Abstract

The Variscan basement of the Aiguilles-Rouges massif (Western Alps) exposes the Servoz syncline which consists of a metavolcano-sedimentary sequence composed of (i) a volcanic unit of unknown age and origin, (ii) Early Carboniferous sedimentary series affected by the Variscan orogeny and intruded by the Montées-Pélissier pluton, and (iii) a Late Carboniferous late-orogenic sedimentary sequence. We combined field investigations, Raman Spectroscopy on Carbonaceous Material geothermometry, and LA-ICPMS U-Th-Pb geochronology on zircon in order to reappraise the sedimentary sequence of the Servoz syncline. Our results allow us to identify three distinct sedimentary formations (F1, F2 and F3). The F1 formation is composed of metagreywackes, bimodal volcanic and magmatic rocks formed during basin opening at an early rifting stage (370–350 Ma) within a back-arc geodynamic setting. This extensional regime was responsible for a high thermal event recorded by a ca. 115 °C/km apparent geothermal gradient. Local anatexis of the basement rocks under the basin is dated at 351 ± 5 Ma. Basin inversion occurred between 350 and 330 Ma in response to oblique collision, with the development of large-scale dextral shear zones and syn-kinematic 340–330 Ma granite intrusions. Subsequent dextral transtension was responsible for the opening of a pull-apart basin between ca. 330 and 310 Ma with the deposition of the F2 phyllite formation that was later deformed by the ongoing dextral transcurrent Variscan tectonics at temperatures between 200 and 350 °C. Finally, the F3 terrigenous sedimentary rocks deposited at ca. 310–290 Ma in a late-orogenic extensional basin. The Alpine-related tectonic event overprinted all the temperatures below 350 °C. Although similar basins have been recognized in other External Crystalline Massifs of the Alps, the Servoz syncline is the first example that allows a major part of the polyphase tectonic evolution, since the early stages of the Devonian, to be recognized. Comparison with similar back-arc basins from the French Central massif, the Vosges massif and the Bohemian massif suggests that the External Crystalline Massifs initially belonged to the Moldanubian hinterlands of the Variscan belt.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Variscan orogen, which results from collision between the Laurussia and Gondwana supercontinents (e.g. Edel et al., 2018; Lardeaux et al., 2014; Martinez-Catalan et al., 2021; Matte, 1991), is associated with subduction of one or more oceanic domains during the Late Devonian – Early Carboniferous period (i.e. 380–350 Ma; Lardeaux et al., 2014; Franke et al., 2017; Paquette et al., 2017). This period of continental convergence generated contrasting tectonic and metamorphic processes in active margins and back-arc domains. The active margin of the northern edge of the Moldanubian zone (Variscan belt of Europe) experienced typical subduction-related high pressure–low temperature (HP–LT) metamorphic conditions (e.g. Ballèvre et al., 2003; Berger et al., 2010; Lotout et al., 2018; Massonne & Kopp, 2005; Schmädicke & Müller, 2000). This stage was followed by the collisional phase and the building of the orogenic plateau under Barrovian metamorphic conditions (e.g. Lardeaux et al., 2014; Martinez-Catalan et al., 2021; Schulmann et al., 2008). By contrast, the thermal evolution of the back-arc zone was controlled by Devonian–Carboniferous rifting during the earliest phase of the Laurussia–Gondwana convergence (Lardeaux et al., 2014), prior to the collision-related tectono-thermal event. The deposition of sedimentary and volcano-sedimentary rocks within the External Crystalline massifs (ECMs) of the Alps could be related to such supra-subduction opening of back-arc basins. However, this hypothesis remains speculative considering that (i) the syn- and late-orogenic basins described in other Variscan massifs show similarities with those occurring in the ECMs (e.g. Fréville et al., 2018; Guillot & Ménot, 2009), (ii) some microfossils from these basins indicate younger ages than the collision stage (Bellière & Streel, 1980) and (iii) the opening and geodynamic evolution of these basins are poorly constrained (e.g. Dobmeier et al., 1999), which prevents correlations with preserved basins in other Variscan massifs. Recently, it has been proposed that the ECMs belong to the Saxothuringian zone of the Variscan belt, rather than to the Moldanubian zone (Faure & Ferrière, 2022). Therefore, additional data on the early Variscan history of the ECMs are required to constrain their paleogeographic position in the Variscan belt and their geodynamic timing and thermal evolution.

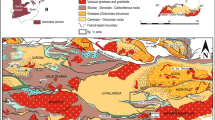

In this study, we focus on the Servoz syncline, located in the Aiguilles-Rouges massif (ARM) of the ECMs (Fig. 1A). It corresponds to a Late Devonian–Early Carboniferous basin infilled by metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks, deposited on a Proterozoic–Cambrian basement, and unconformably overlain by a Late Carboniferous formation (e.g. Bellière & Streel, 1980; Dobmeier, 1998; Dobmeier et al., 1999). Similar formations have been described in other ECMs (Fig. 1A) (e.g. Fréville et al., 2018, 2022; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Ménot, 1986, 1987), but their geodynamic interpretations vary from intracontinental rifting (e.g. Ménot, 1988; Ménot et al., 1988) to back-arc basins settings (e.g. Guillot et al., 2009; Pin & Carme, 1987). The tectonic significance and geodynamic setting of the Servoz syncline is still not well understood.

Based on U-Th-Pb geochronological data, Raman Spectroscopy on Carbonaceous Material (RSCM) geothermometry, and numerical modelling, we propose a new reconstruction of the early to post-orogenic thermal record of the Servoz basin. This thermal reconstruction suggests that the inversion of the Servoz basin, i.e. the transition from extension to collision, occurred under high heat-flow conditions, soon after the Devonian rifting stage. Our results open the Variscan geodynamic evolution of the ECMs for discussion and allow it to be correlated with similar formations from other nearby Variscan massifs.

2 Geological setting

2.1 The Aiguilles-Rouges massif and Alpine deformation

The Aiguilles-Rouges massif (ARM) is a 45-km-long NE trending Variscan massif bounded by (para)autochthonous and allochthonous Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks (Fig. 1). The ARM consists of basement composed of micaschists, paragneisses and Ordovician orthogneisses (Bussy et al., 2000), a Carboniferous basin (i.e. Servoz syncline; Figs. 1 and 2) (Bellière & Streel, 1980; Laurent, 1967) that may have opened during the Devonian (Dobmeier, 1996, 1998; Dobmeier et al., 1999) and a Late Carboniferous basin (Salvan-Dorenaz syncline; Fig. 1) (Capuzzo & Bussy, 2000).

A Map of the Servoz syncline, modified from Dobmeier (1996). B Synthetic stratigraphic Log of the Servoz syncline, modified from Pairis et al. (1992), Dobmeier (1996) and Dobmeier et al. (1999). Fossil occurrences are from Laurent (1967) and Bellière and Streel (1980). U–Pb Age of meta-igneous rocks are from Bussy et al. (2000) and Vanardois et al., (2022a, 2022b). AF: Arve Fault

Within the Variscan basement, the Alpine deformation is localized in low-grade shear zones (e.g. von Raumer & Bussy, 2004) developed under greenschist facies metamorphic conditions similar to those reported in the Mont-Blanc massif (e.g. Marshall et al., 1998; Rolland et al., 2003; Rossi et al., 2005). Alpine metamorphism in the surrounding autochthonous Mesozoic sedimentary rocks is limited to a temperature of about 300–400 °C (RSCM temperatures, Boutoux et al., 2016) (Fig. 1B). A single RSCM temperature on a Late Carboniferous sedimentary rock is reported in the Servoz area and yields a temperature of 343 ± 50 °C (Boutoux et al., 2016) (Fig. 1B). In the Late Carboniferous sedimentary rocks of the Servoz and Salvan-Dorenaz synclines, a non-pervasive vertical cleavage associated with open folds is attributed to Alpine deformation (Dobmeier & von Raumer, 1995; Lox & Bellière, 1993; Pilloud, 1991) (Fig. 1B).

2.2 Variscan tectono-metamorphic and magmatic evolution of the ARM

High-grade metamorphic rocks of the ARM basement record a clockwise P–T path, characterised by peak HP–HT conditions at ca. 340–330 Ma (Vanardois et al., 2022a), followed by two stages of decompression (Schulz & von Raumer, 1993, 2011; Vanardois et al., 2022a). Alternatively, Dobmeier (1998) documented a counterclockwise P–T evolution in paragneisses bordering the Servoz syncline and related it to a nappe-stacking event between 350 and 340 Ma. In the clockwise P–T evolution (Schulz & von Raumer, 1993, 2011; Vanardois et al., 2022a), decompression is accommodated by a horizontal flow D1 of the lower crust, associated with shallow dipping S1 foliations (Vanardois et al., 2022a), and by coeval dextral D2 transpressive shear zones forming both vertical S2 foliations and large-scale crustal shear zones striking from N330 to N030 (e.g. Bellière, 1958; Vanardois et al., 2022b; von Raumer & Bussy, 2004) (Fig. 2A). These transcurrent shear zones nucleated at ca. 340 Ma (Vanardois et al., 2022b) and were active until ca. 305–300 Ma (Simonetti et al., 2020; Vanardois et al., 2022b). The D2 transpressive shear zones affected both the Servoz basin and the basement (Vanardois et al., 2022b). Syn-kinematic plutons, such as the Montées-Pélissier and Pormenaz granites, emplaced between 340 and 330 Ma (Bussy et al., 2000; Vanardois et al., 2022b). A second Late Carboniferous magmatic pulse has been identified at 313–305 Ma with the emplacement of the Morcles and Vallorcine granites in the ARM, and the Mont-Blanc and Montenvers granites in the Mont-Blanc massif (MBM) (Bussy & von Raumer, 1993, 1994; Bussy et al., 2000; Vanardois et al., 2022b). These Late Carboniferous granites were emplaced through vertical dextral crustal-scale shear zones (Bussy et al., 2000; Dobmeier, 1998; Vanardois et al., 2022b). Finally, a third deformation (D3) consisting of a vertical shortening responsible for open folds and gently-dipping crenulation cleavage S3 has been described in the Servoz basin (Vanardois et al., 2022b). This fabric is usually discrete but can be locally pervasive, and even transposes the S2 foliation. The age of D3 deformation is likely Carboniferous, since it did not affect the late-orogenic Late Carboniferous–Permian sedimentary rocks (Pilloud, 1991; Vanardois et al., 2022b).

