Abstract

Background

Pharmacists in high-income countries routinely provide efficient pharmacy or pharmaceutical care services that are known to improve clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes (ECHO) of patients. However, pharmacy services in low- and middle-income countries, mainly South Asia, are still evolving and limited to providing traditional pharmacy services such as dispensing prescription medicines. This systematic review aims to assess and evaluate the impact of pharmacists’ services on the ECHO of patients in South Asian countries.

Methods

We searched PubMed/Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library for relevant articles published from inception to 20th September 2021. Original studies (only randomised controlled trials) conducted in South Asian countries (published only in the English language) and investigating the economic, clinical (therapeutic and medication safety), and humanistic impact (health-related quality of life) of pharmacists’ services, from both hospital and community settings, were included.

Results

The electronic search yielded 430 studies, of which 20 relevant ones were included in this review. Most studies were conducted in India (9/20), followed by Pakistan (6/20), Nepal (4/20) and Sri Lanka (1/20). One study showed a low risk of bias (RoB), 12 studies showed some concern, and seven studies showed a high RoB. Follow-up duration ranged from 2 to 36 months. Therapeutic outcomes such as HbA1c value and blood pressure (systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure) studied in fourteen studies were found to be reduced. Seventeen studies reported humanistic outcomes such as medication adherence, knowledge and health-related quality of life, which were found to be improved. One study reported safety and economic outcomes each. Most interventions delivered by the pharmacists were related to education and counselling of patients including disease monitoring, treatment optimisation, medication adherence, diet, nutrition, and lifestyle.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that pharmacists have essential roles in improving patients’ ECHO in South Asian countries via patient education and counselling; however, further rigorous studies with appropriate study design with proper randomisation of intervention and control groups are anticipated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pharmacists’ role has shifted from traditional dispensing-focused to pharmaceutical and clinical care services. The professional roles of pharmacists are continuously evolving and focus on helping patients achieve their optimal health outcomes. Pharmacists in many High-Income Countries (HICs) actively participate in multidisciplinary healthcare teams to deliver regular clinical pharmacy service that includes medication reconciliation and review, pharmacotherapy consultation, therapeutic drug monitoring, adverse drug reactions reporting, discharge counselling and solving other medication therapy-related problems [1, 2]. In contrast, the range of pharmacy services is limited and is not up to the standards in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as HICs [3]. However, pharmacists in LMICs have been recently reported to participate in ward rounds with other healthcare providers to document and evaluate patients' clinical progress and medication-related issues and develop and implement medication therapy management plans [4, 5].

Currently, more than 50% of all medicines are prescribed and dispensed inappropriately, and only 50% of patients take them properly globally [6, 7]. Irrational antimicrobials use, failure to complete the full course of therapy, missed doses, misuse of drugs, reuse of leftovers, use of sub-therapeutic or supra-therapeutic doses of drugs all promote the emergence of resistance, augmented therapeutic costs and even lead to the patients’ death [6, 7]. Pharmacists in LMICs have the potential to play a pivotal role in promoting rational use of medicines, regulating medication concordance, preventing and resolving drug therapy-related problems, providing drug information and improving pharmacotherapy and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients [8,9,10,11]. A systematic review of the impact of pharmacist interventions on patient outcomes, health service utilisation, and costs in LMICs found that pharmacist-delivered services may improve clinical outcomes among patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and asthma may improve their HRQOL [3]. Another systematic review that studied the 54 randomised control trials examined the impact of pharmaceutical care using patient outcomes and found that pharmaceutical care effectively improves patient short-term outcomes for several conditions, including diabetes and cardiovascular conditions [12].

Pharmacists can help physicians in selecting the appropriate medication for prescribing. Furthermore, pharmacists can contribute to understanding and reviewing patients’ adherence to prescribed medications, their dosage, and appropriate administration, which will help physicians understand the progress of medication treatment [4, 13,14,15,16]. Also, they can contribute to public health promotion via community pharmacies. For instance, tobacco control and cessation services, nutrition and healthy lifestyle management, routine immunisation, infection prevention and control, management of mental health and chronic disease care, and health and environment-related other concerns [4]. Clinical pharmacy practice is in the infant stage in South Asian countries [13, 17]. Although hospital pharmacists are expected to provide clinical pharmacy services, roles are mainly limited to dispensing and material management; on the other hand, pharmacists are reported to have education, skills and confidence in delivering clinical pharmacy services [13]. Clinical pharmacists require skills in clinical practice, critical thinking, therapeutic decision-making, and inter-professional collaborations. Experiential learning and training are essential to gain these skills [13, 17]. Clinical pharmacy services help pharmacists be more patient-focused than traditional dispensing services and gain recognition from policymakers and patients.

