Abstract

Background

Unpaid carers of older people, and older unpaid carers, experience a range of adverse outcomes. Supporting carers should therefore be a public health priority. Our understanding of what works to support carers could be enhanced if future evaluations prioritise under-researched interventions and outcomes. To support this, we aimed to: map evidence about interventions to support carers, and the outcomes evaluated; and identify key gaps in current evidence.

Methods

Evidence gap map review methods were used. Searches were carried out in three bibliographic databases for quantitative evaluations of carer interventions published in OECD high-income countries between 2013 and 2023. Interventions were eligible if they supported older carers (50 + years) of any aged recipient, or any aged carers of older people (50 + years).

Findings

205 studies reported across 208 publications were included in the evidence map. The majority evaluated the impact of therapeutic and educational interventions on carer burden and carers’ mental health. Some studies reported evidence about physical exercise interventions and befriending and peer support for carers, but these considered a limited range of outcomes. Few studies evaluated interventions that focused on delivering financial information and advice, pain management, and physical skills training for carers. Evaluations rarely considered the impact of interventions on carers’ physical health, quality of life, and social and financial wellbeing. Very few studies considered whether interventions delivered equitable outcomes.

Conclusion

Evidence on what works best to support carers is extensive but limited in scope. A disproportionate focus on mental health and burden outcomes neglects other important areas where carers may need support. Given the impact of caring on carers’ physical health, financial and social wellbeing, future research could evaluate interventions that aim to support these outcomes. Appraisal of whether interventions deliver equitable outcomes across diverse carer populations is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Across the world, the number of people living with multiple long-term conditions is growing [1, 2]. Trends in disability-free life expectancy also point to an expansion of later life disability in many countries, including the UK [3]. Together, these changes in population health are likely to result in an increased need for care– a scenario that is already predicted for England [4].

This increased demand for care presents a critical test for long-term care sectors. Many countries are already facing the challenge of insufficient long-term care funding, and poor availability and quality of services [5]. In England, reductions in funding for adult social care in the past ten years have led to an estimated £6.1 billion deficit [6]. Crucially, the expected growth in need for care in the English population will not be met by the existing supply of paid services [7].

These demographic trends point to an urgent need for a comprehensive social care policy in England. In 2021, the adult social care white paper promised reform. However, critics have highlighted a paucity of funds available to galvanise progress, especially in light of the mounting challenges faced by the sector [8]. There have been a number of changes and pauses to policy proposals leading to further delays with current intended reforms [9]. In the absence of a policy that ensures people have equitable access to timely and high-quality formal care, we can expect an unprecedented demand on friends and family to fill the care gap.

Unpaid carers have long been a critical resource in the UK care landscape. However, the current situation means that carers will occupy an even greater role in supporting people living with disability and long-term conditions. Recent analysis suggests that two-thirds of UK carers feel they have no choice about their role [10]. Although some family and friends report caring to be a rewarding experience, the reality for many is that caring can bring adverse consequences– to carers’ health, quality of life, and their social and financial wellbeing [11]. Unpaid care is a clear determinant of health; unpaid carers should therefore be a public health priority [12].

Support for carers: state of current evidence

In the absence of a social care policy for England that ensures people’s needs can be met by existing formal care provision, greater support for carers is imperative. This requires evidence about what approaches work best to support carers. Whilst evaluations of carer interventions are not in short supply, our past work reveals two key failings of this evidence [12].

First, some evaluations of carer interventions use inappropriate outcomes as an indicator of success. For example, in studies of carer respite, the outcomes evaluated are predominantly depression and anxiety. However, it is not reasonable that episodic and time-limited respite could feasibly improve long-term mental health outcomes. To identify the value of interventions for carers, evaluations must consider outcomes where meaningful impact can be expected and measured.

Second, systematic review evidence reflects a limited range of interventions for carers. Typically, past systematic reviews have focused on respite and therapeutic supports, such as counselling. Other potential supports and interventions, such as those focusing on supporting physical and financial wellbeing, are largely absent from the synthesised review literature.

In consultation with stakeholders who work across policy and practice to support carers, our work led to the creation of a logic model to depict the range of potential types of interventions that could support carers, and the expected outcomes such interventions could benefit (Table 1) [12]. Each approach may impact one or more of different aspects of carers’ lives, including their physical and/or mental health, quality of life, and their social and financial wellbeing.

Understanding what works to effectively support carers will likely be a strong feature of the future global health and social care policy research agenda. To support this, we sought to identify and map contemporary international evidence about interventions to support carers, and the outcomes evaluated. This approach offered an opportunity to identify combinations of interventions and outcomes that have been subject to little or no scientific evaluation. Such information may inform policy efforts to support carers by prioritising under-researched yet promising interventions that could be developed, trialled and evaluated.

Aims of the work

To inform future research about how best to support carers, this work aimed to: map evidence about interventions to support carers, and the outcomes evaluated; and identify key gaps in this evidence.

Methods

To address the aims of this work, we used evidence gap map methods. This approach supports the visualisation of evidence, including volume, scope and gaps [13]. The methods are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [14].

Review criteria

The review criteria are summarised in Table 2. We included evaluations of interventions for any aged carers of older people, and older carers of any aged recipients. Eligible interventions were those that aligned to the categories in Table 1. These interventions are considered relevant to support carers, and were identified through a previous review and stakeholder consultation [12]. We included interventions that targeted carers, or interventions for both care recipient and carer where there was a clear component designed for the carer. Interventions that targeted only outcomes for care recipients were not eligible.

Search strategy

A targeted search strategy was designed to identify peer-reviewed, published evaluations of interventions for carers. Searches were carried out in three bibliographic databases for the period 2013–2023:

-

MEDLINE R (OVID) 1946 to Jan Week 4 2023.

-

CINAHL (EBSCO) 1981 to February 2023.

-

PsycINFO (OVID) 1806 to January Week 4 2023.

Search terms were adapted for each database. No published filters were used, and searches were not limited by language or publication status. The search strategy applied to Medline is provided in supplementary materials. References were downloaded to, and deduplicated in EndNote (Version 20, Thomson Reuters, New York, USA). All records were then transferred to EPPI-Reviewer software for screening and coding [15].

Screening

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. At this stage, 5% of records were screened by all reviewers and discrepancies were discussed to clarify eligibility criteria. The remaining records were screened by single reviewers. The full texts of relevant records were retrieved and assessed against the review criteria, again by single reviewers.

Evaluations were eligible if they reported the following outcomes: physical health and/or mental health, carer ‘burden’, quality of life, social wellbeing, and financial wellbeing. These outcomes represent areas where carers may need support, and were informed through our previous work and stakeholder consultation [12]. Although carer ‘burden’ is a contentious concept [16], we opted to include it in this mapping review as it remains a common outcome measure for evaluating carer interventions. To capture all relevant evidence, any measures of the above outcomes were eligible.

We included randomised controlled trials, randomised trials with two intervention arms and no standard care/no intervention arm, non-randomised controlled trials, and before and after studies. Qualitative evaluations were not eligible. Such qualitative study designs typically consider process outcomes, which were not within scope for this mapping review. Studies were eligible if published in English from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) high-income countries [17]. We used this criterion to identify and map interventions that are most likely to have relevance to the UK policy and population context. To prioritise contemporary evidence, we included studies published in the last 10 years (2013–2023).

Data extraction

Studies were coded in EPPI-Reviewer to identify key study characteristics: population (carer of older people, older carer, both); intervention type; outcomes evaluated; study design; and, whether analyses considered equity of intervention outcomes by reporting effectiveness across population groups defined by the PROGRESS Plus framework [18]. Where the same study details were reported across two or more publications, we extracted data from the publication with the most detailed information.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment is not required for an evidence map [19]. However, to identify intervention-outcome combinations with the most robust evidence, we coded studies within EPPI-Reviewer to distinguish by design: randomised + control group, randomised + no control group (two or more intervention arms only), non-randomised + control group, non-randomised + no control group. For this approach, randomised studies with a control group were considered to have the lowest risk of bias. Non-randomised studies without a control group (i.e. pre post-test designs) were considered to have the highest risk of bias.

Synthesis

Study data were visualised using EPPI mapper software [15]. This method summarises the coverage and volume of evidence across interventions and outcomes, in the form of interactive maps. Map filters distinguished the volume of evidence by study population (carers of older people, older carers, or both), and by study design as an indicator of quality.

