the referring hospital). The study was performed according to the criteria of the Helsinki II Declaration and was approved by the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (journal number H-KA-04010-m). Older children gave their assent and all parents or guardians gave written informed consent.

miRNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

miRNA isolation was performed on a total of 182 samples from the 40 children who participated in the 60 month visit. Total RNA was extracted from 200 μl EDTA-plasma using the miRCURY RNA isolation kit biofluids (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Carrier RNA 1 μg per 60 μl Lysis Solution and RNA spike-in mixture were added to each sample (Exiqon). RNA (7 μl) was reverse-transcribed in 35 μl reactions using the miRCURY LNA Universal RT miRNA PCR, Polyadenylation and cDNA synthesis kit (Exiqon). cDNA was diluted 50× and assayed in 10 μl reaction volumes using the miRCURY LNA Universal RT miRNA PCR human serum/plasma panel (v3; Exiqon), which included 179 specific human miRNAs (several of which targeted immunological pathways), with ExiLENT SYBR Green master mix (Exiqon). For the subsequent validation study, RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed as described above. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using a Custom Pick-&-Mix panel and ExiLENT SYBR Master Mix (Exiqon). All RT-qPCR assays were performed using a LightCycler480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Hvidovre, Denmark) in 384-well plates.

Quality control

Quality control was carried out on a subset of samples using synthetic spike-in RNAs to analyse the robustness of the RNA isolation process and quality of isolated miRNA. The RNA isolation controls (UniSp2, UniSp4 and UniSp5; Exiqon) were added to the purified RNA and were used to detect differences in extraction efficiency. The cDNA synthesis control (UniSp6; Exiqon) was added in the reverse transcription reaction, to evaluate the efficacy of the reverse transcription process. In addition, a DNA spike-in (Sp3; Exiqon) was present on all panels. Haemolysis was assessed by the ratio between hsa-miR-451a (which is expressed in erythrocytes) and hsa-miR-23a-3p (which is relatively stable in plasma and serum and not affected by haemolysis) [25]. The difference in crossing point (ΔCp) between miR-23a-3p and miR-451a provides a good measure of the degree of haemolysis, with values >5 indicating possible erythrocyte miRNA contamination [25].

Normalisation

All individual samples (n = 182) were run on a predefined assay panel of 179 specific human miRNAs. From the initial profiling, the 100 miRNAs with complete data were employed for the global mean method for normalisation of the data as this was found to be the most stable normaliser [26].

Statistical analysis and identification of candidate miRNAs

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Stimulated C-peptide and miRNA levels were studied on a logarithmic scale (loge).

Prediction of stimulated C-peptide, IDAA1c and HbA1c at 6 and 12 months was done by multiple linear regression analysis for each miRNA separately, including the covariates for sex and age. For each outcome (stimulated C-peptide, IDAA1c and HbA1c) at each time point (6 and 12 months) separately, multiple testing correction was applied across 688 analyses (172 miRNAs at time points 1, 3, 6 and 12 months) using the Hochberg method [27]. Values of p <0.05 were considered significant. Samples below the detection limit (the number of Cp cycles reaching 37) were included by imputing the covariate value as the detection limit.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Pearson’s test p values were used for scatter plots and regression lines for the correlation between age and hsa-miR-197-3p. Partial correlation coefficients between loge C-peptide and hsa-miR-197-3p accounting for sex and age were calculated.

