Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate whether oral administration of Lactobacillus brevis 23017 (LB) alone and in combination with ellagic acid inhibits ChTLR15/ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to attenuate intestinal inflammatory injury. Two animal experiments were performed. In Experiment 1, chickens were allocated into 7 groups: PBS, and low, medium and high dosages of live and heat-killed LB, named L/LB(+), M/LB(+) and H/LB(+), and L/LB(−), M/LB(−) and H/LB(−), respectively. In Experiment 2, chickens were divided into 5 groups: PBS, challenge control, and low, medium and high dosages of ellagic acid combined with LB(+), named L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+) and H/EA + H/LB(+), respectively. Chickens were gavaged with LB with or without ellagic acid once a day. Then, the mRNA and protein levels of the components of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway found in the caecal tissues were quantified. On Day 7 post-infection with E. tenella, the levels of the components of the ChTLR15/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway in the caeca were again quantified, and the anticoccidial effects were assessed. The results showed that the levels of the genes in the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in the chickens in the LB(+) groups were higher than those in the LB(−) groups (p < 0.001); those in the H/LB(+) group were higher than those in the M/LB(+) and L/LB(+) groups (p < 0.001); and those in the H/EA + H/LB(+) group showed the highest expression levels compared with the other groups (p < 0.001). After challenge, the chickens in the H/LB(+) group displayed less inflammatory injury than those in the M/LB(+) and L/LB(+) groups (p < 0.05), and the chickens in the H/EA + H/LB(+) group showed stronger anti-inflammatory effects than the other groups (p < 0.05). Thus, these protective effects against infection were consistent with the above results. Overall, significant anti-inflammatory effects were observed in chickens orally gavaged with high dosages of live L. brevis 23017 and ellagic acid, which occurred by regulation of the ChTLR15/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Avian coccidiosis is an intestinal protozoan disease caused by at least seven Eimeria species. Chickens infected by E. tenella, the most pathogenic Eimeria parasite, showed severe clinical symptoms, including bloody diarrhoea and dehydration. Infection with Eimeria leads to a decline in feed utilization efficiency and body weight gain, therefore ultimately causing serious economic losses to the commercial poultry industry. Previous studies have focused on preventing coccidiosis from the view of preventive immunity using attenuated live vaccines [1] and on interfering with parasite development through the use of anticoccidial drugs [2]. Recently, studies on novel anticoccidial products have become a research hotspot, aiming to overcome the drawbacks of traditional drugs and live vaccines, such as the emergence of drug-resistant parasites and virulence reversion of live vaccines.

The life cycle of Eimeria parasites is complex and consists of sexual and asexual stages. The immune responses and detailed mechanisms stimulated by Eimeria in different stages has not been very clear until now. It has been reported that the elicited innate immune responses during infection with the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii display a close relationship with inflammatory injury [3]. Our previous study showed that the inflammatory pathways of chicken NOD-like receptor 3 (ChNLRP3) and chicken interleukin 1 beta (ChIL-1β) are strictly related to the activation of chicken Toll-like receptor 15 (ChTLR15), chicken myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (ChMyD88) and the chicken nuclear transcription factor-κB (ChNF-κB) pathway, which is specifically activated by E. tenella sporozoites [4]. The previous results suggested that drugs or biological products with the capability to inhibit the ChTLR15/NF-κB-ChNLRP3/IL-β pathway probably play a vital role in attenuating the inflammatory injury caused by Eimeria infection. Thus, an in-depth exploration of inhibitors of the ChTLR15/NF-κB-ChNLRP3/IL-β signalling pathway and the effects on the attenuation of intestinal inflammatory injury caused by Eimeria infection may be a promising strategy to develop new anticoccidial preparations.

Increasing evidence has revealed that lactic acid bacteria effectively activate nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) antioxidant response elements (AREs), which further initiate the expression of serial antioxidant genes and exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [5,6,7]. Lin et al. reported that Lactobacillus plantarum AR501, isolated from Chinese food, markedly elevated the expression levels of Nrf2 and several antioxidant genes, including the glutathione S-transferase GSTO1, haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL), and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase-l (NQO1), in mouse livers [8], indicating that Nrf2/HO-1 is an important antioxidant signalling pathway. Another previous report demonstrated that Lactobacillus brevis 23017 effectively ameliorates intestinal inflammation and alleviates oxidative stress in animal models [9]. It was also reported that natural polyphenolic compounds, which are distributed extensively in medicinal plants, alleviate oxidative stress and inflammatory injury by upregulating the Nrf2 pathway [10, 11]. Ellagic acid (EA) is a polyphenolic compound that has been extracted from several vegetables, fruits and berries [12], has been extensively recognized to trigger the Nrf2 pathway, and displays antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [13]. Accumulating evidence reveals that the Nrf2 signalling pathway regulates the activation of the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, which further influences the activation of the NLRP3/IL-β pathway [14, 15]. Therefore, will EA and L. brevis 23017, two activators of the Nrf2 pathway, exert anticoccidial effects by inhibiting overactivation of the TLR/NLRP3/IL-β pathway? The aim of the present study was to explore whether oral administration of L. brevis 23017 alone and in combination with EA attenuated intestinal inflammatory injury caused by E. tenella infection by regulating the ChTLR15/NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway.

