Abstract

Background

To protect children from harm, clinicians, educators, and patient safety champions need information to direct improvement efforts. Critical incident data could provide this but are often disregarded as a source of evidence because under-reporting makes them an inaccurate measure of error rates.

Objective

Our aim was to identify key targets for pediatric healthcare quality improvement. The objective was to evaluate the types, characteristics, and areas of risk within reported medication errors in pediatric patients.

Methods

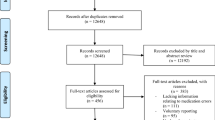

We conducted a retrospective study of a large regional dataset of 1522 pediatric medication errors reported from secondary care between 2011 and 2015, including all hospitals and community pediatric settings in Northern Ireland. The following characteristics were included: error severity, patient age, drug involved, error type, and area of practice. Two academic pediatricians, a senior medicines governance pharmacist, a Reader in Pharmacy Practice, and a Professor of Medical Education analyzed the data. Validity checks included comparing the findings against key published literature and discussion by a practitioner panel representing five multidisciplinary stakeholder groups.

Results

Neonates, particularly in intensive care, were implicated in 19% of all errors. The medications most represented in risk were antimicrobials, paracetamol, vaccines, and intravenous fluids. The error types most implicated were dosing errors (32%) and omissions (21%).

Conclusions

Incident reports identified neonates, a shortlist of drugs, and specific error types, associated with modifiable behaviors, as priority improvement targets. These findings direct further study and inform intervention development, such as specific training in calculations to prevent dosing errors. Involving experienced practitioners both endorsed the findings and engaged the practice community in their future implementation. The utility of incident reports to direct improvement efforts may offset the limitations in their representativeness.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Donaldson LJ, Kelley ET, Dhingra-Kumar N, Kieny MP, Sheikh A. Medication without harm: WHO’s third global patient safety challenge. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1680–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31047-4.

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/00132586-200206000-00041.

Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD, Wong ICK, Chi I, Wong K. The incidence and nature of prescribing and medication administration errors in paediatric inpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:113–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.158485.

Cass H. Reducing paediatric medication error through quality improvement networks; where evidence meets pragmatism. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(5):26–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309007.

Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD, Yeung VWS, Khaki ZF, Wong ICK. Systematic review of medication errors in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(10):1766–76. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1G717.

Wong ICK, Ghaleb MA, Franklin BD, Barber N. Incidence and nature of dosing errors in paediatric medications: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2004;27(9):661–70. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427090-00004.

Rinke ML, Bundy DG, Velasquez CA, et al. Interventions to reduce pediatric medication errors: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134:338–60. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3531.

Wong ICK, Wong LYL, Cranswick NE. Minimising medication errors in children. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(2):161–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.116442.

Lesar TS. Tenfold medication dose prescribing errors. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1833–9. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1C032.

Suresh G, Horbar JD, Plsek P, et al. Voluntary anonymous reporting of medical errors for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1609–18. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.113.6.1609.

Simpson JH, Lynch R, Grant J, Alroomi L. Reducing medication errors in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(6):F480–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2003.044438.

Cote CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: a critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4):805–14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.4.805.

Ross LM, Wallace J, Paton JY, Wallace J. Medication errors in a paediatric teaching hospital in the UK: five years operational experience. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(6):492–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.83.6.492.

Cousins DH, Gerrett D, Warner B. A review of medication incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning System in England and Wales over 6 years (2005–2010). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:597–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04166.x.

Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public health Res. 2013;2(3):27. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2013.e27.

Kozer E, Scolnik D, Jarvis AD, Koren G. The effect of detection approaches on the reported incidence of tenfold errors. Drug Saf. 2006;29(2):169–74. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200629020-00007.

Sari AB, Sheldon TA, Cracknell A, Turnbull A. Sensitivity of routine system for reporting patient safety incidents in an NHS hospital: retrospective patient case note review. BMJ. 2007;334:79. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39031.507153.AE.

Macrae C. The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(2):71–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004732.

Noble DJ, Pronovost PJ. Underreporting of patient safety incidents reduces health care’s ability to quantify and accurately measure harm reduction. J Patient Saf. 2010;6:247–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181fd1697.

Royal College of Physicians. Supporting junior doctors in safe prescribing. London: RCP; 2017. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/supporting-junior-doctors-safe-prescribing. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

World Health Organization. Conceptual Framework for the International Classification of Patient Safety. Geneva: WHO; 2009. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Battles JB, Lilford RJ. Organizing patient safety research to identify risks and hazards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii2–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii2.

Department of Health. An organisation with a memory—report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS. London: TSO; 2000. https://www.webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105144251/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4065086.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Walsh K. When I say Triangulation. Med Educ. 2013;47(9):866. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12241.

