Abstract

In this paper, we propose a fractional form of a new three-dimensional generalized Hénon map and study the existence of chaos and its control. Using bifurcation diagrams, phase portraits and Lyapunov exponents, we show that the general behavior of the proposed fractional map depends on the fractional order. We also present two control schemes for the proposed map, one that adaptively stabilizes the fractional map, and another to achieve the synchronization of the proposed fractional map.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Discrete chaos has been of interest to researchers in science and engineering for decades [1]. Over the years, many chaotic and hyperchaotic maps have been proposed in the literature [2]. These maps quickly found applications in encryption and secure communications once their synchronization became possible [3]. For instance, the class of three-dimensional chaotic and hyperchaotic maps have been an interesting subject due to the fact that such maps exhibit a rich chaotic behavior as demonstrated in numerous studies [4].

For a long time, the study and application of fractional calculus were limited to continuous time [5,6,7,8,9]. Recently, researchers have diverted their attention to the discrete fractional calculus and attempted to put together a complete theoretical framework for the subject. The first definition of a fractional difference operator was made by Diaz and Olser in 1974 [10]. The interesting fact about this operator is that it is a generalization of the binomial formula for the nth difference operator by means of the Gamma function. In 1989, Miller and Ross defined the fractional order sum and difference operators [11]. Among the most interesting and relevant works on discrete fractional calculus in the last decade are references [12, 13]. In [14], the author discussed the discrete difference counterparts of conventional Riemann and Caputo derivatives. Furthermore, some advances have been made in fractional finite difference equations and fractional difference inclusions [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Recent studies have examined the stability conditions for fractional discrete-time systems, including [23]. Another interesting study is [24], where the authors established and proved a discrete fractional version of the well-known direct Lyapunov method. Some useful Lyapunov functions for Riemann–Liouville-like fractional difference equations can be looked up in [25]. More stability results can be found in [26, 27].

Since the topic of discrete fractional calculus is still new, very few fractional order chaotic maps have been proposed in the literature [28,29,30,31,32]. From what has been reported, fractional chaotic maps are sensitive to variations in the fractional order in addition to their natural sensitivity to variations in the initial conditions and parameters [33]. The few studies that exist in the literature in relation to fractional chaotic maps seem to agree that fractional chaotic maps exhibit richer dynamics compared to their integer counterparts [34]. This makes them more suitable to applications requiring a higher entropy such as the encryption of data and secure communications [35, 36]. To the best of our knowledge, the study of bifurcations, chaos and control for three-dimensional fractional maps remains to this day a new and mostly unexplored field [37]. This has motivated us to examine the phenomenon and develop suitable control laws for stabilization and synchronization.

In this paper, we are particularly interested in a new three-dimensional generalized Hénon map [38]. We aim to extend this map into the fractional case and investigate the resulting system’s dynamics. We look at the bifurcation graphs and give rough experimental bounds on the fractional order to separate between the asymptotically stable and chaotic ranges. The main motivation behind this work is a desire to assess the benefits of the fractional map. In this study, we are also interested in the control of this fractional map, including stabilization and synchronization schemes. From these results we find that the proposed three-dimensional fractional map has new interesting complex dynamical behaviors.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows. Some of the necessary notations and stability theory are introduced in Sect. 2. Section 3 presents the proposed fractional map and discusses its bifurcation plots and experimental bounds on the fractional order that guarantee a chaotic behavior. Section 4 proposes a one-dimensional control law for the stabilization of the proposed fractional map. In addition, Sect. 4 defines and proposes a control law for the synchronization scheme. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the main findings of the study and poses ideas for future work.

2 Basic concepts

In this section, we recall some of the necessary theory related to the subject of discrete-time fractional calculus and stability of fractional-order maps. Throughout our work, we will denote by \({}^{C}\Delta_{a}^{\upsilon}X ( t ) \) the υ-Caputo type delta difference of a function \(X ( t ):\mathbb{N} _{a}\rightarrow\mathbb{R} \) with \(\mathbb{N} _{a}= \{ a,a+1,a+2, \dots \} \) [14], which is of the form

for \(\upsilon\notin\mathbb{N} \) being the fractional order, \(t\in\mathbb{N} _{a+n-\upsilon}\), and \(n= \lceil\upsilon \rceil+1\). The υth fractional sum is defined as [12]

with \(t\in\mathbb{N} _{a+\upsilon}\), \(\upsilon>0\). The term \(t^{ ( \upsilon ) }\) denotes a decreasing function defined in terms of the Gamma function Γ as

The following theorems provide the basis for the numerical method and stability analysis that we will require later on in the paper when dealing with the proposed fractional-order discrete-time system.