Findings

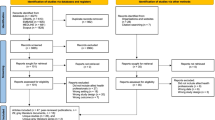

After screening, 205 studies reported across 208 publications were included (Fig. 1; Table 3) [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227]. For the remainder of this report, we refer to the 205 studies, and not the 208 publications.

The majority of studies evaluated interventions for carers of older people (n = 157). Around one fifth (n = 42) of studies evaluated interventions for both carers of older people and older carers. Few studies focused only on older carers (n = 6). The interventions evaluated typically included more than one component. The most common intervention components were therapeutic (n = 133) and educational (n = 102). A small number of studies evaluated interventions that focused on pain management for carers (n = 3), financial information and advice (n = 4), respite (n = 6) and physical skills training (n = 7). Outcomes evaluated were predominantly mental health and cognition (n = 172) and carer burden (n = 105). Just two studies evaluated carers’ financial outcomes, which included an assessment of out-of-pocket costs and self-reported financial problems.

A minority of studies (n = 8) considered equity. In these studies, the effectiveness of interventions for carers was examined by age categories (n = 3), sex (n = 2), educational level (n = 2), a measure of health status or long-term condition (n = 2), employment (n = 1), income (n = 1), urban versus rural (n = 1), area of residence (n = 1), ethnicity (n = 1), and the level of care recipients’ disability (n = 1).

Evidence gaps

Two evidence gap maps are available at https://tinyurl.com/554t5j49 and https://tinyurl.com/3578ht4t. Both maps show the volume of studies identified by intervention and outcome to highlight concentrations and gaps in evidence. Map A includes a filter for the study populations (carers of older people, older carers, both); map B a filter for study design.

The maps show a clear concentration of studies evaluating the impact of therapeutic and educational interventions on carers’ mental health and burden. By comparison, there are gaps in evidence about the effectiveness of:

-

financial information and advice interventions on all outcomes;

-

pain management interventions on all outcomes;

-

physical skills training on all outcomes.

There was also a smaller amount of evidence about physical activity and therapy interventions, befriending and peer support interventions and aids and adaptations. However, this evidence largely evaluated effectiveness using measures of carer burden and mental health. Less evidence was identified about how these interventions impact on other carer outcomes, including physical health, quality of life, and social wellbeing.

Few studies were identified that evaluated the effectiveness of respite interventions. This is likely to reflect the contemporary time window we used for this work (2013-present), rather than a complete absence of evidence. Our past work identified a large body of evidence about respite for carers published prior to 2013 and which has already been synthesised in two high-quality reviews [228, 229].

Evidence map B shows the gaps in evidence by study design. Over half of the studies used randomised designs. Most combinations of interventions and outcomes were represented by evidence from studies using both stronger (randomised) and weaker (non-randomised, pre-post test) designs. Some combinations of interventions and outcomes were represented only by stronger evidence from studies using randomisation. No combinations were represented only by weaker evidence from non-randomised studies. Pre-post test designs were most common for evaluations of therapeutic interventions for carers’ mental health (n = 43). However, there was also a similar number of studies using the strongest study design (randomised with control group) for this intervention and outcome combination.

Discussion

We mapped contemporary evidence on evaluations of carer interventions and associated outcomes. This exercise reveals a strong trend towards the evaluation of therapeutic and educational approaches to supporting carers, prioritising impacts on mental health and burden. The paucity of studies evaluating other types of interventions and outcomes means that we know little about important areas where carers may need support. For example, carers’ physical health may be compromised due to the physical demands of care tasks, or because they neglect their own health when prioritising the wellbeing of the care recipient [230, 231]. Carers also experience adverse financial outcomes, a situation that is deteriorating with the rising cost of living [232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243]. Yet our evidence map suggests that little research in the past ten years has considered what works best to support carers’ physical and financial wellbeing. Other key gaps in evidence include consideration of a range of interventions on carers’ social wellbeing and quality of life.

Most combinations of interventions and outcomes were represented by evidence from both stronger (randomised) and weaker (non-randomised, pre-post test) designs. No combination of interventions and outcomes were represented only by pre-post test designs, which we consider to be the weakest. This suggests that the primary limitation of this evidence base is the poor representation of a range of interventions and outcomes, as opposed to the strength of study designs to answer questions of effectiveness.

The gaps in evidence that we identified may reflect two scenarios in the applied health sciences. The first scenario is that an intervention may have been subject to evaluation in the period preceding the time window for the present work (2013–2023), and is no longer a focus of contemporary research. This may be the case for respite interventions, which have been comprehensively evaluated in the past [12]. Previous reviews have reported inconsistent evidence about the effectiveness of respite for carers [228, 229]. The small number of evaluations on respite identified here may reflect this pattern of earlier evidence, as well as changing research priorities and evolving approaches to supporting carers.

The second scenario is that an intervention has not yet been subject to extensive (or indeed any) evaluative study. This may be due to several reasons, including funding, feasibility considerations (such as populations being too small for rigorous evaluation), or that the intervention is new and still being developed.

Very few evaluations reported data to ascertain whether interventions produced equitable outcomes. Future studies should address this gap by exploring the extent to which any observable benefits of interventions are experienced across diverse groups of carers. This is important because outcomes for carers are socially patterned. For example, carers who are female, single, in poor health and who experience socioeconomic disadvantage are especially vulnerable to the adverse financial consequences of caring [237, 239, 240, 243, 244].

A key strength of this work is our consideration of evidence across a range of interventions and outcomes. This has enabled us to pinpoint combinations of interventions and outcomes that lack evidence, which can inform future directions in research to support carers. Comprehensive searches and robust, transparent review methods underpin the rigour of this work. Our approach did not consider grey literature, which may include local evaluations and audits that are not published. However, as researchers in this field, our expectation is that there are unlikely to be any high quality, quantitative evaluations published in non-peer reviewed sources.

Implications for policy and future research

Supporting carers is increasingly recognised as essential to the wider care system. The 2014 Care Act granted carers the right to an assessment of their needs and the right to have eligible needs met [245]. Alongside these Care Act duties, the recent passing of the Carers’ Leave Act [246] signals greater recognition of the role of carers, and their right to be supported, rather than marginalised, members of society. Finding ways to support carers is critical. Future research about what works best to support carers should consider interventions that can address outcomes beyond burden and mental health alone. Evaluating a broader range of interventions, including those based on physical activity, financial information and advice, befriending and peer support, physical skills training and pain management, would enhance the breadth of current evidence.

Third sector organisations play a key role in advocating for carers, and are likely to drive innovative approaches to delivering inclusive support. However, evaluations of these approaches can be small scale and with limited funding. Enhancing partnerships and opportunities for co-production between these organisations and academic sectors could enhance evidence about what works to support carers.

The dominance of burden and mental health outcomes may reflect a medical model approach to considering support for carers. Shifting to a more holistic social model may help to address some of the gaps in social and financial outcomes that we observed, whilst also attending to issues of equity and inclusion of diverse carer populations.

Finally, whilst qualitative process evaluations were not within the scope of this map, such methods nonetheless provide critical insight into how (and under what conditions) interventions meet carers’ needs. Thus, going forward, any evaluation of support for carers should integrate quantitative and qualitative designs to maximise the evidence base available for policy makers.

Conclusion

Contemporary evidence about what works best to support carers is vast in quantity but limited in scope. Future commissioning of research for carers may benefit from seeking evaluations of interventions with little or no evidence. Consideration of how such interventions impact a range of outcomes for carers, including their financial wellbeing and physical health, is critical. Appraisal of whether interventions deliver equitable benefits across diverse groups of carers will address an important evidence gap.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Kingston A, Robinson L, Booth H, Knapp M, Jagger C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing. 2018;47(3):374–80.

van Oostrom SH, Gijsen R, Stirbu I, Korevaar JC, Schellevis FG, Picavet HSJ, Hoeymans N. Time trends in Prevalence of Chronic diseases and Multimorbidity not only due to aging: data from General Practices and Health Surveys. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160264.

Lee J, Lau S, Meijer E, Hu P. Living longer, with or without disability? A Global and Longitudinal Perspective. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2020;75(1):162–7.

