Abstract

Purpose

The abundance and composition of nitrogen transformation-related microbes with certain environmental parameters for living conditions provide information about the nitrogen cycle in the Yangtze Estuary. The aim of this study was to explore the impacts of salinity on four N-related microbes and reveal the phylogenetic characteristics of microorganisms in the Yangtze Estuary ecosystem. A molecular biology method was used for the quantitation and identification of four microbes in the Yangtze River: ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), denitrifying microbes (nirS-type), and anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria. Sequence identification was performed on the levels of phylum, class, order, family, and genus, and the sequences were then matched to species.

Result

The results showed that the dominant species of AOA were crenarchaeote enrichment cultures, thaumarchaeote enrichment cultures, and Nitrosopumilus maritimus cultures, and the dominant AOB species were betaproteobacterium enrichment cultures and Nitrosomona sp. The denitrifying microbes were identified as the phylum Proteobacteria, classes Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria, and the species Thauera selenatis. The dominant species of the anammox bacteria was Candidatus Brocadia sp. In the estuarine sediments of the Yangtze River, the nirS gene abundance (1.31 × 107–9.50 × 108 copies g−1 sediments) was the highest among all the detected genes, and the abundance of bacterial amoA, archaeal amoA, and nirS was significantly correlated. Closely correlated with the abundance of the bacterial amoA gene, salinity was an important factor in promoting the abundance and restraining the community diversity of AOB. Moreover, the distribution of the AOB species exhibited regional patterns in the estuarine zone.

Conclusions

The results indicated that salinity might promote abundance while limiting the diversity of AOB and that salinity might have reverse impacts on AOA. Denitrifying microbes, which showed a significant correlation with the other genes, were thought to interact with the other genes during nitrogen migration. The results also implied that AOA has a lower potential nitrification rate than AOB and that both the anammox and denitrification processes (defined by nirS gene) account for N2 production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen is a key element for living organisms but is also one of the main causes of eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems (Bowen and Valiela 2001). There has been growing concern about the migration and transformation of nitrogen in recent years (Galloway et al. 2008). Because of the strong interaction between land and sea, the gradients of various physical, chemical, and biological factors have changed sharply (Kirwan and Megonigal 2013), and the processes of the nitrogen cycle in estuary areas have become more complex. Estuaries are typically environmentally vulnerable and sensitive zones in which the stability of ecosystems is easily disturbed and destroyed by natural and artificial factors. In addition, estuarine areas are rich in various nutrients and pollutants and are mixed with seawater and freshwater currents. Thus, environmental parameter gradients such as salinity are formed; as a result, the microbial community structure of estuaries is unique, as these areas contain abundant information about unknown genetics and ecology (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2016). Therefore, studying the distribution and community composition of microbial flora in estuarine water is of great significance for the nitrogen cycle in ecotones.

The degradation of organic nitrogen contamination can be accomplished by the processes of ammonia oxidation, nitrification, denitrification, and anaerobic ammonia oxidation (Holland 1998; Zehr and Ward 2002; Trimmer et al. 2003). The whole process, including organic nitrogen, entails oxidation to ammonia (ammonification), which is subsequently oxidized to nitrite and then to nitrate (nitrification). Then, nitrate is reduced to nitrite and then to dinitrogen gas (denitrification) (Kuypers et al. 2018). In the first stage, the corresponding functional microorganisms are ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA). Both AOB and AOA have been proven to be capable of oxidizing ammonia under aerobic conditions. These reactions are catalyzed by ammonia monooxygenase and coded by amoA (Konneke et al. 2005). Baptista (2014) adopted a reliable quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) technique to quantify the amoA gene and found an order-of-magnitude differences in AOB cell abundances, which indicated that the amoA gene is generally used as a specific marker to provide a scientific explanation for the mechanism of ammoxidation. Denitrifying microbes dominate the denitrification stage. Genes of interest include nitrite reductase genes (nirS and nirK), the nitric oxide reductase gene (norB), and the nitrous oxide reductase gene (nosZ) (Zhou et al. 2011). Among these, the nitrite reductase genes have been studied more extensively (Ligi et al. 2014; Zhi and Ji 2014). Previous studies have found that the nirS-type functional gene could reveal patterns of abundance and community structure (Yin et al. 2012; Deslippe et al. 2014) and the dominant species (Yu et al. 2018) of denitrifying organisms.

In addition, the ammoxidation process that proceeds under anaerobic conditions was also found to be a nonnegligible part of the global nitrogen cycle, namely, anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria, which were theoretically proposed by Broda (1977). Anammox bacteria exist in anoxic environments (Mulder et al. 1995) and have the ability to reduce nitrite into N2 with ammonium as the electron donor, playing an important role in the nitrogen cycle and nitrogen pollution control (Ding et al. 2013). A continental surface may offer great possibilities and environmental conditions for anammox bacteria in freshwater wetland ecosystems (Zhu et al. 2010). Hydrazine synthase is a unique biomarker for studying the presence and biodiversity of anammox bacteria (Harhangi et al. 2012). One of its subunits is encoded by the functional gene hzsB; thus, researchers generally use the hzsB gene to characterize the community structure of anammox bacteria (Zhu et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2017). In recent years, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), 16S rRNA-based phylogeny analysis, and PCR have been used for the quantitation and identification of anammox bacteria and have indicated that the most common anammox bacteria in the environment are Candidatus Scalindua, Candidatus Brocadia, and Candidatus Kuenenia (Schmid et al. 2005; Yoshinaga et al. 2011).

Because of the important role of microorganisms in nitrogen cycling, many studies have focused on the relationship between microbial characteristics and the living environment or its niches. Previous studies mostly focused on gene abundance and community structure diversity in different environments, such as natural soil (Tourna et al. 2008) and aquarium biofiltration systems (Urakawa et al. 2008), and the effects of different soil fertility on populations of AOA and AOB (Bai et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016a). Salinity has generally been considered an influencing parameter on archaeal and bacterial cells (Yang et al. 2015) as well as on anammox bacteria (Wei et al. 2016) and denitrifying organisms (Yoshie et al. 2004). Researchers have suggested that because of changes in salinity gradients (Bernhard et al. 2005; Zheng et al. 2013) and the influence of habitat ecotones or the transition zones of ecosystems (Huang et al. 2016), the structure and distribution of the nitrogen-transformation-related microbial communities have obvious regularity, but analyses of the effect of environmental parameters on the four microbes in the same location have been rare.

