Abstract

The problem of asymmetric information causes a winner’s curse in many environments. Given many unsuccessful attempts to eliminate it, we hypothesize that some people ‘prefer’ the lotteries underlying the winner’s curse. Study 1 shows that after removing the hypothesized cause of error, asymmetric information, half the subjects still prefer winner’s curse lotteries, implying past efforts to de-bias the winner’s curse may have been more successful than previously recognized since subjects prefer these lotteries. Study 2 shows risk-seeking preferences only partially explain lottery preferences, while non-monetary sources of utility may explain the rest. Study 2 suggests lottery preferences are not independent of context, and offers methods to reduce the winner’s curse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

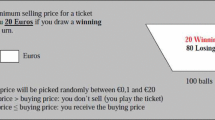

This task was first studied by Bazerman and his colleagues (Bazerman and Samuelson 1983; Samuelson and Bazerman 1985; Carroll et al. 1988; and Ball et al. 1991). Though b = 0 is a risk neutral bidder’s optimal bid, guaranteeing the seller keeps the firm, the efficient outcome requires the buyer to acquire the firm.

This work parallels the research on ultimatum games that addressed the puzzling behavior of responders who rejected positive offers. Extensive research led to the incorporation of fairness norms into utility functions (e.g., Bolton and Ockenfels 2000). Conlisk (1993) indeed presents a model that includes a ‘tiny’ bit of utility for gambling that can explain why otherwise risk-averse individuals prefer certain lotteries with negative expected value.

The size of the ceiling effect is consistent with past efforts to reduce decision error. As we discuss in the following section, researchers rarely find even a simple majority of subjects avoid the winner’s curse.

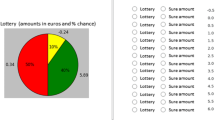

Neither mean bids (t = 0.36, p = 0.72; Kolmogrov-Smirnov non-parametric test (KS) D = 0.17, p = 0.66) nor the percent of subjects who bid 0 (t = 0.96, p = 0.34) differ significantly across task order. There are also no significant differences across task order in the number of lotteries accepted (t = 1.33, p = 0.18) or the percent of subjects who reject all lotteries (t = 1.11, p = 0.27; KS: D = 0.22, p = 0.36). The number of lotteries accepted in the ascending (7.7) and descending (8.1) orders are also not statistically different (t = 0.19, KS: D = 0.15, p = 0.85). Hence, we collapse the analysis across both task and lottery order.

Defining n = 1, 2, 3, ..., 15 does not affect our results qualitatively, where n equals the minimum number of lotteries accepted.

This analysis assumes errors are i.i.d. across each lottery choice. Since choices for each subject may not be independent, we also examined the probability q s that each subject rejects all lotteries (this analysis only assumes q s is i.i.d. across subjects). Given 37.1% (23/62) of subjects reject all lotteries, we can reject all q s < 28.3% at the 5% level (binomial distribution); if q s ≤ 28.3%, then there is a less than 5% chance we would observe 23 or more subjects reject all lotteries.

We also find the correlation between the number of lotteries accepted and mean bids (0.050) is not significant (p > 0.65).

If the subject accepts the lottery corresponding to a bid of 2 we assume the range is from 0 to 3.5 and if he accepts a lottery corresponding to a bid of 98 we assume the range is from 96.5 to 100.

For example, subject 101 accepted six lotteries corresponding to bids 42, 45, 48, 51, 54 and 57 and rejected all other lotteries. We assume this subject prefers bids on [40.5, 58.5] to bidding 0 and prefers bidding 0 to bids on [0, 40.5) and (58.5, 100], so by transitivity we assume he prefers bids on [40.5, 58.5] to all other bids. There is an 18% chance each bid is in [40.5, 58.5] if his bids are drawn from the uniform distribution on [0, 100]. Over 20 bids, the likelihood that at least one bid is in this range is 98.1% and the likelihood that at least 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 bids are in this range, respectively, are 89.8, 72.5, 49.7, 28.5, 13.6, 6.4, 1.8, 0.5 and 0.1%. In fact, subject 101 made ten bids in this predicted range. Thus, we reject at the p = 0.001 significance level that this subject suffered from decision error since his bids in the Takeover task are predicted by his revealed preferences in the Lottery task.

The importance of non-monetary utility has been demonstrated in many contexts. For instance, studies show that rejecting ultimatum game offers depends on not only the amount of the offer, but also who made the offer (Blount 1995) and what alternative offers were available (Bolton et al. 1998). Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and Tversky and Kahneman (1986) show that the framing of otherwise monetarily identical tasks can affect behavior. Huber et al. (1982) show that adding theoretically irrelevant (dominated) choices can also affect behavior. Ku et al. (2005) show that bidders who suffer from the winner’s curse may suffer from competitive arousal (i.e., receiving value from the competition to make the highest bid). Thus, there is ample evidence in the decision-making literature that people’s preferences are sensitive to many factors other than the underlying monetary payoffs.

Broader context refers to every aspect of the environment in which the decision is being made. These factors may affect how the decision is framed, what information subjects focus on and use, how much time subjects spend making the choice and so on. Our manipulations most likely affect both how the decision is framed and the information that subjects process to make their choices.

