Abstract

Over the last 50 years, the Indian population aged 50 years and above (older adults) has quadrupled and is expected to comprise 404 million people in 2036, representing 27% of the country’s projected population. Consequently, the contribution of chronic disease to older adults’ total burden of diseases in India is likely to escalate. Disease burden is notably amplified by immunosenescence, a deterioration of the immune system that develops with age, leading to increasing susceptibility to infectious diseases and other comorbidities. Older adults with infectious diseases have a higher incidence and likelihood of life-threatening comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, stroke, myocardial infarction, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Therefore, immunization of older adults through vaccination might greatly reduce the burden imposed by vaccine preventable infectious diseases in this population. Here, we review evidence relevant to the disease burden among adults aged ≥ 50 years in India, and existing vaccination recommendations. Furthermore, we suggest a set of routine vaccinations for healthy older adults in India. There is a clear mandate to recognize the contributions of older adults to society and embrace strategies promoting healthy aging, which is described by the World Health Organization as the process of developing and maintaining functional ability and well-being in older age. Increasing vaccination awareness and coverage among older adults is an important step in that direction for India.

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the last 50 years, the population of India aged ≥ 50 years (older adults) has quadrupled and is expected to increase further. |

People aged ≥ 50 years are prone to infectious diseases due to immunosenescence and other declining physiological functions. |

Increasing vaccination awareness and coverage among older adults in India is an important step towards healthy aging. |

1 Introduction

Projections show that India will soon surpass China as the most populous country in the world [1]. In parallel to India’s rapid socioeconomic development in these last decades, life expectancy at birth has substantially improved to 70.3 years for women and 66.9 years for men in 2016; the corresponding figures in 1990 were 59.7 and 58.3 years [2]. Over the last 50 years, therefore, the Indian population aged ≥ 50 years has quadrupled [1], exceeding 260 million persons in 2020 [1], and is expected to increase more in the near future [1, 3]. As a consequence, the contribution of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes mellitus to the total disease burden increased from 30% in 1990 to 55% in 2016 [2]. Similarly, the susceptibility to infectious diseases along with other comorbidities also increases with increasing age [4]. The globalization of economies and the high frequency of international travel has also greatly increased the probability of exposure to infectious agents, both within and between countries [5] as dramatically exemplified by the rapid worldwide spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The demographic and socioeconomic changes demand adaptation of health strategies and policies to promote health through increasing access to vaccination of older adults. Immunization beyond infancy is a global priority for the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. Several industrialized countries have developed immunization plans for older adults to increase suboptimal vaccination coverage but such plans, even when fully implemented, need time to produce optimal results. Nevertheless, such precautionary policies have been largely neglected in low-income and middle-income countries [4]. This situation has been highlighted by the WHO and the organization is calling for countries across the world to implement urgently needed ‘Healthy Aging’ strategies and to “align health systems to the needs of the older populations” [6]. In India, national immunization programs focus solely on pediatric immunization, neglecting preventive immunization for older adults [7]. The available adult immunization recommendations are limited in their applicability and focus on the older adult, while others focus on special populations with specific morbidities [7, 8].

In this review, we therefore discuss the importance of immunization in older adults, and the relevance of vaccination towards healthy aging in India. However, no single definition or standard numerical criterion for the term ‘old’ exists [4, 9]. In developed countries, becoming eligible for an occupational retirement pension is often used as the informal cut-off for “old age”, while a shorter life expectancy lowers the threshold for being “old” in Africa [9]. The 2007 WHO meeting on immunization in older adults defined older adults as “people in the second half of life, i.e. over half of the life expectancy” for their respective country [4]. In this review, we follow a more conservative definition for older age, in agreement with the International Council on Adult Immunization definition of older adults [10], and thus focus on the population aged ≥ 50 years. The incidence of comorbidities is higher in this age group, and therefore this is the population in greater need of preventive healthcare [10, 11]. We also summarize existing adult immunization policies and discuss the older population’s susceptibility to infectious diseases. Furthermore, we summarize existing barriers, challenges, opportunities, and benefits of older adult vaccination. Figure 1 elaborates on the findings in a form that could be shared with patients by healthcare individuals.

