Abstract

Bullying between peers is a well-known fact and during the last 20 years there has been considerable research on this topic. A topic that has received much less attention is bullying by teachers towards students. This article aims to review the research literature that exists on this important topic. The review covers articles about teacher bullying in elementary, primary, lower, and upper secondary schools, in a retrospective, prospective, or current perspective. The results show that teacher bullying occurs within school contexts all over the world in various ways and to various extents. Although the prevalence rates of bullying behaviors from school staff towards students vary greatly, from 0.6 to almost 90%, this review clearly shows there is a need to pay more attention to this challenge. Several studies show that being exposed to teacher bullying can adversely affect a child’s physical and mental health, participation in education and working life, and sense of well-being in adulthood. There is a need to address this topic in practical work, in teacher education, and in anti-bullying programs. Teacher bullying is also an important topic for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

According to the Convention of the Rights of the Child (1989), adults have a duty to do what is in the best interest of children. Additionally, as part of the Sustainable Development Goals of 2015, world leaders made a commitment to end all forms of violence against children by 2030. All countries are striving for improved practice at all levels of society, especially within the education system. In Norway, for example, the Norwegian Education Act (1998) requires all school staff to intervene in violations, and there is an even stronger obligation to act if someone working at the school suspects or determines that another person working at the school is violating a student by means of bullying, violence, discrimination, or harassment. The need to legislate what school staff should do if a colleague is violating students reveals that this issue represents a problem in schools. In 2019, the Norwegian Annual Pupil Survey showed that 1.6% of Norwegian students in primary, lower, and upper secondary schools experienced teacher bullying two or three times a month or more. Although the number is relatively low, it is a serious problem for those involved and thus emphasizes the need for more knowledge on the topic.

Established concepts of violation from adults towards children in the research literature are child abuse and neglect (Crosson-Tower, 2009; McCoy & Keen, 2009) and child maltreatment (Miller-Perrin & Perrin, 1999; Myers, 2010). According to the World Health Organization (2020), child maltreatment includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial, or other exploitation that results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development, or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power. Child maltreatment is therefore a very broad concept that covers a range of negative actions which children and youth may be exposed to that could be extremely devastating for their health, development, and learning. Child maltreatment in schools, however, has been explored to a lesser degree. There is a gap in the research literature regarding situations in which the teacher is the perpetrator with a focus on repeated harm to the same child. This phenomenon is conceptualized by a number of researchers as teacher bullying (e.g., Datta et al., 2017; Monsvold et al., 2011; Twemlow et al., 2006; Whitted & Dupper, 2008). This term is also used in the Norwegian Education Act (1998) and in the Norwegian annual pupil survey (Wendelborg, 2020).

Bullying is a well-established concept that has been defined across countries, contexts, and cultures worldwide as a long-standing negative behavior that is conducted by a group or an individual and is directed against a person who is not able to defend him- or herself (Olweus, 1983; Roland, 1999). A key question is whether this definition is used or is suitable for describing situations in which students are exposed to negative actions by teachers. The established definition of bullying has three characteristics: aggressive behavior (1), which is repeated (2) in an asymmetric power relationship (3). One of the criteria in the definition of bullying is already present in the relationship between teachers and students because power is unequally distributed. If a teacher exposes some students to aggressive behavior over time, the situation is quite similar to what we traditionally define as bullying and may thus be said to constitute a specific form of child maltreatment. A large body of research shows that peer bullying is a persistent problem within education systems and that bullying is damaging for students’ health and well-being in both the short run (Havik et al., 2015; Rueger & Jenkins, 2014; Sjursø et al., 2015) and the long run (Copeland et al., 2013; Fekkes et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006). If bullying is performed by a person who is supposed to be a caregiver and a role model, it can be assumed that the consequences may be even more devastating for the exposed child. Teacher-student relationships exert a major influence not only on students’ academic performance but also on social, emotional, and behavioral problems, especially in primary school (Pianta, 1999).

To date, research on school bullying has mainly focused on bullying between peers. As suggested by the example of Norwegian legislation, there is also a need to increase awareness of bullying by adults. It is therefore necessary to draw more attention to and expand the research field on bullying by including behavior from adults towards children and adolescents in the school context. According to Hyman (1990), teachers’ negative behavior may occur occasionally and rarely, or the behavior may become a repeated pattern of bullying directed at one particular student. Olweus was a pioneer in research on school bullying between students and was likely the first to reveal through a pilot study that schoolteachers overtly bullied one or more students on a regular basis (Olweus, 1996). Roland (1996) conducted a survey in which students reported experiences of bullying from teachers. Other than a few sporadic research initiatives, however, teacher bullying is very rarely mentioned in school safety or bullying literature. It is important to include this topic in the educational discourse because it may relate directly to the overall climate and bullying in the school (Benbenishty et al., 2018).

Thus, the aim of this article is to identify and review the existing research literature about different types of negative teacher behavior that we perceive as teacher bullying. Within this aim, our purpose is more specifically to gain knowledge about the prevalence of such bullying and to identify types of bullying behaviors and possible individual and contextual risk factors. We also aim to identify whether research can reveal the consequences of being bullied by teachers at school and findings regarding how to prevent and stop negative teacher-student interactions.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

In this review, studies on teacher bullying refer to studies that investigated bullying-related behavior towards students that took place in the school context. The perpetrator was a teacher or any other school staff, like educational assistant, teacher’s aide, occupational therapist, and school nurse. Moreover, the selected studies involved respondents who reported bullying from adults towards students in elementary, primary, lower, and upper secondary schools from a retrospective, prospective, or current perspective. To identify existing research on teacher bullying, we included terms that describe actions that are closely related to bullying behavior. The following terms were used as keywords: abusing, harassing, cyberbullying, teasing, maltreatment, violence, power, mistreatment, humiliation, victimization, and aggression. The review included only peer-reviewed papers in the Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, or English languages. No time restrictions were set.