The Yangtze River is one of the main channels in China. Large amounts of sediment and seawater flood into this river every year. In addition, the salinity in the Yangtze Estuary is also affected by the intrusion of saltwater downstream of open seas (Chen et al. 2016). The aim of this study was to explore the impacts of salinity on nitrogen transformation-related microbes and reveal the phylogenetic characteristics of microorganisms in the Yangtze Estuary ecosystem. For this purpose, distribution regulation associated with environmental factors and the phylogenetic community structure of AOB, AOA, denitrifying microbes (nirS-type), and anammox in the estuary of the Yangtze River was assessed through a specific molecular biology method. Classification of different levels was accomplished, and correlations with the water quality indices were analyzed. The following questions were proposed before the study:

1. Is salinity the environmental factor that restrains the gene abundances of the four bacteria?

2. How do the diversity and community structure of microorganisms react when salinity gradients are regulated?

3. What is the dominant form of nitrogen transformation in the Yangtze River Estuary?

Materials and methods

General situation

The Yangtze River Estuary starts at the Xuliujing Wharf and extends to the East China Sea, spanning a total length of approximately 181.8 km. The estuarine section is fan-shaped and is divided into the north tributary and south tributary. The latter is divided into the north port and south port, as shown in Fig. 1. According to the salinity gradient, four regions were included in the sampling area, as shown in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Fig. 1. The four regions are S1, the freshwater upstream with sampling sites 1–3; S2, the south tributary transition area with sampling sites 4–7; S3, the area between the south port and north port with sampling sites 8–11; and S4, the north branch of the estuary area with sampling sites 12–14. Sediment samples were collected from the junction of water and sediments at each sampling site by a grab sampler and then sealed and stored at 4 °C. After being transported back to the laboratory, the samples were stored at 4 °C and − 80 °C for chemical analysis and DNA extraction, respectively.

Distribution of sampling sites in the Yangtze River Estuary. Sampling region S1 represents sampling sites 1–3 from freshwater upstream, sampling region S2 represents sampling sites 4–7 in the south tributary transition area, sampling region S3 represents sampling sites 8–11 in the area between the south port and north port, and sampling region S4 represents sampling sites 12–14 in the north branch of the estuary area

Chemical analysis

The NH4+-N and NO3−-N concentrations in the sediment samples from the four sampling areas were measured using the potassium chloride solution-spectrophotometric method (China National Soil Quality Standard, GB 15618-1995) (He et al. 2015). Briefly, samples were extracted with a 2 mol/L KCl solution and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter membrane. NH4+-N was subsequently determined through Nessler’s reagent spectrometry, and NO3−-N was determined using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer. The salinity, pH, and temperature measurements were detected in situ with an inline YSI EXO1 monitor.

Biological analysis

We lyophilized a 0.33-g sediment sample and used the Fast DNA Spin Kit for Soil DNA (MP Biomedicals, USA) to extract the total DNA. The mass of total DNA was detected using 1% gel electrophoresis, and the concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). PCR amplification was conducted with a Promega Agarose Gel DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The PCR product was gel-purified and ligated to pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison) and then transferred to JM109 competent cells (Takara, Dalian). Then, the combination was coated on a Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Finally, after incubation, the blue-white selection was conducted, and five white clones were selected randomly and then amplified. The positive clones were sequenced (QingKexinye Biotechnology Limited Company, Beijing), and the obtained sequences were analyzed using the BLAST tool to aid in the selection of the closest matches (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Next, the obtained sequences were aligned using the Clustal_X program (Wang et al. 2018). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with 98% similarity were selected using UCLUST (Cole et al. 2009; Luria et al. 2014). The α-diversity indices were then calculated using Mothur to characterize the richness of each bacterium. Phylogenetic trees of the four bacteria were constructed using MEGA 5 software, with the neighbor-joining method based on different levels. The functional gene sequences were submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the accession number MN602086-MN602141.

Quantitative analysis of the gene abundances of the four microbial groups mentioned above, i.e., amoA, nirS (Zheng et al. 2015), and hzsB, in the sediment samples was conducted through real-time qPCR. All primers and protocols (Zheng et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2012) that were used for amplification are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S2. The quantitative mixture totaled 20 μL in volume, including 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq enzyme, 0.4 μL of ROX 50, 0.4 μL of BSA (Takara Bio Company, DaLian), and 0.5 μL of each primer. Moreover, 2 μL of the DNA template was used, and the final volume was adjusted to 20 μL with H2O. An ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR system (CA, USA) was used for the quantitative amplification, and the SYBR Green method was used for quantitation. The plasmid DNA with known copies was diluted using 10 gradients. Thus, seven standard samples were obtained and were amplified at the same time, and a standard curve was obtained. The quantitative PCR results of gene abundance were calculated using 7300 SDS System software. The amplification efficiency between 90% and 110% and correlation coefficients above 0.98 was applied. A negative control was set up in the experiment, and each sample was determined three times.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. Pearson correlations and Student’s t tests were used to analyze the abundances of the four functional genes and the water quality indices. Plotting was conducted using Origin 8.5 and Microsoft Excel. Furthermore, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA version 5.0.

Results and discussion

Environmental parameters in the sediments

The values of the environmental parameters of temperature, pH, salinity, NH4+-N, and NO3−-N in the samples in the four sampling areas with the ratio of NH4+-N and NO3−-N are shown in Additional file 1: Table S3. The proportions of NH4+-N and NO3−-N are shown in the pie chart in Fig. 1. The concentrations of both ammonia and nitrate nitrogen fluctuated greatly. In addition, the concentration of NH4+-N was higher than that of NO3−-N at sampling points 5 and 7 in S2 and 11 in S3; at other sites, the nitrate concentrations were higher than the ammonia concentrations.

