Abstract

Introduction

Patients with mental health problems in accident and emergency departments (A&E) are frequent users and often difficult to handle. Failure in managing these patients can cause adversities to both patients and A&E staff. It has been shown that nurse-based psychiatric consultation–liaison (CL) services work successfully and cost effectively in English-speaking countries, but they are hardly found in European countries. The aim of this study was to determine whether such a liaison service can be established in the A&E of a German general hospital. We describe structural and procedural elements of this service and present data of A&E patients who were referred to the newly established service during the first year of its existence, as well as an evaluation of this nurse-led service by non-psychiatric staff in the A&E and psychiatrists of the hospital’s department of psychiatry.

Subjects and methods

In 2008 a nurse-based psychiatric CL-service was introduced to the A&E of the Königin Elisabeth Herzberge (KEH) general hospital in the city of Berlin. Pathways for the nurse’s tasks were developed and patient-data collected from May 2008 till May 2009. An evaluation by questionnaire of attitudes towards the service of A&E staff and psychiatrists of the hospital’s psychiatric department was performed at the end of this period.

Results

Although limited by German law that many clinical decisions to be performed by physicians only, psychiatric CL-nurses can work successfully in an A&E if prepared by special training and supervised by a CL-psychiatrist. The evaluation of the service showed benefits with respect to satisfaction and skills of staff with regard to the management of psychiatrically ill patients.

Conclusion

Nurse-based psychiatric CL-services in A&E departments of general hospitals, originally developed in English-speaking countries, can be adapted for and implemented in a European country like Germany.

Open access: This article is published with open access at link.springer.com.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Patienten mit psychischen Problemen stellen sich häufig in der Notaufnahme vor, der Umgang mit ihnen ist schwierig. Misslingt die Versorgung dieser Patienten, kann dies für Patienten und Notaufnahmepersonal ungünstige Folgen haben. Es wurde in englischsprachigen Ländern nachgewiesen, dass ein psychiatrischer Konsiliardienst durch Krankenschwestern/-pfleger erfolgreich und wirtschaftlich arbeitet, aber ein solcher ist in europäischen Ländern kaum zu finden. Ziel der Studie war zu untersuchen, ob ein derartiger Konsiliardienst in der Notaufnahme eines deutschen Allgemeinkrankenhauses etabliert werden kann. Struktur- und Verfahrenskomponenten dieses Dienstes werden beschrieben, auch werden Daten über die Notfallpatienten, die im ersten Jahr seines Bestehens an den neu eingerichteten Dienst überwiesen wurden, sowie eine Beurteilung dieses von Pflegepersonal geleiteten Dienstes durch nichtpsychiatrisches Personal in der Notaufnahme und durch Psychiater der psychiatrischen Krankenhausabteilung dargelegt.

Probanden und Methoden

Im Jahr 2008 wurde ein von Pflegepersonal geführter psychiatrischer Konsiliardienst an der Notaufnahme des Allgemeinkrankenhauses „Königin Elisabeth Herzberge“ (KEH) in der Innenstadt von Berlin eingerichtet. Es wurden Vorgehensweisen für die Aufgaben des Pflegepersonals entwickelt und von Mai 2008 bis Mai 2009 Patientendaten dokumentiert. Am Ende dieses Zeitraums wurde eine Fragebogenuntersuchung zur Haltung des Personals der Notaufnahme und der Psychiater der psychiatrischen Krankenhausabteilung gegenüber diesem Dienst durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse

Auch wenn in Deutschland gesetzliche Beschränkungen bestehen, dass viele klinische Entscheidungen nur von einem Arzt getroffen werden dürfen, kann das Pflegepersonal eines psychiatrischen Konsiliardienstes erfolgreich in einer Notaufnahme arbeiten, wenn es durch eine spezielle Ausbildung vorbereitet wurde und unter der Aufsicht eines Psychiaters des Konsiliardienstes steht. Die Untersuchung dieses Dienstes ergab Vorteile im Hinblick auf Zufriedenheit und Fertigkeiten des Personals bei der Versorgung psychiatrisch erkrankter Patienten.