Search Strategy

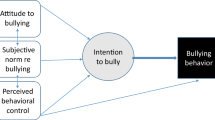

Our search strategy was inspired by methodologies for conducting scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, 2007; Levac, Colcuhoun & O’Brien, 2010; Peters et al., 2015). Scoping reviews are useful to probe and clarify the existing body of literature within a topic that lacks research attention. The search was conducted in August 2019. First, we conducted an initial and preliminary search in two databases (ERIC and SCOPUS). From this search, two of three researchers selected relevant publications by inspecting titles and abstracts and identified possible new keywords and index terms used in the descriptions. Furthermore, we conducted a comprehensive search in eight databases, including Academic Search Premier, SocIndex, Web of Science, PsychInfo, NorArt, and Oria in addition to ERIC and SCOPUS. Again, we selected publications by reading titles and abstracts, and we read the full text of those that met our inclusion criteria. Three researchers were involved in this process. The next step was to investigate the reference lists from these publications (N = 20). Finally, we examined conference programs that were available on the Internet or could be sent by e-mail. These were ECDP 2019, ISSBD 2018, EARA 2018 and 2016, and SRCD 2019 and 2017. Figure 1 illustrates our search strategy and the total number of studies included (N = 38).

Results

The 38 studies included in this review were conducted in the period from 1984 to 2018. The studies were from Europe (7), the USA (13), and non-Western countries (18) (Table 1). Thus, different national or cultural contexts were covered. Except for one, which was a paper from a peer-reviewed research conference, all studies were published in peer-reviewed journals. The results included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies. Most often, students or former students were respondents, but in five studies, teacher bullying was studied from the teacher’s perspective. In 4 studies, both teachers and students were respondents.

Thirty-two of the 38 studies used quantitative methods, like surveys (e.g., Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Benbenishty et al., 2018; Chen & Wei, 2011a, b; Theoklitou et al., 2011). Three studies used qualitative methodology through observation and interview (Hepburn, 2000), case study (Krugman & Krugman, 1984), and focus group discussion and interview (McEvoy, 2005). Three studies used mixed methods with surveys in combination with case studies (Hyman et al., 1988; Shumba, 2002) or interview. (Zerillo & Osterman, 2011). Two studies had a longitudinal design (Brendgen et al., 2006, 2007) and six studies were retrospective (Fromuth, 2015; Hyman et al., 1988; McEvoy, 2005; Monsvold et al., 2011; Shumba, 2007; Whitted & Dupper, 2008).

Among the 38 studies reviewed, 12 used bullying as a main concept. Other studies used the terms abuse (11), maltreatment (6), victimization (6), or violence (3). When reporting the results, the terms used in the particular studies are used here. In the “Discussion” section, we use the term teacher bullying. Regarding the studies that used bullying as the term, 7 studies did not provide a definition. In one study, respondents were introduced to this definition: a pattern of conduct rooted in a power differential that threatens, harms, humiliates, induces fear, or causes students substantial emotional distress (McEvoy, 2005). Two studies utilized another definition for the purpose of the studies: a bullying teacher is a teacher who uses his/her power to punish, manipulate or disparage a student beyond what would be a reasonable disciplinary procedure (Twemlow & Fonagy, 2005; Twemlow et al., 2006). Finally, two studies used adapted versions of the Olweus Questionnaire (Datta et al., 2017; James et al., 2008).

There are 22 studies in our review which reported on the prevalence of teacher bullying, 23 covered the topic of types of teacher bullying, 30 studies reported risk factors for perpetrating teacher bullying, 17 focused on consequences of teacher bullying, and 3 of the studies included the topic responses and measures. The findings are elaborated below separately for each category.

Prevalence

Of the 22 studies reporting prevalence, 20 investigated the extent to which students were exposed using students as informants, while two studies used teachers as informants to investigate how widespread bullying students is among teachers. Overall, the prevalence of bullying was examined in very different ways, within 18 nationalities with different school cultures and with a mixture of retro, current, and longitudinal perspectives. The studies have also been conducted within different times for a period of 34 years (Benbenishty et al., 2018; Krugmann & Krugmann, 1984). These factors may explain why the 22 studies show such a large variation, considering the extent of teacher bullying. The following sections provide an overview of the results.

Prevalence as Reported by Students

The 20 studies that investigated prevalence among students were self-reported. The range of variation for the studies was from 0.6 to almost 90%. The lowest prevalence rate of teacher bullying was found in a Swedish study where students in secondary and upper secondary school reported being bullied by adults at school (Modin et al., 2015). This study examined how different types of bullying are related to psychosomatic health complaints among adolescents. Students were asked if they had felt bullied or harassed at school, with a possibility to pick the alternative “Teachers have psyched me or been mean to me in other ways.” Results showed that 0.6% of the students had experienced teacher bullying. However, the researchers considered the actual number to be somewhat higher because students who reported being bullied by both students and teachers were not included in the survey calculation. Another three studies from European countries showed various prevalence rates. A study conducted in Ireland examined bullying between students and teachers at two time points. Thirty percent of students said they were bullied by teachers at both time points (James et al., 2008). However, the study revealed considerable variations between the forty-one schools that participated, from zero to more than 50%. Theoklitou et al. (2011) found that 22.1% of Cypriot students in 4th to 6th grade experienced abuse from teachers usually or very often.

A study of ninth graders conducted in Flanders in northern Belgium revealed that students experienced both nonethnic and ethnic victimization from teachers, with a prevalence of almost 36% nonethnic victimization and 28% ethnic victimization (D'hondt et al., 2015). We identified eight studies from Israel that report students’ experience with teacher bullying (Benbenishty et al., 2018; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Elbedour et al., 2013; Khoury-Kassabri, 2006, 2009; Khoury-Kassabri et al., 2008). All of these studies showed that Israeli students experienced emotional or psychological forms of bullying behavior from teachers to a higher degree than physical forms. For example, 16% of Jewish religious students reported that teachers emotionally victimized them once or more often during the previous month, while physical forms of bullying behavior varied from 6.3 to 12% within different cultural groups (Benbenishty et al., 2018). Another example is a study by Khoury-Kassabri et al. (2008) that explored whether levels of victimization by school staff towards 4th to 11th graders changed over four points in time from 1998 to 2005. The results revealed that the reported prevalence of victimization was quite similar across the four waves of data collection. In 1998 and 2005, 26.5% and 28.3% of students reported that they experienced emotional victimization from school staff during the previous month. The prevalence of physical maltreatment was 12.5% and 14.9%.