Materials and methods

Chickens, parasites, bacteria and drugs

One-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) Leghorn chickens were purchased from Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, China. E. tenella was stored in the Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology, Northeast Agricultural University, China, and propagated by challenging the chickens every six months to maintain pathogenicity. L. brevis 23017 was kindly provided by Professor Junwei Ge, Department of Preventive Veterinary Medicine, Northeast Agricultural University, China, and was reported to effectively ameliorate intestinal inflammation and alleviate oxidative stress in animal models [9]. EA was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biological Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Design of animal experiments

Two animal experiments were designed and performed. The design for animal Experiment 1 is outlined in Table 1. Eleven-day-old chickens were randomly allocated into 7 groups with 15 chickens in each group. Each chicken in Group 1 was orally gavaged with 200 μL of PBS (pH 7.2) (PBS group). Each chicken in Groups 2–4 was orally gavaged with a low (5.0 × 108 CFU in 200 μL of PBS), medium (5.0 × 109 CFU in 200 μL of PBS) or high (5.0 × 1010 CFU in 200 μL of PBS) dose of live L. brevis 23017; these groups were named the L/LB(+), M/LB(+), and H/LB(+) groups, respectively. Each chicken in Groups 5–7 was orally gavaged with a low (5.0 × 108 CFU in 200 μL of PBS), medium (5.0 × 109 CFU in 200 μL of PBS) or high (5.0 × 1010 CFU in 200 μL of PBS) concentration of heat-killed L. brevis 23017; these groups were called the L/LB(−), M/LB(−), and H/LB(−) groups, respectively. From 11 to 20 days of age, all chickens in each group in Experiment 1 were orally gavaged once a day.

The design for Experiment 2 is outlined in Table 1. Sixteen-day-old chickens were randomly divided into 5 groups with 15 chickens in each group. Each chicken in Group 1 was orally gavaged with 200 μL of PBS (pH 7.2) (PBS group). The chickens in Groups 2–4 were orally gavaged with L/LB(+), M/LB(+), or H/LB(+) once a day from 11 to 20 days of age combined with a low (15 mg/kg), medium (30 mg/kg) or high (60 mg/kg) dosage of EA once a day from 16 to 20 days of age; these groups were named the L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+), H/EA + H/LB(+) groups, respectively. Group 5 was designated as the challenged control group. At 21 days of age, all of the chickens in Experiments 1 and 2, except those in the PBS groups (nonchallenged control group), were orally gavaged with 50 000 E. tenella sporulated oocysts. Animal experiments were performed according to the regulations of the Ethics Committee for Animal Sciences at Northeast Agricultural University, Heilongjiang Province, China (NEAUEC20210332).

RNA extraction from the caeca

Chickens randomly selected from each group (n = 8) were euthanized, and the whole caecal tissue from each chicken was harvested for RNA extraction. Total RNA extraction was carried out using a purification kit (Sigma–Aldrich), and cDNA was synthesized as described in our previous report [4].

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR (qRT–PCR) was performed using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNase H Plus) (TaKaRa Biotech Corp., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT–PCR was carried out on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) according to the minimum information for publication of qRT–PCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines [16]. The mRNA expression levels of chicken glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the caecum were shown to be stable in the preliminary test and GAPDH was therefore selected as an internal reference gene. The primer pairs in this study were designed according to the target gene sequences from GenBank using Oligo 6.0 software and are shown in Table 2. When the amplification efficiencies of the 100-fold serially diluted target and reference gene cDNA samples were similar, the 2−ΔΔCt method was used to quantify the target gene [17].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Two grams of caecal tissue from each chicken was homogenized in 2 mL of saline with a high-speed tissue homogenizer (Kinematica, Switzerland). Then, the concentrations of Nrf2, superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH) and catalase (CAT) in the caecal homogenates from the different groups in Experiments 1 and 2 were determined by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). Operations were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations were calculated from standard curves.

Levels of in the caeca prior to challenge

The mRNA expression levels of Nrf2, HO-1, glutamyl-cysteine synthetase catalytic subunit (GCLC), glutamate-cysteine ligase modified subunit (GCLM), glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1), and NQO1 in the caeca of the chickens (n = 8) from different groups in Experiments 1 and 2, including three live L. brevis 23017 groups, three heat-killed L. brevis 23017 groups, and three EA combined with live L. brevis 23017 groups, were quantified using qRT–PCR at 21 days of age. The concentrations of Nrf2, SOD, GSH and CAT in the caeca of the chickens (n = 8) from each group were determined by ELISA.

