Abstract

Background

Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen-175 (PfEBA-175) is a candidate antigen for a blood-stage malaria vaccine, while various polymorphisms and dimorphism have prevented to development of effective vaccines based on this gene. This study aimed to investigate the dimorphism of PfEBA-175 on both the Bioko Island and continent of Equatorial Guinea, as well as the genetic polymorphism and natural selection of global PfEBA-175.

Methods

The allelic dimorphism of PfEBA-175 region II of 297 bloods samples from Equatorial Guinea in 2018 and 2019 were investigated by nested polymerase chain reaction and sequencing. Polymorphic characteristics and the effect of natural selection were analyzed using MEGA 7.0, DnaSP 6.0 and PopART programs. Protein function prediction of new amino acid mutation sites was performed using PolyPhen-2 and Foldx program.

Results

Both Bioko Island and Bata district populations, the frequency of the F-fragment was higher than that of the C-fragment of PfEBA-175 gene. The PfEBA-175 of Bioko Island and Bata district isolates showed a high degree of genetic variability and heterogeneity, with π values of 0.00407 & 0.00411 and Hd values of 0.958 & 0.976 for nucleotide diversity, respectively. The values of Tajima's D of PfEBA-175 on Bata district and Bioko Island were 0.56395 and − 0.27018, respectively. Globally, PfEBA-175 isolates from Asia were more diverse than those from Africa and South America, and genetic differentiation quantified by the fixation index between Asian and South American countries populations was significant (FST > 0.15, P < 0.05). A total of 310 global isolates clustered in 92 haplotypes, and only one cluster contained isolates from three continents. The mutations A34T, K109E, D278Y, K301N, L305V and D329N were predicted as probably damaging.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the dimorphism of F-fragment PfEBA-175 was remarkably predominant in the study area. The distribution patterns and genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 in Equatorial Guinea isolates were similar another region isolates. And the levels of recombination events suggested that natural selection and intragenic recombination might be the main drivers of genetic diversity in global PfEBA-175. These results have important reference value for the development of blood-stage malaria vaccine based on this antigen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria, a serious parasitic disease for public health that impacts the lives of millions of people worldwide and is responsible for half a million deaths annually [1]. Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium, which include five species that infect humans, of which Plasmodium falciparum has the highest mortality rate [2]. According to the World Malaria Report 2020, total of 229 million malaria cases were reported in 89 malaria endemic regions in 2019, and P. falciparum was responsible for approximately 99.7% of malaria cases in the Africa region [1]. Malaria is endemic in Equatorial Guinea, which is located in Central West Africa. Since 2004, the Bioko Island Malaria Control Project (BIMCP) has committed to reducing the burden of malaria on Bioko Island through methods, such as concerted vector control, improved case management, and various educational interventions for the past 15 years. As a result, the BIMCP has reduced malaria prevalence from 43.3% in 2004 to 10.5% in 2016 [3]. Similarly, some successes have been achieved in high-transmission areas in the world. However, malaria parasites with resistance to anti-malarial drugs and mosquito vectors with resistance to insecticides have highlighted the importance of developing a malaria vaccine [4]. Therefore, as a powerful tool for malaria control and prevention, an effective vaccine against malaria remains an important global health priority.

Vaccines are among the most successful and cost-effective interventions in the history of public health [5]. However, development an effective vaccine for P. falciparum malaria has been stymied by various issues, such as the extreme complexity of its biology, the diversity of genome organization, the capability of immune evasion and the intricate nature of infection cycle [6]. For instance, the invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasite involves many processes. Multiple interactions between host erythrocyte receptors and parasite ligands are displayed on the merozoite surface during the invasion process [7]. Hence, it is very important to develop a malaria vaccine against molecules which play critical roles in the invasion process into erythrocytes [4]. One of the major antigens of P. falciparum merozoite is PfEBA-175, a sialic acid-binding protein ligand, which was the first described invasion ligand of the parasite [8]. PfEBA-175 mainly interacts with glycophorin A located on the erythrocyte surface [9, 10]. The PfEBA-175 gene includes seven regions, and region II contains two cystine-rich segments (F1 and F2) responsible for binding to GPA [11]. It has been shown that immunization with PfEBA-region II could induce significant antiparasitic effects in vivo [12]. Studies have shown that PfEBA-175 region III has a highly dimorphic segment. The dimorphism of region III is an insertion of a 423 base pair segment in the FCR3 strain (F-fragment) or insertion of a 342 base pair segment in the CAMP strain (C-fragment) [8, 13, 14]. However, the relationship between the dimorphism of PfEBA-175 and host–parasite interactions is still unclear [15]. Several studies have indicated that the F or C segment binds to the GPA backbone after PfEBA-175 region II binds to GPA sialic acid residues [16, 17].

As an important P. falciparum vaccine candidate gene, PfEBA-175 has been found to show genetic polymorphisms between different isolates [18]. The aims of the present study were to investigate the genetic polymorphism of region II of PfEBA-175 gene of P. falciparum on Bioko and Bata, two districts of Equatorial Guinea, as well as to elucidate differences among global P. falciparum populations.