Theorem 1

([13])

For the fractional difference equation

the equivalent discrete integral equation can be obtained as

where

Theorem 2

([39])

The zero equilibrium of the linear fractional-order discrete-time system

where \(X(t)= ( x_{1}(t),\dots,x_{n}(t) ) ^{T}\), \(0<\upsilon\leq1\), \(\mathbf{M}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times n}\) and \(\forall t\in\mathbb{N} _{a+1-\upsilon}\), is asymptotically stable if

for all the eigenvalues λ of M.

3 Dynamics of fractional-order generalized Hénon map

We consider the new 3D generalized Hénon map proposed in [40]. The so-called three-dimensional generalized Hénon map is of the form

where a and b are bifurcation parameters. This map exhibits chaos, for instance, when \(( a,b ) = ( 0.7281,0.5 ) \) and \(( x(0),y(0),z(0) ) = ( 1,0,0 ) \), as demonstrated by the phase portraits shown in Fig. 1. It is always helpful to examine the bifurcation diagram corresponding to a specific critical parameter in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of a chaotic system, see Fig. 2.

Chaotic attractors of the map (9) in: (a) x–y plane (b) x–z plane (c) x–y–z space

(a) Bifurcation diagram of the map (9); (b) largest Lyapunov exponent

The map (9) can be rewritten in the first difference order form given by

Introducing the Caputo-like delta difference defined in (1) leads to the fractional-order map

where \(t\in N_{a+1-\upsilon}\), \(0<\upsilon<1\) denotes the fractional order, and a is the starting point. The discrete integral formula described in Theorem 1, gives us the equivalent system

where \(t\in N_{a+1}\). Taking into account that \((t-s-1))^{( \upsilon-1)}=\frac{\varGamma(t-s)}{\varGamma(t-s-v+1)}\) is a discrete kernel function, and with starting point \(a=0\), we end up with the numerical formulas

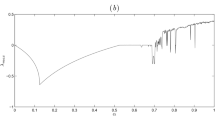

With the same initial conditions and the bifurcation parameter values adopted in Fig. 1 above, computer simulations were used to evaluate the numerical formulas (13) in order to gain a perspective on the dynamics of the fractional map (11). The bifurcation diagram and the corresponding largest Lyapunov exponent for \(\upsilon\in{}[ 0.96,1]\) are given in Fig. 3. We set \(n=700\) and we plot only the last 200 iterations. The largest Lyapunov exponent has been computed by using the Jacobian matrix algorithm proposed in [41]. Figures 3(a) and 3(b) visualize how the fractional order υ can make an effect on the system behavior. First, we note that when \(0\leq\upsilon\leq0.969\) the fractional map diverges to infinity. On the contrary, it can be observed that there are vertical lines with a positive largest Lyapunov exponent when \(\upsilon\in\mathopen{]}0.969,0.97[\). In this case, the solution \(x(n)\) converges to a chaotic attractor. From Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), we can see that there is transition from chaos to periodic cycles, followed by a series of appearance and disappearance of chaos, meaning that the largest Lyapunov exponent changes its values between negative and positive numbers as \(\upsilon\in [ 0.97,0.986 ] \). Finally, when \(\upsilon\in \mathopen{]} 0.986,1 ] \), the solution \(x(n)\) always settles into a strange attractor.

(a) Bifurcation of the fractional map (11) with fractional order υ; (b) largest Lyapunov exponent with fractional order υ

In what follows, we illustrate the bifurcation diagrams for \(a\in{}[0.3,0.8]\), see Fig. 4. To provide these diagrams, we set \(n=2000\) and fix \(b=0.5\). Then we discard away the first 1700 results, and the last 300 points are displayed in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), corresponding to fractional order values \(\upsilon=0.987\) and \(\upsilon=0.975\), respectively. As a passes to the interval \([0.66,0.7885]\), periodic cycles and chaotic regions are apparent. However, when the value of υ is set to 0.975, one can see the jumping behavior from a chaotic set to 3 periodic orbits that suddenly change into 3 small-sized attractors at \(a=0.326\). With the increase of parameter a, the fractional map goes directly to a fully developed chaotic regime. It is worth pointing out that the fractional map never produces the same largest Lyapunov exponent twice, we deduce that each value of υ has its own attractor.