From Asia and Australia, we identified five studies that examined the prevalence of experienced teacher bullying behavior. In a study from Yemen that examined emotional abuse towards children by school staff (Ba-Saddik & Hattab, 2012), 10 to 15% of students experienced being shouted at, humiliated, or nicknamed by school staff five times or more during their time in school. Chen and Wei (2011a, b) studied the prevalence of student victimization by teachers in junior high schools in Taiwan. Overall, the study revealed that almost 30% of the students reported having been maltreated by teachers at least once in the last semester. Lee (2015) investigated the prevalence of emotional and physical maltreatment by teachers in South Korea. He found that almost one-third of the respondents experienced either emotional or physical maltreatment by teachers at least once during the previous year. In an Australian secondary school survey, results showed that 10% of boys and 7% of girls often, rather than never or seldom, were picked on by teachers (Delfabbro et al., 2006).

Four American studies that examined prevalence of teacher bullying behavior were identified. Datta et al. (2017) revealed that 1.2% of students experienced bullying by teachers once a week or more during the current school year. Fromuth et al. (2015) studied features of psychological maltreatment by teachers of students from kindergarten through 12th grade in the USA. The respondents were adults at the time of the survey, who retrospectively looked back at their negative experiences with teachers. The researchers found that 41% experienced more than ten such incidents in a year. However, at the highest rate, a study conducted at an American alternative school for students with behavioral problems, 50 students reported victimizations by teachers or other adults during their total school career (Whitted & Dupper, 2008). Eighty-six percent reported at least one incident of adult physical maltreatment and 88% reported at least one incident of adult psychological maltreatment in school. The study showed that several incidents of maltreatment occurred four times or more often during their school careers. For example, 10% of the students had been hit by the teacher or had things thrown at them more than four times. As many as 36% had been yelled at more than four times. At the time of the survey, the students were attending an alternative school, but their experiences of teacher bullying could be derived from when they attended mainstream school. Students were also asked to describe their “Worst School Experience” (WSE), and 64% stated that an adult was involved in their WSE. WSE was also measured by Pottinger and Stair (2009) in Jamaican schools. This study indicated that educators were responsible for 44% of the incidents that students perceived as their WSE.

Prevalence as Reported by Teachers

We identified only two studies that examined the extent to which teachers report bullying perpetrated by themselves or by colleagues or school staff. One of these studies used self-report, while the other used both self-report and peer (teacher) report. Khoury-Kassabri (2012) revealed that 33.8% of homeroom teachers in Israel reported that they had used physical violence, and one-fifth had used emotional violence towards students in the last month.

Twemlow et al. (2006) studied teacher bullying from teachers’ perspective. In this study, teacher bullying was defined as teachers who abuse their power to punish, manipulate or disparage a student beyond what would be a reasonable disciplinary procedure (p. 191). The study showed that most teachers know that teacher bullying is happening, but mainly as isolated cases. However, 18% of the teachers in the sample stated that teacher bullying occurs on a regular basis. As many as 45% of teachers in this sample admitted that they had bullied a student at least once.

Types of Teacher Bullying

Consistently across countries and school contexts, students experience physical, verbal, psychological, and/or emotional forms of bullying behavior from teachers. Of the 23 studies that examined types of teacher bullying, we found reports of both physical and psychological incidents. Examples of physical incidents are being denied permission to go to the bathroom, being beaten, having one’s ear twisted, and being pushed or shaken (Elbedour et al., 1997; Whitted et al., 2008). Examples of psychological incidents performed by teachers are unfairness and discriminatory practices or the fact that some students receive less attention and are ridiculed, ignored, or isolated. Teachers use nicknames or various forms of threats, coercion and punishment, or comment on the student or the student’s family in derogatory and hurtful ways (James et al., 2008; Monsvold et al., 2011; Whitted et al., 2008). It seems that teacher bullying most often takes place in the classroom with other students present (Elbedour et al., 1997; Zerillo & Osterman, 2011).

Risk Factors at Individual Levels

Of the 30 studies identifying risk factors, we found 19 that identified risk factors at the individual level of students, such as students’ gender, aspects related to age, and aspects related to behavioral problems. Half as many involved individual-level factors regarding teachers, including teachers’ age, gender, and professional/educational level, in addition to teachers’ characteristics, attitudes, and beliefs. One study, which might also be said to concern individual-level factors, focused on both teachers and students; specifically, it pointed to poor student–teacher relationships as a risk factor.

Gender of Students

Of the 19 studies identifying gender as an individual risk factor, 14 concluded that boys are at higher risk than girls (Ba Saddik & Hattab, 2012; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Benbenishty et al., 2018; Brendgen et al., 2006; Brendgen et al., 2007; Chen & Wei, 2011a, b; Delfabbro et al., 2006; Khoury-Kassabri, 2006; Khoury-Kassabri et al., 2008; Khoury-Kassabri, 2009; Lee, 2015; Theoklitou et al., 2011; Yen et al., 2015). However, three studies showed a higher prevalence among girls (Datta et al., 2017; Elbedour et al., 2013; Modin et al., 2015), especially regarding verbal abuse and neglect (Ali et al., 2012). James et al. (2008) and Chen et al. (2011) found no significant gender differences.

Aspects Related to Students’ Age

In the eight studies reporting age or school grade as a risk factor, the data show inconsistent results. However, most studies point to adolescence as the most vulnerable time. Benbenishty et al. (2002a, 2002b) and Monsvold et al. (2011) found that teacher bullying is more prevalent among younger students, while Khoury-Kassabri (2006) and Theoklitou et al. (2011) found no age differences. The remaining four studies found that there is a higher risk of bullying by teachers in adolescent groups (Ba Saddik et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2011; Elbedour et al., 2013; Fromuth et al., 2015).

Aspects Related to Students’ Behavioral Problems

Six studies focused on behavioral problems as a risk factor. Students with behavioral problems, such as attention disorder, antisocial, violent or threatening behavior, or being both a bully and a victim, were found to be at risk for exposure to teacher bullying (Brendgen et al., 2006, 2007; Khoury-Kassabri, 2009, 2012; Yen et al., 2015). Additionally, bully victims reported teacher harassment more often than other students (Yen, 2015). Khoury-Kassabri (2009) also found that bully victims had the highest levels of maltreatment from teachers.

