Abstract

Background

Physical activity (PA) plays an important role in optimizing health outcomes throughout pregnancy. In many low-income countries, including Nepal, data on the associations between PA and pregnancy outcomes are scarce, likely due to the lack of validated questionnaires for assessing PA in this population. Here we aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of an adapted version of Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) among a sample of pregnant women in Nepal.

Methods

A cohort of pregnant women (N=101; age 25.9±4.1 years) was recruited from a tertiary, peri-urban hospital in Nepal. An adapted Nepali version of GPAQ was administered to gather information about sedentary behavior (SB) as well as moderate and vigorous PA across work/domestic tasks, travel (walking/bicycling), and recreational activities, and was administered twice and a month apart in both the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Responses on GPAQ were used to determine SB (min/day) and total moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA; min/week) across all domains. GPAQ was validated against PA data collected by a triaxial accelerometer (Axivity AX3; UK) worn by a subset of the subjects (n=21) for seven consecutive days in the 2nd trimester. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and Spearman’s rho were used to assess the reliability and validity of GPAQ.

Results

Almost all of the PA in the sample was attributed to moderate activity during work/domestic tasks or travel. On average, total MVPA was higher by 50 minutes/week in the 2nd trimester as compared to the 3rd trimester. Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, almost all of the participants were classified as having a low or moderate level of PA. PA scores for all domains showed moderate to good reliability across both the 2nd and 3rd trimesters, with ICCs ranging from 0.45 (95%CI: (0.17, 0.64)) for travel PA at 2nd trimester to 0.69 (95%CI: (0.51, 0.80)) for travel PA at 3rd trimester. Reliability for total MVPA was higher in the 3rd trimester compared to 2nd trimester [ICCs 0.62 (0.40, 0.75) vs. 0.55 (0.32, 0.70)], whereas the opposite was true for SB [ICCs 0.48 (0.19, 0.67) vs. 0.64 (0.46, 0.76)]. There was moderate agreement between the GPAQ and accelerometer for total MVPA (rho = 0.42; p value <0.05) while the agreement between the two was poor for SB (rho= 0.28; p value >0.05).

Conclusions

The modified GPAQ appears to be a reliable and valid tool for assessing moderate PA, but not SB, among pregnant women in Nepal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical activity (PA) plays an important role in optimizing health outcomes throughout pregnancy. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that pregnant women participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity PA per week [1], as this may be protective against adverse pregnancy outcomes including excessive gestational weight gain and gestational diabetes mellitus [2, 3]. PA that incorporates both aerobic and resistance exercises can positively impact cardiorespiratory health during pregnancy [4], and PA is generally related to greater overall health and quality of life among adults [5, 6]. Valid and reliable tools are essential to assess PA patterns and their relationship to health outcomes in pregnancy [7]. In population-based studies, questionnaires are the most commonly used instrument to assess and measure PA, as they are relatively quick, low-cost, and easy to administer among large populations [7]. In many low-income countries, including Nepal, data on the associations between PA and pregnancy outcomes are scarce, likely due to the lack of validated questionnaires for assessing PA in this population.

Globally, multiple questionnaires have been utilized to assess PA during pregnancy, including the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ) [8], the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [9], and the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [10]. The PPAQ was developed and evaluated for use during pregnancy [8], and has shown adequate validity and reliability across pregnant populations in several countries [11], though its applicability within low to middle-income countries (LMICs) remains unknown. The IPAQ was developed in the late 1990s to help standardize the measurement of health-related PA across 12 countries [9], but was found to have poor agreement and correlation with accelerometry measures during pregnancy [9]. In 2002, the WHO created the GPAQ, a modified version of the IPAQ, in response to a greater cross-cultural interest in understanding the relationship between PA and health outcomes [10]. The GPAQ has the advantage of capturing and assessing self–reported PA across three domains: work/domestic tasks, travel/transportation, and leisure/recreation tasks. The WHO specifically developed the GPAQ for PA surveillance in LMICs [10], where it has since been extensively used and validated [12, 13], including among non-pregnant adults within Nepal [9, 10, 14,15,16]. While the GPAQ has been used to assess PA during pregnancy in a few studies, [17, 18] validation studies in pregnant populations remain limited [19].