Identification of the sequence

Significant sequences were detected, in which 64 copies of AOA and 75 copies of AOB were obtained. In addition, sequences of denitrifying microbes (based on nirS gene, 53 copies) and anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (26 copies) were also obtained. All sequences at different sampling sites were classified based on the flora of microorganisms. Moreover, Fig. 2 shows the proportion of four microbial sequences at species levels (the proportion of the four microbial sequences at species levels in the four sampling regions are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S2). As exhibited, the majority of AOA were generally identified as the phyla Thaumarchaeota and Crenarchaeota and the genera Nitrosopumilus, Nitrososphaera, and Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus. AOB were identified as the phylum Proteobacteria and the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira (the identification of the sequences in S1–S4 at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels is shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The sequence identification was similar to those in the adjacent waters of Rushan Bay (He et al. 2018), terrestrial environments (Oton et al. 2016), soil microorganisms (Verhamme et al. 2011), tropical stream sediments (Reis et al. 2015), and the Pacific Ocean (Church et al. 2010). In addition, the denitrifying microbes were identified as the phylum Proteobacteria and classes Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria, which was similar to Kim’s research findings (2016). Sequence analysis showed that the anammox bacteria were identified as the phylum Planctomycetes and the order Candidatus Brocadiales, which was similar to Jetten’s research findings (2001), and genera Candidatus Brocadia, Candidatus Jettenia, Candidatus Kuenenia, and Candidatus Scalindua. To date, the marine anammox bacteria that have been found in marine water columns and sediments worldwide are almost exclusively Ca. Scalindua species, which are capable of reducing nitrate via nitrite to ammonium under limited electron acceptor conditions by using organic matter and the uptake of small organic compounds (van de Vossenberg et al. 2013).

Proportions of each taxon are shown in Fig. 2. The dominant species varied in the different sampling regions from S1–S4. The shift and differentiation pattern are common because of the environmental parameters of nitrogen content (van der Star et al. 2008) and salinity (Zhou et al. 2017). However, in this research, the dominant species of AOA were basically crenarchaeote enrichment cultures,thaumarchaeote enrichment cultures, and Nitrosopumilus maritime cultures. N. maritimus cultures could be utilized to determine whether putative gene coding for novel crenarchaeal metabolisms was functional (Prosser and Nicol 2008; Martin-Cuadrado et al. 2008). AOB were Betaproteobacterium enrichment cultures and Nitrosomona sp., which have a high tolerance for elevated ammonia concentrations and are believed to contribute significantly to the global production of nitrous oxide (Koops et al. 1991; Chain et al. 2003). Denitrifying organisms included Thauera selenatis, which has been found to obligate autotrophic denitrifiers and dominate in hydrogenotrophic denitrification (Mao et al. 2013; Xing et al. 2018). Furthermore, the anammox bacteria were Candidatus Brocadia sp. Among the five genera identified to date (Narita et al. 2017), members of Ca. Brocadia are considered as growth-rate strategists with a high growth rate and low substrate affinity (van der Star et al. 2008). The functions of the identified dominant species indicated that nitrogen transformation activities caused by the four microbes might coexist.

Alpha diversity index and OTU

In order to investigate the richness and community distribution of the four microbes, variance analysis was conducted between alpha diversity indices, and the results are shown in Table 1. Among all sampling sites, the diversity of the denitrifying microbes (based on nirS gene) was significantly different from the AOA, denitrifying microbes at the Shannon, Chao 1, and Ace indices, indicating that the diversity of denitrifying microbes is the highest. Since no significant difference of any indices was found in the anammox bacteria and AOA, and both of them were lower than AOB, it could be inferred from the table that AOB is the second most diverse microbe.

The results of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for AOA, AOB, denitrifying microbes, and anammox bacteria showed that denitrifying microbes had the highest OTU number, 46, followed by AOB (23), AOA (15), and anammox bacteria (14), and the order was consistent with the α-diversity indices. The highest number of OTUs for the denitrifying microbes was in S2 (15 OTUs), AOB was in S2 (16 OTUs), AOA was in S3 and S4 (9 OTUs), and anammox bacteria was in S2 and S3 (6 OTUs), suggesting that the moderate salinity regions of S2 and S3 are suitable for the growth of four groups (Biller et al. 2012). No overlaps of OTUs of these microbes were found in the four sampling regions except AOA, which had 2 OTUs in the overlaps of all sampling regions (shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S3), indicating that AOA has a strong adaptability to different salinity gradients. A previous study confirmed that the AOA ecotype might tolerate elevated salinity (Blainey et al. 2011) and could outcompete AOB in terms of growth and ammonia oxidation activity under moderate- and high-salinity conditions (Zhang et al. 2015).

Phylogenetic tree construction

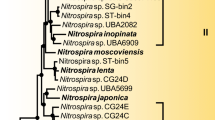

The reference species were obtained by matching with the BLAST tool in the GenBank database. The sequence closest to the reference species in each sampling region was optimized, and the simplified phylogenetic tree of each microbe was drawn, as shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6. The phylogenetic tree of AOA suggested that the species in S4 shows an obvious affiliation with intertidal sediment (JQ345772) and Nitrosopumillaceae archaeon MY1 (HQ33117), while the species in S2 might be similar to those in intertidal sediments (KC735320). In S1, the species were similar to those in sediments in the Beiyun River Nitrosoarchaeum limmia SFBIN (AECG01000066). The species in S3 had no specific affiliations.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of archaeal amoA gene sequences in all sampling sites in the Yangtze River Estuary, where the white up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S1, the black up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S2, the white down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S3, the black down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S4, and next to these symbols are the numbers of sampling sites; the black circle represents the reference sequences gained from GenBank, and the two capital letters and six numbers in brackets are the accession numbers of the reference sequences. Bootstrap values close to the nodes are greater than 50% of 1000 replicates. The scale indicates 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of bacterial amoA gene sequences in all sampling sites in Yangtze River Estuary, where the white up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S1, the black up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S2, the white down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S3, the black down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S4, and next to these symbols are the numbers of sampling sites; the black circle represents the reference sequences gained from GenBank, and the two capital letters and six numbers in brackets are the accession numbers of the reference sequences. Bootstrap values close to the nodes are greater than 50% of 1000 replicates. The scale indicates 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of hzsB gene sequences in all sampling sites in Yangtze River Estuary, where the white up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S1, the black up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S2, the white down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S3, the black down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S4, and next to these symbols are the numbers of sampling sites, the black circle represents the reference sequences gained from GenBank, and the two capital letters and six numbers in brackets are the accession numbers of the reference sequences. Bootstrap values close to the nodes are greater than 50% of 1000 replicates. The scale indicates 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of nirS gene sequences in all sampling sites in Yangtze River Estuary, where the increment represents the sampling sites in S1, the black up-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S2, the white down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S3, the black down-pointing triangle represents the sampling sites in S4, and next to these symbols are the numbers of sampling sites; the black circle represents the reference sequences gained from GenBank, and the two capital letters and six numbers in brackets are the accession numbers of the reference sequences. Bootstrap values close to the nodes are greater than 50% of 1000 replicates. The scale indicates 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site