2.3 The Servoz syncline

The Servoz syncline is composed of a Devonian–Carboniferous volcanic and sedimentary series (Dobmeier, 1996, 1998; Dobmeier et al., 1999; Laurent, 1967) (Fig. 2). The bottom of the Servoz syncline series consists of volcanic rocks metamorphosed into epidote-bearing amphibolites and greenschists facies (Laurent, 1967) (Fig. 2B). In these volcanic rocks, SiO2 content varies from 44 wt% to 73 wt% with a predominance of andesitic compositions (Dobmeier et al., 1999). The major and trace element compositions define two magmatic suites corresponding to subduction-related magmas and continental tholeiite-type compositions (“Greenstones unit” from Dobmeier et al., 1999). The top of the series consists of phyllites and metagreywackes. These rocks contain quartz, white micas (sericite, muscovite and paragonite) and chlorite, with very rare detritic feldspar or biotite (Bellière & Streel, 1980). Based on the occurrence of continental microflora in the phyllites, Bellière and Streel (1980) proposed a Late Visean age for this formation. On the eastern side of the Servoz syncline, the Late Visean rocks are intruded by the Montées-Pélissier granite (Bussy et al., 2000; Dobmeier, 1996, 1998), which has been dated by U–Pb on zircon at 340 ± 5 Ma (LA-ICPMS, Vanardois et al., 2022b) and 332 ± 2 Ma (ID-TIMS, Bussy et al., 2000) (Fig. 2B). Empirically calibrated (Na, Ca)-amphibole–albite–chlorite–epidote–quartz geothermobarometer in the NaCaFMASH system (Triboulet, 1992) on epidote-bearing amphibolites yields P–T conditions of 0.32 GPa/445 °C and 0.67 GPa/630 °C in the eastern and western sides of the basin, respectively (Dobmeier, 1998). This difference in metamorphic conditions is attributed to the presence of a Variscan dextral shear zone, the Arve fault, located in the axial plane of the Servoz syncline which allowed the emplacement of the Montées-Pélissier granite (Bussy et al., 2000; Dobmeier et al., 1998) (Fig. 2A). However, the exact location of this fault remains enigmatic; it is either described in the eastern or western edge of the granite (Dobmeier, 1998; Pairis et al., 1992). 40Ar/39Ar muscovite dating of paragneisses from the basement yields ages of 337 ± 3 Ma and 331 ± 3 Ma on the west side and 316 ± 3 Ma on the east side of the Servoz syncline (Dobmeier, 1998). Using the garnet–biotite FeMg cation exchange geothermometer and garnet–plagioclase Ca-net-transfer geobarometer, the peak P–T conditions were estimated at 1.0 GPa/650 °C on the west side and 0.8 GPa/620 °C on the east side (Dobmeier, 1998 and references therein).

All these lithologies are unconformably overlain by a sequence of weakly deformed sandstones, shales and conglomerates (Dobmeier, 1996, 1998; Dobmeier & von Raumer, 1995; Lox & Bellière, 1983), whose age is estimated at the transition between Westphalian and Stephanian (i.e. Middle and Upper Pennsylvanian) based on fossil occurrences (Laurent, 1967) (Fig. 2B). These rocks are composed of detrital clasts of quartz, feldspar, muscovite and biotite coming from the eroded basement. In the Salvan-Dorenaz syncline (Fig. 1B), located in the northern part of the ARM, late-orogenic sedimentation similar to that of the Servoz syncline was dated by the U–Pb zircon method (ID-TIMS) on volcanic intercalations at 308–295 Ma (311–291 Ma if considering uncertainties; Capuzzo & Bussy, 2000). These sediments are interpreted as fluvial and alluvial fans deposits (Capuzzo & Wetzel, 2004).

3 Field observations and new lithostratigraphic subdivision

Based on both field observations and published data, we propose a new lithostratigraphic subdivision of the Servoz syncline sedimentary sequence (Fig. 2B), which overlies a metamorphic basement made of paragneisses, orthogneisses and partially molten amphibolites (Fig. 3A and B). The bottom of the stratigraphic sequence is composed of magmatic and volcano-sedimentary rocks metamorphosed into fine-grained gneisses (Fig. 3C), associated with metapelites (Fig. 3D) and rare dolomitic layers (Dobmeier et al., 1999). These lithologies form the ca. 3-km-thick ‘Pormenaz unit’ (Fig. 2) that is intruded by the Pormenaz granite dated at 338 ± 2 Ma (LA-ICPMS U–Pb on zircon; Vanardois et al., 2022b) and 332 ± 2 Ma (ID-TIMS U–Pb on zircon; Bussy et al., 2000). Upward, the ca. 1-km-thick metavolcanic rocks, named the ‘Forclaz unit’, underwent a lower metamorphic grade than the Pormenaz unit (Figs. 2 and 3E). Both the Forclaz and the Pormenaz units are derived from a bimodal magmatic suite ranging from acidic to mafic (Fig. 3G) compositions (Fig. 3F, G, Dobmeier et al., 1999). These metavolcanic rocks are overlaid by at least ca. 1.5 km of metagreywackes and phyllites (Fig. 3H, I) referred as the ‘Late Visean unit’, with a predominance of metagreywackes at the bottom and phyllites at the top (Laurent, 1967). A few layers of metaquartzites and meta-microconglomerates have been documented and are intercalated within the metagreywackes and phyllites (Dobmeier, 1996). The Montées-Pélissier granite intruded the metagreywackes of the Late Visean unit (Fig. 3H) (Bussy et al., 2000; Dobmeier, 1996, 1998) at 340–330 Ma (Bussy et al., 2000; Vanardois et al., 2022b) (Fig. 2). Microfloral analysis of the phyllites suggest a Late Visean deposition age (i.e.339–331 Ma) (Bellière & Streel, 1980) (Fig. 2B). These lithologies are unconformably covered by undeformed Upper Pennsylvanien—Early Permian (‘Kasimovian–Asselian unit’) sedimentary rocks (Figs. 2, 3J).

Typical lithologies from the SW part of the Aiguilles-Rouges massif. A Typical migmatitic paragneiss of the basement featuring vertical S2 foliations from the eastern of the Servoz syncline, near the Lac Cornu (45.963029; 6.855187). B Anatectic metavolcano-sedimentary rocks of the Pormenaz unit (AR982) from the western side of the Servoz syncline featuring shallowing dipping S1 foliations (45.865415; 6.734047). C Fine-grained gneiss from the Pormenaz unit in the Prarion area with S3 foliations folding S2 foliations (45.894366; 6.750432). D Micaschists from the Pormenaz unit featuring S2 foliations with relict S1 foliations, eastern side of the Servoz syncline near the Pormenaz granite (45.941785; 6.812287). E Metavolcanic rock from the Forclaz unit with vertical S2 foliations and F3 open folds, Prarion area, western side of the Servoz syncline (45.906418; 6.753869). F Acid (45.867327; 6.744562) and G mafic rocks (45.866916; 6.745102) from the bimodal magmatic suite from the Prarion area. H Intrusion of the Montées-Pélissier granite in Visean metagreywackes from the eastern side of the Servoz syncline (45.898301; 6.772357). I Visean phyllites and local metagreywacke layer featuring pervasive S3 foliations from the western side of the Servoz syncline, Prarion area (45.923449; 6.756683). J Kasimovian-Asselian conglomerate with mylonitic gneiss boulder, Pormenaz area (45.962838; 6.802037)

With the exception of the Kasimovian-Asselian unit, all units from the Servoz syncline are affected by the penetrative S2 and S3 planar fabrics described by Vanardois et al. (2022b), transposing stratigraphic beddings. On the other hand, the Kasimovian-Asselian unit is only weakly deformed: its bedding is only affected by a less penetrative planar fabric, probably Alpine in age. In addition, a local vertical, E-W striking S4 cleavage has been recognized in the western part of the Servoz syncline (Fig. 2A). The timing of S4 development and its tectonic significance remain unknown.

4 U-Th-Pb LA-ICPMS results

In order to further constrain the timing of sedimentation within the Servoz syncline, we performed U-Th-Pb Laser-Ablation Inductively-Coupled Plasma Mass-Spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) analyses on detrital zircon grains from a microconglomerate sample (AR476; GPS coordinates: 45.919727, 6.758245) of the upper structural levels of the Late Visean unit, and on zircon grains from a volcano-sedimentary rock (AR982; GPS coordinates: 45.871162, 6.740379) at the transition between the Pormenaz unit and the basement (Fig. 2B). Both samples are located in the western side of the Servoz syncline (see location on Figs. 1, 2).

Zircon crystals were separated using conventional mineral separation methods. The selected grains were mounted in epoxy resin and polished down to expose their near equatorial sections. Before analysis, cathodoluminescence (CL) images were acquired for each grain using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). LA-ICPMS spot locations were selected based on the internal microstructures and to avoid inclusions, fractures and physical defects. U-Th-Pb isotopic data were obtained at the Laboratoire Magmas & Volcans (LMV), Clermont-Ferrand, France. The detailed analytical procedures are described in Additional file 1 (Appendix A and Table S1). In the text, tables and figures, all uncertainties are given at 2σ level.

Discordant data analysed by the LA-ICPMS method are considered only if they allow for the definition of discordia lines in the concordia or/and Tera Wasserburg diagrams, so that the age(s) by intercept(s) have geological significance. Otherwise, the interpretation of the discordant data remains too doubtful. In LA-ICPMS analyses, several factors that are difficult to detect from the inspection of the time-resolved signals might contribute to discordance (e.g. common Pb, by way of inclusions, mixture of two components of distinct age, small cracks). Thus, discordant data are typically excluded from detrital datasets (Gehrels, 2012). In this study, we use single-analysis concordia ages (Ludwig, 1998) to highlight the concordance of our detrital zircon data.

