Abstract

The current study examines how careless online behavior and personality traits are related to the detection of fake news. We tested the relationships among accurately distinguishing between fake and real news headlines, careless online behavioral tendencies, and the HEXACO and dark triad personality traits. Poorer discernment between fake and real news headlines was associated with greater careless behavior online (i.e., greater online disinhibition, greater risky online behavior, greater engagement with strangers online, and less suspicion of others’ intentions online), as well as lower Conscientiousness, Openness, and Honesty-Humility, and greater dark triad traits. Implications for the literature as well as potential interventions to reduce susceptibility to misinformation and fake news are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

The information environment is leveraged by adversaries, criminals, and individuals to spread fake news, conspiracy theories, disinformation, and misinformation.Footnote 1 Belief in conspiracy theories can increase during times of uncertainty, often to explain things that are out of one’s control (Douglas, 2021; Miller, 2020; van Prooijen and Acker, 2015). Amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, for example, conspiracy theories and misinformation about the spread, prevention, and severity of the disease proliferated (e.g., Douglas, 2021). Research shows that conspiratorial beliefs regarding medicine and health can have behavioral consequences. For example, holding conspiratorial beliefs about AIDS has been associated with reduced safer sex practices (Grebe and Nattrass, 2012). In addition, holding conspiratorial beliefs about birth control being a form of Black genocide reduced contraceptive use in African American respondents (Thorburn and Bogart, 2005). Further still, individuals who held more anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs, and those who were exposed to anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, were less likely to report intentions to vaccinate their children than those who did not (Jolley and Douglas, 2014). From the examples above, the uptake of false information can have real consequences on participation in public health measures like vaccine uptake, which has been a priority since COVID-19 vaccines became available. Endorsement of conspiracy theories about COVID-19 have even been associated with self-reported reduced participation, compliance (Earnshaw et al., 2020; Pummerer et al., 2022), and support for public health measures like handwashing, social distancing (Allington et al., 2020; Bierwiaczonek et al., 2020), mask-wearing (Romer and Jamieson, 2020), and intentions to become vaccinated (Earnshaw et al., 2020; Romer and Jamieson, 2020). In sum, there seems to exist a portion of the population that possesses a propensity to believe, or at least hold plausible, conspiracy theories that propagate throughout the information environment, and in response, adjust their behavior in a manner accordingly. In the following sections, we explore current work done to understand the personality factors that have been identified as diagnostic indicators of a person’s propensity to believe untrue or potentially misleading information and propose an expansion of the role of personality by including the socially aversive so-called ‘dark triad’ traits that have been examined in the literature.

The role of personality

Intuitively, whether a person is influenced by misinformation in the information environment depends on their ability to identify it as misinformation in the first place. But to what extent might personality make one more or less able to do so? While personality is traditionally assessed using the Big Five model of personality (John et al., 1991), for this article, we used a framework of personality that includes a sixth trait, Honesty-Humility (Ashton et al., 2014; Ashton and Lee, 2007), with the remaining five traits sharing much similarity with the Big Five. Together, they are (along with their behavioral and emotional tendencies in parentheses): Honesty-Humility (honest, sincere, fair, modest), Emotionality (vulnerable, sensitive, anxious), eXtraversion (confident, enjoy social gatherings, positive feelings), Agreeableness (peaceful, gentle, patient, agreeable), Conscientiousness (diligent, organized, planning), and Openness (curiosity, imaginativeness, depth). In what follows we provide a brief overview of work done to explore how personality is related to the ways in which a person interacts with the information environment.

Calvillo et al. (2021) reported that individuals higher on Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness, and lower on Extraversion, showed better accuracy in discriminating between real and fake news headlines (Calvillo et al., 2021). Hence, it is plausible that individuals high on these traits tend to authenticate whether headlines are true before sharing them online. Several published studies support this notion. Sampat and Raj (2022) found that individuals higher in Agreeableness and Conscientiousness had an increased tendency to vet news stories before sharing them. By contrast, they found that those higher in Extraversion and Neuroticism demonstrated an elevated tendency to share news stories online prematurely rather than vetting them. In addition, higher Agreeableness has been associated with a lower tendency to interact with suspicious Facebook posts (Buchanan and Benson, 2019). In sum, personality traits seem to shape how content in the information environment is regarded and treated.

While most of the existing research on personality and misinformation rely on the traditional Big Five model of personality (John et al., 1991), this model does not include the trait of Honesty-Humility—a trait that has been implicated in online behavior. For example, Honesty-Humility has been found to predict a person’s tendency and willingness to behave in a careless manner in the information environment as indicated by its strong association with the frequency of risky online behaviors, and feelings of disinhibition when operating online (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020). Although there is a dearth of research studying Honesty-Humility and fake news belief, the related construct of Intellectual Humility (the tendency to be humble about, and acknowledge the limitations of, one’s own knowledge and understanding; Krumei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2016) provides theoretical support for the role of Honesty-Humility. Intellectual Humility is associated with less susceptibility to fake news and conspiratorial beliefs (Bowes and Tasimi, 2022) and more fact-checking behavior when encountering misinformation (Koetke et al., 2022; Koetke et al., 2023). In sum, Honesty-Humility seems to represent a highly predictive personality trait of the extent to which a person is susceptible to being influenced in the information environment. The first goal of this article, therefore, is to augment the contribution provided by Calvillo et al. (2021) that measured personality using the traditional five-factor model by including an examination of how Honesty-Humility contributes to the relationship using the HEXACO personality inventory (Ashton et al., 2014; Ashton and Lee, 2007).

