Abstract

A novel solar-two-step thermochemical concept for continuous production of H\(_2\) or CO from solar energy and H\(_2\)O or CO\(_2\) using the redox pair MOFe\(_2\)O\(_3\)/MO as reactive particles is proposed and assessed. Here, an efficient continuous separation mechanism is devised by the use of an external magnetic field and the weak magnetization of MOFe\(_2\)O\(_3\) at the working temperatures. The mechanism is suitable for systems of ferrites with a Curie temperature in the range 500–800 \(^{\circ }\)C where water or CO\(_2\) decomposition occurs. One of the most promising candidates is the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO system. Pyromagnetic coefficients for Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) were obtained experimentally. A simple magnetic trap was employed and the separation ratios Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO were obtained. The results are encouraging and motivate the development of full-scale solar reactor prototypes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite thermolysis being the most direct, one-step process for splitting molecules, it is neither practical nor efficient in the case of either H\(_2\)O or CO\(_2\) for the production of H\(_2\) and CO in solar reactors, because it requires a very high temperature (>2500 \(^{\circ }\)C) to obtain a significant dissociation fraction [1], resulting in problems with losses due to vigorous product recombination, reactor material limitations, and excessive aperture radiation losses when concentrated solar heat is used.

The need for extremely high temperatures has been alleviated by the use of thermochemical cycles, in which the thermolysis step is broken down into two or more reactions, while the overall process remains that of splitting H\(_2\)O or CO\(_2\). As far as the authors know, the usage of solar heat to run a two-step cycle was first proposed in 1977 by Nakamura [2], considering the redox pair Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO. Since then, the list of suitable redox pairs has grown considerably, consisting of oxide pairs of multivalent metal oxides. Among the candidate pairs are: iron oxide Fe3O4/FeO [2, 3], manganese oxide Mn\(_3\)O\(_4\)/MnO [4], cerium oxide CeO\(_2\)/Ce\(_2\)O\(_3\) [5], ferrites [6–9], or metal oxide/metal pairs, such as zinc oxide/zinc ZnO/Zn [10, 11], just to name a few.

The basis behind the two-step thermochemical cycle can be summarized in the following set of reactions:

First step: thermal reduction

Second step: thermal oxidation

Water splitting

or

\(CO_2\) splitting

where water decomposition occurs at low temperatures in the range 500–800 \(^{\circ }\)C by reacting with the reduced form of the oxide M\(_x\)O\(_y\), leading to the formation of the oxide M\(_x\)O\(_{y+z}\) and H\(_2\) or CO. With particular application to the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO system, the previous set of redox reactions becomes:

First step: thermal reduction

and

Second step: thermal oxidation

Water splitting

or

\(CO_2\) splitting

However, as a direct result of the two-step cycle, some problems arise. These are discussed below.

Problem statement

From Eqs. 5 and 6 for water and CO\(_2\) oxidation, respectively, the reaction temperature must be optimized. Thermodynamics favor low reaction temperatures, but the kinetics need to be sufficiently fast for practical purposes and thus prohibit temperatures that are too low. Therefore, the entire process (thermal reduction and water oxidation) is carried out using a temperature swing operation with a temperature difference of about 400 K [12]. In parallel to this, the gaseous feed to the metal oxide has to swing between steam and inert purge gas.

A number of process and reactor concepts have been proposed to achieve such a temperature swing [12]. They can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

systems based on transporting metal oxide particles in the form of fluidized beds or moving beds [12–14], where particles are conveyed from hotter sections of the reactors where thermal reduction takes place to colder sections to allow water oxidation to take place, and returned after completion;

-

2.

designs suggesting achieving this by using monolithic porous structures made of the active metal oxides and turning or moving them, such that they alternately move through the hot and cold sections [15, 16]; and

-

3.

designs suggesting fixing the metal oxide and raising/lowering the solar heat flux by focusing/defocusing the mirrors [17, 18].

However, as will be discussed in this paper, there is an alternative, interesting possibility in the application of ferrite systems, with special reference to the prominent Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO system, by harnessing the intrinsic magnetic properties of ferrites. This possibility has not until now been explored, but offers the attractive possibility of a truly continuous phase separation process that circumvents the need for the movable parts of the current approaches. The key point for the feasibility of magnetic separation lies in the high Curie temperature of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\), which is just within the range for thermochemical thermal oxidation (the second step). Then, under the action of an external magnetic field, some weak magnetization of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) can be achieved, which allows the possibility of self-separation from the non-magnetic FeO component.

