Abstract

Introduction

The management of specific clinical scenarios is not adequately addressed in national and international guidelines for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). Expert opinions could serve as a valuable complement to these documents.

Methods

Seven expert rheumatologists identified controversial areas or gaps of current recommendations for the management of patients with axSpA. A systematic literature review (SLR) was performed to analyze the efficacy and safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, conventional synthetic, biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs, b/tsDMARDs) in axSpA regarding controversial areas or gaps. In a nominal group meeting, the results of the SLR were discussed and a set of statements were proposed. A Delphi process inviting 150 rheumatologists was followed to define the final statements. Agreement was defined as if at least 70% of the participants voted ≥ 7 (from 1, totally disagree, to 10, totally agree).

Results

Three overarching principles and 17 recommendations were generated. All reached agreement. According to them, axSpA care should be holistic and individualized, taking into account objective findings, comorbidities, and patients’ opinions and preferences. Integrating imaging and clinical assessment with biomarker analysis could also help in decision-making. Connected to treatments, in refractory enthesitis, b/tsDMARDs are recommended. If active peripheral arthritis, csDMARD might be considered before b/tsDMARDs. The presence of significant structural damage, long disease duration, or HLA-B27-negative status do not contraindicate for the use of b/tsDMARDs.

Conclusions

These recommendations are intended to complement guidelines by helping health professionals address and manage specific groups of patients, particular clinical scenarios, and gaps in axSpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

National and international guidelines in the management of axial spondyloarthritis do (axSpA) not cover all clinical scenarios and patient profiles. |

Expert opinion is a valid tool in resolving uncertainties and controversies of daily practice. |

Given the heterogeneity of axSpA, physicians should carefully evaluate the impact of individual manifestations and comorbidities on patients in order to define the best treatment and treatment strategy. |

Integrating imaging and clinical assessment with biomarker analysis could also help provide personalized medicine in axSpA. |

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the axial skeleton [1]. It comprises radiographic axSpA, previously known as ankylosing spondylitis, and non-radiographic axSpA [2]. AxSpA is characterized by inflammatory back pain, sacroiliitis, bone formation, and a high prevalence of HLA–B27 [1]. Patients with axSpA may also present peripheral manifestations such as peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis, and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (EMMs) like uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and psoriasis [3]. The impact of the disease on a patient’s quality of life is significant [3].

The management of axSpA is based on non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions, depending on patients’ manifestations [4, 5]. Different therapeutic agents are currently available for patients with axSpA such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) like sulfasalazine (SSZ) and methotrexate (MTX), and biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs) including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i), and Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) [4, 5]. Along with medications, non-pharmacological treatment and a treat-to-target (T2T) strategy has been proposed for the management of patients with axSpA [6].

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have played a vital role in assessing the efficacy of these drugs in patients with axSpA. However, there is still a lack of direct comparative studies, which are highly relevant to clinical practice. Besides, taking into account the strict inclusion criteria of RCTs, study populations might not be representative of ‘real-life’ patients and therefore, results lack generalizability.

Consensus documents aim to analyze the best evidence and to provide some guidance in treatment decision-making, including situations where evidence is insufficient or even absent. National and international organizations like The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) have published these types of documents for axSpA patients [7,8,9]. They are typically focused on the most important or frequent patient profiles. However, in daily practice, it is common to encounter difficult-to-treat manifestations or clinical situations that are not explicitly addressed in these documents.

Considering all the above, we designed this expert consensus document to complement the current recommendation articles [7,8,9]. For this purpose, we established the following objectives: (1) to define difficult-to-treat manifestations, particular clinical situations or controversial areas, (2) to collect and analyze the best available evidence by conducting a systematic literature review (SLR), and (3) to generate practical recommendations to guide physicians in the management of axSpA patients. We are confident that this document will aid rheumatologists and other healthcare professionals in making treatment decisions for these patients.

Methods

The nominal group and Delphi techniques were used. The document was generated via distribution of tasks, with the help of a SLR, and under the supervision of a methodologist. This study was conducted following Good Clinical Practice and the current version of the revised Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Declaration of Helsinki). The study was exempt from requiring ethics committee approval in line with national guidelines and rheumatologists provided their informed consent to participate in the Delphi process.

First Nominal Meeting Group

A steering group consisting of seven experts on axSpA was established. The criteria for the selection of experts were: rheumatologists with special interest in axSpA, clinical experience ≥ 8 years and/or ≥ 5 publications on axSpA, and members of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) and/or related working groups on axSpA.

In the first on-line nominal meeting, the steering group established the objectives, scope, users, definitions, and document contents. Also, specific clinical scenarios not fully covered in national and international guidelines, including controversial areas and gaps in axSpA were also identified, e.g., refractory enthesitis (see Table 1). With all this information, the experts defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for a subsequent SLR.

Systematic Literature Review

An SLR was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyzes (PRISMA) guidelines. A protocol of the SLR was then designed. The research question “Which is the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, TNFi, IL- 17i and JAKi, in the specific clinical scenarios identified in the project (Table 1), regarding the management of patients with axSpA?” was translated to a PICO question. Studies were identified using sensitive search strategies in the main medical databases. For this purpose, an expert librarian (MM) checked the search strategies (Supplementary Material). Disease- and treatment-related terms were used as search keywords, which employed a controlled vocabulary, specific MeSH headings, and additional keywords. The following bibliographic databases were screened: Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Library (up to April 2022). Retrieved references were managed in Endnote X5 (Thomson Reuters). The abstracts of the 2021 and 2022 annual scientific meetings of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) were also examined, along with national and international consensus documents and guidelines [7,8,9].

Studies were included if they met the following pre-established criteria. Included patients had to be diagnosed with axSpA, 18 years of age or older, that could be included in the specific clinical scenarios (Table 1), and treated with the selected pharmacological therapies. There was no restriction regarding the type of drug, dose, route of administration, concomitant use of other drugs, or treatment duration. Besides disease activity and function, other outcomes were considered, such as pain, radiographic progression or quality of life. SLRs, RCTs, and high-quality observational studies (including at least 100 patients) in English or Spanish were included.

The screening of studies, data collection, and analysis were performed independently by two reviewers (EL and Chelo Pascau). In the case of discrepancy between them, a consensus was reached by a third reviewer (Loreto Carmona). Study quality was assessed with the AMSTAR-2 for SLRs [10], the Jadad score [11] for RCTs, and the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for observational studies [12] (a summary of the studies quality is shown in the Supplementary Materials). Evidence tables were then produced, and meta-analysis was only planned if homogeneity among the included studies.

Second Nominal Meeting Group

The steering group participated in a second on-line meeting group. Prior to the meeting, the results of the SLR and of a national survey of patients with ax-SpA [13] were distributed. The experts, following the results of the SLR but also based on their experience, formulated several statements for the management of difficult-to-treat manifestations or specific clinical scenarios in axSpA.

Delphi

Statements were subsequently submitted to online Delphi voting. Delphi was extended to a group of 150 rheumatologists all over the country. Participants were selected following two strategies. In a first step, the steering group proposed and invited five clinical rheumatologists without specific interest in axSpA, assuring geographical representation. In a second step, an invitation to participate was sent to the members of GRESSER. GRESSER is a working group of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology that includes health professionals with interest and expertise in the field of SpA. The participants voted for each statement on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 = totally disagree, to 10 = totally agree). Agreement was defined if at least 70% of participants voted ≥ 7. Statements with a level of agreement (LA) inferior to 70% were analyzed and, if appropriate, re-edited and voted in a second round.