Schlussfolgerung

Von Pflegepersonal geführte psychiatrische Konsiliardienste in Notaufnahmen von Allgemeinkrankenhäusern, ein ursprünglich in englischsprachigen Ländern entwickeltes Konzept, können auf ein europäisches Land wie Deutschland zugeschnitten und dort etabliert werden.

Open access: Dieser Beitrag ist auf link.springer.com frei verfügbar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Patients with mental health problems in accident and emergency settings

Psychiatric comorbidity among patients in accident and emergency (A&E) settings is high and A&E staff is often not trained to deal with difficult and mentally ill patients. Hostile attitudes towards these patients may be a consequence and result in lower quality of health care as well as in high levels of distress among A&E staff [2, 3, 11]. Worldwide there is a great variability of ways how to manage patients with mental health problems in A&Es. In Germany, as in many other European countries apart from the United Kingdom (UK), there is neither a generally agreed upon model of care for psychiatrically ill patients presenting to A&E, nor are there valid data on the prevalence of mental disorders in such settings [10].

Models in English-speaking countries

In English-speaking countries like the UK, Australia and New Zealand as well as in the USA, CL-nurse-based models have a long tradition: In 1961 the UK Ministry of Health recommended that every patient attending the general hospital after a suicide attempt should be seen by a psychiatrist [4, 6], as a high risk of consecutively completed suicides was shown in A&E patients and cost effective solutions in order to provide appropriate care for this vulnerable group were mandated necessary [5, 8]. This was the starting point for the development of CL-nurse-based services. In the UK and Australia, nurses may even qualify for the status of Mental Health Practitioners (MHP) by which they become authorized to manage patients autonomously and even are allowed to prescribe a restricted choice of drugs by themselves [9, 12]. The safety of nurses’ assessments of psychiatric patients could be demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial [1].

One of the authors (RB) visited a well-established A&E mental health service in Leeds, UK, a city of about 750,000 inhabitants where a team of nurses provides 24-h/7-day coverage for the city’s two busy A&Es. Such services have become usual in the UK for two reasons: (1) because of the government target that 98 % of all patients attending A&E should be assessed, treated and discharged within 4 h of arrival at A&E and (2) because of the policy of reducing psychiatric inpatient beds, A&E nurses were supposed to help avoid unnecessary hospital admissions.

A comparable nurse-led service in Australia, as described by McDonough et al. [7] led to a reduction of about 90 % in patients’ waiting time in the A&E and a reduction of the percentage of patients leaving without a care plan. On the A&E staff’s side there was an overall satisfaction with the CL-nurses work and a sense of having improved their own skills in managing difficult patients by way of interdisciplinary cooperation; the CL-nurses as well reported that they had improved their skills and enhanced their professional self-esteem.

Legal issues are different between countries: In Germany, with very few exceptions (e.g. Thomas Wagner, Ludwig-Noll-Hospital in Kassel, State of Hesse, personal communication 2009) the overall responsibility for assessment and treatment of self-harm patients is restricted to physicians. With respect to the A&E settings in Germany this means that a psychiatric CL-nurse would have to cooperate very closely with a psychiatrist as all legally relevant decisions have to be made by a physician.