Aspects Related to Teachers’ Gender, Age, and Professional/Educational Level

Few papers have explored how teachers’ gender or number of years of working experience are related to the bullying of students. Only six studies mentioned this in some form, and two of them (Theoklitou et al., 2011; Khoury-Kassabri, 2012) found no gender differences. The other studies had different results. Shumba (2002) revealed that most teacher trainees and teachers believe that female teachers are those who emotionally abuse students. In 2007, Shumba found that male teachers were more verbally abusive (e.g., name-calling and labeling), while female teachers were more likely to show verbal aggression, such as shouting at students. Pottinger et al. (2009) also found that male educators were more abusive than female educators.

With regard to years of experience and educational level, this was addressed in only two studies, both of which found that bullying was more frequent among teachers with 5 or more years of teaching experience (McEvoy, 2005). Khoury-Kassabri (2012) found that the higher the education of teachers, the more they used physical violence.

Aspects Related to Teachers’ Characteristics, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Seven studies considered teachers’ characteristics, attitudes, and beliefs as risk factors. Three of these focused on the fact that specific types of teachers bully others, four studies concerned the misuse of power and/or authority (including classroom management), and one pointed to a low level of self-efficacy among teachers.

Regarding teachers’ characteristics, McEvoy (2005) studied patterns of teachers who bully students in a pilot study through focus group discussions with school staff and interviews with students about their experiences with high school teachers whom they perceived as bullies. The results from the interviews suggested that teachers who are perceived as bullies have rather clear bullying traits. Most of the students agreed that certain teachers bullied students. The school staff also believed that colleagues who bully students are readily identified within the school, and they suggested that it might be common for schools to have one or more teachers who behave in “mean” ways towards students. Twemlow et al. (2006) found that teachers describe colleagues who bully students as two different types. First, the sadistic bully type constitutes a small proportion. These teachers were perceived among colleagues as teachers who humiliate a few selected students, hurt their feelings, and are spiteful to them. The second type, the bully victim type, includes teachers who are frequently absent, fail to set limits, and let others handle problems. The study also revealed that teachers who experienced bullying themselves when they were young were more likely to bully students and experience bullying from students. Zerillo et al. (2011) studied teachers’ perceptions of teacher bullying, focusing on the misuse of power/authority. They found that teachers characterized bullying depending on the consequences for the students rather than the form of the bullying behavior. They identified two types of teacher bullying: denial of access and belittling. Denial of access involved behavior in which the teacher denied services or attention, such as refusing to allow students to use the bathroom, excluding students from assembly programs, and ignoring students who requested help. Teachers perceived denial of access as serious abuse that harms students physically, socially, and emotionally. They also felt that teacher bullying sets a tone that leads peers to model the teacher’s actions and engage in peer bullying. Belittling describes teacher behaviors that most often occur in front of the whole class, such as throwing something at a student or calling students pejorative names. Teachers regard bullying that causes physical harm as more serious than bullying that has social, emotional, and relational effects. Bullying between peers is considered more serious than teacher bullying.

Among teachers, there may be different perceptions of what good quality classroom management is. Hepburn (2000) found that teachers tend to normalize their own negative behaviors related to what is needed to deal with difficult students and to prevent students from harming themselves or harming others. Teachers in this study stated that students often misunderstood situations and negative actions and that they did not distinguish between teachers’ control and bullying behaviors. In a focus group interview (Zerillo et al., 2011), it was found that some teachers justified certain classroom management practices, while other colleagues perceived the same practices as offensive or humiliating behavior.

Khoury-Kassabri (2012) also found a possible connection between bullying behaviors by teachers and classroom management. She examined the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and violence towards students as mediated by teachers’ attitudes. In her study, one-fourth of teachers reported that they needed training to prevent and deal with school violence and that the higher teachers’ efficacy in handling behavioral and emotional problems was, the lower the prevalence of violent teacher behavior. Teachers seem to defend the use of violence when a student uses violence, causes discipline problems, or makes threats. In contrast, teachers who are more reflective reported that bullying is a hazard of teaching and that all people bully at times and are victims and bystanders at times (Twemlow et al., 2006).

Aspects Related to the Student–Teacher Relationship

Having poor relationships with teachers and feeling socially or academically alienated at school are risk factors for experiencing teacher bullying. Chen et al. (2011) found that among all predictors of exposure to teacher victimization, poor-quality student–teacher interaction was the best predictor. Khoury-Kassabri (2006) also found that children who perceived their relationships with teachers negatively were subjected to more staff maltreatment than other students.

Risk Factors at the Contextual Level

Studies that consider risk factors at the contextual level include studies focusing on families with low socioeconomic status and family education level in addition to macro aspects such as being a minority and/or religion and culture.

Socioeconomic Status and Family Education Level

Seven studies mentioned living in families with low socioeconomic status or low educational level as risk factors. Ba Saddik et al. (2012) found that boys who lived in an extended family and had a male parent with low education were at greater risk of being bullied by teachers than others. Benbenishty et al. (2002a, b) found that schools in areas where the population mostly had low education and low socioeconomic status were more likely to have incidents of teacher bullying than schools in more privileged areas. Lee (2015) also found a higher prevalence of teacher bullying towards students from families with low socioeconomic status, and Brendgen et al. (2007) found that boys from these families were at greater risk than girls.

Benbenishty et al. (2002a, b) and Brendgen et al. (2007) found that students from families with lower socioeconomic status or lower economic levels were at higher risk. In Israel, if these students were Arab boys or male students at Arab schools, the risk of teacher bullying was higher than that of Jewish students (Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b).