Final Consensus Document

After the Delphi, and along with the results of the SLR, the final document was written. The methodologist assisted in assigning each statement, a level of evidence (LE), and grade of statement (GR), according to the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine of Oxford [14]. The document was circulated among the experts for final assessment and comments.

Results

Results of the Systematic Literature Review

Several particular clinical scenarios, controversial areas, or gaps were identified (Table 1). The SLR retrieved 2952 articles of which 132 were finally included – 62 SLR and 70 RCT (Fig. 1). Most of them were studies of good quality. We found evidence regarding NSAIDs, corticosteroids, csDMARDs including SSZ, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, MTX, TNFi such as infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept (ETN), certolizumab pegol, golimumab, TNFi biosimilars, IL-17i like secukinumab (SEC) or ixekizumab (IXE) and JAKi tofacitinib (TFC), and upadacitinib (UPA). The efficacy and safety of these drugs were assessed in different clinical scenarios/areas: refractory enthesitis [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], peripheral arthritis [15, 17, 26,27,28], presence of significant structural damage [29,30,31,32], extramusculoskeletal manifestations [33,34,35,36,37,38], comorbidities [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], risk management [38], treatment stratification and treatment strategies [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], and adherence [59].

Results of the Delphi

A total of 20 statements to guide treatment decisions were generated. The Delphi response rate was 58%. All reached pre-stablished consensus (see Table 2 for more details). Based on identified gaps in evidence, a research agenda was also formulated (Table 3).

We now summarize the findings of the SLR and the experts' opinion across the statements.

Overarching Principles

Statement 1: The therapeutic strategy in axSpA should be holistic, taking into account clinical findings and their impact on patient's daily life (LE 5; GR D; LA 93%).

AxSpA is a potentially severe disease, clinically heterogeneous, in which musculoskeletal and EMMs might produce a significant impact on the patient’s life [3]. Thus, treatment should be adapted to patient’s clinical and personal context and perspective.

Besides, in line with international guidelines and current evidence, it is important to state that axSpA should aim at the best care and must be based on a shared decision between the patient and the rheumatologist. More specifically, the treatment objective must be the achievement of remission or at least low disease activity [7].

Statement 2: Therapeutic decisions should be individualized, informed, and agreed upon with the patient (LE 5; GR D; LA 94%).

Different studies have described patient decision-making surrounding medication options for axSpA [13, 60]. Patients with axSpA usually prioritize medication efficacy, the route of administration, and risks [13, 60]. They have also shown that treatment decision-making is highly individualized, as demographics and baseline disease characteristics are poor predictors of individual preferences [60]. These results underscore the need for a careful dialogue with each patient. Accesible information tailored to the patients’ characteristics and literacy should also be provided. This will enhance communication and optimize selection of therapies in order to improve adherence and outcomes.

Statement 3: In therapeutic decision-making, it is essential to systematically monitor patients’ disease with validated tools (LE 3; GR C; LA 89%).

Several instruments are available for the monitoring of axSpA patients [61,62,63]. The preferred tool of the experts is the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS). This is a validated, highly discriminatory instrument for assessing disease activity in axSpA, including patient-reported outcomes and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Besides, the ASDAS scores has demonstrated better psychometric properties than the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [61].

Musculoskeletal Manifestations

Statement 4: In patients with enthesitis, a clinical history and exhaustive physical examination should be performed to rule out mechanical pain or other problems such as central sensitization of pain, especially in patients with multiple enthesis pain (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

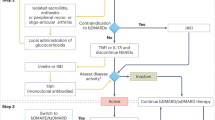

Statement 5: In patients with enthesitis refractory to usual initial treatment (physical measures, NSAIDs, and local infiltrations), it is recommended to consider TNFα, IL-17, or JAK inhibitors (LE 1a; GR A; LA 100%).

Enthesitis is a common symptom of axSpA, occurring with high frequency at axial and several peripheral sites, with a prevalence of 35–60% [64]. Enthesitis is also associated with a significant impact on patients [65]. Therefore, as recommended in national and international consensus, enthesitis assessment should be included in the evaluation of the disease [7,8,9].

However, in daily practice, there are axSpA patients that experience widespread pain, including chronic back pain and tenderness at multiple sites that may mimic enthesitis, for example due to fibromyalgia [66, 67]. In fact, in axSpA cohorts the prevalence of fibromyalgia has been reported in 4–25% [66]. Thus, fibromyalgia or other conditions (e.g., mechanical pain, depression, central sensitization) should be ruled out, especially in patients with multiple enthesitic pain and resistance to multiple treatment interventions [67]. In this context, imaging can be useful in assessing potential underlying inflammation.

On the other hand, the evidence on the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, csDMARDs, TNFi, IL- 17i, and JAKi in patients with enthesitis is quite heterogeneous, at least in part due to different criteria and outcomes measures. There is no robust evidence regarding NSAIDs, but they might be effective [15]. A SLR that included six prospective observational studies showed that local corticosteroid injections can improve clinical and ultrasound enthesitis [16]. Data of csDMARDs are scarce and inconclusive [15, 17]. Finally, the efficacy of TNFi and IL-17i has been depicted in many high-quality trials [18,19,20,21,22], though it is less robust for JAKi [23,24,25].

The experts consider that in routine clinical practice, treatment decisions should be individualized according to the type, location, number of affected enthesis, and associated disability. As a general principle, however, for patients with mild enthesitis, the initial treatment approach could involve physical therapy, NSAIDs, and local corticosteroid injections at the affected site, guided by ultrasound when possible. However, it is important to mention that some guidelines do not recommend peri-tendon injections of Achilles [8]. These treatments can also be considered in high symptomatic/disabled patients as a temporary co-adjuvant treatment.

Statement 6: In patients with stable axial disease presenting active peripheral arthritis/tenosynovitis/dactylitis, csDMARD (SSZ or MTX) might be considered before TNFi, IL-17i, and JAKi (LE 2a; GR B; LA 90%).

For the experts, peripheral arthritis comprises patients with tenosynovitis, dactylitis, oligo and polyarthritis. All of them are considered as a group. Stable axial disease was defined as a disease that was asymptomatic or causing symptoms but at an acceptable level as reported by the patient. A minimum duration of 6 months was necessary to meet the criteria for clinical stability [8].

Among csDMARDs [15, 17], SSZ has demonstrated efficacy in the subgroup of patients with peripheral arthritis [17]. However, there is uncertainty about the efficacy of MTX [15]. Treatment with MTX might be considered for patients with predominant peripheral arthritis, although among csDMARDs, most evidence supports the use of SSZ.

In selected cases of patients with peripheral arthritis (high symptomatic/disabled), local corticosteroids injections [26], or a short-low-dose course of oral corticosteroids, might be considered as co-adjuvant treatments, along with csDMARDs, b/tsDMARDs [27].

