Abstract

Our objective was to identify all existing systematic reviews related to counselling, case management and health promotion for people living with HIV/AIDS. For the reviews identified, we assessed the quality and local applicability to support evidence-informed policy and practice. We searched 12 electronic databases and two reviewers independently assessed the 5,398 references retrieved from our searches and included 18 systematic reviews. Each review was categorized according to the topic(s) addressed, quality appraised and summarized by extracting key messages, the year searches were last completed and the countries in which included studies were conducted. Twelve reviews address topics related to counselling and case management (mean quality score of 6.5/11). Eight reviews (mean quality score of 6/11) address topics related to health promotion (two address both domains). The findings from this overview of systematic reviews provide a useful resource for supporting the development and delivery of evidence-informed support services in community settings.

Resumen

Nuestro objetivo fue identificar todas las revisiones sistemáticas relacionadas al asesoramiento, el manejo de casos y la promoción de la salud en personas que viven con el VIH/SIDA. En las revisiones identificadas, evaluamos la calidad y aplicabilidad local para respaldar políticas y practicas informadas por la evidencia. Realizamos búsquedas en 12 bases de datos electrónicas, dos evaluadores revisaron de forma independiente las 5398 referencias identificadas e incluimos 18 revisiones sistemáticas. Cada una de las revisiones incluidas fue clasificada de acuerdo al tema presentado, valorada en terminos de su calidad, y resumida en base a la extracción de los mensajes principales, el ultimo año en que la busqueda tuvo lugar y los países incluidos en los estudios que formaron parte de la revisión. Doce revisiones abordan temas relacionados con el asesoramiento y el manejo de los casos (con un promedio de puntuación de calidad de 6.5/11). Ocho revisiones (con un promedio de puntuación de calidad de 6/11) abordan temas relacionados con la promoción de la salud (dos revisiones abordan ambos dominios). Los resultados de este compendio de revisiones sistemáticas constituyen un recurso útil para respaldar el desarrollo y la prestación de servicios de apoyo debidamente informados por la evidencia en contextos comunitarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cornerstones of community support services for people living with HIV/AIDS (PHAs) are case management, counselling and health promotion. Case management focuses on helping service users to identify their unmet needs, and linking them with the required health and social services to achieve desired outcomes [1–3]. After an initial assessment of needs, the case manager and service user collaborate on a system of referrals, monitoring, follow-up assessment and advocacy to ensure positive outcomes. Needs may vary in scope from those that are considered basic (e.g., food and shelter) to those that may be more remote but instrumental to achieving basic needs (e.g., legal services) [4]. Psycho-social counselling may be an important component of case management but is also a stand-alone intervention. Gerbert et al. [5] have noted that counselling is one of the most powerful ways to address the psycho-social aspects of HIV, which include managing risky behaviours, coping and social support, depression and treatment adherence [5]. Counselling and case management typically focus on individuals, but health promotion may have a distinctly community focus.

Health promotion is “the combination of educational and environmental supports for actions and conditions of living conducive to health” [6]; and is a “process of enabling people to take control over, and to improve, their health” [7]. This includes promoting behaviour change to achieve better health, as well as helping people and communities negotiate or dismantle the barriers to good health. Health promotion therefore includes an explicit concern with structural factors that impact health and access to health, which places community engagement and community development as intrinsic components of its mission [8].

Community-based organizations are integral to delivering these types of support services and programs to help address the increasingly complex health-related and social issues experienced by PHAs [9, 10]. These support services can impact the health of PHAs and those at risk for HIV by helping to prevent future HIV infections and addressing powerful social determinants of health such as increased social support and integration. In addition, offering HIV/AIDS support services through community-based organizations helps ensure that services are attuned to the specific needs of the communities they serve. However, most efforts towards supporting the use of research evidence have focused on clinical and prevention services, with far less effort devoted to mobilizing knowledge about effective practices in community-based organizations that provide essential on-the-ground support for PHAs.

