Abstract

Purpose

The use of stem cells in regenerative medicine offers hope to treat numerous orthopaedic disorders, including articular cartilage defects. Although much research has been carried out on chondrogenesis, this complicated process is still not well understood and much more research is needed. The present review provides an overview of the stages of chondrogenesis and describes the effects of various growth factors, which act during the multiple steps involved in stem cell-directed differentiation towards chondrocytes.

Methods

The current literature on stem cell-directed chondrogenesis, in particular the role of members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily—TGF-βs, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs)—is reviewed and discussed.

Results

Numerous studies have reported the chondrogenic potential of both adult- and embryonic-like stem cells and the role of growth factors in programming differentiation of these cells towards chondrocytes. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult multipotent stem cells, whereas induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) are reprogrammed pluripotent cells. Although better understanding of the processes involved in the development of cartilage tissues is necessary, both cell types may be of value in the clinical treatment of cartilage injuries or osteoarthritic cartilage lesions.

Conclusions

MSCs and iPSCs both present unique characteristics. However, at present, it is still unclear which cell type is most suitable in the treatment of cartilage injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently available surgical tissue repair techniques have been classified as palliative (debridement, lavage), reparative (marrow stimulation techniques), or restorative (osteochondral grafting, autologous chondrocyte implantation) [1]. The main goals of surgical interventions are pain relief and improvement of joint function. The optimal strategy will depend on the size and location of the lesion, and the patient’s physical condition and pre-operative status [2]. Each of these factors should be carefully considered, since all surgical methods have some limitations. Joint lavage and debridement—procedures that wash out and remove debris, loosen cartilage fragments, and act as inflammatory mediators—are considered the first line treatment in smaller lesions and in low-demand patients. Marrow stimulating techniques, such as microfractures, are used to restore the cartilage surface by creating a blood clot originating from subchondral bone blood vessels. This technique is recommended in the case of defects ranging in size from 2 to 4 cm², and brings improvement in up to 67% of patients; however, this procedure is not suitable for larger lesions, where it has a high failure rate [3]. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is presently the most advanced technique for larger lesions (2–10 cm²). ACI is a two-step procedure. The first step involves tissue fragment debridement and lavage of the lesion site accompanied by cartilage biopsy. In the second step, the isolated chondrocytes are cultured and implanted into the cartilage defect site [4]. In the first generation ACI, a periosteal flap is used as a cover for implanted cells; however, the periosteum often leads to hypertrophic changes in the cartilage [5]. To avoid this undesired side effect, a recently proposed technique (second generation ACI) employs commercially available biomaterial membranes (scaffolds) as a cover for the implanted cells [6]. Application of an appropriate scaffold has been found to enhance cell proliferation and maturation [7]. The chondrocyte proliferation rate is a function of the initial number of cultured cells and the choice of appropriate articular cartilage layer as a cell source. The best results are obtained when chondrocytes are taken from the deeper zones and cultured at low cell densities [8].

Despite improvements in the ACI technique, disadvantages remain, most of which are related to the limited number of chondrocytes available for the cell culture, and re-differentiation of cells during tissue formation. To overcome the limitations connected with allogenic and autologous tissue grafts, research has turned to stem cell-directed therapies, a relatively novel concept in regenerative medicine. This approach, based on the use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), will probably be routinely employed in future because the use of such techniques would eliminate the need to use autologous tissue for grafting [9]. However, relatively high concentrations of BMPs are required to overcome the effect of BMP-antagonists, such as noggin [10].

An interesting approach includes promotion of the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-directed chondrogenesis by co-culture of MSC with chondrocytes. The chondrogenic cells secrete many factors that stimulate MSC differentiation [11]. While several animal and clinical studies along these lines have been conducted, better understanding of the molecular events underlying the development of cartilaginous tissue is necessary [12].

Chondrogenesis

Chondrogenesis at a cellular level

Chondrogenesis proceeds in two main stages: condensation and differentiation. During the condensation stage, the precartilaginous mesenchyme is divided into chondrogenic and non-chondrogenic domains. The condensation starts with cell movement followed by an increase in cell-packing density. This process is associated with enhanced cell-to-cell contacts and mutual interactions due to the adhesion molecules, Ca2 - dependent N-cadherin and Ca2+- independent N-CAM, as well as the gap junctions [13].