An understanding of how personality traits influence susceptibility to online misinformation would be enhanced by an exploration of how the socially aversive dark triad traits of personality might also be related. Hodson et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis from which they concluded that the dark triad traits, which consist of psychopathy (i.e., impulsivity, lack of empathy), narcissism (i.e., a grandiose sense of self), and Machiavellianism (i.e., manipulative, amoral, and cunning) are not distinct from Honesty-Humility, but rather correspond to tendencies at the low end of the Honesty-Humility spectrum. Irrespective of whether high scores on the dark traits correspond to low Honesty-Humility, past research has identified an association between conspiratorial beliefs and the dark personality traits, however the pattern of results are inconsistent. For example, in a set of three studies, Cichocka et al. (2016) found that narcissism was related to conspiracy theory belief. Similarly, Lantian et al. (2017) found that a greater need for uniqueness, which is a feature of narcissism (Emmons, 1984), leads to greater belief in conspiracy theories. By contrast, March and Springer (2019) found that Machiavellianism and psychopathy, and not narcissism, predict conspiratorial beliefs. Relatedly, willingness to conspire has been reported to mediate the relationship between Machiavellianism and conspiratorial belief, such that that individuals who conspire against others tend to believe that they are likely to be conspired against (Douglas and Sutton, 2011). In more recent work, still others have found that all three dark triad traits were related to COVID-19 specific conspiracy theory belief (Giancola et al., 2023; Hughes and Machan, 2021). The differences across studies may be partially explained by the different scales used to measure the dark triad traits among studies. Overall, the dark triad traits may lead to conspiratorial belief due to one’s need to feel special and know things others do not (an element of narcissism), a high level of mistrust in others (present in psychopathy), or the high willingness to conspire (exhibited in high Machiavellianism).

What is less clear from our examination of the literature is the role that the dark personality traits play in the detection of misinformation in the information environment. Recent research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that, similar to individuals who believed misinformation about COVID-19, individuals higher in the dark triad traits were less likely to partake in health promoting behaviors (Ścigała et al., 2021; Zajenkowski et al., 2020), like handwashing (Nowak et al., 2020; Triberti et al., 2021), mask-wearing (Chávez-Ventura et al., 2022), and willingness to get vaccinated (Howard, 2022) than people lower on these traits. However, this pattern may not necessarily be due to misinformation belief, it could indicate a general tendency for people high on the dark traits to behave in a selfish, self-centered, self-important manner. The most convincing study to suggest that the dark triad traits could be associated with misinformation detection was by Triberti et al. (2021) who reported that individuals higher on all three dark triad traits endorsed spreading alarming news before verifying it was true. However, it is unclear whether the pattern exhibited by Triberti et al.’s participants indicated an inability to discern misinformation, or the lack of motivation to do so. To better understand the role that personality plays in one’s identification of misinformation, we have included a measure of the Dark Triad traits alongside the HEXACO traits to determine how the collection of personality traits predicts one’s discernment of true from fake news headlines. Based on the results reported by Triberti et al., and the evidence suggesting that the dark triad traits represent component features associated with low Honesty-Humility (Hodson et al., 2018), we predict that greater narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism should be associated with a decreased ability to discern real from fake news stories.

Careless online behavior

Besides personality, the current study examines how one’s propensity to engage in unsafe or risky online behaviors and interactions might make them less sensitive to misinformation propagated within the information environment. Individuals who feel increased disinhibition online show an increased willingness to participate in risky online behaviors, such as disclosing personal information to others, and a higher frequency of falling victim to social engineering attacks (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020). In addition, individuals who report a willingness to form relationships online have an increased tendency to disclose personal information, leaving them vulnerable to deception, whereas people who are more suspicious of others’ intentions online tend to be more conscientious, and thus may be better protected against deception from others online (D’Agata et al., 2021).

The way in which users interact with information and others online seems therefore to be shaped by the level of trust (or level of suspicion) they feel in exploring or consuming information from unknown sources and forming relationships with individuals who have only ever presented themselves online. It has been established that personality factors are associated with one’s tendency and willingness to engage in risky online behaviors (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020) and one’s willingness to form relationships with others completely online (D’Agata et al., 2021). Common to both studies are the idea that some people have a high tolerance for risk when operating online—a risk that seems to have its basis in a tendency to trust the information presented to them. We postulate therefore, that the factors that put people at risk for social engineering and romance scams might also be at play in one’s tendency to believe unverified content presented in the information environment. Hence, in the current study, we tested the hypothesis that people who have a willingness, tendency, or history of reckless online behavior will exhibit a diminished ability to discern real from fake news headlines.

Demographic characteristics

In the misinformation and fake news literature, the effects of a variety of demographic variables have been studied, including gender, religiosity, and age. In the following section, we outline the current evidence for demographic differences in susceptibility to misinformation and fake news.

Gender

The effect of gender on belief in misinformation is inconsistent in the literature. Some studies have found that women had a higher prevalence of sharing misinformation on social media than men (e.g., Chen et al., 2015), while others have found no significant gender differences in detecting or sharing misinformation (Almenar et al., 2021; Mansoori et al., 2023). These differences are likely due in part to the heterogeneity between studies, particularly in the types of misinformation used and cultural differences in the sample. For example, Mansoori et al. (2023) noted that despite finding no gender effects, they had predicted an impact of gender because the sample used men and women from the United Arab Emirates, a traditionally patriarchal culture where genders differ in access to news and technology. Most of the research on gender differences in conspiracy theories have also found null results (e.g., Farhart et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2016), though some research using COVID-19 conspiracy theories specifically found women reported less belief than men (Cassese et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021). It is likely the case that gender does not have a consistent effect on all fake news and misinformation belief and may play a more significant role when certain types of misinformation are used, such as when gendered narratives are leveraged to influence conspiracy theory belief (Bracewell, 2021). A discussion of gendered narratives is beyond the scope of this article, but a review of the literature makes clear that gender is an important demographic variable to measure and test in the current study.

