Abstract

The prevalence of asthma is about 9,7 % in women and 5,5 % in men.

Asthma can deteriorate during the perimenstrual period, a phenomenon known as perimenstrual asthma (PMA), which represents a unique, highly symptomatic asthma phenotype. It is distinguished from traditional allergic asthma by aspirin sensitivity, less atopy, and lower lung capacity.

PMA incidence is reported to vary between 19 and 40 % of asthmatic women. The presence of PMA has been related to increases in asthma-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations and emergency treatment including intubations.

It is hypothesized that hormonal status may influence asthma in women, focusing on the role of sex hormones, and specifically on the impact of estrogens’ fluctuations at ovulation and before periods.

This paper will focus on the pathophysiology of hormone triggered cycle related inflammatory/allergic events and their relation with asthma. We reviewed the scientific literature on Pubmed database for studies on PMA. Key word were PMA, mastcells, estrogens, inflammation, oral contraception, hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), and hormone free interval (HFI).

Special attention will be devoted to the possibility of reducing the perimenstrual worsening of asthma and associated symptoms by reducing estrogens fluctuations, with appropriate hormonal contraception and reduced HFI. This novel therapeutical approach will be finally discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and to 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the prevalence of asthma ranges from 9.1 to 9,7 % in adult women and 5.1 to 5,5 % in men, i.e. women present almost twice the risk men have [1, 2]. The increased vulnerability to inflammatory and autoimmune disease women experience after puberty is considered secondary to the different effect sex hormones have on the inflammatory defense system, and specifically on mast-cells (MC) [3, 4] and eosinophils cells. Fluctuations of estrogens trigger the mast-cell degranulation, whilst testosterone and other androgens are credited to have a stabilizing effect. Perimenstrual fluctuations of sex hormones in women are considered responsible for the specific worsening of many different perimenstrual symptoms and of specific inflammatory [5], autoimmune [6, 7] and pain related conditions, such as headache and pelvic pain [8–11].

The focus of this paper will be twofold: 1. To analyze the pathophysiology of menstrual cycle related events (ovulations and periods) and their relation with ovulatory and, with specific focus, PMA; 2. To discuss preventive strategies aiming at reducing the cycle – related inflammatory/allergic worsening of asthma and associated symptoms by reducing estrogens fluctuations, with appropriate hormonal contraception and reduced HFI.

Review

Asthma in women’s lifespan: windows of vulnerability

-

➢ Puberty: asthma is more common and severe in women during and after puberty. Prevalence is higher in women with early menarche [12]

-

➢ Ovulation: asthma exacerbations begin more often during the preovulatory (28 %) period in women with this chronic condition. Ovulation associated sex hormones’ fluctuations may trigger asthmatic crisis in vulnerable women [12–15].

-

➢ Menstruation: asthma can deteriorate during the perimenstrual period, a phenomenon known as perimenstrual asthma (PMA) which is usually much more severe and troublesome than the periovulatory worsening [16].

-

➢ Pregnancy: the clinical course of asthma during pregnancy is variable: it may worsen in about one-third of pregnant women, and may improve in about one-quarter [17–20]. It appears that mild asthma is likely to improve, whereas more severe forms of the disease frequently worsen [17–20]. Asthma generally improves during the last 4 weeks of gestation, and attacks are very infrequent during labor and delivery [17, 20]

-

➢ Puerperium: changes in the asthmatic state during pregnancy generally last up to 3 months after delivery [17, 20].

-

➢ Menopause: postmenopausal women present a significantly lower risk of developing asthma than premenopausal women of similar age [17, 21]

-

➢ HRT: results in the effect of HRT on asthma are controversial. In one study, ever using HRT was associated with increased risk of hospital admission for asthma. This risk was highest with the longest duration of HRT use. The risk was significantly increased for all types of HRT regimens [22]

In other studies neither the discontinuation nor reinitiation of HRT in the postmenopausal period has any effect on airway obstruction in asthmatic women [21, 23].

Definition of PMA

A clear definition of PMA does not exist in the literature. Murpyh et al. investigated the following types of PMA definitions: self-reported PMA, increased symptoms, increased medication use, decreased peak flow or a combination of changes in symptoms, medication and peak flow. The variability of the definition of PMA affects the recollection of the data in the different studies and affects the prevalence in different populations [24].