Kingston A, Comas-Herrera A, Jagger C. Forecasting the care needs of the older population in England over the next 20 years: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(9):e447–55.

Projected growth in demand for. long-term care services represents a major challenge for ageing Europe [https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/news/projected-growth-demand-long-term-care-services-represents-major-challenge-ageing-europe_en]

House of Commons. Support for unpaid carers and Carers Week 2021. 2021.

Unpaid Care in England. Future Patterns and Potential Support Strategies [https://www.lse.ac.uk/cpec/assets/documents/Economics-of-caring-2018.pdf]

The social care. White paper: not wrong, just not moving far enough in the right direction [https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2021/12/social-care-white-paper]

Future of adult social care. [https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/future-of-adult-social-care/#heading-3]

Carers Trust. PUSHED TO THE EDGE: LIFE FOR UNPAID CARERS IN THE UK. In.; 2022.

Spiers G, Stowell M, Kunonga TP, Richmond C, Beyer F, Craig D, Hanratty B. Caring for older people as a social determinant of health: a mapping review. Edited Unit NOPFPR; 2022.

Spiers GF, Liddle J, Kunonga TP, Whitehead IO, Beyer F, Stow D, Welsh C, Ramsay SE, Craig D, Hanratty B. What are the consequences of caring for older people and what interventions are effective for supporting unpaid carers? A rapid review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e046187.

Bond M. Creating interactive evidence gap maps with EPPIReviewer, EPPI-Mapper and EPPI-Visualiser. In. London: Institute of Education, University College London; 2021.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Thomas J, Graziosi S, Brunton J, Ghouze Z, O’Driscoll P, Bond M. A. K: EPPI-Reviewer: advanced software for systematic reviews, maps and evidence synthesis. EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London 2022.

Bastawrous M. Caregiver burden—A critical discussion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(3):431–41.

Office for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Country classification 2022. In.: World Bank; 2022.

O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, Evans T, Pardo Pardo J, Waters E, White H, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):56–64.

Saran A, White H. Evidence and gap maps: a comparison of different approaches. Campbell Syst Reviews. 2018;14(1):1–38.

Aguirre E, Hoare Z, Spector A, Woods RT, Orrell M. The effects of a cognitive stimulation therapy [CST] programme for people with dementia on family caregivers’ health. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:31.

Allen RS, Harris GM, Burgio LD, Azuero CB, Miller LA, Shin HJ, Eichorst MK, Csikai EL, DeCoster J, Dunn LL, et al. Can senior volunteers deliver reminiscence and creative activity interventions? Results of the legacy intervention family enactment randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(4):590–601.

Alonso-Cortes B, Seco-Calvo J, Gonzalez-Cabanach R. Physiotherapeutic intervention to promote self-care: exploratory study on Spanish caregivers of patients with dementia. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(3):500–11.

Alves S, Teixeira L, Azevedo MJ, Duarte M, Paul C. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational programme for informal caregivers of older adults. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(1):65–73.

Arai Y, Kajiwara K, Toba K, Sakurai T, Mori D, Ookubo N, Fujisaki A. A prompt and practical on-site support programme for family caregivers of persons with dementia: a preliminary uncontrolled interventional study. Psychogeriatrics:The Official J Japanese Psychogeriatr Soc. 2018;18(6):476–8.

Araújo O, Lage I, Cabrita J, Teixeira L. Training informal caregivers to care for older people after stroke: a quasi-experimental study. J Adv Nurs (John Wiley Sons Inc). 2018;74(9):2196–206.

Atkinson T, Bray J, Williamson T. You’re in a new game and you don’t know the rules: preparing carers to care. Dement (14713012). 2022;21(7):2128–43.

Austrom MG, Geros KN, Hemmerlein K, McGuire SM, Gao S, Brown SA, Callahan CM, Clark DO. Use of a multiparty web based videoconference support group for family caregivers: Innovative practice. Dementia (London) 2015, 14(5):682–690.

Bailey J, Kingston P, Alford S, Taylor L, Tolhurst E. An evaluation of cognitive stimulation therapy sessions for people with dementia and a concomitant support group for their carers. Dementia. 2017;16(8):985–1003.

Bakker TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, van der Lee J, Olde Rikkert MG, Beekman AT, Ribbe MW. Benefit of an integrative psychotherapeutic nursing home program to reduce multiple psychiatric symptoms of psychogeriatric patients and caregiver burden after six months of follow-up: a re-analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(1):34–46.

Banningh Liesbeth WAJ-W, Vernooij-Dassen Myrra JFJ, Vullings M, Prins Judith B, Rikkert Marcel GMO, Kessels Roy PC. Learning to live with a loved one with mild cognitive impairment: effectiveness of a Waiting List Controlled Trial of a Group intervention on significant others’ sense of competence and well-being. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias. 2013;28(3):228–38.

Barnes CJ, Markham C. A pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness of an individualized and cognitive behavioural communication intervention for informal carers of people with dementia: the talking sense programme. Int J Lang Communication Disorders. 2018;53(3):615–27.

Bartels SL, van Knippenberg RJM, Kohler S, Ponds RW, Myin-Germeys I, Verhey FRJ, de Vugt ME. The necessity for sustainable intervention effects: lessons-learned from an experience sampling intervention for spousal carers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(12):2082–93.

Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, Wilson NL, Morgan R, Looman WJ, McCarthy CA, Maslow K, Moye JA, Randazzo R, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377–86.

Ben M, Demers L, Fuhrer MJ, Jutai JW, Bilkey J, Plante M, DeRuyter F. Effects of a caregiver-inclusive assistive technology intervention: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):97.

Bentley TGK, Castillo D, Sadeghi N, Piber D, Carroll J, Olmstead R, Irwin MR. Costs associated with treatment of insomnia in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: a comparison of mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):231.

Berwig M, Dichter MN, Albers B, Wermke K, Trutschel D, Seismann-Petersen S, Halek M. Feasibility and effectiveness of a telephone-based social support intervention for informal caregivers of people with dementia: study protocol of the TALKING TIME project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):280.

Berwig M, Heinrich S, Spahlholz J, Hallensleben N, Brähler E, Gertz H-J. Individualized support for informal caregivers of people with dementia - effectiveness of the German adaptation of REACH II. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1–13.

Berwig M, Lessing S, Deck R. Telephone-based aftercare groups for family carers of people with dementia - results of the effect evaluation of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):177.

Birkenhager-Gillesse EG, Achterberg WP, Janus SIM, Kollen BJ, Zuidema SU. Effects of caregiver dementia training in caregiver-patient dyads: a randomized controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(11):1376–84.

Bjorge H, Kvaal K, Ulstein I. The effect of psychosocial support on caregivers’ perceived criticism and emotional over-involvement of persons with dementia: an assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):744.

Blusi M, Dalin R, Jong M. The benefits of e-health support for older family caregivers in rural areas. J Telemedicine Telecare. 2014;20(2):63–9.

Bonner Gloria J, Freels S, Ferrans C, Steffen A, Suarez Marie L, Dancy Barbara L, Watkins Yashika J, Collinge W, Hart Alysha S, Aggarwal Neelum T, et al. Advance Care Planning for African American caregivers of Relatives with dementias: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2021;38(6):547–56.

Brewster Glenna S, Epps F, Dye Clinton E, Hepburn K, Higgins Melinda K, Parker Monica L. The effect of the Great Village on psychological outcomes, burden, and mastery in African American caregivers of persons living with dementia. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(10):1059–68.

Brijoux T, Kricheldorff C, Ll MH, Bonfico S. Supporting families living with dementia in rural areas. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 2016;113(41):681–7.

Brown Arleen F, Vassar Stefanie D, Connor Karen I, Vickrey Barbara G. Collaborative care management reduces disparities in dementia care quality for caregivers with less education. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):243–51.

Brown Janet W, Chen S-l, Smith P. Evaluating a community-based family caregiver training program. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2013;25(2):76–83.

Brown KW, Coogle CL, Wegelin J. A pilot randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for caregivers of family members with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(11):1157–66.

Brunet Hannah E, Banks Sarah J, Libera A, Willingham-Jaggers M, Almén Ruth A. Training in improvisation techniques helps reduce caregiver burden and depression: innovative practice. Dement (14713012). 2021;20(1):364–72.

