Abstract

Background

Critically ill neonates and paediatric patients may be at a greater risk of medication-related safety incidents than those in other clinical areas.

Objective

This study aimed to examine the nature of, and contributory factors associated with, medication-related safety incidents reported in neonatal and paediatric intensive care units (ICUs).

Methods

We carried out a mixed-methods analysis of anonymised medication safety incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning System that involved children (aged ≤ 18 years) admitted to ICUs across England and Wales over a 9-year period (2010–2018). Data were analysed descriptively, and free-text descriptions of harmful incidents were examined to explore potential contributory factors associated with incidents.

Results

In total, 25,567 eligible medication-related incident reports were examined. Incidents commonly occurred during the medicines administration (n = 13,668 [53.5%]) and prescribing stages (n = 7412 [29%]). The most commonly implicated error types were drug omission (n = 4812 [18.8%]) and dosing errors (n = 4475 [17.5%]). Neonates were commonly involved in reported incidents (n = 12,235 [47.9%]). Anti-infectives (n = 6483 [25.4%]) were the medications most commonly associated with incidents and commonly involved neonates. Incidents that were reported to have caused patient harm accounted for 12.2% (n = 3129) and commonly involved neonates (n = 1570/3129 [50.2%]). Common contributing factors to harmful incidents included staff-related factors (68.7%), such as failure to follow protocols or errors in documentation, which were often associated with working conditions, inadequate guidelines, and design of systems and protocols.

Conclusions

Neonates were commonly involved in medication-related incidents reported in children’s intensive care settings. Improvements in staffing and workload, design of systems and processes, and the use of anti-infective medications may reduce this risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

An understanding of the type of, and factors contributing to, medication safety incidents in neonatal and children’s intensive care settings is essential to inform the planning of interventions to improve medication safety. |

Incidents involving medication administration and prescribing stages, medication omissions, wrong doses, and anti-infective medications were most commonly reported. Incidents involving neonates were most frequently reported, and most harmful incidents involved this patient population. |

Redesign of systems and policies may improve medication safety. The use of anti-infective medications is also a clear target for medication safety interventions. Improvements in working conditions will help with the effective implementation of medication safety interventions in neonatal and children’s intensive care settings. |

1 Introduction

Medication-related safety incidents are commonly reported as the most frequent incident type in hospitals and may be more likely to cause harm in children than in adults [1, 2]. The risk of experiencing these incidents may be greater for neonates and children admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) than for those on general wards because of factors such as the use of medicines associated with a high risk of harm, complicated and severe illnesses, complex weight-based dosing calculations, and heavy staff workload [3,4,5]. In addition, neonates and children admitted to ICUs may be pre-verbal or sedated, and this will affect their ability to prevent errors themselves [6].

Our recent systematic review indicated that the median prevalence of medication errors in paediatric ICUs was 14.6% of medication orders (interquartile range 5.7–48.8; three studies) and ranged from 5.5 to 77.9 per 100 medication orders in neonatal ICUs (two studies) [7]. However, data concerning the nature of medication errors and related adverse drug events in these settings were limited [7], as was research exploring the factors contributing to medication errors and related harm involving this high-risk patient population [8].

Detailed analysis of medication safety incident reports submitted to national reporting systems is important as greater understanding of their underlying antecedents helps guide the creation of improvement strategies and prioritisation of high-risk areas [9,10,11]. This would support international efforts to reduce preventable medication-related harm, as highlighted in the third World Health Organization (WHO) global patient safety challenge [12]. The strategic framework of this challenge includes incident reporting and learning as a key component.

Several countries, including the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Australia, have established national incident reporting systems [13], with the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) in England and Wales being the largest and most comprehensive worldwide [14]. The NRLS receives around 65,000 incident reports involving paediatric patients every year [9]. The NRLS is a good example of reporting systems that include the checklist of WHO Draft Guidelines for Adverse Event Reporting and Learning Systems [15, 16] and gather necessary information about incidents to enable success analysis and results dissemination with recommendations for safety improvements in healthcare systems. Incident reports submitted to the NRLS have been a source of information for those creating national patient safety alerts, rapid response reports, and medication safety guidance and research that aimed to reduce medication errors and related adverse drug events across different healthcare settings [5, 9, 17,18,19].