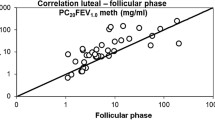

Generally, the deterioration of asthma during the luteal phase and/or during the first days of menstruation, is characterized by deterioration of lung function tests [25].

PMA represents a unique, highly symptomatic, and exacerbation-prone asthma phenotype associated with aspirin sensitivity, less atopy (less IgE level), and lower forced vital capacity, that distinguish it from traditional allergic asthma [26].

Prevalence of PMA

PMA incidence is reported to be as high as 40 % of asthmatic women [27].

In population based studies, rates of admissions to hospital for asthma are similar by sex in the early teenage years [13, 28, 29] but three times higher in women than in men aged 20–50 years. After menopause the incidence of asthma falls and equalizes again with men [13, 28, 29].

The presence of PMA has been related to increases in asthma-related Emergency Department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, intubations, and near-fatal and fatal events [13, 26].

ED visits occur more commonly among women in the preovulatory (28 %) and perimenstrual (27 %) phases (p = 0.004) [13].

These findings, together with the growing body of evidence for sex differences in asthma [12, 13], support the hypothesis that hormonal status may influence asthma in women, focusing on the role of sex hormones, and specifically on the impact of estrogens’ fluctuations at ovulation and before periods [13].

Why do ovulation and menstruation trigger asthma attacks?

New data suggest that specific pathophysiologic mechanisms could be responsible for PMA attacks. An updated physiology of the cycle related events will be briefly reviewed here, to set the scenario which leads to PMA. It focuses on the inflammatory nature of the menstrual process, currently understood as the “genital sign of systemic endocrine and inflammatory events” [3, 4].

-

➢ The updated physiology of estrogen’ fluctuations at ovulation and menstruation

The physiology of the menstrual cycle is characterized by fluctuating levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone. The perimenstrual phase is characterized by a decline in progesterone and oestradiol levels [30], which triggers MC degranulation at the basal layer of the endometrium. This induces a local (with endometrial tissue breakdown and menstruation) and a systemic inflammation (with MC and eosinophil degranulation and consequent increase in inflammatory markers in tissues where hyperactive MC are already present, such as the lung/bronchial tissues of an asthmatic woman) [3].

-

➢ Effect of estrogens on immune cells

Sex hormones are effective modulators of immune and inflammatory responses [31]. Estrogens significantly influence the incidence and/or the course of several autoimmune diseases, as well as bacterial and parasitic infectious processes [31–34]. They exert their actions through the estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha and -beta [31, 34–36], which are expressed by several immune cells [37].

-

Eosinophils : Chronic administration of E2 to ovariectomized mice prevents eosinophilia in sterile peritonitis induced by thyoclicolate challenge (with a sixfold decrease in circulating eosinophils as compared with untreated ovariectomized mice) [31].

-

MC: MC are considered to be the chief protagonists in the clinical scenario of inflammation and pain [3, 4, 38–40]. MC are present in the endometrium and myometrium and are predominantly localized to the basal layer [41]. MC are upregulated in response to a wide range of stimuli, including neurogenic factors, fluctuating oestrogen levels and menstrual blood in the tissue [9]. Once activated, MC degranulate and release a range of inflammatory mediators which perpetuate the immune response [9]. Sex hormones regulate MC functionality and distribution in several tissues [42–47], both in physiological and pathological conditions. In this regard, a relationship between female sex hormones, MC and development of asthma and allergy has been suggested [46–49]. Furthermore, the presence of sex steroid receptors on MC indicates that sex hormones may exert their biological effects by binding to these receptors [49].

Asthma and respiratory atopy

Asthma, allergies and other manifestations of atopy have also been shown to fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle [50].

The female immune response changes throughout the menstrual cycle. Many studies support this theory:

-

➢ One study examining skin prick testing in women with aero-allergens reported significantly increased wheel-and- flare responses on days 12–16 of the menstrual cycle which correspond to ovulatory peak estrogen levels [51].