Postgraduate educations are key to furthering pharmacists' skills and education. In recent years, such postgraduate programmes have been established in South Asia. For example, clinical pharmacy and pharmaceutical care-related 2-year postgraduate courses were started in Nepal at Kathmandu University (from 2000), Pokhara University and Purbanchal University in 2011 and 2016, respectively, and CIST College, a private college affiliated with Pokhara University in 2017 [18]. Also, Kathmandu University commenced offering a 3-year post-baccalaureate Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) course, with two academic years of study plus a year internship in hospital speciality units for a period of 5 years (2010–2015). However, it resumed the earlier 2-year pharmaceutical care programme after 2015 [13, 18]. Similarly, a postgraduate clinical pharmacy course was initiated in India at JSS College of Pharmacy in 1996. Later, a 6-year PharmD course, with five academic years of study and a year of internship in speciality units, was also initiated in 2008, and a 5-year PharmD course was started in Pakistan in 2005 [17].

The South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC), a regional inter-government consortium of eight South Asian countries, namely Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, serves as an abode of about 26.3% (i.e., 1,940,369,612) of the world population and ranks the first in the whole Asian region [19]. The increased health-related problems and the lack of healthcare resources exponentially with the population surge, health professionals, including pharmacists, have crucial roles in promoting better health-related outcomes. However, even though the role of pharmacists has been well known, and various efforts have been made to establish clinical pharmacy programmes across South Asian countries, less number of pharmacy professionals get chances to actually demonstrate their roles to contribute toward the economic, clinical and humanistic outcomes. Also, limited studies have evaluated the impact of pharmacists’ services on economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes in South Asian countries. The present review aims to explore the existing evidence so far and assess and evaluate the impact of pharmacists’ services on economic, clinical and humanistic outcomes of patients in South Asian countries.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review evaluated the pharmacist's impact on patients’ economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes in South Asia. It was conducted in accordance with guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [20, 21] and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [22]. The review protocol was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with the registration number CRD42021273684.

Search strategy, selection criteria, data sources and extraction

The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) elements were used to formulate the research question, eligibility criteria and search strategy, where (P) patients or caregivers who received pharmacists' services; (I) pharmacists' services; (C) patients who did not receive pharmacists' services; and (O) economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes (ECHO) achieved after pharmacists' services.

The process of identifying studies was performed by (SS and AA). Five databases were searched and reviewed, including PubMed/Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library. A manual search of the reference lists of related systematic reviews, all included studies, and all additional relevant reviews was identified in the electronic search. In addition, it was checked to find further research related to this review. All references found as potentially related were conferred with a review team and deduplicated in contradiction to records already retrieved through the electronic searches.

We searched PubMed/Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library for relevant articles published from inception to 20th September 2021. Three reviewers (SS, AA and APK) independently participated in the studies' screening and selection processes; they first reviewed relevant titles and abstracts and then relevant full texts based on the eligibility criteria. A fourth reviewer (BS) settled any discrepancy in the same. Original studies [only randomised controlled trials (RCTs)] conducted in the South Asian countries (published only in the English language) and investigating the economic, clinical (therapeutic and drug safety), and humanistic impact of pharmacists, from both hospital and community settings, were included and extracted into Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Data extraction forms were pilot tested on five studies and revised as needed. The following data were extracted: primary author, publication year, country, study design, setting, sample size, duration, follow-up, characteristics of the study population (mean age and disease states), baseline characteristics of the intervention, comparison groups, the intervention (i.e., pharmacists’ services), outcomes (economic, clinical, and humanistic), and limitations or bias described in the studies. Initially, SS and RS independently extracted the data, which were reviewed by three reviewers (AA, CM and APK). The corresponding authors were contacted by email if data were not reported and/or clarity of the extracted data was required. A consensus among the reviewers resolved any divergence in extracted data. In addition, two reviewers (PT and RS) independently assessed the ROB in studies resolving differences through consensus. All the studies included were synthesised descriptively by following the PRISMA guidelines.

Eligibility criteria

Original studies (only RCTs) conducted in the South Asian countries (published only in the English language from inception to 20th September 2021) and investigating either the economic (direct medical and non-medical healthcare cost), clinical (therapeutic and drug safety), or humanistic (such as quality of life, medication adherence, knowledge, attitude, practice, patient's satisfaction) impact of pharmacists, from both hospital and community settings, were included in this systematic review. However, we excluded conference abstracts, case reports, conference papers, editorial, opinion papers, reviews, systematic reviews, and study protocols.