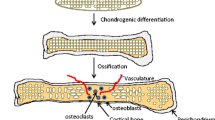

The differentiation stage comprises cell-matrix interactions, facilitated by the binding of fibronectin to syndecan. The increased cell proliferation and ECM remodeling is associated with the appearance of tenascin, matrilins and thrombospondins, such as, for example, cartilage oligomeric protein (COMP), as well as with the disappearance of type I collagen, fibronectin and N-cadherin. These events result in the transformation of chondroprogenitor cells into fully differentiated chondrocytes [14], while the prechondrogenic clusters develop into the ECM components, including type II collagen and aggrecan [15]. When chondrocytes enlarge, they enter the hypertrophic phase. In this phase the ECM is enriched in type X collagen and fibronectin. Then the chondrogenic cells change their environment through mineralization by calcium salts. During endochondral ossification, the chondrocytes undergo apoptosis followed by blood vessel invasion. Next, bone osteoprogenitors and the cartilagenous matrix are replaced by the mineralized matrix [16]. Another significant event is the change in fibronectin expression, as three different isoforms of this glycoprotein emerge [17]. The most suitable markers of the stages in this process are the various collagen types, with expression of type I, III and V collagens specifically marking condensation of the mesenchymal cells. Chondroprogenitor cell differentiation reveals the expression of cartilage-specific collagens (types II, IX and XI). Ultimately, the proliferating chondrocytes express type VI collagen as well as matrilin 1, while type X collagen indicates the hypertrophic zone [18].

Chondrogenesis is also connected with morphological changes of the cells. The chondroprogenitors, which are elongated and fibroblast-like, transform into spherical chondroblast- and chondrocyte-like cells [19]. The changes occurring at the cellular level result from the events taking place at a molecular level.

Chondrogenesis at a molecular level

The principle regulators of chondrogenesis are the members of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and members of the wingless-type (Wnt) signaling pathway [20]. The TGF-β superfamily members regulate cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis during embryogenesis. They include the secretory isoforms: TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3, with TGF-β3 having the highest chondrogenic potential of all isoforms, and their action results in rapid cell differentiation [21]. The TGF-βs and BMPs bind to the extracellular domains of specific receptors containing serine/threonine kinase activity in their intracellular domains, and require Sma and Mad related (SMAD) proteins for signal transduction within the cells (Fig. 1). Upon binding of the ligand to the receptor, homodimeric complexes of the receptor are formed, resulting in one subunit phosphorylating its partner subunit on serine/threonine residues. This starts a cascade of events involving phosphorylation of SMAD proteins. The TGF-β pathway requires SMAD 2 and SMAD 3, whereas the BMP signaling is dependent upon SMAD 1, 5 and 8. The phosphorylated receptor-regulated Smads (R-SMAD) reacts with SMAD4 to create a heterocomplex. The complex, consisting of R-SMAD and common-mediator Smad (Co-SMAD), enters the nucleus and by binding to promoters of target genes, controls their transcription (Table 1) [22].

The transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway. TGF-β binds to the receptor TGF-β-RII. After binding to TGF-β, TGF-β-RII recruits and phosphorylates TGF-β-RI, leading to activation of Smad2 and Smad3 by phosphorylation. This process is inhibited by Smad6/7. Activated Smad2 and Smad3 form heterodimers with Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus. Together with co-activators, co-repressors, and other transcription factors, the Smad complex regulates gene expression

Another way to regulate many cellular processes employs the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway using the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs), the C-Jun-NH2-terminal kinases (JNKs) as well as the p38 MAPK (Fig. 2) [23]. Protein kinase A (PKA) potentiates these effects, acting via phosphorylation of Ser/Thr residues of crucial substrates, as well as by indirectly regulating the expression of cyclic Adenosine 3, 5′-monophospahte (cAMP) responsive genes via the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), which binds to the CRE sites in the promoters of target genes. PKA also regulates chondrogenesis through activation of protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) [19] in cytosol and membrane fractions of mesenchymal cells during chondrogenesis [24]. In addition, PKA phosphorylates transcription factor Sox9 (sex determining region Y box 9) resulting in its transfer to the nucleus and augmentation of the transcriptional activity of these genes [22, 23]. The expression of Sox9 is up-regulated by sonic hedgehog transcription factor (SHH), which induces Bapx1 expression, which, in turn, indirectly up-regulates Sox9 expression. In cooperation with BMPs, a positive feedback loop is formed between Bapx1 and Sox9, which influences the expression of chondrogenic factors [25].