-

➢ The menstrual phase has also been shown to influence nasal reactivity, as the period of peak estrogen is correlated with the nasal mucosa becoming hyperreactive to histamine [52].

-

➢ Bronchial hyperreactivity is more likely in the perimenstrual period than at other points in the cycle; PMA seems to be closely linked to total IgE levels but not to specific allergens [53].

-

➢ Atopic asthma, a specific asthma phenotype, is often associated to an irregular menstrual cycle [54, 55]

Asthma and combined contraceptive pill

Studies have demonstrated a role for both exogenous estrogen and progesterone in the management of PMA [25, 56–58]. In a prospective study on postpubertal women with asthma, the 106 women using oral contraception (OC) had reduced asthma symptoms, improved pulmonary function, and improved asthma control compared with those not using OC [57].

A study from Tan et al. compared airway reactivity to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) in female asthmatics with natural menstrual cycles and those taking the OC (with 21 days of active treatment followed by a seven-day break). There was a significant increase in airway reactivity in the group with natural menstrual cycles in the luteal phase, coincident with the increase in progesterone and estradiol. In the OC group the hormonal profile was stable, and so was bronchial reactivity. They concluded that asthmatic patients receiving the OC had attenuated cyclical change in airway reactivity as well as reduced diurnal peak expiratory flow rate variability, which was associated with suppression of the normal luteal phase rise in sex-hormones [58].

How and why can OC reduce PMA

How this beneficial effect is obtained? One possible explanation could be the regulation of the immune system. An exaggerated Th2-driven response is believed to lead the inflammatory allergic reaction of asthma. Particularly, Th2 cytokines induce the production of IgE and mast cells, activation and recruitment of eosinophils, and airway hyperreactivity and mucus secretion [59]. Of major importance are induced regulatory T cells (iTregs), which can inhibit or suppress the effector function of T helper cells and their tolerance to environmental allergens [59–61] thus preventing the induction or reducing the severity of asthma [59–61].

Sex hormones may directly contribute to the perturbed development of iTregs perpetuating the asthmatic inflammation in an at-risk female population. Consistent with this possibility, the lower and more stable levels of circulating hormones in women with asthma using OC were associated with higher percentages of iTregs when compared with non-OC patients [59–61].

These results identify an impact of sex hormones in the capacity of T cells to polarize towards a regulatory phenotype and suggest the regulation of peripheral T cell lineage plasticity as a potential mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of OC in women with asthma [59–61].

Preventive strategies for PMA

Understanding that the menstrual fall of estradiol and progesterone triggers asthmatic crises in vulnerable women may suggest new preventive strategies which are pathophysiologically oriented, such as stabilizing estradiol and progesterone/progestins levels and reducing the hormone free interval (HFI), when OC is considered. Prospective controlled studies are needed to test this working hypothesis.

Menstrual symptoms are complained of as well, although with reduced intensity, during the HFI. The original interval of seven days has been progressively reduced to 4 and to 2, with a significant reduction of menstrual symptoms, or deleted for three or more months (“extended regimens”, when the woman may have periods every 91 days). A solid evidence (Harmony I and II) [62, 63] supports the significant advantages in terms of menstrual headache and chronic pelvic pain improvement by reducing HFI.

Advantages of providing stable hormone levels in place of monthly hormonal fluctuations

Menstrual bleeding is not biologically necessary in women taking OC. Rather, for physical and mental good health, women require appropriate, stable levels of oestrogens, progesterone and androgens [3, 4].

OC have traditionally been administered with 21 days of active treatment followed by a seven-day break (a ‘21/7’ pattern) during which withdrawal bleeding occurs. It is worth noting that the 7 days HFI, designed in the pioneering years of OC, had a psychosocial, not a medical reason. It was simply needed to reassure women that they were not pregnant, amenorrhea being for millennia the first symptom and sign of pregnancy. Today this is no more the case. Data [64] show a strong cultural effect: women in high income country tend to have a very flexible relationship with their periods, the Netherland leading the ranking with 85 % asking to postpone/avoid the cycle, vs 10 % of women in Turkey. Newer formulations are available in which the HFI is reduced or in some cases eliminated altogether.