For AOB, it is worth noting that the species in the four sampling regions showed obvious regional characteristics. In S1, the species were similar to soil (EU625169). In S2, the species were close to Nitrosospira (AY123821), Nitrosovibrio (AY123824), and Nitrosomonas (AF272406). In S3, the species were similar to species in paddy soil (FJ755469). Moreover, the species in S4 were similar to Nitrosospira sp. N15 (AY12382). The regional distribution of AOB suggested that variation in the environmental factors may influence the patterns of microorganisms. The sediments at sampling sites 1, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, and 14 were collected far from shore, whereas those from 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, and 11 were collected near the shore. It was obvious that species in the near-shore samples 2, 3, 7, 8, and 11 were similar to species in soil sediments (EU625169, FJ755469, and EU625023), whereas the far-shore samples were less regular. This finding might be attributed to the edge effect in ecotones (Lei et al. 2011), which is generally characterized by acute variation in the composition and structure of species (Miao et al. 2006). Located in the freshwater ecotone of the community, S1 might have marginal effects on the microbial community providing biogeographical habitats (Zhu et al. 2013).

The anammox bacteria, except the species in S4, were similar to Candidatus Scalindua. sp. (JN704474) and Candidatus Brocadia sp. (JN704470), and in S3, the species were similar to Candidatus Kuenenia sp. (JN704475); no obvious similar strains were found for the species in S1 and S2.

For the denitrifying microbes (based on nirS gene), the species in S1 were similar to those in a Tibetan Plateau wetland (KC468943), intertidal sediments of the Yangtze Estuary (KM891947), and the sediments of the Jiulongjiang and Minjiang clones (JX941962); the species in S2 were similar to those in the San Francisco Bay (KR060797) and the Yellow River Estuary (KX952167); the species in S3 were similar to those in intertidal marshes (KT444066) and Yangtze lakes (MF776477); and the species in S4 were similar to those in sediments of the Yangtze Estuary and its adjacent area in the East China Sea (MF420548). Overall, the species in S4 were less complex than the others, which might be attributed to the stress of salinity.

Gene abundances at the sampling sites

The order of gene abundance of the four functional genes in the sampling regions was S1 > S4 > S2 > S3. The specific values are shown in Additional file 1: Table S4. Among all sampling regions, the gene abundance of nirS was significantly higher than that of bacterial amoA (Student’s t test, P = 0.011), archaeal amoA (P = 0.011), and hzsB (P = 0.031). Additionally, the gene abundance of bacterial amoA was significantly higher than hzsB (P = 0.008). The results in Fig. 7 show that the abundance of bacterial amoA was (by dry weight) 4.80 × 104 (S2) − 1.93 × 107 copies g−1 sediments (S4). The range in abundance of archaeal amoA was (by dry weight) 2.88 × 104 (S3) − 4.78 × 106 copies g−1 sediments (S1). In addition, the hzsB gene abundance was (by dry weight) 2.97 × 105 (S2) − 6.77 × 106 copies g−1 sediments (S1). Finally, the abundance of the nirS gene was (by dry weight) 2.61 × 106 (S3) − 9.50 × 108 copies g−1 sediments (S1).

Obviously, except for bacterial amoA, the greatest abundance of the other genes was found in S1, indicating that AOB bacteria are adaptable to relatively higher salinity levels, whereas the others are suitable to relatively lower salinity conditions (Blainey et al. 2011; Mosier et al. 2012). However, the AOB in the estuary of Hangzhou Bay were not sensitive to salinity variation, whereas the AOA were abundant under moderate salinity (Zhang et al. 2015). In addition, the bacterial amoA was highest at sampling site 14 in S4, which might be because the highest salinity level was measured there (4.17 psu). The highest hszB gene abundance of anammox bacteria was at site 2 in S1. Moreover, the abundance of archaeal amoA was highest at site 3 in S1, and there was no variation trend in the other sampling regions. Hence, it could be expected that S1 might be the ecotone for the growth of anammox bacteria and AOA microorganisms. Although the conditions at S1 promoted a higher abundance of archaeal amoA, hszB, and nirS genes, not all bacteria were rich in diversity. One explanation for the higher abundances of bacterial amoA and nirS and richer diversity of AOA and denitrifying microbes (based on nirS gene) in S4 is that the exchange of salt and freshwater in the intersection zone resulted in unequal salinity, which is one of the important factors affecting the structure of the microbial community (Awata 2012). Compared to the other bacteria, the gene abundance of nirS was one or two orders of magnitude higher, especially in S1 and S4, and the diversity was highest, especially in S2. Salinity did not seem to restrict the growth and richness of denitrifying microbes in this research. In the Yangtze Estuary, Zheng found that the diversity of the nirS gene was significantly richer at the lower salinity sites than at the higher salinity sites, and the abundance was merely related to salinity in the intertidal sediments (Zheng et al. 2015).

Regarding the near-shore and far-shore samples mentioned above, an obvious trend was found; namely, all the far-shore sediment samples had a higher bacterial amoA gene abundance than did archaeal amoA, whereas in the sediments from the near-shore area, the former showed no superiority. This finding was similar to the results of Kim, who found a higher gene abundance and activities in near-shore sediments than in stream sediments (Kim et al. 2016). This finding offers an explanation for the higher abundance of the archaeal amoA gene at near-shore sampling site 3.