Levels of ChTLR15/ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathway components in the caeca post-challenge

On Day 7 post-infection (pi), the caeca of the chickens (n = 7) from the different groups in Experiments 1 and 2, including three live L. brevis 23017 groups, three heat-killed L. brevis 23017 groups, and three EA combined with live L. brevis 23017 groups, were sampled for quantification of the mRNA expression levels of ChTLR15, ChMyD88, ChNF-κB, ChNLRP3, chicken cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 1 (ChCaspase-1), ChIL-1β, chicken interleukin 10 (ChIL-10) and ChIL-18 using qRT–PCR. The concentrations of ChTLR15, ChNLRP3, and ChIL-1β in the caeca of the chickens (n = 7) from each group were determined by ELISA.

Oxidant enzyme levels in the caeca post-challenge

The contents of malondialdehyde (MDA), a product of oxidative stress, in the caeca of the chickens (n = 7) from each group in Experiments 1 and 2 were detected using ELISA.

Anticoccidial effects

Chickens from each group in Experiments 1 and 2 were weighed at 21 days of age (before challenge) and at 28 days of age (on Day 7 post-challenge) to calculate the body weight gain (BWG) as previously described [18]. At 7 days post-challenge, caecal samples of the chickens (n = 7) from each group were harvested for gut lesion scoring based on the method described in a previous report [19]. Faecal samples from chickens housed separately within each group between Days 7 and 11 post-challenge were gathered, and oocyst counting was performed microscopically by three different scientists using the McMaster counting technique as described in a published report [18]. The oocyst reduction ratio was determined using the following formula: oocyst reduction ratio = (number of oocysts from chickens in the challenged control group-number of oocysts from the other groups)/number of chickens in the challenged control group × 100%.

Pathological changes in the caeca

On Day 7 pi, the caecum of each chicken from each group in Experiment 2 (n = 7) was sampled for gross pathological observation. The caecal samples were fixed in neutral buffered formalin (10%), embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). The histopathological lesions in the caecal tissues were observed using a light microscope (Nikon EX200).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD) and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison procedures with GraphPad Prism 5 software, and the differences between the mean values were analysed. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

mRNA expression levels of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway components in the caeca prior to challenge

Prior to oral challenge with E. tenella, the mRNA expression levels of Nrf2, HO-1, GCLC, GCLM, GPx1 and NQO1 in the caecal tissues of the chickens from the LB(+) groups were all significantly higher than those in the LB(−) groups (Figure 1) (p < 0.001). Among the three LB(+) groups, the mRNA levels of all target genes in the H/LB(+) group were higher than those in the M/LB(+) and L/LB(+) groups (Figure 1) (p < 0.001).

The mRNA levels of the components of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway found in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 1 prior to challenge. The mRNA levels of A Nrf2, B HO-1, C NQO1, D GCLC, E GCLM and F GPx1 in the caeca of chickens (n = 8) in each group in Experiment 1 were examined by real-time PCR. Three dosages (low, medium and high) of live and heat-killed L. brevis 23017 were used to establish the groups named L/LB(+), M/LB(+) and H/LB(+), and L/LB(−), M/LB(−) and H/LB(−), respectively. GAPDH was selected as an internal reference gene, and the 2−ΔΔCt method was applied to quantify the target gene. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

To explore whether the combination of LB(+) and EA provided higher antioxidant levels in the caeca, the chickens in Experiment 2 were gavaged with H/LB(+), M/LB(+) and L/LB(+) from 11 to 20 days of age and then with H/EA, M/EA and L/EA, respectively, from 16 to 20 days of age. The results showed that the chickens orally administered H/EA + H/LB(+) showed the strongest antioxidant levels in the caeca compared with chickens in the other groups (p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

The mRNA levels of the components of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway found in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 2 prior to challenge. The mRNA levels of A Nrf2, B HO-1, C NQO1, D GCLC, E GCLM and F GPx1 in the caeca of chickens (n = 8) in each group in Experiment 2 were quantified by real-time PCR. The groups were gavaged with low, medium and high dosages of EA and combined with L/LB(+), M/LB(+), and H/LB(+) to give groups named L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+), and H/EA + H/LB(+), respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