There are three major rationales for a shorter HFI:

-

1.

To reduce menstrual symptoms

Shortening HFI reduces genital and systemic inflammation and symptoms associated with hormone withdrawal. In a study of nearly 300 women, pelvic pain, headache, breast tenderness, bloating/swelling and analgesic use were all significantly more frequent during the seven-day HFI than in the 21 days of active treatment [65]. OC with a shortened HFI provides markedly greater suppression of ovarian activity and limits the extent of exogenous hormonal fluctuations throughout the cycle, and has been shown to reduce or eliminate these symptoms [65].

-

2.

To provide more powerful ovarian suppression and consequently increase contraceptive efficacy [65].

-

3.

To reduce heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB)

HMB affects around one in three women and has a significant negative impact on quality of life [66, 67]. The pill with oestradiol valerate and dienogest (E2V/DNG), administered on a 26/2 regimen, significantly reduces the duration and severity of the menstrual bleeding and it is the only one approved for the treatment of HMB and consequent anemia.

Anemia is a risk factor for asthma

In one study from Ramakrishnan et al., anemic children resulted 5.75 times more susceptible to asthmatic attacks when compared with non-anemic children [68].

Moreover, anemia can worsen dyspnea related to asthma, severely impairing oxygen delivery because the bulk of oxygen carried in the blood is hemoglobin-bound [69].

An adequate level of iron has a protective effect on the respiratory system. A study from Hale et al., proved that mice fed an iron-supplemented diet had markedly decreased allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity, eosinophil infiltration, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, compared with control mice on an unsupplemented diet that generated mild iron deficiency but not anemia. In vitro, iron supplementation decreased MC granule content, IgE-triggered degranulation, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines post-degranulation. Iron supplementation can decrease the severity of allergic inflammation in the lung, via multiple mechanisms that affect MC activity [70].

Evidence supporting the benefits of reducing the HFI

From 7 to 4 days

Shortening of the 7-day HFI (21/7) from 7 to 4 days (24/4): all of the 24/4 regimens, including EE/DSPR, EE/Noretindrone acetate and E2/NOMAC, have shown comparable or more favourable effects than 21/7 regimens in terms of efficacy and safety profiles.

This translates into improved menstrual symptoms control: significant reduction of PMS symptoms [71], dysmenorrhoea [71], premenstrual dysphoria disorder (PMDD) [72], and improvements in quality of life [4].

From 7 to 2 days

The benefits of shortening the HFI may be even greater when further reducing it from 7 to 2 days. E2V/DNG is a 26/2-pattern COC that features quadriphasic dosing, delivering a reducing dose of oestrogen over days 1–26 and an increasing dose of progestogen over days 3–24, followed by two hormone-free days. E2V/DNG is the first OC approved for the treatment of HMB due to endometrial dysfunction. Benefits include:

-

➢ Contraceptive efficacy [73]

-

➢ Reduction of HMB, thus reducing anemia that potentiate asthma with an independent mechanism [68–70, 74, 75].

Role of the E2V/DNG pill in reducing menstrual symptoms

E2V/DNG reduces the intensity of menstrual symptoms by offering constant levels of oestradiol around 50 picograms/mL (range 37–62), thus modulating and reducing the MC degranulation triggered by a more dramatic hormonal fall typical of the natural cycle (when oestradiol moves from 50 to 100 pg/mL after periods, up to 400–500 pg/mL at ovulation and around 200 pg/mL in the luteal phase) [4].

Depression associated with HMB

Reducing the blood loss, E2V/DNG decreases iron-loss anemia, which may be a risk factor for anxiety [76, 77], poor concentration, attention and memory [78], fatigue [79].

The effect of E2V/DNG on maintaining iron levels has a positive effect on the dopaminergic system, which is involved in ameliorating mood, assertiveness, physical and mental energy, and reducing the risk of depression. Moreover, it can reduce the periodical asthmatic crisis, which may be so important to cause a post-traumatic stress disorder [80], and the need of corticosteroids boluses and chronic therapy thus reducing the collateral effects such as weight augmentation [81]

Menstrual migraine and pelvic pain

E2V/DNG has shown a reduction in systemic symptoms associated with the HFI such as headache [82].

