Abstract

Background

Drug dispensing is a clinical pharmacy service that promotes access to medicines and their rational use. However, there is a lack of evidence for the impact of drug dispensing on patients’ health outcomes. Thus, the purpose of this study was to assess the influence of drug dispensing on the clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes of patients attending community pharmacies.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in April 2021 using PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, LILACS, and Open Thesis. Two reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full-text articles according to the eligibility criteria. Methodological quality was assessed using tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute, and the literature was synthesized narratively.

Results

We retrieved 3,685 articles and included nine studies that presented 13 different outcomes. Regarding the design, they were cross-sectional (n = 4), randomized clinical trials (n = 4), and quasi-experimental (n = 1). A positive influence of drug dispensing on health outcomes was demonstrated through six clinical, four humanistic and three economic outcomes. Eight studies (88,9 %) used intermediate outcomes. The assessment of methodological quality was characterized by a lack of clarity and/or lack of information in primary studies.

Conclusions

Most articles included in this review reported a positive influence of drug dispensing performed by community pharmacists on patients’ health outcomes. The findings of this study may be of interest to patients, pharmacists, decision makers, and healthcare systems, since they may contribute to evidence-based decision-making, strengthening the contribution of community pharmacists to health care.

Trial registration

Registration: PROSPERO CRD42020191701.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, the irrational use of medicines is considered a major public health problem [1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than half of all medicines are prescribed, dispensed, or sold inappropriately and that around 50 % of patients fail to take them correctly [3]. This may have negative implications for patients and health systems, such as increased drug-related problems (DRP), hospital admissions due to adverse reactions, drug poisoning, antimicrobial resistance, and financial losses [4,5,6,7,8,9].

In this context, community pharmacists have a key role within the healthcare system for promoting rational use of medicines [10]. Tsuyuki and colleagues [11] noted that pharmacists see patients somewhere between 1.5 and 10 times more frequently than their primary care physicians. Thus, by providing clinical pharmacy services, community pharmacists can promote the rational use of medicines, closely monitor medication adherence, thereby improving pharmacotherapy and health outcomes of patients [12,13,14,15].

Among clinical pharmacy services, drug dispensing has high visibility in community pharmacies; it is accessible and serves a large number of patients seeking prescription drugs [16, 17]. Drug dispensing can be defined as a clinical pharmacy service that ensures the provision of medicines and other health products through the analysis of technical and legal aspects of prescription, assessment of individual health needs, and performance of interventions in the process of medicine use that includes pharmaceutical counseling and documentation of the interventions [18,19,20].

In recent years, studies have reported the impact of different clinical pharmacy services on the health outcomes of patients, such as medication review [21], medication reconciliation [22], medication synchronization [23], and medication therapy management [24, 25]. However, there is a lack of evidence for the impact of drug dispensing on health outcomes, and studies have mainly addressed certain aspects of this practice, such as the evaluation of the structure, process, and quality of the service [26,27,28,29,30]. Thus, high-quality studies are needed to evaluate the impact of drug dispensing on clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes of patients. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to assess the influence of drug dispensing on the health outcomes of patients who attended community pharmacies.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [31], Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [32] and Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) [33]. The systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD 42020191701).

Search strategy

PICO elements were used to address our clinical question, eligibility criteria, and search strategy. PICO represents an acronym for: (P) patient or problem, (I) intervention or exposure, (C) comparison intervention or exposure and (O) outcome of interest. In present study, PICO was as follows: (P) person, patients, or caregivers who received drug dispensing in community pharmacies; (I) drug dispensing performed by pharmacists; (C) not applicable; and (O) health outcomes influenced by dispensing.

A systematic search of the literature was performed in April 2021 using the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, LILACS, and Open Thesis. The search strategy used standard (MeSH terms) and non-standard terms related to “dispensing,” “pharmaceutical preparations,” “outcome assessment,” “health care,” “pharmacists,” “community pharmacy services,” and “pharmacies.” Each term was grouped through Boolean operators (AND and OR) to their synonyms and subcategories and adapted to each database. Additionally, we manually searched the reference lists of all eligible studies. The databases were searched for publications until April 2021. The complete search strategy is provided in Additional file 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (i) performed in community pharmacies; (ii) evaluated drug dispensing by pharmacists; (iii) evaluated the influence of drug dispensing on clinical, economic, and/or humanistic outcomes for patients’ health; and (iv) were published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. The following literature and studies were excluded: (i) conference abstracts; (ii) letters to the editor, (iii) literature reviews; (iv) systematic reviews or meta-analyses; v) studies not available in full, vi) results do not separate the intervention of the pharmacist from the intervention of other professionals, and vii) results do not separate dispensing from other services /interventions. Studies were not excluded on the basis of design, year of publication, or methodological quality.

