Abstract

Background

There is substantial variation in the practice of preoperative medical evaluation (PME) and limited evidence for its benefit, which raises concerns about overuse. Surgeons have a unique role in this multidisciplinary practice. The objective of this qualitative study was to explore surgeons’ practices and their beliefs about PME.

Methods

We conducted of semi-structured interviews with 18 surgeons in Baltimore, Maryland. Surgeons were purposively sampled to maximize diversity in terms of practice type (academic vs. private practice), surgical specialty, gender, and experience level. General topics included surgeons’ current PME practices, perceived benefits and harms of PME, the surgical risk assessment, and potential improvements and barriers to change. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis to identify themes, which are presented as assertions. Transcripts were re-analyzed to identify supporting and opposing instances of each assertion.

Results

A total of 15 themes emerged. There was wide variation in surgeons’ described PME practices. Surgeons believed that PME improves surgical outcomes, but not all patients benefit. Surgeons were cognizant of the financial cost of the current system and the potential inconvenience that additional tests and office visits pose to patients. Surgeons believed that PME has minimal to no risk and that a normal PME is reassuring to them and patients. Surgeons were confident in their ability to assess surgical risk, and risk assessment by non-surgeons rarely affected their surgical decision-making. Hospital and anesthesiology requirements were a major driver of surgeons’ PME practices. Surgeons did not receive much training on PME but perceived their practices to be similar to their colleagues. Surgeons believed that PME provides malpractice protection, welcomed standardization, and perceived there to be inadequate evidence to significantly change their current practice.

Conclusions

Views of surgeons should be considered in future research on and reforms to the PME process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients often undergo extensive, multidisciplinary evaluation prior to elective surgery. Initially, the evaluation is aimed at determining whether patients indeed have a surgical condition. Once this has been determined and a tentative decision to proceed with surgery has been made, patients often undergo additional preoperative medical evaluation (PME)—testing and evaluation aimed at assessing and minimizing surgical risk (Riggs and Segal 2016). There is substantial variation in this practice of PME (Thilen et al. 2013; van Gelder et al. 2012; Wijeysundera et al. 2012) and limited evidence for benefit (Balk et al. 2014; Wijeysundera et al. 2010), which has raised concerns about overuse (Baxi and Lakin 2015; Brateanu and Rothberg 2015; Smetana 2015).

The perioperative process is complex and includes diverse provider types, including surgeons, anesthesiologists, primary care and medical specialists, and spans multiple settings, including the outpatient clinic, operating room, and hospital. Surgeons are uniquely situated as they follow patients through the entirety of this process, from prior to surgery to the hospital to the postoperative follow-up. This unique vantage point may give surgeons important insights regarding the processes of PME that can assist with improving the efficiency of the system. However, knowledge of surgeons’ views on PME is limited. Several recent qualitative studies focused narrowly on preoperative testing in low-risk situations (Brown and Brown 2011; Patey et al. 2012), and several quantitative surveys focused on preoperative consultations (Katz et al. 1998; Pausjenssen et al. 2008). The objective of this study was to more broadly explore surgeons’ modern practices and beliefs about PME.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a qualitative study consisting of semi-structured interviews with surgeons. Because the preoperative process is complex and so little is known about surgeons’ practices and what motivates those practices, we felt that a qualitative approach would allow us to explore that complexity better than a quantitative survey.

Setting and participants

Surgeons were recruited from clinical practices in Baltimore, Maryland. We purposively recruited surgeons to maximize the diversity of our sample with the goal of hearing a wide range of practices and opinions. We recruited an approximately equal mix of academic and private practice surgeons, and a mix of general (including colorectal, vascular, oncologic, thoracic, endocrine, breast, and plastic) and non-general (including orthopedic, urologic, and otolaryngologic) surgical specialties. Additionally, we oversampled women and sought a mix of early-, mid-, and late-career surgeons.

We contacted surgeons from two local academic institutions via publically available email addresses. We were unable to locate publically available email addresses for local private practice surgeons, so we obtained their contact information with the assistance of the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network, a research consortium of area hospitals and health systems. All surgeons were located in and around Baltimore, Maryland. Surgeons were offered a small monetary incentive for participating, and they were interviewed in-person in a private setting that was convenient for them, typically their offices.