4.1 Microconglomerate (AR476)

Sample AR476 is a microconglomerate from the upper structural levels of the phyllites within the Late Visean unit (Fig. 2B). In this area, the vertical S2 foliation is folded and transposed to S3 cleavage (Fig. 2A). It is composed of Qtz ± minor Kfs clasts embedded in a matrix made of white micas (probably Ms) + Qtz (abbreviations for mineral names are from Kretz (1983)). The sample is strongly altered. Micas define a S2 planar fabrics folded during the D3 event. Detrital zircon grains extracted from sample AR476 show various shapes, from rounded to sub-euhedral with elongated ratios between 3:1 and 1:1 (Fig. 4A). The analysed grains range in size from 100 to 300 µm. In CL, most crystals (e.g. Zr36, Zr18) are characterized by oscillatory zoning that probably reflects magmatic growth, but sometimes by faded oscillatory zoning (e.g. Zr 32). Moreover, a few crystals present core-rim relationships (e.g. Zr12, Zr56), with CL-bright cores with patchy or oscillatory zoning and featureless CL-dark rims (Fig. 4A). Due to the limited amount of zircon grains found, this study was performed on only 58 zircon grains (62 analyses). Most of the Th/U ratios are between 0.11 and 0.40, and only 13 values measured on rims or tips present a Th/U ratio less than 0.10 (Additional file 2: Table S2), typical for metamorphic zircon (e.g. Linnemann et al., 2011; Rubatto, 2017; Tiepel et al., 2004) (Fig. 4E). In the Tera Wasserburg diagram, most of the data are concordant (grey ellipses) and range from Neoproterozoic (Ediacarian) to Permo-Carboniferous ages with scattered concordant data at ca. 1 Ga, 875 Ma, 750 Ma and 660 Ma as well as one sub-concordant datum at ca. 1.8 Ga (Fig. 4B). Only data presenting a single-analysis concordia age, and single grain core-rim concordia age pairs giving distinguishable dates at 2σ, are considered and plotted in the histogram (Fig. 4C; Additional file 2: Table S2). For the period between the Ediacaran and Permian, the binned frequency histogram (coupled with a probability-density distribution) shows that at least 5 zircon crystallisation events were recorded around ca. 610–540 Ma, 500–460 Ma, 350–320 Ma and 320–290 Ma, with varying proportions of the aforementioned distinct events as well a few scattered date peaks at ca. 380 Ma and possibly at ca. 510 Ma and few Proterozoic dates (Fig. 4B and C). The Ediacaran date group is the most represented (n = 18) with a date peak around 570 Ma. This date has been obtained on zircon cores with oscillatory zoning and Th/U ratios higher than 0.17 (Fig. 4E). The early Palaeozoic dates fall into two similar-sized groups (n = 5 and 7) around 480 Ma and 440 Ma that are composed of rims and zoned cores with Th/U ratios between 0.10 and 0.40 for the Cambro-Ordovician date group and between 0.02 and 0.24 for the Ordo-Silurian date group (Fig. 4E). Finally, the Carboniferous dates also seem to be divided into two similar—sized groups (n = 4 and 5); one Visean (a date peak at ca. 335 Ma) and another Pennsylvanian (a date peak at ca. 310 Ma) (Fig. 4B). The Visean dates were mainly obtained on cores and rims characterized by Th/U ratios between 0.11 and 0.30 except for a datum at 0.02 obtained on a tip.

U–Pb LA-ICPMS results on the microconglomerate AR476. A Cathodoluminescence photos of zircons with locations of laser spots and associated single-grain concordia ages. B Zircon U–Pb Tera Wasserburg diagram. C Single-grain concordia ages histogram and probability distribution histogram were generated using a bin-width = 40 and a band-width = 10. Discordant ellipses (white ellipses) and concordant ellipses (grey ellipses) older than 650 Ma are not plotted in these diagrams. D Zoom-in of B on the youngest analyses. Only dark grey ellipses are used to calculate the concordia age. Error ellipses and uncertainties in ages are ± 2σ. € Zircon Th/U ratio vs. single-grain concordia age diagram. Th/U = 0.10 is the upper limit for metamorphic zircon after (1) and (2); 0.30 is the lower limit for the magmatic zircon after (2) and Th/U = 1 is the upper limit for the felsic zircon sources field after (3). (1): Rubatto, 2017; (2): Teipel et al. (2004) (3): Linnemann et al. (2011)

The youngest date cluster (date peak at ca. 310 Ma) consisting of 4 dates obtained on 3 tips/rims and one on a grain core, is characterized by Th/U ratios less than 0.10 and yields a concordia age at 307 ± 9 Ma (MSWD(C+E) = 3.1; n = 4) (Fig. 4D and E) and the youngest analysis has a single-analysis concordia age at 296.5 ± 8 Ma (Additional file 2: Table S2).

4.2 Prarion metavolcano-sedimentary rock (AR982)

Sample AR982, which is located in the southwestern edge of the ARM (Prarion area) (Fig. 1 and 2), is composed of Qtz + Amph + Bt + Pl + Kfs + Ttn (Fig. 5A, B) with an alternation of Amph + Ttn layers and Qtz + Kfs + Pl + Bt layers inherited from the volcano-sedimentary protolith. In this area, the presence of quartzo-feldspathic leucosomes showing small dihedral angles of interstitial phases (i.e. quartz and feldspar), quartz filling pores and elongated interstitial plagioclase grains indicate that the volcano-sedimentary rocks have undergone partial melting (Stuart et al., 2018) (Fig. 5B).

Description and U–Pb LA-ICPMS results on the Prarion metavolcano-sedimentary rock AR982. A Photo of the sample AR982 showing distinct Kfs-Pl-Qtz and Amph-rich layers. B Thin section images of the a Kfs-Pl-Qtz layer showing presence of small dihedral angles of interstitial phases (orange arrow), quartz filling pores (yellow arrows), and elongated interstitial plagioclases grains (blue arrow) that indicate a partial melting event (Lee et al., 2018; Stuart et al., 2018). Amph: amphibole; Bt: biotite; Kfs: K-feldspar; Pl: plagioclase; Ttn: titanites. C Cathodoluminescence photos of zircons with locations of laser spots and associated 206Pb/238U dates. D Zircon U–Pb Tera Wasserburg diagram. Dotted ellipses are not taken into account for the calculation of the weighted average of 206Pb/238U age of the two populations (grey and yellow ellipses) because they are affected by radiogenic Pb losses and/or common Pb contaminations. Error ellipses and uncertainties in ages are ± 2σ. E Diagrams of the weighted average 206Pb/238U age of the two populations (grey and yellow). Uncertainties in dates and ages are ± 2σ

Zircon grains from sample AR982 are pinkish and transparent to slightly opaque. They are euhedral with shape ratios between 2:1 and 3:1. CL imaging shows oscillatory igneous growth zoning as well as the presence of cores displaying either a sector-like zoning or patchy zoning textures surrounded by zoned or convolute rims (Fig. 5C). Forty-seven analyses were performed on rims or cores of 40 crystals (Fig. 5D, Additional file 2: Table S2). In the Tera Wasserburg diagram (Fig. 5D), the data are scattered between ca. 485 Ma and ca. 220 Ma; a subset of these forms two concordant clusters around ca. 475 Ma and 350 Ma. Amongst these data, fifteen analyses obtained on 10 cores (# 1, 7 13, 17, 20, 21, 40, 42, 43, 45) and 5 zoned tips (# 5, 10, 11, 19, 36) yield a weighted average 206Pb/238U date of 474 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 0.7) and present Th/U ratios ranging between 0.24 and 0.39 with variable Pb (14–75 ppm), U (182–969 ppm) and Th (54–361 ppm) contents (Fig. 5D and E, Additional file 2: Table S2). The other cluster is constituted by eight concordant data obtained on tips which are characterized by very low Th/U ratios (0.0–0.01) and low Th contents (1.9–8.7 ppm). The weighted average of 206Pb/238U dates is 351 ± 5 Ma (MSWD = 1.8) (Fig. 5D and E). In the diagram (Fig. 5D), the dotted ellipses are obtained mainly on the probably metamict tips which are characterized by very high U contents (most 651–2127 ppm). These data are not taken into consideration for the age calculation; their discordances are due to radiogenic Pb losses and common Pb contaminations.

5 RSCM geothermometry results

5.1 Thermometric approach and analytical method

Temperature is the key parameter that controls the structural evolution of natural carbonaceous material, which can be accurately assessed using Raman spectroscopy (e.g. Beyssac et al., 2002; Lahfid et al., 2010; Wopenka & Pasteris, 1993; Yui et al., 1996). Based on this approach, Raman Spectroscopy of Carbonaceous Material (RSCM) geothermometry can be used to estimate rocks’ maximum temperatures in the range 200–640 °C (Beyssac et al., 2002; Lahfid et al., 2010). In this study, all maximum temperatures determined by RSCM geothermometry, noted TRSCM, were estimated using the R2 parameter proposed by Beyssac et al. (2002). The R2 parameter represents the relative area of the main defect band, named D1 and located at 1350 cm−1 (see Beyssac et al., 2002 for details).

RSCM analyses were acquired at BRGM (Orléans, France) using a Renishaw inVia Reflex microspectrometer and following the analytical procedure outlined in Delchini et al. (2016). The Diode Pumped Solid State (DPSS) green laser was focused on the sample with power lower than 1 mW at the thin section surface through a × 100 objective (numerical aperture = 0.90) of a Leica DM2500 microscope. After interaction between the Carbonaceous Material (CM) and the laser beam, Raman signal was dispersed using 1800 lines/mm before being analyzed by a deep depletion Charge Coupled Device detector (1024 × 256 pixels). At least 15 spectra were recorded for each sample to ensure CM homogeneity. Both instrument calibration and RSCM measurements were performed using Renishaw Wire 4.1. Before each measurement session, the microspectrometer was calibrated using the 520.5 cm−1 line of internal silicon.