Psychiatric care situation of patients presenting to the A&E department

While in 2003, 14,800 patients presented to the A&E of the hospital Königin Elisabeth Herzberge (KEH) in Berlin, in 2007 this number had increased to 16,650, resulting in growing numbers of patients referred to the hospital’s psychiatric CL-service, equivalent to a referral rate of about 20 % at both points of time. Until 2007 one fulltime CL-psychiatrist was responsible for all consultations in the A&E as well as in the other general hospital departments (900 annual referrals) during office hours (8 a.m.–4 p.m.). In addition, she/he was responsible for the “telephone hotline” which is used by private practice and primary care physicians who want to admit patients to the psychiatric wards, as well as by patients and their relatives who ask for information about treatment options in the KEH. Between 4 p.m. and 8 a.m. psychiatrists on duty from the psychiatric department were responsible for all consultations. If the CL-psychiatrist was not able to manage the number of consultations, he received support by other physicians from the psychiatric wards. Frequently, this led to delays for patients in the A&E, as well as to disturbances of the daily work routine on the wards. As a consequence of the growing numbers of mentally ill patients in the A&E which led to an increased workload not only for the CL-psychiatrist but for the psychiatrists from the psychiatric wards as well, alternative ways of psychiatric care for the A&E had to be developed and it was decided to study the implementation a nurse-based psychiatric CL-service in 2008 drawing heavily from the Leeds (UK) service model.

Study aims

The aims of our study were the following:

-

to investigate if it is feasible to implement a nurse-based psychiatric CL-service in the A&E of a general hospital in Germany, and which tasks can be taken over by a CL-nurse given the legal limitations mentioned above,

-

to investigate the main pathways of care of A&E patients who were referred to the nurse-based psychiatric CL-service during its implementation period from May 2008 to May 2009 and

-

to evaluate effects and acceptance of such a nurse-led service by A&E staff and by psychiatrists of the hospital’s psychiatric department.

Subjects and methods

Description of the KEH A&E department

The general hospital KEH is situated in the north east of Berlin. It is a university-affiliated hospital of the Charité Berlin and serves an inner city area with about 220,000 inhabitants. It has 300 somatic hospital beds (e.g. internal medicine, general surgery and neurology) and 130 psychiatric beds and two psychiatric day-treatment centres. The A&E is managed by the Department of Internal Medicine with an on-call psychiatric CL-service. Triage and referral to the psychiatric CL-service is performed by an A&E staff internist and by A&E staff nurses.

From May 2008 to May 2009, for all patients referred to the psychiatric CL-service psychiatric diagnoses, times and pathways of presentation to A&E as well as CL-psychiatric recommendations for treatment after discharge from A&E were documented by the CL-service with the hospital’s documentation system Nexus/Medicare®.

Training of the CL-nurse and implementation of the liaison service

A nurse with over 10 years of psychiatric experience (RG) was chosen from the psychiatric department’s nursing staff for the newly established function fulfilling as prerequisite a strong interest in issues of psychiatric and somatic comorbidity, and in working with an interdisciplinary team of somatic physicians and nurses. This nurse then received

-

two months of “training-on-the-job”, working as a general nurse within the A&E team and

-

two months of intensive “bed side” teaching and supervision provided by a senior CL-psychiatrist (RB), covering as many aspects of the A&E and CL-psychiatric setting as possible.

This “training period” was also used to work out pathways for the CL-nurse’s service. This meant for example that

-

pathways for answering to physicians who called the “telephone hotline” and to provide information to patients and relatives,

-

pathways of communication for referrals from the A&E to the psychiatric wards,

-

pathways of care to and communication with primary care physicians and community mental health services and

-

all of these CL-nurses activities where carefully discussed and checked with the head nurse on an ongoing basis to meet German legal requirements for nursing activities before being put into operation.

In May 2008 the nurse-based psychiatric CL-service started working in the A&E on weekdays from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Its fields of activity are described in the Results Section below.

Evaluation of the CL-nurse-based service

In May 2009, 1 year after its implementation, the attitudes of A&E staff and psychiatrists collaborating with the CL-nurse towards the newly implemented nurse-based service were evaluated by a questionnaire and statistically analyzed. The questionnaire covered the following topics:

-

Is this nurse-based psychiatric CL-service helpful for your daily work routine? [numeric analogue scale (NAS) from 1 (very helpful) –5 (not helpful at all)]

-

Please check any of the following activities that you feel are helpful

-

General management of patients

-

Psychiatric assessment performed by the CL-nurse

-

Talking down agitated or anxious patients

-

Assist agitated or anxious patients with somatic comorbidity through A&E assessment and treatment

-

Taking ECG

-

Taking blood samples

-

Time savings in general

-

-

Did you feel there were any activities of the CL-nurse that were not helpful (checklist)

-

Disagreements how to manage a patient

-

Redundant questions to patients

-

-

In addition, there was the possibility of comments to be given in free text.

