Abstract

Economic evaluations have increasingly sought to understand how funding decisions within care sectors impact health inequalities. However, there is a disconnect between the methods used by researchers (e.g., within universities) and analysts (e.g., within publicly funded commissioning agencies), compared to evidence needs of decision makers in regard to how health inequalities are accounted for and presented. Our objective is to explore how health inequality is defined and quantified in different contexts. We focus on how specific approaches have developed, what similarities and differences have emerged, and consider how disconnects can be bridged. We explore existing methodological research regarding the incorporation of inequality considerations into economic evaluation in order to understand current best practice. In parallel, we explore how localised decision makers incorporate inequality considerations into their commissioning processes. We use the English care setting as a case study, from which we make inference as how local commissioning has evolved internationally. We summarise the recent development of distributional cost-effectiveness analysis in the economic evaluation literature: a method that makes explicit the trade-off between efficiency and equity. In the parallel decision-making setting, while the alleviation of health inequality is regularly the focus of remits, few details have been formalised regarding its definition or quantification. While data development has facilitated the reporting and comparison of metrics of inequality to inform commissioning decisions, these tend to focus on measures of care utilisation and behaviour rather than measures of health. While both researchers and publicly funded commissioning agencies are increasingly putting the identification of health inequalities at the core of their actions, little consideration has been given to ensuring that they are approaching the problem in a consistent way. The extent to which researchers and commissioning agencies can collaborate on best practice has important implications for how successful policy is in addressing health inequalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Extensive methodological developments have occurred regarding the incorporation of equality considerations into cost-effectiveness analysis. |

The approach has not been developed with the needs or reality (neither political or data) of the local decision makers who control the majority of health and social care funding in England. |

This manuscript interrogates the differences between the two disciplines and seeks to identify a path forward. |

1 Introduction

The burden of inequalities in health are as internationally ubiquitous as they are nebulous in scope and definition. From a global perspective, inequality in health and access to care underpin the majority of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Sustainable Development Goals [1]. While the 17 targets set out in the WHO’s goal to ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ would be considered a minimum standard of care in most high-income countries, they grapple with health inequality nonetheless, with the achievement of this minimum standard not a guarantee of health equity within a nation. While every nation has a unique history of how their healthcare provision has emerged over time, and the scale and type of health inequality within that country varying, pertinent health inequality challenges exist in all settings.

Central to the attempts by decision makers around the world to reduce health inequalities has been the question of where the level of action should lie between national and local agencies, how associated agencies should function, and how to maximise total health while minimising inequality [2]. The underlying trade-off being characterised as one where centralised agencies may be able to achieve greater efficiency by reducing replication of roles, but a decentralised one may be able to be more attuned and responsive to local needs [3].

In parallel to its public policy relevance, there has been a recent expansion in health and care research attempts to incorporate the impact of commissioning decisions on health inequality alongside the traditional focus of total population health [4]. This development has been motivated by two complementary factors: firstly, the recognition that existing, internationally applied, methods of cost-effectiveness analysis fail to facilitate the consistent consideration of health maximisation relative to inequality minimisation [5]. Second, the observation that assessment approaches taken by national health technology assessment agencies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England, resulted in recommendations which implied overall population health improvement, but at the detriment of worsening health inequality [6].

Our aim is to understand the methodological research that has been conducted for incorporating health inequality considerations into economic evaluations (i.e., the ‘researcher-led approach’), and to explore how this compares to existing approaches that have evolved within publicly funded commissioning agencies (i.e., the ‘commissioner-led approach’, where ‘commissioner’ is used in a broad sense to encompass the associated analysts and decision makers).

First, we explore the current state of play on how researcher-led approaches have sought to account for inequality alongside the traditional aim to maximise population health [7]. Second, we consider the commissioner-led approach: specifically, how local commissioners have interpreted and acted on inequalities. To facilitate a clear understanding of how these approaches compare we conducted a detailed exploration of the English setting, later reflecting on the generalisability to other national settings. Finally, we deliberate on how well the two approaches integrate, data available or required to facilitate the approaches, and potential steps to minimise any disconnect when it comes to quantifying and tackling health inequalities. This research was stimulated and informed by workshop discussions between researchers and commissioners as part of a project exploring the potential for “Unlocking data to inform public health policy and practice” [8].

