Abstract

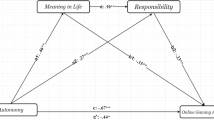

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationships between the self-efficacies and the attitudes toward Web-based Recipe Learning (WRL) of 296 culinary college students in Taiwan. Factors of the WRL Self-Efficacy Scale and the WRL Attitudes Scale were identified in this study using exploratory factor analyses. Both scales showed a good inter-correlation matrix. Correlation and mediational effect analyses were used to examine the relationships between the students’ self-efficacy and attitudes, and several significant findings are reported. First, students’ self-efficacies had positive relations with their attitudes toward WRL. In addition, students’ ‘Ingredient Recognition’ self-efficacy was found to significantly predict the other two dimensions of self-efficacy: ‘Knife Skills’ and ‘Cooking Procedure.’ Moreover, students’ ‘Ingredient Recognition’ self-efficacy was found to significantly predict their WRL attitudes of ‘Usefulness’ via a mediated variable, ‘Cooking Procedure’ self-efficacy. To sum up, the results suggest that ‘Ingredient Recognition’ is a fundamental level of WRL self-efficacy, while both ‘Knife Skills’ and ‘Cooking Procedure’ are advanced levels of WRL self-efficacies. And, when considering the mediational effect, culinary college students’ self-efficacy for cooking procedure is an important mediator between the fundamental self-efficacy and attitudes in web-based culinary learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ali, A., Murphy, H. C., & Nadkarni, S. (2014). Hospitality students’ perceptions of digital tools for learning and sustainable development. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 15, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2014.02.001.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1996). Multifaced impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67, 1206–1222.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Adolescence and education (Vol. 5, pp. 307–337)., Self-efficacy and adolescence Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Brumini, G., Spalj, S., Mavrinac, M., Biocina-Lukenda, D., Strujic, M., & Brumini, M. (2014). Attitudes towards e-learning amongst dental students at the universities in Croatia. European Journal of Dental Education, 18(1), 15–23. doi:10.1111/eje.12068.

Chan, Y. H. (2003). Biostatistics 101: Data presentation. Singapore Medical Journal, 44(6), 280–285.

Chang, C. S., Liu, E. Z. F., Sung, H. Y., Lin, C. H., Chen, N. S., & Cheng, S. S. (2014). Effects of online college student’s Internet self-efficacy on learning motivation and performance. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(4), 366–377. doi:10.1080/14703297.2013.771429.

Cheng, S. Y. (2013). An empirical investigation of the effectiveness of project-based course learning within hospitality programs: The mediating role of cognitive engagement. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 213–225. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2013.10.002.

Chiu, Y. L., & Tsai, C. C. (2014). The roles of social factor and internet self-efficacy in nurses’ web-based continuing learning. Nurse Education Today, 34(3), 446–450. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.013.

Chu, R. J., & Chu, A. Z. (2010). Multi-level analysis of peer support, Internet self-efficacy and e-learning outcomes—the contextual effects of collectivism and group potency. Computers & Education, 55(1), 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.12.011.

Chuang, S. C., Lin, F. M., & Tsai, C. C. (2015). An exploration of the relationship between Internet self-efficacy and sources of internet self-efficacy among Taiwanese university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 147–155. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.044.

Condrasky, M. D., Williams, J. E., Catalano, P. M., & Griffin, S. F. (2011). Development of psychosocial scales for evaluating the impact of a culinary nutrition education program on cooking and healthful eating. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 43(6), 511–516. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.013.

Cunningham-Sabo, L., & Lohse, B. (2014). Impact of a school-based cooking curriculum for fourth-grade students on attitudes and behaviors is influenced by gender and prior cooking experience. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46(2), 110–120. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.09.007.

De Backer, C. J. S., & Hudders, L. (2016). Look who’s cooking. Investigating the relationship between watching educational and edutainment TV cooking shows, eating habits and everyday cooking practices among men and women in Belgium. Appetite, 96, 494–501. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.10.016.

Heusdens, W. T., Bakker, A., Baartman, L. K. J., & De Bruijn, E. (2016). Contextualising vocational knowledge: A theoretical framework and illustrations from culinary education. Vocations and Learning, 9(1), 1–15. doi:10.1007/s12186-015-9145-0.