Other members of the Sox family (L-Sox5 and Sox6) are also involved in chondrogenesis. Sox9 and Runt-related transcription factor2 (Runx2) are the principal regulators, but they differ in function; while Sox9 leads to articular cartilage formation, Runx2 is involved in hypertrophic maturation of the cells [18]. Both factors are expressed throughout the entire chondrogenic process, starting from mesenchymal condensation and ending with terminal chondrocyte hypertrophy. The main function of Sox9 is to guarantee cell survival by activating the expression of type II collagen, alpha I gene (Col2a1), and other early cartilage marker genes [26]. Sox9 acts through its carboxyl terminal domain, which interacts with the CREB-binding protein (CRBP)/p300 complex, inducing the expression of specific chondrogenic genes [27].

The role of growth factors in chondrogenesis

The influence of BMP subfamily signaling polypeptides results in various biological responses such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [28, 29]. BMP-2 is commonly found in cartilage and bone but generally not in tendons [30]. It increases binding of the NF-Y/p300 complex to Sox9 promoter, which results in Sox9 accumulation. In addition, BMP-2 is involved in histone hyperacetylation and methylation of the Sox9 promoter [31]. Recombinant human BMP-4 induces early chondrogenesis through the mediation of Runx2, while BMP-2 and BMP-7 stimulate cellular condensation. Moreover, BMP-4 stimulates the synthesis of type II collagen, aggrecan, and the ECM proteins. It is worth mentioning that BMPs, apart from promoting chondrogenesis, are able to stimulate endochondral ossification [32]. BMP-1, -2 and -3, differential splicing products of the Bmp-1 transcript, in combination with BMP-7 (known as osteogenic protein-1 [OP-1]), enhance bone formation via osteoblast production and control and remodel the ECM proteins whose distribution depends on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity. However, despite the increased use of BMPs to improve bone healing, it was recently reported that administration of human BMP-7 and autologous bone grafting is no better than autologous grafting alone in patients with congenital pseudoarthrosis of the tibia [33].

The increase of Bmp-1 expression results in an increased expression of type I collagen and osteocalcin [34]. BMP-6 is a very effective regulator of MSC differentiation into osteoblasts during both development and adulthood. The endogenous expression of BMP-6 is up-regulated by the EGF-like factor and might contribute to the creation of bone-forming cells from MSCs [35]. BMP-7 is a crucial factor in skeletal development. Under pathologic conditions, BMP-7 plays a protective role for normal and OA chondrocytes by improving their survival and anabolic properties and by its ability to repair damaged cartilage [36]. The cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins CDMP-1, -2, and -3 (also known as BMP-14, -13 and -12, respectively) are responsible for both evolution of cartilaginous tissue during early limb development and the formation of the articular joint cavity during development. Moreover, they also play a very important role in the regeneration and maintenance of the articular cartilage [37].

Mammalian fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are a family of proteins considered paracrine regulators engaged in tissue patterning and organogenesis during embryonic development. FGF-18 has an anabolic effect on cartilaginous tissue, while FGF-2 participates in cartilage homeostasis [38]. The Wnt signaling pathway influences chondrogenesis via regulation of FGF synthesis. The type of response depends on the Wnt-2a and Wnt-2c proteins, which induce FGF-10 and FGF-8 at early stages of development. The members of the FGF family are engaged in limb initiation and limb bud outgrowth. The most important FGF family member affecting chondrogenesis is FGF-2, which functions as an effective mitogen for cell types of mesenchymal origin. Although the action of FGF-2 in chondrogenesis is not completely understood, it has been suggested that this factor might enhance the differentiation of human MSCs into chondrocytes [39]. Activated forms of FGF-10 and FGF-8 act in positive feedback loops. FGF-10 affects the expression of Wnt-3a, thus influencing β-catenin synthesis, and maintains its own expression via FGF-8 [40]. Homeobox (Hox) transcription factors are essential for activating expression of FGF-8 as well as SHH genes. The role of these factors, encoded by the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters, is crucial for the condensation stage of chondrogenesis [14].

IGFs play an important role in skeletal development. They stimulate cell proliferation, and regulate apoptosis and expression of chondrogenic markers. The cellular response to IGFs requires type I tyrosine kinase receptor (IGFIR). IGF binding results in activation of four signaling pathways: MAP kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase-kinase 1/2 (MEK 1/2), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk 1/2) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-Akt (P13K-Akt) [41].