2 Defining Inequality and the Context of Inequality in Health

For descriptive purposes, we define ‘health inequality’ as any difference in individual or group health profiles that can be quantified in a meaningful way, e.g., variation in care service use or access, healthcare needs, or their lived health experience. We consider inequality to have relevance both in terms of geographic variations (e.g., regional commissioning jurisdictions) and population sub-groups (e.g., ethnicities). For the purposes of this paper, we additionally consider health inequality to be relevant to both differences in the stock of health (outcomes such as life expectancy) and access to health care resulting from variations in supply (e.g., the number of GPs in an area), as discussed below this is consistent with the approach often taken in commissioning settings. While an interest in health inequalities is motivated by judgements that are inherently normative, we do not explore the issues regarding the normative or objective nature of inequality, which are explored elsewhere [9,10,11].

3 Setting the Scene: The English Context

In England, equal access to tax-funded healthcare was one of the founding principles of the National Health Service (NHS) during the 1940s [12, 13]. However, whilst this principle has been largely preserved for over 70 years [14], eliminating differences in population subgroups’ health remains elusive. For example, there is a 7.6-year life expectancy gap between women, and 9.4 years for men, in the least and most deprived areas of England [15]. As is true to a varying extent internationally, health inequality in England persists despite a long-running objective of successive governments being its reduction, with a succession of national reports and strategies—the 1980 Black Report [16], the 1998 Acheson Report [17], New Labour’s Health Inequalities Strategy [18], the 2010 Marmot Review [19] and its 10-year reassessment [20]—on the topic.

In England, a plethora of commissioning and administrative structures have been created and re-created with inequality reduction routinely at the heart of their policy mandates in response to these national reports and other stimuli [21]. Related to the NHS, the current shift is towards Integrated Care Systems (ICS), with ICSs having ‘improving outcomes and addressing inequalities’ as a key tenet of their formation [22]. In comparison, Local Authorities (LAs) are responsible for commissioning publicly-funded social care and, since 2013, some public health services. We focus on local commissioners given that the majority of current and planned commissioning responsibility related to health in England can be attributed to LAs (e.g., City Councils), Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), and (from 2022) ICSs. We provide brief details of the role of each in the English healthcare system in Sect. 5, but additional details are available elsewhere [23, 24].

4 The Researcher-Led Approach to Health Inequalities

One innovation developed and refined by health economists in recent decades has been the creation and application of a methodological framework with which to assess care interventions covering a diverse range of health-related factors (e.g., illness, acute and chronic conditions, adverse health events) using an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) approach. In brief, this approach assesses competing interventions by their incremental impact on some measure of health-related outcome, most commonly quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs, a metric capturing both quality and quantity of life), relative to the incremental costs (usually only those borne by the care system), with the ratio of incremental costs and incremental QALYs being termed the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). In a budget-constrained care system, this ICER is conventionally compared to some threshold value—representing the maximum ICER at which decision-makers will fund a new intervention—in order to assess cost-effectiveness. Where the aim is to ensure each individual decision increases population health, this threshold should represent the cost-effectiveness of existing interventions that are candidates for defunding in the case of acceptance of this new intervention [25]. However, in practice the threshold value often reflects a wider set of considerations than the cost-effectiveness of what may be defunded [26].

Fundamental to traditional CEA application is the notion that ‘a QALY is a QALY is a QALY’ [27]. This represents the idea that a QALY is equivalent, comparable, and transferable in the determination of cost-effectiveness irrespective of who gains or loses, with the primary aim being population health maximisation as measured by the QALY. However, this approach has been argued to ignore the trade-offs that are made between overall population health and health equality [28]. By overlooking such occurrences, including the opportunity cost of disinvestment falling inequitably and differential uptake of common healthcare interventions [29], CEA recommendations risk running contrary to the dual-aim of many healthcare decision makers [30]. This lack of explicit consideration of interventions’ inequality impact occurs in many health technology assessment (HTA) processes internationally [31].