Study selection

All duplicate studies were excluded. Next, two researchers (B.P. and L.G.R.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts, and subsequently, full texts were deemed relevant according to the eligibility criteria. The first two steps were performed using the Rayyan tool (http://rayyan.qcri.org) [34]. Any divergence in terms of study selection was judged by a third investigator (G.A.S.J.).

Analysis of the degree of agreement

Cohen’s kappa index (κ) was used to assess the level of agreement between the two reviewers in the article selection process, adopting a 95 % confidence interval. The agreement between reviewers was based on the following parameters: κ ≤ 0.10 without agreement; κ: 0.11–0.40 weak agreement; κ: 0.41–0.75 good agreement; and κ > 0.75 excellent agreement [35].

Data collection process

Two reviewers (B.P. and L.G.R.) independently extracted the data from the included articles using a pre-formatted Microsoft® Excel® spreadsheet. The following data were extracted: authors, year of publication, country, study design, number of participants, health outcomes, main results, and limitations or bias described. In the absence of data and/or clarity of the extracted variables, the authors of the included studies were contacted by email. Any divergence in the data extraction was resolved by reaching a consensus reached-through discussion. Articles that did not mention the study design in the methods were classified independently by two authors (G.A.S.J. and K.S.S.R.), and any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Definitions adopted in this systematic review

In this study, we considered that the process of dispensing involves technical and clinical components. The first one refers to the analysis of technical and legal aspects of prescription, correct selection of the prescribed medicine or health product to be dispensed, assembling and labeling, checking the accuracy of it and handing out to the patient. The second one involves the patient care process: (i) assessment of individual health needs of the patient, (ii) elaboration of the care plan with the performance of interventions in the process of medicine use that includes pharmaceutical counseling, and (iii) evaluation of the health outcomes of patients. This process should be documented and also involves frequent communication and collaboration with the patient and other health professionals [27, 36,37,38].

In this study, we adopted concepts that are widely used in studies on quality assessment in health care. We considered “health outcomes” as all measures attempting to describe the effects of care on the health status of patients and the population [39]. Thus, in view of the range of possible “health outcomes,” we refined the classification of “health outcomes” according to the Economic, Clinical, Humanistic Outcomes (ECHO) Model [40]. The ECHO model provides a theoretical framework for systematic planning of outcomes research according to the following classifications: economic outcomes (reduction in health care costs or utilization, such as hospitalizations, emergency department visits, clinic visits, and/or avoided drug costs), clinical outcomes (improved disease or symptom control, and use of health care treatment), and humanistic outcomes (measures of patient satisfaction and patients’ quality of life) [41,42,43,44].

We also classified “health outcomes” according to the following taxonomy: final endpoint (direct measure of an effect with a pharmaceutical product or service, e.g., mortality, morbidity, quality of life, patient satisfaction) and intermediate or surrogate endpoints (indirect measure of an effect in situations where a direct measure of effect is not feasible within a reasonable timeframe, e.g., HbA1c for patients with diabetes, and blood pressure for patients with hypertension) [39]. In literature, the terms “endpoint” and “outcome” are often used interchangeably [45]. Finally, in the present review, all definitions of terms and concepts related to “health outcomes” may be of interest to patients, pharmacists, decision makers, and healthcare systems.

Quality assessment

Three reviewers (B.P., L.G.R., and K.S.S.R.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The tools made available by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) were used: JBI’s critical appraisal tools for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (eight items) [46], JBI’s critical appraisal tools for Quasi-Experimental Studies (non-randomized experimental studies) (nine items) [47] and JBI’s critical appraisal tools for Randomized Controlled Trials (13 items) [48]. Each item was marked “yes,” if the article met the criteria of the item; “no,” if it did not meet the criteria; “unclear” if sufficient information to make a judgment was lacking; and “Not Applicable,” if the item did not apply to the article.