Osteoarthritis (OA) appears when an imbalance between the synthesis and degradation of ECM components occurs, primarily type II collagen, and aggrecan. MMPs are also involved in this process [42]. FGF-18 and FGF-9, in association with fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR-1), induce the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor, VEGFR-1, thus promoting vascular invasion of the tissue in the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones [40]. Type II collagen is the best-known and most useful marker of the chondrocyte phenotype. Its synthesis is programmed by two RNA isoforms—the long (IIA) and the short (IIB) isoforms—generated by alternative splicing. The long form is characteristic of pre-chondrocytes, and the short one of mature chondrocytes [43]. The end of the proliferative stage and the emergence of the post-proliferative stage is accompanied by the presence of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), expressed in the periarticular region by proliferating chondrocytes and perichondrial cells. The PTHrP receptor is not expressed in undifferentiated cells but it is up-regulated in MSCs that undergo chondrogenic differentiation [44]. The Indian hedgehog (IHH) protein likely stimulates PTHrP production in the periarticular growth plate, thus delaying the switch from the proliferative to the hypertrophy phase. Moreover, IHH supports chondrocyte proliferation via PTHrP-independent arrangements [45]. The HH pathways are involved in chondrogenesis, chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, as well as in OA development. IHH and SHH are ligands of the HH pathway. SHH signaling induces BMPs pathways and controls MSC differentiation towards the chondrogenic lineage in vivo [46]. Better control of the chondrogenic process in connection with the use of stem cells can contribute to more successful treatment of OA.

Evans [47] reviewed studies that used gene therapy to repair damaged bones and cartilage, both in animal models and in humans, using either non-viral or viral vectors. The author found that several major strategies were successful, as follows: (i) direct injection of DNA or vectors containing genes encoding growth factors into injury sites; (ii) the use of genetically modified allogeneic cell lines; and (iii) intra-operative tissue harvesting (either intact or isolated cells) followed by transduction with viral vectors and return to the injury site. Furthermore, Evans concludes that chondrocytes, either transduced or transfected by DNA cloned in an appropriate vector, stimulate chondrogenesis [47].

The use of stem cells in the treatment of cartilage defects

Mesenchymal stem cells

MSCs are multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into a number of different cell types. MSCs are non-hematopoietic cells that originate from several sources, although the best-characterized populations derive from bone marrow (BM-MSCs). Besides BM-MSCs for cartilage repair cells have been isolated from various tissues such as synovium, periosteum, adipose tissue or synovial fluid [12, 48, 49]. Among these cell lines, synovium-derived MSCs (SMSCs) have been recently recognized as an appropriate cell type with chondrogenic potential and high proliferative capacity [49]. In vitro studies showed that the chondrogenesis process of SMSCs could be successfully conducted using TGF-β1 and BMP-2 [50]. Moreover, SMSCs could be also easily harvested, for example, during an arthroscopic examination of the joint. Chondrocytes derived from the MSC are suitable for application in regenerative medicine, since they are also easy to isolate and manipulate [48]. During maintenance, proliferation, migration and subsequent differentiation, MSCs are involved in the reciprocal transfer of many signals with neighbouring cells [51–53]. Under appropriate culture conditions, MSCs can differentiate into fibroblasts or adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages [54]. The classification of MSCs is troublesome, due to both a lack of a clear definition and generally accepted selective markers. Nevertheless, the basic identification standards include the following: adherence properties, expression of cell surface antigens (such as CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD 106 and CD 166), and the absence of hematopoietic markers [46, 55]. Although chondrogenesis in vitro seems to be relatively simple, it was shown that during directed differentiation of MSCs up to 300 genes are misregulated [56].