In the case of NICE in England, their current reference guide for conducting economic evaluations states: “An additional QALY has the same weight regardless of the other characteristics of the people receiving the health benefit” [32].Footnote 1 This is perhaps in conflict with their stated aim “to reduce health inequalities” [34], alongside an acknowledgement of the body’s legal responsibilities in this regard, and a note that the institute “[takes] into account inequalities arising from socioeconomic factors and the circumstances of certain groups” [35]. While the extent to which any trade-off between equity and population health is currently considered in deliberations is at most limited, research has shown that HTA recommendations made by NICE have had quantifiable impacts on the distribution of health [36], with further research identifying that more deprived groups also bear more of the health loss burden when funding is redistributed [29]. However, in recent years there has been an increasing trend in research to explicitly reflect the trade-off between total health and inequality [4, 37].

In this section we briefly review some of the methods by which inequality has been considered in the researcher-led economic evaluation literature and explore some of the emerging methods in detail to determine their level of consistency with the commissioner-led approach.

4.1 Methods to Reflect Inequality Alongside Cost-Effectiveness

Analytical methods to account for inequality concerns alongside CEA can generally be grouped into equity impact or equity weighting approaches [4]. Avanceña and Prosser’s systematic review of CEAs incorporating equality considerations identified 54 studies, with most published since 2015. The majority were found to take an equity impact approach (n = 46), with five conducting both, and three equity weighting alone [4].

Equity impact analysis produces summaries of cost-effectiveness stratified by the sub-groups of interest, then reports the respective costs and health outcomes for each stratified group alongside the headline summaries of intervention cost-effectiveness for the full population. Although useful when demonstrating the potential subgroup’s inequitable gains and losses, the approach does not incorporate inference of the acceptability of any health and inequality trade-off as no socially acceptable weighting is applied to the potentially competing outcomes.

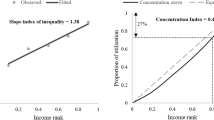

In contrast, equity weighting methods explicitly incorporate differential QALY weighting, allowing for informative analysis as to any trade-off between total population health and inequality. Details of CEA methods incorporating equity weighting, often called distributional CEA (DCEA), and associated tutorials are published [38]. In brief, as with equity impact analysis, the approach involves CEA stratified by relevant subgroups, but with the additional step of allocating a set of weightings to the QALY impact by subgroup. This facilitates the estimation of incremental cost-effectiveness dependent on the weighting set applied to inequality impact versus total population gain. Inevitably the choice of weightings is a key challenge for DCEA as there is currently no routinely accepted set of weightings [28]. In practice, DCEA results are presented using a distribution of weights, so that society’s aversion to inequality is directly compared against the total population QALY gains they would be willing to forgo to minimise inequality. In addition to the challenge of identifying an appropriate estimate of society’s inequality aversion, there is currently no standard weighting approach; Avanceña and Prosser’s review noted that eight identified equity weighting studies each took a different weighting approach [4].

Across both approaches, an additional challenge of incorporating equality concerns into CEA is determining how to categorise the groups of interest. Avanceña and Prosser found “at least 11 different equity criteria have been used” (p. 136), commonly stratified by socioeconomic status (n = 28) or race/ethnicity (n = 16) [4]. Distributional CEA tutorials recommend categorising by index of multiple deprivation (IMD) equity groups, although any grouping for which society’s view of inequality aversion has been quantifiably weighted can be used. While this variation in group categorisation represents a challenge for cross-comparability, the flexibility to the decision maker’s needs is an important benefit when incorporating equity. Distributional CEA does not seek to provide “an algorithmic approach to replace context-specific deliberation with a universal equity formula. Rather, it can be used as an input into context-specific deliberation by decision makers and stakeholders” (p. 119) [39].

In addition to the methods with which to implement the inclusion of inequality considerations, checklists to guide economic evaluations seeking to incorporate inequality considerations have been developed, e.g., the Equity Checklist for Health Technology Assessment [31].