Even though there is some debate about what constitutes “evidence” and the best approaches to effectively translate or transfer evidence to practitioners [11–13], there is general agreement that health practitioners need access to the best available research evidence to inform and support their practice [14–20]. In general, evidence-based practice (or evidence-informed decision-making) refers to practitioners’ use of standards of care whose effectiveness has been demonstrated through research evidence. In other words, decisions about care and treatment should be informed by the best available research evidence. Service providers working within health systems may improve patient, client and service user outcomes. This may then result in more efficient use of health system resources by applying care and treatment options that have been shown to be effective at improving health outcomes.

Systematic reviews are a key source of research evidence for supporting evidence-informed practice at the community level for several reasons. First, using systematic reviews is an efficient use of time for busy managers and service providers because all information on a specific topic has already been identified, selected, appraised, and synthesized in one document [21]. Research users are also less likely to be misled by findings from systematic reviews as compared to other forms of research (e.g., a single experimental study). Also, due to the gains in precision associated with synthesizing multiple studies, systematic reviews may inspire greater confidence in research findings among those who use research to support program and policy development [21]. Lastly, systematic reviews are increasingly incorporating a broader spectrum of research evidence (e.g., syntheses of qualitative evidence) [22–29] to answer questions beyond the standard effectiveness of interventions. This broader range of applications (e.g., issues related to the cost-effectiveness of interventions, and how and why interventions work) increases the relevance of systematic reviews to a wider target audience [21, 30].

To support the delivery of evidence-informed support services in community settings, we conducted an overview of systematic reviews. Our general aim was to mobilize relevant and high-quality research evidence related to counselling, case management and health promotion for PHAs. Our specific objectives were to: (1) identify and assess the quality and local applicability of systematic reviews in each of the two fundamental domains of support services (i.e., counselling and case management, and health promotion); (2) develop user-friendly summaries of the key findings and recommendations from each included systematic review: and (3) broadly disseminate the summaries to community-based organizations that service PHAs.

Methods

We searched 12 electronic databases in April 2009 using a search strategy designed to optimize the retrieval of systematic reviews (the search strategy is provided in Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article). We supplemented this by scanning the reference lists of included systematic reviews. Two teams of reviewers (LM and a research assistant, and LM and WH) independently assessed the titles and abstracts for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and a third reviewer (MGW) made a final decision where no consensus could be reached. At this initial stage of reviewing, references were included if they were either a systematic reviews or a primary research study and addressed a topic related to counselling, case management and/or health promotion for people living with HIV/AIDS. Two teams of independent reviewers (LM & WH, and LM & MGW) then assessed the references included after the initial scoping stage to identify the systematic reviews meeting our inclusion criteria.

We retrieved the full-text of all included systematic reviews and two reviewers (WH and LM) conducted a final inclusion assessment. Next, two of us (MGW and SR) conducted independent appraisals of the methodological quality of each included systematic review using the AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Reviews) instrument [31]. AMSTAR demonstrates both strong face and content validity [31], and is regarded as an optimal approach for assessing the quality of systematic reviews [32, 33]. This scale produces a quality score between 0 and 11, representing low (scores between 0 and 3), medium (scores between 4 and 7) and high (scores between 8 and 11) quality systematic reviews. We did not assess the quality of the studies included each review, which is typically conducted as part of the reviews themselves. We therefore deemed it more appropriate to provide a gauge to the quality of the methods used by each systematic review to synthesize the primary studies included in them. Using the scores of methodological quality from each review, we calculated average quality scores for each topic domain. We standardized the mean quality score by converting each score into a percentage, which we used to calculate the mean score out of 11. This standardization was necessary due to the fact that the denominators for quality appraisal scores can vary using the AMSTAR tool when a question is deemed to be ‘Not applicable’.

One of us (MGW) then categorized reviews by topic and extracted key messages, the year searches were last completed and the countries in which included studies were conducted (categorized by high and low- and middle-income countries). This work was then checked by three members of the team (WH, SR and LM) for accuracy.

