Abstract

Background

Routine pre-operative tests for anesthesia management are often ordered by both anesthesiologists and surgeons for healthy patients undergoing low-risk surgery. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was developed to investigate determinants of behaviour and identify potential behaviour change interventions. In this study, the TDF is used to explore anaesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions of ordering routine tests for healthy patients undergoing low-risk surgery.

Methods

Sixteen clinicians (eleven anesthesiologists and five surgeons) throughout Ontario were recruited. An interview guide based on the TDF was developed to identify beliefs about pre-operative testing practices. Content analysis of physicians’ statements into the relevant theoretical domains was performed. Specific beliefs were identified by grouping similar utterances of the interview participants. Relevant domains were identified by noting the frequencies of the beliefs reported, presence of conflicting beliefs, and perceived influence on the performance of the behaviour under investigation.

Results

Seven of the twelve domains were identified as likely relevant to changing clinicians’ behaviour about pre-operative test ordering for anesthesia management. Key beliefs were identified within these domains including: conflicting comments about who was responsible for the test-ordering (Social/professional role and identity); inability to cancel tests ordered by fellow physicians (Beliefs about capabilities and social influences); and the problem with tests being completed before the anesthesiologists see the patient (Beliefs about capabilities and Environmental context and resources). Often, tests were ordered by an anesthesiologist based on who may be the attending anesthesiologist on the day of surgery while surgeons ordered tests they thought anesthesiologists may need (Social influences). There were also conflicting comments about the potential consequences associated with reducing testing, from negative (delay or cancel patients’ surgeries), to indifference (little or no change in patient outcomes), to positive (save money, avoid unnecessary investigations) (Beliefs about consequences). Further, while most agreed that they are motivated to reduce ordering unnecessary tests (Motivation and goals), there was still a report of a gap between their motivation and practice (Behavioural regulation).

Conclusion

We identified key factors that anesthesiologists and surgeons believe influence whether they order pre-operative tests routinely for anesthesia management for a healthy adults undergoing low-risk surgery. These beliefs identify potential individual, team, and organisation targets for behaviour change interventions to reduce unnecessary routine test ordering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pre-operative tests are ordered to aid in the management of surgical patients. These pre-operative tests provide information about the function of the biological systems that may not be directly affected by the surgical condition, but may be relevant to the perioperative course[1]. However, many pre-operative tests are routinely ordered for apparently healthy patients without any clinical indication, and the subsequent test results are rarely used[2]. In addition, unnecessary testing may lead physicians to pursue and treat borderline and false-positive laboratory abnormalities[3]. A randomized control study (RCT) of over 19,000 cataract patients found no benefit to routine pre-operative medical testing when stratified according to age, gender, or race of the patient, and most abnormalities in laboratory values could be predicted from patient’s history and physical exam[4]. Further, Chung et al. conducted an RCT of routine pre-operative testing in 1,057 ambulatory patients where one arm received pre-operative tests ordered according to the Ontario Pre-operative Testing Grid[5] and the other received no pre-operative tests routinely ordered for anesthesia management[6]. They reported no significant difference between rates of perioperative adverse events and the rates of adverse events 30 days after surgery between groups[6].

The Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society (CAS) has published guidelines to aid pre-admission teams about the appropriateness of certain tests prior to surgery[7]. They advocate that investigations should not be ordered on a routine basis, but should be based on the patient’s health status, drug therapy, and with consideration to the proposed surgical intervention[7]. However, in a study conducted by Hux et al. that looked at patterns of pre-operative chest x-rays and electrocardiogram—two tests commonly ordered routinely for anesthesia management—use in Ontario surgical patients, they reported considerable variation in testing rates in low-risk procedures across the province as well as within institutions[8]. In 50 Ontario hospitals, for low-risk (outpatient) procedures (cystoscopy, cataract removal, laparoscopic cholescystectomy, hysterectomy), hospital-specific rates of patients receiving chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, or both ranged from less than 1% to 98%[8]. These findings suggest that factors other than evidence of patient benefit may influence test ordering behaviour.