Minority, Religion, and Culture

The existing literature on teacher bullying that focuses on minority, religion, and/or culture as risk factors is scarce; only 5 studies were found. Only one of the studies compared “white” and different minority groups (Datta et al., 2017). In this study, minority students (e.g., Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and multiracial) were found to report being bullied “by teachers or other adults at school this year” more often than white students; however, the difference was not large. Three studies concerned aspects related to ethnic and religious groups in Israel, namely, the Arab minority group, which was compared to the Jewish majority group. Attending a religious or nonreligious school was also included as a variable. Benbenishty et al. (2002a, b) and Khoury-Kassabri et al. (2008, 2012) found that Arab students reported more maltreatment (both emotional and physical during the last month) by teachers than Jewish students. Additionally, Elbedour et al. (2013) found teacher bullying towards Bedouin Arab students in Israel to be seven times higher than for the mainstream Jewish community. The findings of Arab groups as vulnerable relate to both religion and culture, including cultural beliefs (Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b). Regarding not only the type of religion but also religion vs. nonreligion, children in religious schools report higher incidences of staff maltreatment than children in nonreligious schools; however, this does not exceed the level for children in Arab schools.

Consequences

Seventeen of the identified studies considered the consequences of teacher bullying. These studies show that being exposed to teacher bullying can adversely affect a child’s physical and mental health, participation in education and working life, and sense of well-being in adulthood. Krugman and Krugman (1984) were probably the first to document this phenomenon. They described the observations of seventeen children who were emotionally abused by their elementary schoolteacher during the fall of 1982. It was revealed that during this period of their school career, these third- and fourth-grade children developed behavioral and personality changes that were noticeable to their parents. These changes were characterized by symptoms of anxiety, negative self-perceptions and school belonging, depression, and various psychosomatic symptoms.

Monsvold et al. (2011) found that a group of patients diagnosed with personality disorders reported having experienced significantly more teacher bullying in primary and secondary school than a control group of healthy individuals. A larger proportion of patients also lacked higher education and were excluded from working life. Twemlow et al. (2006) examined the relationship between being bullied as a child and bullying students in the teacher role as an adult and found a significant strong positive correlation between the two variables.

Delfabbro et al. (2006) showed that being exposed to bullying from teachers can result in several negative consequences, including lower self-esteem, withdrawal and social isolation, and generally impaired mental health. In addition, this study found that students who are subjected to bullying by teachers significantly more frequently than other students exhibit high-risk behaviors such as using tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. These students have poorer learning outcomes and a weakened desire to complete their schooling.

Datta et al. (2017) documented that students who are exposed to teacher bullying have greater problems with academic achievement and school adjustment than students who are bullied only by peers. Students from families with low socioeconomic status fared especially poorly. Being exposed to teacher bullying can lead to lower school engagement and a negative perception of the school environment, with little adult support and good order and discipline structures.

Modin et al. (2015) found that Swedish students who reported bullying from teachers significantly more often than other students had psychosomatic complaints such as headaches, sadness, anxiety, poor appetite, stomach problems, and sleep problems. A few studies have investigated how teacher bullying might influence bully victims. Specifically, Yen et al. (2015) found that teacher harassment influenced mental health problems among adolescent bully victims in Taiwan.

Fromuth et al. (2015) examined students’ experiences of exposure to various types of negative actions by teachers. Almost half of the students stated that they almost immediately lost the desire to attend school and developed a hatred for the school. Just under 40% developed low self-esteem, and for a third, the negative actions led them to self-blame. However, it is interesting to note that negative treatment from teachers led to well over half of the students learning to stand up for themselves and being motivated to work harder. At the same time, the study showed that in the long term, most students experienced relationships with teachers as poor. Their perceptions of school developed negatively and had a negative impact on their life in general.

D’Hondt et al. (2015) examined the relationship between the teacher bullying of minority language students and school attachment. Previous studies show that being bullied generally has a negative impact on a strong school affiliation (Demanet & Van Houtte, 2012; Faircloth & Hamm, 2005), which was confirmed by D'Hondt et al. (2015). They examined both bullying in general and ethnic bullying in their study of 15- and 16-year-olds and found that both types of bullying had a negative impact on their sense of belonging at school, but ethnic bullying had the most negative effect.

Responses and Measures

Only three studies included in this review explored how those witnessing incidents of teacher bullying responded to it or whether there were any intervention programs, guidelines, or procedures for dealing with such negative behaviors. Zerillo et al. (2011) found that colleagues who observed teacher bullying intervened in four ways. Most often, they intervened by mediating a remedy for bullying actions, followed by offering support for the victimized student, conferring with the student, and teaching the student coping strategies. Almost one-fifth spoke to an administrator or sought advice from a colleague or union representative. Most of the experienced teachers reported that they would intervene with the bullying teacher, while those with less teaching experience and time employed in the district would seek advice from a colleague.

McEvoy (2005) asked students whether they believed that teachers who bullied students could get into trouble: 77% said yes and 21% said no. The students were also asked whether anything was done to officially reprimand teachers who behaved in abusive ways towards students: 20% said yes and 80% said no. There seemed to be a common belief that most teachers who are perceived as bullies will not be held accountable.

Fromuth et al. (2015) asked students about the education they received regarding bullying and teacher relationships. Almost three-quarters of participants reported having had some education on bullying in schools, but less than 20% reported that it addressed teacher bullying. Less than one-third reported that they had received education about proper and improper relationships between teachers and students.

Discussion

Based on the studies included in this review, teacher bullying occurs within school contexts all over the world in various ways and to various extents. The prevalence rates of bullying behaviors from school staff towards students vary from 0.6 to almost 90%. As previously mentioned, this wide variation can be explained by the fact that the studies were conducted with different measurements at different times in countries with different cultures and different school contexts. Respondents and methods for gathering data varied. Studies also used various definitions of bullying, while some did not define bullying at all. Another problem related to measuring prevalence rates is how these studies differ in the given information about the “cutoff point” and what it is considered exposure to bullying. Some studies used only yes/no to questions about bullying behaviors, whereas other studies asked about frequency. Of course, the percentage becomes much higher at a liberal cutoff point than when two to three times a month or more often are used. The interpretation problem is greatest when the cutoff point is not stated. However, a possible conclusion is that bullying from teachers towards students happens and must be taken seriously, although the prevalence differs according to context and methods used for data collections.

