Abstract

With the arrival of an infant, many households face increased demands on resources, changes in the composition of income, and a potentially heightened risk of income inadequacy. Changing household economic circumstances around a birth have implications for child and family well-being, women’s economic security, and public program design, yet have received little research attention in the United States. Using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, this study provides new descriptive evidence of month-to-month changes in household income adequacy and the composition of household income in the year before and after a birth. Results show evidence of significant declines in household income adequacy in the months around a birth, particularly for single mothers who live without other adults. Income from public benefit programs buffers but does not eliminate declines in income adequacy. Results have implications for policies targeted at this period, including public benefit and parental leave programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data used in this article and supporting materials are available at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sipp/data/datasets.html.

Notes

The related relationship between individual and household economic circumstances and fertility has received considerable theoretical and empirical attention (see, e.g., Blau et al. 2010). In this article, I focus not on the fertility decision but on household economic circumstances around a birth, conditional on a live birth.

Although some zero-income observations in survey data are cases of misreporting, many represent households with no income of the types included in the measure (Nichols and Zimmerman 2008). Negative values on income may be related to investment and self-employment income and are more likely among individuals of higher socioeconomic status.

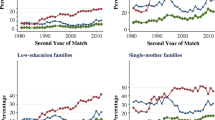

As in Fig. 2, each line in Figs. 4 and 5 represents results from a separate regression, all estimated using Eq. (2). Solid dots indicate statistically significant changes in the share of household income from the given source, relative to the pre-pregnancy level (p < .05). Corresponding full regression results are available from the author by request.

Earlier pre-birth reductions in lower-educated mothers’ earnings contributions along with faster post-birth recovery are both consistent with existing research and are somewhat puzzling to reconcile. Future research should investigate mechanisms that help explain these patterns.

References

Aassve, A., Mazzuco, S., & Mencarini, L. (2005). Childbearing and well-being: A comparative analysis of European welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 15, 283–299.

Angrist, J. D., & Evans, W. (1998). Children and their parents’ labor supply: Evidence from exogenous variation in family size. American Economic Review, 88, 450–477.

Bane, M. J., & Ellwood, D. T. (1986). Slipping into and out of poverty: The dynamics of spells. Journal of Human Resources, 21, 1–23.

Bauman, K. J. (1999). Shifting family definitions: The effect of cohabitation and other nonfamily household relationships on measures of poverty. Demography, 36, 315–325.

Bittman, M., England, P., Sayer, L., Folbre, N., & Matheson, G. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109, 186–214.

Blank, R. M., & Greenberg, M. H. (2008). Improving the measurement of poverty (Hamilton Project Discussion Paper No. 2008–17). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution and The Hamilton Project.

Blau, F. D., Ferber, M. A., & Winkler, A. E. (2010). The economics of women, men and work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bould, S., Crespi, I., & Schmaus, G. (2012). The cost of a child, mother’s employment behavior and economic insecurity in Europe. International Review of Sociology, 22, 5–23.

Brandrup, J. D., & Mance, P. L. (2011). How do pregnancy and newborns affect the household budget? Family Matters, 88, 31–41.

Caceres-Delpiano, J., & Simonsen, M. (2012). The toll of fertility on mothers’ wellbeing. Journal of Health Economics, 31, 752–766.

Charles, M., Buchmann, M., Halebsky, S., Powers, J. M., & Smith, M. M. (2001). The context of women’s market careers. Work and Occupations, 28, 371–396.

Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2014). Boosting family income to promote child development. Future of Children, 24(1), 99–120.

Feenberg, D., & Coutts, E. (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12, 189–194.

Gibson-Davis, C., & Rackin, H. (2014). Marriage or carriage? Trends in union context and birth type by education. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 506–519.

Giles, D. E. (2011). Interpreting dummy variables in semi-logarithmic regression models: Exact distributional results (Econometrics Working Paper EWP1101). Victoria, Canada: University of Victoria, Department of Economics.

Glauber, R. (2007). Marriage and the motherhood wage penalty among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 951–961.

Glauber, R. (2008). Race and gender in families and at work: The fatherhood wage premium. Gender & Society, 22, 8–30.

Han, W.-J., Ruhm, C. J., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2008). The timing of mothers’ employment after childbirth. Monthly Labor Review, 131(6), 15–27.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312, 1900–1902.

Hill, H. D. (2012). Welfare as maternity leave? Exemptions from welfare work requirements and maternal employment. Social Service Review, 86, 37–67.