The magnetic properties of ferrites

Ferrites, with the general formula MO\(\cdot \)Fe\(_2\)O\(_3\), where M stands for Fe, Mn, Ni, Cu, or Mg, exhibit ferrimagnetism. In ferrimagnetism, the net moment is smaller than in a typical ferromagnetic material, although the macroscopic magnetic characteristics of ferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism are similar. In such ferrimagnetic materials, the opposing magnetic moments are unequal and thus a spontaneous magnetization remains (see Fig. 1). However, ferrimagnetic ordering disappears at the Curie temperature \(\Theta \). Beyond this temperature, the material behaves as a paramagnetic material due to the tendency of molecular moments to align with the applied magnetic field, but in the absence of long-range order. Magnetite, which has the composition Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\), is the best-known ferrite with a Curie temperature of 850 K. In contrast, antiferromagnetic materials present no net magnetic moment at any temperature. Antiferromagnetism is a property of MnO, FeO, NiO, and many other compounds. The antiferromagnetic ordering disappears at the critical Néel temperature, which for FeO is 198 K.

As previously discussed, in a two-step thermochemical cycle, water decomposition can take place in the temperature range 500–800 \(^{\circ }\)C [19]. In this temperature range, FeO is clearly non-magnetic, but Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) could exhibit ferrimagnetic behavior with a net magnetic moment owing to its high Curie temperature. Thus, it is conceivable that magnetic separation between Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) and FeO is at least theoretically feasible.

First, let us consider the magnetic behavior of magnetite (Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)) close to its Curie temperature, which is where our interest is focused. Near the Curie temperature \(\Theta \), a linear equation of state can be assumed as a first approximation for the magnetization of a ferromagnetic/ferrimagnetic material [20], and then magnetization can be expressed as:

where \(\Theta \) is the Curie temperature and

is the so-called pyromagnetic coefficient. On the other hand, the magnetic force acting on a magnetic particle with magnetization M is given by [20]:

where \(\mu _0=4\pi \times 10^{-7}\) H m\(^{-1}\) is the vacuum permeability, \(V=\frac{\pi D^3}{6}\) is the volume for a spherical particle of diameter D, and \(\frac{dH}{dl}\) is the gradient of the magnetic field. Inserting Eq. 7 into Eq. 9 yields:

The gravitational force acting indiscriminately on magnetic and non-magnetic particles, i.e. Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) and FeO particles, is given by:

where g is the gravitational acceleration and \(\rho \) the particle density.

Hence, if the magnetic force acting on the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles is to overcome gravitational settling, i.e. \(F_\mathrm{mag} \ge F_g\), then, taking into account Eqs. 10 and 11, we require that:

Results and discussion

We sought to verify these theoretical predictions experimentally. The experiment, although rather simple, is nevertheless worthwhile, because if it successfully demonstrates the feasibility of obtaining a mechanism of separation without any sophisticated devices or equipment, this will provide encouragement to the scientific community to carry out full-scale simulations of the concept in solar reactors.

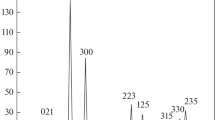

Experimental measurements of the pyromagnetic coefficients for Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) close to the Curie temperatures were provided by AGICO (Advanced Geoscience Instruments Company) situated in Brno, Czech Republic. AGICO is one of the most respected world producers of scientific instruments for measuring rock magnetism, palaeomagnetism, and environmental magnetism. The experimental data were obtained using the AGICO (ex-Geofyzika Brno) Kapabridges magnetic susceptibility meter (KLY-2 and KLY-3 models) for samples of pure Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\). Representative results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Knowledge of the pyromagnetic coefficient allows us to work in the laboratory at lower temperatures, which for a first evaluation of the concept seems preferable. A rather simple device was designed to test the technical feasibility of magnetic separation in an FeO–Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) system, using a “magnetic bottle” or “magnetic trap”. The model consisted of a magnetic bottle divided into top and bottom chambers, which looks rather like an hourglass (see Figs. 4 and 5). The bottle was made of borosilicate glass, and the magnetic gradient was generated by a conical solenoid placed in its neck.