In addition, A&E staff nurses and doctors were asked the two following questions:

-

Has the nurse-based psychiatric CL-service had an impact on your knowledge and skills in handling “difficult” patients (Yes/No)

-

If yes, by which way(s) did you learn these skills:

-

Joint case discussions

-

Training courses

-

Learning from the CL-nurse as a role model

-

Where appropriate, descriptive statistics were performed by using SPSS 15.0.

Results

Responsibilities of the CL-nurse

The CL-nurse took over the following tasks:

-

During office hours every A&E patient who required psychiatric consultation was seen by the nurse. She made the first psychiatric approach by offering help or de-escalating difficult situations. She took the patient’s history and checked for medical notes and reports. Then she presented results and the patient to the psychiatrist on duty. After the psychiatrist saw the patient, both made a joint decision about the patient’s further management. She took blood samples and performed ECG when indicated. Whenever a patient was psychotic or very anxious she tried to talk him down and, if necessary, accompanied him on his way to the psychiatric ward.

-

Managing the telephone hotline for questions from health care providers, patients and families from outside the hospital was one of the most time-consuming and complex tasks of the CL-nurse, especially with regard to being the first contact for referring physicians. In addition she counselled and gave information about the hospital’s services to patients and relatives. With regard to questions and referrals she was not able to handle by herself, pathways were developed in consensus with staff from the psychiatric department.

-

On the rare occasions when there was no psychiatric patient to be assessed or cared for in the A&E, the CL-nurse took part in the regular CL-work on the general hospital wards:

-

counselling for patients with substance misuse problems,

-

performing cognitive screening tests in dementia patients,

-

offering relaxation therapies for somatically ill and distressed patients and

-

giving advice and support to general hospital nurses in managing difficult or mentally ill patients.

-

-

The CL-nurse helped with the registration of A&E patients seen by the psychiatric CL-service in the hospital’s documentation system.

-

The CL-nurse occasionally gave training sessions for her A&E general nurse colleagues, for example about de-escalation and how to deal with aggressive and violent patients. Most importantly she provided a role model for positive attitudes towards and communication with mentally ill patients presenting to the A&E.

Throughout, responsibility for clinical decisions like hospital admission vs. discharge from A&E, further diagnostic action or prescription of medication was restricted to the psychiatrists.

Referral of A&E patients for CL-services

During the evaluation period between 01 May 2008 and 01 May 2009 about 18,100 patients presented themselves to the KEH A&E, and 3784 (21 %) of them were referred to the psychiatric CL-service. The most common psychiatric diagnoses seen were substance use related problems, particularly men with alcohol problems. With regard to ICD-10 F3x diagnoses, women were predominant, whereas in organic–psychiatric disorders genders were equally distributed (Fig. 1).

About 43 % of patients presented themselves during the CL-nurse’s regular office hours between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. The remainder of patients (34 %) arrived between 4 p.m. and 10 p.m., 22 % between 10 p.m. and 8 a.m. Most of the patients presented themselves without referral by a primary care physician, a large proportion of whom was brought by emergency ambulance and by police, which underlines the urgency of their reason for visit (Fig. 2).

About one half of the patients were admitted to the psychiatric department for inpatient treatment, much fewer to the KEH’s general hospital wards (4 %). More than a third was discharged from the A&E into outpatient treatment after having been evaluated by the CL-service. In most of these cases, the primary care physicians or psychiatrists in private practice were contacted before discharge by telephone. The remaining patients were referred to other hospitals, received a scheduled appointment for admission to the psychiatric department of the KEH, or left unnoticed (Fig. 3).

