Abstract

Introduction

Giant inguinoscrotal hernias are rare but still exist even in developed countries. Although accompanied by a higher perioperative mortality, an elective surgical approach should be undertaken. In critically ill patients, however, the surgical intervention requires specific demands.

Methods

We report a case of a 45-year-old man who was referred to the hospital after perforation of the hernia with concomitant peritonitis and sepsis.

Results

After initial stabilization of the patient, a subtotal colectomy and a partial small bowl resection was performed. In a second step after stabilization of organ functions, the hernia sac was resected, and the abdominal cavity was reconstructed. The patient was discharged and is doing well until today but still refuses any plastic surgery.

Conclusion

Resection of giant inguinoscrotal hernia is feasible even in patients being administered in an emergency setting. Especially in case of an intra-abdominal infection, intestinal resection is the therapy of choice to allow the reconstruction of the abdominal cavity. A two-step approach should be considered to allow a successful recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A well-known complication of groin hernias is the increase in size advocating an early surgical treatment. However, in rare cases, patients refuse operative procedures. As a consequence, giant inguinoscrotal hernias develop. Over the past, different surgical repairs have been suggested. In this report, we now present a patient who initially refused surgery with subsequent scrotal perforation and septic complication followed by emergency hernia repair.

Case Report

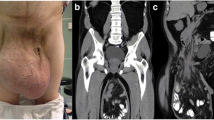

A 45-year-old man was taken to the emergency ward. Fourteen months before, he presented with a giant inguinoscrotal hernia but refused surgery. He was now recovered from his apartment due to his inability to walk by a gradually loss of strength and progressive increase of his hernia that now reached the calves. Within the last months, he used a small wagon to transport his hernia leading to an ulcer continuously discharging putrid liquid. Clinical and blood tests revealed a systemic inflammatory response syndrome with impairment of coagulation, anemia, severe hyponatremia, and a complete left-sided pleural effusion. Within the following hours, intubation and catecholamine therapy became necessary, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. Excluding acute ischemia, the CT scan (Fig. 1) revealed a complete dislocation of the small and the large bowel, descending of the duodenum and the pancreas, and intra- and extrahepatic cholestases and confirmed the congestion of the right kidney as initially seen on ultrasound. The ureter descended into the hernia sac and was dilated up to its return into the abdominal cavity.

Within the next 5 days, the patient was further stabilized, and surgery was attempted. Exploration of the abdominal cavity showed signs of peritonitis. Within the hernia sac, purulent liquid remained, and the penis was identified intra-abdominally. In a first step, the majority of the mobile large bowel (ascendens down to the sigmoideum) and distal parts of the ileum (200 cm behind the ligament of Treitz) were resected. After 48 h of stabilization, the majority of the hernia sac was resected. Identification of the testes was not possible. Due to the inability to close the fascia and due the inflammatory situation, the abdominal cavity was reconstructed using absorbable mesh grafts (Fig. 2).

During the following days, the patient recovered slowly. Mobilization was complicated by an a priori existing lesion of the nervus peroneus and a polyneuropathia. Five weeks after the initial surgery, the patient could be discharged from the hospital. In the following rehabilitation program, he regained the ability to walk and care for himself again. Until today, he refused any further plastic reconstruction.

Discussion

Giant inguinoscrotal hernias might be considered as negligible. However, they still occur, even in developed countries, and then present a challenging surgical problem. Defined as the extension below the midpoint of the inner thigh in the standing position,1 giant inguinoscrotal hernias still vary widely in their size and appearance. Depending on the comorbidities of the patients, different surgical approaches have been reported. They are all sharing the same strategy of relocating the organs into the abdominal cavity that have lost their “right of domain” without increasing the abdominal pressure excessively and thus reducing the venous return or a compromising of the pulmonary or cardiac function. In the past, two general principles have been advocated. On the one hand, the abdominal space is increased by (1) progressive pneumoperitoneum,2,3 (2) abdominal wall separation,4 or (3) combined mesh and flap techniques (including mesh repair to create an abdominal wall defect for increasing the intra-abdominal capacity).5,6 On the other hand, abdominal organs are resected to reduce the size of organs that need to be relocated.7 Endoscopic techniques have been reported but should be assessed very critically.8 The enlargement of the abdomen by pneumoperitoneum, in general, showed to be a valid method. However, in very large giant hernias, it failed several times.9,10 In situations of infected hernia sac, pneumoperitoneum should be avoided,11,12 and a stepwise procedure has previously been suggested.13 In these special situations, nonabsorbable meshes should be avoided due to their potential infection.14