Using this device a mixture of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) and FeO was initially placed in the top chamber, where the sample was heated up to 250 \(^\circ \)C by using a Berner hot air blower (model BHAB 2300 E) and, to promote the separation of phases, an alternating current was used and the current was regulated to produce the desired magnetic gradient.

The physics behind this simple device is easy to grasp, observing Fig. 4, and can be summarized as follows: under the influence of the external magnetic and gravitational fields, only the non-magnetic (i.e. FeO) particles are able to pass through the narrow neck of the bottle and fall into the bottom chamber, while the magnetized Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles are trapped in the top chamber.

The use of an alternating current, rather than direct current, was mainly motivated by a desire to take advantage of the strong “up–down shaking” promoted by the oscillating magnetic field on the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles, which prevents “particle clogging” in the small cavity located at the bottle neck and makes it easier for the FeO particles to fall into the bottom chamber under the action of gravity.

To prevent the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles escaping towards the bottom chamber when the magnetic field is temporarily boosting the gravitational field, i.e. when they are both downward directed, it is necessary to select a suitable frequency for the alternating current. The minimum suitable frequency can be estimated from the following considerations:

The total force acting on the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles is given by:

where \(\vec {F}_g\) and \(\vec {F}_\mathrm{mag}\) are the gravitational and magnetic forces, respectively, and the “\(\pm \)” symbol reflects the fact that the magnetic field is oscillating up (\(-\)) and down (\(+\)) because of its alternating nature. In contrast, the net force acting on the FeO is due only to the action of gravity:

According to Eq. 13, there will be times when the magnetic force will be in the same direction as the gravitational force. To prevent Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles crossing the small cavity between the top and bottom chambers, the maximum displacement of the magnetic particles during the combined effect of these forces must be less than the characteristic length of the cavity, or mathematically:

where \(m = \rho V\) is the particle mass, t the time for which the magnetic field is in the same direction as the gravitational field, and \(l_c\) the characteristic length of the cavity. Considering Eqs. 14, 11 and 10, and noting that the frequency is given by \(f=\frac{1}{2t}\), we have:

Taking into account the dimensions of the chamber with \(l_c\approx 2\) cm and with magnetic gradients of \(2\times 10^5\) A m\(^{-2}\) generated, Eq. 16 predicts that frequencies at least as high as 75 Hz are needed if leakage of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles to the bottom chamber is to be prevented.

Recall that the use of an alternating current in our experiment was proposed because the generation of vigorous magnetic agitation or “shaking” would help prevent clogging of the neck of the bottle, and thus ease the passage of FeO particles to the bottom chamber under gravity. However, any other mechanism for preventing clogging, e.g. induced vibrations, could be used instead, and, in such a case, a direct current could be used to generate the magnetic field. To minimize the likelihood of clogging, an alternating current frequency used in our experiments was 150 Hz, i.e. twice the minimum value estimated.

The linear magnetic field gradient was produced using a solenoid with conical geometry along the axis of the desired gradient (see Figs. 4, 5). Assume a solenoid of length l, radii \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) at the respective ends, and N windings with a current I. With the center of the cone at \(z=r=0\) such that the ends are at \(z=\pm \frac{l}{2}\), respectively, and \(r_o=r(z=0)=\frac{r_1+r_2}{2}\), with an operating angle \(\alpha \) given by \(\alpha =\tan ^{-1}(\frac{r_2-r_1}{l})\) (see Fig. 6), from the Biot–Savart law for the on-axis field of N current loops, we obtain:

and the magnetic field gradient is given by:

The temperature was limited to 250 \(^\circ \)C to provide an adequate margin from the working temperature limit of borosilicate glass of 500 \(^\circ \)C. However, through knowledge of the pyromagnetic constant, it is possible to determine the behavior of magnetic particles at higher temperatures. From Eqs. 9 and 7, an effective magnetic gradient may be defined as:

where \(T_0\) is the working temperature (250 \(^\circ \)C in our case) and T is the temperature at which we want to know the magnetic behavior of the particle. So, as first approximation, a magnetic particle at temperature T will have the same magnetic behavior as a particle at temperature \(T_0,\) but with an effective magnetic gradient given by Eq. 19.