To our knowledge, no systematic analysis has yet examined the frequency and nature of, and factors contributing to, medication-related safety incidents reported from neonatal and children’s intensive care settings in UK national health service (NHS) hospitals. Previous studies have analysed incidents affecting paediatric primary care [9], adult critical care [20], and specific children’s inpatient units (e.g. neonatal units) [21]. These studies did not focus specifically on children in ICUs [22]. This study therefore aimed to examine the nature of, and factors contributing to, reported medication safety incidents in children’s intensive care settings across England and Wales over a 9-year period.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design, Settings, and Data Source

We carried out a retrospective mixed-methods study. This included analysis of data from medication-related incidents involving children (aged ≤ 18 years) admitted to hospital intensive care settings and submitted to the NRLS database from NHS organisations in England and Wales over a 9-year period (1 January 2010 to 31 December 2018). This period was chosen as it provides a sufficiently large dataset from recent years [23] and represents the period since mandatory reporting of serious harm and death incidents in NHS organisations was implemented (June 2010) [14].

Intensive care services for children can be divided into two fields: neonatal intensive care and paediatric critical care. In England and Wales, these are advanced and mature services providing critical care for both neonates (aged ≤ 28 days) and children (aged ≤ 18 years) with severe illnesses. There is substantial crossover between neonatal and paediatric intensive care because some services (e.g. congenital cardiac surgery) are provided on a national basis by specialised units. Critical care units provide care at a regional level, and annual admission rates have increased dramatically in recent years, partly because of an increased number of children being born prematurely or with complex medical conditions requiring intensive care [24]. Medication prescribing systems in these units are still largely paper based [25].

The NRLS defines a patient safety incident as “any unintended or unexpected incident that could have [led] or did lead to harm for one or more patients receiving healthcare” [26]. Anonymised incident reports related only to the use of medication in hospital paediatric critical care settings (paediatric/neonatal ICU or high-dependency units) were obtained from the NRLS. Because of the way the incident data from neonatal and paediatric intensive care are coded in the NRLS, it was impractical to separate the data into separate groups (neonatal and paediatric ICU) reliably, so the data were processed together.

2.2 Screening Process and Descriptive Analysis

Patient safety incidents are mostly reported by healthcare professionals in NHS organisations to their local risk management system using existing coding frameworks. The NHS organisations analyse, investigate, and anonymise incident reports and then submit them to the NRLS. All incidents reported by NHS organisations are aligned to the NRLS classification system [27]. In this study, we utilised the final codes recorded in the NRLS classification system without amendments by the research team, as described in Table 1 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM).

Two authors (AA and AS) independently screened all incidents and excluded those that were not medication related. In the first stage of data analysis, authors AA and AS coded medication(s) within each report using the British National Formulary for Children (BNF-C) categorisation system for medication classes [28]. Existing coded data from the NRLS framework for patient age, harm level, stage of medication use, and error category were extracted by AA and AS independently [27].

2.3 Contributory Factors Associated with Incidents Resulting in Patient Harm

In the second phase of the study, we reviewed all incidents reported to have caused patient harm (low harm, moderate harm, severe harm, and death) and conducted a content analysis of free-text incident descriptions (what happened, contributory factors, planned actions preventing reoccurrence) to understand potential contributory factors.

The contributory factors framework within the PISA (PatIent SAfety classification) system was applied to the selected incident reports [29]. This has been successfully used in studies examining NRLS medication incident data in primary care and mental health hospitals [9, 30,31,32,33]. To assess the feasibility of using the PISA system in our study, we applied the framework to a sample of the incidents and found that it captured all factors reported in the reports. One author (AA) then applied the PISA framework to each incident, and another author (AS) independently coded a random sample of 500 reports. Any disagreements between the reviewers were discussed until consensus was reached.