It has been published that 25–36% of patients with SpA present hip involvement [26, 28]. Despite a great impact on patients [68], there is no quality evidence regarding the best treatment options. Small observational studies have shown that in the short and long term, TNFi can be effective (disease activity, structural damage and function) [69,70,71].

Statement 7: The presence of significant structural damage does not contraindicate the use of b/tsDMARDs (LE 1b; GR A; LA 100%).

Although “significant structural damage” is not currently defined, in daily practice rheumatologists are faced with patients with advanced disease and important radiographic progression. In the first-published RCTs on TNFi [29], many of the included patients presented substantial advanced disease, according to radiographic baseline data. In these trials, TNFi were effective [30], even in patients with total spinal ankylosis [31, 32]. Data on radiographic progression with the use of IL-17i [54, 72] and JAKi RCT are still scarce, but they might probably be effective in patients with significant structural damage.

Extramusculoskeletal Manifestations

Statement 8: Decisions on patients with EMMs should be made along with the corresponding medical specialist or health professional (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Statement 9: In patients with recurrent non-infectious uveitis refractory to csDMARDs, monoclonal antibodies against TNFα are preferred over other therapeutic options (LE 1a; GR A; LA 100%).

EMMs such as uveitis, IBD, and psoriasis are relatively frequent in axSpA [64]. In order to provide the best care to patients, other medical specialists and health professionals should be involved in the decision-making process [73, 74].

In patients with axSpA and recurrent non-infectious uveitis, monoclonal antibodies against TNFα have been shown to be efficacious in preventing recurrences, whereas ETN have depicted contradictory results [33, 37]. Monoclonal antibodies against TNFα are also associated with a lower uveitis incidence compared with IL-17i [33,34,35,36]. The information is currently insufficient for TFC and UPA, but there are no warning signs in this regard. Taking all these data into account, the experts, in line with other consensus documents [73, 74], recommend monoclonal antibodies against TNFα as the first option.

However, it should be noted that in many R CT, uveitis is not a primary or secondary outcome. It is usually described as an adverse event. In addition, uveitis has not been properly described (type, location, severity, recurrence, etc.).

Statement 10: In axSpA patients with coexistent IBD, monoclonal antibodies against TNFα or JAKi are the preferred options (LE 1b; GR B; LA 90%).

A SLR showed the pooled prevalence of IBD in patients with axSpA to be 6.8% [75]. Similar to uveitis, current data on the efficacy and safety of available therapies are still limited. The rate of IBD in RCTs (and extensions) of TNFi and IL-17i is in general very low and comparable to those of the placebo arm [37, 38]. Biologics registers have depicted similar findings [76]. Long-term data regarding TFC and UPA are lacking, but there are no warning signs so far [23, 25].

On the other hand, in patients with IBD, SEC and monoclonal antibodies against TNFα have demonstrated efficacy (except for ETN) [77,78,79,80]. TFC and UPA have been approved for ulcerative colitis (UC). Several network meta-analyses have shown that TFC is effective for achieving clinical, endoscopic, and quality-of-life outcomes compared to placebo in patients with UC [81]. Recently published RCTs are also obtaining positive results with UPA [82].

Comorbidity

Statement 11: Comorbidity screening and management should systematically be performed in all patients with axSpA (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

The prevalence of comorbidity in axSpA is considerable. The ASAS-COMOSPA study found that the most frequent comorbidities in SpA were osteoporosis (13%) and gastroduodenal ulcer (11%), and the most frequent cardiovascular risk factors were hypertension (34%), smoking (29%), and hypercholesterolemia (27%) [83]. Comorbidity also has an impact on disease activity, functional and work disability, mortality, and has been associated with lower response to treatments [84,85,86]. Thus, it is crucial to increase awareness of comorbidities.

For the experts, rheumatologists should systematically investigate comorbidities and risk factors with high incidence or impact, especially those that may be potentially preventable, but also those that may interfere with the assessment of axSpA or its treatments. The management of comorbidities will depend on the comorbidity, rheumatologists experience, and local organization.

In this context, as a part of comorbidity management, the experts emphasize that healthy lifestyle promotion among axSpA patients is vital.

Statement 12: During the assessment of patients with axSpA, it is recommended to evaluate the cardiovascular risk (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Statement 13: In patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors, if NSAIDs are indispensable, their use should be limited to the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time (LE 1b; GR B; LA 100%).

As shown before, the prevalence and impact of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) or risk factors (CVRFs) in axSpA are not trivial [83], though are lower compared with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis [87]. AxSpA is associated with increased all-cause mortality, especially due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases [88]. Population-based studies have found that CVD accounts for 25–50% of all deaths [88,89,90]. A recent cross-sectional international study did not find a higher prevalence or CV ischemic events in SpA (either peripheral or axial) than that described for the general population [83], likely explained by a younger age in SpA populations. However, it is worth noting that patients with axSpA have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors compared to the general population [83, 86]. CVRFs not only contribute to mortality risk but also to poorer outcomes. Smoking is associated with increased disease activity and structural progression, and poorer treatment response to TNFi [91, 92]. Obesity is associated with significantly lower response rates to TNFi (BASDAI50, ASAS40, BASDAI ≤ 4) in patients with axSpA as well [93]. Not only obesity, but overweight is also significantly associated with a lower response to TNFi treatment [39, 40]. Currently, there is no evidence suggesting the influence of weight on the response to NSAIDs, csDMARDs, IL-17i [94, 95] or JAKi [96].

Thus, CVD risk assessment is recommended for all patients with axSpA at least once a year and should be reassessed if relevant changes in treatment occur. Also, CVD risk estimation should be performed according to national guidelines and the SCORE CVD risk prediction model (adapted to axSpA population) [97].

On the other hand, NSAIDs are the "cornerstone" of axSpA therapy. Connected to the effect of NDAIDS on the risk of cardiovascular events (CVEs) in axSpA patients, NSAID users as a whole and patients on selective COX inhibitors NSAIDs do not seem to clearly have a higher risk of any CVE (including mayor events) [41,42,43]. Some data suggest a lower risk of composite CVE outcome with COX-2 inhibitors, unlike the increased risk described in the general population. However, the certainty in evidence was very low due to the observational and heterogeneous design in most of the studies (different patients’ baseline risk, drug characteristics including NSAID class, doses, treatment duration, etc.). Finally, among NSAIDs, naproxen and low-dose ibuprofen appear to have lower increased CV risk [41,42,43].

Although NSAIDs have demonstrated efficacy in axSpA [41, 98], prescription of NSAIDs should be evaluated on an individual patient level, with caution, especially for patients with documented CVD or in the presence of CVD risk factors. In general, experts tend to favor on-demand NSAID treatment at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration possible if alternative treatments do not effectively manage the patient's inflammatory symptoms. Using continuous NSAIDs might generate other safety problems. Furthermore, the use of NSAIDs should also take into account other factors like a patient’s age, weight, characteristics of the CVD, number and type of CVRF, or the amount of NSAIDs needed to control symptoms.

