Abstract

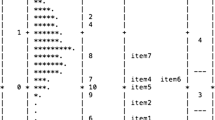

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in unethical work behavior. Several types of survey instruments to collect information about unethical work behavior are available. Nevertheless, to date little attention has been paid to design issues of those surveys. There are, however, several important problems that may influence reliability and validity of questionnaire data on the topic, such as social desirability bias. This paper addresses two important issues in the design of online surveys on unethical work behavior: the response scale for questions regarding the frequency of certain types of unethical work behavior and the location of the background questions in an online survey. We present the results of an analysis of a double split-ballot experiment in a large sample (n = 3,386) on governmental integrity. We found that, when comparing response scales that have labels for all categories with response scales that only have anchors at the end, the latter provided answers with higher validity. The study did not provide support for the conventional practice of asking background questions at the end.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unethical work behavior is a topic receiving much attention in fields such as business ethics, administrative ethics (subfield of public administration), criminology, organizational psychology etc. The various angles from which unethical work behavior is studied give rise to a wide variation of concepts. In criminology, concepts such as employee deviance and organizational misbehavior are used, whereas in business and administrative ethics research is often focused on integrity violations or unethical behavior. When studying the operationalisations of these concepts, however, it becomes clear that they often mean the same. In this study the term “unethical work behavior” is chosen.

The authors note that the measurement of “unethical work behavior” in OMB set 2 and set 3 was not ideal. The items were formulated in a broad way (e.g., “violating laws, rules or procedures to help a friend”). The reason for this way of formulating the items was two-fold. A first reason was based on theoretical arguments. The objective was to evaluate the correlation between specific types of ethical climate and the associated types of unethical work behavior. A second reason was that formulating more specific items would lead to an increased length of the survey.

To test possible differences, we used a χ 2 test for gender and Mann–Whitney U tests for age, level and length of service.

References

Ahern, N. R. (2005). Using the internet to conduct research. Nurse Researcher, 13, 55–70.

Arnold, H. J., & Feldman, D. C. (1981). Social desirability response bias in self-report choice situations. Academy of Management Journal, 24, 377–385.

Babbie, E. R. (1997). The practice of social research. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Bennett, R., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 349–360.

Beretvas, S. N., Meyers, J. L., & Leite, W. L. (2002). A reliability generalization study of the Marlowe–Crowne social desirability scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62, 570–589.

Billiet, J., & Waege, H. (2006). Een samenleving onderzocht. Methoden van sociaal-wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Antwerpen: De Boeck.

Borgers, N., Hox, J., & Sikkel, D. (2003). Research quality in survey research with children and adolescents: The effect of labeled response options and vague quantifiers. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 15, 83–94.

Borkeneau, P., & Ostendorf, F. (1992). Social desirability scales as moderator and suppressor variables. European Journal of Personality, 6, 199–214.

Bradburn, N. M., & Miles, C. (1979). Vague quantifiers. Public Opninion Quarterly, 43, 92–101.

Chung, J., & Monroe, G. S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44, 291–302.

Cohen, J. F., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (1998). The effect of gender and academic discipline diversity on the ethical evaluations, ethical intentions and ethical orientation of potential public accounting recruits. Accounting Horizons, 13, 250–270.

Cohen, J. F., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (2001). An examination of differences in ethical decision-making between Canadian business students and accounting professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 3, 319–336.

Crane, A. (1999). Are you ethical? Please tick yes□ or no□ on researching ethics in business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 20, 237–248.

Delbeke, K., Geeraerts, A., Maesschalck, J., & Hondeghem, A. (2008). Naar een meetinstrument ter ondersteuning van het ambtelijk integriteitsbeleid. Handleiding survey ‘Integriteit op het werk’. Leuven: Bestuurlijke Organisatie Vlaanderen.

Dillman, D. A. (2007). Mail and internet surveys. The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Dixon, P. N., Bobo, M., & Stevick, R. A. (1984). Response differences and preferences for all-category-defined and end-defined likert formats. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44, 61–66.

Edwards, A. L. (1957). The social desirability variable in personality assessment and research. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Finn, R. H. (1972). Effects of some variations in rating scale characteristics on the means and reliabilities of rating. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 32, 255–265.

Fowler, F. J. (1995). Improving survey questions. Design and implementation. London: Sage Publications.

Frankel, M. S., & Siang, S. (1999). Ethical and legal aspects of human subjects research on the internet. Washington, DC: AAAS Program on Scientific Freedom, Responsibility and Law.

Frederickson, H. G., & Walling, J. D. (2001). Research and knowledge in administrative ethics. In T. L. Cooper (Ed.), Handbook of administrative ethics (2nd ed., pp. 37–58). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University.

Frick, A., Bächtiger, M. T., & Reips, U.-D. (2001). Financial incentives, personal information and drop-out rate in online studies. In U.-D. Reips & M. Bosnjak (Eds.), Dimensions of internet science (pp. 209–219). Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Frisbie, D. A., & Brandenburg, D. C. (1979). Equivalence of questionnaire items with varying response formats. Journal of Educational Measurement, 16, 43–48.