Results

Search and study selection

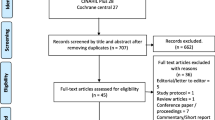

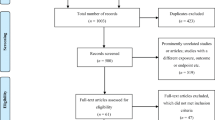

A total of 3,688 articles were identified from the initial search. After excluding duplicated or irrelevant articles based on titles and abstracts, 74 potentially relevant articles were retrieved for full-text evaluation. Out of these, nine met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process. There was strong agreement between the two evaluators in their analysis of titles and abstracts (κ1 = 0.892) and in their analysis of full studies (κ2 = 0.962). Articles that were excluded after full-text review and the reasons for exclusion are summarized in Additional file 2.

Flow diagram of literature search and screening process. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. All nine articles were published in English between 2006 and 2020. The studies were performed on four continents (America, Europe, Oceania, and Asia) and in seven different countries (Ireland, Brazil, Poland, the United Arab Emirates, Sweden, Australia, and the United States of America (USA). Most studies that were included were conducted in Australia (n = 3).

The articles reported the following design: cross-sectional (n = 4) [49, 52, 55, 56], randomized clinical trials (n = 4) [50, 51, 53, 54] and quasi-experimental (n = 1) [57]. The study sample was heterogeneous and varied in terms of number of patients (104–210) and community pharmacies (89–97). There was also heterogeneity in patient characteristics between studies, with the majority of them not specifying the patients’ characteristics or conditions (n = 5). The remaining four studies stated that patients used antibiotics (n = 1), antidepressants (n = 1) or inhaled drugs (n = 2).

Influence of drug dispensing on health outcomes

Thirteen different health outcomes were assessed in primary studies. Out of the four studies that evaluated clinical outcomes, two of them were related to the impact of dispensing on the care of patients with asthma [50, 54]. The more reported humanistic outcomes were satisfaction (n = 3) [51, 52, 57] and quality of life (n = 2) [50, 54]. Three economic outcomes were assessed in three studies, and the most frequent outcome was cost-saving (n = 3) [49, 55, 56]. Most studies evaluated intermediate endpoints [50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. In addition, health outcomes were measured heterogeneously in the included studies. Health outcomes, their classifications, and how they were measured are presented in Table 2.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the studies is presented in Additional file 3. Regarding cross-sectional studies, two of them (50 %) [49, 52] met at least five of the eight evaluated criteria. The quasi-experimental study met five of the nine evaluated criteria[57]. Only one randomized clinical trial met six of the thirteen criteria evaluated [54], and the remaining clinical trials met four or fewer criteria [50, 51, 53].

Discussion

The results of this systematic review demonstrate the positive influence of drug dispensing on the health outcomes of patients attending community pharmacies. Studies that address drug dispensing usually assess the quality of the practice showing a non-systematized and undocumented process [26, 30, 58]. Several strategies have been proposed to qualify this service, such as the development of instruments to support the practice and training pharmacists and pharmacy teams [27, 38, 59]. Another important point to be considered in quality assessment is knowing which health outcomes can be impacted by the services [39]. Thus, our results can help pharmacists to measure the influence of their practice on patients’ health. In addition, the results of this review can be used by policymakers and stakeholders to support public policies and other interventions that improve drug dispensing.

Regarding the influence of drug dispensing on clinical outcomes, most articles included intermediate endpoints. These findings may be related to the characteristics of drug dispensing as a fast service that supports many people, making it difficult to adopt designs that use the final endpoints [17, 60]. In addition, these results may reflect the purpose of drug dispensing in promoting access to medicines and their rational use. Thus, interventions by pharmacists are usually focused on improving the process of medication use by the patient [61, 62]. Besides, half of the studies that evaluated clinical outcomes were asthma related. The role of the pharmacist in the management of asthma is already well documented in the literature [63, 64]. Studies have shown that the most common pharmacists’ interventions on health outcomes in patients with asthma were patient counseling [65, 66]. Thus, since patient counseling is a core component of the drug dispensing, the service may contribute to the care of patients with asthma.