2 Vaccination Coverage in India

In India, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare conducts approximately nine million sessions of vaccinations every year, targeting one of the largest populations in the world consisting of 27 million newborns, 100 million children aged 1–5 years, and 30 million pregnant women [12]. In 2019, after having implemented for the past 10 years a series of interventions such as strengthening surveillance and cold chain systems and improving communication strategies [7], high coverage rates were achieved in children by age 35 months: 92% for Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, 91% for three doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine, 90% for three doses of polio vaccine, and 95% for the first dose of the measles vaccine [13].

Very little data are available for older adult immunizations, and vaccine uptake. Adult vaccination coverage even among at-risk populations, such as healthcare workers, appears negligible [7, 8]. Lahariya and Bhardwaj report that in an adult vaccination center in Jodhpur, pre-exposure vaccination coverage was 8% for hepatitis B, 7% for pneumococcal, 3% for typhoid, and 1% for influenza [7]. Four percent of adults had received one or some of the following vaccinations: meningococcal, hepatitis A, varicella-zoster, and polio [7]. Vaccination coverage post-exposure was 42% for tetanus toxoid vaccines, and 20% for rabies vaccination [7].

3 Older Population and Burden of Disease in India

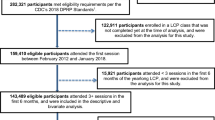

According to the 2019 findings of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Technical Group on Population Projections, the older population, aged ≥ 50 years, is expected to double from 193 million in 2011 to 404 million in 2036 [3]. Consequently, the age group of older adults aged ≥ 50 years will account for 27% of the total population in India by 2036, while the proportion of the total population of the age group < 15 years will decrease from 31% in 2011 to 20% in 2036 (Fig. 2) [3].

Projections of population distribution by age group in India based on the 2011 Census data; years 2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, 2031, and 2036. Created from: Census of India 2011. Population projections for India and States 2011–36. Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections, November 2019. National Commission on Population. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India [3]

The 2017 Report on Medical Certification of Cause of Death of the Ministry of Home Affairs mentions that, among older adults aged > 45 years, CVD was the leading cause of death, with a range from 35.9% in the 45–54 years of age group to 44.5% in ≥ 70 years [14]. The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016 reported that 28.1% of total deaths in India were caused by CVD, primarily ischemic diseases (17.8% of total deaths), followed by stroke (7.1%), hypertension (1.3%), and rheumatic heart disease (1.1%) [15]. Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study estimates, CVD, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases have been increasing. The prevalence of CVD reached 54.5 million in 2016 from 25.7 million in 1990 [15]. Diabetes estimates for 2016 were 65 million, a two-fold increase from the 26.0 million in 1990 [16]. The prevalence of overweight among adults also substantially increased across all states, from 9.0% in 1990 to 20.4% in 2016 [16]. These increases in the prevalence of chronic diseases will most likely lead to increased infectious diseases burden as well, given that chronic diseases are associated with an increased risk for infectious diseases [17,18,19,20]. Among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, asthma, chronic kidney disease, or inflammatory bowel disease, older adults aged ≥ 50 years are at least two times more likely to experience herpes zoster (HZ) [21].

Furthermore, older populations are vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) such as influenza, pneumococcal, HZ, and tetanus [22]. The 2004 Global Burden of Disease Project estimated that infectious diseases in India accounted for approximately 30% of the total disease burden [23].

It is also shown that vaccination protects older adults with chronic conditions from developing complications and significantly reduces the frequency of hospitalizations [24], intensive care and cardiac care unit admissions, and mortality [25]. Moreover, worldwide evidence clearly demonstrates that older adult patients with VPDs are at an increased risk of experiencing life-threatening chronic comorbid diseases compared with their peers without VPDs [26]. Coronary artery disease, arrhythmias, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, myocardial infarction, anxiety, depression, stroke, and transient ischemic attack are more frequent among older adults aged ≥ 50 years with a history of HZ compared with their peers without a history of HZ [27, 28]. Large studies conducted in the USA have shown an association between HZ and the risk of stroke [27, 29]. Asthma is more frequent among patients with HZ than among non-HZ patients [30]. Following HZ, older adults aged ≥ 50 years have a 38% [29] to 53% increased likelihood of experiencing a stroke [27], and a 60% increased likelihood for a transient ischemic attack compared with peers without a history of HZ [29]. Neurologic complications occur in 25–70% patients with infectious endocarditis [31]. Most of these are cerebrovascular in nature, mostly corresponding to ischemic (70%) or hemorrhagic (15%) strokes [31]. Bacterial meningitis and tuberculous meningitis may also lead to stroke in 17–43% and 26% of cases, respectively [31].