5.2 Raman spectra evolution

Raman spectra obtained on CM from metasedimentary rocks that experienced greenschist to amphibolitic facies metamorphic conditions (Pormenaz, metavolcanics, metagreywackes and phyllites from the Late Visean unit) show some spectral variations (Fig. 6). All spectra are mainly composed of a G band located at ~ 1580 cm−1 and defect bands D1 and D2 located at ~ 1350 cm−1 and ~ 1620 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 6B–E) but with differences in band parameters (e.g. relative intensity, area, full width at half maximum). The values of Raman parameter R2 (relative area of D1 band) of these samples vary between 0.20 and 0.65 (Table 1), corresponding to TRSCM between 550 and 350 °C (Fig. 6B to E), respectively.

A Map of the Servoz syncline with mean foliations and TRSCM temperatures, and B–E representative Raman spectra of carbonaceous material of four samples with varied temperatures. Colour of each sample is related to its TRSCM temperature. Cross-section of Fig. 7A is located. AF: Arve Fault

Raman spectra from Kasimovian–Asselian samples are similar to those observed for poorly ordered CM (e.g., Lahfid et al., 2010). They exhibit a broad composite G band located at ~ 1590 cm−1 (including the G band and the D2 band) and a very wide and more intense composite defect band around 1350 cm−1 (Fig. 6). The composite defect band includes D1 (around 1350 cm−1), D3 (around 1500 cm−1) and D4 (around 1200 cm−1) defect bands (Fig. 6). The values of Raman R2 vary between 0.60 and 0.67, corresponding to TRSCM between 340 and 360 °C (Table 1).

In the Pormenaz unit and metagreywackes from the Late Visean unit, the TRSCM are consistent with the temperatures obtained through the empirically calibrated (Na, Ca)-amphibole–albite–chlorite–epidote–quartz geothermobarometer on epidote-bearing amphibolites (Dobmeier, 1998), which gave temperatures at 620 ± 50 °C in the western side, and 450 ± 50 °C in the eastern side of the Arve fault (Fig. 6A). In the western side of the Arve fault, the TRSCM decrease from the bottom to the top of the sequence, whereas in the eastern side, TRSCM decrease toward the bottom of the sequence (Figs. 6 and 7A).

The TRSCM were plotted vs. the projected sample locations from the map along a SW-NE cross-section (Fig. 7A and B), considering the formation thicknesses. Two zones were determined on each side of the Arve fault, and two profiles are proposed (Fig. 7B). In the western side of the Arve fault, TRSCM measured in four samples collected in the Pormenaz unit and metagreywackes from the Late Visean unit vary from 400 to 550 °C and appear to define an abnormally high geothermal gradient of 115 ± 34 °C/km, (Figs. 6 and 7). In contrast, the 15 phyllite samples from the Late Visean unit yield constant TRSCM at ca. 350 °C (Fig. 7B-1).

In the eastern side of the Arve fault, metagreywackes samples from the Late Visean unit display TRSCM ranging from 530 to 420 °C and yield a poorly defined geothermal gradient of 30 ± 22 °C/km (Figs. 6 and 7). Profile (2) (Fig. 7B) shows that TRSCM from the metagreywackes from the Late Visean unit differs from the gradient defined in the western part and is reversed compared to the facing of the sedimentary sequence. The TRSCM measured in samples from the Kasimovian – Asselian unit are constant with temperatures of ca. 350 °C (Figs. 6 and 7).

6 Numerical modelling

RSCM data indicate an inverse thermal gradient in the eastern part of the Servoz syncline (Fig. 7). This inverse gradient could be induced by the emplacement of the Montées-Pélissier granite. In order to test this hypothesis, we performed numerical modelling of the thermal evolution of a metasedimentary sequence made of metagreywacke intruded by a vertical granitic intrusion. We use the heat equation:

where ρ is density (kg m−3), Cp is the heat capacity (J kg−1 K−1), T is the temperature (K), k is the thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) and H is the heat production (W m−3). Several studies on the thermal conductivity (k) as a function of temperature have demonstrated a strong temperature dependence of k (e.g. Vosteen & Schellschmidt, 2003; Whittinghton et al., 2009). In this study, we used the relationship proposed by Vosteen and Schellschmidt (2003) to model the variation of k as a function of the temperature for granitic and metasedimentary rocks. The thermo-dependent evolution of k is given by the following formulas:

with a = 0.0030 ± 0.0015 and b = 0.0042 ± 0.0006 for crystalline rocks (cry) and a = 0.0034 ± 0.0015 and b = 0.0039 ± 0.0014 for sedimentary rocks (sed) with k(0) being calculated for these rocks, respectively as:

The values of k(25) (Table 2) are from Vosteen and Schellschmidt (2003). The density (ρ) and the heat capacity (Cp) also vary as a function of the temperature but have a negligible effect on the temperature (e.g. Duprat-Oualid et al., 2015), thus typical fixed values were assigned (Table 2).

In Eq. (1), H corresponds to the heat production generated by radioactive decay. Possible additional heat sources (e.g. shear heating) are considered as negligible. Radiogenic heat production (A (µW m−3)) of the Montées-Pélissier granite was estimated by the relationship of Rybach (1998):

Concentrations, C, of U and Th in ppm and K2O in wt% are from Dobmeier (1996) and lead to a mean value of 4.0 µW m−3. Due to the absence of geochemical analyses on the metagreywackes, their radiogenic production was fixed at 1.0 µW m−3 (Hasterok et al., 2018) (Table 2).

The thermal gradient related to the granite intrusion was numerically modelled assuming an initial temperature of the granite of 700 °C and a thickness of 1 km. The intrusion was modelled in a four-kilometre-long horizontal 1D model, over 50 kyr, which is sufficient for most of the heat induced by the granite intrusion to be relaxed. The initial temperature of the metagreywackes (country rocks of the granite) cannot be higher than the TRSCM of sample AR807 given at 421 ± 17 °C (Fig. 6; Table 1). Therefore, initial surrounding temperature of the metagreywackes was fixed at 250 °C, 300 °C, 350 °C and 400 °C, respectively (Fig. 8). In these models, the 1-km thick granite sheet induces an inverse thermal gradient within a 50 ka time period (Fig. 8, see caption for coloured curves explanations). Considering an initial surrounding temperature of 250 °C, 300 °C and 350 °C, the modelled metagreywackes’ temperatures induced by the contact metamorphism are too low compared to the measured TRSCM (Fig. 8). However, with an initial temperature of at least 400 °C, the intrusion of the Montées-Pélissier granite produces contact metamorphism with temperatures fitting the observed TRSCM (Fig. 8).

Numerical models of the thermal diffusion of the Montées-Pélissier granite within metagreywackes at initial temperatures of 250, 300, 350 and 400 °C. Models last 50 kyr. Red lines: initial geotherms; Blue lines: geotherms every 5 ka. RSCM temperatures from the western side of the Servoz syncline are projected

7 Discussion

7.1 Time constraints on the deposition of the Servoz sediments

Since the study of Bellière & Streel (1980), two distinct stratigraphic units have been described in the Servoz syncline: the Late Visean unit (i.e. 339–331 Ma) and the Kasimovian–Asselian unit (i.e. 307–294 Ma) (e.g. Bellière & Streel, 1980; Dobmeier, 1996, 1998; Pairis et al., 1992). Based on palaeontological and geochronological data (including our new results), we propose that the Servoz syncline is ultimately composed of three main formations (F1, F2 and F3) (Fig. 9), as follows:

7.1.1 F1 formation (370–350 Ma)

The intrusion of the Montées-Pélissier granite in the metagreywackes of the Late Visean unit (dated at 340 ± 5 Ma) (Vanardois et al., 2022b), defines a minimum age for the deposition of the metagreywackes, and the deeper sedimentary and magmatic formations (i.e. Forclaz and Pormenaz units) (Figs. 2B and 9). The Rioupéroux-Livet formation described in the Belledonne and Pelvoux massifs, located about 100 km south of the study area, is composed of volcano-sedimentary rocks similar to the metavolcano-sedimentary rocks from the Pormenaz and Forclaz units (Dobmeier et al., 1999; Fréville et al., 2018, 2022; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Ménot, 1986). The Rioupéroux-Livet formation has been dated at ca. 370–350 Ma (U–Pb method on zircon, Fréville et al., 2018, 2022; Ménot et al., 1987). We propose that the emplacement of both the Forclaz and Pormenaz units is contemporaneous, i.e. between 370 and 350 Ma, and that the metagreywackes of the Late-Visean unit and the Forclaz and Pormenaz units belong to the same F1 formation (370–350 Ma).

Zircon U- Pb dating of the Prarion metavolcano-sedimentary sample (AR982) reveals two distinct populations (Fig. 5D): (1) an Ordovician population with a mean 206Pb/238U date at 474 ± 3 Ma obtained on cores and tips of zircon grains that are likely magmatic (Th/U > 0.1 and oscillatory zoning), and (2) a younger population with a mean 206Pb/238U date of 351 ± 5 Ma, defined by zircon tips with low Th contents (< 9 ppm) and very low Th/U ratios (0.0–0.01) indicating a metamorphic origin (e.g. Rubatto, 2017). The record of Ordovician magmatism in the ECMs is well documented (e.g. Bussy et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2021, 2022; Paquette et al., 1989; Rubatto et al., 2010; Schaltegger et al., 2003; Vanardois et al., 2022a, 2022b). We interpret the Ordovician date obtained on the Prarion metavolcano-sedimentary sample (AR982) as the emplacement age of the magmatic protolith. In contrast, the 351 ± 5 Ma date likely reflects the anatectic event affecting this area. This anatexis is consistent with elevated thermal conditions during the F1 formation and could therefore be synchronous with the bimodal magmatism.