Protein levels of antioxidant enzymes in the caeca prior to challenge

Prior to challenge, the expression levels of antioxidant enzymes, including Nrf2, SOD, GSH and CAT, in the caeca of the chickens in the LB(+) and LB(−) groups, and in particular, the H/LB(+) group, were significantly upregulated compared with those in the PBS group (p < 0.01) (Figure 3). Notably, the H/EA + H/LB(+) group displayed the highest levels of antioxidant enzymes compared with the M/EA + M/LB(+), L/EA + M/LB(+) and control groups (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Protein levels of Nrf2, SOD, GSH and CAT in the caeca of chickens in the different groups in Experiment 1 prior to challenge. The protein expression levels of A Nrf2, B SOD, C GSH and D CAT in the caeca of chickens (n = 8) in each group in Experiment 1 were determined by ELISA. Three dosages (low, medium and high) of live and heat-killed L. brevis 23017 were used to establish the groups named L/LB(+), M/LB(+) and H/LB(+), and L/LB(−), M/LB(−) and H/LB(−), respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Protein levels of Nrf2, SOD, GSH and CAT in the caeca of chickens in the different groups in Experiment 2 prior to challenge. The protein expression levels of A Nrf2, B SOD, C GSH and D CAT in the caeca of chickens (n = 8) in each group in Experiment 2 were determined by ELISA. EA was combined with live L. brevis 23017 at three different dosages, and these groups were named L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+) and H/EA + H/LB(+). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Levels of ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 pathway components in the caeca post-challenge

After challenge with E. tenella sporulated oocysts, the mRNA expression levels of ChTLR15, ChMyD88, ChNF-κB, ChNLRP3, ChCaspase-1, ChIL-18 and ChIL-1β in the caeca of the chickens from the H/LB(+) (Figure 5) and H/EA + H/LB(+) (Figure 6) groups were significantly downregulated compared with the E. tenella-challenged control group (p < 0.001). The protein levels of ChTLR15, ChNLRP3 and ChIL-1β in the caeca from the H/LB(+) (Figure 7) and H/EA + H/LB(+) (Figure 8) groups displayed the same change trend as the mRNA levels.

The mRNA levels of the components of the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathway in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 1 post-challenge with E. tenella. On Day 7 pi with E. tenella, the caeca of chickens (n = 7) from each group in Experiment 1 were sampled for quantification of the mRNA expression levels of A ChTLR15, B ChMyD88, C ChNF-κB, D ChNLRP3, E ChCaspase-1, F ChIL-1β, G ChIL-18 and H ChIL-10 using real-time PCR. Three dosages (low, medium and high) of live and heat-killed L. brevis 23017 were established to give the groups named L/LB(+), M/LB(+) and H/LB(+), and L/LB(−), M/LB(−) and H/LB(−), respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

The mRNA levels of in the components of the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathway in the caeca of E. tenella-infected chickens from the different groups in Experiment 2. On Day 7 pi with E. tenella, the caeca of chickens (n = 7) from each group in Experiment 2 were sampled, and the mRNA expression levels of A ChTLR15, B ChMyD88, C ChNF-κB, D ChNLRP3, E ChCaspase-1, F ChIL-1β, G ChIL-18 and H ChIL-10 were quantified by real-time PCR. EA was combined with live L. brevis 23017 at three different dosages, and the groups were named L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+) and H/EA + H/LB(+). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

Protein levels of ChTLR15, NLRP3 and ChIL-1β in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 1 post-challenge with E. tenella. On Day 7 pi, the protein expression levels of A ChTLR15, B NLRP3 and C ChIL-1β in the caeca of each group of E. tenella-challenged chickens (n = 7) in Experiment 1 were determined by ELISA. The groups receiving low, medium and high dosages of live and heat-killed L. brevis 23017 were named L/LB(+), M/LB(+) and H/LB(+), and L/LB(−), M/LB(−) and H/LB(−), respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Protein levels of ChTLR15, NLRP3 and ChIL-1β in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. On Day 7 pi, the protein expression levels of A ChTLR15, B NLRP3 and C ChIL-1β in the caeca of each group of E. tenella-challenged chickens (n = 7) in Experiment 2 were determined by ELISA. EA was combined with live L. brevis 23017 at three different dosages, and the groups were named L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+) and H/EA + H/LB(+). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Levels of the oxidant enzyme malondialdehyde (MDA) in the caeca post-challenge

The levels of the oxidant enzyme malondialdehyde (MDA) in the caeca of E. tenella-infected chickens were significantly higher than those of all the gavaged and challenged groups (Figure 9) (p < 0.001). After challenge, the level of MDA in the caeca of chickens from the H/LB(+) group was significantly downregulated compared with both the M/LB(+) and L/LB(+) groups (p < 0.001). The MDA levels in the EA combined with LB(+) groups were lower than those in the LB(+) groups, but statistically significant differences were not observed among the three EA + LB(+) groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 9).