Bull Margaret J, Boaz L, Maadooliat M, Hagle Mary E, Gettrust L, Greene Maureen T, Holmes Sue B, Saczynski Jane S. Preparing Family caregivers to recognize delirium symptoms in older adults after elective hip or knee arthroplasty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1):e13–7.

Callan JA, Siegle GJ, Abebe K, Black B, Martire L, Schulz R, Reynolds C, rd, Hall MH. Feasibility of a pocket-PC based cognitive control intervention in dementia spousal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(6):575–82.

Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: a multi-session art-gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(2):161–8.

Camic PM, Williams CM, Meeten F. Does a ‘Singing together Group’ improve the quality of life of people with a dementia and their carers? A pilot evaluation study. Dementia. 2013;12(2):157–76.

Cash Therese V, Ekouevi Vanessa S, Kilbourn C, Lageman Sarah K. Pilot study of a mindfulness-based group intervention for individuals with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Mindfulness. 2016;7(2):361–71.

Charlesworth G, Burnell K, Crellin N, Hoare Z, Hoe J, Knapp M, Russell I, Wenborn J, Woods B, Orrell M. Peer support and reminiscence therapy for people with dementia and their family carers: a factorial pragmatic randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(11):1218–28.

Cheung DSK, Kor PPK, Jones C, Davies N, Moyle W, Chien WT, Yip ALK, Chambers S, Yu CTK, Lai CKY. The Use of Modified Mindfulness-based stress reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Program for Family Caregivers of People Living with dementia: a feasibility study. Asian Nurs Res. 2020;14(4):221–30.

Chiatti C, Rimland JM, Bonfranceschi F, Masera F, Bustacchini S, Cassetta L, Fabrizia L. Group Up-Tech r: the UP-TECH project, an intervention to support caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients in Italy: preliminary findings on recruitment and caregiving burden in the baseline population. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(6):517–25.

Clark Imogen N, Stretton-Smith Phoebe A, Baker Felicity A, Lee Young-Eun C, Tamplin J. It’s feasible to write a song: A feasibility study examining group therapeutic songwriting for people living with dementia and their family caregivers. Frontiers in Psychology Vol 11 2020, ArtID 1951 2020, 11.

Cooper C, Barber J, Griffin M, Rapaport P, Livingston G. Effectiveness of START psychological intervention in reducing abuse by dementia family carers: randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(6):881–7.

Cornelis E, Gorus E, Beyer I, Van Puyvelde K, Lieten S, Versijpt J, Vande Walle N, Aerts G, De Roover K, De Vriendt P. A retrospective study of a multicomponent rehabilitation programme for community-dwelling persons with dementia and their caregivers. Br J Occup Therapy. 2018;81(1):5–14.

Cristancho-Lacroix V, Wrobel J, Cantegreil-Kallen I, Dub T, Rouquette A, Rigaud AS. A web-based psychoeducational program for informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e117.

Cuc AV, Locke DEC, Duncan N, Fields JA, Snyder CH, Hanna S, Lunde A, Smith GE, Chandler M. A pilot randomized trial of two cognitive rehabilitation interventions for mild cognitive impairment: caregiver outcomes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(12):e180–7.

Czaja SJ, Lee CC, Perdomo D, Loewenstein D, Bravo M, Moxley P, Jh D, Schulz R. Community REACH: an implementation of an evidence-based Caregiver Program. Gerontologist. 2018;58(2):e130–7.

Czaja SJ, Loewenstein D, Schulz R, Nair SN, Perdomo D. A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21(11):1071–81.

Dam AEH, van Boxtel MPJ, Rozendaal N, Verhey FRJ, de Vugt ME. Development and feasibility of Inlife: a pilot study of an online social support intervention for informal caregivers of people with dementia. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2017;12(9):e0183386.

Damien C, Elands S, Van Den Berge D, Bier J-C. Effects of a Psychoeducational Program on caregivers of patients with dementia. Dement Geriatric Cogn Disorders. 2020;49(2):138–45.

de Moreira AF, Abalos-Medina KL, Villaverde-Gutierrez GM, Gomes de Lucena C, de Oliveira NM, Perez-Marmol A. JM: Effectiveness of two home ergonomic programs in reducing pain and enhancing quality of life in informal caregivers of post-stroke patients: A pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Disability & Health Journal 2018, 11(3):471–477.

De Cola Maria C, De Luca R, Bramanti A, Bert� F, Bramanti P, Calabr� Rocco S, Bertè F, Calabrò Rocco S. Tele-health services for the elderly: a novel southern Italy family needs-oriented model. J Telemedicine Telecare. 2016;22(6):356–62.

De Luca R, De Cola MC, Leonardi S, Portaro S, Naro A, Torrisi M, Marra A, Bramanti A, Calabro RS. How patients with mild dementia living in a nursing home benefit from dementia cafes: a case-control study focusing on psychological and behavioural symptoms and caregiver burden. Psychogeriatrics:The Official J Japanese Psychogeriatr Soc. 2021;21(4):612–7.

Dichter MN, Albers B, Trutschel D, Strobel AM, Seismann-Petersen S, Wermke K, Halek M, Berwig M. TALKING TIME: a pilot randomized controlled trial investigating social support for informal caregivers via the telephone. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):788.

DiZazzo-Miller R, Pociask Fredrick D, Adamo Diane E. The role of confidence in family caregiving for people with dementia. Phys Occup Therapy Geriatr. 2020;38(4):355–69.

DiZazzo-Miller R, Samuel Preethy S, Barnas Jean M, Welker Keith M. Addressing everyday challenges: feasibility of a Family Caregiver Training Program for people with dementia. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(2):212–20.

DiZazzo-Miller R, Winston K, Winkler Sandra L, Donovan Mary L. Family Caregiver Training Program (FCTP): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(5):1–10.

Dowling GA, Merrilees J, Mastick J, Chang VY, Hubbard E, Moskowitz JT. Life enhancing activities for family caregivers of people with frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Disease Assoc Disorders. 2014;28(2):175–81.

Droes RM, van Rijn A, Rus E, Dacier S, Meiland F. Utilization, effect, and benefit of the individualized Meeting centers Support Program for people with dementia and caregivers. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1527–53.

Ducharme F, Lachance L, Levesque L, Zarit SH, Kergoat MJ. Maintaining the potential of a psycho-educational program: efficacy of a booster session after an intervention offered family caregivers at disclosure of a relative’s dementia diagnosis. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(3):207–16.

Duggleby W, Ploeg J, McAiney C, Peacock S, Fisher K, Ghosh S, Markle-Reid M, Swindle J, Williams A, Triscott Jean A et al. Web-based intervention for family carers of persons with dementia and multiple chronic conditions (My Tools 4 Care): Pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research Vol 20(6), 2018, ArtID e10484 2018, 20(6).

Duren Paula S, Moray Juno R, Lichtenberg Peter A. Empirical evaluation of the caregivers passage through dementia on African American caregivers. Clin Gerontologist. 2023;46(1):101–10.

Dyer Suzanne M, Standfield Lachlan B, Fairhall N, Cameron Ian D, Gresham M, Brodaty H, Crotty M. Supporting community-dwelling older people with cognitive impairment to stay at home: a modelled cost analysis. Australas J Ageing. 2020;39(4):e506–14.

Evans S, Evans S, Brooker D, Henderson C, Szczesniak D, Atkinson T, Bray J, Amritpal R, Saibene FL, d’Arma A, et al. The impact of the implementation of the Dutch combined Meeting centres Support Programme for family caregivers of people with dementia in Italy, Poland and UK. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(2):280–90.

Faw Meara H, Matter Michelle M, Luzinski Cyndy H. Preliminary evaluation and implications of the SPECAL method as an intervention for informal dementia care partners. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(10):1971–8.

Fields NL, Xu L, Richardson VE, Parekh R, Ivey D, Calhoun M. Utilizing the Senior Companion Program as a platform for a culturally informed caregiver intervention: results from a mixed methods pilot study. Dementia. 2021;20(1):161–87.

Fleiner T, Dauth H, Zijlstra W, Haussermann P. A structured physical Exercise Program reduces Professional Caregiver’s Burden caused by neuropsychiatric symptoms in Acute Dementia Care: Randomized Controlled Trial results. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;74(2):429–33.