In Fig. 5, an attractor which includes a periodic orbit is shown. Figures 6 and 7 show chaotic attractors of the fractional map corresponding to \(\upsilon=0.987\) and \(\upsilon=0.9695\), respectively. For completeness, Fig. 8 shows the states of the fractional map with 2000 iterations, \(( a,b ) = ( 0.7281,0.5 ) \), \(( x(0),y(0),z(0) ) = ( 1,0,0 ) \) and \(\upsilon=0.987\).

4 Control strategies

One of the important aspects in the study of chaotic systems is the development of control strategies to achieve stabilization. Another interesting aspect is the synchronization of one chaotic system to another. In this section, we introduce two control laws aimed at stabilizing and synchronizing the proposed fractional map.

4.1 Stabilization

The aim of stabilizing the proposed map is to devise an adaptive control law such that all of the system’s states are stabilized to 0. The following theorem presents our result.

Theorem 3

The fractional-order map (11) can be stabilized under the following one-dimensional control law:

Proof

The controlled fractional-order map (11) can be described as

Substituting the proposed control law (14) into (15) yields the simplified dynamics

The error system (16) can be written in a compact form as

where

Our aim is to show that the zero equilibrium of (17) is asymptotically stable, which means that the system states converge towards zero as time progresses. Asymptotic stability can be established using the linearization method as described in Theorem 2. Now it is easy to see that all the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\), \(\lambda_{2}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) of the matrix M satisfy

From Theorem 2, it is evident that the zero solution of (17) is asymptotically stable and, therefore, the fractional map (11) is stabilized. □

A numerical simulation was carried out to illustrate the result of Theorem 3. We chose the parameters \(( a,b ) = ( 0.7281,0.5 ) \), initial conditions \(( x(0),y(0),z(0) ) = ( 1,0,0 ) \), and fractional order \(\upsilon=0.98\). Assuming \(a=0\), the evolution of states towards zero is depicted in Fig. 9, which confirms the theoretical control proposed in Theorem 3.

The stabilized states and attractor of the fractional map (11)

4.2 Synchronization

Synchronization refers to the addition of a set of control parameters to the controlled chaotic system and adaptively updating the controls such that the states become synchronized. As for the drive system, we select the 3D fractional map proposed in [42]. The drive system is described as for \({ \small t\in\mathbb{N} }_{a+1-\upsilon}\) by

Subject to \(( \alpha,\text{ }\beta ) = ( 0.99,\text{ }0.2 ) \), \(a=0\) and \(\upsilon=0.984\), the fractional map (19) is chaotic as shown in Fig. 10. Note that the subscript m in the states refers to the drive system.

Chaotic behavior of the fractional map (19)

Similarly, the subscript s is used to denote the states of the response system. The response, thus, is given by

where the functions \(u_{i} ( t ) \) for \(i=1,2,3\), denote the synchronization controllers.

The error system corresponding to the synchronization strategy is defined as

To realize complete synchronization between the drive system (19) and response system (20), we discuss the asymptotical stability of zero solution of the error system given in (21). That is, we find the controllers \(u_{1} ( t )\), \(u_{2} ( t ) \) and \(u_{3} ( t ) \) such that the solution of the error system (21) go to 0 as t goes to +∞. The following theorem presents the proposed control law for this scheme of synchronization.

Theorem 4

Subject to

the drive system (19) and the response system (20) are synchronized.