Stem cell homing involves an active recruitment of endogenous cells that can be found in the tissue niche. Endogenous stem cell migration can occur in two ways. The first is through the circulatory system, aided by interactions with microvascular endothelial cells at a target site. This process includes stem cell rolling, adhesion, chemotaxis, and invasion. The second way, which is independent of blood flow, involves cell trafficking and requires amoeboid cell movement [57]. Unfortunately, MSCs do not migrate easily in the bloodstream. For this reason, translocation of MSCs from bone marrow to peripheral blood is a challenge [58]. MSCs are suitable for allogeneic transplant due to their immunoprivileged properties. In MSCs, the expression of major histocompatibility complex I proteins (MHC I) is low and there is no expression of MHC II, which decreases the risk of transplant rejection [59]. Apart from revealing multipotency, MHCs can modulate immune response and inflammation. In addition, they release trophic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory factors that exhibit pro-regenerative properties [60]. Moreover, in contrast to mature chondrocytes, MSCs can be expanded ex vivo to sufficiently high numbers, making them an abundant cell source for autologous cell therapies. Unfortunately, it is difficult to obtain a pure population of stem cells, as well as precisely control the direction of MSC differentiation [61]. Another disadvantage is the relatively low percentage of MSCs in bone marrow; moreover, in the elderly, the cell proliferation rate of isolated MSCs is often insufficient. Finally, in OA patients, isolated MSCs have a lower differentiation rate, which is another obstacle that needs to be overcome before the technique can become more widely used [62].

Induced pluripotent stem cells

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) possess the capacity to develop into derivatives of all three primary germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm). They have unlimited self-renewal capacity, high developmental plasticity, and reduced immunogenic properties. These characteristics explain the enormous interest in these cells, which can be used as patient-specific cells to repair musculoskeletal tissues that have limited regeneration potential, such as bone or cartilage [63]. Most human iPSCs described in the literature originate from fibroblasts. They are created by reprogramming involving forced expression of transcription factors Sox2, Oct3/4, Klf4, and Myc in somatic cells [64]. The coordinated expression of pluripotency genes and/or an oncogene causes the re-establishment of the transcriptional information and cell morphology [65]. However, these similarities do not indicate that iPSCs are equivalent to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) at a molecular or functional level. As a result, it is necessary to further examine these cells, as well as the methods used for their reprogramming. The first studies on the induction of iPSCs were based on transduction of the cells with viral oncogenes. However, this approach increases the risk of insertional mutagenesis and tumor formation. Current methods to induce iPSCs rely upon elimination of permanent transgene integration, Cre-Lox mediated reprogramming, or mRNA/protein transfection [66]. Unfortunately, non-integrating methods suffer from extremely low transduction efficiency, which amounts to 0.001% in the case of adenoviruses [67]. ESCs will not be discussed here because they will likely never be used in clinical medicine due to ethical controversies. In contrast, the application of iPSCs is non-controversial. Moreover, iPSCS have another advantage over ESCs in that the genetic information derives from the patient’s genome and thus immune rejection is less probable [68]. However, the major drawback in the use of iPSCs for tissue engineering is the difficulty in obtaining a uniform cell population in the tissue of interest. This creates the danger of teratoma formation from undifferentiated cells [60]. Another drawback is the very low yield of the cells, together with the fact that they do not emerge in culture until three weeks after transduction [69]. It seems likely that iPSCs may revolutionize tissue engineering, and research on iPSCs is developing very quickly; however, this remains an emerging field and much more research is required. Potential advantages and disadvantages of the use of MSCs and iPSCs for transplantation are presented in Table 2.

Concluding remarks

Although the application of stem cells, either adult or pluripotent, should revolutionize regenerative medicine in the near future, further investigations are required before this technology can be applied in clinical practice. Better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the cell differentiation process will result in more efficient control of these processes, including chondrogenesis. At present, it is difficult to decide whether MSCs or iPSCs will be more suitable in providing cells for transplantation. Nevertheless, the development of iPSCs was a turning point in tissue engineering, which has opened up new horizons and generated a great deal of hope. The application of stem cells concerns not only the field of medicine, but also other related branches of science such as bioengineering, molecular biology and ethics, and, consequently, close collaboration between scientists from different fields. In the near future, stem cells may lead to a transition from traditional to personalized medicine. Finally, in the future, in silico models, which are widely-used in traditional engineering sectors, may also play an important role in regenerative orthopaedics research [70] because such models facilitate the optimal selection of cell type, culture conditions, and proper vectors for transfection or transduction studies and clinical procedures.