Fossey J, Charlesworth G, Fowler JA, Frangou E, Pimm TJ, Dent J, Ryder J, Robinson A, Kahn R, Aarsland D, et al. Online Education and Cognitive Behavior Therapy improve Dementia caregivers’ Mental Health: a Randomized Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(7):1403–e14091401.

Fowler CN, Kott K, Wicks MN, Rutledge C. An Interprofessional Virtual Healthcare Neighborhood: Effect on Self-Efficacy and Sleep among caregivers of older adults with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;42(11):39–47.

Fowler NR, Judge KS, Lucas K, Gowan T, Stutz P, Shan M, Wilhelm L, Parry T, Johns SA. Feasibility and acceptability of an acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for caregivers of adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):127.

Frias Cindy E, Risco E, Zabalegui A. Psychoeducational intervention on burden and emotional well-being addressed to informal caregivers of people with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20(6):900–9.

Gallego-Alberto L, Marquez-Gonzalez M, Romero-Moreno R, Cabrera I, Losada A. Pilot study of a psychotherapeutic intervention for reducing guilt feelings in highly distressed dementia family caregivers (innovative practice). Dementia. 2021;20(2):759–69.

Garand L, Morse JQ, ChiaRebecca L, Barnes J, Dadebo V, Lopez OL, Dew MA. Problem-solving therapy reduces subjective burden levels in caregivers of family members with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(7):957–65.

Garand L, Rinaldo DE, Alberth MM, Delany J, Beasock SL, Lopez OL, Reynolds CF, rd, Dew MA. Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;22(8):771–81.

Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life for Adult Child Caregivers of Persons with dementia. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(11):1179–92.

Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on Primary Subjective Stress of Adult Child Caregivers of persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2016;56(3):461–74.

Gaugler JE, Reese M, Sauld J. A pilot evaluation of Psychosocial Support for Family caregivers of relatives with dementia in long-term care: the Residential Care Transition Module. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015;8(4):161–72.

George C, Boyce M, Evans R, Ferreira N. Valuing the caregiver: a feasibility study of an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) group intervention for dementia caregivers. Working Older People: Community Care Policy Pract. 2021;25(1):94–104.

Gerritsen Debby L, Koopmans Raymond T, Walravens V, van Vliet D. Using video feedback at home in dementia care: a feasibility study. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Dement. 2019;34(3):153–62.

Gibson RH, Gander PH, Dowell AC, Jones LM. Non-pharmacological interventions for managing dementia-related sleep problems within community dwelling pairs: a mixed-method approach. Dementia. 2017;16(8):967–84.

Glueckauf RL, Kazmer MM, Nowakowski ACH, Wang Y, Thelusma N, Williams D, McGill-Scarlett C, Lampe NM, Norton-Brown T, Davis WS, et al. African American Alzheimer’s Caregiver Training and Support Project 2 (ACTS2) pilot study: outcomes analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2022;67(4):437–48.

Gonyea JG, Lopez LM, Velasquez EH. The effectiveness of a culturally sensitive cognitive behavioral group intervention for latino Alzheimer’s caregivers. Gerontologist. 2016;56(2):292–302.

Gossink F, Pijnenburg Y, Scheltens P, Pera A, Kleverwal R, Korten N, Stek M, Droes RM, Dols A. An intervention programme for caregivers of dementia patients with frontal behavioural changes: an explorative study with controlled effect on sense of competence. Psychogeriatrics:The Official J Japanese Psychogeriatr Soc. 2018;18(6):451–9.

Gresham M, Heffernan M, Brodaty H. The going to stay at Home program: combining dementia caregiver training and residential respite care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(11):1697–706.

Griffiths PC, Whitney MK, Kovaleva M, Hepburn K. Development and implementation of Tele-Savvy for Dementia caregivers: a Department of Veterans affairs Clinical Demonstration Project. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):145–54.

Gustafson DH, Gustafson DH, Cody OJ, Chih MY, Johnston DC, Asthana S. Pilot test of a computer-based system to Help Family caregivers of Dementia patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(2):541–52.

Han A, Kim Tae H, Hong H. A factorial randomized controlled trial to examine separate and combined effects of a simulation-based empathy enhancement program and a lecture-based education program on family caregivers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(10):1930–40.

Han A, Yuen HK, Jenkins J, Yun L. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) guided online for distressed caregivers of persons living with dementia. Clin Gerontologist. 2022;45(4):927–38.

Han SS, White K, Cisek E. A Feasibility Study of Individuals Living at Home with Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias: utilization of visual mapping Assistive Technology to Enhance Quality of Life and reduce Caregiver Burden. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:1885–92.

Hatch DJ, DeHart WB, Norton MC. Subjective stressors moderate effectiveness of a multi-component, multi-site intervention on caregiver depression and burden. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(4):406–13.

Hicken BL, Daniel C, Luptak M, Grant M, Kilian S, Rupper RW. Supporting caregivers of rural veterans electronically (SCORE). J Rural Health. 2017;33(3):305–13.

Hives BA, Buckler EJ, Weiss J, Schilf S, Johansen KL, Epel ES, Puterman E. The effects of Aerobic Exercise on Psychological Functioning in Family caregivers: secondary analyses of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(1):65–76.

Iris M, Berman RL, Stein S. Developing a faith-based caregiver support partnership. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):728–49.

Jain FA, Chernyak SV, Nickerson LD, Morgan S, Schafer R, Mischoulon D, Bernard-Negron R, Nyer M, Cusin C, Ramirez G, et al. Four-week Mentalizing Imagery Therapy for Family Dementia caregivers: a randomized controlled trial with neural circuit changes. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(3):180–9.

Jansen L, De Burghgraeve T, van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Schoenmakers B. Supporting an informal care group - social contacts and communication as important aspects in the psychosocial well-being of informal caregivers of older patients in Belgium. Health Soc Care Commun. 2022;30(4):1514–29.

Jeon Y-H, Krein L, Simpson Judy M, Szanton Sarah L, Clemson L, Naismith Sharon L, Low L-F, Mowszowski L, Gonski P, Norman R, et al. Feasibility and potential effects of interdisciplinary home-based reablement program (I-HARP) for people with cognitive and functional decline: a pilot trial. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(11):1916–25.

Jimenez DE, Schulz R, Perdomo D, Lee CC, Czaja SJ. Implementation of a Psychosocial Intervention Program for working caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(9):1206–27.

Joling KJ, Bosmans JE, van Marwijk HW, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, MacNeil V, van Hout JL. The cost-effectiveness of a family meetings intervention to prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of patients with dementia: a randomized trial. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2013;14:305.

Judge KS, Yarry SJ, Looman WJ, Bass DM. Improved strain and psychosocial outcomes for caregivers of individuals with dementia: findings from project ANSWERS. Gerontologist. 2013;53(2):280–92.

Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter Elizabeth A, Humber Marika B, Thompson Larry W. Helping hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontologist. 2018;41(3):209–16.

Kim H, Engström G, Theorell T, Hallinder H, Emami A. In-home online music-based intervention for stress, coping, and depression among family caregivers of persons with dementia: a pilot study. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;46:137–43.

Knapp M, King D, Romeo R, Schehl B, Barber J, Griffin M, Rapaport P, Livingston D, Mummery C, Walker Z, et al. Cost effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme in promoting the mental health of family carers of people with dementia (the START (STrAtegies for RelaTives) study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6342.

Kozlov E, McDarby M, Pagano I, Llaneza D, Owen J, Duberstein P. The feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an mHealth mindfulness therapy for caregivers of adults with cognitive impairment. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(10):1963–70.

Kunik ME, Snow AL, Wilson N, Amspoker AB, Sansgiry S, Morgan RO, Ying J, Hersch G, Stanley MA. Teaching caregivers of persons with dementia to address Pain. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;25(2):144–54.

Lappalainen P, Pakkala I, Lappalainen R, Nikander R. Supported web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Older Family caregivers (CareACT) compared to Usual Care. Clin Gerontologist. 2022;45(4):939–55.

Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, Nazarian N, Cyr NS, Khalsa DS, Lin J, Blackburn E, Irwin MR. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):57–65.

Leach MJ, Francis A, Ziaian T. Transcendental Meditation for the improvement of health and wellbeing in community-dwelling dementia caregivers [TRANSCENDENT]: a randomised wait-list controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:145.