Correlation analysis

Anammox, denitrification, and aerobic ammonia oxidation processes have synergistic effects (Zhou 2006). Anammox, which uses NH4+-N as the electron donor, nitrate or nitrite as the electron acceptor, and CO2 as the carbon source, produces a certain amount of N2 (Mulder 1995). Denitrification converts nitrate or nitrite into N2, consuming chemical oxygen demand (COD), producing CO2, and providing inorganic carbon sources for anammox. Aerobic ammonia oxidation converts NH4+-N to nitrate or nitrite by AOB and AOA, providing reactors for the anammox and denitrification processes (Xu et al. 2017). It could thus be inferred that nitrogen-related microbes were correlated with each other because of the interaction within the nitrogen cycle. The correlation analysis in Table 2 showed that bacterial amoA with nirS, archaeal amoA with nirS, archaeal amoA with hzsB, and nirS with hzsB were significantly correlated, suggesting that aerobic ammonia oxidation is correlated with denitrification (defined by nirS gene in this work) and anammox. Moreover, some correlations were found in S2 and S3, and the aerobic ammonia oxidation was closely related to the denitrification process and anammox, implying that there are interactions within the moderate-salinity region. Zhi et al. (Zhi and Ji 2014) confirmed an interaction and ecological association among nitrogen-related microbial communities due to their similar environmental conditions and interrelated but distinct ecological niches (Ji et al. 2012).

Environmental parameters, such as pH, temperature, salinity, and the concentrations of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphorus, affect the growth and metabolism of N-related microbes, which are commonly found in terrestrial and marine sediments (Zhang et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2016; Lee and Francis 2017). The correlation analysis of the environmental factors with the gene abundances of the four functional genes are shown in Table 3. There was a significant correlation between bacterial amoA gene abundance and salinity in every sampling region, but there were no correlations between the other microbial genes and the ammonia or nitrate contents. The significant correlation suggested that salinity is the dominant limiting factor for AOB, which was consistent with the regional pattern exhibited in the phylogenetic tree. Salinity appeared to be an influential factor for archaeal and bacterial cells (Yang et al. 2015). In this study, it promoted abundance while restricting the diversity of AOB and had reverse impacts on AOA. Specifically, the abundance of the bacterial amoA gene was highest in S4, whereas the abundance of archaeal amoA was the highest in S1; the diversity of AOB was richer in S2, whereas that of AOA was richer in S3 and S4, implying that salinity is conducive to the richness and diversity of some microbial groups. Since the activity of anammox bacteria, represented by Candidatus Brocadia, could be inhibited by the presence of nitrite (Oshiki et al. 2011), and the anammox process was likely limited by both nitrite and O2 but not by the ammonium concentration (Verhamme et al. 2011); this finding indicates that the nitrogen content is potentially irrelevant.

Suspects regarding nitrogen transformation

NH4+-N, NO2−-N and NO3−-N are important reactive substrates in N transformation. When nitrite, which is produced from nitrate denitrification, is inadequate in oxidizing NH4+-N, part of NH4+-N may be nitrified by O2 (Lai and Zhou 2010). However, the presence of excess nitrite could irreversibly inhibit nitrogen removal and restrict synthetization processes because of protein deficiency (Wang et al. 2016b). The accumulated nitrite might participate in the anammox process and be transformed into N2 (Engström et al. 2005). Previous research on the effects of functional gene groups on the N cycle transformation rate (Xu et al. 2018) found that the ammonia oxidation executed by amoA, anammox, and nitrite oxidoreductase (nxrA) contributed 93% to NH4+-N oxidation and 73% to nitrite; in addition, nxrA and nirS contributed 90% to denitrification. Anammox bacteria have been proven to contribute up to 50% of N2 production in marine sediments (Zhu et al. 2010). In mangrove sediments distributed along estuaries, the anammox process accounted for 57.5% of N2 production, and denitrification accounted for 30–58% in summer (Cao et al. 2017). Li’s study found that the ratio of anammox and denitrification in a lateral subsurface wetland was 0.75 to 0.9:1 (Li 2015). In this study, the NH4+-N/NO3−-N ratio at most sampling points ranged from nearly 1:3 to 2:3; at a few sampling sites, NH4+-N was higher than NO3−-N. However, in Zheng’s study in the Yangtze River Estuary (Zheng et al. 2014), NH4+-N was significantly higher than NO3−-N. The contrasting results in a similar study region indicate that the nitrogen content is dynamic and does not reflect the transformation process directly. Another study found that the gene abundance of archaeal amoA was closely correlated with potential nitrification rates (Zheng et al. 2014), which aligned with the lower potential nitrification rate in AOA compared with AOB in the ammonia oxidation process at most sampling sites in this study. In all sampling regions, the nirS gene was significantly richer than the hzsB gene; however, the anammox process was negligible in summer (Cao et al. 2017). Therefore, these research findings confirmed the point at which the nitrogen-transformation activities of the four microbes might coexist and react simultaneously.

Conclusion

In this study, the abundance, diversity, and distribution patterns of four nitrogen transformation-related microbes were determined along with salinity in the sediments of the Yangtze Estuary. The abundance and diversity of the nirS gene were the highest among all detected genes, whereas salinity seemed to have no correlation with the abundance. However, for AOB, it was adaptable to relatively higher salinity. As the correlated factor for AOB in this study, salinity promoted its abundance while restricting its diversity. In contrast, the resistance of archaeal characteristics allowed for the maintenance of the abundance and diversity and thus afforded strong adaptability regardless of the salinity gradients. Moreover, the spatial distribution patterns and dominant species of each microbial group varied and shifted along the sampling regions. When subjected to salinity gradients, a shift toward the distribution pattern and abundance of AOB was observed. Denitrifying microbes (nirS-type) were considered to interact with the other three microbial groups during nitrogen migration. In addition, based on the functions of identified dominant species and the nitrogen transformation in a previous study, four nitrogen transformation-related microbes were considered to coexist and might react simultaneously, which provided further insights regarding nitrogen transformation in the estuarine zone.