Notably, many studies assessing PA during pregnancy have not utilized validated measurement tools when evaluating associations between PA and health outcomes [20]. It is important that self-report PA questionnaires, such as the GPAQ, are validated against objective measures of PA, such as accelerometry, within each specific population that they will be utilized [7]. Currently, the validity of the GPAQ has only been explored among a single population of pregnant women in South Africa, where it was found to overestimate PA and underestimate sedentary behavior (SB) [19]. Here, we aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of an adapted version of the GPAQ among pregnant women in a periurban setting in Nepal.

Methods

Study design

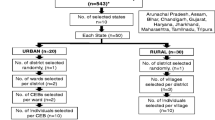

This prospective cohort study recruited 101 pregnant women attending the Obstetric Outpatient Department (OPD) at Dhulikhel Hospital in Dhulikhel, Nepal, for antenatal care (ANC) between January 2019 and January 2020. Women were enrolled during their 1st trimester ANC visit (5-14 weeks of gestation) and followed through the 2nd and 3rd trimester, up until six weeks postpartum. The primary aim of the study was to adapt and validate dietary and PA assessment tools for use among Nepalese pregnant women. With respect to PA, the study aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of a culturally adapted version of the 16-item GPAQ [10]. Because PA may vary dramatically during pregnancy due to physiological changes, we assessed its reliability at two-time points in the 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Accelerometer data from the 2nd trimester was used for validation as pregnant women are more likely to be active during this time [9].

To participate, women had to be 18 years or older, ≤14 weeks of gestation at enrollment, and carrying a single fetus. Additionally, to participate in the validation study with the accelerometer in the 2nd trimester, the participant had to agree to wear the accelerometer on their wrist for seven consecutive days; women with contraindications to exercise were not eligible for the validation study. At enrollment and subsequent ANC visits, a trained research assistant collected data from each participant via medical record review and patient interview. Data was collected on socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics. All participants provided written informed consent. The Kathmandu University Ethical Review Board (102/18) and the Rutgers Newark Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Pro2018001976) approved the study protocol.

GPAQ adaptation for the target population

The GPAQ includes 16 questions which gather information about SB as well as levels of PA across five settings. These include PA related to work/domestic/occupational tasks (vigorous and moderate), travel/transportation such as walking or biking, and leisure/recreational activities (vigorous and moderate) [9, 10, 14,15,16]. Vigorous activity is defined as an activity that causes large increases in breathing or heart rate while moderate activity causes small increases in heart rate.

For this study, a modified GPAQ was developed by translating the questionnaire into Nepali and creating a PA chart that included examples specific to the target demographic of Nepali pregnant women. For PA related to work/domestic tasks, examples for vigorous activity included construction work and carrying/stacking heavy loads (i.e., bricks), whereas examples for moderate activity included farm work, drawing water from well, and carrying light loads. For leisure/recreational PA, examples for vigorous activity included running and hiking/trekking, while examples for moderate activity included swimming or yoga. For each of the five PA domains (work-related vigorous, work-related moderate, travel, recreational vigorous, and recreational moderate), the GPAQ asks participants to report the time duration and frequency (number of days per week) of these activities during a typical week. To ascertain SB, participants are asked to report the amount of time they spent sitting per typical day (i.e., watching television/lounging on the couch/sitting at work). To adapt the questionnaire for use in pregnancy, we further specified the timeframe so that it refers to the PA during a typical week in the respective trimester (2nd or 3rd). The questionnaire was back translated in order to ensure fidelity between the English and Nepali versions. The Nepali version of the questionnaire was also cognitively tested among 8 pregnant volunteers to ensure its suitability in capturing the usual types and duration of physical activity among our target population.

GPAQ administration

To determine the trimester-specific reliability of the GPAQ, the questionnaire was administered to participants at two time-points, one month apart, in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Despite being administered a month apart, at both time points, the questions on the GPAQ were directed to ascertain PA and SB during a typical week in the respective trimester (2nd or 3rd trimester). Responses on the GPAQ were used to determine the duration of SB (min/day), as well as PA (minutes/week) for each of the five domains (work-related vigorous, work-related moderate, travel, recreational vigorous, and recreational moderate). Total moderate or vigorous PA (MVPA in min/week) was calculated by adding time spent in minutes/week across all five domains.

The GPAQ also allows for the computation of energy expenditure, recorded in metabolic equivalent tasks (METs). A standard value of 4 METs was assigned for moderate-intensity activities related to work/recreation/travel; 8 METs was assigned for work-or leisure-related vigorous activity [21]. According to the GPAQ responses with respect to duration, intensity, and frequency of activity, total MVPA was also calculated in MET-min/week. Total MVPA level was also classified as low, moderate, and high based on WHO guidelines (Fig. 1) [21].