2.4 Data Analysis

2.4.1 Descriptive Analysis

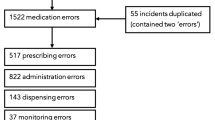

Descriptive analyses were conducted using STATA v15® [34]. We used frequency distributions and cross-tabulations to assess relationships between categories. As specific information about the location or speciality in which each incident occurred was lacking, the data were analysed according to age groups (Fig. 1).

We generated cross-tabulations between three patient age groups (age < 28 days, 1 month to 1 year, and 2–18 years), medication use process stage (supply, prescribing, advice, preparation/dispensing, administration, and monitoring), degree of harm (severity), and error type (Table 1 in the ESM). Further analysis explored the three most common BNF-C medication sub-classes involved across the medication use process stages. We also generated cross-tabulations between medications involved in reported incidents and the degree of harm to identify medication classes commonly involved with harmful events.

2.4.2 Content Analysis of Incidents Reported to have Caused Patient Harm

We applied the four main domains of the PISA classification system contributory factors list (patient, staff/individual, equipment, and organisation) and their sub-categories to the subset of incidents associated with harm. We also used Reason’s theoretical model of accident causation [35] to classify and present emerging contributory factor categories as (1) active failures (proximal causes of incidents) associated with individuals and (2) organisational (latent) systems failures as described in the reports. Information in the incident reports was insufficient to allow further categorisation of these failures (e.g. slips or lapses for active failures).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Findings

A total of 25,612 incident reports were obtained from the NRLS database. Of these, 25,567 (99.8%) were medication related and deemed eligible for inclusion. The remainder (0.2%) were excluded as they were not associated with the use of medication (e.g. infant feeds [breast milk, formula]). Figure 1 illustrates the screening process, including the capture of key information with each report.

Most incident reports involved infants aged < 28 days (n = 12,235 [47.9%]) and children aged between 1 month and 1 year (n = 9337 [36.5%]). Most reported incidents related to medicines administration (n = 13,668 [53.5%]) and prescribing (n = 7412 [29%]), with the most common error types being drug omission (n = 4812 [18.8%]), wrong dose (n = 4475 [17.5%]), and wrong frequency (n = 3193 [12.5%]) (Table 1).

Most incidents did not cause patient harm (n = 22,438 [87.8%]). Of 3129 (12.2%) harmful events, 2833 (90.5%) resulted in low harm, 286 (9.1%) caused moderate harm, and ten (0.31%) led to severe harm/patient death. The medications most commonly involved with incidents were anti-infectives (n = 6483 [25.4%]), followed by medications affecting nutrition and blood (n = 4505 [17.6%]) and agents acting on the central nervous system (n = 2613 [10.2%]). The majority of the 6483 incidents with anti-infectives involved antibacterial agents (n = 6002 [92.6%]), and aminoglycosides were the predominant subclass of these (n = 2470 [41.2%]). Table 1 shows the medication classes involved and the level of harm caused by each drug category.

3.1.1 Incidents Reported by Age Group (Age < 28 Days, 1 Month to 2 Years, and 2–18 Years)

The stages of the medication use process most commonly involved with incidents across all age groups was medication administration and prescribing, with drug omissions and wrong doses being the most common error types, as described in Table 2. Half of all harmful incidents (n = 1570/3129 [50.2%]) involved neonates (aged ≤ 28 days). Across both prescribing and administration stages, anti-infectives were the medications most commonly involved with reported incidents in the youngest age groups (< 28 days, n = 3399/9941 [34.2%] and 1 month to 2 years, n = 1427/7819 [18.2%]).

Across all medication use process stages, most of the incidents associated with anti-infective medications involved neonates aged ≤ 28 days (n = 4153/6483 [64.1%]). Aminoglycosides were the most commonly involved anti-infectives in this age group (n = 2007/4153 [48.3%]).