Lastly, we developed user-friendly summaries for each included systematic review. We used an approach developed through a recent study with 31 executive directors and program managers of Canadian community-based organizations from the HIV/AIDS, mental health and addictions and diabetes sectors [34]. The user-friendly summaries are presented in a format that provides: (1) an outline of the topic of the review, a plain language summary and a bulleted list of key messages summary; (2) an outline of the benefits, harms and costs of the intervention, program or service evaluated in the review; and (3) relevant equity and local applicability considerations. All of the user-friendly summaries are available through an HIV/AIDS evidence service (SHARE—Synthesized HIV/AIDS Research Evidence) (http://www.hivevidence.org/SHARE/ResourcesSummaries.aspx) [35].

Results

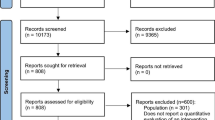

Our searches yielded 5,398 references from which we excluded 4,832 based on title and abstract review and 545 after assessing the full-text articles, leaving 18 systematic reviews (12 conducted meta-analyses) that met our inclusion criteria. The study selection process is outlined in Fig. 1.

Twelve of these reviews address topics related to counselling and case management, which have a mean quality score of 6.7/11 (see Table 1). Eight reviews address topics related to health promotion (see Tables 1, 2) which have a mean quality score of 5.9/11. Three address both domains but are presented only in Table 1 (each is identified under footnote a) but are included in the average quality calculations for both domains. Most of the systematic reviews (11 of 18) were published since 2005, all included studies from high-income countries and five include studies from low- and middle-income countries.

Counselling and Case Management Reviews

The high quality reviews (those that received between 8 and 11 on the AMSTAR scale) focused on diverse topics. They included reviews of the setting and organization of care for PHAs [36], various mental health interventions for PHAs (including group psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral interventions) [37–41], interventions to address adherence to highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) [42–44], and interventions to reduce PHA’s HIV risk behaviors [45–47]. The outcomes of these interventions varied depending on their focus. Some of the key findings from these high quality reviews highlighted their limitations. For example, Handford et al. [36] found that centralizing care in high concentration or high volume settings could lead to improved care outcomes for PHAs, but this evidence is mixed and limited to developed country settings. In addition, Handford et al. [36] found that case management was associated with improved outcomes but the limited number of studies and the varying definitions of case management leave considerable doubt about how best to implement such programs based on the studies reviewed. Another high-quality review by Himelhoch et al. [39], examined cognitive behavioral therapy, which was found to be efficacious in treating depressive symptoms among PHAs. However, the underrepresentation of women limited the generalizability of the findings [39]. Crepaz et al. [38] similarly found that PHAs who received cognitive behavioral interventions showed significant improvement in multiple mental health symptoms. However, immune functioning was not impacted, and the long-term intervention effects were uncertain. Interventions were more likely to achieve success if they incorporated stress management skills training and provided opportunities to practice skills [38].

High quality reviews about interventions to increase adherence to HAART indicated that these interventions were effective in increasing adherence. The characteristics that promote intervention success include delivery at the individual-level (as opposed to those delivered in groups), duration of 12 weeks or more, and interactive discussions about adherence [42, 43].

A high quality review by Crepaz et al. [45] about interventions to reduce PHAs risk behavior for HIV identified the following characteristics that significantly reduced unprotected sex: (1) guided by behavioural theory; (2) specifically focused on HIV transmission behaviours; (3) provided skills building; (4) delivered to individuals; (5) delivered by health-care providers or professional counselors; (6) delivered in settings where people living with HIV receive services; (7) delivered in an intensive manner; (8) delivered over a longer duration; and (9) addressed a myriad of issues relating to coping with one’s serostatus, medication adherence, and HIV risk behaviours [45].

The medium quality reviews (with scores between 4 and 7 on the AMSTAR scale) that addressed topics not covered by the high quality reviews focused on HIV testing and counselling [47] and stress management interventions [41]. Weinhardt et al. [47] found that HIV counselling and testing was effective for secondary prevention (i.e., early detection and treatment to limit disease progression and to prevent further HIV transmission) but not for primary prevention (i.e., preventing uninfected individuals from becoming infected). Scott-Sheldon et al. [41] found that stress management interventions impacted mental health symptoms, but not immunological functioning. This finding was similar to those in the high quality review by Crepaz et al. [38] which found that cognitive behavioral interventions improved mental health symptoms, but not immunological functioning.