Hsu, L. W. (2015). Modelling determinants for the integration of Web 2.0 technologies into hospitality education: A Taiwanese case. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(4), 625–633. doi:10.1007/s40299-014-0208-z.

Jonasson, C. (2015). Interactional processes of handling errors in vocational school: Students attending to changes in vocational practices. Vocations and Learning, 8(1), 75–93. doi:10.1007/s12186-014-9124-x.

Kao, C. P., & Tsai, C. C. (2009). Teachers’ attitudes toward web-based professional development, with relation to Internet self-efficacy and beliefs about web-based learning. Computers & Education, 53(1), 66–73. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.019.

Kapucu, S., & Bahcivan, E. (2015). High school students’ scientific epistemological beliefs, self-efficacy in learning physics and attitudes toward physics: A structural equation model. Research in Science & Technological Education, 33(2), 252–267. doi:10.1080/02635143.2015.1039976.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24, 163–204.

Ko, W. H. (2012). A study of the relationships among effective learning, professional competence, and learning performance in culinary field. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 11(1), 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2012.02.010.

Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E. E., & Belland, B. R. (2014). Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet and Higher Education, 20, 35–50. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.001.

Liang, J. C., Wu, S. H., & Tsai, C. C. (2011). Nurses’ Internet self-efficacy and attitudes toward web-based continuing learning. Nurse Education Today, 31(8), 768–773. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.11.021.

Liburd, J. J., & Christensen, I. M. F. (2013). Using web 2.0 in higher tourism education. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 12(1), 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2012.09.002.

Mejia, C., & Phelan, K. V. (2013). Normative factors influencing hospitality instructors to teach online. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 168–179. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2013.09.005.

Mulligan, A., & Mabe, M. (2011). The effect of the internet on researcher motivations, behaviour and attitudes. Journal of Documentation, 67(2), 290–311. doi:10.1108/00220411111109485.

Peng, H. Y., Tsai, C. C., & Wu, Y. T. (2006). University students’ self-efficacy and their attitudes toward the internet: the role of students’ perceptions of the internet. Educational Studies, 32(1), 73–86. doi:10.1080/03055690500416025.

Schwarz, N., & Bohner, G. (2001). The construction of attitudes. In A. Tesser & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes (Vol. 1, pp. 436–457). Oxford: Blackwell.

Shen, D. M., Cho, M. H., Tsai, C. L., & Marra, R. (2013). Unpacking online learning experiences: Online learning self-efficacy and learning satisfaction. Internet and Higher Education, 19, 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.04.001.

Sigala, M. (2012). Investigating the role and impact of geovisualisation and geocollaborative portals on collaborative e-learning in tourism education. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 11(1), 50–66. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2012.02.001.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x.

Sung, S. C., Huang, H. C., & Lin, M. H. (2015). Relationship between the knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy on sexual health care for nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(3), 254–261. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.11.001.

Teng, C. C. (2013). Developing and evaluating a hospitality skill module for enhancing performance of undergraduate hospitality students. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 78–86. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2013.07.003.

Tsai, C. C., Chuang, S. C., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, M. J. (2011). Self-efficacy in internet-based learning environments: A literature review. Educational Technology & Society, 14(4), 222–240.

Tsai, C.-C., Lin, S. S. J., & Tsai, M.-J. (2001). Developing an internet attitude scale for high school students. Computers & Education, 37, 41–51. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(01)00033-1.

Tsai, M. J., & Tsai, C. C. (2003). Information searching strategies in Web-based science learning: The role of Internet self-efficacy. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 40(1), 43–50. doi:10.1080/135500032000038822.

Tsai, M. J., & Tsai, C. C. (2010). Junior high school students’ Internet usage and self-efficacy: A re-examination of the gender gap. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1182–1192. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.004.

Tsai, P. S., Tsai, C. C., & Hwang, G. H. (2010). Elementary school students’ attitudes and self-efficacy of using PDAs in a ubiquitous learning context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 297–308.

Tsai, M. J., Hsu, C. Y., & Tsai, C. C. (2012). Investigation of high school students’ online science information searching performance: The role of implicit and explicit strategies. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 21(2), 246–254. doi:10.1007/s10956-011-9307-2.