Across all age groups, harmful incidents most frequently occurred during medicines administration (n = 1955/3129 [62.5%]), involved medications commonly used to treat infections (n = 774/3129 [24.7%]), and involved wrong dosing (n = 608/3129 [19.4%]), drug omission (n = 606/3129 [19.4%]), and wrong frequency (n = 454/3129 [14.5%]) error types. Table 2 presents detailed information about the incidents reported in each age group, including commonly involved medication use process stages, levels of harm, drug classes, and error types.

3.2 Contributory Factors for Incidents Reported to have Caused Patient Harm

Of the 12.2% of harmful incidents, 1765 reports (56.4%) were included as they stated explicit contributory factors, whereas the remaining 1364 reports (43.6%) were excluded because descriptions of reported incidents in the free-text data were lacking.

Three main categories emerged from our content analysis that explored contributory factors: factors related to patients (n = 62/1765 [3.5%]), medical staff/individual factors (n = 1212 [68.7%]), and organisational factors (n = 482 [27.3%]). Some incident reports were related to impractical/faulty equipment or inadequate medication storage (n = 9 [0.5%]). Incidents that involved multiple contributory factors were common across the harmful incidents examined, and the most frequent combinations of these were staff- and organisational-related factors. Of the 1212 reported incidents that stated staff-related contributory factors, 807 (66.6%) incidents also involved organisational-related factors. Within these incidents, failures to follow/adhere to protocols or procedures because of a busy environment and work overload were common combinations.

3.2.1 Patient-Related Factors

Patient factors featured in incidents involving dose omissions and extravasation injuries. Challenging venous access in neonates led to dose omissions and consequent delays in treatment (example 1.1, Table 2 in the ESM). Given the undeveloped skin and fragile vasculature in this patient group, extravasation injuries were commonly reported in neonates despite correct cannula management procedures being followed.

3.2.2 Staff-Related Factors

Active failures were also associated with reported incidents. Staff factors included cognitive issues (e.g. perception, memory, or thinking), inadequate skill set/knowledge, and failure to follow/adhere to protocols or procedures. These active failures were frequently reported as being caused by organisational-related factors (latent conditions), such as work pressures and issues related to using paper-based prescribing systems (e.g. design of prescription or illegible handwriting). Figure 2 illustrates multi-directional interactions between active failures and latent conditions.

Failure to follow protocols or procedures (active failures), commonly involving prescribing, administering, or monitoring anti-infective medications, were the most common contributory factors directly involving staff. At times, staff did not monitor drug levels as recommended in protocols or follow safety procedures (e.g. independent double checking) for medication administration (example 2.1, Table 2 in the ESM). Other common contributory factors included cognitive issues, such as distraction, inattention, and oversight (example 2.2, Table 2 in the ESM).

Active failures (such as inappropriate cannula management) were also associated with some incidents. For example, lack of regular monitoring of cannula sites for early signs of extravasation injuries and failure to follow guidelines for administering intravenous medications contributed to some incidents. However, these active failures caused by individuals were commonly associated with medical staff being busy/overloaded by work (example 2.3, Table 2 in the ESM).

Errors (active failures) also occurred commonly during patient transfers between units or at handover between shifts. Most of these failures included poor-quality documentation, such as doses given but not documented or administration records lost during handover or patient transfer to ICU (example 2.4, Table 2 in the ESM). These active failures were notably reported as being associated with latent conditions such as heavy workloads (staff busy with other prioritised commitments) and inadequate patient record documentation systems.

Staff also reported errors in medication administration and monitoring due to inadequate knowledge, such as those with specific safety requirements in dosing or administration processes (e.g. phenytoin).

3.2.3 Organisational-Related Factors

The pressurised work environment within ICUs and a shortage of staff often contributed to medication omissions and failures to follow safety policies (example 3.1, Table 2 in the ESM). Incidents were also associated with errors during shift handovers due to inadequate protocols for this process and poor communication between medical staff (example 3.2, Table 2 in the ESM). Newly qualified staff working in the ICU but lacking training and familiarity with the setting’s policies and procedures were also described as a cause of incidents.