Methods

Study area and population

Equatorial Guinea is located on the west coast of Central Africa at approximately 3° N latitude and 9° E longitude. It is bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the west and south. This country consists of two parts: a mainland and an insular region (Fig. 1). Bioko is the largest island with a population of 335,048 inhabitants, which is located in the gulf of Guinea, 160 km northwest of the mainland region. Bata is the largest district in the mainland region, with a population of 244,264 inhabitants [19]. Despite the efforts made by the Equatorial Guinea Malaria Control Initiative (EGMCI, 2006–2011), and the Bioko Island Malaria Control Project (BIMCP, 2004–2018), which have had a marked impact on malaria transmission [20,21,22], malaria is still the major public health problem in the country (www.mcdinternational.org).

Ethical approval

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects or their parents, and this study and the consent process were approved by the Ethics Committee of Malabo Regional Hospital. The Ethical approval letter had been shown as Additional files 1 and 2.

Study population and blood sample collection

The study was carried out in Malabo Regional Hospital, private diagnostic clinics (PDCs) in different regions of Bioko Island and Bata district, and in a clinic of the Chinese medical aid team to the Republic of Equatorial Guinea. In 2018–2019, P. falciparum clinical samples (from individuals 4 months to 80 years of age) were collected from 297 P. falciparum malaria cases confirmed by microscopic examination and lateral flow test kit (ICT Diagnostics). Blood samples were collected on filter paper (Whatman 3 mm, GE Healthcare, Pittsburg, USA) for further molecular analysis, air-dried and stored in plastic sealing bags at ambient temperature. Thick blood smears were air dried and stained with 10% fresh Giemsa following standard procedures. After coding and recording the patient medical records, the dried blood filters were stored in plastic sealing bags at − 80 °C.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from the dried blood spots using 0.5% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) to free parasites from red blood cells followed by Chelex®100 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) method, as previously described [23], and stored at − 20 °C.

Allelic genotyping of the PfEBA-175

An improved nested PCR method for genotype determination of PfEBA-175 as described by Touré et al. [24] was used. In the first-round PCR, 1 μL of gDNA was amplified with 10 μL 2 × Taq Plus master Mix II (GenStar, Beijing, China), 1 μL of 10 μmol/L forward primer (EBA1: 5′-CAAGAAGCAGTTCCTGAGGAA-3′) and 1 μL of 10 μmol/L reverse primer (EBA2: 5′-TCTCAACATTCATATTAACAATTC-3′), and sterile ultrapure water was added to a final volume of 20 μL. Thermal cycling parameters for PCR were as follows: initial denaturation at 96 °C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 96 °C for 10 s, 57 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 50 s; and final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. For the second-round PCR, 1 μL of the primary PCR product was amplified with 10 μL 2 × Taq Plus master Mix II (GenStar, Beijing, China), 1 μL of 10 μmol/L forward primer (EBA3: 5′-GAGGAAAACACTGAAATAGCACAC-3′) and 1 μL of 10 μmol/L reverse primer (EBA4: 5′-CAATTCCTCC-AGACTGTTGAACAT-3′), and sterile ultrapure water was added to a final volume of 20 μL. The nested PCR cycling parameters used in the second round were the same as those used for the primary reaction. Nested PCRs were carried out using a LifeECO® PCR System 9700 (Bioer Technology, Binjiang District, China). An allele-specific positive control and DNA negative control were included in each set of reactions.

Detection of alleles of PfEBA-175

The PCR products were stained with StarGreen nucleic acid gel stain (GenStar, Beijing, China) and resolved by gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel. The fragment sizes were determined using a low molecular weight DNA ladder marker (250–5000 bp, Dongsheng Biotech, Guangzhou, China) and photographed with a Tanon 2500/2500R Gel Imaging System (Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Alleles of PfEBA-175 were categorized according to their molecular weights.

Amplification and sequencing of domains II and III of PfEBA-175

For sequencing domains II and III of PfEBA-175 gene, the samples were amplified by nested PCR. In the first-round PCR, 1 μL of gDNA was amplified with 10 μL PrimeSTAR Max Premix (Takara Bio, Dalian, China), 1 μL of 10 μmol/L forward primer (EBA175F1: 5′-ATTAACGCTGTACGTGTGTCTAG-3′) and 1 μL of 10 μmol/L reverse primer (EBA2: 5′-TCTCAACATTCATATTAACAATTC-3′), 1 μL of DMSO and sterile ultrapure water was added to a final volume of 20 μL. The thermal cycling parameters for PCR were as follows: initial denaturation at 96 °C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 96 °C for 15 s, 57.7 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 2 min; a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. For the second-round PCR, 1 μL of the primary PCR product was amplified with 10 μL PrimeSTAR Max Premix (Takara Bioko, Beijing, China), 1 μL of 10 μmol/L forward primer (EBA175F2: 5′-AAGAAATACTTCATCTAATAACG-3′) and 1 μL of 10 μmol/L reverse primer (EBA4: 5′-CAATTCCTCCAGACTGTTGAACAT-3′), and sterile ultrapure water was added to a final volume of 20 μL. The nested PCR cycling parameters of the second round were the same as those of the primary reaction. Nested PCRs were carried out using a LifeECO® PCR System 9700 (Bioer Technology, Binjiang District, China). All PCR products were analysed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Then, a random selection of 70 samples presented only one amplified fragment (F or C) were purified and then sequenced by using an ABI 3730 × L automated sequencer (BGI, Shenzhen, China). The sequencing primers were the same as the primers for the second-round PCR. All sequences were analysed and integrated by BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor Software version 7.2.5 (BioEdit, California, USA) and MEGA 7.0 [25] software.

