Abstract

Volcanoes have dormancy periods that may last decades to centuries meaning that eruptions at volcanoes with no historical records of eruptions are common. Baseline monitoring to detect the early stages of reawakening is therefore important even in regions with little recent volcanic activity. Satellite techniques, such as InSAR, are ideally suited for routinely surveying large and inaccessible regions, but the large datasets typically require expert interpretation. Here we focus on Turkey where there are 10 Holocene volcanic systems, but no eruptions since 1855 and consequently little ground-based monitoring. We analyse data from the first five years of the European Space Agency Sentinel-1 mission which collects data over Turkey every 6 days on both ascending and descending passes. The high relief edifices of Turkey’s volcanoes cause two challenges: 1) snow cover during the winter months causes a loss of coherence and 2) topographically-correlated atmospheric artefacts could be misinterpreted as deformation. We propose mitigation strategies for both. The raw time series at Hasan Dag volcano shows uplift of ~ 10 cm between September 2017 and July 2018, but atmospheric corrections based on global weather models demonstrate that this is an artefact and reduce the scatter in the data to < 1 cm. We develop two image classification schemes for dealing with the large datasets: one is an easy to follow flowchart designed for non-specialist monitoring staff, and the other is an automated flagging system using a deep learning approach. We apply the deep learning scheme to a dataset of ~ 5000 images over the 10 Turkish volcanoes and find 4 possible signals, all of which are false positives. We conclude that there has been no cm-scale volcano deformation in Turkey in 2015–2020, but further analysis would be required to rule out slower rates of deformation (< 1 cm/yr). This study has demonstrated that InSAR techniques can be used for baseline monitoring in regions with few historical eruptions or little reported deformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many volcanoes have periods of dormancy of decades to centuries between eruptions and eruptions from volcanoes with little historical record of activity are highly problematic because the populations and emergency managers have no experience of volcanism. Recent examples include the eruptions of Chaitén (Chile) in 2008, Sinabung (Indonesia) in 2010 and Soufrière Hills (Montserrat) in 1995. The Global Volcanism Program currently list 10 volcanic systems in Turkey with activity in the Holocene (Table 1), including 3 with historically recorded eruptions (GVP 2013). However, there have been no eruptions since 1855 and consequently there has been little investment in ground-based monitoring systems despite their proximity to large population centres in central Anatolia. The United Nations Global Assessment of Risk ranked Turkey at 14th for overall volcanic threat out of 95 volcanically active countries based on its historical record of volcanic eruptions and large population exposure. Thus, baseline monitoring of Turkish volcanoes remains important, despite the lack of eruptions in the last century.

Satellite-based remote sensing is increasingly used as a global tool for monitoring volcanoes (Furtney et al. 2018; Anantrasirichai et al. 2018). Satellite systems are particularly suited to providing baseline information for large regions (e.g. Biggs et al. 2011; Pritchard and Simons 2004) or providing information during eruptions when ground-based equipment cannot be deployed or repaired (Biggs et al. 2010; Sigmundsson et al. 2010; Arnold et al. 2019). Satellite systems are often the only available source of monitoring data when 1) ground based access is limited, for example, in areas of conflict or remote regions, or 2) resources are limited, for example in developing countries, or 3) where there have been few historical eruptions and political awareness of volcanic risks is low. ESA’s Sentinel-1 mission freely distributes radar images over Turkey every six days and this could form the backbone of a baseline monitoring system for detecting deformation.

In this article, we report preliminary findings from the first five years of the Sentinel-1 mission, which have been automatically processed by the LiCSAR system (Morishita et al. 2020). In particular, we demonstrate that for the high relief edifices of Turkish volcanoes, it is necessary to account for the effects of atmospheric water vapour and seasonal snow cover when identifying and measuring deformation. Finally, we consider how the dataset could be used operationally and in real time and develop two strategies for dealing with the large volumes of data produced. First, we design an easy to follow image classification scheme designed for non-specialist monitoring staff, and second we apply an automated flagging system using a deep learning approach.

Background: volcanic activity in Turkey

According to the Global Volcanism Programme, there have been 37 eruptions recorded in Turkey during the last 10,000 years (GVP 2013) (Fig. 1). Three volcanoes have erupted historically (GVP 2013): Nemrut Dağı in 1441, 1597, 1692 and 1881 with recent activity characterised by the formation of lava domes, basaltic and rhyolitic lavas (Karakhanian et al. 2002; Ulusoy et al. 2019a; Aydar et al. 2003). A gas and ash eruption occurred at Tendürek Dağı in 1855 (Karakhanian et al. 2002) and a VEI 3 eruption occurred at Ağrı (also known as Ararat) in 1840, and an uncertain eruption in 1783. Turkey is also susceptible to volcanic hazards including ash and volcanogenic tsunamis from neighbouring countries with volcanoes (Greece, Syria, Iran, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia).

Location of volcanoes and major cities in Turkey. The 200 km buffer zone indicates areas in neighbouring countries that could potentially be affected by eruptions from Turkish volcanoes. 1. Kula Volcanic Field; 2. Gölcük; 3. Karapınar Volcanic Field; 4. Hasan Dağı; 5. Göllüdağ; 6. Acıgöl; 7. Erciyes Dağı; 8. Karacadağ; 9. Nemrut Dağı; 10. Süphan Dağı; 11. Girekol Tepe; 12. Tendürek Dağı; 13. Ağrı; 14. Kars Plateau

Geological studies suggest numerous Holocene eruptions have occurred in Turkey. In eastern Anatolia, tephras in Lake Van (Sumita and Schmincke 2013b; Sumita and Schmincke 2013a) together with historic events indicate 27 eruptions of Nemrut Dağı (GVP 2013), making this Turkey’s most frequently active volcano. In addition to the 1855 eruption of Tendürek Dağı, radiocarbon dating shows an eruption also occurred there in 550 BC at (GVP 2013). Ararat (Ağrı) has eruptions recorded at 2500–2400 BC and in the 3th–fourth century (Karakhanian et al. 2002). In central Anatolia, Acıgöl, near the city of Nevşehir, has six possible eruptions, most recently in Roman times. Both Erciyes Dağı, near the populous city of Kayseri, and Hasandağ have several possible Holocene eruptions (Atıcı et al. 2018; Sarıkaya et al. 2019; Schmitt et al. 2014) and potential further events are suggested by archaeological evidence and a widespread Holocene tephra that can be traced as far as Lebanon (Hamann et al., 2010). Kula volcanic field located in western Anatolia erupted during the Bronze Age (Ulusoy et al. 2019b).