References

Awata T, Tanabe, K, Kindaichi, T, Ozaki, N, Ohashi, A (2012) Influence of temperature and salinity on microbial structure of marine anammox bacteria. Water Sci Technol 66: 958-964. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2012.234

Bai R, Chen X, He JZ, Shen JP, Zhang LM (2015) Candidatus Brocadia and Candidatus Kuenenia predominated in anammox bacterial community in selected Chinese paddy soils. J Soils Sediments 15: 1977-1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-015-1131-5

Baptista JD, Lunn M, Davenport RJ, Swan DL, Read LF, Brown MR, Morais C, Curtis TP (2014) Agreement between amoA gene-specific quantitative PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization in the measurement of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol 80: 5901-5910. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01383-14

Bernhard AE, Donn T, Giblin AE, Stahl DA (2005) Loss of diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria correlates with increasing salinity in an estuary system. Environ Microbiol 7: 1289-1297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00808.x

Biller SJ, Mosier AC, Wells GF, Francis CA (2012) Global biodiversity of aquatic ammonia-oxidizing archaea is partitioned by habitat. Front Microbiol 3: 252. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00252

Blainey PC, Mosier AC, Potanina A, Francis CA, Quake SR (2011) Genome of a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon determined by single-cell and metagenomic analysis. Plos One 6: e16626. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016626

Bowen JL, Valiela I (2001) The ecological effects of urbanization of coastal watersheds: historical increases in nitrogen loads and eutrophication of Waquoit Bay estuaries. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 58: 1489-1500. https://doi.org/10.1139/f01-094

Broda, E. (1977), Two kinds of lithotrophs missing in nature. Z Allg Mikrobiol 17: 491-493. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.19770170611

Cao W, Guan Q, Li Y, Wang M, Liu B (2017) The contribution of denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation to N2 production in mangrove sediments in Southeast China. J Soils Sediments 17: 1767-1776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-017-1653-0

Chain P, Lamerdin J, Larimer F, Regala W, Lao V, Land M, Hauser L, Hooper A, Klotz M, Norton J, Sayavedra-Soto L, Arciero D, Hommes N, Whittaker M, Arp D (2003). Complete genome sequence of the ammonia oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol 185: 2759-2773. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.185.21.6496.2003

Chen W, Chen K, Kuang C, Zhu DZ, He L, Mao X, Liang H, Song H (2016) Influence of sea level rise on saline water intrusion in the Yangtze River Estuary, China. Appl Ocean Res 54: 12-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2015.11.002

Church MJ, Wai B, Karl DM, DeLong EF (2010) Abundances of crenarchaeal amoA genes and transcripts in the Pacific Ocean. Environ Microbiol 12: 679-688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02108.x

Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, Marsh T, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM (2009) The ribosomal database project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D141-D145. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn879

Delgado-Baquerizo M, Maestre FT, Reich PB, Jeffries TC, Gaitan JJ, Encinar D, Berdugo M, Campbell CD, Singh BK (2016) Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature Commun 7: 10541. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10541

Deslippe JR, Jamali H, Jha N, Saggar S (2014) Denitrifier community size, structure and activity along a gradient of pasture to riparian soils. Soil Biol Biochem 71: 48-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.01.007

Ding S, Zheng P, Lu H, Chen J, Mahmood Q, Abbas G (2013) Ecological characteristics of anaerobic ammonia oxidizing bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97: 1841-1849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-013-4697-0

Engström P, Dalsgaard T, Hulth S, Aller RC (2005) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by nitrite (anammox): implications for N2 production in coastal marine sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Ac 69: 2057-2065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2004.09.032

Galloway, J N, Townsend, A R, Erisman, J W, Bekunda, M, Cai, Z, Freney, J R, et al. (2008) Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320: 889-892. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136674

Harhangi HR, Le MR, Van TA, Hu BL, Groen J, Kartal B, Tringe SG, Quan ZX, Jetten MS, Op HDC (2012) Hydrazine synthase, a unique phylomarker with which to study the presence and biodiversity of anammox bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 752-758. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.07113-11

He H, Zhen Y, Mi T, Fu L, Yu Z (2018) Ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria differentially contribute to ammonia oxidation in sediments from adjacent waters of Rushan Bay, China. Front Microbiol 9: 116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00116

He W, He Q, Zhou J (2015) Soil weathering-water environment-ecological risks in Hanjiang River Basin, China. Quatern Int 380-381: 297-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.017

Holland E A (1998) Nitrogen cycle. In: Geochemistry. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. Springer, Dordrecht.

Huang X, Hu B, Wang P, Chen X, Xu B (2016) Microbial diversity in lake–river ecotone of Poyang Lake, China. Environ Earth Sci 75: 965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5473-0

Jetten Mike SM Wagner M, Fuerst J, Mark van Loosdrecht, Kuenen JG, Strous M. (2001) Microbiology and application of the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process. Curr Opin Biotech 12: 283-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00211-1

Ji G, Wang R, Zhi W, Liu X, Kong Y, Tan Y (2012) Distribution patterns of denitrification functional genes and microbial floras in multimedia constructed wetlands. Ecol Eng 44: 179-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.03.015

Kim H, Bae HS, Reddy KR, Ogram A (2016) Distributions, abundances and activities of microbes associated with the nitrogen cycle in riparian and stream sediments of a river tributary. Water Res 106: 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.09.048

Kirwan ML, Megonigal JP (2013) Tidal wetland stability in the face of human impacts and sea-level rise. Nature 504: 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12856

Konneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA (2005) Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437: 543-546. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03911

Koops H-P, Böttcher B, Möller U, Pommerening-Röser A, Stehr G (1991). Classification of eight new species of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: Nitrosomonas communis sp. nov., Nitrosomonas ureae sp. nov., Nitrosomonas aestuarii sp. nov., Nitrosomonas marina sp. nov., Nitrosomonas nitrosa sp. nov., Nitrosomonas eutropha sp. nov., Nitrosomonas oligotropha sp. J Gen Microbiol 13:1689-1699. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-137-7-1689

Kuypers MMM. , Marchant HK, Kartal B (2018). The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:263-276. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9

Lai Y-L, Zhou S-Q (2010) Study on synergism characteristics of anammox and denitrification. China Water Wastewater

Lee JA, Francis CA (2017) Spatiotemporal characterization of San Francisco Bay denitrifying communities: a comparison of nirK and nirS diversity and abundance. Microb Ecol 73: 271-284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-016-0865-y

Lei Y , Zhu GB, Wang Yu, Feng XJ, Wang WD, Wang SY, Yin CQ (2011) Abundance and biodiversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in littoral wetland of Baiyangdian Lake, North China. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2:468-476. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1011.2011.00468