Definitions of health outcomes followed in this systematic review

We followed the ECHO model of the classification of health outcomes put forth by Kozma et al. [23]. We further considered the ECHO model as that clinical outcome (comparative clinical effectiveness research, improved disease or symptom control, safety and/or adverse effect of pharmacotherapy received), humanistic outcomes (patient satisfaction, medication adherence, and patients' HRQOL) and economic outcomes (pharmacoeconomics, reduction in Health Care Costs (HCCs) or utilisation, such as hospitalisations, emergency and/or clinic visits, and/or avoided drug costs) [24,25,26].

Nature of intervention

Pharmacists’ professional care includes counselling patients on rational medication use, monitoring medication adherence, monitoring drug interaction, and monitoring beneficial and adverse medication effects. The intervention group (pharmacist-led professional pharmaceutical care or intervention) was compared vs. the control group (usual pharmacy service or medical care or non-pharmaceutical or non-clinical pharmacist care).

Risk of bias assessment

The randomised studies were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB) [27, 28] independently by two authors. The ROB was categorised as ‘low’, ‘some concern’, and ‘high’ based on essential domains. The ROB was transferred to the computer-based RevMan V.5.3 to generate the ROB graph and summary. Any disagreements on judgment were resolved through the conversation between the authors. Cohen’s kappa index (κ) was used to evaluate the level of agreement between two reviewers in the study selection process, adopting a 95% confidence interval. The agreement between reviewers was based on the following established criteria: κ < 0.20 poor, κ: 0.21–0.40 fair, κ: 0.41–0.60 moderate, κ: 0.61–0.80 good and κ 0.81–1.00 very good agreement [29].

Data synthesis

Given the lack of homogeneity of study aims, participants and outcome measures, a narrative approach to data synthesis was undertaken, using text and tables aligned to each of the review objectives.

Data analysis

Due to differences in terms of intervention contents, duration, follow-ups, study designs, outcomes measuring instruments, participant demographics, types of interventions delivered by the pharmacist, and settings, data were synthesised narratively, and meta-analysis could not be performed.

Results

Study selection

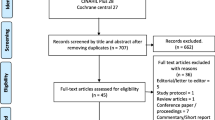

The electronic search yielded a total of 430 studies. After removing duplicates, a total of 354 titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, 39 full articles were screened, of which 20 were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

All the included studies were conducted between 2004 and 2020. The sample size included in 20 studies was 4,357 in total. People living with diabetes, hypertension, depression, asthmatic, human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C infection were included in the studies. Most studies were conducted in India (9/20) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] followed by Pakistan (6/20) [39,40,41,42,43,44], Nepal (4/20) [45,46,47,48] and Sri Lanka (1/20) [49].

Variation was found in the pharmacists' provided intervention in South Asian regions. Interventions were based on education, counselling, individualised patient care, pharmaceutical care, and interviews. Nine of the studies were conducted in the outpatient departments [34, 35, 37,38,39, 41,42,43, 47], nine were hospital-based [30,31,32, 39, 40, 44, 46, 48, 49], one in primary care setting [43] and one of the studies was conducted in community pharmacy-based service [33]. In terms of the measured outcomes, included studies reported various outcomes and the follow-up study ranged from 2 to 36 months. Therapeutic outcomes were studied in fourteen studies [30, 32,33,34,35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 47, 49]. Seventeen studies reported humanistic outcomes [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 44, 45, 47, 48], and one study reported safety and economic outcomes [41, 46]. The frequency of pharmacist intervention sessions was about 15 min for the first session, with follow-up sessions ranging from 10 to 30 min (Table 1).

Risk of bias

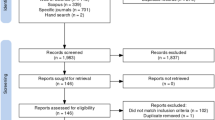

Overall, the RoB was generally variable across domains. The summaries show that one study showed a low ROB [43], twelve studies [30, 35, 36, 39, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47,48,49] showed some concern, and seven studies showed a high RoB [31,32,33,34, 37, 38, 40]. Figure 2 shows the assessments of each RoB item for each included study. Most of the common causes of bias in the included studies were participation randomisation process, missing outcome data and measurement of outcomes. Only five studies indicated concealment allocation [31, 41,42,43,44]. In addition, two studies highlighted the high-risk bias in providing more than one questionnaire for their intervention purpose to collect their various outcomes [33, 38]. Two studies [31, 33] showed a high ROB in reporting data outcomes and being influenced by the output of outcome data. Regarding the measurement of outcomes, six studies have reported a high RoB, probably influenced by the assessor’s knowledge [31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 40]. Notably, all studies reported a low RoB in selecting the findings report (Fig. 3).