The absence of eruptions for over a century could suggest the volcanic risk is not an issue in Turkey. However, the historic record includes at least one eruption in Turkey for each of the centuries between 1100 and 1900 AD, suggesting that the last 170 years of quiescence is unusually long. Combined with the rapid population growth since the last eruption in 1855, baseline monitoring is important for all Turkey’s volcanoes, despite the lack of recent activity.

By combining data from a range of satellites, it is possible to construct an archive dating back to the 1990’s and this provides the opportunity to conduct a 20 year baseline deformation survey identifying periods of unrest (e.g. Pritchard and Simons 2004; Reath et al. 2019b; Biggs et al. 2011). Surveys such as these have increased the number of volcanoes known to be deforming five-fold in the last 20 years (Biggs and Pritchard 2017). The global compilation of Furtney et al. (2018) reports 306 volcanoes with satellite-detections: 147 of deformation, 146 with thermal anomalies and 173 with SO2 degassing. However, in Turkey, there are no records of satellite-detected degassing or thermal anomalies, and only one example of deformation. At Tendürek, Bathke et al. (2015, 2013) report subsidence at a rate of 1 cm/yr attributed to contraction of a sill at a depth of 4.5 km below the summit causing ‘sliding trapdoor’ motion along the caldera ring faults.

Methods: satellite data and processing

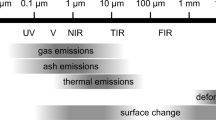

There are four types of satellite observations that are particularly relevant for volcano monitoring: 1) Deformation measurements made from radar imagery using a technique called Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) (e.g. Biggs et al. 2014; Pritchard et al. 2018; Richter and Froger 2020) 2) Measurements of active or passive degassing using either infrared or UV spectrometers (e.g. Carn et al. 2016); 3) Measurements of thermal anomalies associated with erupted material (e.g. Wright et al. 2004; Coppola et al. 2016) or fumarole activity (Reath et al. 2019a; Jay et al. 2013), 4) Mapping of volcanic products using visual observation of footprints, or topographic measurements for height changes (Poland 2014; Arnold et al. 2019; Meyer et al. 2015). Furtney et al. (2018) showed that satellite-based deformation measurements are dominantly pre-eruptive, while degassing and thermal measurements are dominantly co-eruptive. Since there have been no eruptions in Turkey during the satellite era, we focus on deformation measurements using InSAR.

The InSAR method measures the phase change between two Synthetic Aperture Radar images to produce maps known as interferograms. The phase change of the interferogram, ∆ϕi, is composed of several components, primarily deformation of the ground surface, ∆ϕdef, changes in the viewing geometry, ∆ϕgeom and delays associated with the radar path through the atmosphere, ∆ϕatm. The changes in viewing geometry can be corrected using accurate orbit information and a digital elevation model.

Here we use data from the Sentinel-1 constellation which carries C-band radar that operates in TOPSAR mode. Sentinel-1A was launched in 2014 and provides images over Turkey every 12 days. Since the launch of Sentinel-1B in 2017, the revisit time has reduced to 6 days. The data is freely available from the European Space Agency, automatically processed by the LiCSAR system described in Lazecky et al. (2020) and made available online at https://comet.nerc.ac.uk/COMET-LiCS-portal/. The Turkish Volcanoes can be covered using 7 frames of ascending data and 7 frames of descending data (Table 1). We use a least-squares approach to retrieve displacement maps at each date of acquisition (Schmidt and Burgmann 2003).

Despite the wealth of data, there are several challenges associated with using InSAR data for volcano monitoring. Atmospheric effects, primarily due to water vapour in the troposphere cause anomalies which can obscure deformation, or even lead to misinterpretation of the signals (Yip et al. 2019; Beauducel et al. 2000). These effects are particularly challenging at high relief, tropical volcanoes where the stratification of water vapour can lead to artefacts that correlate to topography (Ebmeier et al. 2013a; D'Oreye et al. 2008). Even though Turkey lies in an arid region, several of the volcanoes are very high relief and the stable continental climate may lead to persistent artefacts.

The second challenge is changes in the surface properties which leads to poor coherence between images. In tropical regions, poor coherence is typically caused by dense tropical vegetation, which scatters the C-band radar waves. The use of longer-wavelength radar systems which can penetrate vegetation, such as the ALOS L-band radar, has proved particularly successful under these circumstances (Ebmeier et al. 2013b; Chaussard and Amelung 2012; Fournier et al. 2010). In contrast, poor coherence in polar regions including Alaska and Iceland is typically caused by snow cover, leading some authors to concentrate on summer only acquisitions (e.g. Lu et al. 2010), or the regions surrounding ice caps (e.g. Sigmundsson et al. 2015). Turkey lies in an arid region, but the high volcanic peaks still experience snow fall during winter suggesting the processing strategy may need to be adapted to maintain coherence.

Results: use of InSAR at Turkish volcanoes

In this section, we discuss the suitability of InSAR for providing baseline monitoring for the volcanoes in Turkey, and consider appropriate strategies for data processing. We use Hasandağ in central Turkey as a test case, as it has good data availability but also high elevation (> 3200 m), meaning it is representative of the atmospheric artefacts and snow cover which may prove challenging for routine volcano monitoring using InSAR.