Agency National Patient Safety. Review of patient safety for children and young people. London: NPSA; 2009.

Subhedar NV, Parry HA. Critical incident reporting in neonatal practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95(5):F378–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.137869.

Shaw KN, Lillis KA, Ruddy RM, et al. Reported medication events in a paediatric emergency research network: Sharing to improve patient safety. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(10):815–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-201642.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Intravenous paracetamol (Perfalgan): risk of accidental overdose, especially in infants and neonates. Drug Saf Updat. 2010;3:2–3.

National Patient Safety Agency. Overdose of intravenous paracetamol in infants and children | Signal 1293F. London: NPSA; 2010. http://www.webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20171030130125/http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/clinical-specialty/paediatrics-and-child-health/?entryid45=83757. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

National Patient Safety Agency. Safer use of intravenous gentamicin for neonates. London: NPSA; 2010. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2010-NRLS-1085-Safer-use-of-inonates-2010.02.03-v1.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Armon K, Riordan A, Playfor S, Millman G, Khader A. Hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia during intravenous fluid administration. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(4):285–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.093823.

Hyponatraemia Inquiry Team. The inquiry into hyponatraemia-related deaths report. 2018. http://www.ihrdni.org/Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Feikema SM, Klevens RM, Washington ML, Barker L. Extraimmunization among US children. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283(10):1311–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.10.1311.

World Health Organization. Global manual on surveillance of adverse events following immunization. 2014. http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/publications/Global_Manual_revised_12102015.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Rees P, Edwards A, Powell C, et al. Pediatric immunization-related safety incidents in primary care: A mixed methods analysis of a national database. Vaccine. 2015;33(32):3873–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.068.

Kaushal R, Goldmann DA, Keohane CA, et al. Medication errors in paediatric outpatients. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e30. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2008.031179.

Sutcliffe K, Stokes G, O’Mara-Eves A, et al. Paediatric medication error: a systematic review of the extent and nature of the problem in the UK and international interventions to address it. London: EPPI-Centre; 2014. https://www.eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/Paediatric%20medication%20error%202014%20Sutcliffe%20report.pdf?ver=2014-11-20-161504-377. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Huynh C, Wong ICK, Correa-West J, et al. Paediatric patient safety and the need for aviation black box thinking to learn from and prevent medication errors. Pediatr Drugs. 2017;19:99–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-017-0214-8.

Koren G, Barzilay Z, Greenwald M. Tenfold errors in administration of drug doses: a neglected iatrogenic disease in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1986;77:848–9.

Keers RN, Williams SD, Cooke J, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence and nature of medication administration errors in health care settings: a systematic review of direct observational evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(2):237–56. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1R147.

Poder TG, Maltais S. Systemic analysis of medication administration omission errors in a tertiary-care hospital in Quebec. Health Inf Manag J. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358318781099(ePub Jun 18).

Williams H, Edwards A, Hibbert P, et al. Harms from discharge to primary care: mixed methods analysis of incident reports. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(641):e829–37. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X687877.

Rees P, Edwards A, Powell C, et al. Patient safety incidents involving sick children in primary care in england and wales: a mixed methods analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002217.

Snijders C, van Lingen RA, Klip H, et al. Specialty-based, voluntary incident reporting in neonatal intensive care: description of 4846 incident reports. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(3):F210–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.135020.

Olsen S, Neale G, Schwab K, et al. Hospital staff should use more than one method to detect adverse events and potential adverse events: incident reporting, pharmacist surveillance and local real-time record review may all have a place. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2007;16(1):40–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.017616.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, whose Research Fellowship supported Richard Conn in conducting this work. We also thank Professor Karen Mattick for comments on a draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Richard Conn and Angela Carrington. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Richard Conn. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Richard Conn, Mary Tully, Michael Shields, Angela Carrington, and Tim Dornan have no conflicts of interest that are relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material

Data were obtained with full NHS Ethics and Trust Governance approval. Data were fully anonymized prior to being made available to the research team. As data contain narrative information about patients and hospital staff, we have not openly published the dataset; access to data is available on request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript.

Ethics approval

The research was deemed eligible for Proportionate Review by the first available committee. It was approved by the Proportionate Review Subcommittee of the East Midlands—Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/EM/0353).

Consent to participate/consent for publication

As this study used aggregated, anonymized incident data only, individual consent from patients and practitioners described in reports was not sought.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conn, R.L., Tully, M.P., Shields, M.D. et al. Characteristics of Reported Pediatric Medication Errors in Northern Ireland and Use in Quality Improvement. Pediatr Drugs 22, 551–560 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-020-00407-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-020-00407-1