Sequence analysis of domain II of the PfEBA-175

The MEGA 7.0 was used for the analysis of the nucleotide sequence polymorphism, and the amino acid sequences of domain II of PfEBA-175 from Equatorial Guinea were also analysed by this program. The numbers of segregating sites (S), haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (Hd), nucleotide diversity (π), and average number of pairwise nucleotide differences within a population (K) were estimated by using DnaSP 6.0 [26]. The value of π was calculated to estimate stepwise the diversity of domain II of PfEBA-175 based on a sliding window of 100 bp with a step size of 5 bp. Values of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions were estimated and compared using the Z test (P < 0.05 was considered significant) in the MEGA 7.0 program based on the method of Nei and Gojobori [27] with Jukes and Cantor correction. Tajima’s D value [28] and Fu and Li’s D and F values [29] were analysed using DnaSP 6.0 to evaluate the neutral theory of evolution [26]. Recombination parameters (R), which included the effective population size and probability of recombination between adjacent nucleotides per generation, and the minimum number of recombination events (Rm) were analyzed by DnaSP 6.0. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between different polymorphic sites was computed based on the R2 index using DnaSP 6.0. The nucleotide sequences obtained were aligned and translated into putative amino acid sequences using MEGA 7.0. To examine the phylogenetic relations among 310 PfEBA-175 region II of global P. falciparum isolates a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed. To obtain the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree, the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, applying the nucleotide substitution type and Poisson model and bootstrapping procedure with a minimum of 1000 bootstraps by using MEGA 7.0. The phylogenetic tree was further edited by iTol (https://itol.embl.de/).

Global sequences acquisition and global diversity analysis

The genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 domain II in other global P. falciparum isolates was analysed. Parasite populations from seven countries, including Kenya (n = 39, DQ092087–DQ092125), Thailand (Year = 2006, n = 48, DQ092039–DQ092086), Thailand (Year = 2015, n = 32, LC008232–LC008263), Benin (n = 8, KJ419497–KJ419504), Colombia (n = 20, KJ419512–KJ419531), Madagascar (n = 7, KJ419505–KJ419511), Peru (n = 30, KJ419547–KJ419576), Venezuela (n = 9, KJ419577–KJ419585), Nigeria (n = 30, AJ438799–AJ438828) and two regions of French Guiana, namely French Guiana (Camopi) (n = 23, KJ419586–KJ419608) and French Guiana (Maripasoula) (n = 15, KJ419532–KJ419546) were included in this analysis. All publicly available sequences covered the domain II of PfEBA-175 (The alignment of all genetic sequences used in the study with FASTA format as Additional file 3 showed). Nucleotide sequence polymorphism analysis and neutrality test were performed for each population using programs DnaSP 6.0 and MEGA 7.0 as described above. Genetic differentiation among parasite populations was calculated based on the fixation index (FST) to estimate pairwise DNA sequence diversity between and within populations using Arlequin 3.5 [30]. To investigate relationships among PfEBA-175 haplotypes, the haplotype network for a total of 310 PfEBA-175 sequences, including 49 Bioko Island and Bata district sequences and the 261 publicly available sequences from Kenya, Thailand, Benin, Colombia, Madagascar, French Guiana, Peru, Venezuela, and Nigeria, was constructed using the Median Joining algorithm of the PopART program [31]. Nucleotide diversity and natural selection of each region were analysed using DnasP 6.0 as described above.

Prediction of the impact of amino acid change upon protein structure

The potential impact of amino acid substitutions on the structure or function was predicted by the PolyPhen-2 [32] online server and PROVEAN [33]. The FOLDX plugin [34] in YASARA [35] was used to predict the changes in free energy before and after the mutations: ΔΔG(change) = ΔG(mutation)–ΔG(wild-type). Generally, the ΔΔG (change) > 0 to indicate a destabilizing mutation and ΔΔG (change) < 0 to indicate a stabilizing mutation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The chi-square test was used in the univariate analysis to compare proportions. Statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Dimorphism of the PfEBA-175 in Equatorial Guinea

Of the 297 blood samples extracted from the collections in Bioko Island (n = 225) and Bata district (n = 72), 254 yielded suitable PfEBA-175 amplicons for allelic genotyping. As shown in Fig. 2, two types of fragments were identified in Bioko and Bata by nested PCR; one was 795 bp, corresponding to the F-fragment, and the other was 714 bp. The vast majority of the P. falciparum isolates presented only one amplified fragment with 87.8%, while both fragments were observed in approximately 12.2% of the isolates representing mixed infections (Table 1). The frequency of F-fragment PfEBA-175 in Bioko Island and Bata P. falciparum isolates were 71.92% and 56.86%, respectively (Table 1). It is worth noting that the F-fragment was more frequently detected in Bioko Island than on the continent (P = 0.024, χ2 test).