Religious beliefs

Religiosity has also been implicated as a correlate to misinformation belief. Greater religious beliefs have been associated with belief in fake news (Bronstein et al., 2019), and political and medical conspiracy theories (Galliford and Furnham, 2017). This susceptibility to misinformation may be due to differences in thinking styles. Religious skeptics showed more use of an analytical thinking style (Pennycook et al., 2012; Pennycook et al., 2014; Shenhav et al., 2012), less errors on logical reasoning problems (Pennycook et al., 2013), and better performance on tests of critical thinking skills (Pennycook et al., 2016). Based on these associations in the literature, we expect to find that participants who self-report as high on a scale of religiosity will be less skilled at discerning fake from real news than those who report low religiosity.

Age

Age is a point of focus in the misinformation literature; Many media literacy campaigns target young people (e.g., Schulten, 2022) and there is evidence that exposure to fake news and misinformation can have deleterious effects on youth (Dhiman, 2023). This specific focus on youth could be due to the significant amount of time younger generations spend on the internet and social media (Pérez-Escoda et al., 2021)—a place where fake news and misinformation proliferate. Compounding this exposure risk is that younger people may not have developed the critical thinking skills (Kuhn, 1999) required to combat misinformation. Indeed, there is evidence that younger people tend to believe general conspiracy theories (Galliford and Furnham, 2017) and fake news (Halpern et al., 2019), more than older people. We expect to replicate the reported patterns in the current study.

The current research

In this study, we sought to examine the role that personality, the propensity for careless or risky online behavior, gender, religiosity, and age play in predicting one’s accuracy in discerning real from fake content presented in the online information environment. It is our view that with a better understanding of the antecedents of misinformation belief, educational materials to enhance media literacy can be enhanced to reduce the public’s susceptibility to it. However, with respect to personality, we acknowledge that traits are considered relatively fixed and resistant to change. Accordingly, our goals for the work presented here exclude any suggestion that resilience to misinformation requires adjustments to one’s personality. Instead, we hope that training materials for media literacy can incorporate our findings about personality to include components that explain how personality relates to susceptibility to misinformation belief, and perhaps even include personality measures to promote self-awareness about how one’s own traits could put them at risk online.

The literature suggests that personality influences one’s susceptibility to misinformation (e.g., Calvillo et al., 2021)—a finding we predict will be replicated in the current study. The current research augments the work testing the relationships to the Big Five personality traits by Calvillo et al. (2021) to include a consideration of how Honesty-Humility (and the three dark triad personality traits that may be associated with those low on the Honesty-Humility dimension) relates to a person’s accuracy in discerning real from fake information. Based on work demonstrating a relationship between intellectual humility and belief in fake news and conspiracy theories (Bowes and Tasimi, 2022), an association between low Honesty-Humility and a heightened tendency to make oneself vulnerable while operating online (e.g., (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020), and the evidence suggesting that the dark triad traits represent component features associated with low Honesty-Humility (Hodson et al., 2018), we predicted that (H1) lower Honesty-Humility and (H2) higher scores on the dark triad traits of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism would be associated with decreased accuracy in discerning real from fake information.

We also predicted that those who show a willingness and tendency to interact with information and strangers online in manners that put them at risk for falling victim to scams or other online criminal acts (e.g., D’Agata et al., 2021) will also demonstrate a lack judgment when faced with new information of ambiguous veracity. Hence, we hypothesized that individuals who tend to be (H3) disinhibited and reckless online (i.e., higher scores on the careless online behavior measures) will perform more poorly in a task that asks them to discern real from fake information than those who show good judgement online.

Finally, we collected demographic data to identify factors that relate to discernment of truthful from false information. We expected to demonstrate the same patterns with respect to age and religion already documented in the literature, such that (H4) lower age and (H5) less religiosity will be related to better accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake news. In terms of gender, the results in the literature are inconsistent, likely due in part to the heterogeneity of study methods, especially the types of misinformation used across studies. Since we do not employ specific gendered narratives and use a wide range of misinformation in our fake news content, (H6) we did not expect to find gender differences in accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake news.

Method

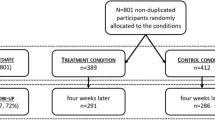

Participants

This research was granted approval by our organization’s Human Research Ethics Committee. We conducted an a priori power analysis based on a small effect size and determined a goal sample size of 500 participants. We used Qualtrics Panels to recruit participants, which is a web-based survey platform that allows researchers to build and monitor surveys, while Qualtrics Panels distributes the survey links and collects data on the researchers’ behalf.Footnote 2 To be eligible for the study, participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 80, live in the US or Canada, and be fluent in English. In addition, partial responses were not recorded, and those who failed any of the validity checks for random responses were removed from the sample. Further, respondents with completion times that were extreme outliers or those who took 50% less than the median time to complete the survey were removed.

The sample (N = 510) comprised of Canadian and American adults (see Table 1). The sample included 315 females and 188 males (four participants identified outside of the gender binary), ranging in age from 18–80 (M = 39.8, SD = 15.8). In our sample, 83.3% had some post-secondary education, and 60.6% of the sample was currently employed.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

Participants completed questions on demographic characteristics, including gender, age, highest level of education, and current employment status. In addition, they completed a religious belief scale to assess religiosity and spirituality (Pennycook et al., 2016). The questionnaire contains items such as, “I believe in heaven” and “I believe in demons,” and uses a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Online behavior measures

Risky Online Behaviors

We used the Risky Online Behaviors scale (ROB; D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020) which includes a range of online behaviors for which participants are asked to indicate how often they have engaged in each. Items were rated using a 5-point frequency scale: 0 (never), 1 (1 time), 2 (2 times), 3 (3–5 times) and 4 (more than 5 times). The measure is not a psychometric tool but rather a count of the frequency with which a person has engaged in risky online behaviors. Behaviors range from the relatively benign (“I’ve posted personal information in comments on social media that were public”) to ones that make the participant vulnerable (e.g., “I’ve disclosed a password to one of my own accounts via email”). The measure indicated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Online Disinhibition