Failure to convert recommendations into practice is often not related to the content or quality of the guideline but to difficulties in changing established behaviours of the clinicians and institutions[9]. Canadian surgical patients encounter a number of healthcare providers responsible for their experience in the healthcare system including the family physician writing the referral, the attending surgeon, the attending anaesthesiologist, nursing staff, and the myriad of professionals in the pre-admissions clinic. Translating guidelines into clinical practice is notoriously difficult when one healthcare professional has decision-making autonomy; it can be even more so when a group of professionals are responsible, as is the case with pre-operative test ordering. While the guidelines for pre-operative testing are recommendations for anaesthesiologists, other clinicians can and do order pre-operative tests. Bryson reported that surgeons were responsible for 80% of the test ordering that were in non-compliance with the Ontario Pre-operative Testing Grid at the Ottawa Hospital[10]. When many groups of professionals can be the potential target of behaviour change interventions, understanding the thoughts and opinions of the key clinical decision makers about the behaviour in question becomes important. However, much of the work examining health practitioner behaviour change has, to date, been largely atheoretical[11–14]. Using theory for identifying determinants of behaviour and selecting interventions can increase the likelihood of the complex interventions being appropriate[15]. Empirically-supported theories of behaviour change may thus inform attempts to change test-ordering behaviour. Establishing a better theoretical understanding of healthcare professional behaviours and their perceptions of team behaviours may increase the likely success of interventions to change clinical practice.

Psychological theories have long been used to understand, predict, or generate behaviour change in healthcare providers[11, 16–19]. Commonly, researchers have tested a single or small number of theories. As a result, only a small range of the potential influences on behaviour are tested. Such studies may be uninformative if the key determinants of the behaviour under question are not represented in the tested theories. Currently, there is little rationale to guide choice of potentially relevant theories. In an attempt to address these problems, Michie et al.[20] applied a systematic consensus approach to develop a framework grounded in psychological theory that simplifies theories relevant to behaviour change. The consensus identified 12 theoretical domains from 33 theories and 128 constructs that may explain health-related behaviour change. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) can be used to inform the choice of potential behaviour change techniques to develop interventions as well as to investigate determinants of behaviour[20].

In this study, we used the TDF to systematically examine the beliefs of anaesthesiologists and surgeons about the use of pre-operative testing routinely ordered for anesthesia management in healthy patients undergoing low-risk surgical procedures. This article is one in a series of articles documenting the development and use of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to advance the science of implementation research[21–24]. Greater detail about the TDF can be found in the introductory article of this series[23].

Methods

Design

This was an interview study using semi-structured interviews with anaesthesiologists and surgeons.

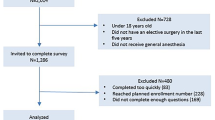

Participants

Participants were selected using a snowball sampling strategy supplemented with purposive sampling techniques. The snowball sampling was used to identify key informants likely to be knowledgeable about the topic being discussed. We identified two or three individuals who would be willing to participate and subsequently requested that they identify additional two individuals they believed would provide valuable information regarding preoperative test ordering practice for anesthesia management.

The criteria used to select the potential interviewees were that they cared for individuals for whom the behaviour under investigation is relevant and were representative of community and academic hospitals. Additionally, in an attempt to avoid premature saturation, we asked the participants to recommend additional anesthesiologists with differing opinions. Because anesthesiologists in Ontario may staff both the pre-admission clinics and the operation rooms on a rotating basis, they could provide their experience from both roles when we asked questions about ordering and reviewing tests. While we had originally planned on only interviewing anesthesiologists (as they are primarily responsible for ordering tests relevant to anesthesia management), surgeons were added to the sampling after six interviews with anesthesiologists. It became apparent after these six interviews the strong influence surgeons had on the test ordering practice of the anesthesiologists and we decided to include them in the study. Our sampling criteria for the surgeons was similar to that of the anesthesiologist in that the surgeons cared for individuals for whom the behaviour under investigation is relevant, however we did not purposively sample by different surgical subspecialty. We continued to add both anesthesiologists and surgeons and used the concept of data saturation to determine when we no longer needed to continue interviewing. In other words, we conducted interviews with each group until no new information was being offered[25], which occurred after 16 interviews (anesthesiologists and surgeons).