Sequencing for the region II in Equatorial Guinea PfEBA-175

Of the 69 blood samples from the collections in Bioko (31 samples including 20 F-type and 11 C-type) and Bata (38 samples including 26 F-type and 12 C-type), with suitable F-type or C-type PfEBA-175 amplicons for sequencing, finally, 49 (28 samples from Bioko with 17 F-type and 11 C-type; 21 samples from Bata with 14 F-type and 11 C-type) full-length monoclonal PfEBA-175 region II sequences (532–1932) were analysed in the study. These nucleotide sequences have been deposited at GenBank under Accession Numbers (MW691428–MW691476).

Genetic polymorphisms and natural selection of the region II in Equatorial Guinea PfEBA-175

The parameters associated with nucleotide diversity and natural selection were also evaluated on the region II of Equatorial Guinea PfEBA-175 (Table 2). The average number of pairwise nucleotide differences (K) values of whole region II (532–1932), F1 domain (532–1275) and F2 domain (1456–1932) were 5.700, 3.677 and 1.891 in Equatorial Guinea PfEBA-175, respectively. The haplotype diversity (Hd) for PfEBA-175 region II was 0.97 ± 0.013. This value of F1 domain (0.959 ± 0.012) was higher than for the F2 domain (0.700 ± 0.067). The π value of PfEBA-175 region II was 0.00409 ± 0.00023. The π values analysis of the F1 and F2 domains revealed that more nucleotide diversity was concentrated in the F1 domain. In order to examine whether natural selection has contributed to the generation of region II diversity in Equatorial Guinea P. falciparum populations, the value of dn/ds was estimated using the Nei and Gojobori method. The value of dn/ds for region II was 0.005, suggesting that balancing natural selection might have occurred in region II of the Equatorial Guinea P. falciparum populations. Considering high positive dn/ds values for the F1 domain (0.006), these regions might experience more pressure from balancing natural selection forces. The estimated Tajima’s D value of region II was 0.07177 (P > 0.10). When Tajima’s D value was analysed for each domain, the F1 domain (0.52076, P > 0.10) showed higher positive Tajima’s D values compared to the F2 domain (0.14802, P > 0.10).

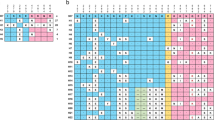

Amino acid polymorphism in PfEBA-175 region II from Equatorial Guinea and other global P. falciparum isolates

The amino acid polymorphisms of PfEBA-175 region II Equatorial Guinea isolates were compared to those from other countries or regions. The results showed that 24 amino acid changes were identified in PfEBA-175 region II from global isolates (Fig. 3, Table 3). There were 14 amino acid changes (A34T, K49E, E97K, I98K, K102E, K109E, E120K, D159Y, K211N, P213S, E226K, N227K, K228M, and N238S) that were found in the F1 domain in PfEBA-175 region II (Fig. 3, Table 3). Of the 9 amino acid changes (K301N, K304I, L305V, D329N, N400K, V402A, Q407K, Q407E, and E415A) were found in the F2 domain in PfEBA-175 region II (Fig. 3, Table 3), whereas D278Y exists in the linking region, which is between the F1 and F2 domain. The frequency of amino acid mutations of Equatorial Guinea P. falciparum isolates, whether from Bioko Island or Bata, is lower than that from other parts of the world. The most common amino acid changes is K102E, which frequency in the global isolates were as follows: Bioko (68.42%), Bata, (61.90%), Kenya (74.36%), Thailand (2006) (83.33%), Thailand (2015) (87.5%), Benin (100%), Madagascar (42.86%), Colombia (40%), French Guiana (Maripasoula) (60%), Peru (93.33%), Venezuela (77.78%), French Guiana (Camopi) (82.61%), and Nigeria (83.33%).

Furthermore, mutation effect prediction was conducted among these 24 sites. As shown in Table 3, the mutation D278Y was predicted to be deleterious using the PROVEAN program (score equal to or below − 2.5). According to the HumDiv score predicted by the PolyPhen-2 program, 6 amino acid changes were probably damaging. Among these probably damaging mutants, A34T, K109E, K301N, L305V, and D329N tended to destabilize the protein structure (ΔΔG > 0); D278Y was an exception to this pattern (Table 3). The PolyPhen-2 program was used to predict that the damaging mutation sites probably affect the structure and function of PfEBA-175 region II. The protein structural bioinformatics analysis indicated that these mutation sites were located in the corner area of PfEBA-175 region II (Fig. 4).