It became apparent that, in some cases, children, mostly neonates, were transferred routinely from other hospital areas (e.g. general or post-natal wards) to ICUs for single-dose administration before being returned. Incidents occurring during this process were often reported as being due to poor documentation of doses given in either the ward or the ICU or loss of medicine administration records (example 3.3, Table 2 in the ESM).

Other important contributory factors were categorised under poor continuity of care between ICU and hospital departments such as pharmacy and test laboratories. This involved delays in medicines supply from pharmacies, inadequate dispensing protocols, and delays in delivery of blood test results from laboratories (example 3.4, Table 2 in the ESM), which mainly caused dose omissions.

The design of prescription forms and use of paper-based documentation systems frequently contributed to the reported incidents. Ambiguous handwriting and poorly designed prescriptions were caused confusion that led to medication errors (example 3.5, Table 2 in the ESM). The unavailability of protocols and inadequate and variable guidelines were also notable contributory factors (example 3.6, Table 2 in the ESM).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first detailed analysis of medication-related incident data reported to a national database from neonatal and children’s intensive care settings. We found that incidents relating to medication administration and prescribing stages, and those involving medication omissions, wrong doses, and wrong frequency were the most common across all age groups. Neonates aged < 28 days were associated with most of the reported incidents and affected by most of the harmful incidents. The dominant contributory factors associated with these incidents included the challenging physiology of neonates, working conditions (e.g. heavy workload), variable or inadequate guidelines and systems, and poor continuity of care between ICUs and other hospital departments. Anti-infectives and medications affecting nutrition and blood were the medication classes most frequently involved in harmful and no-harm incidents.

We explored contributory factors for the reported incidents to help facilitate understanding about medication safety in this environment and illuminate the complexity of neonatal and children’s intensive care settings. Routine tasks (e.g. securing and monitoring venous access, checking and acting on drug levels, and administration double-checking procedures) were adversely affected by organisational factors such as staff shortages and consequent heavy workload, along with inadequate dosing guidelines and prescribing systems. Indeed, prescribing remains largely paper based in the UK [25]. The introduction of electronic prescribing systems has been associated with significant reductions in certain types of errors, such as illegible prescriptions [36]. Handwriting was one of the factors commonly involved with reported incidents in this study. In addition, clinical decision support is offered primarily in the form of administrative policies and guidelines, many of which are not standardised across interfaces of care. In a recent multi-centre study of the causative factors of prescribing errors in paediatric intensive care in England, a core feature of these decision support systems was their intellectual and physical inaccessibility. Furthermore, the only control against medication error in this setting was identified as the bedside nurse or unit pharmacist. However, these controls may be constrained by staff shortages and whether pharmacy services are available only during ‘office hours’ [8].

We found that the use of anti-infective medications is an area of risk to children in the ICU, particularly neonates aged < 28 days, with a high proportion of aminoglycosides implicated in incidents. This class of medicines is widely used to treat infections in neonates [37]. Aminoglycoside dosing and monitoring errors may cause serious and sometimes irreversible injury [38]. National co-ordinated guidance was implemented in 2010 to reduce these incidents with aminoglycosides in neonates [39]; however, the present study shows that incidents persist. As such, the use of safer alternative antimicrobials in critically ill neonates should be evaluated and safety measures in the use of these medications should be improved.

Common error types identified in our study, such as wrong doses and dose omissions, were notably associated with the pressurised ICU work environment, suggesting that improved staffing and workload is an important target. Studies have found that heavy workload and inadequate staffing, and related staff fatigue, were significantly associated with missed care for critically ill children [8, 40,41,42]. Children’s ICUs, including high-dependency beds in England and Wales, routinely exceed the standard limit of bed occupancy (reaching 85–100% occupancy), which should be < 85% and thus are often considered overloaded [43]. A better understanding of safe working conditions, and their influence on the implementation of medication safety improvements in these settings, is needed. The application of principles from the field of human factors and ergonomics could support the redesign of systems and processes to improve safety in complex work settings such as ICUs [44].