Interview topic guide

The behaviour of interest was ordering of pre-operative tests for anesthesia management (chest x-ray (CXR) and electrocardiographs (ECG)) in a healthy patient having low-risk surgery (knee arthroscopy, laparoscopic cholescystectomy, or cataract removal, lens replacement, and similar type surgeries). Healthy patients were defined as those patients without any co-morbidity or additional medical conditions that could complicate anesthesia management and perioperative care other than the ailment for which surgery is required. An interview topic guide was developed based on the Theoretical Domains Framework to elicit beliefs about each domain for the behaviour, and obtain greater detail about the role of the domain in influencing the behaviour[18]. With advice of a content expert in the field of anesthesia (GLB), the guide was adapted from the original framework[20] to be appropriate to the specific behaviour and clinical context. Questions about ordering and reviewing tests for anesthesia management were included in the interview guide because these two behaviours form part of a continuum; reviewing tests typically occurs on the day of surgery, several days after the tests were originally ordered. We wanted to determine if and why clinicians ordered tests for other clinicians but may not review tests ordered for them on the day of surgery. After pilot testing with two anesthesiologists, wording of some questions from the original TDF had to be modified to fit the context of the behaviour. Subsequent piloting with a further two anesthesiologists resulted in additional wording changes to enhance clarity of one question (See Additional file1 for Interview Topic Guide).

Procedure

Participants were contacted in writing and invited for an interview at a time convenient to them. All interviews (conducted by AMP) were conducted by phone or in person. The interviews were digitally recorded and lasted between 14 and 46 minutes. The recordings were transcribed and anonymised.

Analysis

Two researchers (AMP, RI) coded interview participants’ responses into the relevant theoretical domains. Two pilot interviews were used to formulate a coding strategy. The first pilot interview was coded by two researchers in tandem to develop the coding strategy, and the second was used to ensure the two coders were comfortable with the strategy developed from the first. Subsequent coding of the remaining interviews was completed independently and Fleiss’s Kappa (κ) was calculated for all domains and interviews to assess whether the two researchers coded the same response into the same domain[26, 27]. Responses that were coded in different domains by the researchers were discussed to establish consensus. In instances where single domain allocation agreement could not be reached, researchers agreed that the response could be placed in both domains.

One researcher (AMP) generated statements that represented the specific beliefs from each participant’s responses that captured the core thought and continued this process for every response. A specific belief is a statement that provides detail about the perceived role of the domain in influencing the behaviour[18]. The belief statement was worded to convey a meaning that was common to multiple utterances by interview participants. When a statement was considered similar to a previously identified statement, both were coded as two instances of the same belief. Specific beliefs that centred on the same theme or were polar opposites of a theme were grouped together. This strategy was reviewed by the second researcher (RI) to ensure accurate representation of content.

Relevant domains were identified through consensus discussion between the two researchers (AMP, RI) and confirmed by a health psychologist (JJF). Briefly, three factors were considered when identifying key domains: frequency of the beliefs across interviews; presence of conflicting beliefs; and perceived strength of the beliefs impacting the behaviour. All of these factors were considered concurrently in establishing domain relevance. For example, if the belief that my emotions do not influence whether or not I order routine tests was consistently reported, it was concluded that the Emotion domain was not relevant to the behaviour. In contrast, if the majority of respondents in a study reported the belief that it is very easy to order tests then the Beliefs about capabilities domain would have been selected as relevant because of its content and the impact that it might have on physicians’ practice. Similarly Beliefs about consequences would be identified as a key domain if conflicting statements about potential consequences associated with the behaviour ranged from negative (delay or cancel patient surgery) to indifference (little or no change in patient outcome) to positive (avoid unnecessary investigation).

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Results

Participants

Sixteen participants, eleven anesthesiologists (9 male; 2 female) and five surgeons (all males), from community (n = 3) and academic hospitals (n = 5) in six health regions throughout Ontario were recruited to participate in the semi-structured interviews. The clinicians’ experience as a specialist ranged in years from 2.5 to 22 (mean ± SD, 10.72 ± 5.16).

Interrater reliability

A total of 459 utterances from the 16 interviews were coded into the 12 domains. Interrater reliability for the coder across all interviews and domains had ‘almost perfect agreement’[28] (κ = 0.84; 95% CI 0.807 to 0.878). Further, although initial interrater reliability was calculated, all disagreements between researchers were resolved through consensus.

Key themes identified within relevant domains

Key themes emerging from the interviews with anesthesiologists and surgeons were categorised within seven theoretical domains: Social/professional role and identity, Beliefs about capabilities, Beliefs about consequences, Environmental context and resources, Social influences, Behavioural regulation, and Nature of the behaviour (Table 1).