Nucleotide diversity and natural selection of PfEBA-175 region II in global P. falciparum isolates

Nucleotide diversity of PfEBA-175 region II in global isolates, including samples from Thailand, Colombia, French Guiana (Maripasoula), Peru, Venezuela, French Guiana (Camopi), Bata, Bioko, Kenya, Benin, Madagascar, and Nigeria, were analysed. K values of PfEBA-175 region II from Thailand isolates (Thailand 2006, K = 6.129 and Thailand 2015, K = 6.224) were higher than those from other geographical areas (Table 4). The nucleotide diversities of PfEBA-175 region II from different countries or regions were different by geographical area. The level of nucleotide diversity across the PfEBA-175 region II from Thailand, Bata and Madagascar P. falciparum isolates were similarly (Thailand 2006, π = 0.00437; Thailand 2015, π = 0.00444; Bata, π = 0.00411; Madagascar, π = 0.00411) were higher than from other global isolates (Table 4). A sliding window plot of the π values of PfEBA-175 region II from different geographical areas shows that their sequences have similar patterns of nucleotide diversity, and there are peaks in the F1 domain (Fig. 5a). Except for the isolates from the Bioko and French Guiana (Camopi), the sequences of PfEBA-175 regions II from other countries showed positive Tajima’s D values, which suggested a pattern of balancing selection across the majority of P. falciparum samples (Table 4). Additionally, the sliding window plot analysis showed that the sequences of global PfEBA-175 region II had different pattern in Tajima’s D among the different geographical origins (Fig. 5b).

Global nucleotide diversity and natural selection of PfEBA-175 region II. A Nucleotide diversity. Sliding window plot analysis shows the nucleotide diversity (π) value across PfEBA-175 region II from different countries. A window size of 100 bp and a step size of 5 bp were used. B Natural selection. Sliding window calculation of Tajima’s D statistic was performed for PfEBA-175 region II. A window size of 100 and a step size of 5 were used

Recombination and linkage disequilibrium

The minimum number of recombination events between adjacent polymorphic sites (Rm) of the PfEBA-175 region II from Bioko and Bata were estimated as 7 and 5, respectively (Table 5). The estimate of recombination parameter between adjacent sites (Ra) and per gene (Rb) of Bata isolates were, respectively, 0.0721 and 101, and were higher than those of other global isolates (Table 5). The lowest R values were predicted for the PfEBA-175 region II sequences from Colombia and French Guiana (Camopi). The LD index (R2) of global PfEBA-175 genes in the study decrease with increasing distance across this gene (Additional file 4).

Phylogenetic relations among PfEBA-175 region II

The phylogenetic relations among 310 PfEBA-175 region II of global P. falciparum isolates (Additional file 4) was assay by a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree. In the tree, P. falciparum isolated from Africa formed various clade rooted with Asia or South America P. falciparum isolated. But the P. falciparum isolated from Asia or South America P. falciparum isolated either formed a single clade rooted or formed a cluster with Africa P. falciparum isolated. And the P. falciparum isolated from Asia or South America was less correlation (Additional file 5), which may suggested different diversity pattern of these geographical areas.

Nucleotide differentiation among global PfEBA-175 region II

To assay the nucleotide differentiation of global PfEBA-175, the isolates from different geographical areas were evaluated using FST values (Table 6). FST values between different geographical PfEBA-175 populations varied from 0.00033 (P > 0.05) between Equatorial Guinea (Bioko) and Equatorial Guinea (Bata) to 0.44629 (P < 0.05) between French Guiana (Camopi) and Colombia, excluding negative values. Two negative values appeared in the FST analysis, which might due to the close geographical location of the sample source and the short sequence interval analysed in this study.

Haplotype network analysis

The haplotypes of PfEBA-175 from the global P. falciparum population analysed with the haplotype network showed a complex relationship-dense network (Fig. 6). A total of 92 haplotypes were identified in 310 PfEBA-175 sequences, of which 67.39% (62) were singletons. Haplotype prevalence ranged from 0.32 to 13.14%. The most prevalent haplotype was haplotype 6 (H_6), with a frequency of 13.14%. H_2, H_24, H_35, H_52, and H_82 were other major haplotypes with a high prevalence (3.21 to 12.82%). Only haplotype 6 contained haplotypes from three continents. H_2, H_3, H_13, H_22, H_24, H_35, H_37, H_59, and H_71 were composed of haplotypes from two continents (South American and African populations or African and Asian populations). Haplotypes from Equatorial Guinea (including Bioko Island and Bata district) were mostly scattered with no particular distribution pattern.