Li L-L (2015) Nitrogen removal pathways and microbial diversity in a hybrid constructed wetland. Dissertation, Chongqing University

Ligi T, Oopkaup K, Truu M, Preem J-K, Nõlvak H, Mitsch WJ, Mander Ü, Truu J (2014) Characterization of bacterial communities in soil and sediment of a created riverine wetland complex using high-throughput 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Ecol Eng 72: 56-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.09.007

Luria CM, Ducklow HW, Amaralzettler LA (2014) Marine bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotic diversity and community structure on the continental shelf of the western Antarctic Peninsula. Aquat Microb Ecol 73: 107-121. https://doi.org/10.3354/ame01703

Mao Y, Xia Y, Zhang T (2013) Characterization of Thauera-dominated hydrogen-oxidizing autotrophic denitrifying microbial communities by using high-throughput sequencing. Bioresour Technol 128: 703-710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.10.106

Miao L-Y, Wang X-A, Wang Z-G (2006) Studies on species diversity of Larix chinensis community ecotone. Frontiers of Biology in China 1:163–167

Mosier AC, Lund MB, Francis CA (2012) Ecophysiology of an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon adapted to low-salinity habitats. Microb Ecol 64: 955-963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-012-0075-1

Mulder A, van de Graaf AA, Robertson LA, Kuenen JG (1995) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation discovered in a denitrifying fluidized bed reactor. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 16: 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-6496(94)00081-7

Narita Y, Zhang L, Kimura ZI, Ali M, Fujii T, Okabe S (2017) Enrichment and physiological characterization of an anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium ‘Candidatus Brocadia sapporoensis’. Syst Appl Microbiol 40: 448-457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2017.07.004

Oshiki M, Shimokawa M, Fujii N, Satoh H, Okabe S (2011) Physiological characteristics of the anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium ‘Candidatus Brocadia sinica’. Microbiology 157: 1706-1713. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.048595-0

Oton EV, Quince C, Nicol GW, Prosser JI, Gubry-Rangin C (2016) Phylogenetic congruence and ecological coherence in terrestrial Thaumarchaeota. The ISME journal 10: 85-96. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.101

Reis MP, Avila MP, Keijzer RM, Barbosa FA, Chartone-Souza E, Nascimento AM, Laanbroek HJ (2015) The effect of human settlement on the abundance and community structure of ammonia oxidizers in tropical stream sediments. Front Microbiol 6: 898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00898

Schmid MC, Maas B, Dapena A, van de Pas-Schoonen K, van de Vossenberg J, Kartal B, van Niftrik L, Schmidt I, Cirpus I, Kuenen JG, Wagner M, Sinninghe Damste JS, Kuypers M, Revsbech NP, Mendez R, Jetten MS, Strous M (2005) Biomarkers for in situ detection of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 1677-1684. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.4.1677-1684.2005

Tourna M, Freitag TE, Nicol GW, Prosser JI (2008) Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environ Microbiol 10: 1357-1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01563.x

Trimmer M, Nicholls JC, Deflandre B (2003) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation measured in sediments along the Thames Estuary, United Kingdom. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 6447-6454. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.11.6447-6454.2003

Urakawa H, Tajima Y, Numata Y, Tsuneda S (2008) Low temperature decreases the phylogenetic diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in aquarium biofiltration systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 894-900. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01529-07

van de Vossenberg J et al. (2013) The metagenome of the marine anammox bacterium ‘Candidatus Scalindua profunda’ illustrates the versatility of this globally important nitrogen cycle bacterium. Environ Microbiol 15: 1275-1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02774.x

van der Star WR, Miclea AI, van Dongen UG, Muyzer G, Picioreanu C, van Loosdrecht MC (2008) The membrane bioreactor: a novel tool to grow anammox bacteria as free cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 101:286-294. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.21891

Verhamme DT, Prosser JI, Nicol GW (2011) Ammonia concentration determines differential growth of ammonia-oxidising archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. The ISME journal 5: 1067-1071. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.191

Wang M, Wang S, Long X, Zhuang L, Zhao X, Jia Z, Zhu G (2018) High contribution of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) to ammonia oxidation related to a potential active AOA species in various arable land soils. J Soils Sediments 19: 1077-1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-018-2108-y

Wang Q, Zhang L-M, Shen J-P, Du S, Han L-L, He J-Z (2016a) Nitrogen fertiliser-induced changes in N2O emissions are attributed more to ammonia-oxidising bacteria rather than archaea as revealed using 1-octyne and acetylene inhibitors in two arable soils. Biol Fert Soils 52: 1163-1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-016-1151-3

Wang Y, Ma X, Zhou S, Lin X, Ma B, Park HD, Yan Y (2016b): Expression of the nirS, hzsA, and hdh genes in response to nitrite shock and recovery in Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis. Environ Sci Technol 50: 6940-6947. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00546

Wang Y, Zhu G, Harhangi HR, Zhu B, Jetten MS, Yin C, Op den Camp HJ (2012) Co-occurrence and distribution of nitrite-dependent anaerobic ammonium and methane-oxidizing bacteria in a paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Lett 336:79-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02654.x

Wei Q, Kawagoshi Y, Huang X, Hong N, Van Duc L, Yamashita Y, Hama T (2016) Nitrogen removal properties in a continuous marine anammox bacteria reactor under rapid and extensive salinity changes. Chemosphere 148: 444-451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.041

Xing W, Li J, Li P, Wang C, Cao Y, Li D, Yang Y, Zhou J, Zuo J (2018) Effects of residual organics in municipal wastewater on hydrogenotrophic denitrifying microbial communities. J Environ Sci-China 65: 262-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2017.03.001

Xu H, Lin C, Chen W, Shen Z, Liu Z, Chen T, Wang Y, Li Y, Lu C, Luo J (2018): Effects of pipe material on nitrogen transformation, microbial communities and functional genes in raw water transportation. Water Res 143: 188-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.040

Xu S, Lu W, Mustafa MF, Caicedo LM, Guo H, Fu X, Wang H (2017) Co-existence of anaerobic ammonium oxidation bacteria and denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation bacteria in sewage sludge: community diversity and seasonal dynamics. Microb Ecol 74: 832-840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-017-1015-x