Accelerometer

Data collected from the GPAQ was validated against PA data collected by a triaxial accelerometer (Axivity AX3; UK). The device captured activity based on changes in acceleration using a three-dimensional (3D) acceleration sensor, providing a more accurate and objective calculation of energy expenditure as compared to uniaxial devices and self-reported PA [22]. A subset of the subjects (n=34) who agreed to take part in the validation study wore the Axivity accelerometer on their left wrist for seven consecutive days during their 2nd trimester.

The accelerometer was set to record 3D acceleration data at a sample rate of 50Hz with a dynamic range of ±8g. The activity classification and non-wear time for each participant was extracted using the UK Biobank accelerometer analysis tool [23]. Non-wear time was defined as at least 60 consecutive minutes of stationary episodes with a standard deviation of less than 13.0mg and was imputed with data from similar time-of-day vector magnitude. For this analysis, MVPA was defined using a 100mg cut-off, as is done traditionally; and average daily time in MVPA (min/day) and SB (min/day) were calculated. All accelerometer data analysis was performed in Python. A minimum of 72 hours of continuous and valid wear time was necessary for inclusion in the analysis; 21 of 34 participants were included in the final analyses [23].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ±SD or median (25th-75th percentiles) for continuous variables, and frequencies (n, %) for categorical variables. The reliability of the GPAQ between the two visits within each trimester was tested by intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and Spearman's correlation coefficients (rho) for continuous variables including PA measures in each of the five domains (min/week), total MVPA (min/week), and SB (min/day). With respect to the level of PA (i.e. high, moderate, or low), the degree of consistency between the two GPAQ administrations in each trimester was evaluated using the Gwet's agreement coefficient (AC1). Gwet's AC1 was used because a skewed distribution was observed and the AC1 statistic overcomes the noted limitations of the kappa statistic and provides a more precise, stable agreement statistic [24]. For validation analyses comparing the average GPAQ measures in the 2nd trimester with those from the accelerometer, we used Spearman's correlation coefficients (rho) for continuous variables including total MVPA and SB.

ICC and Gwet's AC1 analyses were interpreted based the Cicchetti and Sparrow (1981) criteria [25]: <0.40 poor, 0.41-0.59 fair/moderate, 0.60-0.74 good and >0.75 excellent reliability. To interpret Spearman’s rho, the following criteria were used: 0-0.20 poor, 0.21-0.40 fair, 0.41-0.60 moderate/acceptable, 0.61-0.80 good, and 0.81-1.00 strong correlation [26].

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample are outlined in Table 1. Out of 101 participants enrolled at baseline, 90 and 83 participants completed both visits in the 2nd and 3rd trimester respectively. On average, the two visits in the 2nd trimester as well as the 3rd trimester were 4 weeks apart, and the mean difference in gestational age between 2nd trimester 1st visit and 3rd trimester 2nd visit was about 16 weeks. There were no significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between women who did and did not complete the follow-up visits in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. The primary reason for attrition was loss of contact (e.g., phone switched off, change in telephone number); only 2 had confirmed pregnancy loss.

Levels of PA as assessed by the GPAQ can be found in Table 2. None of the participants reported vigorous PA, either work-related or recreational, and only one participant reported moderate recreational PA. Almost all of the PA in the sample was attributed to moderate activity at home, work, or in travel-related tasks. Both work-related moderate PA and travel-related PA were higher in the 2nd trimester than the 3rd trimester; on average, total MVPA was higher by 50 min/week in the 2nd trimester. Mean reported time for SB declined by 27 min/week from the 2nd trimester to the 3rd trimester, yet the median values were consistent across four visits. Based on the WHO guidelines, almost all participants were classified as having low or moderate levels of PA, with the latter accounting for majority of the participants. The proportion of participants with moderate level of PA declined from the 2nd trimester to the 3rd trimester.