A meta-analysis conducted in 2020 [45] found that including pharmacists in hospital clinical areas to intervene in prescribing errors significantly reduced these errors in paediatric inpatients. Clinical pharmacy services are normally provided in hospitals in England and Wales, but the role of these services in medication safety in UK children’s intensive care settings is not well understood [45]. In addition, evidence on the clinical effectiveness (mitigating patient harm) of other strategies, such as computerised physician order entry and clinical decision support systems, remains limited [46]. Therefore, future controlled interventional studies are recommended with priority for critically ill neonates and anti-infective medications (particularly aminoglycosides) as high-risk areas.

In this study, we analysed a large dataset covering a 9-year period and generated important evidence of the nature of and factors contributing to medication safety incidents in children’s ICUs. This evidence may be used to support efforts to reduce medication errors and related patient harm in this area. The main limitation of this study is that we were unable to calculate the rate of events (e.g. per number of patients or prescriptions) as our data source was a national, fully anonymised, retrospective, and spontaneous incident-reporting data source [47]. Another limitation of this study relates to the poor quality of reporting of the speciality (neonatal or children’s ICU) where incidents occurred, which limited our ability to separate data from the two settings and to generate distinct improvement recommendations. Information about the medications involved with reported incidents was also missing. Therefore, the quality of reporting of information about incident location (e.g. neonatal ICU, paediatric ICU, or high-dependency unit) and medications involved could be improved in the NRLS reports to promote learning from incidents in future studies. In addition, we acknowledge that discrepancies may occur between reporter-allocated level of harm and the harm described within reported incidents [48]. This study did not reclassify reported incidents and used the NRLS classification system, so we did not examine variations between described and reported levels of harm in incidents.

5 Conclusion

This is the first exploration of the type, and contributory factors of medication-related safety incidents reported in children’s ICUs at a national level. We found that incidents were commonly associated with medication administration and prescribing stages. Most harmful and no-harm incidents involved neonates. Medication incidents occurring in this setting may have origins in challenging venous access in neonates, failure of ICU staff to follow safety protocols, notably, due to ICU excessive workload, inadequate policies or systems, and staff shortages. We identified areas for medication safety improvement in these settings, including transfer-of-care processes between wards and the ICU, medicines prescribing, and patient record documentation systems, as well as the use of anti-infective medications.

References

World Health Organization. Promoting safety of medicines for children. 2007. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/Promotion_safe_med_childrens.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 27 June 2020.

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, McKenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–20.

Skapik JL, Pronovost PJ, Miller MR, Thompson DA, Wu AW. Pediatric safety incidents from an intensive care reporting system. J Patient Saf. 2009;5(2):95–101.

Franke HA, Woods DM, Holl JL. High-alert medications in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(1):85–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181936ff8.

Conn RL, Tully MP, Shields MD, Carrington A, Dornan T. Characteristics of reported pediatric medication errors in Northern Ireland and use in quality improvement. Pediatr Drugs. 2020;22:551–560.

Manias E, Cranswick N, Newall F, Rosenfeld E, Weiner C, Williams A, et al. Medication error trends and effects of person-related, environment-related and communication-related factors on medication errors in a paediatric hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55(3):320–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14193.

Alghamdi AA, Keers RN, Sutherland A, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence and nature of medication errors and preventable adverse drug events in paediatric and neonatal intensive care settings: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2019;42(12):1423–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-019-00856-9.

Sutherland A, Ashcroft DM, Phipps DL. Exploring the human factors of prescribing errors in paediatric intensive care units. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(6):588. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315981.

Rees P, Edwards A, Powell C, Hibbert P, Williams H, Makeham M, et al. Patient safety incidents involving sick children in primary care in England and Wales: a mixed methods analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(1):e1002217.