Finally, separation ratios were defined for the top and bottom chambers. For the top chamber, where Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles will be magnetically trapped, the separation ratio is given by:

where \(c^t_{\text {Fe}_3\text {O}_4}\) and \(c^t_{\text {FeO}}\) are the concentrations of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) and FeO in the top chamber. Similarly, the separation ratio for the bottom chamber, where the non-magnetic FeO particles are settling under gravity, is given by:

where \(c^b_{\text {FeO}}\) and \(c^b_{\text {Fe}_3\text {O}_4}\) are the concentrations of FeO and Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) in the bottom chamber.

Figures 7, 8 and 9 show predicted separation ratios as a function of temperature for various values of the magnetic field gradient based on our measurements at 250 \(^\circ \)C. These show that with sufficiently high magnetic field gradients (>2.5\(\,\times \,10^6\) A m\(^{-2}\)) separation ratios in excess of 0.8 can be achieved in both chambers at working temperatures of 600 K and, for higher magnetic gradients, at 700 K.

It is interesting to observe that the additional magnetic shaking promoted by the magnetic field can result in an efficient oxygen-removal mechanism in Eq. 4 and then favor the thermochemical conversion and production of H\(_2\) or CO by shifting the equilibrium of the reaction to the right. Ultimately, this efficiency gain can result in a reduction in oxide heating and associated losses, because less oxide must be heated to produce the same amount of H\(_2\) [23]. A number of methods have been proposed to decrease the oxygen thermal reduction pressure in the chamber, such as, for example, evacuation via vacuum pumping or decreasing the oxygen thermal reduction pressure via inert gas sweeping [10, 15, 21–23]. Thus, thanks to the additional magnetic agitation, the use of vacuum pumps or gas sweeping is at least reduced, if not eliminated.

Finally, it is worth assessing the feasibility of magnetic separation if we are working above the Curie temperature. Above the Curie point, ferrite is paramagnetic. Thus, the magnetization M follows the Curie law:

where \(M_\mathrm{s}\) is the magnetization at saturation, \(L(\alpha )\) denotes the Langevin function, and for magnetite \(\alpha \), the ratio of the Zeeman energy of the magnetic moment to the thermal energy, is given by:

where \(\mu _{\text {B}}\) is the Bohr magneton and k is the Boltzmann constant.

Figure 10 shows a plot of the relationship given by Eq. 22. We can estimate the expected value of \(\alpha \) under normal laboratory conditions. With a typical electromagnet producing a field of, say, 0.5 T, and \(T= 850\) K, we get \(\alpha \approx 1.0\times 10^{-3}\). Thus, looking at Fig. 10 we can see that for such small values of \(\alpha \), M will be a very small fraction of the saturation value \(M_\mathrm{s}\), making magnetic separation at such a temperature (above the Curie point) impractical.

Conclusions

Magnetic separation of phases for a ferrite (MOFe\(_2\)O\(_3\)/MO) system during water or CO\(_2\) decomposition in a two-step solar thermochemical cycle is technically feasible, if the ferrite compound has a Curie temperature in the range 773–1073 K where water or CO\(_2\) decomposition occurs. The redox pair Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\)/FeO, with a Curie temperature of 858 K for Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\), is a prominent potential candidate.

The additional vigorous magnetic shaking promoted by the use of an alternating magnetic field can result in an efficient oxygen-removal mechanism favoring the thermochemical conversion process and reducing requirements for the use of vacuum pumps or inert gas sweeping.

Experimental data were obtained for the pyromagnetic coefficients of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\). Experiments conducted at 250 \(^\circ \)C lead us to predict that a high effectiveness for magnetic-gravitational separation between Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) and FeO can be achieved at temperatures of interest.

Additional research and development are required to test magnetic separation in ferrites using a full-scale solar reactor.