Ganster, D. C., Hennessey, H. W., & Luthans, F. (1983). Social desirability response effects: Three alternative models. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 321–331.

Gaskell, G. D., O’Muircheartaigh, C. A., & Wright, D. B. (1994). Survey questions about the frequency of vaguely defined events. The effects of response alternatives. Public Opninion Quarterly, 58, 241–254.

Giles, W. F., & Feild, H. S. (1978). Effects of amount, format, and location of demographic information on questionnaire return rate and response bias of sensitive and nonsensitive items. Personnel Psychology, 31, 549–559.

Groves, R. M., & Cooper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in household interview survey. New York: Wiley.

Heerwegh, D. (2005). Effects of personal salutations in e-mail invitations to participate in a web survey. Public Opninion Quarterly, 69, 588–598.

Hindelang, M. J., Hirschi, T., & Weis, G. (1981). Measuring delinquency. Thoasand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Holtgraves, T. (2004). Social desirability and self-reports: Testing models of socially desirable responding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 161–172.

Huberts, L. W. J. C., Pijl, D., & Steen, A. (1999). Integriteit en corruptie. In C. Fijnaut, E. Muller, & U. Rosenthal (Eds.), Politie. Studies over haar werking en organisatie (pp. 433–472). Alphen aan den Rijn: Samsom.

Junger-Tas, J., & Marshall, I. H. (1999). The self-report methodology in crime research. Crime and Justice, 25, 291–367.

Kaptein, M., & Avelino, S. (2007). Measuring corporate integrity: A survey-based approach. Corporate Governance, 5, 45–54.

Kolthoff, E. (2007a). Ethics and new public management: Empirical research into the effects of businesslike government on ethics and integrity. Den Haag: Boom Juridische uitgevers.

Kolthoff, E. (2007a). Bing Integriteitmeter (unpublished survey). Den Haag: Dutch Office of Local Government Ethics.

Krosnick, J. A., & Fabrigar, L. R. (1997). Designing rating scales for effective measurement in surveys. In L. Lyberg, P. Biemer, M. Collins, E. de Leeuw, C. Dippo, N. Schwarz, & D. Trewin (Eds.), Survey measurement and process quality (pp. 141–165). New York: Wiley.

Lasthuizen, K. (2008). Leading to integrity. Empirical research into the effects of leadership on ethics and integrity. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Lasthuizen, K., Huberts, L. W. J. C., & Heres, L. (2011). How to measure integrity violations. Towards a validated typology of unethical behavior. Public Management Review, 13, 383–408.

Lee, R. M. (1999). Doing research on sensitive topics. London: Sage.

Loyens, K. (2012). Integrity secured. Understanding ethical decision making among street-level bureaucrats in the Belgian Labor Inspection and Federal Police. Leuven: KU Leuven.

Maesschalck, J. (2004). Towards a public administration theory on public servant’s ethics. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Mars, G. (1999). Cheats at work: An antrophology of workplace crime. Aldershot: Ashgate.

McDonald, G. (2000). Cross-cultural methodological issues in ethical research. Journal of Business Ethics, 27, 89–104.

Moxey, L. M., & Sanford, A. J. (1993). Communicating quantities: A psychological perspective. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15, 263–280.

Newstead, S. E. (1988). Quantifiers as fuzzy concepts. In T. Zétényi (Ed.), Fuzzy sets in psychology (pp. 51–72). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers.

Osgood, D. W., McMorris, B., & Potenza, M. T. (2002). Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance I: Item response theory scaling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 267–296.

Peeters, C. F. W. (2006). Measuring politically sensitive behavior. Using probability theory in the form of randomized response to estimate prevalence and incidence of misbehavior in the public sphere: a test on integrity violations. Amsterdam: Dynamics of Governance, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Pepper, S. (1981). Problems in the quantification of frequency expressions. In D. Fiske (Ed.), New directions for methodology of social and behavioral science: Problems with language imprecision (pp. 25–41). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Peterson, D. K. (2002). The relationship between unethical behavior and the dimensions of the Ethical Climate Questionnaire. Journal of Business Ethics, 41(4), 313–326.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 805–817.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1992). Social desirability bias in ethics research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2, 183–205.

Randall, D. M., & Gibson, A. M. (1990). Methodology in business ethics research: A review and critical assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 457–471.

Roberson, M. T., & Sundstrom, E. (1990). Questionnaire design, return rates, and response favorableness in an employee attitude questionnaire. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 354–357.

Sampford, C., Shacklock, A., Connors, C., & Galtung, F. (2006). Measuring corruption. Hampshire: Ashgate.

Schoderbek, P. P., & Deshpande, S. P. (1996). Impression management, overclaiming, and perceived unethical conduct: The role of male and female managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 409–414.

Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports. How the questions shape the answers. American Psychologist, 54, 93–105.