Rees P, Edwards A, Powell C, Evans HP, Carter B, Hibbert P, et al. Pediatric immunization-related safety incidents in primary care: A mixed methods analysis of a national database. Vaccine. 2015;33(32):3873–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.068.

Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Arbous MS, De Vos R, De Jonge E. Incident and error reporting systems in intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;28(1):2–13.

World Health Organization. WHO Global patient safety challenge: medication without harm. 2017. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/medication-safety/en/. Accessed 17 Sep 2020.

Dovey S, Phillips R. What should we report to medical error reporting systems? BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13:322–3.

National Reporting and Learning System. Organisation patient safety incident reports. Secondary Organisation patient safety incident reports. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/learning-from-patient-safety-incidents/. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

World Health Organization. World alliance for patient safety: WHO draft guidelines for adverse event reporting and learning systems: from information to action. 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69797/WHO-EIP-SPO-QPS-05.3-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 24 Jan 2021.

World Health Organization. Patient safety incident reporting and learning systems: technical report and guidance. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010338. Accessed 1 Mar 2021.

The NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service. Archived patient (medication) safety alerts from the NPSA and SPS resources to support their implementation. 2018. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/patient-medication-safety-alerts-from-the-npsa-and-sps-resources-to-support-their-implementation/. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

National Patient Safety Agency. Safer lithium therapy. 2009. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2009-NRLS-0921-Safer-lithium-tmation-2010.01.12-v1.pdf. Accessed 25 Dec 2020.

National Patient Safety Agency. Actions that can make oral anticoagulant therapy safer. 2007. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/npsa-alert-actions-that-can-make-oral-anticoagulant-therapy-safer-2007/. Accessed 25 Jan 2021.

Thomas A, Taylor R. An analysis of patient safety incidents associated with medications reported from critical care units in the North West of England between 2009 and 2012. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(7):735–45.

Stuttaford L, Chakraborty M, Carson-Stevens A, Powell C. Patient safety incidents in neonatology: a 10-year descriptive analysis of reports from nhs england and wales. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(Suppl 1):A78.

Thomas A, Panchagnula U. Medication-related patient safety incidents in critical care: a review of reports to the UK National Patient Safety Agency. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(7):726–33.

National Reporting and Learning System. National patient safety incident reports: 21 March. 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/national-patient-safety-incident-reports-21-march-2018/. Accessed 18 Mar 2019.

Davis P, Stutchfield C, Evans TA, Draper E. Increasing admissions to paediatric intensive care units in England and Wales: more than just rising a birth rate. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(4):341–5.

Shemilt K, Morecroft CW, Ford JL, Mackridge AJ, Green C. Inpatient prescribing systems used in NHS Acute Trusts across England: a managerial perspective. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(4):213–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000905.

National Health Service. Patient safety incidents. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/report-patient-safety-incident/. Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

NHS Improvement. Guidance notes on National Reporting and Learning System official statistics publications. 2017. https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/1728/Guidance_notes_on_NRLS_officia_statistics_Sept_2017.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Paediatric Formulary Committee. British National Formulary for Children. Pharmaceutical Press, and RCPCH Publications, London: BMJ Group. 2020-21. http://www.medicinescomplete.com/. Accessed 4 Nov 2020.

Carson-Stevens A, Hibbert P, Avery A, Butlin A, Carter B, Cooper A, et al. A cross-sectional mixed methods study protocol to generate learning from patient safety incidents reported from general practice. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009079. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009079.

Cooper A, Edwards A, Williams H, Evans HP, Avery A, Hibbert P, et al. Sources of unsafe primary care for older adults: a mixed-methods analysis of patient safety incident reports. Age Ageing. 2017;46(5):833–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx044.

Gibson R, MacLeod N, Donaldson LJ, Williams H, Hibbert P, Parry G, et al. A mixed-methods analysis of patient safety incidents involving opioid substitution treatment with methadone or buprenorphine in community-based care in England and Wales. Addiction. 2020;115:2066–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15039.