Discussion

Malaria monitoring and evaluation is of great significance for malaria control and assessment of the impact of intervention strategies. In addition, monitoring the genetic diversity of candidate vaccine antigens in global malaria isolates circulating in endemic areas is essential for designing an efficient and protective malaria vaccine [36]. This study provides an initial insight into the PfEBA-175 gene dimorphism of P. falciparum in Equatorial Guinea. In the assessment of the frequencies of the dimorphic allele of PfEBA-175 gene on P. falciparum merozoites, the F-fragment was predominated, which accounted for 56.86% and 71.92% of samples from Bata and Bioko, respectively, while the C-fragment was only 29.41% and 16.25%, respectively (Table 1). It is obvious that the F-fragment was observed at a higher frequency than the C-fragment. These findings are consistent with those of three independent research groups in geographic areas highly endemic for malaria in Burkina Faso [10], Ghana [13], and Gabon [37], where the F-fragment was also observed to be higher. In contrast, the study results from the Sudan [15] and Brazil [8] showed that the C-fragment was much higher. The different distributions of the F-fragment and C-fragment of PfEBA-175 in P. falciparum isolates among geographical areas may be due to random shifts in parasite allele frequencies in different geographic regions [13]. Interestingly, the C-fragment was most common in areas with a lower frequency of mixed infection. The previous study showed that geographic areas where higher F-fragment frequency was observed also had a higher frequency of mixed infections [10, 13, 37], and similar results were also found in the geographic areas of this study. At the same time, the study also revealed the genetic polymorphism and molecular evolution of region II of the PfEBA-175 gene of P. falciparum from Equatorial Guinea. The 49 sequences of PfEBA-175 region II from Equatorial Guinea populations (including Bioko Island and Bata district) compared to the PfEBA-175 region II of P. falciparum (Gene ID: XM_001349171.2) showed 20 different haplotypes. The results showed that the F1 domain had more mutations than the F2 domain. It was revealed that the sequence conservation was higher in the F2 domain than in the F1 domain, suggesting a greater selective pressure on the F2 domain, which is in accordance with the observation that binding is dependent on the F2 domain to a greater extent than the F1 domain [38]. Although the distribution patterns and genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 found in Bioko Island and Bata district were similar to those of other global isolates, several differences between them were identified in this study.

The π value of global PfEBA-175 isolates ranged from 0.00175 (Camopi of French Guiana) to 0.00444 (Thailand 2006) in the study. Among, the π value of PfEBA-175 isolates from Asia (isolates in Thailand collected in 2006 and 2015) were higher than those isolates from Africa and South America. In fact, the region II of PfEBA-175 is the largest target of the host’s immune system. The high number of genetic polymorphisms of PfEBA-175 region II from Bioko Island and Bata district indicated that these geographical areas are under the selection of host immune pressure during evolution. The previous study showed that IgG1 mouse monoclonal antibodies R217 and R218 recognize the F2 and F1 domains in PfEBA-175 region II, and a combination of R217 and R218 could block PfEBA-175 binding to erythrocytes and inhibit parasite growth [39, 40]. However, in this study, region II of PfEBA-175 showed high levels of polymorphism at the gene and amino acid levels, which were also found in the previous study [41], suggesting that the above region may affect vaccine effectiveness. Interestingly, the distribution patterns of nucleotide and amino acid diversity of PfEBA-175 isolates in this study indicated that PfEBA-175 may have similar genetic diversity across many endemic areas. The dn/ds value of PfEBA-175 region II of global isolates is positive (Table 4), suggesting the involvement of balancing selection. Except for the isolates from Bioko Island and French Guiana (Camopi), PfEBA-175 from most geographical areas had positive Tajima’s D values, indicating that the gene was under balancing selection in these areas. Additionally, the isolates from Bioko Island and French Guiana (Camopi) had similar patterns on the sliding plot analysis of Tajima’s D and showed differences from the PfEBA-175 of other isolates from other areas. The positive value of Tajima’s D for the PfEBA-175 gene indicated isolation with balancing selection, whereas the negative values in some populations can be interpreted as a signature of purifying selection or an expansion in the population size during recent parasite evolutionary history [42]. Similarly to the Tajima’s D values, the Fu and Li’s D and F values were positive in most areas, indicating balancing selection on the PfEBA-175 gene globally, except for Bioko Island and French Guiana (Camopi), where these values were negative. The recombination also contributes to the genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 under natural selection. This study revealed that PfEBA-175 isolates from Bioko Island have a high level of recombination, which is consistent with the previous study [41]. The high recombination level was found in the PfEBA-175 isolates from Bioko Island compared to other geographical areas, which may be attributed to the relatively independent environment of Bioko Island.

The FST value is an important parameter that was used to analysed the overall genetic differentiation. The results indicated that the FST values of PfEBA-175 isolates of Bioko Island had a lower level of genetic differentiation with isolates from Asia or Africa (Table 6). In addition, a moderate level of genetic differentiation was found between Bioko Island and South America, and similar results were found between Bata district and South America (Table 6). However, only lower levels of genetic differentiation were found between Bata district and Asia or Africa. In addition, the results indicated that FST values of PfEBA-175 populations from the same geographical areas were relatively low (Table 6). The negative values of FST, which were also found in the previous study of PfAMA-1 [43], may be attributed to the limited number of samples. Interestingly, the FST values of Bioko Island and Bata district with French Guiana (Camopi) were 0.34311 and 0.36412 (Table 6), which indicated geographical isolation in these areas. The average FST values of PfEBA-175 global isolates showed differently, which indicated that PfEBA-175 has genetic differentiation among the parasite populations of the world.

To assay the haplotype network of PfEBA-175 among the global isolates is important for developing an effective malaria vaccine based on this gene. In this study, 92 different haplotypes were identified from 310 PfEBA-175 sequences. Haplotype network analysis showed that the haplotypes of Bioko Island and Bata district were scattered among other haplotypes from different geographical areas, which was similar to the pattern found for another candidate vaccine gene, PfAMA-1 [43]. In this study, 26 of the 49 isolates from the haplotypes in Equatorial Guinea (including Bioko Island and Bata district) were shared with other isolates from Africa, Asia or South America, which suggested that the Bioko Island and Bata district PfEBA-175 isolates were not independent of other global isolates. On the other hand, there were 62 haplotypes that were limited to singletons (only observed in 1 sequence), which were found in the PfEBA-175 isolates from Africa (Bioko and Bata District 23, Kenya 11, Benin 1, Madagascar 4, Nigeria 8) and Asia (Thailand 15). This finding suggested that the PfEBA-175 of African isolates had higher genetic differentiation and provided an insight for the development of a vaccine based on PfEBA-175 in consideration of its diversity in different areas.