Pharmacist interventions

Most interventions delivered by pharmacists were divided into education and counselling, which were further divided into education and counselling of diseases, advantages of monitoring of disease, management and treatment, medication adherence, diet, nutrition, and lifestyle. In addition, there was the provision of booklets, written materials, leaflets, and written information to aid education and counselling in some studies. Table 1 provides the details of the intervention delivered by the pharmacist in the individual included study. Similarly, Table 2 summarises the interventions delivered by the pharmacist in included studies.

Economic outcomes

Only one study has reported the economic impact of pharmacist care in the South Asian region. Upadhyay et al. reported a significant difference in direct healthcare cost from control group to two intervention groups that are at 6 months (p = 0.009, p = 0.010, respectively), 9 months (p = 0.005, p = 0.001, respectively), and 12 months (p = 0.001, p = 0.001, respectively) [46]. The direct healthcare cost was the total medical and non-medical expenses from the patient's perspective during treatment. The pharmacist-provided intervention significantly decreased the direct healthcare costs of patients in test groups during their follow-ups with a greater reduction in drug costs and investigation costs.

Clinical outcomes (therapeutic and safety outcomes)

Therapeutic outcomes

Six studies showed that pharmacists' interventions significantly reduced systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in hypertension patients compared to the control group (CG) [35, 37,38,39,40, 43]. Amer et al. in their study where pharmacist-provided pharmaceutical care to hypertensive patients, reported that pharmacist-led intervention significantly improved hypertension with SBP (131.81 ± 10.98 mmHg) and DBP (83.75 ± 6.21 mmHg) among the patients of the intervention group (IG) [40]. Javaid et al. found that individuals in the intervention arm improved their SBP (mean difference = IG: 21.1 vs. CG: + 6.1; p 0.001) and DBP (mean difference = IG: 7 vs. CG: + 4; p 0.001) more than those in the control arm [43].

Three studies indicated improvement in pre-existing diabetic conditions with a reduction in their HbA1c values [34, 43, 49]. Sriram et al. reported that the average HbA1c values decreased from 8.44 ± 0.29% to 6.73 ± 0.21% (p < 0.01) IG [34]. Similarly, Javaid et al. mentioned that the intervention group exhibited significant improvement in HbA1c outcome in both pre/post groups and control vs. intervention groups. (10.3 ± 1.3 vs. 9.7 ± 1.3, p < 0.001, I; 10.9 ± 1.7 vs. 7.7 ± 0.9, p < 0.0001) [43]. However, Yadav et al. showed improvement in asthmatic conditions where a change in the mean score of asthma control in the test group (p = 0.001) was reported, which was more significant than the control group (p = 0.099) [47]. Two studies reported improving certain lipid profile components [32, 49]. Malathy et al. showed triglycerides levels in the test group decreased considerably from 150.9 mg/dL to 140.6 mg/dL (p < 0.001) as compared to the control group(155.7 mg/dL to 148.5 mg/dL) [32]. In the test group, high density lipoprotein levels increased considerably from 34.9 mg/dL to 36.6 mg/dL (p = 0.05) [32]. Cooray et al. reported a reduction in body mass index readings, with the intervention group exhibiting 24.4 kg/m2 compared to the control group 24.9 kg/m2 after 6 months of intervention [49]. Table 3 summarises the pharmacist’s impact on patients’ outcomes regarding therapeutic, humanistic, and safety outcomes.

Safety outcome

According to Ali et al. intervention groups showed positive outcomes based on adverse drug events (8.2%) compared to the control group (10.5%) [41]. However, no statistical test was performed to create an evidence-based analysis finding [41].

Humanistic outcomes

Six studies reported improving adherence through pharmacists’ interventions [30, 39,40,41,42, 45]. In terms of knowledge, pharmacists’ interventions elevate the knowledge level among patients. The study by Amer et al. was the only study that showed improvement in both groups (intervention vs. control and pre vs. post-study) with an increase in the mean knowledge score about hypertension (18.18 ± 4.00) [40]. Regarding the quality of life, seven studies showed higher score levels [30, 34, 35, 40, 41, 44, 47]. Furthermore, the HRQOL of patients in the intervention group who received pharmaceutical care improved significantly from baseline (p 0.0001; compared to the control group (t = 6.957), in which the HRQOL was much lower (p 0.0001; t = 3.273). However, one study, Saleem et al. showed no significant impact on the HRQOL [39]. Apart from that, one study showed significant (p < 0.001) improvements in patients' satisfaction scores in the test groups [48].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted to include widespread evidence of pharmacists' services provided by the pharmacist in South Asian countries. This systematic review incorporates evidence from 20 studies in which the primary intervention provided by pharmacists/clinical pharmacists was education, counselling and monitoring on management and treatment of diseases.