5 The Meaning and Role of Inequality to Local Commissioners

Here we explore the definition and application of health inequality terminology using the setting of English local commissioning as a case study, exploring LAs’, CCGs’, and ICSs’ mandated duty or obligation to consider or act upon inequalities in their commissioning decisions, their potential resources for quantifying their jurisdiction’s inequality levels, each described alongside some examples for discussion purposes. Although we focus on English commissioners, the use of local commissioners to tackle regional health challenges, such as care access and inequality in health considerations, is common internationally, although these organisations may be named differently, with varying degrees of responsibility and geographic scope [2].

5.1 Legal Considerations: The 2010 Equalities Act

Underpinning all UK provision of public services is the 2010 Equalities Act [40], which protects against direct and indirect discrimination across nine characteristics: age, disability, gender, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. Additionally, the Act’s Sect. 1 contains a “socio-economic duty” to consider broader inequalities within a commissioner’s jurisdiction: they must “have due regard to the desirability of exercising (their functions) in a way that is designed to reduce the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage” [40].

However, while the 2010 Equalities Act was enshrined in law, Sect. 1 was not a legal requirement until 2018 in Scotland and 2021 in Wales; but currently (as of April 2022) it is still not a legal requirement in England. As a result, public agencies in England may choose if and how to consider inequality in their decisions. While some have acted on Sect. 1 [41], they are not legally required to beyond the nine protected characteristics: this permits significant variation in the actions taken depending on whether or not the authorities have chosen to take the socio-economic duty upon themselves [41].

5.2 Local Authorities (LAs)

Since the Health and Social Care Act 2012 [42], LAs have had a remit to deliver public health services in addition to their traditional remit, which covers social determinants of health (e.g., housing, education, social care, and transportation); thus, a LA’s inequality remit goes beyond the provision of care services [43, 44]. Here we focus on LAs’ public health responsibilities associated with the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and elements of the Public Health Profiles commissioning indicators provided by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) [45].

Despite LAs’ public health remit, there is little legal requirement or good practice guidance to facilitate their attempts to alleviate health inequality. Publications such as the Local Government Organisation 2018 report ‘A matter of justice: Local government’s role in tackling health inequalities’ [44] speaks to this, with a large emphasis of the burden of inequalities and potential solutions that fall within LA remit, but nothing on the associated legal requirements. Relatedly, and beyond Sect. 1 (whether legally enshrined or not), LAs may be seen as having a moral obligation to address inequality in their respective geographical areas and associated funding structures: council tax, business rates, and government grants. While LAs in poorer areas inevitably have lower revenues through council tax and business rates, these are supported to some extent by government grants, resulting in higher levels of total revenue than richer LAs [46]. However, since 2008 poorer LAs have lost a higher proportion of funding, associated with a corresponding reduction in relative life expectancy [47].

Local authorities’ variation in actioned responsibility to reduce inequalities in their populations was demonstrated in Just Fair’s 2018 report detailing quantitative interviews and analyses with seven LAs [41]. At the time of interview, they found that only one of the seven had embedded the requirements of Sect. 1 into their decision making, doing so voluntarily, with the remaining six pursuing a range of policies seeking to alleviate socio-economic disadvantage but not to the same extent.

Vital to all discussions about reducing inequality is the ability to assess the impact of any action or inaction with robust evidence, with Just Fair identifying aspects associated with data as two of their five essential features: ‘meaningful data assessment’ and ‘using data effectively’ [41]. While it is not possible to be conclusive as to how each LA uses data (e.g., social or health care data) to inform the assessment of inequality at an inter- or intra-authority level, Public Health England's Public Health Profiles, provide valuable insight [45]. This platform gives absolute and relative estimates for a wide range of health indicators and determinants of health. While these are valuable for informing inter- and intra-authority comparisons, as the majority of estimates provide a single estimate for each authority—e.g., prevalence of obesity—they are of little value when seeking to address intra-authority inequality. The exception to this within the Public Health Profiles system is the Health Inequalities Dashboard [48], which provides estimates of relative and absolute gaps within an authority for a number of inequality indicators—both health and its determinants. However, to our knowledge, informed by a review of the relevant literature on the use of data by local governments [49], it is not currently recorded how, or if, LAs use the data in their commissioning decisions.