Validation of candidate miRNAs

Six candidate miRNAs with significantly predictive value for stimulated C-peptide, HbA1c and IDAA1c in the subgroup of 40 children were analysed in the remaining cohort of 83 children in samples taken 3 months after diagnosis. As only six miRNAs were analysed, two additional miRNAs (hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-425-5p) were selected as endogenous controls for normalisation based on results from the initial profiling analysis. These two miRNAs showed high stability (NormFinder, http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/64/15/5245.long, accessed December 2013) and strong correlation with the global mean (r 2 = 0.99). p values in the validation study were not corrected for multiple testing, although adjustments were made for sex and age.

miRNA target prediction and pathway analysis

The miRNA targets were retrieved from MiRWALK (http://zmf.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/apps/zmf/mirwalk2/, accessed 15 April 2016) [28] and miRTarBase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/, accessed 06 June 2016) [29]. miRNA target interaction maps were retrieved based on cross-linking, immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (CLIP-Seq) from starBase database v2.0 (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/, accessed 27 October 2016) [30]. Target genes were selected based on a minimum of three prediction tools and CLIP-Seq overlap with biological complexity ≥1 (a measure of reproducibility between biological replicates or experiments in order to further reduce the number of false-positive results). The target genes were further filtered based on a CLIP-Seq read number ≥1. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway-based over-enrichment tests for miRNA target genes were performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/, accessed 18 August 2016) [31] and the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationship (PANTHER; http://pantherdb.org/, 18 August 2016) [32]. The enrichment for GO terms in the biological process, molecular function and cellular component category was identified based on the binomial test in PANTHER. The KEGG and PANTHER pathways were used for pathway-based enrichment of the target genes. The total protein coding genes in the human genome were used as the reference list.

A complete overview outlining the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Results

Quality control of samples using ‘spike-ins’ (technical controls)

The RNA spike-ins showed low variation in Cp between samples in RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, indicating that extraction, reverse transcription and qPCR were successful and none of the samples contained inhibitors. The ratio between the miRNAs hsa-miR-451a and hsa-miR-23a-3p varied between 5 and −2, indicating that the samples were not affected by haemolysis. Thus, overall, these findings show a good and similar level of sample quality and reproducibility of processes for miRNA profiling.

Candidate miRNAs associated with residual beta cell function and glycaemic control

Out of the 179 miRNAs tested, 100 were detectable across all samples (1, 3, 6, 12 and 60 months), with an average of 163 miRNAs detectable per sample (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Multiple linear regression analysis showed that six miRNAs (hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-194-5p, hsa-miR-197-3p, hsa-miR-301a-3p and hsa-miR-375) 3 months after diagnosis predicted the levels of stimulated C-peptide, HbA1c or IDAA1c 6 or 12 months after diagnosis (Table 2). Only significant observations are shown in Table 2. At 1 month after diagnosis, no miRNAs had any predictive value.

Stimulated C-peptide at 12 months was predicted by hsa-miR-197-3p measured 3 months after diagnosis (p = 0.034) (Table 2). C-peptide is considered on a natural log scale, and therefore the value of 1.80 for C-peptide (12 months) corresponds to a factor of C-peptide of e 1.80 = 6.05. However, when the baseline C-peptide value (1 month after diagnosis) was included in the statistical model as a response, the significance did not remain after correction for multiple testing (unadjusted p value 0.00019, adjusted p value 0.13; data not shown). Additionally, a doubling of the miRNAs hsa-miR-24-3p and hsa-miR-146a-5p measured at 3 months corresponded to a 4.23% and 3.49% decrease in IDAA1c 12 months after diagnosis (p < 0.014 and p < 0.022, respectively). None of the measured miRNAs could predict residual beta cell function or glycaemic control 60 months after diagnosis. Only a limited number of miRNAs (n = 8) showed a differential expression over time (p < 0.05; ESM Table 1, marked with an asterisk). Whether this is an effect related to age or duration of disease has not yet been investigated. However, there was no overlap between these eight differentially expressed miRNAs and the six candidate miRNAs identified with predictive value.

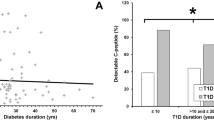

Age had no significant effect on the level of hsa-miR-197-3p, both variables being measured 3 months after diagnosis (r = 0.22, p = 0.22) (Fig. 2).