Protein levels of the oxidant enzyme malondialdehyde (MDA) in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiments 1 and 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. The protein expression levels of MDA in the caeca of chickens (n = 7) in each group in Experiments 1 (A) and 2 (B) were determined by ELISA. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Evaluation of anticoccidial effects

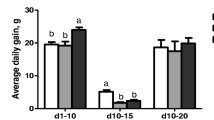

No chickens died from E. tenella infection. The average body weights of the chickens in the PBS group were higher than those in the other groups (p < 0.05). The H/EA + H/LB(+) group displayed the best effects on weight gain after E. tenella challenge, but a statistically significant difference was not observed compared with all of the LB(+), LB(−) and EA combined with LB(+) groups [p > 0.05 (Table 3)]. The average lesion scores in the caeca of the chickens in each treatment group were significantly lower than that in the E. tenella-infected control group (p < 0.01). Moreover, EA combined with LB(+), and especially H/EA combined with H/LB(+), displayed the lowest caecal lesion score compared with the other groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 10). The decreasing oocyst ratio from the chickens in each treatment group showed consistent changes in the caecal lesion scores and weight gain (Figure 11).

Caecal lesion scores of the chickens in different groups in Experiments 1 and 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. At 7 days post-challenge, caecal samples from each group of chickens (n = 7) in Experiments 1 and 2 were harvested for gut lesion scoring based on the method described by Johnson and Reid [19]. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

The decrease in oocyst ratio in the different groups in Experiments 1 and 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. Faecal samples chickens in each group raised in separate cages were gathered between Days 7 and 11 post-challenge. Oocyst counting was performed microscopically as described by Ma et al. [18], and the oocyst reduction ratio was determined. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001.

Pathological changes in the caeca of chickens

On Day 7 post-challenge, no obvious gross pathological changes in the caeca of the chickens in the PBS group were observed (Figure 12A). Gross pathological changes in the caeca of the chickens in the E. tenella-infected control group (Figure 12B) were remarkable, including notable swelling, haemorrhagic points on the surface of the caeca, and a thickened intestinal wall. The caeca of the chickens in the L/EA + L/LB(+), M/EA + M/LB(+) and H/EA + H/LB(+) groups, and especially the H/EA + H/LB(+) group, displayed slight gross pathological changes (Figures 12C–E). The results indicated that EA combined with LB(+) displayed the most significant anticoccidial effects.

Gross pathological changes in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. A The caeca of chickens in the PBS group showed no pathological changes. B On Day 7 post-challenge, the gross pathological changes in the caeca of chickens in the E. tenella-infected control group were remarkable and included swelling and haemorrhagic points on the surface of the caeca. However, the caeca of the chickens orally gavaged with the three different dosages (high, medium and low) of EA combined with live L. brevis 23017, the C L/EA + L/LB(+), D M/EA + M/LB(+)and E H/EA + H/LB(+)groups, and especially the H/EA + H/LB(+) group, displayed slight gross pathological changes.

No histopathological changes were observed in the caecal tissues in the PBS group, and the intestinal villi were arranged regularly (Figure 13A). Compared with the PBS group, there were clear histopathological lesions in the caecal tissues from the chickens in the E. tenella-infected control group (Figure 13B), including detachment of the intestinal villi, necrosis of the epithelial cells and congestion of the veins. In the L/EA + L/LB(+) (Figure 13C) and M/EA + M/LB(+) groups (Figure 13D), the structures of the caecal tissues were relatively complete, and a small number of red blood cells were observed. Importantly, no obvious histopathological changes were found in the caecal tissues of the chickens from the H/EA + H/LB(+) group (Figure 13E), and their intestinal villi were relatively complete and arranged regularly. The above results showed that oral gavage with EA combined with LB(+) provided better anticoccidial effects, and the H/EA + H/LB(+) group displayed the most significant effects against E. tenella infection.

Histopathological changes in the caeca of chickens from the different groups in Experiment 2 post-challenge with E. tenella. On Day 7 pi, the caeca of chickens from each group in Experiment 2 (n = 7) were fixed in neutral buffered formalin (10%), embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). A No histopathological changes were observed in the caecal tissues of the chickens in the PBS group. B Histopathological lesions in caecal tissues of the chickens in the infection control group displayed detachment of the intestinal villi, necrosis of the epithelial cells and congestion of the veins. In the C L/EA + L/LB(+)and D M/EA + M/LB(+)groups, the structures of caecal tissues were relatively complete, and a small number of red blood cells were observed. E In the H/EA + H/LB(+)group, no obvious histopathological changes to the caecal tissues were observed, and the intestinal villi were arranged regularly.

Discussion

Avian coccidiosis is caused by the intestinal protozoan Eimeria, which is widely found on chicken farms all over the world. E. tenella infection leads to severe intestinal inflammatory injury. In recent years, the relationship between innate immune responses stimulated by Eimeria parasites and inflammation have been a hot research topic. ChTLR15 is a unique type of innate immune receptor that recognizes fungal and bacterial secretory proteases [20]. ChTLR15 is unique to poultry; until now, its ligand has not been clear, as the known classical TLR agonists cannot activate it [21]. Our previous study showed that E. tenella sporozoites specifically triggered activation of the ChTLR15/NF-κB signalling pathway in vitro [4]. Moreover, the results from ChTLR15 knockdown and overexpression experiments showed that dynamic changes in all of the components in the ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathway led to dynamic changes in the ChTLR15/NF-κB pathway [4], which clearly proves that ChTLR15 effectively regulates the expression of key molecules in the ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathway.