We used the Online Disinhibition scale (OD; D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020) to assess the extent to which individuals feel disinhibited online in the manner described by Suler (2004). The measure includes 20 items designed to measure comfort and feelings of anonymity while operating online. Example items include, “I don’t need to monitor my behavior online as much as I do offline” and “I have a different personality online than I do in the real world”. Items are rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measure indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Openness to Form Online Relationships

We used the Openness to Form Online Relationships scale (OFOR; D’Agata et al., 2021) to assess one’s willingness to develop friendships and romantic relationships with strangers online. The 6-items are rated on a 5-point rating scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and consists of two subscales: Engagement, a measure of a person’s level of comfort in engaging with strangers online (good internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and Suspicion, a measure of a person’s level of mistrust of others while operating online (acceptable internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.63).

Personality measures

HEXACO Personality Inventory

We used the 100-item HEXACO Personality Inventory —Revised (HEXACO–PI–R; Lee and Ashton, 2018), to assess the six-factor model of personality (Honesty-Humility, Emotionality, eXtraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness). Participants rated the items (e.g., “people sometimes tell me that I am too critical of others” and “I avoid making ‘small talk’ with people” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The subscales indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α’s = 0.74–0.85).

The Short Dark Triad

We used the 27-Item Short Dark Triad (SD3; Jones and Paulhus, 2014) to measure the three socially aversive dark triad personality traits (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Participants were asked to rate the items (e.g., “It’s not wise to tell your secrets”, and “I like to get acquainted with important people”) using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The subscales indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α’s = 0.75–0.83).

Discerning real from fake information: The Headline Task

Twelve real and twelve fake headlines were selected from Peter et al.’s (2021) headline task which used real news and fake news headlines published on the internet and was adapted from Pennycook and Rand (2019). Mainstream news sources, such as CBC News and The New York Times were used to select real news headlines. These sources fell anywhere from far-left to far-right on the political spectrum. The real news headlines included topics such as climate change, government spending, and teen drug use. Headlines categorized as fake were selected from articles labeled as ‘false’ by Snopes.com, a fact-checking resource that directly evaluates information in the news. Examples of news stories featured in the fake news headlines include inmates outliving life sentences, micro-chipping campaigns, and animal limit laws. The headlines were categorized into three bins based on data from Peter et al. (2021) where headlines were classified as high accuracy (i.e., most of their participants accurately identified that the headline was either real or fake), 50–50 accuracy (i.e., ~50% of their participants were accurate), and low accuracy (i.e., most of their participants did not accurately identify that the headline was either real or fake). We selected eight headlines from each bin (four real and four fake) to use in the current study.

Participants were shown each headline separately and were told that while some may be real or accurate, others may not be. For each headline, participants were asked to rate whether they think the headline is from a real or fake news story. Task performance was assessed using measures borrowed from signal detection theory (Stanislaw and Todorov, 1999). Specifically, sensitivity, or accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake headlines was assessed by calculating the statistic d’. Response bias (i.e., a tendency for one response to be favored over the other regardless of veracity) was assessed by calculating the statistic c.Footnote 3

Procedure

Following the completion of the demographic questionnaire, participants completed the Headline Task where real and fake headlines were presented in randomized order. Next, they completed the Online Disinhibition Scale, Risky Online Behavior Scale, Openness to Form Online Relationships Scale, The HEXACO-PI-R, and the SD3 in a randomized order.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all measures are reported in Table 2 and correlations among all measures are reported in Table 3.

Headline task accuracy

First, we examined the associations between performance on the Headline Task and the demographic variables, using two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with an alpha level of 0.05. Age was not significantly correlated with headline task accuracy (r = 0.03, p = 0.49). Religiosity was negatively correlated with headline task accuracy, such that people who were lower on religiosity were better at distinguishing between real and fake news headlines (r = −0.24, p < 0.001). A two-tailed paired samples t-test with an alpha level of 0.05 indicated no significant difference in headline task performance between men and women (t(501) = −0.77, p = 0.44).

As expected, the different personality and online behavior variables were associated with one’s discernment of real from fake news. We conducted two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.004 to control for the Type I error rate due to multiple comparisons (see Table 3 for correlations among all measures). The correlational analysis provided support for our a priori predictions that poorer performance on the Headline Task would be associated with lower feelings of suspicion towards others’ intentions online (r = 0.16), greater willingness to engage in relationships with strangers online (r = −0.19), and greater online disinhibition (r = −0.23), and greater risky online behaviors (r = −0.18; all p’s < 0.001). With respect to the personality measures, lower Honesty-Humility (r = 0.22), lower Openness (r = 0.16), and lower Conscientiousness (r = 0.20) were associated with poorer performance on the Headline task, as were greater Machiavellianism (r = −0.19), greater narcissism (r = −0.22), and greater psychopathy (r = −0.25; all p’s < 0.001).

Headline task response bias

To test whether personality and individual differences were associated with a particular response pattern, we correlated response bias (i.e., c) with the personality and online behavior measures (see Table 3). A positive c statistic indicated a tendency toward responding “true” to a headline regardless of its veracity, and a negative c statistic indicated a tendency toward responding ‘false’. The two-tailed Pearson’s correlation tests with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.004 indicated a significant bias toward rating the headlines as true among those who reported greater online disinhibition (r = 0.23), greater risky online behaviors (r = 0.28), and greater willingness to engage with strangers online (r = 0.19; all p’s < 0.001). The same bias was found among those reporting higher levels of Machiavellianism (r = 0.22), narcissism (r = 0.21), and psychopathy (r = 0.26; all p’s < 0.001). Finally, lower Honesty-Humility (r = −0.21, p < 0.001) was associated with a bias toward indicating a headline is true. We did not find that suspicion of others’ intentions online, and the remaining personality traits, were significantly correlated with response bias.