While both groups felt that they did not need to order or review a CXR or ECG to adequately do their job when performing a low-risk surgical procedure on a healthy patient, they made conflicting comments as to who exactly was responsible for ordering the pre-operative tests and responses within each professional group varied (Social/professional role and identity). For example, several anesthesiologists stated that they should have complete autonomy as to what tests should be ordered whereas others noted that within their hospital it was not their responsibility to order the pre-operative tests (Nature of the behaviour, Social/professional role and identity, Environmental context and resources). Conversely, some surgeons noted that pre-operative test ordering was the responsibility of the anesthesiologists, while others mentioned that they were the most responsible physician in the operating room and as such had the ultimate responsibility to understand the whole picture (Social/professional role and identity).

Both anesthesiologist and surgeons reported that it was very easy to order any pre-operative test they wanted—they just ticked a box on the admitting forms (Beliefs about capabilities, Environmental context and resources). However, anesthesiologists noted that there was a problem with their inability to cancel tests ordered by the attending surgeon, because they did not know the initial reasoning behind the surgeon ordering the test (Beliefs about capabilities, Social influences). Further, they mentioned that often when surgeons ordered pre-operative tests, the tests were usually completed before the anesthesiologist sees the patient (Beliefs about capabilities, Environmental context and resources).

Interestingly, anesthesiologists noted that they often ordered tests they did not think necessary to prevent a cancelled surgery if those tests were required by a colleague with different preferences regarding testing for anesthesia management (Beliefs about capabilities, Social influences, Beliefs about consequences). They also noted that because they work with a team there is often an understanding among their colleagues as to what tests are required and they tend to be conservative and order more, to cater for majority views (Social influences, Beliefs about capabilities). The surgeons gave conflicting information about colleague influence. They stated that they rely on the anesthesiologists to order the necessary pre-operative tests and listen to their other team member before making a decision regarding what tests to order, but mentioned that no one would question their request for certain tests; staff would just follow the surgeons’ requests (Social influences).

Both surgeons and anesthesiologists reported variable practice in their personal review of pre-operative tests before commencing with anesthesia and surgery (Nature of the behaviour). There were also conflicting comments about the potential consequences associated with reducing testing (Beliefs about consequences). Both anesthesiologist and surgeons agreed that routine tests are a waste of time and money, unnecessary, and rarely provide any useful information. They stated that routine testing may result in false positives that require investigation, and reducing test ordering would avoid unnecessary investigations and delays. Yet, they also mentioned that routine testing saves patients' time and if routine tests are not ordered, a patient's surgery may get cancelled or miss an underlying condition that may complicate surgery and ensures the patient is fit for the surgery.

Both anesthesiologists and surgeons identified factors within their environment that affected their decision to order pre-operative tests (Environmental context and resources). There was considerable disagreement as to whether time constraint was a factor in test ordering practice.

There were also reports of a gap between their motivation and practice (Behavioural regulation). Both anesthesiologists and surgeons mentioned if hospitals made sure that all pre-operative testing was conducted by only anesthesiologists and took the ordering out of the hands of the surgeons, unnecessary routine testing could be reduced.

Domains reported not relevant

Five domains appeared to be less relevant: knowledge, motivation and goals, skills, memory, attention and decision processes, emotion (Table 2). The majority of anesthesiologists and surgeons were aware of the guidelines and knew they were supported by evidence-based research (Knowledge). Both groups reported that they didn’t feel obligated to order tests for anesthesia management for a low-risk surgery, and some stated that routinely ordering tests was not an important part of their pre-operative evaluation (Motivation and goals). In addition, they stated that there was no set of specific skills required to order pre-operative test and that nurses, general practitioners, and other physicians (internists) can order them if appropriately trained (Skills). When asked about their Memory, attention, and decision processes, anesthesiologist and surgeons stated that they focus mainly on patient history and medical condition when deciding what tests may be required at the time of a patient’s surgery. Further, all respondents interviewed stated that their own emotions would not influence whether they ordered pre-operative tests or not (Emotion).