Impact of pharmacists’ services on economic outcomes

Pharmacists' services were found to be significant in improving the economic outcomes of patients, which aligns with findings of other studies conducted on HICs [50, 51]. Monte et al. (2009) started a MedSense programme, a pharmacist-led patient-centred pharmacotherapy management programme in the USA and reported that cardiovascular-related costs were decreased by USD 112 at 6 months and by USD 295 at 12 months periods [50]. Wu et al. (2018), in a study conducted at three US Veteran Health Administration hospitals, reported that pharmacist-delivered care yielded a comparable improvement in cardiovascular risk factors from baseline than the conventional pharmacist-minus care, while outpatient care costs decreased among the patients with T2DM. Also, HCCs in the intervention group decreased by USD 795 below baseline levels compared to the continuous increase of USD 501 in the usual care arm [51]. When pharmacists-focused care is provided to the patients, the cost of disease management is somewhat reduced in the long run, and the patients get value for their invested expenses in health.

Impact of pharmacists’ services on clinical outcomes

This systematic review determined the significant positive impact of pharmacist’s service in improving the clinical outcomes of patients. The evidence on pharmacists’ role in providing clinical services showed that involvement of pharmacists in the disease management process leads to better health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions such as T2DM, and cardiovascular disease. Comparable findings were observed in similar studies conducted in different countries such as Nigeria, Brazil, Singapore, and Egypt [52,53,54]. David et al. (2021) reported that pharmacist-delivered care significantly improved glycemic control by reducing HbA1c levels in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria [52]. Clinical pharmacy services such as health education and health literacy empowerment, drug dispensing with counselling, medication reviews, and comprehensive medication management positively impact ECHO in the quasi-experimental before-and-after study conducted in Brazil [53]. Similarly, a systematic review on clinical pharmacy services in chronic kidney disease (CKD) also concluded that the pharmacist interventions led to improvement in creatinine clearance (CrCl), parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcium levels c in CKD patients [55]. Siaw et al. (2017) presented the indispensable role of the pharmacist as a member of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals to promote better clinical outcomes in chronic disease patients [54].

Impact of pharmacists’ services on humanistic outcomes

Pharmacist services were significant in improving patients’ humanistic outcomes, which is similar to the findings of a systematic review [56] and some European studies [57, 58]. Clinical pharmacy interventions improved glycemic control and HRQOL, and reduced adverse events (AEs) and costs of T2DM management [56]. RCT performed in community pharmacies in the Netherland documented that clinical medication services over 6 months increased EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale-measured HRQOL level by 3.4 points (from 0.94 to 5.8) among the older patients [58]. The Northern Ireland pharmacist-directed medicines optimisation clinic showed positive cost–benefit effects and patient-centred humanistic outcomes such as beliefs about pharmacotherapy, HRQOL and patient satisfaction with the intervention. These all led to a reduced frequency of emergency department visits and general practitioner consultations even during the post-discharge periods [57].

Implications for practice and research

The clinical pharmacy services in most South Asian countries are still in the developing phase. As a result, recognition of the clinical roles of pharmacists by other healthcare professionals is still a challenge [59, 60]. However, barriers could be addressed by involving pharmacists in collaborative care, building trust, demonstrating the value of pharmacists in health care teams, and strategically engaging stakeholders, including legal departments, in developing the collaborative practice process. Moreover, initiatives from the professional council at a national level to start clinical residency and certification programmes can be taken in South Asian countries to strengthen pharmacists’ ability to take better responsibility for pharmaceutical care.

Furthermore, pharmacists' continual professional development programmes must be introduced within health facilities to keep them updated with the recent findings on the healthcare systems [13, 61, 62]. Likewise, the benefits and cost-effectiveness of clinical pharmacist interventions should be well studied and implemented to make the pharmacists’ role more recognisable. Appropriately designed studies with standardised outcome measurements, longer duration of pharmacists’ intervention, interventions’ frequency and content are necessary to improve the clinical outcomes [63]. The findings of this review are believed to benefit and make the policymakers in South Asia aware of selecting relevant pharmacist interventions based on the availability of their resources.

Strengths and limitations

To date, there are numerous reviews from developed and upper-middle-income countries regarding the impact of pharmacist care. However, only one systematic review has been reported from South Asian countries, showing that pharmacists' participation in the healthcare team improves patients’ health outcomes. The findings of the current review align with this fact and suggest that the provision of clinical residency training to pharmacy graduates can play a crucial role in improving patient health outcomes and saving total healthcare costs.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations to this review. Firstly, only peer-reviewed published studies were included in this review to avoid bias, and the unpublished ones were excluded which could provide further details. Secondly, only one or a maximum of two studies were found for each outcome, so it was practically impossible to apply meta-analysis because of follow-up variation, high ROB, and differences in intervention content. Thirdly, there were variations in health outcome measurements and pharmacists' interventions. Lastly, studies were primarily conducted in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka included in the systematic review. Although RCTs were conducted in other South Asian countries, results may not be generalisable to all LMICs. Despite these limitations, we believe this review can help promote pharmacist-mediated care and pharmacy services in South Asia and thus improve patient outcomes.