Interview guide

General topics for questioning included surgeons’ current PME practices and related training, surgical risk assessment, potential benefits and potential downsides for patients and others in the health care system, and ideas for improving the system. Each author was involved in developing the initial interview guide. As the study progressed, the interview guide underwent revisions to allow further exploration of new topics that had been raised in prior interviews. Additionally, semi-structured interviews allowed for topics not included in the guide to emerge and be explored. The final interview guide is shown in the Appendix.

Data collection and analysis

One investigator (KRR) conducted the interviews in person between June 2015 and May 2016. Just prior to the interview, participant characteristics were collected using a brief questionnaire. Interviews were audio-recorded and the recordings were transcribed verbatim. Identifying information was removed from interview transcripts.

The transcripts were initially analyzed using conventional thematic content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). A codebook of descriptive codes (also known as topical codes) was developed collaboratively by two authors (KRR and GC) as the transcripts were reviewed. The transcripts were coded using textual data analysis software (ATLAS.ti version 7, Scientific Software Development), which allowed coded segments to be compared to all other segments with the same code to look for emerging themes. The outcome of this type of thematic analysis is the identification of general themes (e.g., reassurance as a benefit of preoperative medical evaluation), which can then be used to construct new theory (e.g., as with grounded theory methodologies). The goal of our analysis was not to develop theory but to identify themes in the form of specific assertions representing practices and beliefs (Erickson 1986; Saldaña 2013). The initial stage of coding was ongoing during the time interviews were being conducted, and helped guide the determination that enough data had been collected (a concept known as thematic saturation) (Guest et al. 2006).

After the initial stage of thematic analysis, each of the transcripts was then re-coded for supporting and opposing instances of each theme (except for “practice variation” which we just described). We tabulated the number of interviews in which instances of each theme appeared (not necessarily mutually exclusive, as supporting and opposing instances of a theme could each appear in an interview). Each transcript was independently coded by two team members to enhance reliability, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved the study.

Results

We interviewed a total of 18 surgeons, whose demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. One-third of the surgeons were female, and the mean age and mean time since finishing their training was 43.4 years and 9.7 years, respectively. Surgeons were evenly split between academic and private practice, and slightly more than half (11/18) were general surgery specialties.

Practice variation

The variation in surgeons’ descriptions of their PME practices was striking. Each surgeon said they required an evaluation and some testing for a majority of their patients, typically directed by primary care physicians (PCPs) or preoperative clinics run by anesthesiology. However, some surgeons were selective about who would require these additional visits based on patient factors and operation factors, while others required these visits in all of their patients with no exceptions. Surgeons were split on whether they preferred PCPs or anesthesiologists direct the PME, and while most surgeons felt that either was adequate, some required patients to be seen separately by both. Some surgeons ordered necessary tests themselves, while others had consultants order them (sometimes at the discretion of the consultants, and other times dictated by the surgeons). Some surgeons required specialist involvement (e.g., cardiology) in certain cases, while others left that determination to the discretion of the clinician performing the PME. Some surgeons would require visits with several specialists in addition to a PCP visit for some patients, while others said that a specialist visit should obviate the need for a PCP visit. Most surgeons initiated the process of evaluation after the tentative decision for surgery had been made, and they added patients to the operating room schedule at that point. However, a few surgeons said they waited for the results of preoperative consults or tests before adding patients to the operating room schedule to make sure they were “cleared.”

Patient benefits and harms

Themes related to the benefits and harms of PME and representative quotations are shown in Table 2. Universally, surgeons believed that PME provided some benefit to at least some patients. The primary benefit that surgeons cited was the identification of occult conditions. Many shared stories of patients who appeared well but had serious pathology incidentally discovered in the PME, which was either able to be addressed (making surgery safer) or required surgery to be canceled (saving the patient an unnecessary or unsafe surgery). Surgeons also indicated that they believed the PME resulted in optimization or “fine tuning” of chronic conditions, although they were less specific in their evidence supporting this belief.

Surgeons generally agreed that PME was overall beneficial, though many acknowledged that the benefits typically accrue to a minority of patients and that most patients did not derive a direct medical benefit. Some surgeons pointed out that it is not possible to identify who will benefit ahead of time, and so PME that ends up not being beneficial is ultimately justified by the minority of cases where patients derive a medical benefit.