The effect of age on hsa-miR-197-3p 3 months after diagnosis. The graph shows the relationship between age at disease onset of the study participants and the normalised expression levels of hsa-miR-197-3p, both measured 3 months after diagnosis. No significant effect of age on hsa-miR-197-3p level (r = 0.22, p = 0.22) was seen at this time point. ΔCp, miRNA expression level normalised to the global mean

Validation of the candidate miRNAs

The six miRNAs (hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-194-5p, hsa-miR-197-3p, hsa-miR-301a-3p and hsa-miR-375) were further validated in the remaining cohort (n = 83). This analysis confirmed the initial finding that the level of hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months predicted stimulated C-peptide concentrations 6 and 12 months after diagnosis (p < 0.02; (Table 2)), with an estimated loge C-peptide of 0.65 at 6 months, and 0.75 at 12 months, suggesting a 1.9-fold and 2.1-fold higher stimulated C-peptide level at 6 months and 12 months, respectively.

Scatter plots comparing the levels of hsa-miR-197-3p and stimulated C-peptide in both the discovery and validation cohorts at 6 and 12 months are shown in Fig. 3. These indicate a significant association between the two variables in both cohorts, with partial correlation coefficients accounting for sex and age (r values between 0.27 and 0.66).

Correlation between hsa-miR-197-3p expression and loge C-peptide levels at 6 and 12 months. Scatter plots comparing expression levels (normalised to the global mean [ΔCp]) of hsa-miR-197-3p and loge C-peptide (pmol/l) in (a) the Discovery cohort (6 months), r = 0.36, p = 0.048, (b) the Validation cohort (6 months), r = 0.28, p = 0.013, (c) the Discovery cohort (12 months), r = 0.66, p < 0.0001, and (d) Validation cohort (12 months), r = 0.27, p = 0.018. r values represent partial correlations accounting for sex and age

Identification of miRNA target genes

In total, 825 unique target genes were identified, with CLIP-Seq overlap for the six candidate miRNAs predicting residual beta cell function and IDAA1c. The functional annotation of the target genes based on GO analyses revealed significantly enriched GO terms in biological processes, molecular function and the cellular component category (Table 3). The pathway-based annotation revealed enrichment for the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway (p = 3.91 × 10−3) and angiogenesis (p = 2.37 × 10−2) (Table 3). We also observed significant enrichment for various transcriptional, signalling and metabolic processes in the biological process category (Table 3).

Out of ∼400 predicted target genes for hsa-miR-197-3p, only six genes are supported by strong experimental evidence, such as Reporter Gene Assay data [28, 29]; TUSC2, NSUN5, CD82, BMF, PMAIP1, and MTHFD1. TUSC2 and CD82 are cancer-related genes, NSUN5 functions as a methyltransferase, and BMF and PMAIP1 are involved in various apoptosis pathways. MTHFD1 is involved in the metabolism of vitamins and cofactors and histidine degradation.

Discussion

The rate of decline of endogenous insulin production in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus varies considerably between individuals. Biomarkers that can predict the rate of loss of residual beta cell function will be of immense clinical value for the optimisation of current therapies and design of new treatment modalities to prolong endogenous insulin production. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to comprehensively investigate which miRNAs may influence beta cell function in terms of stimulated C-peptide production and glycaemic control after diagnosis.

Six miRNAs were associated with residual beta cell function and glycaemic control during the first year after disease onset in the 40 patients who completed follow-up at disease duration of 5 years. In the entire cohort, only hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months was able to predict stimulated C-peptide levels at 6 and 12 months after diagnosis. This was also illustrated by the significant partial correlation between hsa-miR-197-3p and stimulated C-peptide levels in the discovery and validation cohorts. However, when baseline C-peptide at 1 month was included in the statistical model, it weakened the impact of miR-197-3p for predicting stimulated C-peptide levels. At 1 month after diagnosis none of the miRNAs had any predictive value for residual beta cell function. This finding may suggest that the metabolic dysregulation was not completely recovered at this time point. At 3 months, most of the patients were in partial remission with improved residual beta cell function, as assessed by increased levels of stimulated C-peptide. Age of onset had no impact on the hsa-miR-197-3p level 3 months after diagnosis, which indicates that hsa-miR-197-3p level is independent of age at this time point. This implies that the hsa-miR-197-3p level can be referenced to other children without age adjustment. By contrast, age has a strong influence on stimulated C-peptide, which has to be taken into consideration when evaluating disease severity [23].