Discussion

This study applied the TDF[20] to help understand the influences of pre-operative test ordering practices for anesthesia management in healthy patients by anesthesiologists and surgeons. The results show that the most frequently mentioned influences on the clinicians’ test ordering practice were categorised primarily in the Social/professional role and identity, Beliefs about capabilities, Beliefs about consequences, Environmental context and resources, and Social influences domains, and centred around two key issues. First, the lack of clarity by hospital management and lack of written policies as to who was ultimately responsible for ordering the tests (Social/professional role and identity, and Environmental context and resources) is a considerable factor influencing whether or not they order routine pre-operative tests. Respondents reported that hospitals commonly either failed to identify which group was specifically responsible for test ordering or identified surgeons as the group responsible for test ordering. Further, the existence of hospital directives varied from hospital to hospital throughout the province (Environmental context and resources). The finding that surgeons often order pre-operative tests according to hospital policies seems counterintuitive because the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society is the professional body making the recommendations and state that policies regarding pre-anesthetic assessment should be established by the department of anesthesia[7]. Yet, the anesthesiologists and surgeons interviewed report this finding as accurate and is further supported by evidence documented by Bryson et al.[29]. The likelihood that an alternative professional group would review another’s guidelines is rare because they struggle to keep up-to-date with their own ever-changing evidence-based practice. So how do we ensure that those responsible obtain the best and most current evidence? A directive by hospital management that is supported by the professional groups involved, as to which group holds the role and responsible for ordering the tests required for anesthesia management would likely reduce confusion and encourage greater consistency in test ordering practices.

Second, evidence of the inter-professional influences among the attending surgeon performing the surgery, the anesthesiologist at pre-admission ordering the tests, and attending anesthesiologist providing intraoperative care was reported by the vast majority of respondents (Social/professional role and identity, Beliefs about capabilities, Belief about consequences, and Social influences). The lack of clarity about who is responsible for routine test ordering appears to lead to a propensity to order tests ‘ just in case’ they are expected by another colleague. A surgeon may order the tests ‘ in case’ the attending anesthesiologist needs it and in hopes that the patient will move smoothly through the pre-admission assessment process. The anesthesiologist who sees the patient prior to the surgery orders the tests ‘ in case’ the attending anesthesiologist needs them and could not cancel tests ordered by the surgeon because they have not identified the reason for ordering the tests. Furthermore, the anesthesiologists interviewed reported they seldom reviewed test results when caring for low-risk patients in the operating room. The interesting thing about the team influence is that although anesthesiologists and surgeons greatly influence whether pre-operative test are ordered by another team member, these clinicians rarely have direct contact with one another and communication is difficult. A study by Lingard et al. examined intraoperative communication in a surgical team comprising surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and trainees[30]. They found marked differences in the professionals’ perceptions around issues of role authority, motivation, and value with respect to communication among team members. Although their study looked at four professional groups, their findings are consistent with ours in identifying a problem in the lack of clarity relating to roles of surgeons and anesthesiologists. They suggest that communications of these team members are probably motivated by some combination of concern for the patient, the day’s schedule, ethical issues, economic implications, and many other factors[30], an idea that is reflected in our finding of professionals ordering test just ‘ in case’ the tests are needed. Further, communication with respect to pre-operative testing is additionally complicated by the surgeons’ and anesthesiologists’ separation by time and space.

This study is one of the first to attempt to examine why anesthesiologists and surgeons order routine pre-operative tests when no clinical indicators exist. There has been a large body of work reporting pre-operative testing practices[2, 4, 6, 10, 31–33]. However, few attempt to explain why clinicians do one thing when the guidelines recommend another with respect to test ordering for anesthesia management[7]. A systematic review by Munro et al. reported that the value of pre-operative ECGs in predicting postoperative cardiac complications seems to be very small, and the indirect evidence suggests that routinely recorded pre-operative ECGs as a baseline measure are likely to be of little or no value[34]. Further the anesthesiologists and surgeons interviewed appear to lend credence to this report. Yet, reports continue to document unnecessary routine test ordering[2, 4, 6, 10, 31–33], and we have attempted to ask those clinicians involved why unnecessary tests for anesthesia management continue to be ordered. Bryson et al. was the only paper reviewed to suggest a need to change ‘ established behaviour’ that should include not only anesthesiologists but surgical colleagues and clinic personnel[10]. By examining the views of the clinical decision makers (anesthesiologists and surgeons) in a theory-based systematic manner, we have identified the theoretical domains we propose best predict pre-operative test ordering for anesthesia management when assessing healthy patients undergoing low-risk surgeries.