After learning that the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 inflammatory signalling pathway is one of the key inflammatory pathways involved in the process of Eimeria infection, we were then interested in the signalling pathways that are capable of regulating the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 pathway and attenuating the intestinal inflammatory injury caused by Eimeria. It is widely accepted that the antioxidant signalling pathway Nrf2/HO-1 can inhibit oxidative stress and inflammatory injury by activating the expression of antioxidant response elements (AREs) [22, 23]. Moreover, the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway has been shown to regulate the TLR/NF-κB pathway [24]. Recent studies have reported that inonotus obliquus polysaccharide (IOP) can protect against Toxoplasma gondii infection, and this is closely related to activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and a reduction in TLR-mediated excessive inflammation through ARE activation and proinflammatory factor inhibition [25, 26].

In recent years, a variety of Chinese herbal extracts, such as Shi Ying Zi [27], berberine [28], the mushrooms Agaricus subrufescens and Pleurotus ostreatus [29], Cinnamomum verum [30] and Canary rue [31], have been reported to show anticoccidial effects to some extent. EA, a polyphenol extracted from certain medicinal plants, is a member of the tannin family that possesses several biological properties, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [32, 33]. However, the abilities of EA to relieve inflammatory intestinal injury caused by Eimeria remain elusive. In addition, lactic acid bacteria have been reported to regulate antioxidant stress [34]. Therefore, in the present study, L. brevis 23017, which was previously shown to ameliorate intestinal inflammation and alleviate oxidative stress [9], and EA were selected as activators of the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway to explore the effects of L. brevis 23017 alone or in combination with EA on the cross-regulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 and ChTLR15/ChNF-κB-ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β pathways in vivo. The results showed that live L. brevis 23017, especially at a high dosage, effectively activated the Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway.

To explore whether LB(+) combined with EA displayed a greater capability to trigger activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway, animal Experiment 2 was carried out, and three dosages of EA were administered. Compared with the M/EA + M/LB(+) and L/EA + L/LB(+) groups, the mRNA levels of the related molecules in the Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway and the protein levels of Nrf2 and the antioxidant enzymes in the caecal tissues of chickens in the H/EA + H/LB(+) group showed the strongest antioxidant effects (P < 0.01), suggesting that the antioxidant capacity activated by oral administration of LB(+) was significantly enhanced after combination treatment with EA.

To investigate whether activation of the Nrf2 signalling pathway inhibited intestinal inflammatory injury caused by E. tenella by regulating the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 pathway, chickens in Experiments 1 and 2 were infected with E. tenella by oral gavage with LB(+), LB(−) alone and LB(+) in combination with EA. The mRNA expression levels of key molecules in the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 pathway, the protein levels of ChTLR15, ChNLRP3 and ChIL-1β, and the protein levels of the oxidant enzyme MDA in the three LB(+) groups were significantly downregulated compared with those in the E. tenella infection control group. These results were reflected by the observed anticoccidial effects, including decreased lesion scores, alleviated histopathological changes in the caeca, increased body weight gain and decreased oocyst ratios. Importantly, the anti-inflammatory and anticoccidial effects on the chickens in the H/LB(+) + H/EA group were the best. In addition, in vitro experiments showed that the selected dosages of EA in animal Experiment 2 did not display direct roles on the development of E. tenella sporozoites (data not shown). The above results indicated that oral gavage of LB(+) combined with EA effectively enhanced the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, effectively inhibited the ChTLR15/ChNLRP3 inflammatory pathway triggered by E. tenella, and thus provided anti-inflammatory effects. The results from the present study are consistent with those of other reports, which showed that the combination of probiotics and herbs had strong potential functions [35, 36]. A possible explanation for the present results may be related to the following questions. Was the intestinal microbiota changed after the combination treatment of EA and L. brevis 23017? And was a novel EA-derived or L. brevis 23017-derived material produced? Recently, two reports showed that feed enzymes had the potential to reverse unfavourable caecal fermentation patterns [37] and ameliorate the deleterious effects of coccidiosis on intestinal health [38]. Thus, does the combination of EA and L. brevis 23017 influence intestinal enzymes? All of the above questions will be further analysed in our subsequent research work.

Taken together, these results showed that oral gavage with a high dosage of live L. brevis 23017 and ellagic acid produced significant anti-inflammatory effects by regulating the ChTLR15/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway in chickens. Therefore, the combination of this traditional Chinese medicine and lactic acid bacteria with excellent performance is a promising way to prevent and control Eimeria and restrict the use of anticoccidial drugs.