Proof

The error system (21) has the fractional Caputo differences

Substituting the control law (22) into (23) yields the reduced dynamics

The eigenvalues of the linear part of the system (24) satisfy the stability conditions

By means of Theorem 2, we know that the zero solution of (24) is globally asymptotically stable and, consequently, the maps (19)–(20) are synchronized. □

The control laws stated in Theorem 4 are confirmed through numerical simulations. Figure 11 depicts the time evolution of states of the drive and the response systems (19)–(20) after control. The errors clearly converge towards zero, indicating that the described synchronization is successful.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we examined a new fractional-order discrete-time chaotic system. The proposed map is thought of as a fractional extension of a new 3D generalized Hénon map. Discrete fractional calculus was employed to analyze the dynamics of the new fractional map. We also proposed a stabilizing strategy for the proposed fractional map. The stabilization method is one-dimensional, meaning that we are only required to adaptively control one of the states in the system to guarantee convergence of all states towards zero. Moreover, we propose a synchronization scheme whereby the proposed fractional map is considered as a response and the drive is another 3D fractional map. Throughout the paper, numerical solutions were presented to confirm the findings and verify the feasibility of the proposed laws.

Our plan for future work includes an investigation of the applicability of the fractional chaotic map proposed in this paper in encryption and secure communication. We will consider different encryption algorithms and scenarios and will benchmark the results against well known integer-order maps.

References

Elaydi, S.N.: Discrete Chaos: With Applications in Science and Engineering. Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (2007)

Zhang, W.B.: Discrete Dynamical Systems, Bifurcations, and Chaos in Economics. Elsevier, Boston (2006)

Cruz-Hernandez, C., Lopez-Gutierrez, R.M., Aguilar-Bustos, A.Y., Posadas-Castillo, C.: Communicating encrypted information based on synchronized hyperchaotic maps. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 11(5), 337–349 (2010)

Jiang, H., Liu, Y., Wei, Z., Zhang, L.: A new class of three-dimensional maps with hidden chaotic dynamics. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos Appl. Sci. Eng. 26(12), 1650206 (2016)

Baleanu, D., Mousalou, A., Rezapour, S.: A new method for investigating approximate solutions of some fractional integro-differential equations involving the Caputo–Fabrizio derivativer. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 51 (2017)

Baleanu, D., Mousalou, A., Rezapour, S.: On the existence of solutions for some infinite coefficient-symmetric Caputo–Fabrizio fractional integro-differential equations. Bound. Value Probl. 2017, 145 (2017)

Baleanu, D., Rezapour, S., Mohammadi, H.: Some existence results on nonlinear fractional differential equations. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 371(1990), 20120144 (2013)

Kojabad, E.A., Rezapour, S.: Approximate solutions of a sum-type fractional integro-differential equation by using Chebyshev and Legendre polynomials. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 351 (2017)

Aydogan, S.M., Baleanu, D., Mousalou, A., Rezapour, S.: On approximate solutions for two higher-order Caputo–Fabrizio fractional integro-differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 221 (2017)

Diaz, J.B., Olser, T.J.: Differences of fractional order. Math. Comput. 28, 185–202 (2016)

Miller, K.S., Ross, B.: Fractional difference calculus. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Univalent Functions, Fractional Calculus and Their Applications, pp. 139–152 (1989)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: Discrete fractional calculus with the nabla operator. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. Spec. Ed. I 2009, 3 (2009)

Anastassiou, G.A.: Principles of delta fractional calculus on time scales and inequalities. Math. Comput. Model. 52, 556–566 (2010)

Abdeljawad, T.: On Riemann and Caputo fractional differences. Comput. Math. Appl. 62, 1602–1611 (2011)

Baleanu, D., Rezapour, S., Salehi, S.: A k-dimensional system of fractional finite difference equations. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, 312578 (2014)

Agarwal, R.P., Baleanu, D., Rezapour, S., Salehi, S.: The existence of solutions for some fractional finite difference equations via sum boundary conditions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2014, 282 (2014)

Baleanu, D., Rezapour, S., Salehi, S.: On some self-adjoint fractional finite difference equations. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. 19, 59–67 (2015)

Rezapour, S.H., Salehi, S.: On the existence of solution for a k-dimensional system of three points Nabla fractional finite difference equations. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 41(6), 143–1444 (2015)

Baleanu, D., Rezapour, S., Salehi, S.: A fractional finite difference inclusion. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. 20(5), 834–842 (2016)

Ghorbanian, V., Rezapour, S.: On a system of fractional finite difference inclusions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 325 (2017)

Ghorbanian, V., Rezapour, S.: A two-dimensional system of Delta–Nabla fractional difference inclusions. Novi Sad J. Math. 47(1), 143–163 (2017)