Conclusions

Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases. The prevalence of asthma ranges from 9.1 to 9,7 % in adult women and 5.1 to 5,5 % in men [1, 2].

PMA is usually described as cyclical deterioration of asthma during the luteal phase and/or during the first days of menstruation [25, 26], and is reported to be about 19 % of asthmatic women, while other studies reported the incidence to be as high as 40 % [27].

These menstrual phase findings support the hypothesis that hormonal status may influence asthma in women, focusing on the role of sex hormones, and specifically on the impact of estrogens’ fluctuations at ovulation and before periods [28].

Women today have many more periods in their lifetime than their ancestors. Menstrual bleeding is not biologically necessary in women taking hormonal contraceptives. Furthermore, it may be advantageous for the women to have more stable levels of hormones throughout the cycle. The monthly fluctuations in oestrogens, progesterone and androgens are associated with a range of symptoms, both genital (i.e. vaginal bleeding, heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhoea and pelvic pain) and systemic (depression, fatigue, headache, IBS symptoms, asthma and allergy), triggered by a local and systemic rise in inflammatory molecules released by MC when estrogens drop. These symptoms arise through a complex interaction between the endocrine and immune systems.

OCs traditionally feature a 7-day HFI, during which menstruation occurs. Formulations with a shorter HFI have recently been developed with the aim of offering a reduction in hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms together with more powerful ovarian suppression. E2V/DNG is administered on a 26/2 regimen and has been shown to offer high contraceptive efficacy together with a reduction in heavy menstrual bleeding, improvement in hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms and improvement in sexual function. E2V/DNG may, therefore, be a good alternative to conventional 21/7 COCs for women with bothersome COC- or menstruation-related symptoms, as exacerbation of asthma crisis.

Prospective controlled studies are needed to confirm the working hypothesis, supported by preliminary evidence, that reduction of HFI translates into a significant reduction of PMA; to evaluate in head to head studies if a regimen with natural estradiol-valerate/dienogest with 2 days interval has a different impact on PMA in comparison to a continuous regimen with EE 30 mcg and levonorgestrel.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: asthma prevalence, disease characteristics, and self-management education: United States, 2001--2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:547–52.

Kim S, Camargo Jr CA. Sex-race differences in the relationship between obesity and asthma: the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2000. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:666–73.

Graziottin A, Zanello PP. Menstruation, inflammation and comorbidities: implications for women’s health. Minerva Ginecol. 2015;67:21–34.

Graziottin A. The shorter, the better: A review of the evidence for a shorter contraceptive hormone-free interval. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;21(2):1–13.

Heitkemper MM, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Hertig V, Bond EF. Symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:420–30.

Rubtsova K, Marrack P, Rubtsov AV. Sexual dimorphism in autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2187–93.

Zandman-Goddard G, Peeva E, Shoenfeld Y. Gender and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:366–72.

Graziottin A, Skaper SD, Fusco M. Inflammation and Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Biological Trigger for Depression in women? J Depress Anxiety. 2013;3:142–50.

Graziottin A, Skaper SD, Fusco M. Mast cells in chronic inflammation, pelvic pain and depression in women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30:472–7.

Martin VT, Lipton RB. Epidemiology and biology of menstrual migraine. Headache. 2008;48 Suppl 3:S124–30.

Hassan S, Muere A, Einstein G. Ovarian hormones and chronic pain: A comprehensive review. Pain. 2014;155:2448–60.

Zein JG, Erzurum SC. Asthma is Different in Women. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:28.

Brenner BE, Holmes TM, Mazal B, Camargo Jr CA. Relation between phase of the menstrual cycle and asthma presentations in the emergency department. Thorax. 2005;60:806–9.

Pereira Vega A, Sánchez Ramos JL, Maldonado Pérez JA, Alvarez Gutierrez FJ, Ignacio García JM, Vázquez Oliva R, et al. Variability in the prevalence of premenstrual asthma. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:980–6.

Macsali F, Svanes C, Sothern RB, Benediktsdottir B, Bjørge L, Dratva J, et al. Menstrual cycle and respiratory symptoms in a general Nordic-Baltic population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:366–73.