Hill, H. D., Morris, P. M., Gennetian, L. A., Wolf, S., & Tubbs, C. (2013). The consequences of income instability for children’s well-being. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 85–90.

Kalil, A., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Mothers’ economic conditions and sources of support in fragile families. Future of Children, 20(2), 39–61.

Kennedy, S., & Fitch, C. (2012). Measuring cohabitation and family structure in the United States: Assessing the impact of new data from the Current Population Survey. Demography, 49, 1479–1498.

Killewald, A. (2013). A reconsideration of the fatherhood premium: Marriage, residence, biology, and the wages of fathers. American Sociological Review, 78, 96–116.

LaLumia, S. (2013). The EITC, tax refunds, and unemployment spells. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(2), 188–221.

Laughlin, L. (2011). Maternity leave and employment patterns of first-time mothers: 1961–2008 (Current Population Reports No. P70-128). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.

Lundberg, S., Pollak, R., & Wales, T. J. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. Journal of Human Resources, 32, 463–480.

Lundberg, S., & Rose, E. (2000). Parenthood and the earnings of married men and women. Labour Economics, 7, 689–710.

Lundberg, S., & Rose, E. (2002). The effects of sons and daughters on men’s labor supply and wages. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 251–268.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J. K., Curtin, S. C., & Matthews, T. J. (2015). Birth: Final data for 2013 (National Vital Statistics Reports Vol. 64, No. 1). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System.

McKernan, S.-M., & Ratcliffe, C. (2005). Events that trigger poverty entries and exits. Social Science Quarterly, 86, 1146–1169.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2012). Identifying the disadvantaged: Official poverty, consumption poverty, and the new Supplemental Poverty Measure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 111–136.

Misra, J., Moller, S., Strader, E., & Wemlinger, E. (2012). Family policies, employment and poverty among partnered and single mothers. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30, 113–128.

Nichols, A., & Zimmerman, S. (2008). Measuring trends in income variability. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Paschall, K., & Bartlett, J. D. (2019). Child poverty declines even as disparities persist among the nation’s youngest children. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends.

Sayer, L., & Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Women’s economic independence and the probability of divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 906–943.

Short, K. S. (2014). The supplemental poverty measure: 2013 (Current Population Reports No. P60-251). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & McLanahan, S. (2002). The living arrangements of new unmarried mothers. Demography, 39, 415–433.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2007a). Motherhood and women’s earnings in Anglo-American, continental European, and Nordic countries. Feminist Economics, 13(2), 55–91.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2007b). The incomes of families with children: A cross-national comparison. Journal of European Social Policy, 17, 299–318.

Slack, K. S., Berger, L. M., Kim, B., & Yang, M. Y. (2012). The role of child support in the current economic safety net for low-income families with children (Report No. CSPR-11-12-T11). Madison: University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty.

Stevens, A. H. (2012). Poverty transitions. In P. N. Jefferson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 494–518). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau (2001). Survey of Income and Program Participation users’ guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Wagmiller, R. L., Lennon, M. C., Kuang, L., Alberti, P. M., & Aber, L. (2006). The dynamics of economic disadvantage and children’s life chances. American Sociological Review, 71, 847–866.

Waldfogel, J. (2010). What children need. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Winston, P. (2014). Work-family supports for low-income families: Key research findings and policy trends. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Ybarra, M. (2013). Implications of paid family leave for welfare participants. Social Work Research, 37, 375–387.

Yelowitz, A. (2002). Income variability and WIC eligibility: Evidence from the SIPP (Working paper). Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Working Paper.

Acknowledgments

Analyses of Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data benefited from training supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. SES 1131500. John Hisnanick at the U.S. Census Bureau provided valuable details on the SIPP data. The author also gratefully acknowledges support for this study from the University of California, Davis Center for Poverty Research as well as feedback on earlier versions of this project from Julia Henly, Heather Hill, Hans-Peter Kohler, Susan Lambert, Taryn Morrissey, Harold Pollack, Marci Ybarra, and participants at the Council on Social Work and Education (CSWE), Population Association of America (PAA), Research Conference on Self-Sufficiency (RECS), Society for Social Work and Research (SSWR), and Work and Family Researchers Network (WFRN) conferences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 682 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stanczyk, A.B. The Dynamics of U.S. Household Economic Circumstances Around a Birth. Demography 57, 1271–1296 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00897-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00897-1