References

Peek HW, Landman WJ (2011) Coccidiosis in poultry: anticoccidial products, vaccines and other prevention strategies. Vet Q 31:143–161

Ademola IO, Ojo PO, Odeniran PO (2019) Pleurotus ostreatus extract inhibits Eimeria species development in naturally infected broiler chickens. Trop Anim Health Prod 51:109–117

Mulas F, Wang X, Song S, Nishanth G, Yi W, Brunn A, Larsen PK, Isermann B, Kalinke U, Barragan A, Naumann M, Deckert M, Schlüter D (2021) The deubiquitinase OTUB1 augments NF-κB-dependent immune responses in dendritic cells in infection and inflammation by stabilizing UBC13. Cell Mol Immunol 18:1512–1527

Li J, Yang X, Jia Z, Ma C, Pan X, Ma D (2021) Activation of ChTLR15/ChNF-κB-ChNLRP3/ChIL-1β signaling transduction pathway mediated inflammatory responses to E. tenella infection. Vet Res 52:15

Long X, Sun F, Wang Z, Liu T, Gong J, Kan X, Zou Y, Zhao X (2021) Lactobacillus fermentum CQPC08 protects rats from lead-induced oxidative damage by regulating the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE pathway. Food Funct 12:6029–6044

Wu Y, Chen H, Zou Y, Yi R, Mu J, Zhao X (2021) Lactobacillus plantarum HFY09 alleviates alcohol-induced gastric ulcers in mice via an anti-oxidative mechanism. J Food Biochem 45:e13726

Wang J, Zhang W, Wang S, Wang Y, Chu X, Ji H (2021) Lactobacillus plantarum exhibits antioxidant and cytoprotective activities in porcine intestinal epithelial cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:8936907

Lin X, Xi Y, Wang G, Yang Y, Xiong Z, Lv F, Zhou W, Ai L (2018) Lactic acid bacteria with antioxidant activities alleviating oxidized oil induced hepatic injury in mice. Front Microbiol 9:2684

Jiang X, Gu S, Liu D, Zhao L, Xia S, He X, Chen H, Ge J (2018) Lactobacillus brevis 23017 relieves mercury toxicity in the colon by modulation of oxidative stress and inflammation through the interplay of MAPK and NF-κB signaling cascades. Front Microbiol 9:2425

Hilliard A, Mendonca P, Russell TD, Soliman KFA (2020) The protective effects of flavonoids in cataract formation through the activation of Nrf2 and the inhibition of MMP-9. Nutrients 12:3651

Qin Z, Ruan J, Lee MR, Sun K, Chen P, Chen Y, Hong M, Xia L, Fang J, Tang H (2021) Mangiferin promotes bregs level, activates Nrf2 antioxidant signaling, and inhibits proinflammatory cytokine expression in murine splenic mononuclear cells in vitro. Curr Med Sci 41:454–464

Raudone L, Bobinaite R, Janulis V, Viskelis P, Trumbeckaite S (2014) Effects of raspberry fruit extracts and ellagic acid on respiratory burst in murine macrophages. Food Funct 5:1167–1174

Aslan A, Hussein YT, Gok O, Beyaz S, Erman O, Baspinar S (2020) Ellagic acid ameliorates lung damage in rats via modulating antioxidant activities, inhibitory effects on inflammatory mediators and apoptosis-inducing activities. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27:7526–7537

Fujita K, Maeda D, Xiao Q, Srinivasula SM (2011) Nrf2-mediated induction of p62 controls Toll-like receptor-4-driven aggresome-like induced structure formation and autophagic degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:1427–1432

Yu Y, Wu DM, Li J, Deng SH, Liu T, Zhang T, He M, Zhao YY, Xu Y (2020) Bixin attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activity and activating NRF2 signaling. Front Immunol 11:593368

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaf MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT (2009) The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantita tive real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55:611–622

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2[-Delta Delta C(T)] method. Methods 25:402–408

Ma D, Ma C, Pan L, Li G, Yang J, Hong J, Cai H, Ren X (2011) Vaccination of chickens with DNA vaccine encoding Eimeria acervulina 3–1E and chicken IL-15 offers protection against homologous challenge. Exp Parasitol 127:208–214

Johnson J, Reid WM (1970) Anticoccidial drugs: lesion scoring techniques in battery and floor-pen experiments with chickens. Exp Parasitol 28:30–36

de Zoete MR, Bouwman LI, Keestra AM, van Putten JP (2011) Cleavage and activation of a Toll-like receptor by microbial proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:4968–4973

Boyd AC, Peroval MY, Hammond JA, Prickett MD, Young JR, Smith AL (2012) TLR15 is unique to avian and reptilian lineages and recognizes a yeast-derived agonist. J Immunol 189:4930–4938

Dong Q, Hou H, Wu J, Chen Y (2016) The Nrf2-ARE pathway is associated with Schisandrin b attenuating benzo(a)pyrene-Induced HTR cells damages in vitro. Environ Toxicol 31:1439–1449