Uitto, A. (2014). Interest, attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs explaining upper-secondary school students’ orientation towards biology-related careers. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 12(6), 1425–1444. doi:10.1007/s10763-014-9516-2.

Wang, C.-Y., Tsai, M.-J., & Tsai, C.-C. (2016). Multimedia recipe reading: Predicting learning outcomes and diagnosing cooking interest using eye-tracking measures. Computers in Human Behavior, 62(3), 9–18.

Wang, Y.-L., Tsai, C.-C., & Wei, S.-H. (2015). The sources of science teaching self-efficacy among elementary school teachers: A mediational model approach. International Journal of Science Education, 37, 2264–2283. doi:10.1080/09500693.2015.1075077.

Worsley, A., Wang, W., Ismail, S., & Ridley, S. (2014). Consumers’ interest in learning about cooking: the influence of age, gender and education. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(3), 258–264. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12089.

Wu, Y. T., & Tsai, C. C. (2006). University students’ Internet attitudes and Internet self-efficacy: A study at three universities in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(4), 441–450. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.441.

Yeh, I. J., Kao, C. P., Huang, C. H., & Chang, K. W. (2013). Exploring adult learners’ preferences toward online learning environments: The role of internet self-efficacy and attitudes. Anthropologist, 16(3), 487–494.

Acknowledgement

This paper was financially supported by the research projects provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan under the following grant numbers: MOST 103-2511-S-011-005-MY3 and MOST 103-2511-S-011-002-MY3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Web-based Recipe Learning Self-Efficacy Scale

Ingredient Recognition (IR)

-

IR1. I believe that I can recognize the ingredients in the web-based recipe.

-

IR2. I believe that I can recognize the category of ingredients based on the web-based recipe (e.g., vegetables or meat).

-

IR3. I believe that I can understand the features of each ingredient in the web-based recipe.

-

IR4. I feel that it is very easy to recognize the ingredients in the web-based recipe.

Knife Skills (KS)

-

KS1. I believe that I can cut the ingredients into the shape I want in accordance with the web-based recipe.

-

KS2. I believe that I can cut the ingredients into the shape that matches the web-based recipe.

-

KS3. I believe that I can execute the knife skills in accordance with the web-based recipe.

-

KS4. I believe that I cannot cut the ingredients into the same shape as shown in the web-based recipe.*

-

KS5. For me, it is very easy to cut the ingredients into the same shape as shown in the web-based recipe.

-

KS6. I feel that it is very difficult to perform similar knife skills in accordance with the web-based recipe.*

Cooking Procedure (CP)

-

CP1. I believe that I can remember the whole cooking procedure in the web-based recipe.

-

CP2. I believe that I can remember the cooking order in the web-based recipe.

-

CP3. For me, it is easy to memorize the cooking procedures in the web-based recipe.

-

CP4. I believe that I can understand the reason for each step in the cooking procedure in the web-based recipe.

*Scored in reverse

Appendix 2: Web-based Recipe Learning Attitudes Scale

Easiness (E)

-

E1. It is easy to learn to cook through web-based recipes.

-

E2. Web-based recipes make it easier for me to learn to cook.

-

E3. Web-based recipes allow me to finish my tasks in a shorter time.

-

E4. Web-based recipe contents are clear and concise, and thus are easy for me to learn.

-

E5. Web-based recipes are flexible, and thus are easy for me to learn.

-

E6. Web-based recipes have diverse teaching, and thus are easy for me to learn.

Usefulness (U)

-

U1. It is more interesting to learn about cooking processes through web-based recipes.

-

U2. Web-based recipes allow me to think of more imaginative cooking processes.

-

U3. Web-based recipes effectively enhance my cooking proficiency.

-

U4. Web-based recipes bring about good learning outcomes.

-

U5. It is more efficient to learn to cook through web-based recipes.

-

U6. Web-based recipes increase my learning ability.

-

U7. Using web-based recipes is a useful way to learn.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, CY., Tsai, MJ. Students’ Self-Efficacy and Attitudes Toward Web-Based Recipe Learning in Taiwan Culinary Education. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 26, 193–204 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0340-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0340-7