Coherence

Turkey is located in an arid environment and the region is not heavily vegetated, meaning the coherence is generally excellent and InSAR has been used for many tectonic studies (e.g. Cakir et al. 2005; Burgmann et al. 2002; Wright et al. 2001; Weiss 2020). However, the high peaks volcanic peaks are covered with snow during the winter months, reducing coherence.

Figure 2 shows example interferograms from Hasandağ. Figure 2a shows an interferogram constructed using acquisitions in May 2020 when there was no snow cover, whereas Fig. 2b is an interferogram constructed using acquisitions in January 2020, a time of year when snow cover is common. Coherence can be measured as the cross-correlation between the complex values in the SAR image with the theoretical range of values between 0 (no correlation) and 1 (perfect correlation). For the LICSAR processing, coherence thresholds are typically set at 0.15–0.2, with values > 0.5 common in urban and desert environments. Figure 2c shows the coherence image for the summer acquisitions, with values > 0.8, and the corresponding interferogram (Fig. 2a) shows continuous data coverage. In contrast the coherence image for the winter acquisitions (Fig. 2d) shows values < 0.1 over the volcanic edifice indicating snow cover on one or both acquisitions. The corresponding areas of the interferogram (Fig. 2b) have random phase values and cannot be used to infer anything about the surface deformation.

Example interferograms from Hasandağ showing seasonal effects on coherence a) interferogram showing good coherence in the snow-free summer months (6-18th May-2020) b) interferogram showing poor coherence when the peaks are covered in snow during the winter months (7–31 Jan 2020), c) coherence image corresponding to the interferogram shown in a). f) coherence image corresponding to the interferogram shown in b)

Figure 3 shows seasonal variation in coherence at Hasandağ. The mean and standard deviation of the coherence for 389 automatically-generated interferograms between October 2014 and May 2020 with time intervals of 12 and 24 days are plotted according to the date-of-year of the primary acquisition. The dataset contains 7 faulty interferograms which have coherence of 0 and can be easily discarded. A further 15 have average coherence values < 0.2 and these occur in the winter months and are associated with almost complete snow cover and cannot be used. Average values < 0.4 are relatively common and occur 103 times (27% of the dataset). In the winter months (Dec-Feb), these are attributed to partial snow cover over the high peaks, whereas in summer (Apr-Jul), it is due to vegetation growth and agriculture at lower elevations. However, not all the interferograms during these time periods are affected, so rather than skipping these periods entirely (e.g. Lu et al. 2010), it may be more appropriate to process interferograms all year round and discard those affected by poor coherence. In some cases, it may be necessary to process additional interferograms using snow-free acquisitions and longer time-spans to ensure that all time periods are covered. An alternative approach is to reprocess the dataset using a persistent scatterer method (e.g. Hooper et al. 2007; Ferretti et al. 2001), which has proven effective in semi-vegetated areas, but may not be appropriate when deep snow buries all infrastructure.

Identification of Atmospheric Artefacts

Atmospheric effects can be caused by variations in ionospheric or tropospheric properties. For C-band data at this latitude, tropospheric effects typically dominate (Liang et al. 2019) and are typically separated into a dry component associated with changes in pressure and temperature and a wet component associated with water vapour (Elliott et al. 2008; Jolivet et al. 2014; Doin et al. 2009). These can be further subdivided into short-wavelength ‘turbulent’ effects, and topographically-correlated effects associated with the stratification of atmospheric water vapour. At high-relief, conical volcanoes, these topographically-correlated delays cause patterns very similar to those expected from inflation or deflation of a magma reservoir (e.g. Ebmeier et al. 2013a; Beauducel et al. 2000).

Figure 4 shows examples of atmospheric artefacts from Hasandağ. The interferograms in Fig. 4a and b show a strong correlation with topography, with anomalies located over high topography. This can also be visualised by plotting the phase of each pixel in an individual interferogram against the topography of that pixel (e.g. Ebmeier et al. 2013a, Beauducel et al. 2000). Figure 4c and d show a spatially smooth pattern of noise, typical of transient water vapour features associated with turbulence in the troposphere and which tend to have wavelengths of < 10 km (e.g. Hanssen 2001; Emardson et al. 2003).

Example interferograms from Hasandağ showing common atmospheric artefacts a) 19-Aug-2015 to 30-Oct-2015 and b) 19-Nov-2018 to 1 Dec-2018 show stratified tropospheric artefacts that correlate to the steep topography of the volcanic edifice c) 6-Apr-2020 to 24-Apr-2020 and d) 14-Aug-2017 to 20-Aug-2017 show turbulent water vapour artefacts. All images are from ascending track 87

In previous studies, a pair-wise logic test has be useful in identifying acquisitions with particularly strong atmospheric artefacts (e.g. Massonnet and Feigl 1995; Ebmeier et al. 2013a). If the signal is associated with a strong atmospheric anomaly on a particular day the sign will change between successive interferograms. For example, we construct interferograms between images A, B and C when there is a strong atmospheric anomaly on acquisition date B. A negative anomaly appears on the volcanoes in interferogram B-A, whereas this anomaly appears positive in interferogram C-B. We expect both turbulent and stratified atmospheric anomalies to follow this pattern, but true deformation signals would reflect a permanent phase shift and the sign would not reverse in successive interferograms. However, we find that the pairwise logic approach performs poorly at identifying atmospheric artefacts in the data at Hasandağ. We attribute this to the stable continental climate where the atmospheric artefacts are low-level and persistent rather than extreme, infrequent events associated with, for example, the passage of a storm.

Correction of Atmospheric Artefacts

Several methods have been proposed to correct for atmospheric errors, and these can be divided into three categories: 1) empirical corrections based on the correlation between phase and topography (e.g. Bekaert et al. 2015; Beauducel et al. 2000), 2) corrections based on external datasets such as GPS or MERIS (e.g. Li et al. 2005; Li et al. 2009) and 3) corrections based on global or regional weather models (e.g. Yu et al. 2018; Jolivet et al. 2014; Parker et al. 2015; Doin et al. 2009). However, each of these has advantages and disadvantages when applied to individual volcanoes (e.g. Stephens et al. 2020), and the priority for volcano monitoring is confidently identifying which signals are atmospheric artefacts, and which are really deformation.