Several RSLs and meta-analyses, RCTs, and extension studies have shown that csDMARDs, TNFi, or IL-17i are not associated with an increased risk of CVD or CVRFs [21, 34, 35, 41,42,43,44,45]. Data regarding JAKi cardiovascular risk are lacking in axSpA, where the patients’ and disease profiles are quite different from RA studied populations, especially regarding the prevalence of previous CVEs [99]. Therefore, until more data becomes available, TFC and UPA should be reserved for the following patients only when no suitable alternative treatments are available: those aged 65 years and older, those with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or other cardiovascular risk factors, those who are current or former long-term smokers, or those with risk factors for malignancy (e.g., current or previous malignancy). Cautious use is also recommended in patients with known risk factors for venous thromboembolism [99].

Though the reported prevalence of heart failure in axSpA is quite low [100], heart failure can have a significant impact on function and quality of life [101], and also on the optimal treatment selection in patients with axSpA. A significantly higher risk of developing heart failure has been found with the use of NSAIDs [102]. TNFi have also been linked with increased incidence/worsening of heart failure in autoimmune diseases, but this evidence is quite inconsistent [103]. No red flags have been described for other axSpA treatments. Therefore, and in line with the summary of product characteristics recommendations, in patients with New York Heart Association (NIHA) class III or IV heart failure, TNFi and NSAIDs are not recommended.

Osteoporosis is the most prevalent comorbidity in axSpA patients [83]. Inflammation has been associated with increased bone resorption and impaired bone formation, by inflammatory mediators’ action on osteoclast activity. Therefore, there is a rationale to use potent anti-inflammatory drugs [86]. Conflicting results have been reported with the use of NSAIDs [46, 47]. Thus, the effect of NSAIDs on bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture prevention needs to be further explored. The evidence shows that treatment with TNFi over 2–4 years and SEC significantly increases bone mineral density (BMD) at lumbar spine in patients with axSpA, but the effect is unclear at the total hip and femoral neck [48, 49]. However, data are lacking regarding fracture prevention. More evidence is required to assess the role of JAKi on bone metabolism. As fractures have been observed in patients treated with TFC [104], this agent should be used with caution in patients with known risk factors for fractures, such as elderly patients, female patients, and patients using corticosteroids.

Rheumatologists should also be aware of other relevant comorbidities described in axSpA patients like cancer, fibromyalgia, or depression [83]. In recent years, the interest in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has clearly increased [105]. Though more research is needed, taking into account the results in psoriasis, the use of IL-17i might be the preferred over other therapies [106].

At this point, the experts would like to point out, in line with other documents [107], that lifestyle improvements complement pharmacological treatment. There is compelling evidence, despite small individual effects (in some cases), that quitting smoking, practicing regular exercise, controlling weight gain, work participation, and a healthy diet are of additional benefit to axSpA patients [107].

Risk Management

Statement 14: Current evidence does not suggest an increased risk of infections (including serious infections) in axSpA patients when using b/tsDMARDs. However, risk management should be performed, as in other immune-mediated diseases. Thus, risk factors for infection should be assessed (LE 1a; GR A; LA 85%).

Data on infectious risk are still poor in axSpA patients exposed to immunosuppressive drugs. There is some heterogeneity and controversy between the results from RCTs and observational studies, but in general, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest an increased risk of infections or serious infections [19, 38, 108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122].

The reported frequency of serious infections on patients treated with TNFi is low and similar across different TNFi [19, 38, 108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122]. Tuberculosis infection is also uncommon [38]. In this regard, it is important to mention that based on RA experience, multiple preventive activities have been implemented in daily practice [123]. In addition, the characteristics of patients with axSpA are different compared with RA patients (younger age, less use of corticosteroids, and combined therapies, etc.). All of this might explain the reported low rate of serious infection in axSpA.

IL-17i have been associated with an increased risk of mucocutaneous Candida infections, especially oral infections, but most of them are mild and transient [21, 34, 124,125,126].

Regarding TFC, a RCT found five cases (1.86%) of herpes zoster (severe and non-severe) during 48 weeks of treatment [23]. The evidence connected to UPA (15 mg/day) is still preliminary, but only three cases of herpes zoster have been reported up to 64 weeks in three trials [22, 24, 25].

Though infection risk is not currently increased in axSpA, taking into account the potential impact of infections, the experts consider that in daily practice, general risk factors for infection should be regularly assessed when using immunosuppressive drugs.

Statement 15: In patients with axSpA when using NSAIDs, corticosteroids, csDMARDs, b/tsDMARDs, it is recommended to follow the risk management recommendations provided by the summaries of products characteristics and scientific societies (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Risk management in axSpA should be as rigorous as in other diseases such as RA [127]. All available drugs for axSpA patients are associated with the development of adverse events in the short and long term [38].

Regarding vaccination, it has been shown that the rate of seroconversion to the COVID vaccine (95.6%) and to others such as influenza vaccine is optimal in patients with axSpA and immunosuppressive drugs [128,129,130].

Treatment and Treatment Strategy

Statement 16: HLA-B27-positive and -negative axSpA patients respond to b/tsDMARDs. Therefore, in the presence of a robust axSpA diagnosis and active disease, being HLA-B27-negative does not contraindicate the use of b/tsDMARDs (LE 1b; GR A; LA 95%).

Different post hoc and observational studies have depicted that HLA-B27 positivity is independently associated with a better response to TNFi and IL-17i (ASAS40, BASDAI50, ASAS-CRP, or ASDAS-CRP ID) in axSpA patients, at least in the short to medium term [50,51,52, 131]. Data on JAKi are currently scarce. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that HLA-B27-negative patients also respond to available treatments [50,51,52, 131].

Based on these findings, HLA-B27 status could be a (discriminating) factor to take into account when making diagnostic or treatment decisions. For example, in patients with suspected axSpA, refractory to NSAIDs, with normal RCP levels, HLA-B27 negativity might prompt to perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm the diagnosis of axSpA or active disease.

Statement 17: Objective markers of inflammation (CRP and MRI) are associated with better response to b/tsDMARDs. However, the absence of these markers does not indicate a lack of response nor endorse avoiding using b/tsDMARDs (LE 1a; GR A; LA 80%).

An elevated CRP is present in only about 30% of patients with axSpA [132]. Thus, a normal CRP does not rule out axSpA or comprehensively capture active disease. An elevation of CRP predicts future radiographic progression in sacroiliac joints and spine in axSpA patients [45, 53, 55,56,57, 113, 132,133,134]. High CRP levels are also associated with a better response to b/tsDMARDs (ASAS20/40, ASDAS-PCR, etc.) [45, 53, 55,56,57, 113, 132,133,134,135]. Further studies are necessary to analyze the role of CRP levels when using TFC and UPA.

Like CRP, the presence of inflammation on sacroiliac MRI has been associated with increased risk of radiographic progression and a higher likelihood of response to TNFi and IL-17i [52, 57, 58, 112, 113, 136]. More data are needed on JAKi, though preliminary results are in the same line [24].

MRI can help if the diagnosis of axSpA cannot be established based on clinical features and conventional radiography [137, 138]. In addition, MRI can provide evidence of active inflammatory lesions (primarily bone marrow edema) and structural lesions (such as bone erosion, new bone formation, sclerosis, and fat infiltration) that are not clinically detectable [137, 138]. Thus, MRI imaging can help physicians in monitoring and treatment decision-making (start b/tsDMARDs, treatment switches, etc.). However, the experts do not recommend the routine use of MRI as a tool to monitor disease activity or progression. Moreover, experts consider it preferable to have MRI evaluation by an experienced radiologist.