Leone D, Carragher N, Santalucia Y, Draper B, Thompson LW, Shanley C, Mollina A, Chen L, Kyriazopoulos H, Thompson DG. A pilot of an intervention delivered to chinese- and spanish-speaking carers of people with dementia in Australia. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias. 2014;29(1):32–7.

Leroi I, Simkin Z, Hooper E, Wolski L, Abrams H, Armitage Christopher J, Camacho E, Charalambous Anna P, Collin F, Constantinidou F, et al. Impact of an intervention to support hearing and vision in dementia: the SENSE-Cog field trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(4):348–57.

Levenberg K, George DR, Lokon E. Opening minds through art: a preliminary study evaluating the effects of a creative-expression program on persons living with dementia and their primary care partners. Dementia. 2021;20(7):2412–23.

Lewis V, Bauer M, Winbolt M, Chenco C, Hanley F. A study of the effectiveness of MP3 players to support family carers of people living with dementia at home. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(3):471–9.

Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, Knapp M, Griffin M, Romeo R, King D, Livingston D, Lewis-Holmes E, Mummery C, et al. START (STrAtegies for RelaTives) study: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a manual-based coping strategy programme in promoting the mental health of carers of people with dementia. Health Technol Assess (Winchester Eng). 2014;18(61):1–242.

Livingston G, Barber JA, Kinnunen KM, Webster L, Kyle SD, Cooper C, Espie CA, Hallam B, Horsley R, Pickett J, et al. DREAMS-START (dementia RElAted Manual for Sleep; STrAtegies for RelaTives) for people with dementia and sleep disturbances: a single-blind feasibility and acceptability randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(2):251–65.

Losada A, Marquez-Gonzalez M, Romero-Moreno R, Mausbach BT, Lopez J, Fernandez-Fernandez V, Nogales-Gonzalez C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for dementia family caregivers with significant depressive symptoms: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 2015;83(4):760–72.

Luchsinger JA, Burgio L, Mittelman M, Dunner I, Levine JA, Hoyos C, Tipiani D, Henriquez Y, Kong J, Silver S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of 2 interventions for hispanic caregivers of persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(9):1708–15.

Luker K, Cooke M, Dunn L, Lloyd-Williams M, Pilling M, Todd C. Development and evaluation of an intervention to support family caregivers of people with cancer to provide home-based care at the end of life: a feasibility study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(2):154–61.

Lykens K, Moayad N, Biswas S, Reyes-Ortiz C, Singh KP. Impact of a community based implementation of REACH II program for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(2):e89290.

MacCourt P, McLennan M, Somers S, Krawczyk M. Effectiveness of a grief intervention for caregivers of people with dementia. Omega - J Death Dying. 2017;75(3):230–47.

Mackenzie CS, Wiprzycka UJ, Khatri N, Cheng J. Clinically significant effects of group cognitive behavioral therapy on spouse caregivers’ mental health and cognitive functioning: a pilot study. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2013;56(8):675–92.

Madruga M, Gozalo M, Prieto J, Rohlfs D, Gusi N. Effects of a home-based exercise program on mental health for caregivers of relatives with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;33(4):359–72.

Mallya S, Fiocco Alexandra J. The effects of mindfulness training on cognitive and psychosocial well-being among family caregivers of persons with neurodegenerative disease. Mindfulness. 2019;10(10):2026–37.

Mantel Patty-Jo K. Communication skills training for family caregivers of persons with dementia from Alzheimer’s disease. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2020, 81(12-B):No Pagination Specified.

Márquez-González M, Romero-Moreno R, Cabrera I, Olmos R, Pérez-Miguel A, Losada A, Tak-Cheng S, Haley William E. Tailored versus manualized interventions for dementia caregivers: the functional analysis-guided modular intervention. Psychol Aging. 2020;35(1):41–54.

Martin-Carrasco M, Dominguez-Panchon AI, Gonzalez-Fraile E, Munoz-Hermoso P, Ballesteros J, Group E. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention group program in the reduction of the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with dementia: the EDUCA-II randomized trial. Alzheimer Disease Assoc Disorders. 2014;28(1):79–87.

Martin-Martin Lydia M, Valenza-Demet G, Ariza-Vega P, Valenza C, Castellote-Caballero Y, Jimenez-Moleon Jose J. Effectiveness of an occupational therapy intervention in reducing emotional distress in informal caregivers of hip fracture patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(8):772–83.

Martindale-Adams J, Nichols LO, Burns R, Graney MJ, Zuber J. A trial of dementia caregiver telephone support. Can J Nurs Res. 2013;45(4):30–48.

Mavandadi S, Wray Laura O, DiFilippo S, Streim J, Oslin D. Evaluation of a Telephone-Delivered, Community-Based Collaborative Care Management Program for caregivers of older adults with dementia. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;25(9):1019–28.

Mavandadi S, Wright EM, Graydon MM, Oslin DW, Wray LO. A randomized pilot trial of a telephone-based collaborative care management program for caregivers of individuals with dementia. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):102–11.

Mbakile-Mahlanza L, van der Ploeg Eva S, Busija L, Camp C, Walker H, O’Connor Daniel W. A cluster-randomized crossover trial of montessori activities delivered by family carers to nursing home residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(3):347–58.

McAuliffe L, Wright Bradley J, Kinsella G. Memory strategy training can enhance psychoeducation outcomes for Dementia Family caregivers: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2021;93(2):722–45.

McKechnie V, Barker C, Stott J. The effectiveness of an internet support forum for carers of people with dementia: a pre-post cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e68.

McKechnie V, Barker C, Stott J. The effectiveness of an internet support forum for careers of people with dementia: a pre-post cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):415–28.

McManus K, Tao H, Jennelle PJ, Wheeler JC, Anderson GA. The effect of a performing arts intervention on caregivers of people with mild to moderately severe dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(4):735–44.

Meichsner F, Theurer C, Wilz G. Acceptance and treatment effects of an internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: a randomized-controlled trial. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(4):594–613.

Meichsner F, Topfer NF, Reder M, Soellner R, Wilz G. Telephone-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves dementia caregivers’ quality of life. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias. 2019;34(4):236–46.

Meng H, Marino VR, Conner KO, Sharma D, Davis WS, Glueckauf RL. Effects of in-person and telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapies on health services use and expenditures among African-American dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms. Ethn Health. 2021;26(6):879–92.

Menne HL, Bass DM, Johnson JD, Primetica B, Kearney KR, Bollin S, Molea MJ, Teri L. Statewide implementation of reducing disability in Alzheimer’s disease: impact on family caregiver outcomes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):626–39.

Mioshi E, McKinnon C, Savage S, O’Connor CM, Hodges JR. Improving burden and coping skills in frontotemporal dementia caregivers: a pilot study. Alzheimer Disease Assoc Disorders. 2013;27(1):84–6.

Mittelman Mary S. The DAISY psychosocial intervention does not improve outcomes in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease or their carers. Evid Based Ment Health. 2013;16(1):15–15.

Miyawaki Christina E, Tahija N, McClellan A, Chen N-W. Feasibility study of caregiver-provided life review: Implementation, adaptation, and effects on care recipients’ depressive symptoms. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health 2022:No Pagination Specified.

Monfort E, Mayol A, Lissot C, Couturier P. Evaluation of a therapeutic education program for French family caregivers of elderly people suffering from major neurocognitive disorders: preliminary study. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(4):495–506.

Montero-Cuadrado F, Galan-Martin MA, Sanchez-Sanchez J, Lluch E, Mayo-Iscar A, Cuesta-Vargas A. Effectiveness of a physical therapeutic Exercise Programme for caregivers of Dependent patients: a pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial from Spanish Primary Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource]. 2020;17(20):09.

Moore RC, Chattillion EA, Ceglowski J, Ho J, von Kanel R, Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Patterson TL, Grant I, Mausbach BT. A randomized clinical trial of behavioral activation (BA) therapy for improving psychological and physical health in dementia caregivers: results of the Pleasant events program (PEP). Behav Res Therapy. 2013;51(10):623–32.