Reliability of the GPAQ

All PA scores across the 5 domains showed moderate to good reliability estimates in the 2nd and 3rd trimester (Table 2). In the 2nd trimester, the PA scores across 5 domains showed fair to moderate correlations (rhos ranging from 0.35 to 0.59), and moderate to good reliability with ICCs ranging from 0.45 to 0.67. In the 3rd trimester, the PA scores across 5 domains showed fair to good correlations (rhos ranging from 0.36 to 0.62), and moderate to good reliability (ICCs ranging from 0.48 to 0.69). Reliability for total MVPA was higher in the 3rd trimester compared to the 2nd trimester (ICCs 0.62 vs. 0.55), whereas the opposite was true for SB (ICCs 0.48 vs. 0.64). Consistency across the WHO classifications of low, moderate, and high level of PA, as measured using the AC1 statistic, was 0.614 (95% CI: 0.485, 0.744) in the 2nd trimester and 0.603 (95% CI: 0.469, 0.738) in the 3rd trimester, indicating good reliability. The percentage agreement across the 3 categories were 70% and 69.6% for the 2nd and 3rd trimester, respectively.

Validity of the GPAQ

GPAQ was validated against PA data collected by a 3D accelerometer worn by a subset of the subjects (n=21) for seven consecutive days in the 2nd trimester. Construct validity was assessed by comparing MVPA and SB, reported with the GPAQ and those derived from accelerometer counts, respectively (Table 3). The mean minutes of MVPA reported on GPAQ was similar to that measured by accelerometer (104.8 minutes on GPAQ vs. 112.5 minutes by accelerometer). The mean minutes of SB per day reported on GPAQ was 127.1 minutes, which was on average 330 minutes lower compared to that measured by the accelerometer. There was moderate correlation (rho = 0.42) between the GPAQ and accelerometer data for MVPA at 2nd trimester. However, there was only fair correlation (rho= 0.28) between SB assessed by the accelerometer and the GPAQ measure.

Discussion

This study examined the reliability and validity of a modified GPAQ that was adapted and translated for use among a sample of pregnant Nepalese women. The modified GPAQ appears to be a reliable and valid tool for assessing MVPA, but not SB, among pregnant women in Nepal. To our knowledge, this is the first PA assessment tool to be validated for use among pregnant women in Nepal.

Levels of PA among our sample were similar to those previously reported among samples of Asian women [27, 28]. A sample of pregnant women from Singapore (N=1171) reported an average of 1039.5 MET min/week between 26-28 gestation weeks, [27] while we reported 1142.3 min/week in the 2nd trimester and 959.8 min/week in the 3rd trimester. A relatively similar proportion of women were insufficiently active or had low activity (<600 MET min/week) in our sample (37.4%) compared to the sample in Singapore (34.1%) [27]. In another study with pregnant Taiwanese women, levels of household/occupational activity accounted for the highest percentage of PA performed across trimesters, [28] which is similar to our sample where almost all PA was attributed to moderate PA related to work/domestic tasks and travel. In addition, we observed an expected decline in all types of PA from early to late pregnancy, consistent with findings across populations of pregnant women from Asian [27] and non-Asian countries [29]. However, while prior studies also observed increases in SB across pregnancy, we found that the median SB levels remained consistent across four visits in pregnancy [27,28,29].

Our reliability and validity estimates were similar or slightly better than those reported among pregnant women in prior literature [11]. Of note, the validity of the GPAQ has only been explored among a single population of pregnant women in South Africa, where it was found to have poor agreement with accelerometry when measuring either PA or SB [19]. Specifically, Watson et al (2017) [19] found that the GPAQ had poor validity for total PA as well as SB, overestimating MVPA and underestimating SB when compared to accelerometer data [19]. The cultural and linguistic diversity of the South African study sample could have affected the internal validity of the study, and contributed to these negative findings. In our relatively homogeneous sample, the GPAQ underestimated SB but mean MVPA levels were similar across GPAQ and accelerometer measures. Among other studies utilizing the IPAQ and PPAQ there have been mixed results, with some finding acceptable validity and reliability and others finding reasonable reliability but poor validity, particularly for SB, and vigorous PA [9, 11, 30]. Harrison et al (2011) [9] found poor agreement between the IPAQ and the accelerometer data, with no significant correlation between the total, light, and moderate METminutes calculated using the accelerometer and those reported by the participants on the IPAQ (Harrison et al. 2011) [9]. Similar to Watson et al (2017)’s finding with GPAQ [19], Harrison et al (2011) [9] found that self-reported moderate METminutes were overestimated by the IPAQ when compared with the accelerometer; in contrast, the total METminutes and the light METminutes were underestimated [9]. Of note, this Australian study [9] consisted exclusively of women with overweight BMI status, who have been observed to over-report PA in some studies [37], which might explain the observed poor validity estimates. When adapting the PPAQ among a sample of pregnant women from China, Xiang et al (2016) [30] noted good reliability for total PA and sedentary, light, and moderate activity, but a lower reliability for vigorous activity [30]. In addition, the validity estimates were poor for both moderate and vigorous PA but were reasonable for light activity (r=0.33) and total PA (r=0.35) [30]. However, an important limitation of this study [30] was the use of uniaxial rather than triaxial accelerometry, which might have affected the validity estimates due to its limited measurement ability for certain PA activities (e.g., stationary exercises).