Prevalence and Risk Factors

We identified only two studies that explored the prevalence of teachers who bully using teachers as respondents with reference to how often they perceived themselves or their colleagues as bullies (Khoury-Kassabri, 2012; Twemlow et al., 2006). Another study referred to students’ common perceptions of which teachers were bullies (McEvoy, 2005). These three studies confirmed agreement between teachers and students that a few teachers are identified and known as teachers who intentionally behave in a hurtful way towards some students on a regular basis. However, based on teachers’ self-reported incidents of verbal, physical, or emotional abuse, it is possible to argue that there is always a risk that teachers may hurt students. This underlines the importance of teachers’ ability to be sensitive to students’ needs and feelings in their professional practice and to increase collective awareness of this topic.

Our review clearly indicates that male students in lower secondary school are at a higher risk of being bullied by a member of the school staff. The data do not provide specific reasons for this phenomenon other than suggesting that boys in this age group might be noisier, physically unsteady, and perhaps more bored with school.

Children and youth from families with low income and low educational level are at risk of encountering many negative experiences in their lives (Ba Saddik et al., 2012; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b; Brendgen et al., 2007). Previous studies indicate that school can also be a risk factor in some of these children’s lives (e.g., Chen et al., 2011; Khoury-Kassabri, 2006). Studies show that teacher bullying is likely to occur in situations where students misbehave and the teacher is unable to control or stop the behavior (Hepburn, 2000). It is likely that students from poorly educated and less educated families have many stress factors in their lives that make it more difficult for them to adjust to school. An important aspect regarding risk factors is the interrelation between, for example, minority status, religion, and culture, on the one hand, and SES and other family characteristics, on the other. The Arab minority group in Israel, compared with the Jewish majority, is characterized by high rates of poverty and unemployment; however, the differences between these ethnic/religious groups are also found to be significant after controlling for poverty rates (Benbenishty et al., 2002a, b). Thus, it is also possible that the culture, language, and ways of behavior that these students are familiar with from their home environment are very different from those of the schools. This can be confusing and difficult and might lead to frustration and misbehavior that teachers find difficult to handle. Additionally, adults in some culturally traditional groups approve of punishment because they believe it is an effective way to educate, discipline, and raise children (Khoury-Kassabri et al., 2008).

To summarize, possible risk factors concerning aspects related to teachers may be understood from two perspectives. First, there is a value or ideological perspective that is rooted in teachers’ beliefs about what constitutes good classroom management and education. Second, there are risks related to teachers’ abilities to handle levels of classroom stress in relation to large class sizes and high levels of behavior problems among students (Khoury-Kassabri et al., 2008).

According to the study of Twemlow et al. (2006), bullying can be seen as an attitudinal characteristic derived from negative dynamics of force and power established in childhood. Therefore, being bullied in childhood could constitute a risk factor for teachers to act and respond negatively in their interactions with students, especially if they perceive that their authority as teachers is challenged. In addition, these researchers found that reflective teachers could perceive bullying as a hazard of all teaching, believing that all people bully at times and are victims and bystanders at times. Based on this, it is possible to perceive poor teacher education and poor professional development as contextual risk factors for bullying behavior to occur. If teacher training fails to prepare teachers to prevent and deal with behavioral problems, it is more likely that teachers will act in harmful ways towards students when trying to handle problems in class.

Another possible risk factor for teacher bullying might be related to teachers’ assessment of how harmful their own and their colleagues’ actions are for students. There is a tendency for teachers to consider their actions less negative and less serious than students perceive them. This form of trivialization may be related to teachers’ classroom management styles (James et al., 2008; Zerillo et al., 2011).

Types of Bullying and Consequences

The results of this study makes it possible to conclude that teacher bullying is an international problem. It is also clear that these behaviors have both emotional and physical forms. The repertoire of negative behaviors is plentiful, and these behaviors often occur in front of the class or in other school situations that involve bystanders (Elbedour et al., 1997; Zerillo & Osterman, 2011). The presence of bystanders increases the vulnerability of students exposed to bullying, but for those who witness bullying, it may be harmful to see that someone they care for is violated (James et al., 2008). This can create a class culture of dissatisfaction and anxiety. With reference to the two teacher bully types (Twemlow et al., 2006), both types may harm students intentionally. Some teachers might dominate their students because of a fear of being victimized themselves or feeling envious of smarter students (Twemlow et al., 2006). The bully victim type seems to be more motivated to act in harmful ways because they dislike certain students, such as minorities or students who they perceive as behaviorally challenging (Datta et al., 2017; Elbedour et al., 2013; Twemlow et al., 2006).

Ethnic bullying has a negative impact on students’ sense of belonging at school (D’Hondt et al., 2015). This is in line with attribution theory, suggesting that when people cannot change the reason they are being bullied, they experience it more negatively compared to when they think they can change the underlying cause of bullying (Bellmore et al., 2004; Graham, 2005). Laws in many countries, such as Israel (Khoury-Kassabri, 2012), ban corporal punishment, but few countries have the same strict rules for bullying or verbal insults as Norway (Norwegian Education Act, 1998), which maintains serious consequences for those who perpetrate bullying; criminal prosecution may be the result.

Responses, Measures, and Practical Implications

We identified only three papers that gathered data about how colleagues or students respond to teacher bullying (Fromuth et al., 2015; McEvoy, 2005; Zerillo et al., 2011). Teachers’ power and authority can make it very difficult for fellow students to intervene, and for those who are exposed, notifying someone can be challenging (James et al., 2008). Teachers’ perceptions of seriousness and their intention to intervene in bullying situations depended on whether they felt responsible themselves (Zerillo et al., 2011). The results indicate a great lack of adopted and clear guidelines and procedures for teacher bullying prevention and how students, teacher colleagues, and school leaders should act if they observe or know that teachers are bullying. We can assume that this contributes negatively to the school climate, leading both students and employees to feel unsafe and unsure whom to speak with about solving a problem that is likely devastating for their learning, health, and development. The topic should first be addressed in practical work, that is, the need for clear procedures and guidelines should be emphasized when designing intervention programs. This is also an important topic for future research on intervention research designs.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

We limited our review to studies published in peer-reviewed international journals, which reflect a certain level of quality of the paper. However, excluding studies that are not represented in the peer-reviewed literature might lead studies that are relevant to be overlooked. For example, a study from the Institute for Social Psychology and Understanding in Washington, USA, with a nationally representative sample showed that in 25% of religious-based bullying cases involving Muslim students, a teacher or administrator at school perpetrated bullying (Ansary, 2018). Although this seems to be a relevant study, it is challenging to determine its scientific merit when it is not represented in a peer-reviewed journal and thus reviewed in a systematic way. In addition to using “published in a peer-reviewed journal” as an inclusion criterion, future reviews should consider the research methods used in the selected papers, when possible, with the aim of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the research methods in relation to the state of the field.