Discussion

Overall, our findings suggest that there are psychological and personality factors that affect the accurate assessment of the veracity of information encountered online. Individuals who self-reported as less diligent and organized (lower Conscientiousness), less curious and imaginative (lower Openness), and less sincere and honest (lower Honesty-Humility) demonstrated a diminished discernment between fake from real headlines. Consistent with the features of those who score low on Honesty-Humility, those high on the dark triad traits, and therefore those who self-report as more manipulative and cunning (higher Machiavellianism), more selfish and paranoid (higher Narcissism), and more impulsive and callous (higher Psychopathy) exhibited the same reduced accuracy, and a bias toward considering headlines as being ‘true’. Finally, those who were careless online (i.e., feeling more disinhibited online, more willing to engage with and share personal information with strangers online, or being less suspicious of strangers’ intentions online) were less accurate in discerning between fake and real news headlines, and similarly exhibited a bias towards considering the headlines to be true.

Our results confirm previously reported associations between personality and susceptibility to misinformation and provide some novel contributions. Although our personality results partially replicated Calvillo et al. (2021) with greater fake news detection accuracy being associated with higher Openness and Conscientiousness, unlike Calvillo et al., correlations for the role of Extraversion and Agreeableness did not reach significance; however, this could have resulted from the use of a different personality assessment tool or any differences between our task and theirs.

The novel contribution to the body of work is our finding that low levels of Honesty-Humility, and its associated high scores on dark triad traits, are related to a reduced accuracy in distinguishing real from false information, and an apparent bias toward interpreting information they encounter as true—a pattern suggesting that the lack of accuracy in identifying fake news from real news could be due to the tendency to consider all information as truthful. While results in the literature are mixed on the relationship between the dark triad traits and conspiratorial belief, with some studies finding only some of the triad traits having significant associations (e.g., Cichocka et al., 2016; March and Springer, 2019), our results align most closely with Hughes and Machan (2021) and Giancola et al. (2023) who found that greater levels of all three dark triad traits were associated with greater endorsement of conspiracy theories. Our results complement and build upon their findings by raising the possibility that the lower accuracy in distinguishing real from fake news headlines among those who score low on Honesty-Humility may be because the dark triad traits represent Honesty-Humility’s key features (n.b. Hodson et al., 2018). Based on our analysis of response bias, we propose further that individuals with greater dark triad traits could be especially susceptible to accepting conspiracy theories (Cichocka et al., 2016; Douglas and Sutton, 2011; Giancola et al., 2023; Hughes and Machan, 2021; Lantian et al., 2017; March and Springer, 2019) because of a general tendency or bias to believe information, thus making them more apt to consider far-fetched claims about government conspiracies to be believable or probable.

In addition to the personality factors we explored, our data showed that engaging in careless online behavior, including one’s willingness to form relationships with others online, was associated with a diminished accuracy in discerning real from fake content in the online environment, and with a bias toward considering information as true. In past research, greater feelings of disinhibition while operating in the online environment was associated with an increased frequency of risky online behaviors and an openness to forming online relationships, as well as less suspicion toward others’ intentions online (D’Agata and Kwantes, 2020; D’Agata et al., 2021). Our data replicate this pattern which, in addition to supporting their notions about the drivers of online misbehavior, helps to confirm the validity of their measures for OD and OFOR as predictors for performance on a task that measures detection of fake from real news headlines. A person’s increased willingness to put themselves at risk in the information environment through interactions with either information or strangers, or put another way, the increased trust they are willing to place in information or strangers in the information environment, raises the likelihood that they will be inaccurate when distinguishing between fake and real information, and that they will interpret information presented to them online at face value, rather than approaching it with skepticism.

Lastly, our findings are generally consistent with those of others who have explored the demographic factors that influence receptivity to misinformation. We found no evidence of gender differences in accuracy on our fake news task, which used headlines across a broad range of topics, and is in line with much of the literature on misinformation and gender (e.g., Almenar et al., 2021; Farhart et al., 2020; Mansoori et al., 2023; Miller et al., 2016). It is possible that gender differences emerge depending on the type of misinformation, such as the findings of greater belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories by men than women (Cassese et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021), or when gendered narratives are employed (Bracewell, 2021). Our results were also consistent with previous findings regarding age and religious beliefs. In line with Halpern et al. (2019) and Galliford and Furnham (2017) we found that younger participants were less able to identify fake information than older participants. We also found that greater religiosity was associated with lower accuracy when distinguishing between fake and real news, in line with other findings that have linked religious beliefs and the acceptance of misinformation as true (Bronstein et al., 2019; Galliford and Furnham, 2017). The replication of the age and religious effects is interesting. With respect to age, one could surmise that younger individuals’ lack of life experience may limit their willingness to question new information. For those who hold established institutions up as credible sources of information, individuals may be increasingly willing to consume new information as true without an accompanying inclination or drive to verify information on their own. In either case, the results point to a need for measures to promote critical thinking among consumers of information.

Implications

A common thread in our findings is the idea that aspects of trust seem to play a role in distinguishing truthful from false information. Individuals who tend to be less sincere and honest, more impulsive, manipulative, and self-involved–and therefore less trustworthy–are more likely to accept information as being true, perhaps due to an underlying belief that because they tend to be sneaky and deceitful, they are immune to being duped themselves. We also found that individuals who were more trusting of strangers online and thus engaged more frequently in relationships with them and shared more personal information online were also more likely to accept information as true. Together, the results point to ways in which training and education programs for media literacy could be designed as interventions for reducing susceptibility to misinformation and fake news. At a high level, our results point to the possibility that training for media literacy should highlight the importance of thinking critically about the information one encounters, as well as the value of approaching new information with the acknowledgement or understanding that any new information might be false, whether it is intentionally meant to deceive or not.