Morris L, Innes A, Smith E, Williamson T, McEvoy P. A feasibility study of the impact of a communication-skills course, ‘Empowered conversations’, for care partners of people living with dementia. Dement (14713012). 2021;20(8):2838–50.

Mortenson WB, Demers L, Fuhrer Marcus J, Jutai Jeffrey W, Lenker J, Deruyter F. Effects of an Assistive Technology intervention on older adults with disabilities and their Informal caregivers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(4):297–306.

Noel Margaret A, Lackey E, Labi V, Bouldin Erin D. Efficacy of a Virtual Education Program for Family Caregivers of Persons Living with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86(4):1667–78.

Nogales-González C, Losada-Baltar A, Márquez-González M, Zarit Steven H. Behavioral intervention for reducing resistance in Care recipients to attending adult Day Care centers: a pilot study. Clin Gerontologist. 2014;37(5):493–505.

Olexsovich A. Interpersonal approach to dementia: An iPad-based program for caregiver education and decreasing problem behaviors in older adults with cognitive impairments. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2018, 78(8-B(E)):No Pagination Specified.

Olthof-Nefkens Maria W, Derksen Els W, Debets F, Swart Bert J, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Kalf Johanna G. Com-mens: A home-based logopaedic intervention program for communication problems between people with dementia and their caregivers - a single-group mixed-methods pilot study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2022:No Pagination Specified.

Otero P, Smit F, Cuijpers P, Torres A, Blanco V, Vazquez FL. Long-term efficacy of indicated prevention of depression in non-professional caregivers: randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2015;45(7):1401–12.

Pandey A, Littlewood K, Cooper L, McCrae J, Rosenthal M, Day A, Hernandez L. Connecting older grandmothers raising grandchildren with community resources improves family resiliency, social support, and caregiver self-efficacy. J Women Aging. 2019;31(3):269–83.

Park E, Park H, Kim Eun K. The effect of a comprehensive mobile application program (CMAP) for family caregivers of home-dwelling patients with dementia: a preliminary research. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(4):1–13.

Parker MW, Davis C, White K, Johnson D, Golden M, Zola S. Reduced care burden and improved quality of life in African American family caregivers: positive impact of personalized assistive technology. Technol Health Care. 2022;30(2):379–87.

Passoni S, Moroni L, Toraldo A, Mazza MT, Bertolotti G, Vanacore N, Bottini G. Cognitive behavioral group intervention for Alzheimer caregivers. Alzheimer Disease Assoc Disorders. 2014;28(3):275–82.

Pihet S, Kipfer S. Coping with dementia caregiving: a mixed-methods study on feasibility and benefits of a psycho-educative group program. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):209.

Pleasant Michelle L, Molinari V, Hyer K, Hobday John V, Fazio S, Cullen N. An evaluation of the CARES® Dementia Basics Program among caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(1):45–56.

Prick AE, de Lange J, Twisk J, Pot AM. The effects of a multi-component dyadic intervention on the psychological distress of family caregivers providing care to people with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(12):2031–44.

Prieto-Prieto J, Madruga M, Adsuar JC, Gonzalez-Guerrero JL, Gusi N. Effects of a home-based Exercise Program on Health-Related Quality of Life and Physical Fitness in Dementia caregivers: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource]. 2022;19(15):29.

Ptomey LT, Vidoni ED, Montenegro-Montenegro E, Thompson MA, Sherman JR, Gorczyca AM, Greene JL, Washburn RA, Donnelly JE. The feasibility of remotely delivered Exercise Session in adults with Alzheimer’s Disease and their caregivers. J Aging Phys Activity. 2019;27(5):670–7.

Puterman E, Weiss J, Lin J, Schilf S, Slusher Aaron L, Johansen Kirsten L, Epel Elissa S. Aerobic exercise lengthens telomeres and reduces stress in family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial-Curt Richter Award Paper 2018. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98:245–52.

Regan K, White F, Harvey D, Middleton Laura E. Effects of an exercise and mental activity program for people with dementia and their care partners. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(2):276–83.

Rice JD, Sperling SA, Brown DS, Mittleman MS, Manning CA. Evaluating the efficacy of TeleFAMILIES: a telehealth intervention for caregivers of community-dwelling people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(8):1613–9.

Richards AG, Tietyen AC, Jicha GA, Bardach SH, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Kryscio RJ, Abner EL. Visual Arts Education improves self-esteem for persons with dementia and reduces caregiver burden: a randomized controlled trial. Dementia. 2019;18(7–8):3130–42.

Rodriguez-Sanchez E, Patino-Alonso MC, Mora-Simon S, Gomez-Marcos MA, Perez-Penaranda A, Losada-Baltar A, Garcia-Ortiz L. Effects of a psychological intervention in a primary health care center for caregivers of dependent relatives: a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 2013;53(3):397–406.

Romero-Moreno R, Marquez-Gonzalez M, Barrera-Caballero S, Vara-Garcia C, Olazaran J, Pedroso-Chaparro MDS, Jimenez-Gonzalo L, Losada-Baltar A. Depressive and anxious comorbidity and treatment response in Family caregivers of people with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(1):395–405.

Roth AJ, Curtis AF, Rowe MA, McCrae CS. Using Telehealth to deliver cognitive behavioral treatment of Insomnia to a caregiver of a person with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Cogn Psychother. 2022;36(1):3–23.

Rotondo E, Galimberti D, Mercurio M, Giardinieri G, Forti S, Vimercati R, Borracci V, Fumagalli GG, Pietroboni AM, Carandini T, et al. Caregiver Tele-Assistance for reduction of emotional distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological support to caregivers of people with dementia: the Italian experience. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;85(3):1045–52.

Sadavoy J, Sajedinejad S, Chiu M. Evaluation of the Reitman Centre CARERS program for supporting dementia family caregivers: a pre-post intervention study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2022;34(9):827–38.

Sakurai S, Kohno Y. Effectiveness of Respite Care via Short-Stay services to support sleep in Family caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource]. 2020;17(7):02.

Samia LW, Aboueissa AM, Halloran J, Hepburn K. The Maine Savvy Caregiver Project: translating an evidence-based dementia family caregiver program within the RE-AIM Framework. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):640–61.

Sarkamo T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):634–50.

Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Dyck DG. Cognitive rehabilitation multi-family group intervention for individuals with mild cognitive impairment and their care-partners. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(9):897–908.

Seike A, Sakurai T, Sumigaki C, Takeda A, Endo H, Toba K. Verification of Educational Support intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):661–3.

Seike A, Sumigaki C, Takeuchi S, Hagihara J, Takeda A, Becker C, Toba K, Sakurai T. Efficacy of group-based multi‐component psycho‐education for caregivers of people with dementia: a randomized controlled study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(7):561–7.

Shikimoto R, Tamura N, Irie S, Iwashita S, Mimura M, Fujisawa D. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia: a single-arm pilot study. Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21(1):134–6.

Smith Paul D, Martin B, Chewning B, Hafez S, Leege E, Renken J, Smedley R. Rachel: improving health care communication for caregivers: a pilot study. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(4):433–44.

Smith R, Drennan V, Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. The impact of befriending and peer support on family carers of people living with dementia: a mixed methods study. Archives Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;76:188–95.

Snyder M, Lee A, Jenson C, Gomez G, Overath T, White H, Germain C. Personalized music in adults with dementia: effects on caregivers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):B28–28.

Song Y, McCurry Susan M, Lee D, Josephson Karen R, McGowan Sarah K, Fung Constance H, Irwin Michael R, Teng E, Alessi Cathy A, Martin Jennifer L. Development of a dyadic sleep intervention for Alzheimer’s disease patients and their caregivers. Disabil Rehabilitation: Int Multidisciplinary J. 2021;43(13):1861–71.

Sopina E, Sorensen J, Beyer N, Hasselbalch SG, Waldemar G. Cost-effectiveness of a randomised trial of physical activity in Alzheimer’s disease: a secondary analysis exploring patient and proxy-reported health-related quality of life measures in Denmark. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015217.

Sousa L, Sequeira C, Ferré-Grau C, Costa R, Pimenta S, Silva S, Graça L. Living together with Dementia—A psychoeducational group programme for family caregivers. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(4):2037–42.

Sousa L, Sequeira C, Ferré-Grau C, Graça L. Living together with dementia’: preliminary results of a training programme for family caregivers. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(1):86–95.