3.1 Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in India

Based on the limited data available to the WHO in 2017, a significant proportion of the world’s cases of some VPDs occurred in India: 60% of diphtheria cases, 40% of tetanus cases, 17% of pertussis cases, and 17% of rubella cases [8]. Although it is reasonable for the second most populous country in the world to have a high proportion of global cases, the fact that the prevalence of certain VPDs were 2.2–3.4 times higher than the global prevalence gives cause for concern [8]. In the absence of real-time infectious disease reporting [23], there are no adequate data on the overall disease burden due to VPDs in the Indian population. Therefore, the actual VPD disease burden is expected to be higher than reported because of poor surveillance networks, under-diagnosis, and under-reporting [23].

Although epidemiological data stratified by age are not available, there are several reports on VPD outbreaks in recent years (varicella, diphtheria, hepatitis A, influenza, measles) showing that adults were the most frequently affected age group [8]. All other available epidemiological data on VPDs in India refer only to the whole population. It can be assumed, however, that much of the burden of some VPDs is in adults: data available for human papillomavirus disease estimate that every year there are about 97,000 new cases, and 60,000 deaths in human papillomavirus-related cancer [32]. Likewise, regarding HZ, hospital data published within the last 5 years suggest that a substantial proportion of the total population of patients with HZ could be aged ≥ 40 years [33,34,35,36,37].

An analysis of influenza surveillance data from 2010 to 2013 showed that 58.6% of influenza-related respiratory deaths and 52.9% of influenza-related circulatory deaths were among adults aged ≥ 65 years [38]. Influenza vaccination has a low priority in India, and as such is labeled by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare as ‘desirable’ for those aged ≥ 65 years [38]. Older adults are also at an increased risk for pneumococcal disease, including meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis [39, 40].

4 Healthy Aging

Aging is the lifelong process of progressive functional and structural changes in the physical, mental, and social status of individuals [41]. With increasing chronological age, the body organs change at different rates [42]. Neuronal [42, 43] and musculoskeletal [43] system deteriorations influence an individual’s strength and mobility and induce frailty. Multiple organ systems such as the lungs, the gastrointestinal system, and the cardiovascular system are undergoing structural and functional modifications through aging [42]. The deteriorations induced are not linear and have differential impacts on the intrinsic capacities of individuals, i.e., the combination of mental and physical capacities [6]. Frailty as a combination of decreased physical activity, energy, muscle weakness, unintentional weight loss, and exhaustion might develop at later life stages [43]. Some older adults might become clinically frail while others might not share such an experience [43]. These trajectories are also influenced by lifestyle conditions, the social and political environment, and their interactions [6].

As the global population increases both in size and in age, it is important for societies to understand the challenges and opportunities of this epidemiological trend and embrace healthy aging, defined by the WHO as the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age [6, 44]. Furthermore, with increasing life expectancy, more family generations are alive at the same time, family members may be more widely distributed as younger generations might migrate for work, and the trend is that an increasing number of older people live alone instead of together with children, which used to be the norm [44]. Consequently, these people need to feel confident that they have a healthcare sector at their disposal that provides all the necessary provisions to help them attain and maintain good health [44].

Unfortunately, according to the WHO, older adults around the world have poorer health trajectories than anticipated [6]. Specifically for India, in the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts 2013 Survey on Global Ageing, the percentage of participants reporting self-rated good health ranged from 12% among those aged > 80 years to 37% among those aged 50–59 years; only 31% of the overall population of older adults aged ≥ 50 years rated their health as ‘good’ [45].