Conclusion

This systematic review underpins the contribution of pharmacists’ services in South Asian countries in terms of economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes (ECHO). Interventions by the pharmacist have shown a positive impact on ECHO, but the impacts of their interventions on patients’ long-term health outcomes are yet to be explored in-depth, as most of the studies reported only the short-term outcomes. Therefore, future studies with appropriate study design, with randomisation in both interventional and control groups, are warranted to evaluate the pharmacist’s multi-dimensional roles on long-term outcomes in terms of economic (e.g., cost-effectiveness, cost-utility), clinical (e.g., improved health status), and humanistic (e.g., health-related quality of life) benefits. Also, a detailed pharmacoeconomic evaluation is required to make informed decision-making. Nevertheless, the findings of this review will be of particular interest to policymakers in countries where clinical pharmacy services are being newly implemented.

References

Jaber D, Aburuz S, Hammad EA, El-Refae H, Basheti IA. Patients’ attitude and willingness to pay for pharmaceutical care: an international message from a developing country. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(9):1177–82.

Milosavljevic A, Aspden T, Harrison J. Community pharmacist-led interventions and their impact on patients’ medication adherence and other health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(5):387–97.

Pande S, Hiller JE, Nkansah N, Bero L. The effect of pharmacist-provided non-dispensing services on patient outcomes, health service utilisation and costs in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(2):Cd010398.

Ahmed A, Saqlain M, Tanveer M, Blebil AQ, Dujaili JA, Hasan SS. The impact of clinical pharmacist services on patient health outcomes in Pakistan: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):859.

Shrestha S, Shakya S, Khatiwada AP. An urgent necessity for clinical pharmacy services in cancer care in Nepal. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1392–3.

Bbosa GS, Wong G, Kyegombe DB, Ogwal-Okeng J. Effects of intervention measures on irrational antibiotics/antibacterial drug use in developing countries. 2014.

Melku L, Wubetu M, Dessie B. Irrational drug use and its associated factors at Debre Markos Referral Hospital’s outpatient pharmacy in East Gojjam, Northwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211025144.

Pizetta B, Raggi LG, Rocha KSS, Cerqueira-Santos S, de Lyra-Jr DP, Dos Santos Júnior GA. Does drug dispensing improve the health outcomes of patients attending community pharmacies? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):764.

Silva HM, Gonzaga do Nascimento MM, de Morais Neves C, Oliveira IV, Cipolla CM, Batista de Oliveira GC, de Almeida Nascimento Y, Ramalhode Oliveira D. Service blueprint of comprehensive medication management: a mapping for outpatient clinics. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(10):1727–36.

Shrestha S, Khatiwada AP, Gyawali S, Shankar PR, Palaian S. Overview, challenges and future prospects of drug information services in Nepal: a reflective commentary. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:287.

Shrestha S, Danekhu K, Kc B, Palaian S, Ibrahim MIM. Bibliometric analysis of adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance research activities in Nepal. Therapeutic Adv Drug Safety. 2020;11:2042098620922480.

Babar Z-U-D, Kousar R, Murtaza G, Azhar S, Khan SA, Curley L. Randomized controlled trials covering pharmaceutical care and medicines management: a systematic review of literature. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(6):521–39.

Shrestha S, Shakya D, Palaian S. Clinical pharmacy education and practice in Nepal: a glimpse into present challenges and potential solutions. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:541–8.

Shrestha S, Kc B, Blebil AQ, Teoh SL. Pharmacist involvement in cancer pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2022.

Shrestha S, Shrestha S, Khanal S. Polypharmacy in elderly cancer patients: challenges and the way clinical pharmacists can contribute in resource-limited settings. Aging Med. 2019;2(1):42–9.

Shrestha S, Shrestha S, Palaian S. Can clinical pharmacists bridge a gap between medical oncologists and patients in resource-limited oncology settings? An experience in Nepal. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;25(3):765–8.

Bhagavathula AS, Sarkar BR, Patel I. Clinical pharmacy practice in developing countries: focus on India and Pakistan. Arch Pharma Pract. 2014;5(2):91–4.

Shrestha S, Shrestha S, Sapkota B, Shakya R, Roien R, Ibrahim MIM. Reintroduction of post-baccalaureate doctor of pharmacy (PharmD, Post-Bac) program in Nepal: exploration of the obstacles and solutions to move forward. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:159.