7.1.2 F2 formation (330–310 Ma)

Based on micropaleontological data, Bellière and Streel (1980) proposed a Late Visean age (i.e. ca. 339–331 Ma) for the bottom phyllites from the Late-Visean unit (Fig. 9). Our U–Pb results achieved on detrital zircons from a microconglomerate (AR476), located at the top of the phyllites, emphasized a Visean population (ca. 335 Ma) mainly obtained on magmatic zircon. Given the proximal origin of these terrigenous sediments (Bellière & Streel, 1980), the source for these zircon grains may be represented by the Visean plutons such as the Pormenaz and/or Montées-Pélissier granites (Bussy et al., 2000; Vanardois et al., 2022b). This hypothesis implies that at least one of these plutons, and their country rocks (i.e. the F1 formation), were already exhumed and eroded during the phyllites sedimentation (F2 formation). A lateral change of exhumation rate could explain the difference of thickness of the metagreywackes between the western (ca. 500 m) and the eastern (ca. 1000 m) sides of the Servoz syncline (Fig. 7A). We propose that the metagreywackes and phyllites do not belong to the same continuous deposition event, and that the emplacement of the Montées-Pélissier granite within the F1 metagreywackes (dated at 340 ± 5 Ma and 332 ± 2 Ma; Bussy et al., 2000; Vanardois et al., 2022b), predates the deposition of the phyllites, giving an age at ~ 330 Ma for the beginning of the F2 sedimentary sequence.

Our geochronological results on detrital zircon grains also show the occurrence of an Upper Carboniferous population (ca. 310 Ma) that contains the youngest grain dated at 296.5 ± 8 Ma. The youngest age is generally used to infer a maximum limit for the deposition age (e.g. Bingen et al., 2001) as crystallization of the youngest detrital zircon predates the deposition of the host sediment. However, in some specific cases (i.e. Pb loss), this date may post-date the maximum depositional age, so the youngest detrital date is interpreted as the minimum of the maximum depositional age (Spencer et al., 2016). To ensure a statically more robust estimate of this data, the maximum age of deposition was calculated as the concordia age (Ludwig, 1998) of the youngest group of at least 3 grains with a 2σ (standard deviation) age overlap, as proposed by Dickinson and Gehrels (2009). For the microconglomerate (AR476), a concordia age of 307 ± 9 Ma (n = 4) was obtained, similar within error to the youngest detrital date (296.5 ± 8 Ma). This concordia age is interpreted as the maximum age of deposition. Sample AR476 displays an S3 foliation, which is absent in the Kasimovian–Asselian unit, suggesting that the investigated microconglomerate would most likely belong to the Late Visean unit (F2 formation). This observation implies that sedimentation of the F2 formation remained active until at least 307 ± 9 Ma. The unconformity existing between the Late-Visean unit (F2) and the Kasimovian–Asselian unit (F3) indicates an ante-Kasimovian deposition of F2 formation. Therefore, we propose that F2 formation was deposited between ca. 330 and 310 Ma.

7.1.3 F3 formation (310–295 Ma)

The F3 formation is composed of the Kasimovian–Asselian unit (Upper Pennsylvanian–Early Permian) that unconformably overlies F1 and F2 (Dobmeier, 1996, 1998; Pairis et al., 1992). The depositional age of the bottom of this formation has been estimated based on fossil flora at ca. 305 Ma (Laurent, 1967). In the Salvan-Dorenaz syncline, late-orogenic sedimentary rocks equivalent to the F3 formation have been documented (e.g. Capuzzo & Wetsel, 2004; von Raumer & Bussy, 2004), with a depositional age between ca. 308–295 Ma (Capuzzo & Bussy, 2000). Therefore, we propose a similar depositional age of ca. 310–295 Ma for the F3 late-orogenic sedimentary rocks (Fig. 9) of the Salvan-Dorenaz syncline (Fig. 9).

7.2 The trscm recorded in the Servoz syncline

In the western side of the Arve fault, TRSCM measured in F1 samples vary from 400 to 550 °C with a high thermal gradient of ca. 115 °C/km (Figs. 6 and 7). The high TRSCM obtained in the western Pormenaz unit (i.e. 550 ± 25 °C, sample AR447) is consistent within uncertainties with the 620 ± 50 °C temperature conditions obtained by thermobarometric analyses on amphiboles (Dobmeier, 1998). Even without considering the high TRSCM at 550 °C, the thermal gradient still remains higher than 50 °C/km. One may notice that the high-temperature isotherms in the ECMs are affected by Variscan dextral transpression (Simonetti et al., 2020; Vanardois et al., 2022b) and by several Alpine shear zones (Figs. 2, 7). Therefore, this abnormally high geothermal gradient is apparent and partially results from shortening related to Variscan and Alpine deformations.

In the eastern side of the Arve fault, metagreywacke samples from the F1 formation display TRSCM ranging from 530 to 420 °C (Figs. 6, 7) and may indicate an inverse gradient of ca. 30 °C/km. It is very likely that this abnormal gradient results from contact metamorphism associated to the Montées-Pélissier intrusion (ca. 340–330 Ma).

In the ECMs, peak temperatures within the F1 have been attributed to the early Variscan nappe stacking phase (Dobmeier, 1998; Fréville et al., 2018, 2022) ranging between ca. 350–340 Ma (Fréville et al., 2018; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Guillot et al., 2009), with a peak pressure dated at ca. 340–335 Ma (Jacob et al., 2021, 2022; Vanardois et al., 2022a). On the western side of the Arve fault, Dobmeier (1998) estimated maximum pressure conditions of 6.7 kbar. These pressure conditions are consistent with the peak temperatures estimated in the F1 formation assuming a geothermal gradient of ~ 30 °C/km. Considering the apparent high thermal gradient of ~ 115 °C/km estimated from TRSCM (Figs. 7B, 9), the initial thickness of the series would be four times greater than today (for a common geothermal gradient of ~ 30 °C/km). This important thickness reduction could result from both Variscan and Alpine deformations. However, our geochronological data on the partially molten Prarion volcano-sedimentary rock (AR982) highlight the presence of a metamorphic event, dated at 351 ± 5 Ma, that we link to a crustal anatectic episode. 40Ar/39Ar dating on muscovite (interpreted as cooling ages) from the basement gneisses on each side of the Servoz syncline yielded different results (i.e. 337–331 Ma for the west side and 316 Ma for the east side) (Dobmeier, 1998). These different cooling ages indicate that the basement from the western side of the Servoz syncline was at a shallow depth during Late-Visean, while the eastern side was still at HP–HT conditions (Schulz & von Raumer, 2011; Vanardois et al., 2022a). Thus, partial melting of the sample AR982 cannot be attributed to crustal thickening but rather to an early high-temperature thermal event. This early high-temperature thermal event was probably coeval with the bimodal magmatism forming the Pormenaz and Forclaz units during extensional tectonics (Dobmeier et al., 1999). Similar syn-extensional magmatism, dated between 370 and 350 Ma, has been described in the Belledonne and Pelvoux massifs (Fig. 1A) (Fréville et al., 2018; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Pin & Carme, 1987). Therefore, we propose that this high-temperature thermal event was inherited from an extensional setting dated at 370–350 Ma before crustal thickening in the ECMs.

Our numerical modelling indicates that, in the eastern part of the syncline, the temperature of the country rocks was above 400 °C at the time of the granite intrusion in order to fit the thermal conditions measured by TRSCM (Fig. 8). These results suggest that the F1 formation remained at temperature conditions around 400 °C from ca. 350 Ma to ca. 340 Ma during the granite emplacement (Vanardois et al., 2022b). Dobmeier (1998) calculated a peak pressure of 3.2 kbar in the eastern part of the Servoz syncline, which represents a depth of ~ 12 km. This depth and temperature are consistent with a thermal gradient of 30–35 °C/km. Dobmeier (1996, 1998) and Vanardois et al. (2022a) proposed that nappe stacking occurred before ca. 340 Ma. An extensional setting at ca. 350 Ma followed by a crustal thickening until ca. 340 Ma could explain the preservations of temperature conditions at 400 °C in the F1 formation, and also suggests the closure of the Servoz basin between 350 and 340 Ma.

From profiles (1) and (2), it appears that both F2 and F3 formations record the same maximum TRSCM at ca. 350 °C. Note that the 350 °C isotherm is recorded in the late-orogenic F3 rocks from the Servoz syncline and from one sample (AR853; Table 1) of the Salvan-Dorenaz syncline (Fig. 1B), indicating a post-Variscan origin. Similar TRSCM where measured in the surrounding Mesozoic rocks (Fig. 1B; Boutoux et al., 2016), emphasizing an Alpine origin for this thermal event probably related to the Tertiary nappe stacking (Boutoux et al., 2016; Girault et al., 2020). However, F2 phyllites were affected by the Variscan deformation (Figs 2A and 3I) (Bellière & Streel, 1980; Dobmeier, 1998; Vanardois et al., 2022b) responsible for the formation of a pervasive cleavage that can only develop with temperature conditions above 250–300 °C (e.g. Elliott, 1976). Therefore, we propose that F2 phyllites, which were affected by the Variscan orogeny at temperatures below 350 °C, were overprinted during the Alpine orogeny. Therefore, the three formations F1, F2 and F3 are defined by geochronological constrains also show distinct thermal evolutions.

7.3 Tectonic evolution of the Servoz syncline within the Variscan belt

7.3.1 Late Devonian – Early Carboniferous arc and back-arc settings in the Moldanubian zone

Our RSCM and geochronological data indicate that the F1 was deposited in an extensional setting (Fig. 10A). An extensional setting associated with the opening of basins and coeval with bimodal magmatism is also proposed in the Belledonne and Pelvoux massifs (Fréville et al., 2018; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Ménot, 1988; Ménot et al., 1988; Pin & Carme, 1987). However, these extensional basins and magmatic event have been interpreted as a syn-collisional continental rifting (Ménot, 1988; Ménot et al., 1988), a back-arc basin opening (Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Guillot et al., 2009; Pin & Carme, 1987), or the formation of an oceanic arc coeval with continental extension (Dobmeier et al., 1999). Several recent studies on the ECMs highlighted that crustal thickening started during Early Carboniferous times (e.g. Fréville et al., 2018, 2022; Jacob et al., 2021, 2022; Vanardois et al., 2022a), ruling out the scenario of Devonian syn-collisional continental rifting. In the Aar massif, Ruiz et al. (2022) recently dated a magmatic event at 348 Ma and interpreted it as a continental magmatic arc based on trace element and Hf isotope geochemistry. In the ARM, the assumption of Dobmeier et al. (1999) of a coeval oceanic arc with continental extension seems consistent with a back-arc setting.