5.3 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)

The reduction of inequalities in the access to and outcomes from healthcare interventions has been part of CCGs’ remit since their formation under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Each CCG must: “(a) reduce inequalities between patients with respect to their ability to access health services, and (b) reduce inequalities between patients with respect to the outcomes achieved for them by the provision of health services” [42].

This is reflected in CCG funding allocations from NHS England. While the allocation formula has changed over time, specifically in w met and unmet needs are reflected, inequality has always played a part in these allocations [50]. Since 2019/20, funding allocations include adjustments that reflect the relative standardised mortality ratio of those aged ≤ 75 years in the CCG’s region, with the associated proportion of funding allocated on this basis being: primary care, 15%; CCG commissioned services, 10%; speciality services, 5% [51].

In addition to its role in their funding, inequality is also considered in the Oversight and Assessment process, under which NHS England conducts a statutory annual assessment of each CCG. The Oversight Framework that informs the process combines aspects of ‘preventing ill health and reducing inequalities’ [52], recording data on:

-

Maternal smoking at delivery

-

Percentage of children aged 10–11 classified as overweight or obese

-

Injuries from falls in people aged 65+ years

-

Antimicrobial resistance: appropriate prescribing of antibiotics in primary care

-

Proportion of people on GP severe mental illness register receiving physical health checks

-

Inequality in unplanned hospitalisation for chronic ambulatory and urgent care sensitive conditions

Where inequality is considered in the Oversight Framework, it is typically presented in terms of absolute inequality gradient calculated for each CCG. Importantly, these estimates are not used as a blunt measure to assess the CCG’s performance but to provide ‘a focal point for joint work, support and dialogue’ between the various stakeholders [53].

5.4 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs)

Integrated Care Systems will become statutory bodies in 2022, taking over the commissioning function currently held by CCGs and with their modus operandi ‘improving outcomes and addressing inequalities’ [22]. Underpinning this aim is the hypothesis that improved integration of services both within healthcare and between sectors represents a better approach than the more competitive process of service commissioning that underpinned CCG functioning. Local authorities and ICSs will have a duty to collaborate, replacing current collaboration processes, which may have previously existed between LAs and CCGs. Additionally, ICSs will shift to ‘place-based working’, focussing on individual geographic localities, the needs of their populations, and existing partnerships. As such, integration is likely to be interpreted and operationalised differently across ICSs that will inevitably vary in these elements.

At the time of writing, the details as how the modus operandi will be operationalised by the ICSs and monitored by NHS England are limited to the high-level aims outlined in the White Paper [22], with the expectation that each ICS will have significant flexibility in deciding their path forward. However, the increased focus on local needs and solutions suggests ICS decision-making is likely to shift further towards approaches that are tailored to local systems, e.g., inequality measures selected to address known local issues such as smoking cessation. Secondly, the pragmatic approach to monitoring inequality levels by NHS England for CCGs may well continue for ICSs, with the limited reporting of inequality measures (see Sect. 5.3) continuing to inform dialogue between NHS England and ICSs.

Overall, this suggests that a two-level approach to inequality might continue to emerge: one level focussing on inter-ICS comparisons to inform the funding allocation, and one level within each ICS that is specific to the needs and challenges faced locally. This risks producing potentially inconsistent pressures within each ICS as they attempt to grapple with the health and inequality considerations that are specific to their jurisdictions as well as broader inequality measures for comparisons with other ICSs [54].

6 Generalisability of the English Local Commissioning Landscape Internationally

With the diverse nature of care commissioning responsibilities internationally it is not feasible to determine whether the experience in England is directly comparable to other nations. However, it is self-evident that, due to commissioners’ proximity to service provision data, such as patient care records, the most readily available approach to conceptualising and monitor health inequality will always be informed by such data. Furthermore, frameworks the UK’s 2010 Equalities Act are mirrored internationally. Therefore, the experience in England, described in Sect. 5, is expected to be internationally transferable in the pertinent details.