Worldometer. Southern Asia Population. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/southern-asia-population/.

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, Thomas J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142.

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372.

Kozma CM. Outcomes research and pharmacy practice. Am Pharm. 1995;7:35–41.

Cheng Y, Raisch DW, Borrego ME, Gupchup GV. Economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes (ECHOs) of pharmaceutical care services for minority patients: a literature review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(3):311–29.

Pizetta B, Raggi LG, Rocha KSS, Cerqueira-Santos S, de Lyra-Jr DP, dos Santos Júnior GA. Does drug dispensing improve the health outcomes of patients attending community pharmacies? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMPC). Outcomes Research https://www.amcp.org/about/managed-care-pharmacy-101/concepts-managed-care-pharmacy/outcomes-research.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343: d5928.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366: l4898.

Marston L. Introductory statistics for health and nursing using SPSS: Sage Publications; 2010.

Ramanath K, Balaji D, Nagakishore C, Kumar SM, Bhanuprakash M. A study on impact of clinical pharmacist interventions on medication adherence and quality of life in rural hypertensive patients. J Young Pharm. 2012;4(2):95–100.

Ponnusankar S, Surulivelrajan M, Anandamoorthy N, Suresh B. Assessment of impact of medication counseling on patients’ medication knowledge and compliance in an outpatient clinic in South India. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54(1):55–60.

Malathy R, Narmadha M, Jose MA, Ramesh S, Babu ND. Effect of a diabetes counseling programme on knowledge, attitude and practice among diabetic patients in Erode district of South India. J Young Pharm. 2011;3(1):65–72.

Adepu R, Rasheed A, Nagavi B. Effect of patient counseling on quality of life in type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in two selected South Indian community pharmacies: a study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2007;69(4):519.

Sriram S, Chack LE, Ramasamy R, Ghasemi A, Ravi TK, Sabzghabaee AM. Impact of pharmaceutical care on quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(Suppl1):S412.

Wal P, Wal A, Bhandari A, Pandey U, Rai AK. Pharmacist involvement in the patient care improves outcome in hypertension patients. J Res Pharm Pract. 2013;2(3):123.

Abdulsalim S, Unnikrishnan MK, Manu MK, Alrasheedy AA, Godman B, Morisky DE. Structured pharmacist-led intervention programme to improve medication adherence in COPD patients: a randomized controlled study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14(10):909–14.

Goruntla N, Mallela V, Nayakanti D. Effect of pharmacist directed counselling services on knowledge, attitude, and practice (kap) and blood pressure control in hypertensive patients: a randomized control trial. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2019;10:5109–16.

Adepu R, Ari SM. Influence of structured patient education on therapeutic outcomes in diabetes and hypertensive patients. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2010;3(3):174–8.

Saleem F, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Ul Haq N, Farooqui M, Aljadhay H, Ahmad FUD. Pharmacist intervention in improving hypertension-related knowledge, treatment medication adherence and health-related quality of life: a non-clinical randomized controlled trial. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1270–81.

Amer M, Rahman NU, Nazir R, Ur S, Raza A, Riaz H, Sultana M, Sadeeqa S. Impact of pharmacist’s intervention on disease related knowledge, medication adherence, HRQoL and control of blood pressure among hypertensive patients. Pakistan J Pharm Sci. 2018.

Ali S, Ali M, Paudyal V, Rasheed F, Ullah S, Haque S, Ur-Rehman T. A randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of clinical pharmacy interventions on treatment outcomes, health related quality of life and medication adherence among hepatitis C patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:2089.

Chatha ZF, Rashid U, Olsen S, Din F, Khan A, Nawaz K, Gan SH, Khan GM. Pharmacist-led counselling intervention to improve antiretroviral drug adherence in Pakistan: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Javaid Z, Imtiaz U, Khalid I, Saeed H, Khan RQ, Islam M, Saleem Z, Sohail MF, Danish Z, Batool F. A randomized control trial of primary care-based management of type 2 diabetes by a pharmacist in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Saeed A, Sughra U, Noor F, Ahmad I, Farooq U, Nazir T. Impact of pharmacist led pharmaceutical care on patient medication therapy using prompt-qol in tertiary care hospital: a randomized controlled trial. J Appl Pharm. 2021;13:1–13.

Marasine NR, Sankhi S, Lamichhane R. Impact of pharmacist intervention on medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes among depressed patients in a private psychiatric hospital of Nepal: a randomised controlled trial. Hospital Pharmacy 2020:0018578720970465.