Geodynamic evolution of the Servoz basin. A 370–350 Ma: Back-arc rifting induced a crustal thinning and a high heat mantle flux leading to the partial melting of the crust, the formation of a bimodal magmatism, and a high-thermal gradient in the metagreywackes forming the F1. B 350–330 Ma: Transpression during the continental collision inverted the basin and drained melts from the lower crust forming the Pormenaz (P) and Montées-Pélissier (MP) granites which induced contact metamorphism. C 330–310: The crustal dextral deformation formed a pull-apart basin in the western side of the Arve fault (AF) allowing the sedimentation of the F2 phyllites while the eastern side was exhumed. D 310–295 Ma: late-orogenic extension in a transtensional setting forming the late basins and the F3

Similar Late Devonian–Early Carboniferous basins associated with bimodal magmatism are described in the French Central massif (Faure et al., 1997; Pin & Paquette, 1998, 2002), Vosges massif (Pin, 1990; Pin & Carme, 1988; Skrzypek et al., 2012) and Bohemian massif (Schulmann et al., 2009; Žák et al., 2011). These volcanic basins are interpreted as back-arc basins related to the southward subduction of an oceanic domain located north of the Moldanubian zone (Lardeaux et al., 2014 and references therein). In South Corsica, Massonne et al. (2018) identified a high thermal gradient (45–50 °C/km) dated at 362 Ma. The authors related this gradient toa magmatic arc setting prior to continental collision. Similarly, Benmammar et al. (2020) argued that an anatectic event, dated at ca. 363 Ma and recorded within amphibolites from the southern French Central massif, correspond to an active continental margin setting, prior to continental collision. These data might indicate that during the Late Devonian – Early Carboniferous a large part of the Moldanubian zone was affected by high thermal conditions related to a magmatic arc and a back-arc setting, before the Carboniferous continental collision. This interpretation is consistent with recent paleogeographic reconstructions proposing the closure of one or several oceanic domains and basins during the Devonian before the Carboniferous collision (e.g. Deiller et al., 2021; Franke et al., 2017; Lardeaux et al., 2014; Neubauer et al., 2022).

Therefore, we interpret the 370–350 Ma basins of the ECMs as pre-collisional back-arc basins opened in response to the subduction of an oceanic domain beneath the Moldanubian domain then closed during the Early Carboniferous collision (Fig. 10B). These basins indicate that the ECMs were located in the Moldanubian zone, probably a few hundreds of kilometres away from the suture zone, somewhere between the French Central massif and the Bohemian massif. This interpretation contradicts the recent hypothesis of Faure and Ferrière (2022) that ascribed the ECMs to the Saxothuringian zone, except the western part of the Belledonne massif. These authors interpreted the greenschist-facies metamorphism of the western part of the Belledonne massif, as being incompatible with the high-grade metamorphism of the Moldanubian zone. However, the Carboniferous transcurrent tectonics in the ECMs juxtaposed domains of the upper and lower crust (Schulz & von Raumer, 1993, 2011; Vanardois, 2021) and thus the western part of the Belledonne massif may be a part of the upper Moldanubian crust that never experienced high-grade metamorphism.

7.3.2 Syn- and late-orogenic sedimentation controlled by transcurrent tectonics

The presence of F2 confirms that sedimentation was still active during and after the tectonic inversion. Recent studies propose that this period was dominated by a transpressive regime with the formation of several large vertical shear zones (Fréville et al., 2022; Simonetti et al., 2018, 2020, 2021; Vanardois et al., 2022b) either in the ECMs or throughout the Variscan belt (e.g. Ballèvre et al., 2018; Edel et al., 2018). In some places, these shear zones controlled the opening of intramountain pull-apart basins (e.g. Faure et al., 2005; Gumiaux et al., 2004; Shelley & Bossière, 2001). Several dextral strike-slip faults and shear zones affected the Servoz syncline, beginning prior the phyllite deposition and ending during the Late Carboniferous at ca. 305–300 Ma (Vanardois et al., 2022b). Therefore, we propose that the Servoz syncline was reactivated as a syn-orogenic pull-apart basin allowing the deposition of the F2 phyllites (Fig. 10C).

Finally, the opening of the late orogenic basins (F3) between 310 and 290 Ma is documented in the other ECMs (e.g. Guillot & Ménot, 2009) and also in the French Central massif (e.g. Faure, 1995; Faure et al., 2009). The late-orogenic opening of these Late Carboniferous basins in the ARM is emphasized by the presence of numerous gneissic and granitic boulders (Capuzzo et al., 2003) and a few syn-sedimentary normal faults (Pilloud, 1991) in the basins of the ARM, highlighting the erosion of relief and the opening and infilling of narrow intramountain basins (Capuzzo & Wetzel, 2004). The formation of these Late Carboniferous basins has been attributed to a late-orogenic collapse of the Variscan belt (Faure, 1995; Faure et al., 2009; Guillot & Ménot, 2009; Guillot et al., 2009). Alternatively, geochronological data from the ECMs may indicate that the dextral shearing was still active at least until 305–300 Ma (e.g. Bussy et al., 2000; Simonetti et al., 2020; Vanardois et al., 2022a). This dextral shearing evolved from a transpressional to transtensional regime (Vanardois et al., 2022b) and allowed the opening of these F3 basins (Fig. 10D). A similar evolution characterised by a change from a transpressional to a transtensional regime has been described in the southern French Central massif (e.g. Chardon et al., 2020; Whitney et al., 2015) and suggests that the late tectonics in the southern Variscan belt were controlled by the transcurrent shear zones rather than by a sensu stricto orogenic collapse.

8 Conclusion

Characterization of the thermal gradient and ages of sediment deposition and volcanic rocks from the Servoz syncline highlight a continuous record from pre-continental collision to post-orogenic evolution with three distinct sedimentary formations (F1, F2 and F3). The opening of the basin initiated between 370 and 350 Ma during an early stage of extensional tectonics triggered by a back-arc geodynamic setting. This extensional regime induced a high thermal gradient in the F1 metagreywackes associated with a bimodal magmatism. Subsequently, the rift basin was inverted during collision between 350 and 330 Ma. At that time, crustal thickening occurred in a global transpressional setting forming large-scale dextral shear zones that facilitated the emplacement of several plutons at ca. 340 Ma, inducing contact metamorphism as recorded in the sedimentary pile. In the Servoz syncline, dextral shearing controlled the opening of a pull-apart basin in the western part of the syncline during 330–310 Ma with the deposition of F2 phyllites formation. At the end of the Variscan orogeny, around 310–295 Ma, the F3 formation was deposited in a transtensional basin. The homogenization of peak temperatures at the scale of the Aiguilles-Rouges massif in both Carboniferous and Mesozoic rocks suggests that the Variscan thermal imprint of the F2 and F3 formations was later overprinted by Alpine metamorphism. The geodynamic evolution of the Servoz basins is consistent with the geodynamic evolution of the Moldanubian zone, suggesting a Moldanubian affiliation for the ECMs.

Availability of data and materials

All geochronological and Raman spectroscopy data produced for this paper are available in Additional files 1, 2, 3.

References

Ballevre, M., Pitra, P., & Bohn, M. (2003). Lawsonite growth in the epidote blueschists from the Ile de Groix (Armorican Massif, France): A potential geobarometer. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 21(7), 723–735.

Ballevre, M., Manzotti, P., & Dal Piaz, G. V. (2018). Pre-Alpine (Variscan) inheritance: A key for the location of the future Valaisan Basin (Western Alps). Tectonics, 37(3), 786–817.

Bellière, J. (1958). Contribution à l’étude pétrogénétique des schistes cristallins du massif des Aiguilles Rouges (Haute-Savoie). Annales De La Société Géologique De Belgique, Tome, 81, 209.

Belliere, J., & Streel, M. (1980). Roche d’âge Viséen Supérieur dans le Massif des Aiguilles Rouges (Haute-Savoie) Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences. Sciences Naturelles, 290(21), 1341–1343.

Benmammar, A., Berger, J., Triantafyllou, A., Duchene, S., Bendaoud, A., Baele, J. M., & Diot, H. (2020). Pressure-temperature conditions and significance of Upper Devonian eclogite and amphibolite facies metamorphisms in southern French Massif central. Bulletin De La Société Géologique De France, 191(1), 21.

Berger, J., Féménias, O., Ohnenstetter, D., Bruguier, O., Plissart, G., Mercier, J. C. C., & Demaiffe, D. (2010). New occurrence of UHP eclogites in Limousin (French Massif Central): Age, tectonic setting and fluid–rock interactions. Lithos, 118(3–4), 365–382.

Beyssac, O., Rouzaud, J. N., Goffe, B., Brunet, F., & Chopin, C. (2002). Graphitization in a high-pressure, low-temperature metamorphic gradient: A Raman microspectroscopy and HRTEM study. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 143(1), 19–31.

Bingen, B., Austrheim, H., & Whitehouse, M. (2001). Ilmenite as a source for zirconium during high-grade metamorphism? Textural evidence from the Caledonides of Western Norway and implications for zircon geochronology. Journal of Petrology, 42(2), 355–375.

Boutoux, A., Bellahsen, N., Nanni, U., Pik, R., Verlaguet, A., Rolland, Y., & Lacombe, O. (2016). Thermal and structural evolution of the external Western Alps: Insights from (U–Th–Sm)/He thermochronology and RSCM thermometry in the Aiguilles Rouges/Mont Blanc massifs. Tectonophysics, 683, 109–123.