Evaluation of the CL-service

In May 2009 questionnaires were given to psychiatrists (n = 28) and A&E staff (physicians and nurses, n = 21). The response rate was 80 %. Twenty psychiatrists and 15 members of A&E staff completed the questionnaires. In all, 95 % of psychiatrists and 100 % of A&E staff rated the service also as “helpful” or “very helpful”.

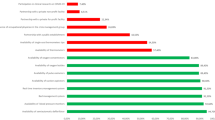

The majority of psychiatrists and A&E staff reported that the CL-nurse helped to reduce their workload: time-consuming telephone calls of psychiatrists were taken over by the nurse, and attending psychiatrists reported time savings for their assessments of patients, i.e. by not having to search for clinical notes and laboratory test results. With the exception of two psychiatrists, who mentioned “disagreements in managing patients” and “redundant questions to patients” as a problem, no further disadvantages of the CL-nurse’s service were specified by psychiatrists and A&E staff. “Help with managing patients”, in general, and “capacity to talk down and to establish a relationship with patients” and “de-escalate difficult situations”, in particular, were mentioned as helpful (Fig. 4).

When asked about any influence on their own skills in dealing with difficult and mentally ill patients, 90 % of the A&E nurses (n = 10) and 25 % of the somatic doctors (n = 1) rated their skills as improved. In addition, 77 % of the A&E nurses (n = 8) felt that their skills had improved by having joint case discussions and 45 % (n = 5) felt that they had learned from the CL-nurse as a role model (Fig. 5).

Discussion

One year after a nurse-based psychiatric CL-service was established in the A&E of an inner city general hospital in Germany, its implementation was judged as feasible and successful by A&E staff and psychiatrists of the hospital. Our results are in line with the literature on successful psychiatric CL-nurse-based A&E services in English-speaking countries [7, 12]. Of note, the emergency setting in which our service was established showed a referral rate of 20 % of A&E patients to psychiatry which is high in comparison to an estimated prevalence of 7 % of mental disorders in A&E settings as reported in the literature [10]. The following positive effects of the newly established service were described by A&E staff and hospital psychiatrists:

-

Psychiatrists and A&E staff felt that the service of the CL-nurse resulted in time savings. The majority of psychiatrists including the regular CL-psychiatrist reported reduced workloads. A&E staff, not trained to deal with behaviourally disturbed acutely ill patients, reported time savings and an improvement in their skills of managing such patients.

-

Although the attitudes of A&E patients towards the CL-nurse were not studied systematically, positive responses from a majority of patients were noted. The service seemed to have a positive influence on the climate on the psychiatric wards, where the patients referred from A&E were better prepared for admission.

-

During the observational period there were no legal issues concerning the responsibilities of the CL-nurse.

What were the problems we faced?

-

Many patients with psychiatric problems attend A&E during the late afternoon and night shift. It was not possible to obtain hospital funding for another CL-nurse to cover this period, as well as e.g. holidays or sick leave of the CL-nurse.

-

Our nurse-based “hotline telephone service” for psychiatric admissions and counselling was mostly, but not always accepted by referring physicians, who sometimes preferred to talk to a psychiatrist only,

What are the skills needed by a CL-nurse?

-

Experience: nurses with more than 5 years’ experience with psychiatric inpatients, especially with patients with psychosis and comorbid substance abuse can be recommended.

-

Interdisciplinary interest: She or he should have an interest in cooperation with other medical specialties and other staff members as well as medical knowledge. General hospital nursing knowledge would be in particular helpful to work as mental health professional in a general hospital department.

-

Communication skills: a CL-nurse in A&E should have good communication skills and be accepted by the A&E nurses. But she or he should be able to stand their ground in case of disagreements or disputes between psychiatric and other hospital staff.

Limitations of the study

This is a single-site observational study with a cross-sectional analysis of attitudes of hospital staff towards the implementation of a new CL-service in a general hospital A&E department. Satisfaction of patients and referring primary care physicians with the new service was not studied due to limited resources. The study population (A&E staff and physicians of the psychiatric department) is rather small and may not be representative for other settings. We did not analyze cost savings due to our model, which we think can be expected as psychiatric nurses are less expensive than CL-psychiatrists. Of note, in 2009 the administration of KEH hospital decided to continue the nurse-based psychiatric CL-service beyond its implementation period.