This review is also limited to papers in journals in the Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, or English languages. Thus, we might have missed relevant studies published in other languages.

Moreover, the well-established definition of bullying on which this review is based may not exactly fit all teacher behavior that is covered in the selected literature. To identify all relevant existing research on the topic of teacher bullying, we included keywords in our search that describe actions related to bullying but that might be interpreted as wider concepts. We used a combination of 11 keywords in our literature search. The use of a wider range of concepts in our search strategy might have included behavior that does not exactly fit the traditional definition of bullying. Moreover, there might be incidents of racism, discrimination, corporal punishment, and sexual harassment or sexual abuse between school staff and students at school. These concepts also represent serious and unacceptable behaviors and could have been included in the present review. These keywords may be relevant for future reviews.

The inclusion criteria for this review included studies that explored bullying behavior towards students performed by teachers or other school staff within the school context. Thus, teacher bullying refers not only to teachers but also to any other employees within the school context. Bullying by teachers in the classroom context may also be related to subject didactics such as content of and activities in the teaching. There seems to be a gap in the literature regarding this connection; thus, there is a special need for future studies focusing on this topic. In addition to studies focusing on the classroom context, school as a wider context is important; aspects related to school culture should be investigated further.

Some studies indicate the serious impact teacher bullying has on those involved. This is a matter that should be further explored. It is also possible that being bullied by a teacher makes a student more vulnerable for being bullied by peers.

One study showed that students from families with low socioeconomic status are more often targets of teacher bullying than more privileged students. Students from low-income families can be vulnerable in many ways, so this is an area for further research. The gender topic may also be an issue, as boys seem to be more targeted than girls.

Although some minority groups were covered in our selected literature, we might have missed some specific important groups by not including concepts such as racism and discrimination. Thus, gaps in knowledge identified from the results of this review include not only minority groups but also other vulnerable groups, such as groups with different disabilities, which should be studied in greater depth in future research.

To the best of our knowledge, our review is the first conducted on the topic of teacher bullying. More studies are needed to complement the existing literature to further expand our understanding of the current state of this important topic.

References

Ali, T., Ashraah, M., & Al-swalha, A. (2012). The degree of adolescences’ perception towards types of abuse they received from their teachers and its relation to their self-concept. International Journal of Academic Research, 5(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.7813/2075-4124.2013/5-1/B.5

Ansary, N. S. (2018). Religious-based bullying: Insights on research and evidence-based best practices from the National Interfaith Anti-Bullying Summit (2017), https://www.ispu.org/religious-based-bullying-insights-on-research-and-evidence-based-best-practices-from-the-national-interfaith-anti-bullying-summit/

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2007). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Ba- Saddik, A. S. S., & Hattab, A. S. (2012). Emotional abuse towards children by schoolteachers in Aden Governorate, Yemen: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 647. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-647

Bellmore, A. D., Witkow, M. R., Graham, S. & Juvenin, J. (2004). Beyond the individual: The impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioural norms on victim’s adjustment Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159

Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., López, V., Bilbao, M., & Ascorra, P. (2018). Victimization of teachers by students in Israel and in Chile and its relations with teachers’ victimization of students. Aggressive Behavior, 45(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21791

Benbenishty, R., Zeira, A., Astor, R. A., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2002a). Maltreatment of primary school students by educational staff in Israel. Child Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00416-7

Benbenishty, R., Zeira, A., & Astor, R. A. (2002b). Children’s reports of emotional, physical and sexual maltreatment by educational staff in Israel. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(8), 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00350-2

Brendgen, M., Wanner, B., & Vitaro, F. (2006). Verbal abuse by the teacher and child adjustment from kindergarten through grade 6. Pediatrics May 2006, 117(5) 1585–1598. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2050

Brendgen, M., Wanner, B., Vitaro, F., Bukowski, W. M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2007). Verbal abuse by the teacher during childhood and academic, behavioral, and emotional adjustment in young adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.26

Chen, J. -K., & Wei, H. -S. (2011a). The impact of school violence on self-esteem and depression among taiwanese junior high school students. Social Indicators Research, 100(3), 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9625-4

Chen, J. -K., & Wei, H. -S. (2011b). Student victimization by teachers in Taiwan: Prevalence and associations. Child Abuse & Neglect: The International Journal, 35(5), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.009

Convention of the rights of the Child. (Nov. 20. 1989). 1577 U.N.T.S. 3. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/

Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504

Crosson-Tower, C. (2009). Understanding child abuse and neglect (8th ed.). Pearson.

Datta, P., Cornell, D., & Huang, F. (2017). The toxicity of bullying by teachers and other school staff. School Psychology Review, 46(4), 335–348. Academic Search Premier. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0001.V46-4

D’Hondt, F., Van Houtte, M., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2015). How does ethnic and non-ethnic victimization by peers and by teachers relate to the school belongingness of ethnic minority students in Flanders, Belgium? An explorative study. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 18(4), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9304-z

Delfabbro, P., Winefield, T., Trainor, S., Dollard, M., Anderson, S., Metzer, J., & Hammarstrom, A. (2006). Peer and teacher bullying/victimization of South Australian secondary school students: Prevalence and psychosocial profiles. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904X24645

Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: The differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9674-2

Elbedour, S., Assor, A., Center B. A., & Maruyama, G. M. (1997). Physical and psychological maltreatment in schools: The abusive behaviors of teachers in Bedouin schools in Israel. School Psychology International, 18(3), 201−215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034397183002

Elbedour, S., ElBassiouny, A., Bart, W. M., & Elbedour, H. (2013). School violence in Bedouin schools in Israel: A re-examination. School Psychology International, 34(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312453388

Faircloth, B. S., & Hamm, J. V. (2005). Sense of belonging among high school students representing 4 ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(4), 293−309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-5752-7

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117(5), 1568–1574. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0187

Fromuth, M., Davis, T., Kelly, D., & Wakefield, C. (2015). Descriptive features of student psychological maltreatment by teachers. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 8(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0042-3

Graham, S. (2005). Attributions and peer harassment. Interaction Studies, 6(1), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1075/is.6.1.09gra

Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal – And truancy related reasons for school non-attendance. Social Psychology of Education., 18(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9293-y

Hepburn, A. (2000). Power lines: Derrida, discursive psychology and the management of accusations of teacher bullying. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164651

Hyman, I. A. (1990). Reading, writing, and the hickory stick. Lexington Books.