Even when the results of the PME are normal and do not alter the surgical plan, some surgeons believed that they were still worthwhile. In some cases, this was just because the surgeons like to “have those numbers.” In addition, they believed that normal test results and “another pair of eyes” reviewing the case were reassuring to patients as well as surgeons and anesthesiologists. Other potential patient benefits were mentioned less frequently, including as opportunities for education or to increase patient engagement, or just a reason for people who might not otherwise see a primary care doctor to do so.

The majority of surgeons denied that there could possibly be any medical harms from PME. While many of the surgeons explicitly recognized that PME essentially represents “screening” that patients may not otherwise receive if they were not considering surgery, they believed that anything identified through this screening (e.g., lab abnormalities or lung nodules) ultimately represented a benefit to patients. However, one surgeon cited the potential of falsely abnormal results to delay surgery and another specifically cited “overtreatment.”

Surgeons generally downplayed potential medical harms of the PME, but they largely recognized the inconvenience to patients of extra office visits and tests. Some mentioned that visits in preoperative clinics the day before surgery would require out-of-town patients to spend a night in a hotel. A number of surgeons mentioned that patients had brought up the inconvenience of the PME to them, although only one had ever heard a patient bring up out-of-pocket costs for extra office visits or tests.

Surgical risk assessment

Themes related to risk assessment and representative quotations are shown in Table 3. Universally, surgeons indicated that in their initial evaluation of patients, they performed their own assessment of patients’ surgical risk. For the most part, these assessments were informal, described as “a gestalt,” “the eyeball test,” or “spit balling.” Few had ever used a formal risk assessment tool or calculator, and none reported using them regularly. However, surgeons were generally confident in their ability to estimate risk. Two surgeons mentioned research indicating that surgeons’ gestalt is as good as a more formal risk assessment, and one even said that if their assessment differed from the consultant’s assessment that “I still trust myself more.”

Some surgeons found the risk assessment provided by the consultants performing the PME to be helpful, but most reported that it rarely affected their surgical plan. Most surgeons viewed the PME a task that had to be completed, and a majority of surgeons spontaneously used the terminology “cleared” or “clearance” to describe the assessment of the clinicians performing PME, reflecting this belief. This view is driven in part by the timing of the PME, which typically occurs after a tentative decision to have surgery has been made, so surgeons have already made an assessment that the benefits outweigh the risks. To this end, some surgeons explicitly said that they do not routinely review the notes provided by consulting clinicians, and that when there are problems that are going to delay or prevent surgery, they are contacted directly about them. So while other clinicians’ risk assessment is not routinely incorporated in the decision to have surgery, unanticipated problems discovered during the PME often result in the surgery being reconsidered.

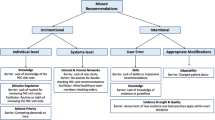

Drivers of current PME practice, potential improvements, and barriers to change

Themes related to drivers of current PME practice, potential improvements, and barriers to change and representative quotations are shown in Table 4. Most surgeons indicated that their requirements for preoperative testing and medical office visits were driven by hospital or anesthesiology requirements, although they were not always able to describe the specifics of those requirements. Many surgeons were focused on ensuring that anesthesiology’s requirements were met to ensure that cases were not canceled at the last minute, sometimes driving surgeons to order or request more than they thought was actually needed.

Most surgeons reported receiving very little formal training in how to perform the PME. Some of the general surgeons indicated that during their training, they were responsible for performing PME, so they gained some expertise and comfort in doing so, even if they had to “muddle through and figure it out.” On the other hand, most of the specialty surgeons indicated that they outsourced PME to primary care or anesthesia during their training, and so they never gained any experience or comfort with it.

Despite the variation and lack of training, most surgeons perceived that their practice was very similar to their colleagues’. In part, this related to hospital requirements that essentially standardized both their practice and their colleagues’ practice. However, several explicitly stated that they developed their current practice by observing and adopting that of their colleagues.

Many surgeons felt the PME reduced their malpractice risk, although this was not universal. Some indicated that the reduced risk was due to the PME leading to fewer complications, but many indicated that even in the case of non-preventable complications, the fact that another physician had “cleared” the patient for surgery would be protective.

Several surgeons indicated that they welcomed more standardization of the PME. Toward this end, several thought consensus guidelines would be helpful because they would reduce their uncertainty as to whether the patient had received an adequate PME and may even reduce the malpractice risk. However, several surgeons expressed skepticism that there was adequate evidence that a less resource-intensive PME process would be safe, although they indicated that more evidence could persuade them to change their practice.