Most health problems in older adults have their origin in preventable conditions, or conditions that could have been delayed, as pointed out by the WHO [6] and described here. Providing primary healthcare to older people that would slow or reverse declines in intrinsic capacities would help them maximize their functional abilities, in accordance with the WHO Healthy Aging strategic objectives [6]

4.1 Immune System and Aging

The immune system evolves from birth throughout life [46]. With aging, innate and adaptive immune cells undergo a number of alterations that affect their function and therefore the immune system response [47, 48]. Under a life-long adaptive process, the immune system constantly remodels to ensure host survival [42]. At birth, the immune system is still immature and starts developing to become more efficient during the childhood period, in part following challenges from bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi [46]. At birth, the innate immune system is not fully functioning, and infants are at an increased risk of infectious diseases [46]. Furthermore, infant T cells of the adaptive immune system differ significantly from those in adulthood, as they have responded to few stimuli while in utero [46]. Gradually, the immune system matures to offer improved protection against infectious diseases; with the aid of vaccinations during childhood, the immune system is stimulated without most of the possible negative effects of natural infections [46]. At this point, it should be noted that most older adults in India aged ≥ 50 years have probably never received any childhood vaccinations, as the Expanded Programme of Immunization was first implemented in India in 1978 [8].

As we age, many biological phenomena, including gradual alterations to immune system cell levels, cause immune system remodeling and changes, some leading to immunosenescence, a deterioration in the functions of the immune system (Fig. 3) [49]. Immunosenescence has been associated with increased susceptibility to infectious, neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and autoimmune diseases [42]. The clinical significance of immunosenescence is illustrated by the higher burden of infectious diseases in older adults than in young individuals. For instance, in young ages, CD4+ T-cell responsiveness to Bordetella pertussis is increased especially compared with decayed older age responsiveness [50]. Current evidence from the field of influenza vaccines indicates CD8+ T cells function as a key target towards increasing vaccine effectiveness in older adults [51].

Biological aging and its impact on the functionality of organs and the immune system. Created from [42]. NK natural killer

Gradual development of subclinical inflammation, known as ‘inflammaging’, may be at least partially contributing to frailty and increased susceptibility to chronic diseases associated with aging such as atherosclerosis, obesity, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases [49]. All modifications together lead to a decreased response to new infections, endogenous injuries, and a decrease in immunity to previously encountered pathogens [49, 51].

Overall, the mortality rate due to infectious diseases is estimated to be three times higher among older adults than in younger adults [46]. In a study in New Delhi, the mortality of patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae aged > 50 years was nearly 2.5 times higher than in patients aged < 50 years [22]. For example, S. pneumoniae was the most common bacterium among older adults with community-acquired acute bacterial meningitis in a study in Puducherry in India [22].

Nevertheless, an effective immune response can be generated in older adults if the immune system is appropriately activated, for instance through vaccination [52, 53]. It is therefore highly relevant to ascertain older adults’ vaccination coverage, especially among the presumably unvaccinated Indian population of older adults.

5 Recommendations for Older Adult Vaccination

Table 1 summarizes selected vaccination recommendations that involve older adults aged ≥ 50 years and further presents the respective authors’ proposal. Older adult immunization in India is barely accounted for in national vaccination recommendations beyond WHO recommendations for routine immunizations (Table 1) [54]. This is not the case, for example, in other countries in the developed world. For example, in adult vaccination recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA, the adult vaccination program begins at 19 years of age and covers the whole life span [55]. In India, the only adult vaccinations included in the Universal Immunisation Program are tetanus and diphtheria during pregnancy and Japanese encephalitis in certain endemic areas [7, 8]. Medical societies have introduced additional vaccination guidelines. However, these mainly involve at-risk adults, and discrepancies between them do not allow the dissemination of clear vaccination guidance for adults [8]. Professional association guidelines in India for adult vaccination include the pneumococcal and influenza vaccination from the Geriatric Society of India [56], the Association of Physicians of India [57,58,59,60], the Research Society for Study of Diabetes in India, the Indian Society of Nephrology, and the Indian Medical Association [61, 62].