Williams H, Donaldson SL, Noble S, Hibbert P, Watson R, Kenkre J, et al. Quality improvement priorities for safer out-of-hours palliative care: lessons from a mixed-methods analysis of a national incident-reporting database. Palliat Med. 2019;33(3):346–56.

Alshehri GH, Keers RN, Carson-Stevens A, Ashcroft DM. Medication safety in mental health hospitals: a mixed-methods analysis of incidents reported to the national reporting and learning system. J Patient Saf. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000815.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 15. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

Reason J. Human error. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

Prgomet M, Li L, Niazkhani Z, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI. Impact of commercial computerized provider order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication errors, length of stay, and mortality in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(2):413–22.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neonatal infection (early onset): antibiotics for prevention and treatment. 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg149. Accessed 12 May 2020.

Tzialla C, Borghesi A, Perotti GF, Garofoli F, Manzoni P, Stronati M. Use and misuse of antibiotics in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(sup4):27–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2012.714987.

National Patient Safety Agency. Safer use of intravenous gentamicin for neonates. London: NPSA. 2010. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100811064341/http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/search-by-audience/junior-doctor/?entryid45=66271. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

Tubbs-Cooley HL, Mara CA, Carle AC, Mark BA, Pickler RH. Association of nurse workload with missed nursing care in the neonatal intensive care unit. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(1):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3619.

Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Younger JB, Mark BA. A descriptive study of nurse-reported missed care in neonatal intensive care units. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(4):813–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12578.

Cho S-H, Kim Y-S, Yeon KN, You S-J, Lee ID. Effects of increasing nurse staffing on missed nursing care. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(2):267–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12173.

NHS England and NHS Improvement. Paediatric critical care and surgery in children review. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/paediatric-critical-care-and-surgery-in-children-review-summary-report-nov-2019.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2020.

Xie A, Carayon P. A systematic review of human factors and ergonomics (HFE)-based healthcare system redesign for quality of care and patient safety. Ergonomics. 2015;58(1):33–49.

Naseralallah LM, Hussain TA, Jaam M, Pawluk SA. Impact of pharmacist interventions on medication errors in hospitalized pediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01034-z.

Maaskant JM, Vermeulen H, Apampa B, Fernando B, Ghaleb MA, Neubert A, et al. Interventions for reducing medication errors in children in hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006208.pub3.

Palmero D, Di Paolo ER, Stadelmann C, Pannatier A, Sadeghipour F, Tolsa J-F. Incident reports versus direct observation to identify medication errors and risk factors in hospitalised newborns. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(2):259–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3294-8.

Macrae C. The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(2):71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004732.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Anwar A. Alghamdi, Richard N. Keers, Adam Sutherland, Andrew Carson-Stevens and Darren M. Ashcroft have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Availability of data and material

NHS Improvement approved the sharing of the NRLS data with the University of Manchester. As per the data sharing agreement (DSA.5047), access to data is only available after approval by NHS Improvement (https://www.england.nhs.uk/contact-us/contact-nhs-improvement/).

Ethics approval

The National Patient Safety Team at NHS England and NHS Improvement approved the study protocol and the sharing of the NRLS data with the University of Manchester (approval reference: DSA.5047).

Consent

Data utilised in this study were fully anonymised prior to being made available to the research team under an approved data sharing agreement without individual consent from patients and practitioners described in the incident reports.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Anwar A. Alghamdi contributed to the study design and the analysis and interpretation of data and led the data screening, inclusion and exclusion assessment, data coding and analysis, and manuscript writing. Richard N. Keers and Darren M. Ashcroft contributed to the study design and interpretation of data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and supervised AAA throughout his PhD programme. Adam Sutherland was involved in the data screening, coding, and analysis; inclusion and exclusion assessment; and review and revision of the manuscript. Andrew Carson-Stevens was involved in the data analysis and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alghamdi, A.A., Keers, R.N., Sutherland, A. et al. A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Medication Safety Incidents Reported in Neonatal and Children’s Intensive Care. Pediatr Drugs 23, 287–297 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00442-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00442-6