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we elicited a comprehensive picture of surgeons’ views on PME. This study supplements prior studies, which were more narrowly focused either on testing in low-risk situations (Brown and Brown 2011; Patey et al. 2012) or medical consultations (Katz et al. 1998; Pausjenssen et al. 2008). For example, Brown and Brown (Brown and Brown 2011) conducted qualitative interviews with a diverse group of clinicians involved with preoperative testing (which included 7 surgeons out of 23 participants), and reported themes similar to ours with respect to satisfying hospitals’ and anesthesiologists’ requirements to avoid delays and cancellations, the potential medicolegal benefit of preoperative testing, and clinicians’ desire to have more standardization. However, most of our themes were not reported in these previous studies.

The results of this study have several important implications for future efforts to improve the process of PME. First, the PME should not primarily be viewed as simply providing a “risk assessment” or “risk stratification.” Surgeons are generally confident in their ability to estimate surgical risk, and since a tentative decision to proceed with surgery has already been made, simply providing another risk estimation will not routinely cause those decisions to be reconsidered. Rather, surgeons are looking for confirmation of their assessment (i.e., that they did not miss something important). Surgeons also want to assure that patients’ chronic conditions are being appropriately treated (i.e., “optimization” (Riggs and Segal 2016)), although how often conditions are actively being managed during this process is uncertain. Additionally, more research on who is best suited to direct the PME (i.e., PCPs or dedicated preoperative clinics) may be helpful, though as described by several surgeons in the study, it is likely unnecessarily redundant to have more than a single preoperative assessment.

Second, surgeons recognize that not every patient benefits from the PME, but they do believe that the process improves surgical outcomes overall. Further, while they are aware of the potential inconvenience of the process for patients, they do not believe that current evidence is adequate to justify changing their practice to require fewer tests or office visits. While some commentators have argued that evidence is sufficient to limit preoperative testing in many situations (Brateanu and Rothberg, 2015; Smetana 2015), high-quality evidence demonstrating the safety of less intensive PME is generally lacking (Balk et al. 2014) (with the exception of cataract surgery (Schein et al. 2000)). High-quality evidence demonstrating the safety of forgoing certain preoperative services and research examining the effect of less intensive PME on patient experience has the potential to change practices.

Finally, surgeons were very clear that one of their primary concerns is satisfying anesthesia and hospital requirements in order to avoid last minute cancellations. In part, this problem arises from the current workflow, where anesthesiologists may be assigned to cases on the day before or the day of surgery. Variation in the anesthesiologists’ opinion of what constitutes an appropriate PME may drive surgeons to be more exhaustive in terms of preoperative tests and consultations than they otherwise would be, in order to avoid last-minute delays and cancellations. More uniformity about what anesthesiologists expect would be welcomed by surgeons, as it would decrease anxiety about delays and cancellations and may lead to a less intensive PME. Consensus guidelines, even in the absence of more high-quality evidence, could drive more standardization and could even allay surgeons’ concerns about malpractice liability (Kirkpatrick and Burkman 2010). However, surgeons seem more attentive to local hospital policies than to national clinical guidelines, so future guidelines would likely have more impact if targeted at hospitals and anesthesiologists rather than surgeons or internists who perform PME.

This study has several limitations. First, we presented our themes as assertions, although qualitative research is not meant to be hypothesis testing, so these assertions warrant further quantitative testing in more representative samples. Second, all surgeons were currently practicing in a small geographic region, so their practices and beliefs could be specific to that region. Finally, we tried to avoid any specific focus on overuse or low-value care, though surgeons may have perceived that to be an implicit subject and tailored their interviews to avoid describing some low-value practices.

Conclusion

Surgeons’ PME practices vary dramatically, even within a single geographic area. While overuse in PME may be a legitimate concern, surgeons generally view PME as beneficial, so future research on PME and future reforms to the PME process should take into account surgeons’ views on the topic. More research into the safety of forgoing certain preoperative services and patient satisfaction with less intensive PME, and increasing standardization of the process through consensus guidelines may be options to decrease unwarranted variation and increase the value of PME.

Abbreviations

- PCP:

-

Primary care physician

- PME:

-

Preoperative medical evaluation

References

Balk EM, Earley A, Hadar N, Shah N, Trikalinos TA. Benefits and Harms of Routine Preoperative Testing: Comparative Effectiveness. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

Baxi SM, Lakin JR. Preoperative testing—a bridge to nowhere: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1272–3.