6 Barriers and Opportunities

Some barriers to the immunization of older adults in India are systemic and therefore relevant to any type of vaccination, regardless of the age groups targeted [63,64,65]. Such barriers include issues of disease surveillance systems, vaccine confidence, and access to vaccines (Fig. 4). Regarding surveillance, no real-time disease reporting [23] system has been implemented for VPDs in India. Moreover, VPDs are not included in any other formal surveillance system [23]. By surveillance, we consider both disease and vaccination coverage monitoring. Therefore, the VPD burden or vaccination coverage among older adults can only be based on data collected in studies from patients attending primary health centers representing only a small fraction of the overall patient population [23], which are inadequate to cover the whole country.

Prospective epidemiological studies could help improve our knowledge on the epidemiological profile of VPDs among older adults in India. Creating a network of collaborating institutes and hospitals across rural and urban regions of the country would improve multidisciplinary scientific collaboration and facilitate guideline harmonization (Fig. 4). A lack of simple diagnostic tools with non-sophisticated instruments or training for some VPDs [63] could also be addressed within harmonized consensus guidelines.

Other barriers notably include access to vaccines and difficulties in reaching isolated and mobile populations, and vaccine hesitancy because of misinformation [64]. Provision of transparent information on the effectiveness and safety of vaccines would help combat vaccine hesitancy [66]. Raising a healthcare provider’s awareness also has potential to substantially improve vaccination coverage [66]. We suggest that specialized training themes be designed for healthcare providers, and vaccination campaigns be tailored to citizens aged ≥ 50 years [67]. Senior citizens should be able to benefit from their country’s healthcare resources and vaccine access should be ensured for them.

Finally, there is also a need for cost-effectiveness data evaluating vaccinations to support decision making. We believe that such estimations should take into account the role of older adults in society as family members and workers, a perspective that would help reverse the existing negative bias towards older adult vaccinations by showing its full value (Fig. 4). Moreover, cost-effectiveness analyses in this setting should include complications of infectious diseases among unvaccinated individuals, burden of the chronic diseases, polypharmacy, loss of employment and independence, and costs of rehabilitation centers [43].

7 Conclusions

Historically, the primary focus of vaccinations was on immunizations during childhood and pregnancy [5, 7]. However, after having achieved high vaccination rates in these populations, it is time to shift our attention to another rapidly growing and also vulnerable population: older adults. In the age of a globalized economy, with rapidly improving healthcare knowledge and extended life expectancy, ‘older adults’ constitute an increasingly populous age group that is active and productive, with highly specific skills accumulated over many years. Moreover, they are central members of families and an integral part of societies. One of the biological effects of aging, however, is the decline in intrinsic physical resilience, making older adults more prone to infectious and chronic diseases, the burden of which can be reduced by preventive medicine [4]. In India, the public healthcare system is overwhelmed by offering care to patients, many of whom have diseases that could have been prevented [23]. A framework promoting healthy aging, introduced by the WHO, encourages countries to implement strategies promoting good health for all [41].

It is now the time to consider older adult immunization as a new healthcare priority [68]. Adult immunization is a needed key component of a country’s approach to building a healthcare program inclusive for all populations [4]. Any such program should consider factors that will promote its successful implementation because it has been shown in countries with established adult vaccination recommendations that vaccination coverage is frequently suboptimal [68, 69]. Especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO is recommending VPD vaccination programs for older adults, and for high-risk populations, as this will help free up beds that would otherwise be occupied by patients with pneumococcal diseases, complications of influenza, and pertussis. It would also help avoid the possibility of coinfections with simultaneous occurrence of some of these VPDs and COVID-19, and free up medical supplies and medications for the treatment of patients with COVID-19 [70].

References

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ and https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_10KeyFindings.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. India: Health of the Nation's States: the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative. New Delhi, India: ICMR, PHFI, and IHME. 2017. https://phfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2017-India-State-Level-Disease-Burden-Initiative-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2020.

Census of India 2011. Population projections for India and States 2011-2036. Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections, November 2019. National Commission on Population. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/Report_Population_Projection_2019.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Teresa Aguado M, Barratt J, Beard JR, Blomberg BB, Chen WH, Hickling J, et al. Report on WHO meeting on immunization in older adults: Geneva, Switzerland, 22–23 March 2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(7):921–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.029.