References

Cole BJ, Pascual-Garrido C, Grumet RC (2009) Surgical management of articular cartilage defects in the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91:1778–1790

Gomoll AH, Filardo G, de Girolamo L, Esprequeira-Mendes J, Marcacci M, Rodkey WG, Steadman RJ, Zaffagnini S, Kon E (2012) Surgical treatment for early osteoarthritis. Part I: cartilage repair procedures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:450–466. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1780-x

Kreuz PC, Steinwachs MR, Erggelet C, Krause SJ, Konrad G, Uhl M, Südkamp N (2006) Results after microfracture of full-thicness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarth Cart 14:1119–1125. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2006.05.003

Jones DG, Peterson L (2006) Autologous chondrocyte implantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:2501–2520

Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR (2009) Clinical efficacy of the microfracture technique for articular cartilage repair in the knee: an evidence-based systematic analysis. Am J Sports Med 37:2053–2063. doi:10.1177/0363546508328414

Gomoll AH, Probst C, Farr J, Cole BJ, Minas T (2009) The use of type I/III bi-layer collagen membrane to decrease re-operation rates for symptomatic hypertrophy after autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med 37(Suppl):20–23. doi:10.1177/0363546509348477

Cavallo C, Desando G, Facchini A, Grigolo B (2010) Chondrocytes from patients with osteoarthritis express typical extracellular matrix molecules once grown onto a three-dimensional hyaluronan-based scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res A 93:86–95. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32547

Pecina M, Jelic M, Martinovic S, Haspl M, Vukicevic S (2002) Articular cartilage repair: the role of bone morphogenetic proteins. Int Orthop 26(3):131–136. doi:10.1007/s00264-002-0338-4

Pecina M, Slobodan V (2007) Biological aspects of bone, cartilage and tendon regeneration. Int Orthop 31(6):719–720. doi:10.1007/s00264-007-0425-7

Song K, Krause C, Shi S et al (2010) Identification of a key residue mediating bone morhogenetic protein (BMP-6) resistence to noggin inhibition allows for engineered BMPs with superior agonist activity. J Biol Chem 285(16):12169–12180. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.087197

Zuo Q, Cui Q, Liu F et al (2013) Co-cultivated mesenchymal stem cells support chondrocytic differentiation of articular chondrocytes. Int Orthop 37(4):747–752. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1782-z

Toghraie FS, Chenari N, Gholipour MA, Faghih Z, Torabinejad S, Dehghani S, Ghaderi A (2011) Treatment of osteoarthritis with infrapatellar fat pad derived mesenchymal stem cells in Rabbit. Knee 18:71–75. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2010.03.001

Tuan RC (2014) Cellular signaling in developmental chondrogenesis: N-cadherin Wnts and BMP-2. J Bone Joint Surg 85-A(2):137–141

Hidaka C, Goldring M (2008) Regulatory mechanisms of chondrogenesis and implications for understanding articular cartilage homeostasis. Curr Rheumatol Rev 4:136–147. doi:10.2174/157339708785133541

Chimal-Monroy J, Rodriguez-Leon J, Montero J et al (2003) Analysis of the molecular cascade responsible for mesodermal limb chondrogenesis: sox genes and BMP signaling. Dev Biol 257:292–301. doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00066-6

Quintana L, Nieden NI, Semino CE (2009) Morphogenetic and regulatory mechanisms during developmental chondrogenesis: New paradigms for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 1:29–41. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0329

Singh P, Schwarzbauer JE (2012) Fibronectin and stem cell differentiation—lessons from chondrogenesis. J Cell Sci 125:3703–3712. doi:10.1242/jcs.095786

Goldring MB (2012) Chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and articular cartilage metabolism in health and osteoarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskel Dis 4(4):269–285. doi:10.1177/1759720X12448454

Matta C, Mobasheri A (2014) Regulation of chondrogenesis by protein kinase C: emerging new roles in calcium signalling. Cell Signal 26:979–1000. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.01.011

Keller B, Yang T, Chen Y, Munivez E, Bertin T et al (2011) Interaction of TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways during chondrogenesis. PLoS ONE 6(1):e16421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016421

Mueller MB, Fischer M, Zellner J et al (2010) Hypertrophy in mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis: effect of TGF-beta isoforms and chondrogenic conditioning. Cells Tissues Organs 192:158–166. doi:10.1159/000313399

Massagué J, Seoane J, Wotton D (2005) Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev 19:2783–2810. doi:10.1101/gad.1350705

Danišovič L, Varga I, Polák S (2012) Growth factors and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell 44:69–73. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2011.11.005

Chang SH (1998) Protein kinase C regulates chondrogenesis of mesenchymes via mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem 273:19213–19219. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.30.19213