A low-quality review [37] suggests that stigma, disclosure and self-efficacy are important factors to consider in psychosocial counselling interventions and that treatment teams should be aware of vulnerable periods in the course of HIV illness (e.g., periods of increased symptoms or pain).

Health Promotion Reviews

The systematic reviews about health promotion (that did not also address counselling and case management) are included in Table 2. Two high-quality reviews found that sustained aerobic and progressive resistance exercise strategies may lead to clinically important improvements for people living with HIV/AIDS [48, 49]. Positive physical outcomes were observed in both reviews, and the aerobic exercise review also observed positive psychological outcomes.

A medium quality review by Mills et al. [50] assessed the effectiveness of complementary and alternative treatments, and found that mental health therapies (specifically, cognitive behavioural stress management therapies) appeared to be the most promising. A medium-quality review found a positive association between housing stability and better health-related outcomes [51]. The review also found that the receipt of some form of housing assistance was associated with routine use of primary health care services [51]. The review also found that housing instability was a significant predictor of non-adherence to HAART.

Across both domains, the most common areas of focus of the reviews were mental health interventions to support PHAs [37–41], and interventions to address adherence to HIV medications [42–44, 52, 53]. The highest quality reviews with a focus on mental health evidence suggest that cognitive behavioural interventions (including group therapy) were effective at improving symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress (but not immune functioning) [38, 39]. However, as outlined by Crepaz et al. [38], there is limited evidence about the long-term impact of these types of interventions. The highest quality reviews assessing adherence to HAART [42, 43] found that participants who received an intervention were 1.5 times as likely to report 95 % adherence and 1.25 times as likely to achieve an undetectable viral load. In addition, interventions targeting practical medication management skills, those targeting individuals versus groups and those delivered over 12 weeks or more were most effective at improving adherence. The most recent review, which was of medium-quality, found that drug abuse treatment, psychological characteristics (higher self-esteem) and access to mental health treatment facilitated better adherence to HAART [53].

Discussion

Our overview was designed within the framework of helping Canadian national, provincial and local organizations meet their strategic goals related to program and policy development. The purpose of the scoping review was threefold: (1) to identify all systematic reviews related to counselling, case management and health promotion for PHAs, (2) to assess the quality and local applicability of the systematic reviews, and (3) to develop user-friendly summaries and disseminate them among program and policy decision-makers.

Principal Findings

This overview found 18 systematic reviews (12 of which conducted a meta-analysis) addressing topics related to counselling, case management and/or health promotions for people living with HIV/AIDS. All of the systematic reviews except one were of medium- or high-quality and a user-friendly summary has been developed for each to support their use by health system stakeholders. The reviews addressed topics related to: setting and organization of care for PHAs; various mental health interventions for PHAs (including group psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral interventions); interventions to address adherence to highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART); interventions to reduce PHA’s HIV risk behaviors; aerobic and progressive resistance exercise; and housing stability.

Key findings from high-quality systematic reviews found research evidence to support: centralizing PHA care in high concentration or high volume settings; cognitive behavioural interventions for reducing symptoms of depression, stress and anxiety; interventions to promote adherence (particularly those that provide practical medication management skills, target individuals are delivered over a time-period of 12 weeks or more); and the use of aerobic and progressive resistance exercise.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This overview of systematic reviews has several strengths. First, the methods used in the review are robust as they draw on validated search strategies for identifying systematic reviews and the objectives and process for selecting reviews followed an a priori protocol. Second, all of the included systematic reviews were quality appraised by two independent reviewers using a validated and commonly used tool. Lastly, in an effort to further support the use of the findings, we produced a user-friendly summary for each of the 18 included systematic reviews, which are available at (http://www.hivevidence.org/SHARE/ResourcesSummaries.aspx).