Here we follow the approach of Albino et al. (2020) and test two types of atmospheric corrections: 1) the phase elevation relationship and 2) GACOS corrections (Yu et al. 2018), which are based on the ECMWF High Resolution Weather Model (HRES- ECMWF). We find that while GACOS corrections work well on some example interferograms (Fig. 5a-c) and the phase-elevation corrections works well in others (Fig. 5d-f), neither method works well for every case. Having analysed a total of 288 interferograms, we find that the best approach to the entire dataset is to 1) apply the GACOS correction, 2) remove any long-wavelength ramps and 3) apply a phase-elevation correction. This gives a quality improvement, Q, of 22%, where Q is defined by the difference in standard deviation before and after correction, normalised by the standard deviation before correction (Albino et al. 2020).

Examples of atmospheric corrections to individual interferograms from track 167 which covers Hasandağ, Acıgöl-Nevsehir and Göllüdağ and encompasses elevations from 600 m–3600 m. a-c) example where b) the GACOS correction works better than c) the phase-elevation correction; d-f) example where e) the GACOS correction works worse than f) the phase-elevation correction

While these methods may be effective at reducing the effects of stratified water vapour fields and, in the case of weather models, long-wavelength atmospheric anomalies, they do not have the resolution to mitigate short-wavelength anomalies such as those associated with turbulence in the troposphere. However, since such anomalies are transient, we can assume that there is no correlation in time and they can be reduced stochastically. To illustrate, if we sum N independent interferograms of equal length, the signal will increase by a factor of N, whereas the noise will only increase by a factor of √N. The overall result is an increase in the signal to noise ratio by a factor of √N. In practice, interferograms are constructed using common acquisitions, meaning that the interferograms are not independent and chain stacking or time series approaches are more appropriate (Morishita et al. 2020; Berardino et al. 2002; Hooper et al. 2012).

Figure 6 shows the time series with and without atmospheric corrections for Hasandağ. The uncorrected time series has a seasonal component consistent with stratified atmospheric artefacts which could possibly show a possible uplift of ~ 10 cm starting in October 2017 (Fig. 6a). In comparison, the corrected time-series is much cleaner, and show no seasonal or other patterns (Fig. 6b). The standard deviation is reduced from 2.5 cm prior to correction to < 1 cm afterwards. We conclude that there is no volcanic deformation signal at Hasandağ during the period 2016–2018.

Discussion: towards operational monitoring

Many volcano observatories do not employ a specialist in InSAR data analysis, particularly in countries where there have been few historical eruptions and monitoring is conducted at a baseline level only. Lack of expertise is often cited as a barrier to the uptake of satellite technology and several capacity building efforts are ongoing to address this issue. An alternative is to develop automated systems that require little user input (Meyer et al. 2015; Lazecky et al. 2020). Here we consider two approaches that are particularly suited to regions with little record of volcano deformation who wish to use satellite data for baseline monitoring (i.e. flagging unusual activity) rather than modelling and forecasting deformation signals. In this case, our approach is based on image classification, either using a simplified scheme designed for non-specialists, or automated systems based on machine learning we then consider how the existing ground-based monitoring, (including the national seismic and GNSS networks) could be augmented if the satellite system were to detect unrest.

Guide to interpretation for non-specialists

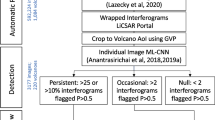

The aim of this section is to provide a simple and easy-to-follow classification scheme by which non-specialist monitoring staff can interpret images produced by automated systems such as LiCSAR. We adapt the flowchart of Ebmeier et al. (2013a) which was designed based on an L-band radar survey of Central America (Fig. 7). The flow chart includes decision points (shown as diamonds), causes of signals (white boxes), example data from Hasandağ, and mitigation strategies (pink boxes). In many cases, the mitigation strategies may be only be feasible retrospectively, or require specialist techniques, in which case, the images could be discarded from any real-time analysis.

Flowchart illustrating the process of analysing automatically generated interferograms, including checks and corrections for low coherence, topographic correlations and low signal-to-noise ratios before identifying possible signals. a-c Examples of common artefacts illustrated using examples from Hasandağ volcano, Turkey. a low coherence due to snow cover, b topographic correlation due to stratified water vapour and c low signal-to-noise ratio due to turbulent atmospheric effects

The first step is to identify whether the data is coherent. If the coherence over the summit is low, this suggests the interferogram is affected by snow fall on one or both of the acquisition dates, and needs to be discarded. If the time period covered is particularly critical, longer-duration interferograms which use different acquisitions dates may avoid the snow cover. The next step is to see whether the signal is correlated to topography, either by visual inspection, or by plotting the phase change against elevation. If there is a significant topographic dependence, the interferogram could be affected by a stratified atmospheric artefact, particularly if similar signals are seen over multiple peaks. Two mitigation strategies are available – either using an empirical correction based on the gradient of the phase elevation plot, or using a global weather model from an online service such as GACOS (http://ceg-research.ncl.ac.uk/v2/gacos/). The next stage is to consider the signal-to-noise ratio of the interferogram. In the case of slow deformation signals and short duration interferograms, turbulent atmospheric artefacts may obscure any real deformation. In this case, stacking or time-series approaches could be used retrospectively to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and lower the detection threshold. Having ruled out the other possibilities, any remaining signal is likely to be caused by real deformation. In this case, the data should be compared with any other available information (e.g. from the regional seismic network, other InSAR tracks or satellite systems) and modelled to identify the causative source.

