Abstract

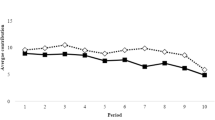

In many cases individuals benefit differently from the provision of a public good. We study in a laboratory experiment how heterogeneity in returns and uncertainty about the own return affects unconditional and conditional contribution behavior in a linear public goods game. The elicitation of conditional contributions in combination with a within subject design allows us to investigate belief-independent and type-specific reactions to heterogeneity. We find that, on average, heterogeneity in returns decreases unconditional contributions but affects contributions only weakly. Uncertainty in addition to heterogeneity reduces conditional contributions slightly. Individual reactions to heterogeneity differ systematically. Selfish subjects and one third of conditional cooperators do not react to heterogeneity whereas the reactions of the remaining conditional cooperators vary. A substantial part of heterogeneity in reactions can be explained by inequity aversion with respect to different reference groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that we only consider heterogeneity in valuations of public goods. For heterogeneity in productivity see e.g. Tan (2008) or Fellner et al. (2011) and for heterogeneity in valuations of the private good see e.g. Falkinger et al. (2000). For a meta study on determinants of contributions in linear public goods games see Zelmer (2003). Her findings indicate that heterogeneity decreases contributions; strongly for endowment heterogeneity and weakly for heterogeneity in MPCRs.

We do not report results on a seventh decision (a donation decision) made by our subjects which was also elicited and included in the random selection of payoffs.

Averages are rounded to integer numbers, i.e. subjects have to fill in 21 values. The translated instructions in the online appendix provide a screenshot.

A copy of translated instructions can be found in the online appendix.

Note that in our experiment, subjects do not have explicit information about inequity in contributions of the other group members but only condition on the average contribution of their group members. Thus our study focuses on public goods for which people are aware that they may benefit equally or unequally but individual contributions are not observable (e.g. the water quality of a lake or air quality in a city). Results by Cheung (2011) and Wolff (2013) show that if information on individual contributions is known, higher variances in contributions will cause a reduction in conditional contributions.

Note that all members making the same contribution is not plausible in an equilibrium with positive contributions. With equal contributions, it is optimal for individuals with the high MPCR to contribute the same amount as the group average but for individuals with the low MPCR it is optimal to contribute 1/3 of the group average.

Besides, because the threshold for a contribution equalizing payoffs is lower for the player with the high MPCR and higher for those with the low MPCR than the threshold for the situation in which all individuals face the same MPCR of 0.4, we should also observe more people contributing positive amounts in situation CC05 than in CC04, and more in CC04 than in CC03.

Note that the threshold is smaller for a player with the low MPCR than for an individual with the high MPCR because it is less costly for the player with the low MPCR to reduce inequality (he loses 0.7 by contributing a unit and each member of his reference group gains 0.5 whereas a player with the high MPCR loses 0.5 when contributing 1 unit while his reference group members gain only 0.3 each).

Due to the discrete nature of the experiment only a finite set of contribution schedules exists. The logic of the numerical analysis works as follows. First, it can be shown that conditional contributions are monotonically increasing in for both the homogeneous and the heterogeneous case (with and without uncertainty about the own MPCR). Because this is the case, it is sufficient to show in a second step that the increase in \(\vartheta _\mathrm{i} \) increases conditional contributions “step wise” by one unit across the treatment in the order shown such that the weak inequalities CC05 = CC04 = CCun0305 = CC03 always holds.

We do not include the optimal contributions for CCu0305, which are weakly below optimal contribution in CC04, in order not to charge the figure unnecessarily here.

This results holds irrespective of the order in which subjects played the game.

The exceptions are group averages of 12 and 17.

As a comparison, Fischbacher et al. (2001) find about one third of subjects classified as free riders whereas about 50 % are conditionally cooperative.

Six out of 52 as selfish classified subjects contribute more than zero in UC03, UC05. Among them four who slightly increase contributions in both UC03 and UC05 and two who only increase their contributions in UC05.

The significance can be confirmed with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

On theoretical grounds no reaction to heterogeneity in returns may also result from comparisons in contributions instead of final payoffs. However, in the experiment subjects do not observe individual contributions and may thus only match average contributions. It is also plausible that subjects facing first homogeneity and then heterogeneity stick to their behavior in the homogeneous treatment because they are missing information necessary to fulfill their fairness norms in the heterogeneous case (e.g. individual contributions). However, the data do not suggest such an order effect. The probability to be in the group that does not react to heterogeneity is not significantly different (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, \(p\) = 0.413) and even lower when facing homogeneity first (0.184) compared to facing heterogeneity first (0.228).

We cannot separate subjects comparing themselves to subjects with the opposite MPCR from subjects comparing to all others, because the theoretical predictions do not differ qualitatively.

Heterogeneity averse people are actually classified into two different clusters. Although average Diff03 and average Diff05 have the same sign in both clusters, the magnitude is different. We group these two clusters because for both Diff03 and Diff05 are strongly negative. Each cluster presents 8.3 % of the population. In the first cluster, average Diff03 is \(-\)6.94 and average Diff05 is \(-\)6.86 while in the second cluster these values are respectively \(-\)2.97 and \(-\)2.54.