Karamboulas K, Dranse HJ, Underhill TM (2010) Regulation of BMP-dependent chondrogenesis in early limb mesenchyme by TGF beta signals. J Cell Sci 123:2068–2076. doi:10.1242/jcs.062901

Dong S, Yang B, Guo H, Kang F (2012) Micro RNAs regulate osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 418:587–591. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.075

Eslaminejad MB, Fani N, Shahhoseini M (2013) Epigenetic regulation of osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in culture. Cell J 15:1–10

Martinovic S, Mazic S, Kisic V et al (2004) Expression of bone morphogenetic proteins in stromal cells from human bone marrow long-term culture. J Histochem Cytochem 52(9):1159–1167. doi:10.1369/jhc.4A6263.2004

Simic P, Vukicevic S (2006) Bone morphogenetic proteins: from developmental signals to tissue regeneration. EMBO Rep 8(4):327–331. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400943

Rui YF, Lui PPY, Lee YW, Chan KM (2012) Higher BMP receptor expression and BMP-2 induced osteogenic differentiation in tendon-derived stem cells compared with bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int Orthop 35(5):1099–1107. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1417-1

Furumatsu T, Ozaki T (2010) Epigenetic regulation in chondrogenesis. Acta Med Okayama 64(3):155–161

Miljkovic ND, Cooper GM, Marra KG (2008) Chondrogenesis, bone morphogenetic protein-4 and mesenchymal stem cells. Osteoarth Cart 16(10):1121–1130. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.03.003

Das SP, Ganesh S, Pradhan S, Singh D, Mohanty RN (2014) Effectiveness of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 in the management of congenital pseudoarthrotis of the tibia: a randomized controlled trial. Int Orthop 38(9):1987–1992. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2361-7

Grgurevic L, Macek B, Mercep M et al (2011) Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)1-3 enhances bone repair. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 408(1):25–31. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.109

Grgurevic L, Vukicevic S (2009) BMP-6 and mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 20(5–6):441–448. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.020

Mihelic R, Pecina M, Jelic M et al (2004) Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (Ostegenetic Proteic-1) promotes tendon graft integration in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in sheep. Am J Sports Med 32(7):1619–1625. doi:10.1177/0363546504263703

Zoricic S, Maric I, Bobinac D, Vukicevic S (2003) Expression of bone morphogenetic proteins and cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins during osteophyte formation in humans. J Anat 202(Pt 3):269–277

Beenken A, Mohammadi M (2009) The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8(3):235–253. doi:10.1038/nrd2792

Handorf AM, Li W-J (2011) Fibroblast growth factor-2 primes human mesenchymal stem cells for enhanced chondrogenesis. PLoS One 6:e22887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022887

Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K (2006) The control of chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem 1 97(1):33–44. doi:10.1002/jcb.20652

Longobardi L, Rear LO, Aakula S et al (2006) Effect of IGF-I in the chondrogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in the presence or absence of TGF- β signaling. J Bone Miner Res 21(4):626–636. doi:10.1359/JBMR.051213

Le LTT, Swingler TE, Clark IM (2013) The role of microRNAs in osteoarthritis and chondrogenesis. Arthritis Rheum 65(8):1963–1974. doi:10.1002/art.37990

Freyria AM, Mallein-Gerin F (2012) Chondrocytes or adult stem cells for cartilage repair: the indisputable role of growth factors. Injury 43(3):259–265. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.035

Mueller MB, Fischer M, Zellner J et al (2013) Effect of parathyroid hormone-related in an in vitro hypertrophy model for mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis. Int Orthop 37(5):945–951. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1800-1

Chung UI, Schipani E, McMahon AP, Kronenberg HM (2001) Indian hedgehog couples chondrogenesis to osteogenesis in endochondral bone development. J Clin Invest 107(3):295–304. doi:10.1172/JCI11706

Murtaugh LC, Chyung JH, Lassar a B (1999) Sonic hedgehog promotes somitic chondrogenesis by altering the cellular response to BMP signaling. Genes Dev 13:225–237

Evans C (2014) Using genes to facilitate the endogenous repair and regeneration of orthopaedic tissues. Int Orthop 38(9):1761–1769. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2423-x

Tiğli RS, Ghosh S, Laha MM et al (2009) Comparative chondrogenesis of human cell sources in 3D scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 3(5):348–360. doi:10.1002/term.169