7 Comparing the Two Approaches and Recommendations

To discuss where and how the researcher and commissioner-led approaches can begin to come together and the potential benefits of doing so, it is important to consider their relative practical and methodological strengths and limitations when the goal is to inform localised commissioning. Our suggested considerations are in Table 1.

Building on these strengths and limitations, and the English case-study, we have a number of recommendations to begin to address the disconnect:

-

The time and financial costs involved with the creation of DCEA models implies that it is not feasible for each commissioner to have locally tailored models. Instead, models should be commissioned nationally, or collaboratively across LAs and ICSs, with flexibility to local context, accessibility, and co-development seen as fundamental parts of model development. Such an approach would facilitate research impact from an academic perspective, and better use the skills, knowledge, and data availability of all parties.

-

A common set of agreed vocabulary around the definitions of health inequality, and agreement on how aspects of health inequality are to best quantified, e.g., through minimum data specifications and reporting standards.

-

To address the overall divide in the two disciplines, closer collaboration must be prioritised with a focus on the ease with which the two settings can identify potential research partners and disseminate the latest research.

-

Better reflection and documentation of where existing quantitative frameworks for determining cost-effectiveness may differ from the commissioning reality faced by the commissioners, e.g., finance and policy cycles, ring-fenced budgets, risk aversion to overspend, and diverse outcome measures.

-

Development and maintenance of local and national metadata to provide a clear understanding of who holds what data relevant to healthcare inequality, and how it can be accessed. The supplementary appendix to this paper provides further details of the challenges of identifying and accessing key data regarding pertinent inequality data in the English case study.

-

Make the analysis and reporting of the distributional impact of interventions subjected to CEA as minimum standard, with the conducting of DCEA an expectation where once course of action does not strictly dominate all others.

8 Discussion

We have explored researcher- and commissioner-led approaches to define, quantify, and analyse health inequalities. Based on the English care setting example, the different perspectives and their starting points have resulted in approaches that in many ways share little beyond the use of the term ‘health inequality’; this is likely to be the case internationally. The researcher-led approach, specifically DCEA, puts overall patient health at its centre, in addition to assumptions regarding the ability to categorise patients into their demographic groups, and requires access to an underlying CEA model. In contrast, the commissioner-led approach focusses on available data, relying on the comparative summaries of measures of healthcare utilisation and diagnoses, typically stratified into geographic groupings often based on a commissioner’s jurisdiction. Although, in the English setting the recent White Paper on ‘Levelling Up the United Kingdom’ has underlined aims to better use the Healthy Life Expectancy measure to record inequalities [55]. Availability of data and ability to quantify inequalities will be a challenge internationally, often dependent on the extent to which countries/regions are willing and able to collect the relevant and necessary data.

It would be misleading to suggest there have been no interactions to date between researchers and commissioners to inform these approaches, For example, a report commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care has called for ‘better, broader, and safer’ use of health data for research and analysis [56]. However, there are a number of existing barriers to overcome in order to enable consistency across approaches. Most significantly, these include finding a common set of vocabulary around definitions of health inequality, and agreement on how aspects of health inequality are to be quantified. Research has found that while many decision makers desire a greater level of integration of economic evaluation into the decision-making process, in practice this does not occur because of issues of accessibility [57] and the perceived limited relevance of current frameworks to the reality faced by commissioners [58]. From the commissioner perspective, economic evaluations of care interventions have conventionally focussed on the national decision-making context, assuming local commissioners are able to take on a level of decision uncertainty and fund interventions based on cost-effectiveness rather than affordability [59]. Furthermore, some challenges to the alignment of the approaches are likely to be perpetual, such as commissioners’ requirement to place their legal duty at the heart of any commissioning decision, and the cost of producing economic evaluations such as DCEAs to inform all budget allocation decisions.