Seven domains were considered potentially important for changing test-ordering behaviour (Social/professional role and identity, Beliefs about capabilities, Beliefs about consequences, Environmental context and resources, Social influences, Behavioural regulation, Nature of the behaviour), while five were consistently identified as not relevant (Knowledge, Skills, Emotion, Motivation and goals, and Memory, attention and decision processes). Of the seven identified the five that appeared to be the most influential, based on the frequency of utterances coded and content of the responses, were Social/professional role and identity, Beliefs about capabilities, Beliefs about consequences, Environmental context and resources, and Social influences. The TDF is a relatively new framework that attempts to help understand clinical behaviour from a psychological perspective. Previous attempts to understand clinicans’ behaviour has either been atheoretical[11–14] or have used a limited number of theories[35–37] with varying effectiveness. Ideally, researchers should have ready access to a definitive set of theoretical explanations of behaviour change and a means of identifying which are relevant to particular contexts[20]. The TDF allow for a categorisation of respondents’ views in a theoretically-based systematic way that attempts to encompass a broad range of psychology theories without favouring a specific one.

While this study has provided valuable insight into the factors that may influence routine test ordering practices, there were several limitations. It is possible that saturation could have been prematurely reached if participants recommended interviewing others with similar opinions. In an attempt to avoid this, one of the criteria used in our purposive sampling was to ask the participants to recommend additional anesthesiologists with differing opinions. Subsequently, our results show that there was evidence of differing opinions from the anesthesiologists and surgeons about order test routinely ordered for anesthesia management.

Identification of themes does not provide evidence of the actual influences on clinical practice. These are merely clinicians’ views about what might influence their test ordering behaviour. Although interview studies are required in the exploratory stages of research in this field, different research designs would be required to establish which of these factors could be key to changing practice.

In this study the interview guide used a combination of questions that elicited descriptive and diagnostic responses (e.g., ‘ What thought processes might guide your decision to order pre-operative test for a patient having a low-risk surgery?’ is descriptive, whereas ‘ Are you confident that you are able to perform a pre-operative evaluation for a low-risk surgery without pre-operative tests?’ is diagnostic). It thus required further interpretation by the research team to decide whether a descriptive response represented a barrier to changing practice. For studies that use the TDF for problem analysis, it may be preferable to use more questions of the diagnostic kind.

Our study has shown that in various hospitals across the province of Ontario anesthesiologists are often not the professional responsible for ordering the pre-operative tests, even though the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society has published guidelines directing this aspect of perioperative care. Interviewing surgeons in addition to anesthesiologists strengthened our findings because it gave us the perspectives from both key professional groups responsible for ordering pre-operative test. It also identified the link between attending surgeon, assessing anesthesiologist, and attending anesthesiologist as an important social influence of pre-operative test ordering. Additional strength in our findings was that even though the two groups differ in their role in the care of patients, their responses around pre-operative test order practice largely converged. Both groups throughout the province repeatedly identified the same issues of concern. Recently, there have been a numbers of studies examining the inter-professional dynamics within a team of healthcare providers[30, 38–41] but further work is necessary to better understand the inter-professional dynamics of a healthcare team. Developing an intervention that would take into consideration the roles of all personnel involved in the care of a patient undergoing low-risk surgery has the greatest likelihood of being successful and should be developed using the domains identified in this study; in particular social/professional role and identity, beliefs about consequences, environmental context and resources and social influence.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to attempt to examine why anesthesiologists and surgeons order routine pre-operative tests. Our results identified potential influences, as defined by the TDF, upon test ordering behaviour of anaesthesiologists and surgeons when clinical indictors are not present. It offers a possible explanation to the test ordering differences reported by Hux et al.[8] and may help explain why routine tests are continually ordered when evidence shows their lack of value for perioperative management[2, 4, 29, 32]. Our findings can be used to develop a confirmatory predictive study to further explore determinants of routine pre-operative test order practice by developing a questionnaire for the key professionals based on the domains and content of the interviews. In addition, the results can be used to develop an intervention using intervention mapping directly from the domains[42]. By using the TDF, our study provides a theory-driven basis to identify predictors of clinician behaviour as well as generate possible interventions for the reduction of unnecessary pre-operative tests routinely ordered for anesthesia management.