Kim YI, Ryu J-S, Yeo JE, Choi YJ, Kim YS, Ko K, Koh Y-G (2014) Overexpression of TGF-β1 enhances chondrogenic differentiation and proliferation of human synovium-derived stem cells. Biochem Bioph Res Co 450(4):1593–1599. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.045

Shintani N, Siebenrock KA, Hunziker EB (2014) TGF-β1 enhances the BMP-2-induced chondrogenesis of bovine synovial explants and arrests downstream differentiation at an early stage of hypertrophy. PLoS ONE 8(1):e53086. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053086

Tsai MT, Lin DJ, Huang S et al (2012) Osteogenic differentiation is synergistically influenced by osteoinductive treatment and direct cell-cell contact between murine osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells. Int Orthop 36(1):199–205. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1259-x

Ball LM (2007) Intensive care and outcome in children undergoing haematopoietic stem cel transplantaion. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 12(3):171–174

Slovacek L, Slovackova B, Macingova Z, Jebavy L (2007) Sexuality of men treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 12(5):2770282

Ma X, Zhang X, Jia Y et al (2013) Dexamethasone induces osteogenesis via regulation of hedgehog signalling molecules in rat mesenchymal stem cells. Int Orthop 37(7):1399–1404. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1902-9

Slovacek L, Slovackova B (2007) Quality of life in oncological and hematooncological patients after hematopietic stem cell transplantation: the effect of selected psychosocial and helath aspects on quality of life: A review of the literature. Rep Pract Radiother 12(1):53–59

Mahmoudifar N, Doran PM (2012) Chondrogenesis and cartilage tissue engineering: the longer road to technology development. Trends Biotechnol 30(3):166–176. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.09.002

Chen FM, Wu LA, Zhang M et al (2011) Homing of endogenous stem/progenitor cells for in situ tissue regeneration: promises, strategies, and translational perspectives. Biomaterials 32:3189–3209. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.032

Williams AR, Hare JM (2011) Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res 109:923–940. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147

Dai L-J, Moniri MR, Zeng Z-R et al (2011) Potential implications of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 305:8–20. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.012

Giuliani N, Lisignoli G, Magnani M et al (2013) New insights into osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and their potential clinical applications for bone regeneration in pediatric orthopaedics. Stem Cells Int 2013:312501. doi:10.1155/2013/312501

Zhang Y, Wang F, Chen J et al (2012) Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells versus bone marrow nucleated cells in the treatment of chondral defects. Int Orthop 36(5):1079–1086. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1362-z

Diekman BO, Christoforou N, Willard VP et al (2012) Cartilage tissue engineering using differentiated and purified induced pluripotent stem cells. PNAS 109(47):19172–19177. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210422109

Medvedev SP, Shevchenko AI, Zakian SM (2010) Induced pluripotent stem cells : problems and advantages when applying them in regenerative medicine. Acta Nat 2(2):18–28

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M et al (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

Nakayama N, Umeda K (2011) From pluripotent stem cells to essential signalling and cellular intermediates. In: Atwood C (ed) Embryonic stem cells: the hormonal regulation of pluripotency and emryogenesis, InTech. doi:10.5772/589

Fisher MC, Ferrari D, Li Y et al (2012) The potential of human embryonic stem cells for articular cartilage repair and osteoarthritis treatment. Rheumatol Curr Res S3:004. doi:10.4172/2161-1149.S3-004

Lee AS, Tang C, Rao MS et al (2013) Tumorigenicity as a clinical hurdle for pluripotent stem cell therapies. Nat Med 19(8):998–1004. doi:10.1038/nm.3267

Cherry ABC, Daley GQ (2013) Reprogrammed cells for disease modeling and regenerative medicine. Annu Rev Med 64:277–290. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-050311-163324.REPROGRAMMED

Illich DJ, Demir N, Stojković M et al (2011) Concise review: induced pluripotent stem cells and lineage reprogramming: prospects for bone regeneration. Stem Cells 29:555–563. doi:10.1002/stem.611

Geris L (2014) Regenerative orthopaedics: in vitro, in vivo … in silico. Int Orthop 38:1771–1778. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2419-6

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Centre [grant number 2012/07/E/NZ3/01819].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Augustyniak, E., Trzeciak, T., Richter, M. et al. The role of growth factors in stem cell-directed chondrogenesis: a real hope for damaged cartilage regeneration. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 39, 995–1003 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2619-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2619-0