In type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is characterised by impaired beta cell function and insulin resistance, one study identified a unique plasma miRNA profile comprising ten miRNAs [33]. Interestingly, hsa-miR-197-3p was also found to correlate with impairments in glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes, as observed in the present study with type 1 diabetes mellitus. An elevated level of hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months in patients who completed follow-up at a diabetes duration of 5 years was associated with a sixfold increase in residual beta cell function, as assessed by stimulated C-peptide 12 months after diagnosis. This finding was replicated in the remaining study population of 83 children. Together, these findings suggest a role for hsa-miR-197-3p in beta cell function in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, some of the best validated target genes for hsa-miR197-3p, i.e. BMF and PMAIP1, are involved in the beta cell apoptosis pathways [34, 35]. Furthermore, hsa-miR-197-3p is involved in different immune pathways in other autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis [36], coeliac disease [37] and Graves’ disease [38], and in patients with the metabolic syndrome [39].

In the subgroup of the 40 children who participated at the 60 month visit, we found that stimulated C-peptide, IDAA1c and HbA1c at 6 and 12 months were predicted by hsa-miR-375, hsa-miR-301a-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-194-5p and hsa-miR-146a-5p levels at 3 months. Several reports have implicated these miRNAs in beta cell growth, development, differentiation and function [40–45]. These observations are in agreement with our findings; hsa-miR-375 levels were negatively associated with residual beta cell function 6 months after diagnosis, hsa-miR-24-3p indicated a better preserved beta cell function and/or insulin sensitivity 12 months after diagnosis, hsa-miR-146a-5p was associated with improved IDAA1c level after 12 months, and hsa-miR-194-5p was associated with a poorer IDAA1c level after 12 months. Whether these miRNAs reflect cell turnover (and if so, that of beta cells, insulin-dependent cells or immune cells) or result from the diabetic metabolic state cannot be deduced from the present study. We did not identify any miRNAs that predicted residual beta cell function at 60 months. This is likely because of the low degree of beta cell function remaining after 60 months (<10% of that at diagnosis), requiring a much larger sample size to detect a (small) difference. We were also not able to replicate our previous observation of hsa-miR-25 being a marker for residual beta cell function in the international Hvidoere cohort [13], possibly because of differences in the analytical platforms used in the two studies. However, in the present study, hsa-miR-25-3p was differentially expressed after diagnosis, suggesting a possible effect of disease progression on miRNA levels (unadjusted p = 0.0015, adjusted p = 0.16; data not shown). Thus, we cannot rule out an influence of hsa-miR-25-3p on disease development in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus.

The strengths of the present study are the phenotypically well-characterised cohort of children with new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus followed closely for the first 5 years after diagnosis with repeated measurements. A limitation of the study is the reduced number of individuals (40 patients) who completed the follow-up after a diabetes duration of 5 years, thus reducing the power to identify more predictive markers for beta cell function that may have had a smaller effect size. We only included those miRNAs that were identified in all samples during the normalisation analysis and, therefore, we cannot exclude the fact that miRNAs not fulfilling this stringent criterion may have predictive value. Another limitation is that, although the prospective study design enabled an analysis of associations between clinical characteristics and miRNAs, the observational feature makes the investigation of causality impossible.