9 Conclusion

Developments in economic evaluation methodology, specifically DCEA, have given analysts a means of presenting the cost-effectiveness of care technologies for the whole eligible population alongside the associated impact on health inequality. However, limited consideration has been given to how this approach can be applied at the point where health inequalities are most relevant and arguably best addressed, often at a local commissioner level. Additionally, lessons need to be learnt in the researcher-led world for such approaches to have greater relevance and impact, and consideration needs to be given to the data used to quantify and evaluate aspects of health inequality within different contexts. Ultimately, it is important that researchers and commissioners are consistent in their approach to defining, quantifying, and analysing health inequalities if the repeated aim of reducing health inequalities is to be achieved.

Notes

Despite this statement, additional weight was previously given to QALYs gained subject to meeting ‘end-of-life’ criteria [33]. The recent methods review has seen a shift away from this approach to instead focusing on the level of severity of health burden of beneficiaries, which could, in principle, be consistent with the aim to reduce health inequalities—particularly if consideration is taken of the distribution of opportunity costs. In practice, this can be achieved by using a method that we discuss in the next section: distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA).

References

World Health Organization. The sustainable development goals report. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

World Health Organization. The role of local government in health: comparative experiences and major issues. Geneva: WHO; 1997.

Peckham SEM, Powell M, Greener I. Decentralisation, centralisation and devolution in publicly funded health services: decentralisation as an organisational model for health-care in England. In: Technical Report. London: LSHTM; 2005.

Avanceña AL, Prosser LA. Examining equity effects of health interventions in cost-effectiveness analysis: a systematic review. Value Health. 2021;24(1):136–43.

Cookson R, et al. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to address health equity concerns. Value Health. 2017;20(2):206–12.

Griffin S, et al. Evaluation of intervention impact on health inequality for resource allocation. Med Decis Mak. 2019;39(3):171–82.

Drummond MF, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Franklin M. Unlocking real-world data to promote and protect health and prevent ill-health in the Yorkshire and Humber region. https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.14723685.v1. 2021.

Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27106–27106.

Global Health Europe. Inequity and inequality in Health. 2009. [accessed 10/12/2021]. Available from: https://globalhealtheurope.org/values/inequity-and-inequality-in-health/.

Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–45.

National Health Service Bill, in 9&10 Geo. 6, CH81. 1946.

Delamothe T. NHS at 60: founding principles. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2008;336(7655):1216–8.

Department of Health & Social Care. The NHS constitution for England. London: DHSC; 2021.

Office for National Statistics. Health state life expectancies by national deprivation deciles, England: 2017 to 2019. Newport: ONS; 2021.

Department of Health Social Security. Working Group on Inequalities in Health, Inequalities in health: report of a research working group. HM Stationery Office; 1980.

Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health report. In: Department of Health and Social Care. London: DHSC; 2001.

House of Commons Health Committee. Health inequalities: third report of session 2008–09. London: The Stationery Office; 2009.

Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health. 2012;126:S4–10.

Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. 2020;368:m693.

Turner D, et al. Prospects for progress on health inequalities in England in the post-primary care trust era: professional views on challenges, risks and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):274.

Department of Health & Social Care. Working together to improve health and social care for all. London: DHSC; 2021.

Charles, A. Integrated care systems explained: making sense of systems, places and neighbourhoods. 2021. [cited accessed: 13/04/2022]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained.

Humphries R. The NHS, local authorities and the long-term plan: in it together? 2019. [cited accessed: 13/04/2022]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2019/03/nhs-local-authorities-long-term-plan.

Culyer AJ. Cost-effectiveness thresholds in health care: a bookshelf guide to their meaning and use. Health Econ Policy Law. 2016;11(4):415–32.

Dillon A. Carrying NICE over the threshold. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/news/blog/carrying-nice-over-the-threshold. Accessed 21 June 2022.

Weinstein MC. A QALY is a QALY is a QALY—or is it? J Health Econ. 1988;7(3):289–90.

Cookson R, et al. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis: quantifying health equity impacts and trade-offs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020.

Love-Koh J, et al. Estimating social variation in the health effects of changes in health care expenditure. Med Decis Mak. 2020;40(2):170–82.