More importantly however, our results can inform efforts to incorporate the psychology of misinformation detection into educational materials designed to protect individuals operating online. As mentioned above, we acknowledge personality to be relatively fixed, thus efforts to change it is not the goal. Instead, we propose that media literacy materials which include personality measures and explanations about how personality traits relate to susceptibility to misinformation, as well as creating awareness of one’s own susceptibility to misinformation could be highly useful. For example, training that emphasizes the importance of diligence and the careful assessment of new information may resonate with those high on Conscientiousness, or high on Honesty-Humility—groups that are, based on our findings, at a lowered risk for belief in misinformation to begin with. But those who score low on Conscientiousness or Honesty-Humility could benefit from training materials that draw their attention to their own susceptibility and the personal costs of believing misinformation. The materials could also suggest new habits that could be developed to counter some of those tendencies. Training that incorporates this aspect of self-awareness about how one’s personality traits place them at risk for believing misinformation may be critical in encouraging people to resist initial tendencies to accept new information as true.

Education regarding the dangers of risky online behaviors could be leveraged as well. Media literacy programs that teach individuals to be suspicious of others’ intentions online and to evaluate information with a critical eye, and importantly, programs that include information about how trainees’ own individual tendencies could put them at risk when assessing information online could be of value. Equipped with some knowledge about how one’s own personality relates to how new information and interactions experienced online will be processed, individuals may be better able to calibrate themselves with respect to any biases they may possess with respect to their propensity to trust new information or online actors. A strategy used in some media literacy training is to encourage fact-checking new information using sources that are considered reliable. This not only encourages users of the information environment to approach new information with some degree of skepticism, but it is also consistent with best practices in Western intelligence communities who are trained to seek validation or falsification of information provided during intelligence collection. Intelligence analysts verify new information because the cost of being wrong is great. In a similar fashion, the consequences of having one’s behavior and attitudes shaped by unverified information posted online can also be significant when it is misleading or false.

In addition to our recommendations regarding the content of media literacy training, the finding that younger and more religious individuals showed a diminished accuracy in distinguishing real from fake news point to schools and religious institutions as potential routes of delivery for these training programs. The implementation of media literacy training programs in schools should continue to grow as part of the educational curriculum. In addition, community religious leaders could, as trusted messengers, play a role in countering misinformation, as well as in informing community members about the importance of facing new information with a critical perspective. Regardless of the intended audience for such programs, further work to develop, customize, and personalize media literacy programs for the digital age may be essential to combat the uptake of misinformation.

Limitations and future directions

We note that the effect sizes for our analyses were small. Small effect sizes are common in psychological research especially when studying a complex psychological phenomenon (Funder and Ozer, 2019; Götz et al., 2022) such as belief in, and detection of, fake news. Although our results indicated that personality traits and reckless online behavior online may play a role in predicting detection of misinformation, the variables we tested are not exhaustive. In our view, the tendency and ability to think critically, and the willingness to fact-check and scrutinize online information are also factors to explore for inclusion in media literacy programs designed as interventions to counter the threat of fake news belief.

As with many studies that use self-report measures, the data used in our study may be influenced by socially desirable responding, especially for our measure of the dark triad which asks about anti-social behaviors that many may be hesitant to admit committing, as well as the online behavior measures, which could be embarrassing to admit to engaging in. Past research also indicates a potential for inaccurate self-reporting of online behavioral tendencies (Parry et al., 2021). Future research could use alternative measures, such as peer reports of careless online behavior and fake news belief to verify the self-report measures. Future research could also survey individuals who have fallen for fake news in the past, or communities who deeply believe misinformation or conspiracy theories, to investigate their personality traits and behavioral tendencies online.

As a correlational study with somewhat limited scope with respect to the number of variables being studied, we cannot say for certain that there are no other, yet unexplored, intervening variables that also play a role in fake news detection. As such, the extent to which we can claim that careless online behaviors and personality traits are causing performance on the headline task has limits. A fuller treatment of the variables that underpin one’s difficulty in discerning real from fake news could be explored in future studies that implement longitudinal designs or experimental research. While expensive and time consuming to conduct, such studies may go some way to help us identify the causal nature of the effects. Lastly, future work to replicate the effects with pre-registration would be beneficial to enhance confidence in the reproducibility of our findings.

Conclusion

In sum, personality traits and careless online behavior appear to influence one’s discernment of real from fake information online. The findings were not altogether surprising given the results reported by D’Agata and Kwantes (2020) and D’Agata et al. (2021). However, they point to potentially useful directions for increasing the efficacy of media training by including a component that encourages self-awareness about one’s own potential to be influenced by information and strangers encountered online. Our results pertaining to the dark triad traits and the manner in which they explain how Honesty-Humility predicts enhanced detection of, and potentially one’s subsequent susceptibility to, misinformation is potentially the most theoretically interesting finding of this article because it exposed a common theme across our variables related to trust—among those who seem predisposed to trust misinformation and strangers online, are those who themselves should not be fully trusted. Indeed, the concept of trust could form the core of media literacy training models that concentrate on raising people’s self-awareness about their own susceptibility to online misinformation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository, https://osf.io/mscy6/?view_only=3cb2b1f8666045ab87ea5982cd91047c.

Notes

There are different types of false and inaccurate information that proliferates the internet. Specifically, disinformation refers to false or misleading information that is malicious and spread intentionally, whereas misinformation is false or misleading information but is spread without malice (Bennett and Livingston, 2018; Lewandowsky et al., 2013). Fake news is a more colloquial term, that refers to news articles or headlines that have been debunked or proven to be false. With the rise in internet use and political tensions, disinformation, fake news, and conspiracy theories are spreading at a rapid pace. Given the challenges associated with ascertaining if something was maliciously intended, we conceptualize fake news and conspiracy theories to be ‘misinformation’.