There are two main limitations to our review. First, our review is based on a search from 2009 and therefore may not include systematic reviews that have been completed since then (although we included updated versions of reviews that were originally caught in our search). Second, we conducted assessments of methodological quality of systematic reviews but not assessments of the strength of the evidence included within them. Readers should be aware that a systematic review of high methodological quality could have little utility in terms of the strength of the research evidence it includes. In other words, while a review may be well done, the studies available may be small and/or of low-quality. Lastly, though our process has made research evidence more accessible, decision-makers in community-based HIV/AIDS organizations do not have regular access to the online research databases where the full reviews are located. For example, though the user-friendly summaries provide crucial information in an accessible format, decision-makers may be unable to check the full reviews to clarify any specific issues.

Implications of the Findings

This overview of systematic reviews provides a useful resource for supporting the development and delivery of evidence-informed support services in community settings. Service providers and policy makers can draw on the set of quality appraised and synthesized systematic reviews provided in this overview to rapidly determine whether there is any high-quality synthesized research evidence available about counselling, case management or health promotion for people living with HIV/AIDS. Researchers can use this set of systematic reviews to prioritize areas where updated systematic reviews are needed and work with service providers and policymakers to identify and prioritize areas for new systematic reviews. In addition, the findings from our synthesis also highlight the need to ensure consistent methodological standards in systematic reviews. Registering titles and protocols for systematic reviews and requiring specific quality standards as part of the registration process (as is done by the Cochrane Collaboration and PROSPERO) is a promising mechanism that may help increase the overall quality of reviews.

A remaining challenge or next step is to engage decision-makers in building their capacity to effectively use the available research evidence for program development purposes. Providing information, even in the form of user-friendly summaries, is helpful and necessary. However, a larger challenge is how to use the information in the context of reviewing, renewing or developing programs and policy. This speaks to the sustainability of locating, assessing, synthesizing and disseminating research evidence to decision-makers. Future efforts may examine the sustainability of mobilizing research evidence for decision-makers.

References

Cunningham WE, Wong M, Hays RD. Case management and health-related quality of life outcomes in a national sample of persons with HIV/AIDS. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(7):840–7.

Halkitis PN, Kupprat SA, Mukherjee PP. Longitudinal associations between case management and supportive services use among black and Latina HIV-positive women in New York City. J Women’s Health. 2010;19(1):99–108.

Husbands W, Browne G, Caswell J, Buck K, Braybrook D, Roberts J, et al. Case management community care for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHAs). AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):1065–72.

Pugh GL. Exploring HIV/AIDS case management and client quality of life. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2009;8(2):202–18.

Gerbert B, Danley DW, Herzig K, Clanon K, Ciccarone D, Gilbert P, et al. Reframing “prevention with positives”: incorporating counseling techniques that improve the health of HIV-positive patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(1):19–29.

Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion as a public health strategy for the 1990s. Annu Rev Public Health. 1990;11:319–34.

World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Division of Health Promotion, Education and Communication; 1986.

Keogh P. How to be a healthy homosexual: HIV health promotion and the social regulation of gay men in the United Kingdom. J Homesex. 2008;55(4):581–605.

Mayberry RM, Daniels P, Yancey EM, Akintobi TH, Berry J, Clark N, et al. Enhancing community-based organizations’ capacity for HIV/AIDS education and prevention. Eval Program Plann. 2009;32(3):213–20.

Williams P, Narciso L, Browne G, Roberts J, Wier R, Gafni A. The prevalence, correlates, and costs of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS in Ontario: implications for service directions. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(2):119–30.

Armstrong R, Waters E, Roberts H, Oliver S, Popay J. The role and theoretical evolution of knowledge translation and exchange in public health. J Public Health. 2006;28(4):384–9.

Kirkham SR, Baumbusch JL, Schultz ASH, Anderson JM. Knowledge development and evidence-based practice: insights and opportunities from a postcolonial feminist perspective for transformative nursing practice. Adv Nurs Sci. 2007;30(1):26–40.

Victora CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):400–5.

Davis D, Davis ME, Jadad A, Perrier L, Rath D, Ryan D, et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ. 2003;327(7405):33–5.

Graham ID, Tetroe J. How to translate health research knowledge into effective healthcare action. Healthc Q. 2007;10:20–2.

Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Implementation of evidence. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009;7(3):157–8.