In summary, this study suggests that hsa-miR-197-3p at 3 months can predict residual beta cell function 12 months after diagnosis. These findings may be of clinical relevance and could suggest new therapeutic avenues for intervention therapies, including miRNA-based patient stratification aimed at preserving and/or regenerating beta cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Abbreviations

- Cp :

-

Crossing point

- CLIP-seq:

-

Cross-linking, immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- IDAA1c :

-

Insulin-dose adjusted HbA1c

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- PANTHER:

-

Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationship

- RT-qPCR:

-

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

References

Esteller M (2011) Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet 12:861–874

Bartel DP (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215–233

Lai EC (2002) Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet 30:363–364

Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP (2010) Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466:835–840

Rottiers V, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F et al (2011) MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic diseases. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 76:225–233

Simpson LJ, Ansel KM (2015) MicroRNA regulation of lymphocyte tolerance and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest 125:2242–2249

Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO (2007) Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9:654–659

Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B (2011) Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39:7223–7233

Mathis D, Vence L, Benoist C (2001) beta-Cell death during progression to diabetes. Nature 414:792–798

Storling J, Overgaard AJ, Brorsson CA et al (2013) Do post-translational beta cell protein modifications trigger type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia 56:2347–2354

Melendez-Ramirez LY, Richards RJ, Cefalu WT (2010) Complications of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 39:625–640

Collares CV, Evangelista AF, Xavier DJ et al (2013) Identifying common and specific microRNAs expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cell of type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes mellitus patients. BMC Res Notes 6:491

Nielsen LB, Wang C, Sorensen K et al (2012) Circulating levels of microRNA from children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and healthy controls: evidence that miR-25 associates to residual beta-cell function and glycaemic control during disease progression. Exp Diabetes Res 2012:896362

Osmai M, Osmai Y, Bang-Berthelsen CH et al (2016) MicroRNAs as regulators of beta-cell function and dysfunction. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 32:334–349

Takahashi P, Xavier DJ, Evangelista AF et al (2014) MicroRNA expression profiling and functional annotation analysis of their targets in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gene 539:213–223

Chen YG, Cabrera SM, Jia S et al (2014) Molecular signatures differentiate immune states in type 1 diabetic families. Diabetes 63:3960–3973

Osipova J, Fischer DC, Dangwal S et al (2014) Diabetes-associated microRNAs in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E1661–E1665

Rajasekar P, O’Neill CL, Eeles L, Stitt AW, Medina RJ (2015) Epigenetic changes in endothelial progenitors as a possible cellular basis for glycemic memory in diabetic vascular complications. J Diabetes Res 2015:436879

Santovito D, De Nardis V, Marcantonio P et al (2014) Plasma exosome microRNA profiling unravels a new potential modulator of adiponectin pathway in diabetes: effect of glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E1681–E1685

Andersen ML, Rasmussen MA, Porksen S et al (2013) Complex multi-block analysis identifies new immunologic and genetic disease progression patterns associated with the residual beta-cell function 1 year after diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. PLoS One 8, e64632

Fredheim S, Andersen ML, Porksen S et al (2015) The influence of glucagon on postprandial hyperglycaemia in children 5 years after onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 58:828–834

Mortensen HB, Hougaard P, Swift P et al (2009) New definition for the partial remission period in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:1384–1390

Mortensen HB, Swift PG, Holl RW et al (2010) Multinational study in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes: association of age, ketoacidosis, HLA status, and autoantibodies on residual beta-cell function and glycemic control 12 months after diagnosis. Pediatr Diabetes 11:218–226

World Health Organization (1999) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation. Part 1. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Available from http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040. Accessed 1 April 2016

Blondal T, Jensby Nielsen S, Baker A et al (2013) Assessing sample and miRNA profile quality in serum and plasma or other biofluids. Methods 59:S1–S6

Mestdagh P, Van Vlierberghe P, De Weer A et al (2009) A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome Biol 10:R64

Hochberg Y (1988) A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75:800–802

Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N (2011) miRWalk–database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform 44:839–847

Chou CH, Chang NW, Shrestha S et al (2016) miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D239–D247

Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH, Yang JH (2014) starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D92–D97

Kanehisa M, Goto S (2000) KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28:27–30

Mi H, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD (2013) Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat Protoc 8:1551–1566

Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I et al (2010) Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ Res 107:810–817

Khoo C, Yang J, Weinrott SA et al (2012) Research resource: the pdx1 cistrome of pancreatic islets. Mol Endocrinol 26:521–533

Kilbride SM, Farrelly AM, Bonner C et al (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase mediates apoptosis in response to bioenergetic stress through activation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 homology domain-3-only protein BMF. J Biol Chem 285:36199–36206

Jernas M, Malmestrom C, Axelsson M et al (2013) MicroRNA regulate immune pathways in T cells in multiple sclerosis (MS). BMC Immunol 14:32

Magni S, Buoli Comani G, Elli L et al (2014) miRNAs affect the expression of innate and adaptive immunity proteins in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 109:1662–1674

Qin Q, Wang X, Yan N et al (2015) Aberrant expression of miRNA and mRNAs in lesioned tissues of Graves’ disease. Cell Physiol Biochem 35:1934–1942

Karolina DS, Tavintharan S, Armugam A et al (2012) Circulating miRNA profiles in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E2271–E2276

El Ouaamari A, Baroukh N, Martens GA, Lebrun P, Pipeleers D, van Obberghen E (2008) miR-375 targets 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 and regulates glucose-induced biological responses in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 57:2708–2717

Melkman-Zehavi T, Oren R, Kredo-Russo S et al (2011) miRNAs control insulin content in pancreatic beta-cells via downregulation of transcriptional repressors. EMBO J 30:835–845

Nathan G, Kredo-Russo S, Geiger T et al (2015) MiR-375 promotes redifferentiation of adult human beta cells expanded in vitro. PLoS One 10, e0122108

Norlin S, Ahlgren U, Edlund H (2005) Nuclear factor-{kappa}B activity in {beta}-cells is required for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 54:125–132

Poy MN, Hausser J, Trajkovski M et al (2009) miR-375 maintains normal pancreatic alpha- and beta-cell mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:5813–5818

Yu Y, Chai J, Zhang H et al (2014) miR-194 Promotes burn-induced hyperglycemia via attenuating IGF-IR expression. Shock 42:578–584

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following investigators for their efforts in executing this work: S. Pörksen (Paediatric Department, Roskilde Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark) for his contribution in outlining the protocol and collection of data for the Danish Remission Phase Cohort; M.-L. M. Andersen (Psychiatric Department for Children and Adolescents, Glostrup Hospital, Glostrup, Denmark) for recruiting patients for the follow-up study 5 years after diagnosis; and J. Svensson, J. Johannesen (Copenhagen Diabetes Research Center [CPH-DIRECT], Department of Paediatrics E, Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Herlev, Denmark and Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) and L. Hansen (CPH-DIRECT, Department of Paediatrics E, Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Herlev, Denmark) for their valuable contribution to critically revising the manuscript. Some of the data were presented as an abstract at the 51st Annual EASD Meeting in 2015, Stockholm, Sweden 2015 and at the 52nd Annual EASD Meeting in 2016, Munich, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was conducted with support from the Capital Region of Denmark’s Research Fund for Health Science, European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD-Novo Nordisk-JDRF), Beckett Foundation and Savværksejer Jeppe Juhl og hustru Ovita Juhls mindelegat. The study sponsor was not involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Duality of interest

All authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

LBN, HBM and FP contributed to the idea and the design of the study. NS, AHM, LBN, SK, HBM and FP researched the data and drafted, revised and edited the manuscript. PH performed the statistical analyses (except for Table 3, which was carried out by AHM and SK) and contributed to interpretation of the results and critical review of the manuscript. SF was responsible for acquisition of data, contributed to discussions, and reviewed and critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript to be published. FP is the guarantor of the manuscript and, as such, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(XLSX 454 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samandari, N., Mirza, A.H., Nielsen, L.B. et al. Circulating microRNA levels predict residual beta cell function and glycaemic control in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 60, 354–363 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4156-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4156-4