For instance, the matched lottery to the lottery that corresponded to a bid of 2 has a payoff of $0.20 if the draw is 0, a payoff of $0.05 if the draw is 1, a payoff of −$0.10 if the draw is 2 and a payoff of $0 for the remaining outcomes.

Lottery order has no significant effect on the mean number of negative lotteries subjects accept (t = 1.02, p = 0.31) or the proportion of subjects who reject all negative lotteries (t = 0.70, p = 0.49), so we collapse the analysis across order.

However, since bidding 0 guarantees the inefficient outcome that the seller keeps the firm (see footnote 1), the advice to bidders and the advice to policy-makers may differ.

References

Akerlof, George. (1970). “The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, 488–500.

Ball, Sheryl, Max Bazerman, and John Carroll. (1991). “An Evaluation of Earning in the Bilateral Winner’s Curse,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 48, 1–22.

Bazerman, Max, and William Samuelson. (1983). “I Won the Auction but Don’t Want the Prize,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 27, 618–34.

Bolton, Gary, Jordi Brandts, and Axel Ockenfels. (1998). “Measuring Motivation in the Reciprocal Responses Observed in a Dilemma Game,” Experimental Economics 1, 207–220.

Bolton, Gary, and Axel Ockenfels. (2000). “ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity and Competition,” American Economic Review 90, 166–193.

Blount, Sally. (1995). “When Social Outcomes Aren’t Fair: The Effect of Causal Attributions on Preferences,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 63, 131–144.

Capen, Edward, Robert Clapp, and William Campbell. (1971). “Competitive Bidding in High Risk Situations,” Journal of Petroleum Technology 23, 641–653.

Carroll, John, Max Bazerman, and Robin Maury. (1988). “Negotiator Cognitions: A Descriptive Approach to Negotiators’ Understanding of Their Opponents,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 41, 352–370.

Cassing, James, and Richard Douglas. (1980). “Implications of the Auction Mechanism in Baseball’s Free Agency Draft,” Southern Economic Journal 47, 110–121.

Charness, Gary, and Dan Levin. (2005). “The Origin of the Winner’s Curse,” Working Paper, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Conlisk, John. (1993). “The Utility of Gambling,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 6(3), 255–275.

Dyer, Douglas, and John Kagel. (1996). “Bidding in Common Value Auctions: How the Commercial Construction Industry Corrects for the Winner’s Curse,” Management Science 42(10), 1463–1475.

Foreman, Peter, and J. Keith Murnighan. (1996). “Learning to Avoid the Winner’s Curse,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67, 170–180.

Gilley, Otis, Gordon Karels, and Robert Leone. (1986). “Uncertainty, Experience and the ‘Winner’s Curse’ in OCS Lease Bidding,” Management Science 32(6), 673–682.

Grosskopf, Brit, Yoella Bereby-Meyer, and Max Bazerman. (2007). “On the Robustness of the Winner’s Curse Phenomenon,” Theory and Decision, (forthcoming).

Huber, Joel, John Payne, and Christopher Puto. (1982). “Adding Asymmetrically Dominated Alternatives: Violations of Regularity and the Similarity Hypothesis,” Journal of Consumer Research 9(1), 90–99.

Idson, Lorraine et al. (2003). “Overcoming Focusing Failures in Competitive Environments,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 17, 159–172.

Kagel, John. (1995). “Auctions: A Survey of Experimental Research.” In John Kagel and Alvin Roth (eds.), The Handbook of Experimental Economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, NJ.

Kagel, John, and Dan Levin. (1986). “The Winner’s Curse and Public Information in Common Value Auctions,” American Economic Review 76(5), 894–921.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. (1979). “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” Econometrica 47, 263–291.

Ku, Gillian, Deepak Malhotra, and J. Keith Murnighan. (2005). “Toward a Competitive Arousal Model of Decision-Making: A Study of Auction Fever in Live and Internet Auctions,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 96(2), 89–103.

Levis, Mario. (1990). “The Winner’s Curse Problem, Interest Costs and the Underpricing of Initial Public Offerings,” Economic Journal 100, 76–89.

Quiggin, John. (1992). “The Pioneer’s Curse: Selection Bias and Agricultural Land Degradation,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5(3), 241–246.

Roll, Richard. (1986). “The Hubris Hypothesis of Corporate Takeovers,” Journal of Business 59, 197–216.

Samuelson, William, and Max Bazerman. (1985). “Negotiation Under the Winner’s Curse.” In V. Smith (ed.), Research in Experimental Economics Vol. III. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Tor, Avishalom, and Max Bazerman. (2003). “Focusing Failures in Competitive Environments: Explaining Decision Errors in the Monty Hall Game, the Acquiring a Company Problem, and Multi-Party Ultimatums,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 16, 357–374.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. (1986). “Rational Choice and the Framing of the Decisions,” Journal of Business 59, 251–294.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garbarino, E., Slonim, R. Preferences and decision errors in the winner’s curse. J Risk Uncertainty 34, 241–257 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9013-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9013-x