Kothari A, Armstrong R. Community-based knowledge translation: unexplored opportunities. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):59.

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009;181(3–4):164.

Titler MG. Nursing science and evidence-based practice. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33(3):291–5.

Wilson MG, Lavis JN, Travers R, Rourke SB. Community-based knowledge transfer and exchange: helping community-based organizations link research to action. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):33.

Lavis JN, Lomas J, Hamid M, Sewankambo NK. Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):620–8.

Dixon-Woods M, Fitzpatrick R, Roberts K. Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: opportunities and problems. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7(2):125–33.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53.

Giacomini MK. The rocky road: qualitative research as evidence. Evid Based Med. 2001;6:4–6.

Green J, Britten N. Qualitative research and evidence based medicine. BMJ. 1998;316(7139):1230–2.

Noblit G, Hare R. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

Popay J, Williams G. Qualitative research and evidence-based health care. J R Soc Med. 1998;91(suppl 35):32–7.

Sandelowski M, Trimble F, Woodard EK, Barroso J. From synthesis to script: transforming qualitative findings for use in practice. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(10):1350–70.

Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(10):1342–65.

Lavis JN. Moving forward on both systematic reviews and deliberative processes. Healthc Policy. 2006;1(2):59–63.

Shea B, Grimshaw J, Wells G, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):10–6.

Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment. Evaluation tools for COMPUS http://devccohtaca/compus/compus_pdfs/COMPUS_Evaluation_Methodology_final_epdf 2005.

Oxman A, Schunemann H, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 8. Synthesis and presentation of evidence. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4(1):20.

Wilson MG, Lavis JN. Community-based organizations and how to support their use of systematic reviews: a qualitative study. Evid Policy. 2011;7(4):449–69.

Wilson MG, Lavis JN, Grimshaw JM, Haynes RB, Bekele T, Rourke SB. Effects of an evidence service on community-based AIDS service organizations’ use of research evidence: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2011;6:52.

Handford CD, Tynan AM, Rackal JM, Glazier RH. Setting and organization of care for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD004348.

Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. Aids. 2006;20(12):1571–82.

Crepaz N, Passin WF, Herbst JH, Rama SM, Malow RM, Purcell DW, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions on HIV-positive persons’ mental health and immune functioning. Health Psychol. 2008;27(1):4–14.

Himelhoch S, Medoff DR, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(10):732–9.

Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Bussolari C, Acree M. What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(1):121–41.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder RL. Stress management interventions for HIV+ adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):129–39.

Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi AM, Tynan AM, Antoniou TA, Rourke SB, et al. Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):Art. No.: CD001442. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001442.pub2.

Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl. 1):S23–35.

Simoni JM, Montgomery A, Martin E, New M, Demas PA, Rana S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: a qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1371–83.

Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. Aids. 2006;20(2):143–57.

Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(5):642–50.

Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta- analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health 1994;89(9):1397–405.

O’Brien K, Nixon S, Glazier R, Tynan AM. Progressive resistive exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;4:CD004248.

O’Brien K, Nixon S, Tynan AM, Glazier R. Aerobic exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;8:CD001796.

Mills E, Wu P, Ernst E. Complementary therapies for the treatment of HIV: in search of the evidence. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(6):395–402.

Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(Supplement 2):85–100.

Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292(2):224–36.

Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MMF, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1242–57.

Acknowledgments

This review was funded through a Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant number KRS-92531). We would like to thank the members of our advisory committee: Simonne LeBlanc (AIDS Calgary, Canada), Michelle Gill (AIDS New Brunswick, Canada), Tanya Lary (Public Health Agency of Canada), Frank McGee (AIDS Bureau, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care) and Ken Monteith (COCQ-SIDA). We would also like to thank Joe Manson for helping with the initial review of the titles and abstracts.

Conflict of interest

Sergio Rueda is the lead author of one of the systematic reviews included in our analysis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, M.G., Husbands, W., Makoroka, L. et al. Counselling, Case Management and Health Promotion for People Living with HIV/AIDS: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. AIDS Behav 17, 1612–1625 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0283-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0283-1