Skoczyński S, Semik-Orzech A, Szanecki W, Majewski M, Kołodziejczyk K, Sozańska E, et al. Perimenstrual asthma as a gynecological and pulmonological clinical problem. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2014;23:665–8.

Balzano G, Fuschillo S, Melillo G, Bonini S. Asthma and sex hormones. Allergy. 2001;56:13–20.

Gluck JC, Gluck P. The effects of pregnancy on asthma: a prospective study. Ann Allergy. 1976;37:164–8.

Schatz M. Asthma and pregnancy. J Asthma. 1990;27:335–9.

Schatz M, Harden K, Forsythe A, Chilingar L, Hoffman C, Sperling W, et al. The course of asthma during pregnancy, post partum, and with successive pregnancies: a prospective analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;81:509–17.

Troisi RJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Trichopoulos D, Rosner B. Menopause, postmenopausal estrogen preparations, and the risk of adult-onset asthma. A prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1183–8.

Bønnelykke K, Raaschou Nielsen O, Tjønneland A, Ulrik CS, Bisgaard H, Andersen ZJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and asthma-related hospital admission. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:813–6. e5.

Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Morris MJ. The effects of estrogen replacement therapy on airway function in postmenopausal, asthmatic women. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2717–20.

Murphy VE1, Gibson PG. Premenstrual asthma: prevalence, cycle-to-cycle variability and relationship to oral contraceptive use and menstrual symptoms. J Asthma. 2008;45:696–704.

Dratva J, Schindler C, Curjuric I, Stolz D, Macsali F, Gomez FR, SAPALDIA Team. Perimenstrual increase in bronchial hyperreactivity in premenopausal women: results from the population-based SAPALDIA 2 cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:823–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.938.

Rao CK, Moore CG, Bleecker E, Busse WW, Calhoun W, Castro M, et al. Characteristics of Perimenstrual Asthma and Its Relation to Asthma Severity and Control: : data from the Severe Asthma Research Program. Chest. 2013;143:984–92. doi:10.1378/chest.12-0973.

Gibbs CJ, Coutts II, Lock R, Finnegan OC, White RJ. Premenstrual exacerbation of asthma. Thorax. 1984;39:833–6.

Skobeloff EM1, Spivey WH, St Clair SS, Schoffstall JM. The influence of age and sex on asthma admissions. JAMA. 1992;268:3437–40.

Becklake MR, Kauffmann F. Gender difference in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax. 1999;54:1119–38.

Owen Jr JA. Physiology of the menstrual cycle. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:333–8.

Douin Echinard V, Calippe B, Billon Galès A, Fontaine C, Lenfant F, Trémollières F, et al. Estradiol administration controls eosinophilia through estrogen receptor-alpha activation during acute peritoneal inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:145–54. doi:10.1189/jlb.0210073.

Michael E, Bundy DA, Grenfell BT. Re-assessing the global prevalence and distribution of lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol. 1996;112:409–28.

Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:777–80.

Huygen K, Palfliet K. Strain variation in interferon alpha production of BCG-sensitized mice challenged with PPD II. Importance of one major autosomal locus and additional sexual influences. Cell Immunol. 1984;85:75–81.

Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9.

Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 1995;83:851–7.

Phiel KL, Henderson RA, Adelman SJ, Elloso MM. Differential estrogen receptor gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell populations. Immunol Lett. 2005;97:107–13.

Berbic M, Fraser IS. Immunology of normal and abnormal menstruation. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2013;9:387–95.

Berbic M, Ng CH, Fraser IS. Inflammation and endometrial bleeding. Climacteric. 2014;23:1–7.

Lockwood CJ. Mechanisms of normal and abnormal endometrial bleeding. Menopause. 2011;18:408–11.

Menzies FM, Shepherd MC, Nibbs RJ, Nelson SM. The role of mast cells and their mediators in reproduction, pregnancy and labour. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:383–96.