Automatic detection using machine learning

Even with a simplified interpretation framework, the number of satellite images available poses a challenge for data management. The Sentinel-1 satellite has produced ~ 5000 images over the 10 Turkish volcanoes in the last 5 years, a rate of about 20 per week. Machine learning tools are increasingly important in handling such large datasets (Gaddes et al. 2019; Sun et al. 2020; Valade et al. 2019), and deep learning methods such as convolutional neural networks are especially useful for classifying images. Anantrasirichai et al. (2018, 2019a) developed a transfer learning approach to identifying volcano deformation in global datasets of Sentinel-1 imagery. The pre-trained network is re-trained using synthetic images to discriminate between real deformation and atmospheric artefacts. The best performing model considers just two classes: images composed of turbulent and stratified atmospheric components only (S + T) versus images containing deformation signals plus atmospheric artefacts (D + S + T). From a global dataset of > 30,000 images, Anantrasirichai et al. (2019a) identified just 52 positive results, of which 41 were true positives. While not perfect, this reduces the number of images requiring manual interpretation by two orders of magnitude, thus making routine analysis of large datasets tractable.

Here we apply that framework to the ~ 5000 images acquired over Turkish volcanoes in 2015–2020 (Table 2). The images have a range of timespans from 6 to 120 days, with a median value of 18 days. Since the algorithm is trained to distinguish between atmospheric artefacts and real deformation, we input the images prior to atmospheric correction. The algorithm identified just 4 positive results (Fig. 8, Table 2): two from Hasandağ in June 2015 and May–June 2019, one from Erciyes Dağı in October 2019 and one from Karacadağ in Feb-March 2019. Only one of these, the image from Erciyes Dağı had a probability > 0.9, while the images at Karacadağ and Hasandağ in 2019 only had very small areas with probabilities > 0.5 (Fig. 8). Since any real deformation would be expected to span multiple interferograms and these are all isolated images, these can be fairly simply assigned to the false positive category. The false positive rate of < 0.1% is consistent with the results of the global analysis (Anantrasirichai et al. 2019a), and dramatically reduces the need for manual inspection.

This shows that none of Turkey’s volcanoes are currently experiencing significant deformation. However, the detection threshold of the simple image-by-image approach is quite high as 3–4 cm in a 6 day interferogram corresponds to a rate of several meters per year. The detection limit can be reduced applying pre-processing techniques including time series analysis and overwrapping, giving a final detection threshold of < 1 cm/yr for a 5 year dataset (Anantrasirichai et al. 2019b). Similarly, the accuracy of the detection algorithm (number of false positive) can be improved by using global weather models to reduce the atmospheric artefacts (Anantrasirichai et al. 2019a).

Integration with other monitoring techniques

The ability of satellite systems to routinely survey large regions is invaluable for baseline monitoring, particularly for regions with few historical eruptions where investment may be limited. However, despite rapid technological development, satellite systems still cannot measure the range of phenomenon or achieve the same temporal and spatial resolution as ground-based sensors and are not expected to replace the need for ground-based networks (Ebmeier et al. 2018). When satellite (or other) systems detect unrest, additional monitoring may need to be deployed. Turkey has a well-developed regional GNSS network (e.g. Weiss 2020; Nocquet 2012), and the recent TurkVolc project set up campaign GNSS sites at Hasandağ and Erciyes Dag which could be rapidly upgraded to continuous sites if unrest were detected. Similarly, Turkey has a well-established seismic network designed for monitoring earthquake activity, with stations within 55 km of each of the volcanoes, and 8 volcanoes with stations within 20 km (Atici et al., pers. comm.). Recently, these have been supplemented by seismometers specifically designed to monitor volcano seismicity at Erciyes Dağı and Nemrut Dağı. Together these systems provide baseline monitoring, which could be rapidly augmented and densified if unrest were detected.

Conclusions

We conclude that the Sentinel-1 InSAR dataset has the potential to be used for baseline monitoring of Turkish volcanoes. The satellites acquire radar images every 6 days on both ascending and descending passes and the raw data is downloadable in near real time from the Copernicus Open Access Hub (https://scihub.copernicus.eu/) and processed products from the LiCSAR processing system (https://comet.nerc.ac.uk/comet-lics-portal/).

Our analysis of the first 5 years of Sentinel-1 data (2014–2020) has identified two primary challenges for the use of InSAR data for baseline monitoring of the high elevation Turkish volcanoes 1) seasonal snow cover over the high peaks which reduces interferometric coherence and 2) topographically-corrected artefacts associated with stratified tropospheric water vapour which can be misinterpreted as volcano deformation. We propose mitigation strategies for these issues including adaptation to the processing scheme, the use of atmospheric corrections based on global weather models and multi-interferogram approaches such as time series and stacking. We apply these to a retrospective analysis of 3 years of data from Hasandağ volcano and find the uncorrected time series shows a seasonal pattern with up to 10 cm of apparent uplift. In contrast, the corrected time series shows no systematic deformation and variations with a standard deviation of < 1 cm.

Since these approaches may not be feasible in real-time, we demonstrate two possible approaches for operation monitoring based on classification of individual images, either by non-specialist monitoring staff, or by deep learning algorithms. At present, the detection threshold of these methods is quite high, particularly for short-duration interferograms, but the field of machine learning is developing rapidly and techniques to improve the detection accuracy and threshold are likely to be available soon.

In conclusion, our analysis of the first 5 years of data from the Sentinel-1 mission finds no cm-scale deformation at any of the Turkish volcanoes, and we propose processing and analysis strategies adapted for using InSAR data for baseline volcano monitoring in Turkey.