Avanceña ALV, Prosser LA. Innovations in cost-effectiveness analysis that advance equity can expand its use in health policy. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(2): e008140.

Benkhalti M, et al. Development of a checklist to guide equity considerations in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021;37:e17.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The guidelines manual. London: NICE; 2012.

Collins M, Latimer N. NICE’s end of life decision making scheme: impact on population health. BMJ Br Med J. 2013;346: f1363.

NICE. Our principles: the principles that guide the development of NICE guidance and standards. [cited 2022 21st Janaury]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/who-we-are/our-principles.

Charlton V. Justice, transparency and the guiding principles of the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Health Care Anal. 2021;30:115–45.

Love-Koh J, et al. Aggregate distributional cost-effectiveness analysis of health technologies. Value Health. 2019;22(5):518–26.

Ward T, et al. Incorporating equity concerns in cost-effectiveness analyses: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(1):45–64.

Asaria M, Griffin S, Cookson R. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis: a tutorial. Med Decis Mak. 2016;36(1):8–19.

Cookson R, et al. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis comes of age. Value Health. 2021;24(1):118.

Government Equalities Office. Equality Act 2010: guidance. London: GEO; 2013.

Fair J. Tackling socio-economic inequality locally. London: Just Fair; 2018.

Department of Health & Social Care. Health and social care act 2012. London: DHSC; 2012.

Department of Health & Social Care. The new public health role of local authorities. London: DHSC; 2012.

Local Government Association. A matter of justice: local government’s role in tackling health inequalities. London: LGA; 2018.

Public Health England. Public health profiles. 2021. [Accessed 15/9/2021]. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk.

Institute for Fiscal Studies. English local government funding: trends and challenges in 2019 and beyond. London: IFS; 2019.

Alexiou A, et al. Local government funding and life expectancy in England: a longitudinal ecological study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(9):e641–7.

Public Health England. Health inequalities dashboard. 2021. Acessed 10/12/2021.

Clowes M, Sutton A. “It’s A Grey Area”: searching the grey literature on how local governments use real-world data. Sheffield: The University of Sheffield; 2021.

Buck D, Dixon A. Improving the allocation of health resources in England. London: Kings Fund; 2013.

England NHS. Note on Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) allocations 2019/20–2023/24. London: NHS England; 2019.

England NHS, Improvement NHS. NHS oversight framework 2019/20: CCG metrics technical annex. London: NHS England; 2019.

England NHS. NHS oversight framework for 2019/20. London: NHS England; 2019.

Charles A, Ewbank L, Naylor C, Walsh N, Murray R. Developing place-based partnerships: the foundation of effective integrated care systems. London: Kings Fund; 2021.

HM Government. Levelling up the United Kingdom: white paper. London: HM Government; 2022.

Department of Health and Social Care. Better, broader, safer: using health data for research and analysis. London: DHSC; 2022.

Frew E, Breheny K. Health economics methods for public health resource allocation: a qualitative interview study of decision makers from an English local authority. Health Econ Policy Law. 2020;15(1):128–40.

Hinde S, et al. The relevant perspective of economic evaluations informing local decision makers: an exploration in weight loss services. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(3):351–6.

Lomas J, et al. Resolving the “Cost-Effective but Unaffordable” paradox: estimating the health opportunity costs of nonmarginal budget impacts. Value Health. 2018;21(3):266–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: William Whittaker, Steven Senior, Katherine Brown, Gerry Richardson, Thomas Clarke, Tony Stone, and Suzanne Mason for their valuable contributions to the many different stages of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme (NIHR award identifier: 133634) with in kind support provided by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Yorkshire and Humber (ARC-YH; NIHR award identifier: 200166). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

No authors have any conflicts of completing interests to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

SH, MF, and DH were responsible for the conceptualisation of the research, SH wrote the original draft with review, editing, and additional input from DH, MF, and JL.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hinde, S., Howdon, D., Lomas, J. et al. Health Inequalities: To What Extent are Decision-Makers and Economic Evaluations on the Same Page? An English Case Study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 20, 793–802 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00739-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00739-8