Authors' information

JMG holds a Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. The Canada PRIME Plus team is an international collaboration of researchers consisting of health services researchers, health psychologists and statisticians.

Abbreviations

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- ECGs:

-

Electrocardiographs

- CXRs:

-

Chest X-rays

- A#:

-

Anesthesiologist

- S#:

-

Surgeon.

References

Valchanov KP, Steel A: Preoperative investigation of the surgical patient. Surgery (Oxford). 2008, 26: 363-8. 10.1016/j.mpsur.2008.07.002.

Thanh NX, Rashiq S, Jonsson E: Routine preoperative electrocardiogram and chest x-ray prior to elective surgery in Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthqsie. 2010, 57: 127-33. 10.1007/s12630-009-9233-4.

Roizen MF: Preoperative laboratory testing: necessary or overkill?. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2004, 51 (90001): 13-Can Anes Soc

Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, Tielsch JM, Lubomski LH, Feldman MA, Petty BG, Steinberg EP: The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342 (3): 168-175. 10.1056/NEJM200001203420304.

Badner N, Bryson G, Kashin B, Mensour M, Riegert D, van Vlymen J, Wong D: Ontario Preoperative testing grid. 2004, Available from URL;http://gacguidelines.ca/pdfs/tools/Ontario%20Preoperative%20Testing%20Grid.pdf, Endorsed by the Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee,

Chung F, Yuan H, Yin L, Vairavanathan S, Wong DT: Elimination of preoperative testing in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2009, 108: 467-10.1213/ane.0b013e318176bc19.

Merchant R, Bosenberg C, Brown K, Chartrand D, Dain S, Dobson J, Kurrek M, LeDez K, Morgan P, Penner M: Guidelines to the Practice of Anesthesia Revised Edition 2011 - Guide d’exercice de l'anesthésie Édition révisée 2011. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2011, 58: 74-107. 10.1007/s12630-010-9416-z.

Hux J: Preoperative testing prior to elective surgery. Hospital Quarterly. 2003, 6: 27-

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A: Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 1997, 157: 408-

Bryson GL, Wyand A, Bragg PR: Preoperative testing is inconsistent with published guidelines and rarely changes management [Les tests preoperatoires ne correspondent pas aux directives publiees et modifient rarement la ligne de conduite]. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2006, 53: 236-41. 10.1007/BF03022208.

Walker AE, Grimshaw J, Johnston M, Pitts N, Steen N, Eccles M: PRIME - PRocess modelling in ImpleMEntation research: selecting a theoretical basis for interventions to change clinical practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003, 3: 22-10.1186/1472-6963-3-22.

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA: Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998, 317: 465-10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465.

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB: Changing physician performance. JAMA. 1995, 274: 700-10.1001/jama.1995.03530090032018.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O'Brien MA, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2006, CD000259-10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2. 2

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2008, 337: a1655-10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Bonetti D, Pitts NB, Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Johnston M, Steen N, Glidewell L, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Clarkson JE: Applying psychological theory to evidence-based clinical practice: identifying factors predictive of taking intra-oral radiographs. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63: 1889-99. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.005.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N: Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 107-12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002.

Francis JJ, Stockton C, Eccles MP, Johnston M, Cuthbertson BH, Grimshaw JM, Hyde C, Tinmouth A, Stanworth SJ: Evidence-based selection of theories for designing behaviour change interventions: Using methods based on theoretical construct domains to understand clinicians' blood transfusion behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 2009, 14: 625-46. 10.1348/135910708X397025.

Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J: Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation Science. 2008, 3: 36-10.1186/1748-5908-3-36.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A: Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005, 14: 26-10.1136/qshc.2004.011155.

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S: Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science. 2012, 7: 37-10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

French S, Green S, O'Connor D, McKenzie J, Francis J, Michie S, Buchbinder R, Schattner P, Spike N, Grimshaw J: Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation Science. 2012, 7: 38-10.1186/1748-5908-7-38.

Francis J, O'Connor D, Curran J: Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implementation Science. 2012, 7: 35-10.1186/1748-5908-7-35.