Abbreviations

- B :

-

Flux density

- c :

-

Concentration

- D :

-

Particle diameter

- E :

-

Energy

- f :

-

Frequency

- F :

-

Force

- g :

-

Gravitational acceleration

- H :

-

Magnetic field strength

- I :

-

Current

- k :

-

Boltzmann constant

- K :

-

Pyromagnetic coefficient

- l :

-

Length

- m :

-

Mass of particle

- M :

-

Magnetization

- N :

-

Number of windings

- r :

-

Radial distance

- t :

-

Time

- S :

-

Separation ratio

- T :

-

Temperature

- V :

-

Volume of particle

- z :

-

Axial coordinate

- \(\alpha \) :

-

Ratio of Zeeman energy to thermal energy

- \(\mu _0\) :

-

Vacuum permeability

- \(\mu _{\text {B}}\) :

-

Bohr magneton

- \(\rho \) :

-

Density particle

- \(\Theta \) :

-

Curie temperature

- c :

-

Cavity

- dd :

-

dipole–dipole

- g :

-

Gravitational

- mag :

-

Magnetic

- b :

-

Bottom

- t :

-

Top

References

Fletcher, E.A., Moen, R.L.: Hydrogen and oxygen from water. Science. 197, 1050–1056 (1977)

Nakamura, T.: Hydrogen production from water utilizing solar heat at high temperatures. Sol. Energy. 19, 467–475 (1977)

Charvin, P., Abanades, S., Flamant, G., Lemort, F.: Two-step water splitting thermochemical cycle based on iron oxide redox pair for solar hydrogen production. Energy. 32, 1124–1133 (2007)

Sturzenegger, M., Nüesch, P.: Efficiency analysis for a manganese-oxide-based thermochemical cycle. Energy. 24, 959–970 (1999)

Abanades, S., Flamant, G.: Thermochemical hydrogen production from a two-step solar-driven water-splitting cycle based on cerium oxides. Sol. Energy. 80, 1611–1623 (2006)

Tamaura, Y., Kojima, M., Sano, T., Ueda, Y., Hasegawa, N., Tsuji, M.: Thermodynamic evaluation of water splitting by a cation-excessive (Ni, Mn) ferrite. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 23, 1185–1191 (1998)

Agrafiotis, C., Roeb, M., Konstandopoulos, A.G., Nalbandian, L., Zaspalis, V.T., Sattler, C., Stobbe, P., Steele, A.M.: Solar water splitting for hydrogen production with monolithic reactors. Sol. Energy. 79, 409–421 (2005)

Miller, J.E., Evans, L.R., Stuecker, J.N., Allendorf, M.D., Siegel, N.P., Diver, R.B.: Materials development for the CR5 solar thermochemical heat engine. In: Proceedings of the ASME International Solar Energy Conference (ISEC2006), Denver, Colorado, (2006)

Kodama, T., Gokon, N.: Thermochemical cycles for high-temperature solar hydrogen production. Chem. Rev. 107, 4048–4077 (2007)

Steinfeld, A.: Solar hydrogen production via a two-step water-splitting thermochemical cycle based on Zn/ZnO redox reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 27, 611–619 (2002)

Schunk, L.O., Haeberling, P., Wepf, S., Wuillemin, D., Meier, A., Steinfeld, A.: A receiver-reactor for the solar thermal dissociation of zinc oxide. J. Sol. Energy. Eng. 130, 021009 (2008)

Roeb, M., Sattler, C.: Isothermal water splitting. Science. 341, 470–471 (2013)

Gokon, N., Mataga, T., Kondo, N., Kodama, T.: Thermochemical two-step water splitting by internally circulating fluidized bed of NiFe\(_2\)O\(_4\) particles: successive reaction of thermal-reduction and water-decomposition steps. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 36, 4757–4767 (2011)

Neises, M., Tescari, S., de Oliveira, L., Roeb, M., Sattler, C., Wong, B.: Solar-heated rotary kiln for thermochemical energy storage. Sol. Energy. 86, 3040–3048 (2012)

Diver, R.B., Miller, J.E., Allendorf, M.D., Siegel, N.P., Hogan, R.E.: Solar thermochemical water-splitting ferrite-cycle heat engines. J. Sol. Energy. Eng. 130, 041001 (2008)