Statement 18: An early treatment strategy adjusted to patients’ characteristics and established therapeutic objectives is recommended (LE 2a; GR B; LA 100%).

Statement 19: More actions and strategies are needed to guarantee an early diagnosis and treatment in axSpA (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Statement 20: Patients with axSpA should be treated regardless of the duration of the disease (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Like in other immune-mediated diseases, early diagnosis and treatment are vital for improving patients' outcomes and prognosis. It should also be borne in mind that axSpA onset usually occurs in young patients who might progress rapidly [139]. However, a SLR reported a pooled mean of diagnostic delay of almost 7 years, and it has been described that up to 50–60% of patients present structural damage at diagnosis [140, 141]. Early disease or the therapeutic window opportunity are not yet defined in axSpA. Some authors support the hypothesis that new bone formation is more likely in advanced inflammatory lesions and proceeds through a process of fat metaplasia, supporting a window of opportunity for disease modification [142]. Further research will address these questions. In the meantime, we consider it important to develop actions and strategies for an early diagnosis and treatment like the implementation of early axSpA units [143], educational activities to improve the knowledge and practical skills of general practitioners (including musculoskeletal and extramusculoskeletal manifestations), or preferential referral algorithms/criteria/protocols. Moreover, taking into account that some patients start the disease with extramusculoskeletal manifestations, close and effective coordination and collaboration with ophthalmologists, dermatologists, or gastroenterologists might contribute positively to the outcome.

Considering the proven efficacy in both the short and long term, as well as the acceptable safety profile of available therapies, it is crucial to make additional efforts to enhance early referral and diagnosis [5, 38].

On the other hand, published evidence has shown that patients with < 5 years of symptom duration respond to TNFi at least as well as patients with > 5 years of symptom duration [144]. Likewise, patients with < 2 years from axSpA symptom onset or those with > 20 years of disease duration respond to treatments equally [29,30,31,32, 145]. Therefore, patients with axSpA should be treated irrespectively of the disease duration.

Adherence

In axSpA, as in other chronic diseases, adherence to medications is suboptimal, especially in the long term [59, 113, 146,147,148].

Different barriers have been identified with non-adherence in axSpA, including age, psychosocial factors, healthcare professional–patient relationship, concerns and perceptions about treatments, depression, lower treatment self-efficacy, and necessity beliefs [149, 150].

Regarding patient preferences, a national survey conducted by a patients organization collected data on 543 with axSpA (86% women, 61% between 48–64 years, 25% on biological therapies) [13]. According to the patients, the level of satisfaction with treatments was low, mean 5.5 (scale 0–10), and it was higher with biological therapies. Oral treatments were preferred to subcutaneous and intravenous [13]. Finally, 43.8% of participants reported that they did not set treatment goals with their doctors [13].

Hence, it is imperative to incorporate individualized attention into the routine care of patients with axSpA to investigate any lack of adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological prescriptions. Tailored interventions to improve adherence can avoid failures or suboptimal responses to treatment.

Discussion

This project has generated overarching principles and recommendations for the management of axSpA patients with a special focus on difficult-to-treat clinical scenarios or controversial areas. They are based on the best evidence currently available and the opinion of an expert panel. Moreover, they were subsequently evaluated by a broad group of rheumatologists.

The Delphi response rate was almost 60%. According to many experts in this study design, a survey response rate of 50% or higher is often considered to be excellent for most circumstances [151]. We also consider it important to point out that a large number of rheumatologists all over the country were invited to participate in order to guarantee the highest representation.

The treatment options for axSpA have substantially expanded over the last decade with proven efficacy in the short and long term and an acceptable safety profile [5, 38]. Despite current therapeutic armamentarium and T2T strategy for axSpA patients, there is still a great variability in the clinical practice [4,5,6]. As a consequence, in recent years, national and international societies have published recommendations for the management of these patients. However, these documents do not entirely cover all clinical scenarios for which clinicians still seek guidance. In order to fill this gap, we performed this project to generate specific and practical recommendations [7,8,9].

One of our main conclusions is that given the heterogeneity of axSpA, physicians should carefully evaluate the impact of individual manifestations and comorbidities on patients (disability, family and social relationships, quality of life, etc.). Along with the evaluation of clinical objective data and prognostic factors, patients’ perspectives might help prioritize treatment and treatment strategy in a shared decision-making approach. We would also like to highlight that integrating imaging and clinical assessment with biomarker analysis could also help provide personalized medicine in axSpA. Further studies are necessary to clarify this question.

On the other hand, it is important to mention that in daily practice, although pain is a pivotal complaint in several axSpA domains, other causes of pain or conditions (e.g., mechanical pain, depression, central sensitization) should be ruled out, especially in patients with multiple painful enthesis. These painful syndromes, led by fibromyalgia, are quite frequent in axSpA and might lead to a false diagnosis of therapeutic failure or even overtreatment.

Regarding the treatment selection and stratification, we have provided a guide in several subgroups of patients or clinical scenarios that might generate clinical uncertainty. For example, in axSpA patients with refractory enthesitis, b/tsDMARDs were recommended, or in certain EMMs like uveitis or IBD, specific therapies (TNFi or JAKi) were preferred. Along with these recommendations, we also stated that the presence of significant structural damage, long disease duration, or HLA-B27-negative status do not contraindicate the use of b/tsDMARDs.

Comorbidities add a significant burden to axSpA by contributing to disease activity, functional and work disability, and even mortality [86], but they can also have an impact on treatment decisions. For example, although NSAIDs have demonstrated efficacy in axSpA [41, 98], NSAIDs should be prescribed with caution, especially for patients with documented CVD or in the presence of CVD risk factors.

Finally, when using NSAIDs, corticosteroids, csDMARDs, b/tsDMARDs, we have recommended following the risk management recommendations provided by the summaries of products characteristics and scientific societies [7, 9].

It is worth mentioning the lack of current definition of difficult-to treat or refractory axSpA. Several authors have proposed an extrapolated definition (of rheumatoid arthritis) of difficult-to treat or refractory axSpA [152]. However, more research is needed to properly establish a definition.

The primary limitation of this study is the absence of published high-quality evidence that specifically addresses certain issues. Expert opinion is probably the most appropriate way to bring recommendations to resolve uncertainty. In this regard, a strength of the study is the broad evaluation of the statements that was extended to a significant number of rheumatologists through a Delphi process. A very high level of agreement in all of them was reached, which increases the validity of the recommendations.

Conclusions

Treatment decisions are not always straightforward in axSpA. We have proposed overarching principles and recommendations for the management of axSpA patients regarding difficult-to-treat clinical scenarios or controversial areas, based on the best evidence available and the opinion of an expert panel. We are confident that these recommendations will find their way into the clinic for better care of axSpA patients in a real-world setting.

References

Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, El-Zorkany B, van der Heijde D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(12):1511–21.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):777–83.

López-Medina C, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Dougados M, Molto A. Characteristics and burden of disease in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a comparison by systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2019;5(2): e001108.

Webers C, Ortolan A, Sepriano A, Falzon L, Baraliakos X, Landewé RBM, et al. Efficacy and safety of biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):130–41.