In relation to humanistic outcomes, studies have reported improved quality of life and patient satisfaction with drug dispensing service. Similarly, a randomized controlled trial performed in community pharmacies and cooperative general practices in the Netherlands showed that health-related quality of life in older patients increased (95 % CI: 0.94 to 5.8; p = 0.006) with use of a clinical medication review service [67]. In addition, systematic reviews have also revealed a high level of patient satisfaction with clinical pharmacy services in community pharmacies thus increasing customer loyalty [68, 69]. Analyzing these health outcomes is important for improving the quality of clinical pharmacy services [70]. Thereby, given the importance of humanistic outcomes for patient health, further studies are needed to assess the influence of drug dispensing on this outcome to expand and reinforce this evidence.

With respect to economic outcomes, few studies have evaluated the influence on reducing costs for patients and/or health systems. A systematic review that assessed the impact of interventions by community pharmacists on the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease reported similar results [71]. Although economic evaluation is challenging, in recent years, research in this field has expanded in the health sciences [72, 73]. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research has highlighted the importance of evaluating the economic outcomes of health services to reduce costs and improve decision-making regarding investments [74, 75]. Therefore, further studies are needed to assess the economic impact of clinical pharmacy services, including drug dispensing.

Regarding the assessment of methodological quality, a lack of clarity and/or an absence of information were identified in the studies included in this systematic review. These factors, coupled with a lack of consensus on the most appropriate tool to be used as well as the subjectivity of the evaluators in the use of these tools, can impact assessment of methodological quality [76, 77]. In addition, the research must be reported clearly so that readers can understand what was planned, how the research was carried out, and the results and conclusions, to enable data interpretation and reproducibility [78, 79]. Therefore, quality assessment tools to assist in methodological planning and reporting guidelines for the execution and reporting of the study are necessary.

This systematic review has several strengths and limitations. Meta-analysis could not be performed due to difficulties in combining the primary studies as they showed differences in populations and outcome measures. This makes it difficult to interpret our results and can impair the quality of the evidence generated. Furthermore, the quality assessment may have been influenced by the subjectivity of the researchers in the use of the quality assessment tools. We minimized this limitation by including three independent researchers. Thus, these limitations can be overcome by planning and carrying out future primary studies that are methodologically adequate and clearly reported. Conversely, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to identify health outcomes that are influenced by drug dispensing in community pharmacies. The findings of this review have the potential to be applied in clinical practice and can be used by researchers to guide studies of high scientific evidence evaluating the impact of drug dispensing and improving health outcomes, thus contributing to evidence-based decision-making. This strengthens efforts to promote rational use of medicines and to minimize the associated risks. In addition, we followed a rigorous methodological process: five different databases were searched using standardized and non-standardized terms; the references of the included studies were searched manually; and articles selection and data extraction were performed by two independent researchers, and a third was consulted in the event of a disagreement. Finally, articles were not excluded based on the methodological quality or study design.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides insight into the health outcomes that may be influenced by the drug dispensing provided by community pharmacists and revealed that most studies reported positive results. Most of the studied health outcomes were intermediate endpoints, with emphasis on clinical outcomes asthma related, cost savings, and satisfaction. A limited number of studies have assessed the influence of drug dispensing on health outcomes, addressing the need for further research in this field. Thus, policymakers and stakeholders may encourage public policies and develop interventions that encourage the qualification of drug dispensing in community pharmacies. We also observed heterogeneity in the tools used to measure health outcomes. We suggest that future studies, with high scientific evidence and methodological quality, should assess the outcomes influenced by drug dispensing identified in this review to strengthen the evidence for these services. Our results may also be useful for developing strategies to improve drug dispensing practice and, consequently, patients’ health outcomes to ensure rational medicine use and patient safety.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- DRP:

-

Drug-Related Problems

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- AMSTAR:

-

Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Review

- ECHO:

-

Economic, Clinical, Humanistic Outcomes

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- USA:

-

United States of America

- CAPES:

-

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil

- FAPES:

-

Foundation for Research Support of Espírito Santo

- SUS:

-

Brazilian Health System

References

Gyllensten H, Hakkarainen KM, Hagg S, Carlsten A, Petzold M, Rehnberg C, et al. Economic impact of adverse drug events – A retrospective population-based cohort study of 4970 adults. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–9.