Muñoz-Cruz S, Mendoza-Rodríguez Y, Nava-Castro KE, Yepez-Mulia L, Morales-Montor J. Gender-Related Effects of Sex Steroids on Histamine Release and FcεRI Expression in Rat Peritoneal Mast Cells. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:351829. doi:10.1155/2015/351829.

Padilla L, Reinicke K, Montesino H, Villena F, Asencio H, Cruz M, et al. Histamine content and mast cells distribution in mouse uterus: the effect of sexual hormones, gestation and labor. Cell Mol Biol. 1990;36:93–100.

Vliagoftis H, Dimitriadou V, Boucher W, Rozniecki JJ, Correia I, Raam S, et al. Estradiol augments while tamoxifen inhibits rat mast cell secretion. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;98:398–409.

Vliagoftis H, Dimitriadou V, Theoharides TC. Progesterone triggers selective mast cell secretion of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;93:113–9.

Kim MS1, Chae HJ, Shin TY, Kim HM, Kim HR. Estrogen regulates cytokine release in human mast cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2001;23:495–504.

Vasiadi M, Kempuraj D, Boucher W, Kalogeromitros D, Theoharides TC. Progesterone inhibits mast cell secretion. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006;19:787–94.

Osman M. Therapeutic implications of sex differences in asthma and atopy. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:587–90.

Zhao XJ, McKerr G, Dong Z, Higgins CA, Carson J, Yang ZQ, et al. Expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors by mast cells alone, but not lymphocytes, macrophages or other immune cells in human upper airways. Thorax. 2001;56:205–11.

Muñoz-Cruz S, Togno-Pierce C, Morales-Montor J. Non-reproductive effects of sex steroids: their immunoregulatory role. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:1714–27.

Kalogeromitros D, Katsarou A, Armenaka M, Rigopoulos D, Zapanti M, Stratigos I. Influence of the menstrual cycle on skin-prick test reactions to histamine, morphine and allergen. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25:461–6.

Haeggström A, Ostberg B, Stjerna P, Graf P, Hallén H. Nasal mucosal swelling and reactivity during a menstrual cycle. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2000;62:39–42.

Pereira-Vega A, Sánchez JL, Maldonado JA, Borrero F. Premenstrual asthma and atopy markers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:218–22.

Galobardes B, Patel S, Henderson J, Jeffreys M, Smith GD. The association between irregular menstruations and acne with asthma and atopy phenotypes. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:733–7.

Svanes C, Real FG, Gislason T, Jansson C, Jögi R, Norrman E, et al. Association of asthma and hay fever with irregular menstruation. Thorax. 2005;60:445–50.

Chandler MH, Schuldheisz S, Phillips BA, Muse KN. Premenstrual asthma: the effect of estrogen on symptoms, pulmonary function, and beta 2-receptors. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17(2):224–34.

Salam MT, Wenten M, Gilliland FD. Endogenous and exogenous sex steroid hormones and asthma and wheeze in young women. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1001–7.

Tan KS, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Modulation of airway reactivity and peak flow variability in asthmatics receiving the oral contraceptive pill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1273–7.

Vélez Ortega AC, Temprano J, Reneer MC, Ellis GI, McCool A, Gardner T, et al. Enhanced generation of suppressor T cells in patients with asthma taking oral contraceptives. J Asthma. 2013;50:223–30.

Holgate ST, Polosa R. Treatment strategies for allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:218–30.

Ray A, Khare A, Krishnamoorthy N, Qi Z, Ray P. Regulatory T cells in many flavors control asthma. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:216–29.

Jensen JT, Parke S, Mellinger U, Serrani M, Mabey Jr RG. Hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms: comparison of oestradiol valerate/dienogest versus ethinylestradiol/norgestimate. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:274–83.

Macìas G1, Merki Feld GS, Parke S, Mellinger U, Serrani M. Effects of a combined oral contraceptive containing oestradiol valerate/dienogest on hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms: results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled HARMONY II study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:591–6.

Szarewski A, Von Stenglin A, Rybowski S. Women’s attitudes towards monthly bleeding: results of a global population-based survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2012;17:270–83. doi:10.3109/13625187.2012.684811.