Beenstock J, Sniehotta F, White M, Bell R, Milne E, Araujo-Soares V: What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking?. A cross-sectional survey of perceived implementation difficulties among midwives in the northeast of England. Implementation Science. 2012, 7: 36-

Patton MQ: Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 2002, Sage Publications, Inc

Fleiss JL: Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971, 76: 378-

Fleiss JL: The measurement of interrater agreement. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 1981, 2: 212-36.

Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977, 33: 159-10.2307/2529310.

Bryson GL, Wyand A, Bragg PR: Preoperative testing is inconsistent with published guidelines and rarely changes management. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthqsie. 2006, 53: 236-41. 10.1007/BF03022208.

Lingard L, Reznick R, DeVito I, Espin S: Forming professional identities on the health care team: discursive constructions of the ‘other’ in the operating room. Medical education. 2002, 36: 728-34. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01271.x.

Imasogie N, Wong DT, Luk K, Chung F: Elimination of routine testing in patients undergoing cataract surgery allows substantial savings in laboratory costs. A brief report [L'elimination des tests de routine, avant l'operation de la cataracte, permet de reduire de facon importante les depenses de laboratoire. Un rapport sommaire.]. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2003, 50: 246-8. 10.1007/BF03017792.

Finegan BA, Rashiq S, McAlister FA, O'Connor P: Selective ordering of preoperative investigations by anesthesiologists reduces the number and cost of tests. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthqsie. 2005, 52: 575-80. 10.1007/BF03015765.

Archer C, Levy AR, McGregor M: Value of routine preoperative chest x-rays: a meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthqsie. 1993, 40: 1022-7. 10.1007/BF03009471.

Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J: Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 1997, 1 (12): 1-62.

Godin G, Conner M, Sheeran P: Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: The role of moral norm. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005, 44: 497-512. 10.1348/014466604X17452.

Daneault S, Beaudry M, Godin G: Psychosocial determinants of the intention of nurses and dietitians to recommend breastfeeding. Can J Public Health. 2004, 95: 151-4.

Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, Steen N, Pitts NB, Thomas R, Glidewell E, MacLennan G, Bonetti D, Walker A: Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: Identifying factors predictive of managing upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics. Implementation Science. 2007, 2: 26-10.1186/1748-5908-2-26.

West MA, Poulton BC: A failure of function: teamwork in primary health care. J Interprof Care. 1997, 11: 205-16. 10.3109/13561829709014912.

West MA, Borrill CS, Dawson JF, Brodbeck F, Shapiro DA, Haward B: Leadership clarity and team innovation in health care. The Leadership Quarterly. 2003, 14: 393-410. 10.1016/S1048-9843(03)00044-4.

Leipzig RM, Hyer K, Ek K, Wallenstein S, Vezina ML, Fairchild S, Cassel CK, Howe JL: Attitudes toward working on interdisciplinary healthcare teams: a comparison by discipline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002, 50: 1141-8. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50274.x.

Eccles MP, Hrisos S, Francis JJ, Stamp E, Johnston M, Hawthorne G, Steen N, Grimshaw JM, Elovainio M, Presseau J: Instrument development, data collection and characteristics of practices, staff and measures in the Improving Quality of Care in Diabetes (iQuaD) Study. Implementation Science. 2011, 6: 61-10.1186/1748-5908-6-61.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis JJ, Hardeman W, Eccles MP: From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology: an international review. 2008, 57: 660-80. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not be shared by the funding body. We would like to that the participating anaesthesiologists and surgeons for their contribution to this study. The Canada PRIME Plus research team includes Jeremy Grimshaw, Michelle Driedger, Martin Eccles, Jill Francis, Gaston Godin, Jan Hux, Marie Johnston, France Légaré, Louise Lemyre, Marie-Pascale Pomey, and Anne Sales.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

Martin Eccles is Co-Editor in Chief of Implementation Science; Anne Sales is an associate editor of Implementation Science; Jeremy Grimshaw and France Légaré are members of the Editorial Board of Implementation Science.

Authors' contributions

JMG, JJF and the Canada PRIME Plus team conceived the study. AMP, JMG contributed to the daily running of the study. JJF oversaw the analysis which was conducted by AMP and RI. GLB provided content expertise in the filed of Anesthesiology. AMP wrote the manuscript and the authors listed commented on the sequential drafts of the paper and agreed upon the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Patey, A.M., Islam, R., Francis, J.J. et al. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implementation Sci 7, 52 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-52

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-52