Bouvy JC, Bruin ML, De, Koopmanschap MA. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in europe: A review of recent observational. Drug Saf. 2015;38:437–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0281-0.

World Health Organization. Promoting rational use of medicines: core components. WHO Policy Perspect Med. 2002;1–6. http://www.msh.org/. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

El Morabet N, Uitvlugt EB, van den Bemt BJF, van den Bemt PMLA, Janssen MJA, Karapinar-Çarkit F. Prevalence and preventability of drug-related hospital readmissions: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:602–8.

Mira JJ, Lorenzo S, Guilabert M, Navarro I, Pérez-Jover V. A systematic review of patient medication error on self-administering medication at home. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14:815–38.

Ayalew MB, Tegegn HG, Abdela OA. Drug related hospital admissions; a systematic review of the recent literatures. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2019;7:339–46.

Mao W, Vu H, Xie Z, Chen W, Tang S. Systematic review on irrational use of medicines in China and Vietnam. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–16.

Holloway K, Van Dijk L. The world medicines situation: rational use of medicines. World Med Situat. 2011;2:24–30.

Hitchen L. Adverse drug reactions result in 250,000 UK admissions a year. BMJ. 2006;332:1109.

Blalock SJ, Roberts AW, Lauffenburger JC, Thompson T, O’Connor SK. The effect of community pharmacy–based interventions on patient health outcomes: a systematic review. Med care Res Rev. 2013;70:235–66.

Tsuyuki RT, Beahm NP, Okada H, Al Hamarneh YN. Pharmacists as accessible primary health care providers: review of the evidence. Can Pharm J. 2018;151:4–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163517745517.

Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;10:608–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.006.

Dillon P, Mcdowell R, Smith SM, Gallagher P, Cousins G. Determinants of intentions to monitor antihypertensive medication adherence in Irish community pharmacy: a factorial survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20:131.

Suhaj A, Manu MK, Unnikrishnan MK, Vijayanarayana K, Rao CM. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacist intervention on health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder patients – a randomized controlled study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:78–83.

Laliberté M, Perreault S, Damestoy N, Lalonde L. Ideal and actual involvement of community pharmacists in health promotion and prevention: a cross-sectional study in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:192. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-192.

Angonesi D. Dispensação farmacêutica: uma análise de diferentes conceitos e modelos Pharmaceutical dispensing : an analysis of different concepts and models. Cien Saude Colet. 2008;13:629–40.

Martins SF, van Mil JWF, da Costa FA. The organizational framework of community pharmacies in Europe. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:896–905.

Ministério da saúde. Portaria No 3.916, de 30 de outubro de 1998. 1998. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/1998/prt3916_30_10_1998.html. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Hernández A, Garcia-Delgado P, Garcia-Cardenas V, Ocaña A, Labrador E, Orera ML, et al. Characterization of patients’ requests and pharmacists’ professional practice in oropharyngeal condition in Spain. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:300–9.

National Health Service. NHS Community Pharmacy services – a summary. 2013. http://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/CPCF-summary-July-2013.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Silva RDOS, Macêdo LA, Santos Júnior GA, Aguiar PM, Lyra Júnior DP. Pharmacist-participated medication review in different practice settings: Service or intervention? An overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–24.

Herledan C, Baudouin A, Larbre V, Gahbiche A, Dufay E, Alquier I, et al. Clinical and economic impact of medication non-adherence in drug-susceptible tuberculosis: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;24:1–13.

Nguyen E, Sobieraj DM. The impact of appointment-based medication synchronization on medication taking behaviour and health outcomes: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42:404–413.

Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, Blalock SJ, Coker-Schwimmer E, Posey R, et al. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:76–87.

Erku DA, Ayele AA, Mekuria AB, Belachew SA, Hailemeskel B, Tegegn HG. The impact of pharmacist-led medication therapy management on medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2017;15:1–7.

Cerqueira Santos S, Boaventura TC, Rocha KSS, de Oliveira Filho AD, Onozato T, de Lyra DP. Can we document the practice of dispensing? A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:634–44.

Rocha KSS, Cerqueira Santos S, Boaventura TC, dos Santos Júnior GA, de Araújo DCSA, Silvestre CC, et al. Development and content validation of an instrument to support pharmaceutical counselling for dispensing of prescribed medicines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;26:134–41.