Conclusions

In this study, the frequencies of dimorphic alleles of PfEBA-175 gene on Bioko Island and in Bata district and the overall pattern of genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 from global isolates were analysed. There is no significant difference in the frequency of dimorphic alleles of the PfEBA-175 gene between the island and the mainland. The distribution patterns and genetic diversity of PfEBA-175 from global isolates showed that PfEBA-175 had a high genetic polymorphism. Compared with global PfEBA-175 isolates, high level of recombination events were observed on Bioko Island and in Bata district, suggesting that natural selection and intragenic recombination might be the main drivers of genetic diversity in global PfEBA-175. Additionally, the high level of nucleotide diversity and natural selection indicated that strong natural selection is occurring under host immune pressure during evolution. This study provides evidence for the continuous monitoring of PfEBA-175 nucleotide and amino acid changes of global P. falciparum isolates, and provides useful information for developing an effective malaria vaccine.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional files].

Abbreviations

- PfEBA-175:

-

Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocyte binding antigen-175

- MCDI:

-

Medical Care Development International

- BIMCP:

-

Bioko Island Malaria Control Project

- PDCs:

-

Private diagnostic clinics

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- Ra:

-

Recombination between adjacent sites

- Rb:

-

Recombination of per gene

- Rm:

-

The minimum number of recombination events

- FST:

-

Fixation Index

- PfAMA-1:

-

Plasmodium falciparum Apical membrane antigen-1

References

WHO: World malaria report 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791.

Weiss DJ, Lucas TCD, Nguyen M, Nandi AK, Bisanzio D, Battle KE, et al. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000–17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. The Lancet. 2019;394:322–31.

Cook J, Hergott D, Phiri W, Rivas MR, Bradley J, Segura L, et al. Trends in parasite prevalence following 13 years of malaria interventions on Bioko island, Equatorial Guinea: 2004–2016. Malar J. 2018;17:62.

Sakamoto H, Takeo S, Maier AG, Sattabongkot J, Cowman AF, Tsuboi T. Antibodies against a Plasmodium falciparum antigen PfMSPDBL1 inhibit merozoite invasion into human erythrocytes. Vaccine. 2012;30:1972–80.

Koff WC, Gust ID, Plotkin SA. Toward a human vaccines project. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:589–92.

Sack B, Kappe SH, Sather DN. Towards functional antibody-based vaccines to prevent pre-erythrocytic malaria infection. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:403–14.

Wanaguru M, Crosnier C, Johnson S, Rayner JC, Wright GJ. Biochemical analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen-175 (EBA175)-glycophorin-A interaction: implications for vaccine design. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32106–17.

Perce-da-Silva DS, Banic DM, Lima-Junior JC, Santos F, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, de Oliveira-Ferreira J, et al. Evaluation of allelic forms of the erythrocyte binding antigen 175 (EBA-175) in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Brazilian endemic area. Malar J. 2011;10:146.

Camus D, Hadley T. A Plasmodium falciparum antigen that binds to host erythrocytes and merozoites. Science. 1985;230:553–6.

Soulama I, Bougouma EC, Diarra A, Nebie I, Sirima SB. Low-high season variation in Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen 175 (eba-175) allelic forms in malaria endemic area of Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:51–9.

Singh SK, Hora R, Belrhali H, Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Structural basis for Duffy recognition by the malaria parasite Duffy-binding-like domain. Nature. 2005;439:741–4.

Jones TR, Narum DL, Gozalo AS, Aguiar J, Fuhrmann SR, Liang H, et al. Protection of Aotus monkeys by Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 region II DNA prime-protein boost immunization regimen. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:303–12.

Cramer JP, Mockenhaupt FP, Möhl I, Dittrich S, Dietz E, Otchwemah RN, et al. Allelic dimorphism of the erythocyte binding antigen-175 (eba-175) gene of Plasmodium falciparum and severe malaria: Significant association of the C-segment with fatal outcome in Ghanaian children. Malar J. 2004;3:11.

Binks RH, Baum J, Oduola AMJ, Arnot DE, Babiker HA, Kremsner PG, et al. Population genetic analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen-175 (eba-175) gene. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114:63–70.

Adam AAM, Amine AAA, Hassan DA, Omer WH, Nour BY, Jebakumar AZ, et al. Distribution of erythrocyte binding antigen 175 (EBA-175) gene dimorphic alleles in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Sudan. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:469.

Ware LA, Kain KC, Lee Sim BK, Haynes JD, Baird JK, Lanar DE. Two alleles of the 175-kilodalton Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;60:105–10.

Kain KC, Orlandi PA, Haynes JD, Sim KL, Lanar DE. Evidence for two-stage binding by the 175-kD erythrocyte binding antigen of Plasmodium falciparum. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1497–505.