Ortolan A, Webers C, Sepriano A, Falzon L, Baraliakos X, Landewé RB, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological and non-biological interventions: a systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):142–52.

Molto A, López-Medina C, Van den Bosch F, Boonen A, Webers C, Dernis E, et al. Efficacy of a tight-control and treat-to-target strategy in axial spondyloarthritis: results of the open-label, pragmatic, cluster-randomised TICOSPA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(11):1436–44.

Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, Ortolan A, Webers C, Baraliakos X, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):19–34.

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Dubreuil M, Yu D, Khan MA, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1599–613.

Gratacós J, Del Campo D, Fontecha P, Fernández-Carballido C, JuanolaRoura X, Linares Ferrando LF, de Miguel ME, et al. Recommendations by the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on the Use of Biological Therapies in Axial Spondyloarthritis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2018;14(6):320–33.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358: j4008.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Loza E, Plazuelo P. Patients with spondyloarthritis including psoriatic arthritis: current needs, impact and perspectives. Reumatol Clin. 2023;19(5):273–8.

(CEBM) OUCfE-BM. CEBM Levels of Evidence 2011 2011 [Available from: https://www.cebm.net/.

Chen J, Liu C. Methotrexate for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:4524.

Dhir V, Mishra D, Samanta J. Glucocorticoids in spondyloarthritis-systematic review and real-world analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(10):4463–75.

Chen J, Lin S, Liu C. Sulfasalazine for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:4800.

Li S, Li F, Mao N, Wang J, Xie X. Efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;102:47–53.

Corbett M, Soares M, Jhuti G, Rice S, Spackman E, Sideris E, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(9):1–334.

Schett G, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Deodhar A, Østergaard M, Gupta AD, et al. Secukinumab efficacy on enthesitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: pooled analysis of four pivotal phase III studies. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(8):1251–8.

van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, Mease P, Deodhar A, Maksymowych WP, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16-week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392(10163):2441–51.

Deodhar A, Van den Bosch F, Poddubnyy D, Maksymowych WP, van der Heijde D, Kim TH, et al. Upadacitinib for the treatment of active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10349):369–79.

Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, Fleishaker D, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(8):1004–13.

van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, Deodhar A, van den Bosch F, Maksymowych WP, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394(10214):2108–17.

Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Van den Bosch F, Maksymowych WP, Kim T-H, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and an inadequate response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy: one-year results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study and open-label extension. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(1):70–80.

Vander Cruyssen B, Vastesaeger N, Collantes-Estévez E. Hip disease in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(4):448–54.

Fendler C, Baraliakos X, Braun J. Glucocorticoid treatment in spondyloarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(5 Suppl 68):S139–42.

Vander Cruyssen B, Muñoz-Gomariz E, Font P, Mulero J, de Vlam K, Boonen A, et al. Hip involvement in ankylosing spondylitis: epidemiology and risk factors associated with hip replacement surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(1):73–81.

Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Burmester G, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: an open, observational, extension study of a three-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(8):2224–33.

Ajrawat P, Touma Z, Sari I, Taheri C, Diaz Martinez JP, Haroon N. Effect of TNF-inhibitor therapy on spinal structural progression in ankylosing spondylitis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(6):728–43.

van der Heijde D, Pangan AL, Schiff MH, Braun J, Borofsky M, Torre J, et al. Adalimumab effectively reduces the signs and symptoms of active ankylosing spondylitis in patients with total spinal ankylosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(9):1218–21.

Shim MR. Efficacy of TNF inhibitors in advanced ankylosing spondylitis with total spinal fusion: case report and review of literature. Open Access Rheumatol. 2019;11:173–7.

Roche D, Badard M, Boyer L, Lafforgue P, Pham T. Incidence of anterior uveitis in patients with axial spondyloarthritis treated with anti-TNF or anti-IL17A: a systematic review, a pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):192.

Marzo-Ortega H, Sieper J, Kivitz AJ, Blanco R, Cohen M, Pavelka K, et al. 5-year efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: end-of-study results from the phase 3 MEASURE 2 trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(6):e339–46.

Deodhar A, Baeten D, Sieper J, Porter B, Richards H, Widmer A. Safety and tolerability of secukinumab in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: pooled safety analysis of two international phase 3, randomized, controlled trials. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22(3):139–40.

Gómez-Gómez A, Loza E, Rosario MP, Espinosa G, Morales J, Herreras JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of immunomodulatory drugs in patients with anterior uveitis: a systematic literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(42): e8045.

Wu D, Guo Y-Y, Xu N-N, Zhao S, Hou L-X, Jiao T, et al. Efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):19.

Webers C, Ortolan A, Sepriano A, Falzon L, Baraliakos X, Landewé RBM, et al. Efficacy and safety of biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):130–41.

Liew JW, Huang IJ, Louden DN, Singh N, Gensler LS. Association of body mass index on disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2020;6:1.

Zurita Prada PA, UrregoLaurín CL, GuillénAstete CA, KanaffoCaltelblanco S, Navarro-Compán V. Influence of smoking and obesity on treatment response in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(5):1673–86.

Regel A, Sepriano A, Baraliakos X, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological and non-biological pharmacological treatment: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017;3:1.

Hameed RH. Risk of myocardial infarction in spondyloarthritis and osteoarthritis patients using NSAIDS. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2019;13(4):1238–43.

Karmacharya P, Duarte-Garcia A, Dubreuil M, Murad MH, Shahukhal R, Shrestha P, et al. Effect of therapy on radiographic progression in axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(5):733–49.

Kivitz AJ, Marzo-Ortega H, Legerton C, Sieper J, Blanco R, Cohen M, et al. High retention rate and sustained responses with secukinumab 150mg in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 3-year results from a phase 3 study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69 (supp 10):2.

Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Gensler LS, Kim T-H, Maksymowych WP, Østergaard M, et al. Ixekizumab for patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-X): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10217):53–64.

Briot K, Etcheto A, Miceli-Richard C, Dougados M, Roux C. Bone loss in patients with early inflammatory back pain suggestive of spondyloarthritis: results from the prospective DESIR cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(2):335–42.

Prieto-Alhambra D, Muñoz-Ortego J, De Vries F, Vosse D, Arden NK, Bowness P, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis confers substantially increased risk of clinical spine fractures: a nationwide case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(1):85–91.

Ashany D, Stein EM, Goto R, Goodman SM. The effect of TNF inhibition on bone density and fracture risk and of IL17 inhibition on radiographic progression and bone density in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic literature review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21(5):20.

Fitzgerald GE, O’Dwyer T, Mockler D, O’Shea FD, Wilson F. Pharmacological treatment for managing bone health in axial spondyloarthropathy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(9):1369–84.

Maksymowych WP, Kumke T, Auteri SE, Hoepken B, Bauer L, Rudwaleit M. Predictors of long-term clinical response in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis receiving certolizumab pegol. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):274.

Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Lenaerts J, Wollenhaupt J, Myasoutova L, Park S-H, et al. Partial remission in ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in treatment with infliximab plus naproxen or naproxen alone: associations between partial remission and baseline disease characteristics. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):1946–53.

Braun J, Blanco R, Marzo-Ortega H, Gensler LS, van den Bosch F, Hall S, et al. Secukinumab in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: subgroup analysis based on key baseline characteristics from a randomized phase III study, PREVENT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):231.