There are a few limitations to our study. Recall bias could have led to errors in self-report of PA behaviors, and we cannot rule out the potential for over or under estimation [31], though our shorter timeframe between GPAQ administrations is a desirable method to collect more accurate PA estimates from participants [9]. In addition, only a small subset of participants adhered to wearing the accelerometer for seven days. Compliance is a common concern among studies utilizing wearable accelerometer and mobile sensor technology [32]. While smartphones and their associated health applications are increasingly accessible, tracking PA via these devices is problematic as they may underestimate total steps and distance traveled when not routinely carried by the participant [33, 34]. In addition, while it is well-known that PA monitors are most accurate if placed on the hip, most wearable accelerometer devices are worn on the wrist and tend to misclassify non-ambulatory arm movements such as those completed in resistance or strength training exercises [32]. Still, accelerometers are notably more accurate than participant self-report even though few are thoroughly validated for these purposes [32]. With few women engaging in vigorous activity in our study, as in prior literature, [30, 35] we could not validate the GPAQ among our sample with respect to this type of exercise. Cultural attitudes surrounding exercise during pregnancy may explain why low levels of vigorous PA were observed among our sample [35]. Recommendation against vigorous activity during pregnancy is prevalent in Asian populations, as it is viewed as potentially causing stress and harm to the mother and developing baby [35]. Lastly, since this study was done in a small sample of women recruited from a single hospital in Nepal, our findings cannot be generalized with assurance to pregnant populations elsewhere.

Despite these limitations, there are several strengths to our study. Our study adhered to standardized WHO protocols in administering the GPAQ and was the first to establish the reliability and validity of the GPAQ in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters, which enhances our understanding regarding usability of this tool within the pregnant population. Our selection of the GPAQ was intentional, as it is a PA assessment tool that has been extensively applied within LMICs like Nepal [9, 15, 16, 36]. We validated data from the GPAQ against data collected by a 3D accelerometer, which is preferred over self-reporting of PA and uniaxial accelerometry as it provides a more accurate calculation of energy expenditure [22]. The GPAQ was interviewer-administered by the same trained staff throughout the study, enhancing the reliability of the data collected [31]. In addition, we adapted and translated the GPAQ to include culture-specific PA examples to improve the suitability of the questionnaire for our target population of pregnant Nepalese women.

Conclusion

In this study, the GPAQ showed acceptable reliability and validity when used to assess moderate PA among a sample of pregnant women in Nepal. However, we recommend the GPAQ be used with caution to assess SB among pregnant women.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- GPAQ:

-

Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

- ICC:

-

Intra class correlation

- rho:

-

Spearman's correlation coefficients

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent

- MVPA:

-

Moderate to vigorous physical activity

- SB:

-

Sedentary behavior

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62.

da Silva SG, Ricardo LI, Evenson KR, Hallal PC. Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Pregnancy and Maternal-Child Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Cohort Studies. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). Sports medicine. 2017;47:295–317.

Russo LM, Nobles C, Ertel KA, Chasan-Taber L, Whitcomb BW. Physical activity interventions in pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:576–82.

Perales M, Santos-Lozano A, Ruiz JR, Lucia A, Barakat R. Benefits of aerobic or resistance training during pregnancy on maternal health and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review. Early Hum Dev. 2016;94:43–8.

O’Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, et al. The ABC of Physical Activity for Health: a consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:573–91.

Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, Woll A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity – a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:813.

Rennie KL, Wareham NJ. The validation of physical activity instruments for measuring energy expenditure: problems and pitfalls. Public Health Nutr. 1998;1:265–71.

Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1750–60.

Harrison CL, Thompson RG, Teede HJ, Lombard CB. Measuring physical activity during pregnancy. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:19.

Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world health organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. 2006;14:66–70.

Sattler MC, Jaunig J, Watson ED, et al. Physical Activity Questionnaires for Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). Sports. 2018;48:2317–46.

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:790–804.

Keating XD, Zhou K, Liu X, et al. Reliability and Concurrent Validity of Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ): A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019;16(21):4128.