Ghorbanian, V., Rezapour, S., Salehi, S.: On the existence of solution for a sum fractional finite difference inclusion. In: Tas, K., Baleanu, D., Machado, J.A.T. (eds.) Mathematical Methods in Engineering, pp. 145–160. Springer, Germany (2018)

Abu-Saris, R., Al-Mdallal, Q.: On the asymptotic stability of linear system of fractional order difference equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 16, 613–629 (2013)

Baleanu, D., Wu, G., Bai, Y., Chen, F.: Stability analysis of Caputo-like discrete fractional systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 48, 520–530 (2017)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Luo, W.H.: Lyapunov functions for Riemann–Liouville-like fractional difference equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 314, 228–236 (2017)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Huang, L.L.: Novel Mittag-Leffler stability of linear fractional delay difference equations with impulse. Appl. Math. Lett. 82, 71–78 (2018)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D.: Stability analysis of impulsive fractional difference equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 21, 354–375 (2018)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D.: Discrete fractional logistic map and its chaos. Nonlinear Dyn. 75, 283–287 (2014)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Zeng, S.D.: Discrete chaos in fractional sine and standard maps. Phys. Lett. A 378, 484–487 (2014)

Khennaoui, A.A., Ouannas, A., Bendoukha, S., Wang, X., Pham, V.T.: On chaos in the fractional-order discrete-time unified system and its control synchronization. Entropy 20(7), 530 (2018)

Ouannas, A., Khennaoui, A.A., Bendoukha, S., Vo, T.P., Pham, V.T., Huynh, V.V.: The fractional form of the Tinkerbell map is chaotic. Appl. Sci. 8, 2640 (2018)

Khennaoui, A.A., Ouannas, A., Bendoukha, S., Grassi, G., Lozi, R.P., Pham, V.T.: On fractional-order discrete-time systems: Chaos, stabilization and synchronization. Chaos Solitons Fractals 119, 150–162 (2019)

Edelman, M.: Fractional maps as maps with power-law memory. In: Afraimovich, V., Luo, A.C.J., Fu, X. (eds.) Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity, pp. 79–120. Springer, New York (2014)

Edelman, M.: On stability of fixed points and chaos in fractional systems. Chaos 28, 023112 (2018)

Huang, L., Baleanu, D., Wu, G., Zeng, S.: A new application of the fractional logistic map. Rom. J. Phys. 61(7–8), 1172–1179 (2016)

Kassim, S., Hamiche, H., Djennoune, S., Bettayeb, M.: A novel secure image transmission scheme based on synchronization of fractional-order discrete-time hyperchaotic systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 88, 2473–2489 (2017)

Shukla, M., Sharma, B.: Investigation of chaos in fractional order generalized hyperchaotic Henon map. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 78, 265–273 (2017)

Zheng, J., Wang, Z., Li, Y., Wang, J.: Bifurcations and chaos in a three-dimensional generalized Henon map. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 185 (2018)

Cermak, J., Gyori, I., Nechvatal, L.: On explicit stability condition for a linear fractional difference system. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 18, 651–672 (2015)

Zheng, J., Wang, Z., Li, Y., Wang, J.: Bifurcations and chaos in a three-dimensional generalized Hénon map. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 185 (2018)

Wu, G., Baleanu, D.: Jacobian matrix algorithm for Lyapunov exponents of the discrete fractional maps. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 22, 95–100 (2015)

Shukla, M., Sharma, B.: Investigation of chaos in fractional order generalized hyperchaotic Henon map. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 78, 265–273 (2017)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Prof. Guan Rong Chen, Department of Electronic Engineering, City University of Hong Kong for suggesting many helpful references.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The author Xiong Wang was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61601306) and Shenzhen Overseas High Level Talent Peacock Project Fund (No. 20150215145C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJ, AO, AAK and XW suggested the model, helped in results’ interpretation and manuscript evaluation. AAK, GG and VTP helped to evaluate, revise and edit the manuscript. GG and VTP supervised the development of work. LJ, AO and XW drafted the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouini, L., Ouannas, A., Khennaoui, AA. et al. The fractional form of a new three-dimensional generalized Hénon map. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2064-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2064-x