Skipper, R., & Hyman, M. R. (1993). On measuring ethical judgements. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(7), 535–545.

Sloan, J. J., Bodapati, M. R., & Tucker, T. A. (2004). Respondents misreporting of drug use in self-reports: Social desirability and other correlates. Journal of Drug Issues, 34, 269–292.

Stoop, I. A. L. (2005). The hunt for the last respondent. The Hague: Social and Cultural Planning Office of the Netherlands.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N. M. (1982). Asking questions. A practical guide to questionnaire design. London: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Tourangeau, R., & Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format and question context. Public Opninion Quarterly, 60, 275–304.

van der Heijden, P. G. M., Van Gils, G., Bouts, J., & Hox, J. J. (2000). A comparison of randomized response, computer-assisted self-interview, and face-to-face direct questioning. Sociological Methods and Research, 28, 505–537.

Vardi, Y., & Wiener, Y. (1996). Misbehavior in organizations: A motivational framework. Organization Science, 7, 151–165.

Victor, B., Trevino, L. K., & Shapiro, D. L. (1993). Peer reporting of unethical behavior: The influence of justice evaluations and social context factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(4), 253–263.

Wanek, J. E. (1999). Integrity and honesty testing: What do we know? How do we use it? International Journal of Selection & Assessment, 7, 183–195.

Weisberg, H. F. (2005). The total survey error approach: A guide to the new science of survey research. London: University of Chicago Press.

Wells, W. D., & Smith, G. (1960). Four semantic rating scales compared. Journal of Applied Psychology, 44, 393–397.

Wildman, R. C. (1977). Effects of anonymity and social setting on survey responses. Public Opninion Quarterly, 41, 74–79.

Wright, D. B., Gaskell, G. D., & O’Muircheartaigh, C. A. (1994). How much is ‘Quite a bit’? Mapping between numerical values and vague quantifiers. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8, 479–496.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by project grants from the “Steunpunt Bestuurlijke Organisatie Vlaanderen.” The authors wish to thank Karlien Delbeke, Annelies De Schrijver, Arne Geeraerts, Annie Hondeghem, Kim Loyens and Stefaan Pleysier for their helpful comments and suggestions. The authors would also like to thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewer for constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

List of Items of Unethical Work Behavior of UWB Set 1 (Proxy-Report)

-

1.

Minimal effort by employees (laziness).

-

2.

Gossiping.

-

3.

Use of the internet, e-mail, or telephone above the permitted standard.

-

4.

Favoritism by superiors.

-

5.

Accepting small gifts from external parties.

-

6.

Falsely reporting in sick.

-

7.

Use of organizational resources for private purposes.

-

8.

Careless handling of employees or external parties.

-

9.

Neglecting core tasks or responsibilities in order to engage in more pleasant business.

-

10.

Bullying (e.g., teasing, ignoring, or isolating).

-

11.

Careless use of organizational properties.

-

12.

Executives placing unaccepted pressure to influence things.

-

13.

Careless handling of confidential information.

-

14.

Disclosing confidential information to external parties.

-

15.

Politicians placing unacceptable pressure to influence things.

-

16.

Excessive use of alcohol while on duty.

-

17.

Concealing information from the supervisory authorities.

-

18.

Theft of organizational properties.

-

19.

Favoring of friends or family outside the organization.

-

20.

Setting a bad example in private time.

-

21.

Deliberately delaying decision-making processes.

-

22.

Incorrect handling of expense claims.

-

23.

Not reporting illegal behavior.

-

24.

Giving advice to externals in private time concerning the organizational specialism.

-

25.

Discrimination based on sex, race or sexual orientation of colleagues.

-

26.

Sideline activities or jobs that might pose a conflict of interest.

-

27.

Unauthorized use of a colleague’s password or access code.

-

28.

Deliberately giving false information in reports and/or evidence.

-

29.

Accepting bribes (money or favors) to do or neglect something while at work.

-

30.

Accepting gifts of more serious value from external parties.

-

31.

Sexual intimidation.

-

32.

Procuring confidential information to third parties for remuneration.

List of Items of Unethical Work Behavior of UWB Set 2 (Proxy-Report) and UWB Set 3 (Self-Report)

-

1.

Violating laws, rules or procedures because you do not agree with them by your own personal beliefs.

-

2.

Ignoring important goals to work efficiently.

-

3.

Violating laws, rules or procedures to protect your own interest.

-

4.

Violating laws, rules or procedures to help a friend.

-

5.

Violating laws, rules or procedures to protect colleagues from the same team or group.

-

6.

Violating laws, rules or procedures to help a citizen in the course of your occupation.

-

7.

Hiding unethical issues from people outside the organization to protect the image of the organization.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wouters, K., Maesschalck, J., Peeters, C.F.W. et al. Methodological Issues in the Design of Online Surveys for Measuring Unethical Work Behavior: Recommendations on the Basis of a Split-Ballot Experiment. J Bus Ethics 120, 275–289 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1659-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1659-5