Zhang J-R, Pang D-D, Dai S-M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are unlikely to inhibit radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:214.

Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, Baeten D, Sieper J, Emery P, et al. Effect of secukinumab on clinical and radiographic outcomes in ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results from the randomised phase III MEASURE 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1070–7.

Braun J, Deodhar A, Landewe R, Baraliakos X, Miceli-Richard C, Sieper J, et al. Impact of baseline C-reactive protein levels on the response to secukinumab in ankylosing spondylitis: 3-year pooled data from two phase III studies. RMD Open. 2018;4:2.

Deodhar A, Conaghan PG, Kvien TK, Strand V, Sherif B, Porter B, et al. Secukinumab provides rapid and persistent relief in pain and fatigue symptoms in patients with ankylosing spondylitis irrespective of baseline C-reactive protein levels or prior tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapy: 2-year data from the MEASURE 2 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(2):260–9.

Maksymowych WP, Bolce R, Gallo G, Seem E, Geneus VJ, Sandoval DM, et al. Ixekizumab in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis with and without elevated C-reactive protein or positive magnetic resonance imaging. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(11):4324–34.

Huang Y, Chen Y, Liu T, Lin S, Yin G, Xie Q. Impact of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors on MRI inflammation in axial spondyloarthritis assessed by Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium Canada score: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12): e0244788.

Yu C-L, Yang C-H, Chi C-C. Drug survival of biologics in treating ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. BioDrugs. 2020;34(5):669–79.

Joo W, Almario CV, Ishimori M, Park Y, Jusufagic A, Noah B, et al. Examining treatment decision-making among patients with axial spondyloarthritis: insights from a conjoint analysis survey. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(7):391–400.

van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, Sieper J, Van den Bosch F, Listing J, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1811–8.

Navarro-Compán V, Boel A, Boonen A, Mease P, Landewé R, Kiltz U, et al. The ASAS-OMERACT core domain set for axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(6):1342–9.

Molina Collada J, Trives L, Castrejón I. The importance of outcome measures in the management of inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Open Access Rheumatol. 2021;13:191–200.

de Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Baeten DL. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):196.

McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, Marzo-Ortega H, Eder L, Ciurtin C. Hidden in plain sight: Is there a crucial role for enthesitis assessment in the treatment and monitoring of axial spondyloarthritis? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(6):1147–61.

Mease PJ. Fibromyalgia, a missed comorbidity in spondyloarthritis: prevalence and impact on assessment and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29(4):304–10.

López-Medina C, Moltó A. Comorbid pain in axial spondyloarthritis, including fibromyalgia. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:175.

López-Medina C, Castro-Villegas MC, Collantes-Estévez E. Hip and shoulder involvement and their management in axial spondyloarthritis: a current review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22(9):53.

Lian F, Yang X, Liang L, Xu H, Zhan Z, Qiu Q, et al. Treatment efficacy of etanercept and MTX combination therapy for ankylosing spondylitis hip joint lesion in Chinese population. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(6):1663–7.

Konsta M, Sfikakis PP, Bournia VK, Karras D, Iliopoulos A. Absence of radiographic progression of hip arthritis during infliximab treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(8):1229–32.

Song R, Chung SW, Lee SH. Radiographic evidence of hip joint recovery in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents: a case series. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(11):1759–60.

Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Emery P, Delicha EM, et al. Secukinumab shows sustained efficacy and low structural progression in ankylosing spondylitis: 4-year results from the MEASURE 1 study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(5):859–68.

Espinosa G, Muñoz-Fernández S, García Ruiz JM, Herreras JM, Cordero-Coma M. Treatment recommendations for non-infectious anterior uveitis. Med Clin. 2017;149(12):552.

Dick AD, Rosenbaum JT, Al-Dhibi HA, Belfort R Jr, Brézin AP, Chee SP, et al. Guidance on noncorticosteroid systemic immunomodulatory therapy in noninfectious Uveitis: fundamentals of care for UveitiS (FOCUS) initiative. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(5):757–73.

Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Boonen A. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):65–73.

Macfarlane GJ, Biallas R, Dean LE, Jones GT, Goodson NJ, Rotariu O. Inflammatory bowel disease risk in patients with axial spondyloarthritis treated with biologic agents determined using the BSRBR-AS and a metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2023;50(2):175–84.

Barberio B, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in induction and maintenance of remission in luminal Crohn’s disease: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2023;72(2):264–74.

Burr NE, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326390.

Akobeng AK, Zachos M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2003(1):3574.

Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61(12):1693–700.

Li Y, Yao C, Xiong Q, Xie F, Luo L, Li T, et al. Network meta-analysis on efficacy and safety of different Janus kinase inhibitors for ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(7):851–9.

Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, Pangan AL, Siffledeen J, Greenbloom S, et al. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2113–28.

Moltó A, Etcheto A, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, van den Bosch F, Bautista Molano W, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and evaluation of their screening in spondyloarthritis: results of the international cross-sectional ASAS-COMOSPA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1016–23.

Zhao SS, Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ, Hughes DM, Moots RJ, Goodson NJ. Comorbidity and response to TNF inhibitors in axial spondyloarthritis: longitudinal analysis of the BSRBR-AS. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(9):4158–65.

Zhao SS, Jones GT, Hughes DM, Moots RJ, Goodson NJ. Depression and anxiety symptoms at TNF inhibitor initiation are associated with impaired treatment response in axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(12):5734–42.

Moltó A, Nikiphorou E. Comorbidities in spondyloarthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:62.

Drosos GC, Vedder D, Houben E, Boekel L, Atzeni F, Badreh S, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(6):768–79.

Kerola AM, Kazemi A, Rollefstad S, Lillegraven S, Sexton J, Wibetoe G, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: a nationwide registry study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(12):4656–66.

Exarchou S, Lie E, Lindström U, Askling J, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Turesson C, et al. Mortality in ankylosing spondylitis: results from a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(8):1466–72.

Prati C, Claudepierre P, Pham T, Wendling D. Mortality in spondylarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78(5):466–70.

Glintborg B, Højgaard P, Lund Hetland M, Steen Krogh N, Kollerup G, Jensen J, et al. Impact of tobacco smoking on response to tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(4):659–68.

Chung HY, Machado P, van der Heijde D, D’Agostino MA, Dougados M. Smokers in early axial spondyloarthritis have earlier disease onset, more disease activity, inflammation and damage, and poorer function and health-related quality of life: results from the DESIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):809–16.

Micheroli R, Hebeisen M, Wildi LM, Exer P, Tamborrini G, Bernhard J, et al. Impact of obesity on the response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):164.

Kiltz U, Brandt-Juergens J, Kästner P, Riechers E, Peterlik D, Budden C, et al. AB0751 How does body mass index affect secukinumab treatment outcomes and safety in patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Real-world data from the German AQUILA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(Suppl 1):1500–1.

Alonso S, Villa I, Fernández S, Martín JL, Charca L, Pino M, et al. Multicenter study of secukinumab survival and safety in spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: SEcukinumab in Cantabria and ASTURias Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8: 679009.

Norton H, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Hala T, Elzorkany B, Stockert L, Sh H, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis by baseline BMI: a post hoc analysis of phase 2 and phase 3 trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2022;74(suppl 9).

Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):17–28.

Torgutalp M, Rios Rodriguez V, Dilbaryan A, Proft F, Protopopov M, Verba M, et al. OP0021 Treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is associated with retardation of radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: 10-year results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(Suppl 1):14–5.

Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, Koch GG, Fleischmann R, Rivas JL, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316–26.

Zhao SS, Robertson S, Reich T, Harrison NL, Moots RJ, Goodson NJ. Prevalence and impact of comorbidities in axial spondyloarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(4):47–57.

Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87(3):235–41.

de Olry Labry Lima A, Salamanca-Fernández E, Alegre Del Rey EJ, Matas Hoces A, González Vera M, Bermúdez Tamayo C. Safety considerations during prescription of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), through a review of systematic reviews. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2021;44(2):261–73.

Kotyla PJ. Bimodal function of anti-TNF treatment: shall we be concerned about anti-TNF treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and heart failure? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:6.

Hansen KE, Mortezavi M, Nagy E, Wang C, Connell CA, Radi Z, et al. Fracture in clinical studies of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022;14:1759.

Ortolan A, Lorenzin M, Tadiotto G, Russo FP, Oliviero F, Felicetti M, et al. Metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver stiffness in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(10):2843–50.

Carrascosa JM, Vilarrasa E, Belinchón I, Herranz P, Crespo J, Guimerá F, et al. [Translated article] Common approach to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease in patients with psoriasis: consensus-based recommendations from a multidisciplinary group of experts. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023;114(5):T392-t401.

Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Balanescu A, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Boonen A, Cavalli G, et al. 2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):48–56.

Fouque-Aubert A, Jette-Paulin L, Combescure C, Basch A, Tebib J, Gossec L. Serious infections in patients with ankylosing spondylitis with and without TNF blockers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1756–61.

Hou L-Q, Jiang G-X, Chen Y-F, Yang X-M, Meng L, Xue M, et al. The comparative safety of TNF inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis-a meta-analysis update of 14 randomized controlled trials. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(2):234–43.

Ma Z, Liu X, Xu X, Jiang J, Zhou J, Wang J, et al. Safety of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(25): e7145.

Man S, Hu L, Ji X, Wang Y, Ma Y, Wang L, et al. Risk of malignancy and tuberculosis of biological and targeted drug in patients with spondyloarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12: 705669.

Maxwell LJ, Zochling J, Boonen A, Singh JA, Veras MMS, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:5468.

Sepriano A, Regel A, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, Baraliakos X, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of biological and targeted-synthetic DMARDs: A systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017;3:1.

Sun WT, He YH, Dong MM, Zhang YN, Peng KX, Zhang YM, et al. The comparative safety of biological treatment in patients with axial spondylarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with placebo. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(19):9824–36.

Wang P, Zhang S, Hu B, Liu W, Lv X, Chen S, et al. Efficacy and safety of interleukin-17A inhibitors in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(8):3053–65.

Wang Q, Wen Z, Cao Q. Risk of tuberculosis during infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and spondyloarthropathy: a meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(3):1693–704.

Wang S, He Q, Shuai Z. Risk of serious infections in biological treatment of patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(2):439–50.

Xu Z, Xu P, Fan W, Yang G, Wang J, Cheng Q, et al. Risk of infection in patients with spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis receiving antitumor necrosis factor therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(4):3491–500.

Cecconi M, Ranza R, Titton DC, Moraes JCB, Bertolo M, Bianchi W, et al. Incidence of infectious adverse events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis on biologic drugs-data from the Brazilian registry for biologics monitoring. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26(2):73–8.

Wallis D, Thavaneswaran A, Haroon N, Ayearst R, Inman RD. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and infection risk in axial spondyloarthritis: results from a longitudinal observational cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(1):152–6.

Kim HW, Park JK, Yang JA, Yoon YI, Lee EY, Song YW, et al. Comparison of tuberculosis incidence in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis during tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment in an intermediate burden area. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(9):1307–12.

Kim EM, Uhm WS, Bae SC, Yoo DH, Kim TH. Incidence of tuberculosis among Korean patients with ankylosing spondylitis who are taking tumor necrosis factor blockers. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(10):2218–23.

Fragoulis GE, Nikiphorou E, Dey M, Zhao SS, Courvoisier DS, Arnaud L, et al. 2022 EULAR recommendations for screening and prophylaxis of chronic and opportunistic infections in adults with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(6):742–53.

Dougados M, Wei JCC, Landewé R, Sieper J, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(2):176–85.

Baraliakos X, Kivitz AJ, Deodhar AA, Braun J, Wei JC, Delicha EM, et al. Long-term effects of interleukin-17A inhibition with secukinumab in active ankylosing spondylitis: 3-year efficacy and safety results from an extension of the Phase 3 MEASURE 1 trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(1):50–5.

Moreno-Ramos MJ, Sanchez-Piedra C, Martínez-González O, Rodríguez-Lozano C, Pérez-Garcia C, Freire M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and treatment retention of secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: a descriptive observational analysis of the Spanish BIOBADASER registry. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(4):1031–47.

Gómez Reino J, Loza E, Andreu JL, Balsa A, Batlle E, Cañete JD, et al. Consensus statement of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on risk management of biologic therapy in rheumatic patients. Reumatol Clin. 2011;7(5):284–98.

Jena A, Mishra S, Deepak P, Kumar-M P, Sharma A, Patel YI, et al. Response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in immune mediated inflammatory diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21(1): 102927.

Andreica I, Blazquez-Navarro A, Sokolar J, Anft M, Kiltz U, Pfaender S, et al. Different humoral but similar cellular responses of patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases under disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs after COVID-19 vaccination. RMD Open. 2022;8:2.

Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, Agmon-Levin N, van Assen S, Bijl M, et al. 2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):39–52.

Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, Mohamoud AA, Krogh NS, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis versus nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: comparison of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor effectiveness and effect of HLA-B27 status. An observational cohort study from the nationwide DANBIO registry. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(1):59–69.

Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, Listing J, Märker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):717–27.

Braun J, Baraliakos X, Hermann K-GA, Xu S, Hsu B. Serum C-reactive protein levels demonstrate predictive value for radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with golimumab. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1704–12.

Bredella MA, Steinbach LS, Morgan S, Ward M, Davis JC. MRI of the sacroiliac joints in patients with moderate to severe ankylosing spondylitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(6):1420–6.

Maksymowych W, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Ganz F, Gao T, et al. Efficacy of Upadacitinib in Patients with Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis Stratified by Objective Signs of Inflammation at Baseline [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2022;74(suppl 9).

Khoury G, Combe B, Morel J, Lukas C. Change in MRI in patients with spondyloarthritis treated with anti-TNF agents: systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(2):242–52.

Mandl P, Navarro-Compán V, Terslev L, Aegerter P, van der Heijde D, D’Agostino MA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(7):1327–39.

Baraliakos X, Østergaard M, Lambert RG, Eshed I, Machado PM, Pedersen SJ, et al. MRI lesions of the spine in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: an update of lesion definitions and validation by the ASAS MRI working group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1243–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222081

Wang R, Ward MM. Epidemiology of axial spondyloarthritis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):137–43.