Upadhyay DK, Ibrahim MIM, Mishra P, Alurkar VM, Ansari M. Does pharmacist-supervised intervention through pharmaceutical care program influence direct healthcare cost burden of newly diagnosed diabetics in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal: a non-clinical randomised controlled trial approach. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2016;24(1):1–10.

Yadav A, Thapa P. Pharmacist led intervention on inhalation technique among asthmatic patients for improving quality of life in a private hospital of Nepal. Pulmon Med. 2019;2019:1.

Upadhyay DK, Ibrahim MIM, Mishra P, Alurkar VM. A non-clinical randomised controlled trial to assess the impact of pharmaceutical care intervention on satisfaction level of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–10.

Bulathsinghalage Poornima Reshamie C, Hana M, Eisha Indumani W, Patrick Anthony B, Manilka S: New pharmacist role in diabetes education in Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional descriptive randomized step-up study. 2018.

Monte SV, Slazak EM, Albanese NP, Adelman M, Rao G, Paladino JA. Clinical and economic impact of a diabetes clinical pharmacy service program in a university and primary care-based collaboration model. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(2):200–8.

Wu WC, Taveira TH, Jeffery S, Jiang L, Tokuda L, Musial J, Cohen LB, Uhrle F. Costs and effectiveness of pharmacist-led group medical visits for type-2 diabetes: a multi-center randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4): e0195898.

David EA, Soremekun RO, Abah IO, Aderemi-Williams RI. Impact of pharmacist-led care on glycaemic control of patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial in Nigeria. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2021;19(3):2402.

Dos Santos Júnior GA, Silva ROS, Onozato T, Silvestre CC, Rocha KSS, Araújo EM, de Lyra-Jr DP. Implementation of clinical pharmacy services using problematization with Maguerez Arc: a quasi-experimental before-after study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(2):391–403.

Nagib R, Abdul-Latif M, Sakoury HS, Elrggal ME, Cheema E, Elnaem MH, El-Fass KA. Assessing the impact of clinical pharmacy services on the healthcare outcomes of patients attending an outpatient haemodialysis unit in a rural hospital in Egypt: a quasi-experimental study. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2021;12(3):326–31.

Al Raiisi F, Stewart D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Salgado TM, Mohamed MF, Cunningham S. Clinical pharmacy practice in the care of Chronic Kidney Disease patients: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(3):630–66.

Desse TA, Vakil K, Mc Namara K, Manias E. Impact of clinical pharmacy interventions on health and economic outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2021;38(6): e14526.

Odeh M, Scullin C, Hogg A, Fleming G, Scott MG, McElnay JC. A novel approach to medicines optimisation post-discharge from hospital: pharmacist-led medicines optimisation clinic. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(4):1036–49.

Verdoorn S, Kwint HF, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. Effects of a clinical medication review focused on personal goals, quality of life, and health problems in older persons with polypharmacy: a randomised controlled trial (DREAMeR-study). PLoS Med. 2019;16(5): e1002798.

Acheampong F, Anto BP. Perceived barriers to pharmacist engagement in adverse drug event prevention activities in Ghana using semi-structured interview. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:361–361.

Atif M, Razzaq W, Mushtaq I, Malik I, Razzaq M, Scahill S, Babar Z-U-D. Pharmacy services beyond the basics: a qualitative study to explore perspectives of pharmacists towards basic and enhanced pharmacy services in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2379.

Shrestha S, Sharma S, Bhasima R, Kunwor P, Adhikari B, Sapkota B. Impact of an educational intervention on pharmacovigilance knowledge and attitudes among health professionals in a Nepal cancer hospital. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):179.

Batista JPB, Torre C, Sousa Lobo JM, Sepodes B. A review of the continuous professional development system for pharmacists. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):3.

Presley B, Groot W, Pavlova M. Pharmacy-led interventions to improve medication adherence among adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(9):1057–67.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for conducting this research work. The authors also acknowledge the support from the University of Birmingham to cover the open access fees for the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS, RS and AA conceptualized the systematic review with input from BS, SK and VP. SS, RS, AA, and VP designed and implemented the search strategy. SS, RS, and AA screened, coded articles and extracted data with an assistance from PB, CM, BS and APK. SS and RS led write-up of results, with assistance from BS, AA, RS, CM, PB, APK, BKC and AQB. drafted the initial manuscript and interpreted the findings. VP, SK, BS, BKC and AQB assisted in revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Editorial Responsibility: Zaheer Babar, University of Huddersfield, UK.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shrestha, S., Shrestha, R., Ahmed, A. et al. Impact of pharmacist services on economic, clinical, and humanistic outcome (ECHO) of South Asian patients: a systematic review. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 15, 37 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-022-00431-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-022-00431-1