References

Anderson LR (2001) Public choice as an experimental science. In: Shughart W, Razzolinis L (eds) The Elgar companion to public choice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 497–511

Bagnoli M, McKee M (1991) Voluntary contribution games: efficient private provision of public goods. Econ Inq 29(2):351–366

Bohm P (1972) Estimating demand for public goods: an experiment. Eur Econ Rev 3(2):111–130

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2000) ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev 90(1):166–193

Carpenter J, Bowles S, Gintis H, Hwang SH (2009) Strong reciprocity and team production: theory and evidence. J Econ Behav Org 71(2):221–232

Chan K, Mestelman S, Moir R, Muller R (1999) Heterogeneity and the voluntary provision of public goods. Exp Econ 2(1):5–30

Chaudhuri A (2011) Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp Econ 14(1):47–83

Cheung S (2011) New insights into conditional cooperation and punishment from a strategy method experiment. IZA discussion paper no. 5689.

Clark AE, Oswald AJ (1996) Satisfaction and comparison income. J Public Econ 61(3):359–381

Dickinson D (1998) The voluntary contributions mechanism with uncertain group payoffs. J Econ Behav Org 35(4):517–533

Dufwenberg M, Kirchsteiger G (2004) A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games Econ Behav 47(2):268–298

Engel C, Kube S, Kurschilgen M (2011) Can we manage first impressions in cooperation problems? An experimental study on “Broken (and Fixed) Windows”. Working paper series of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods

Falk A, Fischbacher U (2006) A theory of reciprocity. Games Econ Behav 54(2):293–315

Falkinger J, Fehr E, Gächter S, Winter-Ebmer R (2000) A simple mechanism for the efficient provision of public goods: experimental evidence. Am Econ Rev 90(1):247–264

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q J Econ 114(3):817–868

Fellner G, Iida Y, Kröger S, Seki E (2011) Heterogeneous productivities in public good production—An experimental study. IZA Bonn, Working Paper No. 5556

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E (2001) Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ Lett 71(3):397–404

Fisher J, Isaac R, Schatzberg J, Walker J (1995) Heterogenous demand for public goods: behavior in the voluntary contributions mechanism. Public Choice 85(3):249–266

Gächter S (2007) Conditional cooperation: behavioral regularities from the lab and the field and their policy implications. In: Frey B, Stutzers A (eds) Economics and psychology: a promising new cross-disciplinary field. MIT Press, Cambridge

Gangadharan L, Nemes V (2009) Experimental analysis of risk and uncertainty in provisioning private and public goods. Econ Inq 47(1):146–164

Greiner B (2004) An online recruitment system for economic experiments. Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen GWDG Bericht 63, K. Kremer and V. Machos, Göttingen, pp 79–93

Isaac R, Walker J (1988) Group size effects in public goods provision: the voluntary contributions mechanism. Q J Econ 103(1):179–199

Konow J (2003) Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories. J Econ Lit 41(4):1188–1239

Konow J, Saijo T, Akai K (2009) Morals and mores? Experimental evidence on equity and equality. Working paper, Loyola Marymount University

Ledyard JO (1995) Public goods: a survey of experimental research. In: Roth AE, Kagels JH (eds) The handbook of experimental economics. Princeton University Press, Princetown, pp 111–181

Levati M, Morone A, Fiore A (2009) Voluntary contributions with imperfect information: an experimental study. Public Choice 138(1):199–216

Marwell G, Ames R (1980) Experiments on the provision of public goods. II. Provision points, stakes, experience, and the free-rider problem. Am J Sociol 85(4):926–937

Nikiforakis N, Noussair CN, Wilkening T (2012) Normative conflict and feuds: the limits of self-enforcement. J Public Econ 96(9–10):797–807

Rabin M (1993) Incorporating fairness into game—theory and economics. Am Econ Rev 83(5):1281–1302

Reuben E, Riedl A (2009) Public goods provision and sanctioning in privileged groups. J Confl Resolut 53(1):72

Reuben E, Riedl A (2013) Enforcement of contribution norms in public good games with heterogeneous populations. Games Econ Behav 77(1):122–137

Selten R (1967) Die Strategiemethode zur Erforschung des eingeschränkt rationalen Verhaltens im Rahmen eines Oligopolexperimentes. In: Sauermanns H (ed) Beiträge zur experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung, Tübingen, pp 136–168

Tan F (2008) Punishment in a linear public good game with productivity heterogeneity. De Econ 156(3):269–293

Ward JH (1963) Hierachical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc 58:236–244

Wolff I (2013) Cooperation when player types are common knowledge. Working Paper

Zelmer J (2003) Linear public goods experiments: a meta-analysis. Exp Econ 6(3):299–310

Acknowledgments

We thank Kate Bendrick, Lisa Bruttel, Gerald Eisenkopf, Pascal Sulser, Verena Utikal and Irenaeus Wolff as well as the participants of the ESA Meeting 2010 in Copenhagen, the THEEM workshop 2010 in Kreuzlingen and the ASFEE Conference 2011 in Fort-de-France as well as two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. Financial support is acknowledged from the Swiss Federal Office of Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fischbacher, U., Schudy, S. & Teyssier, S. Heterogeneous reactions to heterogeneity in returns from public goods. Soc Choice Welf 43, 195–217 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-013-0763-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-013-0763-x