Hyman, I. A., Zelikoff, W., & Clarke, J. (1988). Psychological and physical abuse in the schools: A paradigm for understanding post-traumatic stress disorder in children and youth. 25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490010210

James, D. J., Lawlor, M., Courtney, P., Flynn, A., Henry, B., & Murphy, N. (2008). Bullying behaviour in secondary schools: What roles do teachers play? Child Abuse Review, 17(3), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1025

Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2006). Student victimization by educational staff in Israel. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(6), 691–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.003

Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2009). The relationship between staff maltreatment of students and bully-victim group membership. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(12), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.005

Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2012). The relationship between teacher self-efficacy and violence toward students as mediated by teacher’s attitude. Social Work Research, 36(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svs004

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2008). Student victimization by school staff in the context of an Israeli national school safety campaign. Aggressive Behavior, 34(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20180

Kim, Y. S., Leventhal, B. L., Koh, Y. J., Hubbard, A., & Boyce, W. T. (2006). School bullying and youth violence: Causes or consequences of psychopathologic behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(9), 1035–1041. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1035

Krugman, R. D., & Krugman, M. K. (1984). Emotional abuse in the classroom. The pediatrician’s role in diagnosis and treatment. Am J Dis Child, 138(3), 284–286. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140410062019

Lee, J. H. (2015). Prevalence and predictors of self-reported student maltreatment by teachers in South Korea. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.009

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Mc Coy, M. L., & Keen, S. M. (2009). Child abuse and neglect (1st ed.). Psychology Press.

McEvoy, A. (2005, September 11.-14). Teachers who bully students: Patterns and policy implications. [Paperpresentation]. Hamilton Fish Institute’s Persistently Safe Schools Conference. Philadelphia.

Miller-Perrin, C. L., & Perrin, R. D. (1999). Child maltreatment: An introduction (1st ed.). Sage Publications.

Modin, B., Låftman, S. B., & Östberg, V. (2015). Bullying in context: An analysis of psychosomatic complaints among adolescents in Stockholm. Journal of School Violence, 14(4), 382–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.928640

Monsvold, T., Bendixen, M., Hagen, R., & Helvik, A.-S. (2011). Exposure to teacher bullying in schools: A study of patients with personality disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 65(5), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2010.546881

Myers, J. E. B. (2010). The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. (Volume 3) Third Edition. California Sage Publications.

Norwegian Education Act. (1998). Act relating to primary and secondary education and training (LOV-1998–07–17–61). Retrieved from http://lovdata.no/all/nl-19980717-061.html

Olweus, D. (1983). Bullying at school. What we know and what we can do. Blackwell Publishers.

Olweus, D. (1996). Mobbing av elever fra lærere. [Bullying of students by teachers]. Bergen: Alma Mater forlag AS.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews: International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Assosiation. https://doi.org/10.1037/10314-000

Pottinger, A. M., & Stair, A. G. (2009). Bullying of students by teachers and peers and its effect on the psychological well-being of dtudents in Jamaican Schools. Journal of School Violence, 8(4), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220903130155

Roland, E. (1996). Lærermobbing av elever. [Teacher bullying of students]. Norsk skoleblad.

Roland, E. (1999). School influences on bullying. Stavanger: Rebell.

Rueger, S. Y. & Jenkins, L. N. (2014). Effects of peer victimization on psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000036

Shumba, A. (2002). The nature, extent and effects of emotional abuse on primary school pupils by teachers in Zimbabwe. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(8), 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00351-4

Shumba, A. (2007). Emotional abuse in the classroom: A cultural dilemma? Journal of Emotional Abuse, 4(3–4), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v04n03_09

Sjursø, I. R., Fandrem, H. & Roland, E. (2015). Emotional problems in traditional and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.31265/usps.71

Theoklitou, D., Kabitsis, N., & Kabitsi, A. (2011). Physical and emotional abuse of primary school children by teachers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.007

Twemlow, S. W., & Fonagy, P. (2005). The prevalence of teachers who bully students in schools with differing levels of behavioral problems. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(12), 2387–2389. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2387

Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., Sacco, F. C., & Brethour, J. R., Jr. (2006). Teachers who bully students: A hidden trauma. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764006067234

Wendelborg, C. (2020). Mobbing og arbeidsro i skolen. Analyse av Elevundersøkelsen 2019/20. [Bullying and work in peace. An analysis of the National student survey 2017/2018]. (NTNU Rapport). Retrived from: https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/finn-forskning/rapporter/elevundersokelsen-2020--nasjonale-tall-for-mobbing-og-arbeidsro/

Whitted, K. S., & Dupper, D. R. (2008). Do teachers bully students?: Findings from a survey of students in an alternative education setting. Education & Urban Society, 40(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124507304487

World Health Organization. (2020). Identified 5th December 2020 at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

Yen, C. -F., Ko, C. -H., Liu, T. -L., & Hu, H. -F. (2015). Physical child abuse and teacher harassment and their effects on mental health problems amongst adolescent bully-victims in Taiwan. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(5), 683–692. Academic Search Premier. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0510-2

Zerillo, C., & Osterman, K. F. (2011). Teacher perceptions of teacher bullying. Improving Schools, 14(3), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480206061994

Funding

Open access funding provided by University Of Stavanger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gusfre, K.S., Støen, J. & Fandrem, H. Bullying by Teachers Towards Students—a Scoping Review. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 5, 331–347 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00131-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00131-z