Mehta B, Chawla S, Kumar V, Jindal H, Bhatt B. Adult immunization: the need to address. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(2):306–9. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.26797.

World Health Oganization. The Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020-2030. Available from: https://www.who.int/ageing/en/ A. 10 Priorities for a Decade of Action on Healthy Ageing https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-ALC-10-priorities.pdf?ua=1 B. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 July 2020.

Lahariya C, Bhardwaj P. Adult vaccination in India: status and the way forward. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(7):1508–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1692564.

Dash R, Agrawal A, Nagvekar V, Lele J, Di Pasquale A, Kolhapure S, et al. Towards adult vaccination in India: a narrative literature review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(4):991–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1682842.

World Health Organization. Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/. Accessed 30 June 2020.

Privor-Dumm LA, Poland GA, Barratt J, Durrheim DN, Deloria Knoll M, Vasudevan P, et al. A global agenda for older adult immunization in the COVID-19 era: a roadmap for action. Vaccine. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.082.

Esposito S, Principi N, Rezza G, Bonanni P, Gavazzi G, Beyer I, et al. Vaccination of 50+ adults to promote healthy ageing in Europe: the way forward. Vaccine. 2018;36(39):5819–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.041.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Immunization handbook for health workers. 2018. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/Guildelines_for_immunization/Immunization_Handbook_for_Health_Workers-English.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2020.

WHO. India: WHO and UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage: 2018 revision. 2019. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/ind.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2020.

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Report on medical certification of cause of death. 2017. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Documents/mccd_Report1/MCCD_Report-2017.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2020.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative CVDC. The changing patterns of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):e1339–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30407-8.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Diabetes Collaborators. The increasing burden of diabetes and variations among the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):e1352–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30387-5.

Nørgaard M. Risk of infections among adult patients with haematological malignancies. Open Infect Dis J. 2012;M4:46–51. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874279301206010046.

Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang HH, Johnsen SP, Schonheyder HC, Sorensen HT. Diabetes mellitus as a risk and prognostic factor for community-acquired bacteremia due to enterobacteria: a 10-year, population-based study among adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(4):628–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/427699.

Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang HH, Johnsen SP, Sorensen HT, Schonheyder HC. Diabetes and outcome of community-acquired pneumococcal bacteremia: a 10-year population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):70–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.1.70.

Dooley KE, Chaisson RE. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):737–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70282-8.

Forbes HJ, Bhaskaran K, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Clayton T, Langan SM. Quantification of risk factors for herpes zoster: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2014;348:g2911. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2911.

Verma R, Khanna P, Chawla S. Vaccines for the elderly need to be introduced into the immunization program in India. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(8):2468–70. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.29254.

John TJ, Dandona L, Sharma VP, Kakkar M. Continuing challenge of infectious diseases in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):252–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61265-2.

Sung LC, Chen CI, Fang YA, Lai CH, Hsu YP, Cheng TH, et al. Influenza vaccination reduces hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Vaccine. 2014;32(30):3843–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.064.

Hung IF, Leung AY, Chu DW, Leung D, Cheung T, Chan CK, et al. Prevention of acute myocardial infarction and stroke among elderly persons by dual pneumococcal and influenza vaccination: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(9):1007–16. https://doi.org/10.1086/656587.

Esme M, Topeli A, Yavuz BB, Akova M. Infections in the elderly critically-ill patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2019.00118.

Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Nagel MA, Gilden D. Risk of stroke and myocardial infarction after herpes zoster in older adults in a US community population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(1):33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.09.015.

Kwon SU, Yun SC, Kim MC, Kim BJ, Lee SH, Lee SO, et al. Risk of stroke and transient ischaemic attack after herpes zoster. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(6):542–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.03.003.

Patterson BJ, Rausch DA, Irwin DE, Liang M, Yan S, Yawn BP. Analysis of vascular event risk after herpes zoster from 2007 to 2014 US insurance claims data. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(5):763–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.12.025.

Kim SY, Oh DJ, Choi HG. Asthma increases the risk of herpes zoster: a nested case-control study using a national sample cohort. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2020;16:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-020-00453-x.