Kaneko, H., Lee, C.I., Ishikawa, Y., Hosogoe, K., Tamaura, Y.: Solar H2 production with Tokyo Tech rotary-type solar reactor to be tested using solar concentration system at CSIRO in Australia. In: Proceedings of the ASME 3rd International Conference of Energy Sustainability (ES2009), San Francisco, California, (2009)

Roeb, M., Säck, J.-P., Rietbrock, P., Prahl, C., Schreiber, H., Neises, M., de Oliveira, L., Graf, D., Ebert, M., Reinalter, W., Meyer-Grünefeldt, M., Sattler, C., Lopez, A., Vidal, A., Elsberg, A., Stobbe, P., Jones, D., Steele, A., Lorentzou, S., Pagkoura, C., Zygogianni, A., Agrafiotis, C., Konstandopoulos, A.G.: Test operation of a 100 kW pilot plant for solar hydrogen production from water on a solar tower. Sol. Energy. 85, 634–644 (2011)

Furler, P., Scheffe, J., Gorbar, M., Moes, L., Vogt, U., Steinfeld, A.: Solar thermochemical CO\(_2\) splitting utilizing a reticulated porous ceria redox system. Energy. Fuels. 26, 7051–7059 (2012)

Houaijia, A., Sattler, C., Roeb, M., Lange, M., Breuer, S., Sack, J.P.: Analysis and improvement of a high-efficiency solar cavity reactor design for a two-step thermochemical cycle for solar hydrogen production from water. Sol. Energy. 97, 26–38 (2013)

Rosensweig, R.E.: Ferrohydrodynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1985)

Chueh, W.C., Falter, C., Abbot, M., Scipio, D., Furler, P., Haile, S., Steinfeld, A.: High-flux solar-driven thermochemical dissociation of CO\(_2\) and H\(_2\)O using nonstoichiometric ceria. Science. 330, 1797–1800 (2010)

Lapp, J., Davidson, J.H., Lipiński, W.: Efficiency of two-step solar thermochemical non-stoichiometric redox cycles with heat recovery. Energy. 37, 591–600 (2012)

Ermanoski, I., Siegel, N.P., Stechel, E.B.: A new reactor concept for efficient solar-thermochemical fuel production. J. Sol. Energy. Eng. 135, 031002 (2013)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AGICO Inc. and especially Dr. Martin Chadima for providing experimental data for the pyromagnetic coefficient calculations. The first author would also like to especially thank Dr. Martin Roeb at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) for calling his attention to thermochemical two-step splitting reactions for hydrogen production.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Magnetic separation using a permanent magnet and movable parts

Although the main aim of this paper was to assess the feasibility of continuous magnetic separation between the magnetic phase (MOFe\(_2\)O\(_3\)) and non-magnetic phase (MO) of ferrites for hydrogen and/or CO production, eliminating the use of moving parts (mechanical separation), it is, nevertheless, interesting to explore the possibility of magnetic separation in ferrite systems using a permanent magnet combined with the use of movable parts. Figure 11 shows a possible conceptual schematic of this kind of separation device.

Magnetic agglomeration

In the presence of an external magnetic field at temperatures below the Curie temperature \(\Theta \), each Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particle is magnetized, and when their dipoles are aligned agglomeration can occur. In these circumstance, a certain amount of energy is needed to separate a pair of particles of diameter D. This magnetic dipole–dipole pair energy \(E_\mathrm{dd}\) when particles are in contact reduces to the following form [20]:

Two mechanism are available to disrupt the agglomerates. The first is thermal agitation, with the effectiveness of the disruption governed by the ratio [20]:

For particles to escape agglomeration, this ratio must be greater than unity, which implies that the particle diameter must satisfy:

For the magnetite particles working at \(T \approx 800\) K, this requires \(D \le 78\) nm.

The second mechanism available to disrupt agglomeration is magnetic shaking, thanks to the vigorous impact between particles. In this case, the effectiveness of the disruption is governed by the ratio:

Working at \(T \approx 800\) K this requires \(H \ge 10^4\) A m\(^{-1}\), which is the magnetic field of a modest handheld permanent magnet.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Arias, F.J., Parks, G.T. Magnetic separation for a continuous solar-two-step thermochemical cycle for solar hydrogen/CO production using ferrites. Int J Energy Environ Eng 6, 319–327 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0177-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0177-x