To ensure that those who participated in our earlier series of surveys did not participate in this study, all potential respondents were cross-checked by Qualtrics Panels.

Sensitivity is calculated as the z transform of the hit rate minus the z transform of the false alarm rate, and response bias is calculated as the z transform of the hit rate plus the z transform of the false alarm rate divided by −2. (Stanislaw and Todorov, 1999).

References

Allington D, Duffy B, Wessely S, Dhavan N, & Rubin J (2020) Health-protective behavior, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psycholog Med 51(10):1–7

Almenar E, Aran-Ramspott S, Suau J, Masip P (2021) Gender differences in tackling fake news: Different degrees of concern, but same problems. Media Commun 9(1):229–238

Ashton MC, Lee K (2007) Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 11(2):150–166

Ashton MC, Lee K, De Vries RE (2014) The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: a review of research and theory. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 18(2):139–152

Bennett WL, Livingston S (2018) The disinformation order: disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. Eur J Commun 33(2):122–139

Bierwiaczonek K, Kunst JR, Pich O (2020) Belief in COVID‐19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Appl Psychol Health Well‐Being 12(4):1270–1285

Bowes SM, Tasimi A (2022) Clarifying the relations between intellectual humility and pseudoscience beliefs, conspiratorial ideation, and susceptibility to fake news. J Res Personal 98:104220

Bracewell L (2021) Gender, populism, and the QAnon conspiracy movement. Front Sociol 5:1–4

Bronstein MV, Pennycook G, Bear A, Rand DG, Cannon TD (2019) Belief in fake news is associated with delusionality, dogmatism, religious fundamentalism, and reduced analytic thinking. J Appl Res Mem Cogn 8(1):108–117

Buchanan T, Benson V (2019) Spreading disinformation on Facebook: do trust in message source, risk propensity, or personality affect the organic reach of “fake news”? Soc Media+ Soc 5(4):2056305119888654

Calvillo DP, Garcia RJ, Bertrand K, Mayers TA (2021) Personality factors and self-reported political news consumption predict susceptibility to political fake news. Personal Individ Differ 174:110666

Cassese E, Farhart C, Miller J (2020) Gender differences in COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Politics Gend 16(4):1009–1018. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000409

Cichocka A, Marchlewska M, Golec de Zavala A (2016) Does self-love or self-hate predict conspiracy beliefs? Narcissism, self-esteem, and the endorsement of conspiracy theories. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 7(2):157–166

Chávez-Ventura G, Santa-Cruz-Espinoza H, Domínguez-Vergara J, Negreiros-Mora N (2022) Moral disengagement, dark triad and face mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Investig Health, Psychol Educ 12(9):1300–1310

Chen X, Sin SCJ, Theng YL, Lee CS (2015) Why students share misinformation on social media: Motivation,gender, and study-level differences. J Acad Libr 41(5):583–592

D’Agata MT, Kwantes PJ (2020) Personality factors predicting disinhibited and risky online behaviors. J Individ Differ 41(4):199–206

D’Agata MT, Kwantes PJ, Holden RR (2021) Psychological factors related to self-disclosure and relationship formation in the online environment. Personal Relatsh 28(22):230–250

Dhiman B (2023) The rise and impact of misinformation and fake news on digital youth: a critical review. J Socialomics, 12(3)

Douglas KM (2021) COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Process Intergroup Relat 24(2):270–275

Douglas KM, Sutton RM (2011) Does it take one to know one? Endorsement of conspiracy theories is influenced by personal willingness to conspire. Br J Soc Psychol 50(3):544–552

Earnshaw VA, Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Brousseau NM, Hill EC, Fox AB (2020) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl Behav Med 10(4):850–856

Emmons RA (1984) Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. J Personal Assess 48(3):291–300

Farhart CE, Miller JM, Saunders KL (2020) Conspiracy stress or relief? Learned helplessness and conspiratorial thinking. In The politics of truth, eds. Elizabeth Suhay and David Barker, 1–38. Oxford University Press

Funder DC, Ozer DJ (2019) Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 2(2):156–168

Galliford N, Furnham A (2017) Individual difference factors and beliefs in medical and political conspiracy theories. Scand J Psychol 58(5):422–428

Giancola M, Palmiero M, D’Amico S (2023) Dark triad and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: the role of conspiracy beliefs and risk perception. Curr Psychol, 1–13

Götz FM, Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ (2022) Small effects: the indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci 17(1):205–215

Grebe E, Nattrass N (2012) AIDS conspiracy beliefs and unsafe sex in Cape Town. AIDS Behav 16(3):761–773

Halpern D, Valenzuela S, Katz J, Miranda JP (2019) From belief in conspiracy theories to trust in others: Which factors influence exposure, believing and sharing fake news. In: Meiselwitz G (eds) Social computing and social media. design, human behavior and analytics. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11578. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21902-4_16

Hodson G, Book A, Visser BA, Volk AA, Ashton MC, Lee K (2018) Is the dark triad common factor distinct from low honesty-humility? J Res Personal 73:123–129

Howard MC (2022) The good, the bad, and the neutral: vaccine hesitancy mediates the relations of Psychological Capital, the Dark Triad, and the Big Five with vaccination willingness and behaviors. Personal Individ Differ 190:111523

Hughes S, Machan L (2021) It’s a conspiracy: Covid-19 conspiracies link to psychopathy, machiavellianism, and collective narcissism. Personal Individ Differ 171:110559

John, OP, Donahue, EM, Kentle, RL (1991). Big five inventory. J Personal Soc Psychol

Jolley D, Douglas KM (2014) The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 9(2):1–9