Jillella DV, Wisco DR. Infectious causes of stroke. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019;32(3):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000547.

Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, et al. Human papillomavirus and related diseases in India. Summary report 17 June 2019. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/IND.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2020.

Malkud S, Dyavannanavar V, Purnachandra, Satyanarayana Murthy K. Clinical and morphological characteristics of herpes zoster: a study from tertiary care centre. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2016;26(3):219–22.

Baghel N, Awasthi S, Kumar S. Epidemiological study of herpes zoster in a tertiary care hospital [herpes zoster, HIV seropositivity, post herpetic neuralgia, trigeminal nerve]. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;4550–3. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20174594.

Adhicari D, Agarwal DA. Hospital-based clinical study of herpes zoster: a report of 113 cases. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2017;16:33–8. https://doi.org/10.9790/0853-1601093338.

Vora RV, Singhal RR, Anjaneyan G, Patel T. Clinicoepidemiological study of herpes zoster at rural based tertiary center of Gujarat. IP Indian J Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;4(1):40–3. https://doi.org/10.18231/.2018.0009.

Sharma R, Sharma R. Clinical study of herpes zoster in 109 patients in central referral hospital, Gangtok. Int J Res Dermatol. 2019;5:849–52. https://doi.org/10.18203/issn.2455-4529.

Narayan VV, Iuliano AD, Roguski K, Bhardwaj R, Chadha M, Saha S, et al. Burden of influenza-associated respiratory and circulatory mortality in India, 2010–2013. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):010402. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010402.

Swaminathan S, Mathai D. Protocols for pneumococcal vaccination. J Assoc Phys India. 2016;64. https://www.japi.org/u2b4e434/protocols-for-pneumococcal-vaccination.

Koul PA, Chaudhari S, Chokhani R, Christopher D, Dhar R, Doshi K, et al. Pneumococcal disease burden from an Indian perspective: need for its prevention in pulmonology practice. Lung India. 2019;36(3):216–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_497_18.

World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Regional framework on healthy ageing 2018–2022. 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311067. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Xu W, Wong G, Hwang YY, Larbi A. The untwining of immunosenescence and aging. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(5):559–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-020-00824-x.

Doherty TM, Connolly MP, Del Giudice G, Flamaing J, Goronzy JJ, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, et al. Vaccination programs for older adults in an era of demographic change. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(3):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0040-8.

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463. Accessed 3 July 2020.

Himanshu H, Arokiasamy P, Talukdar B. Illustrative effects of social capital on health and quality of life among older adult in India: results from WHO-SAGE India. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;82:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.01.005.

Simon AK, Hollander GA, McMichael A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc Biol Sci. 1821;2015(282):20143085. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.3085.

Pietrobon AJ, Teixeira FME, Sato MN. Immunosenescence and inflammaging: risk factors of severe COVID-19 in older people. Front Immunol. 2020;11:579220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.579220.

Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039.

Fulop T, Dupuis G, Witkowski JM, Larbi A. The role of immunosenescence in the development of age-related diseases. Rev Invest Clin. 2016;68(2):84–91.

van Twillert I, Han WG, van Els CA. Waning and aging of cellular immunity to Bordetella pertussis. Pathog Dis. 2015;73(8):ftv071. https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftv071.

McElhaney JE, Verschoor CP, Andrew MK, Haynes L, Kuchel GA, Pawelec G. The immune response to influenza in older humans: beyond immune senescence. Immun Ageing. 2020;17:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-020-00181-1.

Del Giudice G, Goronzy JJ, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Lambert PH, Mrkvan T, Stoddard JJ, et al. Fighting against a protean enemy: immunosenescence, vaccines, and healthy aging. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2018;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-017-0020-0.

Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, et al. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02247.

WHO. WHO recommendations for routine immunization: summary tables. https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/Immunization_routine_table1.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 July 2020.

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunization schedules for adults. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult.html#table-age. Accessed 11 July 2020.

Geriatric Society of India. Indian recommendations for vaccination in older adults. 2015. https://www.geriatricindia.com/indian_vaccination_guidelines.html. Accessed 3 July 2020.