Brateanu A, Rothberg MB. Why do clinicians continue to order ‘routine preoperative tests’ despite the evidence? Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82(10):667–70.

Brown SR, Brown J. Why do physicians order unnecessary preoperative tests? A qualitative study. Fam Med. 2011;43(5):338–43.

Erickson F. Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In: Wittrock M, editor. Handbook of research on teaching. New York: Macmillan; 1986. p. 119–61.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Katz RI, Barnhart JM, Ho G, Hersch D, Dayan SS, Keehn L. A survey on the intended purposes and perceived utility of preoperative cardiology consultations. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(4):830–6.

Kirkpatrick DH, Burkman RT. Does standardization of care through clinical guidelines improve outcomes and reduce medical liability? Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1022–6.

Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PPT. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012;7:52.

Pausjenssen L, Ward HA, Card SE. An internist’s role in perioperative medicine: a survey of surgeons’ opinions. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:4.

Riggs KR, Segal JB. What is the rationale for preoperative medical evaluations? A closer look at surgical risk and common terminology. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(6):681–4.

Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2013.

Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of medical testing for cataract surgery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(3):168–75.

Smetana GW. The conundrum of unnecessary preoperative testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1359–61.

Thilen SR, Bryson CL, Reid RJ, Wijeysundera DN, Weaver EM, Treggiari MM. Patterns of preoperative consultation and surgical specialty in an integrated healthcare system. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(5):1028–37.

van Gelder FE, de Graaff JC, van Wolfswinkel L, van Klei WA. Preoperative testing in noncardiac surgery patients: a survey amongst European anaesthesiologists. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29(10):465–70.

Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Beattie W, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Outcomes and processes of care related to preoperative medical consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1365–74.

Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Beattie WS, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Variation in the practice of preoperative medical consultation for major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based study. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(1):25–34.

Funding

Dr. Riggs’s work on this study was funded by the Society of General Internal Medicine Founders’ Grant and by NIH grant T32 HL007180.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KR and GC conceived the study. All authors contributed to the study design. KR, GC, and ZB undertook the data analysis. KR drafted the manuscript which underwent revision by all other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved the study. All participants gave their verbal consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Final interview guide

-

1.

What are the operations you most commonly perform?

-

2.

What is your typical patient population like?

-

3.

What is your standard practice for “preops”? (Or whichever term is familiar.)

-

4.

Who usually performs those preops?

-

5.

What tests do you recommend or require be obtained as part of the preop?

-

6.

Do you order those tests? Why or why not?

-

7.

Do you request specialists to be involved in the preop? If so, how do you make that decision?

-

8.

How do you request a preop?

-

9.

How do you process preop notes and test results?

-

10.

Is there something specific in the preop note that you are looking for?

-

11.

(If not everyone gets a pre-op) How do you decide who doesn’t need a pre-op?

-

12.

Does your practice or institution have rules about preops? If so, what are they?

-

13.

Are there any clinical guidelines for preops that affect your practice? If so, what are they?

-

14.

How were you trained about doing preops?

-

15.

How does your current practice differ from the way you were trained?

-

16.

How do you think your practice differs from your colleagues? Others in your community?

-

17.

In your opinion, what are the benefits to the patients from preops?

-

18.

What are the potential downsides for the patients?

-

19.

Do you ever change your surgical plan based on the preop? If so, how?

-

20.

What are the benefits to you, the other providers involved, or the health system from preops? How do preops affects a surgeon’s risk of malpractice?

-

21.

What are the potential downsides to you or the health system from preops?

-

22.

Do anesthesiologists ever cancel cases because of inadequate preop? If so, examples?

-

23.

How comfortable do you feel in estimating a patient’s operative risk?

-

24.

How do you estimate a patient’s operative risk?

-

25.

Do patients express preferences or expectations regarding preops? If so, how?

-

26.

Do you have any memorable anecdotes about a patient who was impacted positively or negatively by a preop?

-

27.

Do you think there would be any way to make the preop system better?

-

28.

Anything else?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Riggs, K.R., Berger, Z.D., Makary, M.A. et al. Surgeons’ views on preoperative medical evaluation: a qualitative study. Perioper Med 6, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-017-0072-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-017-0072-5