Bussy, F., & Von Raumer, J. (1993). U-Pb dating of Palaeozoic events in the Mont-Blanc crystalline massif. Western Alps. Terra Nova, 5(1), 56–57.

Bussy, F., & Von Raumer, J. F. (1994). U-Pb geochronology of Palaeozoic magmatic events in the Mont-Blanc Crystalline Massif, Western Alps. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 74, 514–515.

Bussy, F., Hernandez, J., & Von Raumer, J. (2000). Bimodal magmatism as a consequence of the post-collisional readjustment of the thickened Variscan continental lithosphere (Aiguilles Rouges-Mont Blanc Massifs, Western Alps). Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 91(1–2), 221–233.

Bussy, F., Péronnet, V., Ulianov, A., Epard, J. L., & Von Raumer, J. F. (2011). Ordovician magmatism in the external French Alps: Witness of a peri-Gondwanan active continental margin. Ordovician of the World, 14, 567–574.

Capuzzo, N., & Bussy, F. (2000). High-precision dating and origin of synsedimentary volcanism in the Late Carboniferous Salvan-Dorénaz basin (Aiguilles-Rouges Massif, Western Alps). Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 80, 147–167.

Capuzzo, N., Handler, R., Neubauer, F., & Wetzel, A. (2003). Post-collisional rapid exhumation and erosion during continental sedimentation: The example of the late Variscan Salvan-Dorénaz basin (Western Alps). International Journal of Earth Sciences, 92(3), 364–379.

Capuzzo, N., & Wetzel, A. (2004). Facies and basin architecture of the Late Carboniferous Salvan-Dorénaz continental basin (Western Alps, Switzerland/France). Sedimentology, 51(4), 675–697.

Chardon, D., Aretz, M., & Roques, D. (2020). Reappraisal of Variscan tectonics in the southern French Massif Central. Tectonophysics, 787, 228477.

Delchini, S., Lahfid, A., Plunder, A., & Michard, A. (2016). Applicability of the RSCM geothermometry approach in a complex tectono-metamorphic context: The Jebilet massif case study (Variscan Belt, Morocco). Lithos, 256, 1–12.

Dickinson, W. R., & Gehrels, G. E. (2009). Use of U-Pb ages of detrital zircons to infer maximum depositional ages of strata: A test against a Colorado Plateau Mesozoic database. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 288(1–2), 115–125.

Deiller, P., Štípská, P., Ulrich, M., Schulmann, K., Collett, S., Peřestý, V., & Míková, J. (2021). Eclogite subduction wedge intruded by arc-type magma: The earliest record of Variscan arc in the Bohemian Massif. Gondwana Research, 99, 220–246.

Dobmeier, C. (1996). Die variskische Entwicklung des südwestlichen Aiguilles-Rouges-Massives (Westalpen, Frankreich). Mémoire De Géologie (lausanne), 29, 23.

Dobmeier, C. (1998). Variscan P-T deformation paths from the southwestern Aiguilles Rouges massif (External massif, western Alps) and their implication for its tectonic evolution. Geologische Rundschau, 87(1), 107–123.

Dobmeier, C., & Von Raumer, J. F. (1995). Significance of latest-variscan and alpine deformation for the evolution of montagne de pormenaz (southwestern aiguilles-rouges massif, western alps). Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 88(2), 267–279.

Dobmeier, C., Pfeifer, H. R., & Von Raumer, J. F. (1999). The newly defined" Greenstone Unit’’of the Aiguilles Rouges massif (western Alps): Remnant of an Early Palaeozoic oceanic island-arc? Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 79, 263–276.

Duprat-Oualid, S., Yamato, P., & Schmalholz, S. M. (2015). A dimensional analysis to quantify the thermal budget around lithospheric-scale shear zones. Terra Nova, 27(3), 163–168.

Edel, J. B., Schulmann, K., Lexa, O., & Lardeaux, J. M. (2018). Late Palaeozoic palaeomagnetic and tectonic constraints for amalgamation of Pangea supercontinent in the European Variscan belt. Earth-Science Reviews, 177, 589–612.

Elliott, D. (1976). A Discussion on natural strain and geological structure-The energy balance and deformation mechanisms of thrust sheets. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London., 283(1312), 289–312.

Faure, M. (1995). Late orogenic carboniferous extensions in the Variscan French Massif Central. Tectonics, 14(1), 132–153.

Faure, M., & Ferrière, J. (2022). Reconstructing the Variscan Terranes in the Alpine Basement: Facts and Arguments for an Alpidic Orocline. Geosciences, 12(2), 65.

Faure, M., Leloix, C., & Roig, J. Y. (1997). L’évolution polycyclique de la chaîne hercynienne. Bulletin De La Société Géologique De France, 168(6), 695–705.

Faure, M., Mézème, E. B., Duguet, M., Cartier, C., & Talbot, J. Y. (2005). Paleozoic tectonic evolution of medio-Europa from the example of the French Massif Central and Massif Armoricain. Journal of the Virtual Explorer, 19(5), 1–25.

Faure, M., Lardeaux, J. M., & Ledru, P. (2009). A review of the pre-Permian geology of the Variscan French Massif Central. Comptes Rendus Géoscience, 341(2–3), 202–213.

Franke, W., Cocks, L. R. M., & Torsvik, T. H. (2017). The palaeozoic variscan oceans revisited. Gondwana Research, 48, 257–284.

Fréville, K., Trap, P., Faure, M., Melleton, J., Li, X. H., Lin, W., & Poujol, M. (2018). Structural, metamorphic and geochronological insights on the Variscan evolution of the Alpine basement in the Belledonne Massif (France). Tectonophysics, 726, 14–42.

Fréville, K., Trap, P., Vanardois, J., Melleton, J., Faure, M., Bruguier, O., & Lach, P. (2022). Carboniferous tectono-metamorphic evolution of the Variscan crust in the Belledonne-Pelvoux area. Bulletin De La Société Géologique De France. https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2022008

Gehrels, G. (2012). Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology: Current methods and new opportunities. Tectonics of Sedimentary Basins: Recent Advances, 3, 45–62.

Girault, J. B., Bellahsen, N., Boutoux, A., Rosenberg, C. L., Nanni, U., Verlaguet, A., & Beyssac, O. (2020). The 3-D thermal structure of the Helvetic nappes of the European Alps: Implications for collisional processes. Tectonics, 39(3), 005334.

Guillot, S., & Ménot, R. P. (2009). Paleozoic evolution of the external crystalline massifs of the Western Alps. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 341(2–3), 253–265.

Guillot, S., di Paola, S., Ménot, R. P., Ledru, P., Spalla, M. I., Gosso, G., & Schwartz, S. (2009). Suture zones and importance of strike-slip faulting for Variscan geodynamic reconstructions of the External Crystalline Massifs of the western Alps. Bulletin De La Société Géologique De France, 180(6), 483–500.

Gumiaux, C., Gapais, D., Brun, J. P., Chantraine, J., & Ruffet, G. (2004). Tectonic history of the Hercynian Armorican shear belt (Brittany, France). Geodinamica Acta, 17(4), 289–307.

Hasterok, D., Gard, M., & Webb, J. (2018). On the radiogenic heat production of metamorphic, igneous, and sedimentary rocks. Geoscience Frontiers, 9(6), 1777–1794.

Jacob, J. B., Guillot, S., Rubatto, D., Janots, E., Melleton, J., & Faure, M. (2021). Carboniferous high-P metamorphism and deformation in the Belledonne Massif (Western Alps). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 39(8), 1009–1044.

Jacob, J. B., Janots, E., Guillot, S., Rubatto, D., Fréville, K., Melleton, J., & Faure, M. (2022). HT overprint of HP granulites in the Oisans-Pelvoux massif: Implications for the dynamics of the Variscan collision in the external western Alps. Lithos, 416, 106650.

Kretz, R. (1983). Symbols for Rock-Forming Minerals. American Mineralogist, 68(1–2), 277–279.

Lahfid, A., Beyssac, O., Deville, E., Negro, F., Chopin, C., & Goffé, B. (2010). Evolution of the Raman spectrum of carbonaceous material in low-grade metasediments of the Glarus Alps (Switzerland). Terra Nova, 22(5), 354–360.

Lardeaux, J. M., Schulmann, K., Faure, M., Janoušek, V., Lexa, O., Skrzypek, E., & Štípská, P. (2014). The moldanubian zone in the French Massif Central, Vosges/Schwarzwald and Bohemian Massif revisited: Differences and similarities. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 405(1), 7–44.

Laurent, R. (1967). Etude géologique et pétrographique de l’extrémité méridionale du massif des Aiguilles-Rouges (Haute-Savoie, France). Archives Des Sciences Genève, 20(2), 223–354.

Linnemann, U., Ouzegane, K., Drareni, A., Hofmann, M., Becker, S., Gärtner, A., & Sagawe, A. (2011). Sands of West Gondwana: An archive of secular magmatism and plate interactions—a case study from the Cambro-Ordovician section of the Tassili Ouan Ahaggar (Algerian Sahara) using U-Pb–LA-ICP-MS detrital zircon ages. Lithos, 123(1–4), 188–203.

Lotout, C., Pitra, P., Poujol, M., Anczkiewicz, R., & Van Den Driessche, J. (2018). Timing and duration of Variscan high-pressure metamorphism in the French Massif Central: A multimethod geochronological study from the Najac Massif. Lithos, 308, 381–394.

Lox, A., & Bellière, J. (1993). Le Silésien (Carbonifère supérieur) de Pormenaz (Massif des Aiguilles Rouges): Lithologie et tectonique. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 86(3), 769–783.

Ludwig, K. R. (1998). On the treatment of concordant uranium-lead ages. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 62(4), 665–676.