Jones DN, Paulhus DL (2014) Introducing the short dark triad (SD3) a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment 21(1):28–41

Kim S, Kim S (2021) Searching for general model of conspiracy theories and its implication for public health policy: analysis of the impacts of political, psychological, structural factors on conspiracy beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(1):266

Koetke J, Schumann K, Porter T (2022) Intellectual humility predicts scrutiny of COVID-19 misinformation. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 13(1):277–284

Koetke J, Schumann K, Porter T, Smilo-Morgan I (2023) Fallibility salience increases intellectual humility: implications for people’s willingness to investigate political misinformation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 49(5):806–820

Krumei-Mancuso EJ, Rouse SV (2016) The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. J Personal Assess 98(2):209–221

Kuhn D (1999) The developmental model of critical thinking. Educ Res 28(2):16–25

Lantian A, Muller D, Nurra C, Douglas KM (2017) “I know things they don’t know!”: The role of need for uniqueness in belief in conspiracy theories. Soc Psychol 48(3):160

Lee K, Ashton MC (2018) Psychometric properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 25:543–556

Lewandowsky S, Stritzke WGK, Freund AM, Oberauer K, Krueger JI (2013) Misinformation, disinformation, and violent conflict: from Iraq and the “war on terror” to future threats to peace. Am Psychol Assoc 68:487–501

Mansoori A, Tahat K, Tahat D, Habes M, Salloum SA, Mesbah H, Elareshi M (2023) Gender as a moderating variable in online misinformation acceptance during COVID-19. Heliyon, 9(9)

March E, Springer J (2019) Belief in conspiracy theories: the predictive role of schizotypy, machiavellianism, and primary psychopathy. PLoS ONE 14(12):e0225964. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225964

Miller JM (2020) Psychological, political, and situational factors combine to boost COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs. Can J Political Sci/Rev Can Sci Politique 53(2):327–334

Miller JM, Saunders KL, Farhart CE (2016) Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: the moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. Am J Political Sci 60(4):824–844

Nowak B, Brzóska P, Piotrowski J, Sedikides C, Żemojtel-Piotrowska M, Jonason PK (2020) Adaptive and maladaptive behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of Dark Triad traits, collective narcissism, and health beliefs. Personal Individ Differ 167:110232

Parry DA, Davidson BI, Sewall CJR, Fisher JT, Mieczkowski H, Quintana DS (2021) A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nat Hum Behav 5(11):1535–1547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01117-5

Pennycook G, Cheyne JA, Barr N, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA (2014) Cognitive style and religiosity: the role of conflict detection. Mem Cogn 42(1):1–10

Pennycook G, Cheyne JA, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA (2013) Belief bias during reasoning among religious believers and skeptics. Psychonom Bull Rev 20(4):806–811

Pennycook G, Cheyne JA, Seli P, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA (2012) Analytic cognitive style predicts religious and paranormal belief. Cognition 123(3):335–346

Pennycook G, Rand DG (2019) Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 188:39–50

Pennycook G, Ross RM, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA (2016) Atheists and agnostics are more reflective than religiousbelievers: Four empirical studies and a meta-analysis. PLoS One 11(4):e0153039

Peter E, D’Agata M, Kwantes P, & Vallikanthan J (2021) Individual differences in susceptibility to disinformation: an example using the COVID-19 pandemic. Defence Research and Development Canada

Pérez-Escoda A, Pedrero-Esteban LM, Rubio-Romero J, Jiménez-Narros C (2021) Fake news reaching young people on social networks: Distrust challenging media literacy. Publications 9(2):24

Pummerer L, Böhm R, Lilleholt L, Winter K, Zettler I, Sassenberg K (2022) Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 13(1):49–59

Romer D, Jamieson KH (2020) Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the US. Soc Sci Med, 263, 113356

Sampat B, Raj S (2022) Fake or real news? Understanding the gratifications and personality traits of individuals sharing fake news on social media platforms. Aslib J Inf Manag 74(5):840–876

Schulten K (2022) Teenagers and misinformation: some starting points for teaching media literacy. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/20/learning/lesson-plans/teenagers-and-misinformation-some-starting-points-for-teaching-media-literacy.html

Ścigała KA, Schild C, Moshagen M, Lilleholt L, Zettler I, Stückler A, Pfattheicher S (2021) Aversive personality and COVID-19: a first review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychol 26(4):348

Shenhav A, Rand DG, Greene JD (2012) Divine intuition: cognitive style influences belief in God. J Exp Psychol Gen 141(3):423–428

Stanislaw H, Todorov N (1999) Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 31(1):137–149

Suler J (2004) The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav 7(3):321–326

Thorburn S, Bogart LM (2005) Conspiracy beliefs about birth control: Barriers to pregnancy prevention among African Americans of reproductive age. Health Educ Behav 32(4):474–487

Triberti S, Durosini I, Pravettoni G (2021) Social distancing is the right thing to do: Dark Triad behavioral correlates in the COVID-19 quarantine. Personal Individ Differ 170:110453

van Prooijen JW, Acker M (2015) The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: conceptual and applied extensions. Appl Cogn Psychol 29(5):753–761

Zajenkowski M, Jonason PK, Leniarska M, Kozakiewicz Z (2020) Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19? Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Personal Individ Differ 166:110199

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Erika Peter: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Review and editing, Writing—Approval of final version Peter Kwantes: Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Review and editing, Writing—Approval of final version Madeleine D’Agata: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and editing, Writing—Approval of final version Janani Vallikanthan: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and editing, Writing—Approval of final version. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript. All authors contributed to research conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This research was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Defence Research and Development Canada—Toronto Research Centre (No. 2020-009).

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peter, E.L., Kwantes, P.J., D’Agata, M.T. et al. The role of personality traits and online behavior in belief in fake news. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1126 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03573-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03573-6

- Springer Nature Limited