Agwang C, Erume J, Okech B, Olobo J, Egwang TG. Age-dependent carriage of alleles and haplotypes of Plasmodium falciparum sera5, eba-175, and csp in a region of intense malaria transmission in Uganda. Malar J. 2020;19:361.

Gómez-Barroso D, García-Carrasco E, Herrador Z, Ncogo P, Romay-Barja M, Ondo Mangue ME, et al. Spatial clustering and risk factors of malaria infections in Bata district. Equatorial Guinea Malar J. 2017;16:146.

Kleinschmidt I, Torrez M, Schwabe C, Benavente L, Seocharan I, Jituboh D, et al. Factors influencing the effectiveness of malaria control in Bioko Island, equatorial Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:1027–32.

Kleinschmidt I, Schwabe C, Benavente L, Torrez M, Ridl FC, Segura JL, et al. Marked increase in child survival after four years of intensive malaria control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:882–8.

García GA, Hergott DEB, Phiri WP, Perry M, Smith J, Osa Nfumu JO, et al. Mapping and enumerating houses and households to support malaria control interventions on Bioko Island. Malar J. 2019;18:283–283.

Li J, Chen J, Xie D, Eyi UM, Matesa RA, Ondo Obono MM, et al. Limited artemisinin resistance-associated polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller and PfATPase6 gene isolated from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2016;6:54–9.

Touré FS, Mavoungou E, Me Ndong JM, Tshipamba P, Deloron P. Erythrocyte binding antigen (EBA-175) of Plasmodium falciparum: improved genotype determination by nested polymerase chain reaction. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:767–9.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302.

Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–26.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95.

Fu YX, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:693–709.

Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–7.

Leigh JW, Bryant D, Nakagawa S. Popart: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol Evol. 2015;6:1110–6.

Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–9.

Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46688.

Schymkowitz J, Borg J, Stricher F, Nys R, Rousseau F, Serrano L. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W382–8.

Krieger E, Vriend G. YASARA View-molecular graphics for all devices-from smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2981–2.

Volkman SK, Ndiaye D, Diakite M, Koita OA, Nwakanma D, Daniels RF, et al. Application of genomics to field investigations of malaria by the international centers of excellence for malaria research. Acta Trop. 2012;121:324–32.

Touré FS, Bisseye C, Mavoungou E. Imbalanced distribution of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 genotypes related to clinical status in children from Bakoumba. Gabon Clin Med Res. 2006;4:7–11.

Tolia NH, Enemark EJ, Sim BKL, Joshua-Tor L. Structural basis for the EBA-175 erythrocyte invasion pathway of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 2005;122:183–93.

Sim BK, Narum DL, Chattopadhyay R, Ahumada A, Haynes JD, Fuhrmann SR, et al. Delineation of stage specific expression of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 by biologically functional region II monoclonal antibodies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18393.

Smith J, Chen E, Paing MM, Salinas N, Sim BKL, Tolia NH. Structural and functional basis for inhibition of erythrocyte invasion by antibodies that target Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175. PLoS Path. 2013; 9.

Baum J, Thomas AW, Conway DJ. Evidence for diversifying selection on erythrocyte-binding antigens of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Genetics. 2003;163:1327–36.

Tajima F. The effect of change in population size on DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:597–601.

Wang YN, Lin M, Liang XY, Chen JT, Xie DD, Wang YL, et al. Natural selection and genetic diversity of domain I of Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen-1 on Bioko Island. Malar J. 2019;18:317.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Health of Guangdong Province and the Department of Aid to Foreign Countries of the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China for their help. The authors also thank Santiago-m Monte-Nguba for his technical help during the samples collection and diagnosis.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2019A1515110981); Key scientific research projects of Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (Grant Nos. 2019KTSCX101 and 2019GDXK0031); Guangxi Key Research and Development Foundation (Grant Nos. 2019JJD140052 and 2020JJA140656).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Field work was performed on Bioko Island and Bata district, EG. XZL and YEW conceived and designed the experiments. CSE, UME, DDX, JQH, HTM contributed the blood sample collection and diagnosis. Laboratory work was conducted at Chaozhou People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shantou University Medical College and Hanshan Normal University. PKY, XYL, ML, JTC, HYH, LYL, YZZ, HTM and XYC carried out molecular studies and performed statistical analysis. PKY, XYL, ML, YZZ and HYH collated data results and making tables and charts. PKY, XYL wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participants in the clinical study provided written informed consent before their enrolment, and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Malabo Regional Hospital, Bioko, Equatorial Guinea. All participants received adequate anti-malarial treatment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Ethical approval letter (Spanish version).

Additional file 2.

Ethical approval letter (Chinese version).

Additional file 3.

Recombination events of global PfEBA-175 genes.

Additional file 4.

Global PfEBA-175 region II acquired from NCBI and sequencing in the study.

Additional file 5.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of Global PfEBA-175 region II.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, PK., Liang, XY., Lin, M. et al. Population genetic analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen-175 (EBA-175) gene in Equatorial Guinea. Malar J 20, 374 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03904-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03904-x