Marshall, D., Pfeifer, H. R., Hunziker, J. C., & Kirschner, D. (1998). A pressure-temperature-time path for the NE Mont-Blanc massif; fluid-inclusion, isotopic and thermobarometric evidence. European Journal of Mineralogy, 10(6), 1227–1240.

Martinez-Catalán, J. R., Schulmann, K., & Ghienne, J. F. (2021). The Mid-Variscan Allochthon: Keys from correlation, partial retrodeformation and plate-tectonic reconstruction to unlock the geometry of a non-cylindrical belt. Earth-Science Reviews, 220, 103700.

Massonne, H. J., & Kopp, J. (2005). A low-variance mineral assemblage with talc and phengite in an eclogite from the Saxonian Erzgebirge, Central Europe, and its P-T evolution. Journal of Petrology, 46(2), 355–375.

Massonne, H. J., Cruciani, G., Franceschelli, M., & Musumeci, G. (2018). Anticlockwise pressure–temperature paths record Variscan upper-plate exhumation: Example from micaschists of the Porto Vecchio region. Corsica. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 36(1), 55–77.

Matte, P. (1991). Accretionary history and crustal evolution of the Variscan belt in Western Europe. Tectonophysics, 196(3–4), 309–337.

Ménot, R. P. (1986). Les formations plutono-volcaniques dévoniennes de Rioupéroux-Livet (massifs cristallins externes des Alpes françaises): Nouvelles définitions lithostratigraphique et pétrographique. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 66(1–2), 229–258.

Ménot, R. P. (1987). Magmatismes paléozoiques et structuration carbonifère du Massif de Belledonne (Alpes Françaises). Contraintes nouvelles pour les schémas d'évolution de la chaîne varisque ouest-européenne. Mémoires et Documents du Centre Armoricain D'étude Structurale des Socles, 21.

Ménot, R. P. (1988). The geology of the Belledonne massif: An overview (External crystalline massifs of the western Alps). Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 68(3), 531–542.

Ménot, R. P., Bonhomme, M. G., & Vivier, G. (1987). Structuration tectono-métamorphique carbonifère dans le massif de Belledonne (Alpes Occidentales françaises), apport de la géochronologie K/Ar des amphiboles. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 67(3), 273–284.

Ménot, R. P., Peucat, J. J., & Paquette, J. L. (1988). Les associations magmatiques acide-basique paléozoïques et les complexes leptyno-amphiboliques: Les corrélations hasardeuses. Exemples du massif de Belledonne (Alpes occidentales). Bull Soc Géol Fr, 8, 917–926.

Neubauer, F., Liu, Y., Dong, Y., Chang, R., Genser, J., & Yuan, S. (2022). Pre-Alpine tectonic evolution of the Eastern Alps: From Prototethys to Paleotethys. Earth-Science Reviews, 226, 103923.

Paquette, J. L., Menot, R. P., & Peucat, J. J. (1989). REE, SmNd and UPb zircon study of eclogites from the Alpine External Massifs (Western Alps): Evidence for crustal contamination. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 96(1–2), 181–198.

Paquette, J. L., Ballèvre, M., Peucat, J. J., & Cornen, G. (2017). From opening to subduction of an oceanic domain constrained by LA-ICP-MS U-Pb zircon dating (Variscan belt, Southern Armorican Massif, France). Lithos, 294, 418–437.

Pairis, J.L., Bellière, J., Rosset, J. (1992). Notice de la carte géologique de la France, feuille Cluses (679), scale 1:50 000. Orléans : BRGM.

Pilloud, C. (1991). Structures de déformation alpines dans le synclinal de Permo-Carbonifère de Salvan-Dorénaz (massif des Aiguilles Rouges, Valais) (Doctoral dissertation, Université de Lausanne).

Pin, C. (1990). Variscan oceans: Ages, origins and geodynamic implications inferred from geochemical and radiometric data. Tectonophysics, 177(1–3), 215–227.

Pin, C., & Carme, F. (1987). A Sm-Nd isotopic study of 500 Ma old oceanic crust in the Variscan belt of Western Europe: The Chamrousse ophiolite complex, Western Alps (France). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 96(3), 406–413.

Pin, C., & Carme, F. (1988). Ecailles de matériaux d'origine océanique dans le charriage hercynien de la «Ligne des Klippes», Vosges méridionales (France). Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. Série 2, Mécanique, Physique, Chimie, Sciences de l'univers, Sciences de la Terre, 306(3), 217–222.

Pin, C., & Paquette, J. L. (1998). A mantle-derived bimodal suite in the Hercynian Belt: Nd isotope and trace element evidence for a subduction-related rift origin of the Late Devonian Brévenne metavolcanics, Massif Central (France). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 129(2), 222–238.

Pin, C., & Paquette, J. L. (2002). Sr-Nd isotope and trace element evidence for a Late Devonian active margin in northern Massif-Central (France). Geodinamica Acta, 15(1), 63–77.

Rolland, Y., Cox, S., Boullier, A. M., Pennacchioni, G., & Mancktelow, N. (2003). Rare earth and trace element mobility in mid-crustal shear zones: Insights from the Mont Blanc Massif (Western Alps). Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 214(1–2), 203–219.

Rossi, M., Rolland, Y., Vidal, O., & Cox, S. F. (2005). Geochemical variations and element transfer during shear-zone development and related episyenites at middle crust depths: Insights from the Mont Blanc granite (French—Italian Alps). Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 245(1), 373–396.

Rubatto, D. (2017). Zircon: The metamorphic mineral. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 83(1), 261–295.

Rubatto, D., Ferrando, S., Compagnoni, R., & Lombardo, B. (2010). Carboniferous high-pressure metamorphism of Ordovician protoliths in the Argentera Massif (Italy). Southern European Variscan Belt. Lithos, 116(1–2), 65–76.

Ruiz, M., Schaltegger, U., Gaynor, S. P., Chiaradia, M., Abrecht, J., Gisler, C., & Wiederkehr, M. (2022). Reassessing the intrusive tempo and magma genesis of the late Variscan Aar batholith: U-Pb geochronology, trace element and initial Hf isotope composition of zircon. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 115(1), 1–24.

Rybach, L. (1988). Determination of heat production rate. In R. Hänel, L. Rybach, & I. Stegena (Eds.), Terrestrial Handbook of Heat-flow Density Determination (pp. 125–142). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Schaltegger, U., Abrecht, J., & Corfu, F. (2003). The Ordovician orogeny in the Alpine basement: Constraints from geochronology and geochemistry in the Aar Massif (Central Alps). Swiss Bulletin of Mineralogy and Petrology, 83(2), 183–239.

Schmädicke, E., & Müller, W. F. (2000). Unusual exsolution phenomena in omphacite and partial replacement of phengite by phlogopite+ kyanite in an eclogite from the Erzgebirge. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 139(6), 629–642.

Schulmann, K., Lexa, O., Štípská, P., Racek, M., Tajčmanová, L., Konopásek, J., & Lehmann, J. (2008). Vertical extrusion and horizontal channel flow of orogenic lower crust: Key exhumation mechanisms in large hot orogens? Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 26(2), 273–297.

Schulmann, K., Konopásek, J., Janoušek, V., Lexa, O., Lardeaux, J. M., Edel, J. B., & Ulrich, S. (2009). An Andean type Palaeozoic convergence in the Bohemian massif. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 341(2–3), 266–286.

Schulz, B., & von Raumer, J. F. (1993). Syndeformational Uplift of Variscan High-pressure Rocks (Col de Bérard, Aiguilles Rouges Massif, Western Alps). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft, 104–120.

Schulz, B., & von Raumer, J. F. (2011). Discovery of Ordovician-Silurian metamorphic monazite in garnet metapelites of the Alpine External Aiguilles Rouges Massif. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 104(1), 67–79.

Shelley, D., & Bossière, G. (2001). The Ancenis Terrane: An exotic duplex in the Hercynian belt of Armorica, western France. Journal of Structural Geology, 23(10), 1597–1614.

Simonetti, M., Carosi, R., Montomoli, C., Langone, A., D’Addario, E., & Mammoliti, E. (2018). Kinematic and geochronological constraints on shear deformation in the Ferriere-Mollières shear zone (Argentera-Mercantour Massif, Western Alps): Implications for the evolution of the Southern European Variscan Belt. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 107(6), 2163–2189.

Simonetti, M., Carosi, R., Montomoli, C., Cottle, J. M., & Law, R. D. (2020). Transpressive deformation in the southern european variscan belt: new insights from the aiguilles rouges massif (Western Alps). Tectonics, 39(6), e2020CT006153.

Simonetti, M., Carosi, R., & Montomoli, C. (2021). Strain Softening in a Continental Shear Zone: A Field Guide to the Excursion in the Ferriere-Mollières Shear Zone (Argentera Massif, Western Alps, Italy). In Structural Geology and Tectonics Field Guidebook—Volume 1 (pp. 19–48). Springer, Cham.

Skrzypek, E., Tabaud, A. S., Edel, J. B., Schulmann, K., Cocherie, A., Guerrot, C., & Rossi, P. (2012). The significance of Late Devonian ophiolites in the Variscan orogen: A record from the Vosges Klippen Belt. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 101(4), 951–972.

Spencer, C. J., Kirkland, C. L., & Taylor, R. J. (2016). Strategies towards statistically robust interpretations of in situ U-Pb zircon geochronology. Geoscience Frontiers, 7(4), 581–589.

Stuart, C. A., Piazolo, S., & Daczko, N. R. (2018). The recognition of former melt flux through high-strain zones. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 36(8), 1049–1069.

Teipel, U., Eichhorn, R., Loth, G., Rohrmüller, J., Höll, R., & Kennedy, A. (2004). U-Pb SHRIMP and Nd isotopic data from the western Bohemian Massif (Bayerischer Wald, Germany): Implications for upper Vendian and lower Ordovician magmatism. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 93(5), 782–801.

Triboulet, C. (1992). The (Na–Ca) amphibole–albite–chlorite–epidote–quartz geothermobarometer in the system S-A–F–M–C–N–H2O. 1. An empirical calibration. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 10(4), 545–556.