Orchiectomy of non-necrotic testis is still controversy discussed as chances of testicular torsion or infection, or even recurrence is increased if left in place.15 With regard to the resection of the hernial sac, the development of scrotal hematoma and/or massive lymphedema is possible.9 Otherwise, redundant scrotal skin has the possibility to save as a safety net in case of recurrence of increased intra-abdominal pressure.10

Conclusion

Accompanied by an increased mortality rate, surgery should be advocated even for giant inguinoscrotal hernias. In septic patients, the inflammatory focus needs to be resected. An initial stabilization is advantageous if incarceration can be ruled out. To reconstruct the abdominal cavity, a two-step procedure should be pursued to allow a recovery from the initial resection and to regain organ function. To further reduce surgical trauma and operation time, subtle plastic reconstruction should be performed after complete recovery.

References

Hodgkinson DJ, McIlrath DC. Scrotal reconstruction for giant inguinal hernias. Surg Clin North Am 1984;64:307-313.

McAdory RS, Cobb WS, Carbonell AM. Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum for hernias with loss of domain. Am Surg 2009;75:504-508; discussion 508-509.

Caldironi MW, Romano M, Bozza F, Pluchinotta AM, Pelizzo MR, Toniato A, Ranzato R. Progressive pneumoperitoneum in the management of giant incisional hernias: a study of 41 patients. Br J Surg 1990;77:306-307.

Valliattu AJ, Kingsnorth AN. Single-stage repair of giant inguinoscrotal hernias using the abdominal wall component separation technique. Hernia 2008;12:329-330.

Berrevoet F, Martens T, Van Landuyt K, de Hemptinne B. The anterolateral thigh flap for complicated abdominal wall reconstruction after giant incisional hernia repair. Acta Chir Belg 2010;110:376-382.

El-Dessouki NI. Preperitoneal mesh hernioplasty in giant inguinoscrotal hernias: a new technique with dual benefit in repair and abdominal rooming. Hernia 2001;5:177-181.

Vasiliadis K, Knaebel HP, Djakovic N, Nyarangi-Dix J, Schmidt J, Buchler M. Challenging surgical management of a giant inguinoscrotal hernia: report of a case. Surg Today 2010;40:684-687.

Bernhardt GA, Gruber K, Gruber G. TAPP repair in a giant bilateral scrotal hernia—limits of a method. ANZ J Surg 2010;80:947-948.

Kyle SM, Lovie MJ, Dowle CS. Massive inguinal hernia. Br J Hosp Med 1990;43:383-384.

Merrett ND, Waterworth MW, Green MF. Repair of giant inguinoscrotal inguinal hernia using marlex mesh and scrotal skin flaps. Aust N Z J Surg 1994;64:380-383.

Veihelmann A, Ungeheuer A, Feussner H. [Case report: emergency surgery of a giant scrotal hernia]. Zentralbl Chir 2001;126:1018-1020.

Kovachev LS, Paul AP, Chowdhary P, Choudhary P, Filipov ET. Regarding extremely large inguinal hernias with a contribution of two cases. Hernia 2010;14:193-197.

El Saadi AS, Al Wadan AH, Hamerna S. Approach to a giant inguinoscrotal hernia. Hernia 2005;9:277-279.

Weiss CL, Brauckhoff M, Steuber J. [Emergency management of a monstrous inguinal hernia]. Zentralbl Chir 1997;122:931-933.

Serpell JW, Polglase AL, Anstee EJ. Giant inguinal hernia. Aust N Z J Surg 1988;58:831-834.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaedcke, J., Schüler, P., Brinker, J. et al. Emergency Repair of Giant Inguinoscrotal Hernia in a Septic Patient. J Gastrointest Surg 17, 837–839 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-2136-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-2136-7