Yang J, Jiang H, Dong H, Hou W, Li G, Wu G (2015) Sedimentary archaeal amoA gene abundance reflects historic nutrient level and salinity fluctuations in Qinghai Lake, Tibetan Plateau. Sci Rep 5: 18071. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18071

Yin C, Fan F, Li Z, Song A, Zhu P, Peng C, Liang Y (2012) Influences of long-term application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on the composition and abundance of nirS-type denitrifiers in black soil. J Environ Sci-China 33: 3967-3975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-011-0280-z

Yoshie S, Noda N, Tsuneda S, Hirata A, Inamori Y (2004) Salinity decreases nitrite reductase gene diversity in denitrifying microbes of wastewater treatment systems. Appl Environ Microb 70: 3152-3157. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.5.3152-3157.2004

Yoshinaga I, Amano T, Yamagishi T, Okada K, Ueda S, Sako Y, Suwa Y (2011) Distribution and diversity of anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) bacteria in the sediment of a eutrophic freshwater lake, Lake Kitaura, Japan. Microbes Environ 26: 189-197. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME10184

Yu Z, Liu J, Li Y, Jin J, Liu X, Wang G (2018) Impact of land use, fertilization and seasonal variation on the abundance and diversity of nirS-type denitrifying bacterial communities in a Mollisol in Northeast China. Eur J Soil Biol 85: 4-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2017.12.001

Zehr JP, Ward BB (2002) Nitrogen cycling in the ocean: new perspectives on processes and paradigms. Appl Environ Microb. 68: 1015-1024. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.3.1015-1024.2002

Zhang Y, Chen L, Dai T, Tian J, Wen D (2015) The influence of salinity on the abundance, transcriptional activity, and diversity of AOA and AOB in an estuarine sediment: a microcosm study. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 99: 9825-9833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6804-x

Zheng L, Zhao X, Zhu G, Yang W, Xia C, Xu T (2017) Occurrence and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria from the surface to below the water table, in deep soil, and their contributions to nitrification. Microbiologyopen 6: e00488. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.488

Zheng Y, Hou L, Liu M, Gao J, Yin G, Li X, Deng F, Lin X, Jiang X, Chen F, Zong H, Zhou J (2015) Diversity, abundance, and distribution of nirS-harboring denitrifiers in intertidal sediments of the Yangtze Estuary. Microb Ecol 70: 30-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-0567-x

Zheng Y, Hou L, Liu M, Lu M, Zhao H, Yin G, Zhou J (2013) Diversity, abundance, and activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in Chongming eastern intertidal sediments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97: 8351-8363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4512-3

Zheng Y, Hou L, Newell S, Liu M, Zhou J, Zhao H, You L, Cheng X (2014) Community dynamics and activity of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in intertidal sediments of the Yangtze estuary. Appl Environ Microbiol 80: 408-419. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.03035-13

Zhi W, Ji G (2014) Quantitative response relationships between nitrogen transformation rates and nitrogen functional genes in a tidal flow constructed wetland under C/N ratio constraints. Water Res 64: 32-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.06.035

Zhou SQ (2006): Stoichiometric analysis of combined reaction of anaerobic ammonia oxidation with denitrification. Chinese J Anal Chem 34: 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1872-2040(06)60041-8

Zhou X, Li Y, Zhang J, Liu B, Wang M, Zhou Y, Lin Z, He Z (2016) Diversity, abundance and community structure of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in riparian sediment of Zhenjiang ancient canal. Ecol Eng 90: 447-458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.068

Zhou Z, Chen J, Meng H, Dvornyk V, Gu JD (2017) New PCR primers targeting hydrazine synthase and cytochrome c biogenesis proteins in anammox bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101: 1267-1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-8013-7

Zhou ZF, Zheng YM, Shen JP, Zhang LM, He JZ (2011) Response of denitrification genes nirS, nirK, and nosZ to irrigation water quality in a Chinese agricultural soil. Environ Sci Pollut R 18: 1644-1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-011-0482-8

Zhu G, Jetten MS, Kuschk P, Ettwig KF, Yin C (2010) Potential roles of anaerobic ammonium and methane oxidation in the nitrogen cycle of wetland ecosystems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86: 1043-1055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2451-4

Zhu G, Wang S, Li Y, Zhuang L, Zhao S, Wang C, Kuypers MMM, Jetten MSM, Zhu Y (2018) Microbial pathways for nitrogen loss in an upland soil. Environ Microbiol 20: 1723-1738. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14098

Zhu G, Wang S, Wang W, Wang Y, Zhou L, Jiang B, Op den Camp HJM, Risgaard-Petersen N, Schwark L, Peng Y, Hefting MM, Jetten MSM, Yin C (2013) Hotspots of anaerobic ammonium oxidation at land–freshwater interfaces. Nature Geosci 6: 103-107. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1683

Zhu G, Xia C, Shanyun W, Zhou L, Liu L, Zhao S (2015) Occurrence, activity and contribution of anammox in some freshwater extreme environments. Env Microbiol Rep 7: 961-969. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.1234

.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project (51509003/E090301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or laboratory animals.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to the work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Table S1 Information of sampling sites. Table S2 Specific DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification. Table S3 Values of environmental parameters. Table S4 Gene abundance of four functional genes. Fig. S1 Affiliation of AOA, AOB, anammox bacteria and denitrifying microbes on different levels at sampling region S1-S4. Fig. S2 Proportion of four microbial groups at sampling region S1-S4 on species level. Fig. S3 OTUs of four microbes in S1-S4. Number in the circle means the number of OTU. Numbers in red colored circle means the number of OTUs in sampling region S1. Numbers in green colored circle means the number of OTUs in sampling region S2. Numbers in blue colored circle means the number of OTUs in sampling region S3. And numbers in pink colored circle means the number of OTUs in sampling region S4. (DOCX 2358 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, L., Liu, T., Yuan, D. et al. Abundance, diversity, and distribution patterns along with the salinity of four nitrogen transformation-related microbes in the Yangtze Estuary. Ann Microbiol 70, 26 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13213-020-01561-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13213-020-01561-0