Armstrong T, Bauman A, Davies J. Physical activity patterns of Australian adults. Canberra: AIHW; 2000.

Hoos T, Espinoza N, Marshall S, Arredondo EM. Validity of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) in adult Latinas. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:698–705.

Cleland CL, Hunter RF, Kee F, Cupples ME, Sallis JF, Tully MA. Validity of the global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) in assessing levels and change in moderate-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1255.

Cramp AG, Bray SR. Postnatal women’s feeling state responses to exercise with and without baby. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:343–9.

Tendais I, Figueiredo B, Mota J, Conde A. Physical activity, health-related quality of life and depression during pregnancy. Cadernos de saude publica. 2011;27:219–28.

Watson ED, Micklesfield LK, van Poppel MNM, Norris SA, Sattler MC, Dietz P. Validity and responsiveness of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) in assessing physical activity during pregnancy. PloS one. 2017;12:e0177996.

Poudevigne MS, O’Connor PJ. A review of physical activity patterns in pregnant women and their relationship to psychological health. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). Sports. 2006;36:19–38.

World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide V2 [https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/GPAQ%20Instrument%20and%20Analysis%20Guide%20v2.pdf] Accessed 20 Jan 2022.

Fridolfsson J, Börjesson M, Buck C, et al. Effects of Frequency Filtering on Intensity and Noise in Accelerometer-Based Physical Activity Measurements. Sensors (Basel). 2019;19:2186.

Doherty A, Jackson D, Hammerla N, et al. Large Scale Population Assessment of Physical Activity Using Wrist Worn Accelerometers: The UK Biobank Study. PloS One. 2017;12:e0169649.

Gwet K. Inter-rater reliability: dependency on trait prevalence and marginal homogeneity. Stat Methods Inter-Rater Reliab Assess. 2002;2:1–9.

Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am J Ment Defic. 1981;86:127–37.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Padmapriya N, Shen L, Soh SE, et al. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Patterns Before and During Pregnancy in a Multi-ethnic Sample of Asian Women in Singapore. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:2523–35.

Lee CF, Hwang FM, Lin HM, Chi LK, Chien LY. The Physical Activity Patterns of Pregnant Taiwanese Women. J Nurs Res. 2016;24:291–9.

Newham JJ, Allan C, Leahy-Warren P, Carrick-Sen D, Alderdice F. Intentions Toward Physical Activity and Resting Behavior in Pregnant Women: Using the Theory of Planned Behavior Framework in a Cross-Sectional Study. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2016;43:49–57.

Xiang M, Konishi M, Hu H, et al. Reliability and Validity of a Chinese-Translated Version of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1940–7.

Metcalf KM, Baquero BI, Coronado Garcia ML, et al. Calibration of the global physical activity questionnaire to Accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary behavior. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:412.

Wright SP, Hall Brown TS, Collier SR, Sandberg K. How consumer physical activity monitors could transform human physiology research. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;312:R358–67.

Duncan MJ, Wunderlich K, Zhao Y, Faulkner G. Walk this way: validity evidence of iphone health application step count in laboratory and free-living conditions. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:1695–704.

Höchsmann C, Knaier R, Eymann J, Hintermann J, Infanger D, Schmidt-Trucksäss A. Validity of activity trackers, smartphones, and phone applications to measure steps in various walking conditions. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28:1818–27.

Han J-W, Kang J-S, Lee H. Validity and Reliability of the Korean Version of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5873.

Vaidya A, Krettek A. Physical activity level and its sociodemographic correlates in a peri-urban Nepalese population: a cross-sectional study from the Jhaukhel-Duwakot health demographic surveillance site. Int J Behav Nutr Physical Act. 2014;11:39.

Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(27):1893–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the Rutgers Global Health Institute & National Institutes of Health/FIC under Grant # NIH 1R21TW011377-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Noha Algallai and Shristi Rawal had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: S. Rawal; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: N. Algallai, K. Martin, and S. Rawal. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: N. Algallai, K. Shah, & S. Rawal. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was conducted in accord with prevailing ethical principles and was reviewed and approved by the Rutgers Newark Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Pro2018001976) and the Ethical Review Board of the Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences (102/18).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable- All data has been de-identified.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Algallai, N., Martin, K., Shah, K. et al. Reliability and validity of a Global Physical Activity Questionnaire adapted for use among pregnant women in Nepal. Arch Public Health 81, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01032-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01032-3