Björnsdottir I, Granas AG, Bradley A, Norris P. A systematic review of the use of simulated patient methodology in pharmacy practice research from 2006 to 2016. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020;28:13–25.

Rickles NM, Huang AL, Gunther MB, Chan WJ. An opioid dispensing and misuse prevention algorithm for community pharmacy practice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15:959–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.02.004.

Puspitasari HP, Aslani P, Cert G, Krass I. A review of counseling practices on prescription medicines in community pharmacies. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2009;5:197–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.08.006.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:372.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:1–9.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley 1989.

Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: the patient-centered approach to medication management. 3rd ed. Ohio: Mcgraw-Hill; 2012.

Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Hughes C. Making the case for change: What researchers need to consider when designing behavior change interventions aimed at improving medication dispensing. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2015;12:149–53.

Cerqueira-Santos S, Rocha KSS, Boaventura TC, Jesus EMS, Silvestre CC, Alves BMCS, et al. Development and content validation of an instrument to document the dispensing of prescribed medicines. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44:430–9.

Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2003;15:523–30.

Kozma CM. Outcomes research and pharmacy practice. Am Pharm. 1995;NS35:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-3450(16)33891-0.

Farris KB, Kirking DM, Dalmady-Israel C, Rudis M. Assessing the quality of pharmaceutical care II. Application of concepts of quality assessment from medical care. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:215–23.

Singhal PK, Raisch DW, Gupchup G V. The impact of pharmaceutical services in community and ambulatory care settings: Evidence and recommendations for future research. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:1336–55.

Cheng Y, Raisch DW, Borrego ME, Gupchup GV. Economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes (ECHOs) of pharmaceutical care services for minority patients: a literature review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9:311–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.004.

Fujita K, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Quality indicators for responsible use of medicines: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020437.

European network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA). Endpoints used in relative effectiveness assessment: Clinical endpoints. 2015. https://eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/WP7-SG3-GL-clin_endpoints_amend2015.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Joanna Briggs Inst. 2017 https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/Appendix 7.5 Critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI GLOBAL WIKI. Accessed 15 July 2020.

Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). Joanna Briggs Inst. 2017. https://wiki.jbi.global/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=9273. Accessed 15 July 2020.

Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Joanna Briggs Inst. 2017. https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/Appendix+3.1 %3A+JBI+Critical+appraisal+checklist+for+randomized+controlled Accessed 15 July 2020.

Chong CP, March G, Clark A, Gilbert A, Hassali MA, Baidi M. A nationwide study on generic medicines substitution practices of Australian community pharmacists and patient acceptance. Health Policy (New York). 2011;99:139–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.002.

Basheti IA, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, Reddel HK. Evaluation of a novel educational strategy, including inhaler-based reminder labels, to improve asthma inhaler technique. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:26–33.

Crockett J, Taylor S, Grabham A, Stanford P. Patient outcomes following an intervention involving community pharmacists in the management of depression. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:263–9.

Ali HS, Aldahab AS, Mohamed EB, Prajapati SK, Badulla WFS, Alshakka M, et al. Patients ’ perspectives on services provided by community pharmacies in terms of patients ’ perception and satisfaction. J Young Pharm. 2019;11:279–84.

Merks P, Damian Ś, Balcerzak M, Drelich E, Białoszewska K, Cwalina N, et al. Patients’ perspective and usefulness of pictograms in short-term antibiotic therapy – Multicenter, randomized trial. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1667.

O’Dwyer SO, Greene G, Machale E, Cushen B, Sulaiman I, Boland F, et al. Personalized biofeedback on inhaler adherence and technique by community pharmacists: A cluster randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:635–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.008.

Westerlund T, Marklund B. Assessment of the clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacy interventions in drug-related problems. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:319–27.

Payne K, Unni EJ, Jolley B. Impact of dispensing services in an independent community pharmacy. Pharmacy. 2019;7:44.

Ferreira TXAM, Prudente LR, Dewulf NDLS, Provin MP, Cardoso TC, Da Silveira ÉA, et al. Impact of a drug dispensing model at a community pharmacy in Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil. Brazilian J Pharm Sci. 2018;54:1–10.