Steffen AM, Gant JR. A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(2):195–203.

Sundar V, Fox SW, Phillips KG. Transitions in caregiving: evaluating a person-centered approach to supporting family caregivers in the community. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):750–65.

Szczepanska-Gieracha J, Jaworska-Burzynska L, Boron-Krupinska K, Kowalska J. Nonpharmacological forms of therapy to reduce the Burden on caregivers of patients with Dementia-A pilot intervention study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource]. 2020;17(24):08.

Tamayo-Morales O, Patino‐Alonso María C, Losada A, Mora‐Simón S, Unzueta‐Arce J, González‐Sánchez S, Gómez‐Marcos Manuel A, García‐Ortiz L, Rodríguez‐Sánchez E. Behavioural intervention to reduce disruptive behaviours in adult day care centres users: a randomizsed clinical trial (PROCENDIAS study). J Adv Nurs (John Wiley Sons Inc). 2021;77(2):987–98.

Tamura NT, Shikimoto R, Nagashima K, Sato Y, Nakagawa A, Irie S, Iwashita S, Mimura M, Fujisawa D. Group multi-component programme based on cognitive behavioural therapy and positive psychology for family caregivers of people with dementia: a randomised controlled study (3 C study). Psychogeriatrics:The Official J Japanese Psychogeriatr Soc. 2023;23(1):141–56.

Tan Zaldy S, Soh M, Knott A, Ramirez K, Ercoli L, Caceres N, Yuan S, Long M, Jennings Lee A. Impact of an intensive dementia caregiver training model on knowledge and Self-Competence: the improving caregiving for Dementia Program. Volume 67. Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell; 2019. pp. 1306–9.

Tanner JA, Black BS, Johnston D, Hess E, Leoutsakos JM, Gitlin LN, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Samus QM. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based dementia care coordination intervention: effects of MIND at Home on caregiver outcomes. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(4):391–402.

Teles S, Ferreira A, Paul C. Feasibility of an online training and support program for dementia carers: results from a mixed-methods pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):173.

Teri L, Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Pike KC, McGough EL. Translating an evidence-based Multicomponent intervention for older adults with dementia and caregivers. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):548–57.

Thurn T, Voigt M, Wosch T. Pilot study of a modular music intervention: a first evaluation of the Use of Basic Elements of Music to Support Interaction between Family caregivers and their relatives with dementia. Australian J Music Therapy. 2021;32(2):1–25.

Topfer NF, Sittler MC, Lechner-Meichsner F, Theurer C, Wilz G. Long-term effects of telephone-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: findings at 3-year follow-up. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 2021;89(4):341–9.

Topfer Nils F, Wilz G. Tele.TAnDem increases the psychosocial resource utilization of dementia caregivers. GeroPsych: J Gerontopsychology Geriatric Psychiatry. 2018;31(4):173–83.

Torkamani M, McDonald L, Saez A, Kanios C, Katsanou MN, Madeley L, Limousin PD, Lees AJ, Haritou M, Jahanshahi M, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate a technology platform for the assisted living of people with dementia and their carers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(2):515–23.

Tremont G, Davis J, Papandonatos GD, Grover C, Ott BR, Fortinsky RH, Gozalo P, Bishop DS. A telephone intervention for dementia caregivers: background, design, and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(2):338–47.

Tremont G, Davis JD, Ott BR, Galioto R, Crook C, Papandonatos GD, Fortinsky RH, Gozalo P, Bishop DS. Randomized Trial of the family intervention: Telephone Tracking-Caregiver for Dementia caregivers: Use of Community and Healthcare resources. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):924–30.

Trevino KM, Stern A, Hershkowitz R, Kim SY, Li Y, Lachs M, Prigerson HG. Managing anxiety from Cancer (MAC): a pilot randomized controlled trial of an anxiety intervention for older adults with cancer and their caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(2):135–45.

Tyack C, Camic PM, Heron MJ, Hulbert S. Viewing art on a Tablet Computer: A Well-being intervention for people with dementia and their caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(7):864–94.

van Haeften-van Dijk A, Meiland Franka J, Hattink Bart J, Bakker Ton J, Droes R-M. A comparison of a community-based dementia support programme and nursing home-based day care: effects on carer needs, emotional burden and quality of life. Dementia: Int J Social Res Pract. 2020;19(8):2836–56.

Van Houtven Courtney H, Smith Valerie A, Lindquist Jennifer H, Chapman Jennifer G, Hendrix C, Hastings Susan N, Oddone Eugene Z, King Heather A, Shepherd-Banigan M, Weinberger M. Family caregiver skills training to improve experiences of Care: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JGIM: J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2114–22.

Vandepitte S, Putman K, Van Den Noortgate N, Verhaeghe S, Annemans L. Effectiveness of an in-home respite care program to support informal dementia caregivers: a comparative study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(10):1534–44.

Waelde LC, Meyer H, Thompson JM, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. Randomized Controlled Trial of Inner resources Meditation for Family Dementia caregivers. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(12):1629–41.

Warner L, Tipping L. Can Everyday Assistive technologies provide meaningful support to persons with dementia and their Informal caregivers? Evaluation of Collaborative Community Program. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(9):2022–32.

Werner P, Clay OJ, Goldstein D, Kermel-Schifmann I, Herz MK, Epstein C, Mittelman MS. Assessing an evidence-based intervention for spouse caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a community implementation of the NYUCI in Israel. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(9):1676–83.

Wharton W, Epps F, Kovaleva M, Bridwell L, Tate RC, Dorbin CD, Hepburn K. Photojournalism-based intervention reduces Caregiver Burden and Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Family caregivers. J Holist Nurs. 2019;37(3):214–24.

Whitebird RR, Kreitzer M, Crain AL, Lewis BA, Hanson LR, Enstad CJ. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. 2013;53(4):676–86.

Whitlatch Carol J, Heid Allison R, Femia Elia E, Orsulic-Jeras S, Szabo S, Zarit Steven H. The support, Health, activities, resources, and Education Program for early stage dementia: results from a randomized controlled trial. Dementia: Int J Social Res Pract. 2019;18(6):2122–39.

Wilz G, Weise L, Reiter C, Reder M, Machmer A, Soellner R. Intervention helps family caregivers of people with dementia attain own therapy goals. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias. 2018;33(5):301–8.

Xiao LD, De Bellis A, Kyriazopoulos H, Draper B, Ullah S. The Effect of a personalized dementia care intervention for caregivers from Australian minority groups. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias. 2016;31(1):57–67.

Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37(2):222–33.

Zarei S, Lakhanpal G, Sadavoy J. Tele-Mindfulness for Dementia’s Family caregivers: a Randomized Trial with a Usual Care Control Group. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2022;19(5):364–72.

Shaw C, McNamara R, Abrams K, Cannings-John R, Hood K, Longo M, Myles S, O’Mahony S, Roe B, Williams K. Systematic review of respite care in the frail elderly. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(20):1–224. iii.

Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, Golder S, Arksey H, Adamson J, Drummond M. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of respite for caregivers of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):290–9.

Health & Social Care Information Centre. Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England. 2014-15. NHS Digit 2015.

Roberts J, Young H, Andrew K, McAlpine A, Hogg J. The needs of carers who push wheelchairs. J Integr Care. 2012;20(1):23–34.

Carers UK. Heading for crisis: caught between caring and rising costs. In.: Carers UK; 2022.

Carr E, Murray ET, Zaninotto P, Cadar D, Head J, Stansfeld S, Stafford M. The Association between Informal Caregiving and Exit from Employment among older workers: prospective findings from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2018;73(7):1253–62.

Evandrou M, Glaser K. Combining work and family life: the pension penalty of caring. Ageing Soc. 2003;23:583–601.

Gomez-Leon M, Evandrou M, Falkingham J, Vlachantoni A. The dynamics of social care and employment in mid-life. Ageing Soc. 2017;39(2):381–408.

Gush K. Mothers, daughters and workers? An analysis of the relationship between women’s family caring, social class and labour market participation in the UK. Univeresy of Essex 2013, PhD Thesis.

Harris E, DA S, SH E, L C, C C. K. W-B: relationships between informal caregiving, health and work in the Health and Employment after fifty study, England. Eur J Pub Health 2020, 30.