Availability of data and materials

All raw satellite data are available from the Copernicus Open Access hub (https://scihub.copernicus.eu/) and processed products from the LiCSAR processing system (https://comet.nerc.ac.uk/comet-lics-portal/

References

Albino F, Biggs J, Yu C, Li Z (2020) Automated Methods for Detecting Volcanic Deformation Using Sentinel-1 InSAR Time Series Illustrated by the 2017–2018 Unrest at Agung, Indonesia. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 125:e2019JB017908

Anantrasirichai N, Biggs J, Albino F, Bull D (2019a) A deep learning approach to detecting volcano deformation from satellite imagery using synthetic datasets. Remote Sens Environ 230:111179

Anantrasirichai N, Biggs J, Albino F, Bull D (2019b) The application of convolutional neural networks to detect slow, sustained deformation in InSAR time series. Geophys Res Lett 46:11850–11858

Anantrasirichai N, Biggs J, Albino F, Hill P, Bull D (2018) Application of machine learning to classification of volcanic deformation in routinely generated InSAR data. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 123:6592–6606

Arnold DW, Biggs J, Dietterich HR, Vargas SV, Wadge G, Mothes P (2019) Lava flow morphology at an erupting andesitic stratovolcano: a satellite perspective on El Reventador, Ecuador. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 372:34–47

Atıcı, G., Friedrichs, B., Schmitt, A. K., Danisik, M., Yurteri, E., Gündoğdu, E. A. & Şen, E., Abstracts Volume of the International meeting “Cities on Volcanoes 10”, p879, 2–7 September 2018, Napoli, Italy 2018. Recent eruptive history of Mount Hasan and Mount Erciyes stratovolcanoes, Central Anatolia. Abstracts Volume of the International meeting “Cities on Volcanoes 10” 2–7 September 2018, Napoli, Italy

Aydar E, Gourgaud A, Ulusoy I, Digonnet F, Labazuy P, Sen E, Bayhan H, Kurttas T, Tolluoglu AU (2003) Morphological analysis of active mount Nemrut stratovolcano, eastern Turkey: evidences and possible impact areas of future eruption. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 123:301–312

Bathke H, Nikkhoo M, Holohan E, Walter T (2015) Insights into the 3D architecture of an active caldera ring-fault at Tendürek volcano through modeling of geodetic data. Earth Planet Sci Lett 422:157–168

Bathke H, Sudhaus H, Holohan E, Walter TR, Shirzaei M (2013) An active ring fault detected at Tendürek volcano by using InSAR. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 118:4488–4502

Beauducel F, Briole P, Froger JL (2000) Volcano-wide fringes in ERS synthetic aperture radar interferograms of Etna (1992–1998): deformation or tropospheric effect? J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 105:16391–16402

Bekaert D, Walters R, Wright T, Hooper A, Parker D (2015) Statistical comparison of InSAR tropospheric correction techniques. Remote Sens Environ 170:40–47

Berardino P, Fornaro G, Lanari R, Sansosti E (2002) A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR Interferograms. IEEE 40:2375–2383

Biggs J, Bastow ID, Keir D, Lewi E (2011) Pulses of deformation reveal frequently recurring shallow magmatic activity beneath the Main Ethiopian rift. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 12:Q0AB10

Biggs J, Ebmeier S, Aspinall W, Lu Z, Pritchard M, Sparks R, Mather T (2014) Global link between deformation and volcanic eruption quantified by satellite imagery. Nat Commun 5:3471

Biggs J, Mothes P, Ruiz M, Amelung F, Dixon T, Baker S, Hong S (2010) Stratovolcano growth by co-eruptive intrusion: the 2008 eruption of Tungurahua Ecuador. Geophys Res Lett 37:L21302

Biggs J, Pritchard ME (2017) Global volcano monitoring: what does it mean when volcanoes deform? Elements 13:17–22

Burgmann R, Ayhan ME, Fielding EJ, Wright TJ, McClusky S, Aktug B, Demir C, Lenk O, Turkezer A (2002) Deformation during the 12 November 1999 Duzce, Turkey, earthquake, from GPS and InSAR data. Bull Seismol Soc Am 92:161–171

Cakir Z, Akoglu AM, Belabbes S, Ergintav S, Meghraoui M (2005) Creeping along the Izmetpasa section of the North Anatolian fault (Western Turkey): rate and extent from InSAR. EPSL 238:225–234

Carn S, Clarisse L, Prata AJ (2016) Multi-decadal satellite measurements of global volcanic degassing. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 311:99–134

Chaussard E, Amelung F (2012) Precursory inflation of shallow magma reservoirs at West Sunda volcanoes detected by InSAR. Geophys Res Lett 39:L21311

Coppola D, Laiolo M, Cigolini C (2016) Fifteen years of thermal activity at Vanuatu's volcanoes (2000–2015) revealed by MIROVA. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 322:6–19

Doin M-P, Lasserre C, Peltzer G, Cavalié O, Doubre C (2009) Corrections of stratified tropospheric delays in SAR interferometry: validation with global atmospheric models. J Appl Geophys 69:35–50

D'Oreye, N., Fernandez, J., Gonzalez, P., Kervyn, F., Wauthier, C., Frischknecht, C., Calais, E., Heleno, S., Cayol, V., Oyen, A. & Marinkovic, P. Systematic InSAR monitoring of African active volcanic zones: What we have learned in three years, or an harvest beyond our expectations. Use of Remote Sensing Techniques for Monitoring Volcanoes and Seismogenic Areas, 2008. USEReST 2008. Second Workshop on, nov. 2008. [Formatter not found: ResolvePDF], 1–6

Ebmeier S, Andrews B, Araya M, Arnold D, Biggs J, Cooper C, Cottrell E, Furtney M, Hickey J, Jay J (2018) Synthesis of global satellite observations of magmatic and volcanic deformation: implications for volcano monitoring & the lateral extent of magmatic domains. J Appl Volcanol 7:2

Ebmeier S, Biggs J, Mather T, Amelung F (2013a) Applicability of InSAR to tropical volcanoes: insights from Central America. Geol Soc Lond, Spec Publ 380:15–37

Ebmeier SK, Biggs J, Mather TA, Amelung F (2013b) On the lack of InSAR observations of magmatic deformation at central American volcanoes. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 118:2571–2585