Wazaify M, Elayeh E, Tubeileh R, Hammad EA. Assessing insomnia management in community pharmacy setting in Jordan: A simulated patient approach. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–10.

Showande SJ, Orok EN. Impact of pharmacists’ training on oral anticoagulant counseling: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.018.

De Bie J, Kijlstra NB, Daemen BJG, Bouvy ML. The development of quality indicators for community pharmacy care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:666–71.

Iglésias-Ferreira, P, Santos HJ. Manual de dispensação farmacêutica Lisboa: Grupo de Investigação em Cuidados Farmacêuticos da Universidade Lusófona. 2009.

World Health Organization. Ensuring good dispensing practices. 2012. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19607en/s19607en.pdf. Accessed 09 Dec 2020.

Garcia-Cardenas V, Armour C, Benrimoj SI, Martinez-Martinez F, Rotta I, Fernandez-Llimos F. Pharmacists’ interventions on clinical asthma outcomes: A systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1134–43. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01497-2015.

Jia X, Zhou S, Luo D, Zhao X, Zhou Y, Cui Y. Effect of pharmacist-led interventions on medication adherence and inhalation technique in adult patients with asthma or COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:904–17.

Crespo-Gonzalez C, Fernandez-Llimos F, Rotta I, Correr CJ, Benrimoj SI, Garcia-Cardenas V. Characterization of pharmacists’ interventions in asthma management: A systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58:210–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2017.12.009.

Macedo LA, Silvestre CC, Alcântara T dos, de Magalhães Simões S, Lyra S. Effect of pharmacists’ interventions on health outcomes of children with asthma: A systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.01.002.

Verdoorn S, Kwint HF, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. Effects of a clinical medication review focused on personal goals, quality of life, and health problems in older persons with polypharmacy: A randomised controlled trial (DREAMER-study). PLoS Med. 2019;16:1–18.

Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. Feedback from community pharmacy users on the contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health: A systematic review of the peer reviewed and non-peer reviewed literature 1990–2002. Heal Expect. 2004;7:191–202.

Eades CE, Ferguson JS, O’Carroll RE. Public health in community pharmacy: A systematic review of pharmacist and consumer views. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:582.

Aziz MM, Wajid M, Yu F. A societal perception about community pharmacies in Pakistan: An outline of prospective investigation. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13:e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.078.

Hesso I, Gebara SN, Kayyali R. Impact of community pharmacists in COPD management: Inhalation technique and medication adherence. Respir Med. 2016;118:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.07.010.

Gammie T, Vogler S, Babar ZUD. Economic evaluation of hospital and community pharmacy services. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51:54–65.

Watts RD, Li IW. Use of checklists in reviews of health economic evaluations, 2010 to 2018. Value Heal. 2019;22:377–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.10.006.

Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia. Diretrizes metodológicas: diretriz de avaliação econômica. 2nd ed. Brasília, Brazil http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_metodologicas_diretriz_avaliacao_economica.pdf. Accessed 09 Dec 2020.

Postma MJ. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Conference. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2009;9:305–7.

Alves-Conceição V, Rocha KSS, Silva FVN, Silva ROS, Silva DT da, Lyra-Jr DP de. Medication regimen complexity measured by MRCI: A Systematic review to identify health outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:1117–34.

Ma LL, Wang YY, Yang ZH, Huang D, Weng H, Zeng XT. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil Med Res. 2020;7:1–11.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–8.

Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383:267–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the member of the Research Group on Implementation and Integration of Clinical Pharmacy Services in Brazilian Health System (SUS) for valuable discussions about pharmaceutical care.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001” and by Foundation for Research Support of Espírito Santo (FAPES). The funder had no role in in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KSSR, SCS, DPLJ and GASJ made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. BP, LGR, KSSR, GASJ made the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. BP, LGR and KSSR have drafted the work. KSSR, SCS, DPLJ and GASJ reviewed and provided important contributions to the structure and content of the manuscript. All authors accepted the final version of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Database search strategy.

Additional file 2.

List of excluded articles and reason for exclusion.

Additional file 3.

Assessment of methodological quality

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pizetta, B., Raggi, L.G., Rocha, K.S.S. et al. Does drug dispensing improve the health outcomes of patients attending community pharmacies? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 764 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06770-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06770-0