Xu X, Zhang L, Ye X, Hao Q, Zhang T, Cui G, Yu M (2018) Nrf2/ARE pathway inhibits ROS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in BV2 cells after cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Inflamm Res 67:57–65

Rahman MS, Alam MB, Kim YK, Madina MH, Fliss I, Lee SH, Yoo JC (2021) Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 by peptide YD1 attenuates inflammatory symptoms through suppression of TLR4/MYyD88/NF-kappa B signaling cascade. Int J Mol Sci 22:5161

Xu L, Yu Y, Sang R, Ge B, Wang M, Zhou H, Zhang X (2020) Inonotus obliquus polysaccharide protects against adverse pregnancy caused by Toxoplasma gondii infection through regulating Th17/Treg balance via TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Int J Biol Macromol 146:832–840

Ding X, Ge B, Wang M, Zhou H, Sang R, Yu Y, Xu L, Zhang X (2020) Inonotus obliquus polysaccharide ameliorates impaired reproductive function caused by Toxoplasma gondii infection in male mice via regulating Nrf2-PI3K/AKT pathway. Int J Biol Macromol 151:449–458

Song X, Li Y, Chen S, Jia R, Huang Y, Zou Y, Li L, Zhao X, Yin Z (2020) Anticoccidial effect of herbal powder “Shi Ying Zi” in chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Animals 10:1484

Nguyen BT, Flores RA, Cammayo PLT, Kim S, Kim WH, Min W (2021) Anticoccidial activity of berberine against Eimeria-infected chickens. Korean J Parasitol 59:403–408

Lima GA, Barbosa BFS, Araujo RGAC, Polidoro BR, Polycarpo GV, Zied DC, Biller JD, Ventura G, Modesto IM, Madeira AMBN, Cruz-Polycarpo VC (2021) Agaricus subrufescens and Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms as alternative additives to antibiotics in diets for broilers challenged with Eimeria spp. Br Poult Sci 62:251–260

Qaid MM, Al-Mufarrej SI, Azzam MM, Al-Garadi MA (2021) Anticoccidial effectivity of a traditional medicinal plant, Cinnamomum verum, in broiler chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Poult Sci 100:100902

López AM, Muñoz MC, Molina JM, Hermosilla C, Taubert A, Zárate R, Hildebrandt I, McNaughton-Smith G, Eiroa JL, Ruiz A (2019) Anticoccidial efficacy of Canary rue (Ruta pinnata) extracts against the caprine apicomplexan Eimeria ninakohlyakimovae. J Anim Sci 97:101–110

Zeb A (2018) Ellagic acid in suppressing in vivo and in vitro oxidative stresses. Mol Cell Biochem 448:27–41

BenSaad LA, Kim KH, Quah CC, Kim WR, Shahimi M (2017) Anti-inflammatory potential of ellagic acid, gallic acid and punicalagin A&B isolated from Punica granatum. BMC Complement Altern Med 17:47

Feng T, Wang J (2020) Oxidative stress tolerance and antioxidant capacity of lactic acid bacteria as probiotic: a systematic review. Gut Microbes 12:1801944

Prakasita VC, Asmara W, Widyarini S, Wahyuni AETH (2019) Combinations of herbs and probiotics as an alternative growth promoter: an in vitro study. Vet World 12:614–620

Wang Y, Li J, Xie Y, Zhang H, Jin J, Xiong L, Liu H (2021) Effects of a probiotic fermented-herbal blend on the growth performance, intestinal flora and immune function of chicks infected with Salmonella pullorum. Poult Sci 100:101196

Yang L, Oluyinka OA (2021) Exogenous enzymes influenced Eimeria-induced changes in cecal fermentation profile and gene expression of nutrient transporters in brolier chickens. Animals 11:2698

Elijah GK, Haley L, Reza AMK, Rob P, John RB (2019) Utility of feed enzymes and yeast derivatives in ameliorating deleterious effects of coccidiosis on intestinal health and function in broiler chickens. Front Vet Sci 6:473

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the other members of the Molecular Pathological Laboratory of the College of Veterinary Medicine, Northeast Agricultural University, China, for their kind help during the performance of the animal experiments.

Funding

This study was funded by a Grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31973003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM designed the experiments and amended the manuscript. XY, XP, CM, ZJ, WZ, BB, and HC carried out the experiments. XY and CM completed the original draft of the manuscript and the statistical analysis. XP and CM prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments were performed according to the regulations (NEAUEC20210332) of the Ethics Committee for Animal Sciences at Northeast Agricultural University, Heilongjiang Province, China.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Pan, X., Jia, Z. et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus brevis 23017 combined with ellagic acid attenuates intestinal inflammatory injury caused by Eimeria infection by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway. Vet Res 53, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01042-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01042-z