Elliott J, Biggs J, Parsons B, Wright T (2008) InSAR slip rate determination on the Altyn Tagh Fault, northern Tibet, in the presence of topographically correlated atmospheric delays. Geophysical Res Lett 35:L12309

Emardson T, Simons M, Webb F (2003) Neutral atmospheric delay in interferometric synthetic aperture radar applications: statistical description and mitigation. JGR 108. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JB001781

Ferretti A, Prati C, Rocca F (2001) Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. JGR 29. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5438.272

Fournier TJ, Pritchard ME, Riddick SN (2010) Duration, magnitude, and frequency of subaerial volcano deformation events: new results from Latin America using InSAR and a global synthesis. GCUBED 11:Q01003

Furtney MA, Pritchard ME, Biggs J, Carn SA, Ebmeier SK, Jay JA, Kilbride BTM, Reath KA (2018) Synthesizing multi-sensor, multi-satellite, multi-decadal datasets for global volcano monitoring. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 365:38–56

Gaddes M, Hooper A, Bagnardi M (2019) Using machine learning to automatically detect volcanic unrest in a time series of interferograms. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 124:12304–12322

GVP 2013. Global Volcanism Program (2013) Volcanoes of the World, v. 4.5. 2. Smithson. Institution, Natl. Museum Nat. Hist. https://volcano.si.edu/gvp_cite.cfm

Hamann Y, Wulf S, Ersoy O, Ehrmann W, Aydar, E, Schmiedl G (2010). First evidence of a distal early Holocene ash layer in Eastern Mediterranean deep-sea sediments derived from the Anatolian volcanic province. Quaternary Research 73(3):497–506

Hanssen RF (2001) Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Analysis. Kluwer Acad, Norwell, Mass.

Hooper A, Bekaert D, Spaans K, Arıkan M (2012) Recent advances in SAR interferometry time series analysis for measuring crustal deformation. Tectonophysics 514:1–13

Hooper A, Segall P, Zebker H (2007) Persistent scatterer interferometric synthetic aperture radar for crustal deformation analysis, with application to Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 112:B07407

Jay J, Welch M, Pritchard M, Mares P, Mnich M, Melkonian A, Aguilera F, Naranjo J, Sunagua M, Clavero J (2013) Volcanic hotspots of the central and southern Andes as seen from space by ASTER and MODVOLC between the years 2000 and 2010. Geol Soc Lond, Spec Publ 380:161–185

Jolivet R, Agram PS, Lin NY, Simons M, Doin MP, Peltzer G, Li Z (2014) Improving InSAR geodesy using global atmospheric models. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 119:2324–2341

Karakhanian A, Djrbashian R, Trifonov V, Philip H, Arakelian S, Avagian A (2002) Holocene-historical volcanism and active faults as natural risk factors for Armenia and adjacent countries. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 113:319–344

Lazecky M, Spaans K, González PJ, Maghsoudi Y, Morishita Y, Albino F, Elliott J, Greenall N, Hatton E, Hooper A, Juncu D, McDougall A, Walters RJ, Watson CS, Weiss JR, Wright TJ (2020) LiCSAR: an automatic InSAR tool for measuring and monitoring tectonic and volcanic activity. Remote Sens 12:2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs1215243

Li Z, Fielding E, Cross P, Preusker R (2009) Advanced InSAR atmospheric correction: MERIS/MODIS combination and stacked water vapour models. Int J Remote Sens 30:3343–3363

Li Z, Muller J-P, Cross P, Fielding EJ (2005) Interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) atmospheric correction: GPS, moderate resolution imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), and InSAR integration. J Geophys Res 110:B03410

Liang C, Agram P, Simons M, Fielding EJ (2019) Ionospheric correction of Insar time series analysis of c-band sentinel-1 tops data. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 57:6755–6773

Lu Z, Dzurisin D, Biggs J, Wicks C, McNutt S (2010) Ground surface deformation patterns, magma supply, and magma storage at Okmok volcano, Alaska, from InSAR analysis: I. Inter-eruption deformation, 1997-2008. JGR 115:B00B02

Massonnet D, Feigl KL (1995) Discrimination of geophysical phenomena in satellite radar interferograms. Geophys Res Lett 22:1537–1540

Meyer F, McAlpin D, Gong W, Ajadi O, Arko S, Webley P, Dehn J (2015) Integrating SAR and derived products into operational volcano monitoring and decision support systems. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens 100:106–117

Morishita Y, Lazecky M, Wright TJ, Weiss JR, Elliott JR, Hooper A (2020) LiCSBAS: an open-source InSAR time series analysis package integrated with the LiCSAR automated Sentinel-1 InSAR processor. Remote Sens 12:424

Nocquet J-M (2012) Present-day kinematics of the Mediterranean: a comprehensive overview of GPS results. Tectonophysics 579:220–242

Parker AL, Biggs J, Walters RJ, Ebmeier SK, Wright TJ, Teanby NA, Lu Z (2015) Systematic assessment of atmospheric uncertainties for InSAR data at volcanic arcs using large-scale atmospheric models: application to the Cascade volcanoes, United States. Remote Sens Environ 170:102–114

Poland MP (2014) Time-averaged discharge rate of subaerial lava at Kīlauea volcano, Hawai ‘i, measured from TanDEM-X interferometry: implications for magma supply and storage during 2011–2013. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 119:5464–5481

Pritchard M, Biggs J, Wauthier C, Sansosti E, Arnold D, Delgado F, Ebmeier S, Henderson S, Stephens K, Cooper C (2018) Towards coordinated regional multi-satellite InSAR volcano observations: results from the Latin America pilot project. J Appl Volcanol 7:5

Pritchard ME, Simons M (2004) An InSAR-based survey of volcanic deformation in the Central Andes. GCUBED 5:2002

Reath K, Pritchard M, Moruzzi S, Alcott A, Coppola D, Pieri D (2019a) The AVTOD (ASTER volcanic thermal output database) Latin America archive. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 376:62–74