Conclusion

The activities of mental health professionals working in the A&E of a general hospital are manifold. Not all psychiatric tasks must be performed by a psychiatrist. Quite an array can be carried out by a qualified psychiatric CL-nurse, e.g. establishing a relationship with patients and de-escalating difficult situations. Our study shows that a CL-nurse can play a major role in the assessment and management of patients with mental health problems in the A&E, even if certain clinical decisions and duties have to be performed by psychiatrists for legal reasons. This leads to an improvement of nonpsychiatric staff’s attitudes and skills with regard to psychiatrically ill patients. We conclude that a CL-service model based on psychiatric nurses, as being part of everyday hospital routine in countries such as the UK and Australia for a long time, can also be successfully implemented in Germany. Further research is warranted to investigate whether our model of a nurse-based psychiatric CL-service can be implemented in other hospitals in Germany and whether such models lead to cost savings as compared to traditional CL-services that rely on psychiatrists only.

References

Catalan J, Marsack P, Hawton KE et al (1980) Comparison of doctors and nurses in the assessment of deliberate self-poisoning patients. Psychol Med 10:483–491

Crawford T, Geraghty W et al (2003) Staff knowledge and attitudes toward deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J Adolesc 26:619–629

Creed F, Pfeffer J (1981) Attitudes of house physicians toward self-poisoning patients. Med Educ 15:340–345

Diefenbacher A, Rothermundt M, Arolt V (2004) Aufgaben der Konsiliarpsychiatrie und -psychotherapie. In: Arolt V, Diefenbacher A (eds) Psychiatrie in der klinischen Medizin. Steinkopff, Darmstadt, pp 3–18

Gardner R, Hanka R et al (1982) Psychological and social evaluation in cases of deliberate self poisoning seen in an accident department. BMJ 284:491–493

Mayou R (1989) The history of general hospital psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 155:764–766

McDonough S, Wynaden D et al (2004) Emergency department mental health triage consultancy service: an evaluation of the first year of the service. Accid Emerg Nurs 121:31–38

Ryan JM, Rhusdy A, Perez-Avila CA (1996) Suicide following attendance at an accident and emergency department with deliberate self harm. J Accid Emerg Med 13:101–104

Patel MX, Robson D et al (2009) Attitudes regarding metal health nurse prescribing among psychiatrists and nurses: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Nurs Stud 46:1467–1474

Puffer E, Messer T, Panjonk FG (2012) Psychiatric care in emergency departments. Anaesthesist 61:215–223

Suokas J, Suominen K, Lönnqvist J (2009) The attitudes of emergency staff toward attempted suicide patients. A comparative study before and after establishment of a Psychiatric Consultation Service. Crisis 30:161–165

Wand T, Fisher J (2006) The mental health nurse practitioner in the emergency department: an Australian experience. Int J Ment Health Nurs 15:201–208

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. rer.nat. C. Grubich, J. König, Dr. med. R. Asche, R. Korzendorfer, U. Kropp, the members of the KEH A&E staff and the physicians of the psychiatric department for supporting the project and the study. We would also like to thank Manja Elle for supporting the publication process.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Conflict of interest. R. Burian, D. Protheroe, R. Gunrow, and A. Diefenbacher state that there are no conflicts of interest. The accompanying manuscript does not include studies on humans or animals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burian, R., Protheroe, D., Grunow, R. et al. Establishing a nurse-based psychiatric CL service in the accident and emergency department of a general hospital in Germany. Nervenarzt 85, 1217–1224 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-014-4069-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-014-4069-8

Keywords

- Consultation–liaison psychiatry

- Mental health nurses

- Emergency psychiatry

- Emergency services, hospital

- General hospital psychiatry