Bitzer J, Banal-Silao MJ, Ahrendt HJ, Restrepo J, Hardtke M, Wissinger-Graefenhahn U, et al. Hormone withdrawal-associated symptoms with ethinylestradiol 20 μg/drospirenone 3 mg (24/4 regimen) versus ethinylestradiol 20 μg/desogestrel 150 μg (21/7 regimen). Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:501–9. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S77942.

Peuranpaa P, Helioovara-Peippo S, Fraser I, Paavonen J, Hurskainen R. Effects of anemia and iron deficiency on quality of life in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:654–60.

Karlsson TS, Marions LB, Edlund MG. Heavy menstrual bleeding significantly affects quality of life. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:52–7.

Ramakrishnan K, Borade A. Anemia as a risk factor for childhood asthma. Lung India. 2010;27:51–3. doi:10.4103/0970-2113.63605.

Clark AL, Piepoli M, Coats AJ. Skeletal muscle and the control of ventilation on exercise: evidence for metabolic receptors. Eur J Clin Invest. 1995;25:299.

Hale LP, Kant EP, Greer PK, Foster WM. Iron supplementation decreases severity of allergic inflammation in murine lung. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45667.

Micks EA, Jensen JT. Treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with the estradiol valerate and dienogest oral contraceptive pill. Adv Ther. 2013;30:1–13.

Graham CA, Ramos R, Bancroft J, Maglaya C, Farley TM. The effects of steroidal contraceptives on the well-being and sexuality of women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-centre study of combined and progestogen-only methods. Contraception. 1995;52:363–9.

Willis SA, Kuehl TJ, Spiekerman AM, Sulak PJ. Greater inhibition of the pituitary--ovarian axis in oral contraceptive regimens with a shortened hormone-free interval. Contraception. 2006;74:100–3.

Fraser IS, Römer T, Parke S, Zeun S, Mellinger U, Machlitt A, et al. Effective treatment of heavy and/or prolonged menstrual bleeding with an oral contraceptive containing estradiol valerate and dienogest: a randomized, double-blind Phase III trial. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2698–708.

Jensen JT, Parke S, Mellinger U, Machlitt A, Fraser IS. Effective treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with estradiol valerate and dienogest: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:777–87.

Gulmez H, Akin Y, Savas M, Gulum M, Ciftci H, Yalcinkaya S, et al. Impact of iron supplementation on sexual dysfunction of women with iron deficiency anemia in short term: a preliminary study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1042–6.

Unger EL, Wiesinger JA, Hao L, Beard JL. Dopamine D2 receptor expression is altered by changes in cellular iron levels in PC12 cells and rat brain tissue. J Nutr. 2008;138:2487–94.

Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron treatment normalizes cognitive functioning in young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:778–87.

Wang W, Bourgeois T, Klima J, Berlan ED, Fischer AN, O’Brien SH. Iron deficiency and fatigue in adolescent females with heavy menstrual bleeding. Haemophilia. 2013;19:225–30.

Chung MC, Wall N. Alexithymia and posttraumatic stress disorder following asthma attack. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84:287–302.

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J, Bijlsma JW, Freeman A, George V, et al. Population-based assessment of adverse events associated with long-term glucocorticoid use. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:420.

Nappi RE, Terreno E, Sances G, Martini E, Tonani S, Santamaria V, et al. Effect of a contraceptive pill containing estradiol valerate and dienogest (E2V/DNG) in women with menstrually-related migraine (MRM). Contraception. 2013;88:369–75.

Authors’ contributions

AG conceived this clinical perspective, its design and cohordination and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, the content of which has been presented to national and international congresses. AS helped to write the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

AG is currently a member of the Speakers’ bureau for Abbott, Bayer HealthCare, Deakos, Fidia, Loli-Pharm, Menarini, Shionogi and Zambon. In 2014–2015 she participated in scientific advisory boards for Bayer HealthCare, Fidia and Menarini and worked as consultant for Alfa Wassermann, Bayer HealthCare, Deakos, Epitech, Fidia, Lolipharm, Menarini, Shionogi and Zambon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Graziottin, A., Serafini, A. Perimenstrual asthma: from pathophysiology to treatment strategies. Multidiscip Respir Med 11, 30 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-016-0065-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-016-0065-0