Reath K, Pritchard M, Poland M, Delgado F, Carn S, Coppola D, Andrews B, Ebmeier S, Rumpf E, Henderson S (2019b) Thermal, deformation, and degassing remote sensing time series (CE 2000–2017) at the 47 most active volcanoes in Latin America: implications for volcanic systems. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 124:195–218

Richter N, Froger J-L (2020) The role of Interferometric synthetic aperture radar in detecting, mapping, monitoring, and Modelling the volcanic activity of piton de la Fournaise, La Réunion: a review. Remote Sens 12:1019

Sarıkaya MA, Çiner A, Zreda M, Şen E, Ersoy O (2019) Chlorine degassing constrained by cosmogenic 36Cl and radiocarbon dating of early Holocene rhyodacitic lava domes on Erciyes stratovolcano, Central Turkey. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 369:263–275

Schmidt DA, Burgmann R (2003) Time-dependent land uplift and subsidence in the Santa Clara valley, California, from a large interferometric, synthetic aperture radar dataset. JGR 108:8534–8543

Schmitt AK, Danišík M, Aydar E, Şen E, Ulusoy İ, Lovera OM (2014) Identifying the volcanic eruption depicted in a neolithic painting at Çatalhöyük, Central Anatolia, Turkey. PLoS One 9:e84711

Sigmundsson F, Hooper A, Hreinsdóttir S, Vogfjörd KS, Ófeigsson BG, Heimisson ER, Dumont S, Parks M, Spaans K, Gudmundsson GB (2015) Segmented lateral dyke growth in a rifting event at Bar [eth] arbunga volcanic system, Iceland. Nature 517(7533):191–195

Sigmundsson F, Hreinsdóttir S, Hooper A, Arnadóttir T, Pedersen R, Roberts MJ, Óskarsson N, Auriac A, Decriem J, Einarsson P, Geirsson H (2010) Intrusion triggering of the 2010 Eyjafjallajokull explosive eruption. Nature 468:426–430

Stephens KJ, Wauthier C, Bussard RC, Higgins M, LaFemina PC (2020) Assessment of mitigation strategies for tropospheric phase contributions to InSAR time-series datasets over two Nicaraguan volcanoes. Remote Sens 12:782

Sumita M, Schmincke H-U (2013a) Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van I: evolution of explosive volcanism of Nemrut volcano (eastern Anatolia) during the past> 400,000 years. Bull Volcanol 75:714

Sumita M, Schmincke H-U (2013b) Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van II: temporal evolution of explosive volcanism of Nemrut volcano (eastern Anatolia) during the past ca. 0.4 ma. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 253:15–34

Sun J, Wauthier C, Stephens K, Gervais M, Cervone G, La Femina P, Higgins M (2020) Automatic detection of volcanic surface deformation using deep learning. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 125:e2020JB019840

Ulusoy I, Çubukçu HE, Mouralis D, Aydar E (2019a) Nemrut caldera and eastern Anatolian volcanoes: fire in the highlands. Landscapes and Landforms of Turkey. World Geomorphological Landscapes. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03515-0_35

Ulusoy İ, Sarıkaya MA, Schmitt AK, Şen E, Danišík M, Gümüş E (2019b) Volcanic eruption eye-witnessed and recorded by prehistoric humans. Quat Sci Rev 212:187–198

Valade S, Ley A, Massimetti F, D’Hondt O, Laiolo M, Coppola D, Loibl D, Hellwich O, Walter TR (2019) Towards global volcano monitoring using multisensor sentinel missions and artificial intelligence: the mounts monitoring system. Remote Sens 11:1528

Weiss J (2020) High-resolution surface velocities and strain for Anatolia from Sentinel-1 InSAR and GNSS data

Wright R, Flynn LP, Garbeil H, Harris AJ, Pilger E (2004) MODVOLC: near-real-time thermal monitoring of global volcanism. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 135:29–49

Wright TJ, Parsons BE, Fielding EJ (2001) Measurement of interseismic strain accumulation across the North Anatolian Fault by satellite radar interferometry. GRL 28(6):2117–2120

Yip STH, Biggs J, Albino F (2019) Reevaluating volcanic deformation using atmospheric corrections: implications for the magmatic system of Agung volcano, Indonesia. Geophys Res Lett 46:13704–13711

Yu C, Li Z, Penna NT, Crippa P (2018) Generic atmospheric correction model for Interferometric synthetic aperture radar observations. J Geophysical Res Solid Earth 123:9202–9222

Acknowledgements

We thank Steve Sparks for his leadership of the TurkVolc project and helpful comments. We also thank the reviewers and editors for their constructive comments which have improved the manuscript.

Funding

SB, GA, AD and JB were supported by the Newton Fund TurkVolc project, NE/P008437/1 and TUBİTAK project, 116Y480. JB, FA, NA and SY were supported by the COMET, the NERC Centre for the Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics, a partnership between UK Universities and the British Geological Survey. NA, FA and JB were also supported by NERC Innovation Grant NE/S013970/1 ‘Making Satellite Volcano Deformation Analysis Accessible’. FD was supported by Council of Higher Education, Abroad Research Scholarship for Research Assistants. SY was supported by an EPSRC Impact Accelerator Internship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB conceived, wrote and co-ordinated the manuscript. FD and FA processed the Sentinel-1 data and analysed the atmospheric artefacts; SY analysed the interferometric coherence. AD, JB and FA participated in an exchange visit which developed the 'guide to interpretation for non-specialists' and SB and GA provided background information and context on the volcanic hazards in Turkey. NA worked on the machine learning. The authors all read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Biggs, J., Dogru, F., Dagliyar, A. et al. Baseline monitoring of volcanic regions with little recent activity: application of Sentinel-1 InSAR to Turkish volcanoes. J Appl. Volcanol. 10, 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-021-00102-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-021-00102-x