Expert Group of the Association of Physicians of India on Adult Immunization in India. Executive summary: the Association of Physicians of India evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on adult immunization. JAPI. 2009;57(API Guidelines).

Rice HR, Varkey P. What immunizations should I offer to my patients? A primer on adult immunizations. JAPI. 2011;59:568–72.

Muruganathan A, Santanu Guha S, Munjal YP, Agarwal SS, Parikh KK, Jha V, et al. Recommendations for vaccination against seasonal influenza in adult high risk groups: South Asian recommendations. JAPI. 2016;64(Special Issue).

Ramasubramanian V. Chapter 6. Adult immunization in India. http://apiindia.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/progress_in_medicine_2017/mu_06.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2020.

Indian Medical Association. Life course immunization 2018. https://ima-india.org/ima/pdfdata/IMA_LifeCourse_Immunization_Guide_2018_DEC21.pdf and https://ima-india.org/ima/pdfdata/Immunization_Schedule_CHART.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Koul PA, Swaminathan S, Rajgopal T, Ramsubramanian V, Joseph B, Shanbhag S, et al. Adult immunization in occupational settings: a consensus of Indian experts. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2020;24(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_50_20.

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. National vaccine policy. 2011. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/immunization/Guidelines/National_Vaccine_Policy.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Gurnani V, Haldar P, Aggarwal MK, Das MK, Chauhan A, Murray J, et al. Improving vaccination coverage in India: lessons from Intensified Mission Indradhanush, a cross-sectoral systems strengthening strategy. BMJ. 2018;363:k4782. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4782.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Roadmap for achieving 90% full immunization coverage in India: a guidance document for the states. 2019. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/Guildelines_for_immunization/Roadmap_document_for_90%25_FIC.pdf and https://www.nhp.gov.in/mission-indradhanush_pg and https://imi2.nhp.gov.in/. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Badur S, Ota M, Ozturk S, Adegbola R, Dutta A. Vaccine confidence: the keys to restoring trust. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(5):1007–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1740559.

Indian Association of Occupational Health (IAOH). Guidebook on adult immunization in occupational health settings. Healthy worker: key to productivity and sustainability 2020. http://occuconindia.com/img/iaoh_book.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2020.

Esposito S, Bonanni P, Maggi S, Tan L, Ansaldi F, Lopalco PL, et al. Recommended immunization schedules for adults: clinical practice guidelines by the Escmid Vaccine Study Group (EVASG), European Geriatric Medicine Society (EUGMS) and the World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(7):1777–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1150396.

Shen AK, Groom AV, Leach DL, Bridges CB, Tsai AY, Tan L. A pathway to developing and testing quality measures aimed at improving adult vaccination rates in the United States. Vaccine. 2019;37(10):1277–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.044.

WHO. Immunization in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. UNICEF and WHO, 16 April 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1275303/retrieve. Accessed 11 July 2020.

NHS. NHS vaccination schedule: adults. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/nhs-vaccinations-and-when-to-have-them/. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) at the Robert Koch Institute: 2017/2018. Epidemiologisches Bulletin. No. 34. 24 Aug 2017.

Siedler A, Koch J, Garbe E, Hengel H, vonKries R, Ledig T, et al. Background paper to the decision to recommend the vaccination with the inactivated herpes zoster subunit vaccine. Statement of the German Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) at the Robert Koch Institute. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2019;62:352–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02882-5.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination and design support for the digital illustrations, on behalf of GSK. Benjamin Lemaire coordinated publication development and editorial support. Athanasia Benekou provided medical writing support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this literature review, including all costs associated with the development and publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

Agam Vora has no financial and non-financial relationships and activities and no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. Alberta Di Pasquale and Shafi Kolhapure are employees of the GSK group of companies, hold shares in the GSK group of companies, and declare no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities and no other conflicts of interest. Ashish Agrawal is an employee of the GSK group of companies and declares no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities and no other conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis, and interpretation of the study, and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vora, A., Di Pasquale, A., Kolhapure, S. et al. Vaccination in Older Adults: An Underutilized Opportunity to Promote Healthy Aging in India. Drugs Aging 38, 469–479 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00864-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00864-4