Abstract

Primary care-mental health integration (PC-MHI) is growing in popularity. To determine program success, it is essential to know if PC-MHI services are being delivered as intended. The investigation examines responses to the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire (PPAQ) to explore PC-MHI provider practice patterns. Latent class analysis was used to identify clusters of PC-MHI providers based on their self-report of adherence on the PPAQ. Analysis revealed five provider clusters with varying levels of adherence to PC-MHI model components. Across clusters, adherence was typically lowest in relation to collaboration with other primary care staff. Clusters also differed significantly in regard to provider educational background and psychotherapy approach, level of clinic integration, and previous PC-MHI training. The PPAQ can be used to identify PC-MHI provider practice patterns that have relevance for future clinical effectiveness studies, development of provider training, and quality improvement initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization and World Organization of Family Doctors, Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva, Switzerland; 2008.

Bower P, Gilbrody S. Managing common mental health disorders in primary care: conceptual models and evidence base. BMJ. 2005; 330: 839-842.

Szymanski BR, Bohnert KM, Zivin K, McCarthy JF. Integrated care: treatment initiation following positive depression screens. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(3): 346-52.

Felker BL, Barnes RF, Greenberg DM, et al. Preliminary outcomes from an integrated mental health primary care team. Psychiatr Serv. 2004; 55: 442-444.

Ray-Sannerud BN, Dolan DC, Morrow CE, et al. Longitudinal outcomes after brief behavioral health intervention in an integrated primary care clinic. Fam Syst Health. 2012; 30(1): 60-71.

Miller BF, Mendenhall TJ, Malik AD. Integrated primary care: an inclusive three-world view through process metrics and empirical discrimination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009; 16(1): 21-30.

Gatchel RJ, Oordt MS. Clinical health psychology and primary care: practical advice and clinical guidance for successful collaboration. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003.

Martin MP, White MB, Hodgson JL, Lamson AL, Irons TG. Integrated primary care: a systematic review of program characteristics. Fam Syst Health. 2014; 32(1): 101-115.

Johnson-Lawrence V, Zivin K, Szymanski BR, Pfeiffer PN, McCarthy JF. VA Primary Care-Mental Health Integration: patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services 2008–2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2012; 63: 1137-1141.

Tew J, Klaus J, Oslin DW. The Behavioral Health Laboratory: Building a stronger foundation for the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010; 10: 130-145.

Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010; 28: 91-113.

Chang ET, Rose DE, Yano EM, et al. Determinants of readiness for primary care-mental health integration (PC-MHI) in the VA Health Care System. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(3): 353-62.

Pomerantz AS, Sayers SL. Primary care-mental health integration in healthcare in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Fam Syst Health. 2010; 28: 78-82.

Wray LO, Szymanski BR, Kearney LK, McCarthy JF. Implementation of primary care-mental health integration services in the Veterans Health Administration: program activity and associations with engagement in specialty mental health services. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012; 19(1): 105-16.

Johnson-Lawrence V, Szymanski BR, Zivin K, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Pfeiffer PN. Primary care-mental health integration programs in the Veterans Affairs health system serve a different population that specialty mental health clinics. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012; 14: (3).

Carroll C, Patterson M, S. W, Booth B, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007; 2: (40).

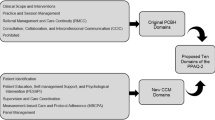

Beehler GP, Funderburk JS, Possemato K, Vair CL. Developing a measure of provider adherence to improve the implementation of behavioral health services in primary care: a Delphi study. Implement Sci. 2013; 8: (19).

Beehler GP, Funderburk JS, Possemato K, Dollar KM. Psychometric assessment of the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire (PPAQ). Transl Behav Med. 2013; 3: 379-3391.

Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010; 5: 67.

Fauth J, Tremblay G.The Integrated Care Evaluation Project. Antioch 2011.

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 14: 2007.

Magidson J, Vermunt JK. Latent class models. In: Kaplan D, ed. The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2004: 175-198.

O’Donohue WT, Cummings NA, Cummings JL. The unmet educational agenda in integrated care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009; 16(1): 94-100.

Blount FA, Miller BF. Addressing the workforce crisis in integrated primary care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009; 16: 113-119.

VHA. Uniform Mental Health Services in the VA Medical Centers and Clinics. 2008 [cited 2014 April 15]; Available from: [online].

Beehler G, Wray L. Behavioral health providers’ perspectives of delivering behavioral health services in primary care: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012; 12: 337.

Knowles P. Collaborative communication between psychologists and primary care providers. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009; 16(1): 72-6.

Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care: Step-by-Step Guidance for Assessment and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Nash JM, McKay KM, Vogel ME, Masters KS. Functional roles and foundational characteristics of psychologists in integrated primary care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012; 19(1): 93-104.

Koenig CJ, Maguen S, Daley A, Cohen G, Seal KH. Passing the baton: a grounded practical theory of handoff communication between multidisciplinary providers in two Department of Veterans Affairs outpatient settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(1): 41-50.

Kauth MR, Sullivan G, Blevins D, et al. Employing external facilitation to implement cognitive behavioral therapy in VA clinics: a pilot study. Implement Sci. 2010; 5: 75.

Cully JA, Teten AL, Benge JF, Sorocco KH, Kauth MR. Multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioral therapy training for the veterans affairs primary care setting. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry.2010; 12:(3).

Mignogna J, Hundt NE, Kauth MR, et al. Implementing brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: a pilot study. Transl Behav Med. 2014; 4: 175-83.

Nederhof AJ. Methods of coping with social desirability bias: a review. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1985; 15: 263-280.

Wandersman A, VH Chien, J Katz. Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement. Am J Community Psychol. 2012.

National Research Council, Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. Washington, DC; 2006.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Center for Integrated Healthcare and the VA Western New York Healthcare System. The information provided in this study does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are known conflicts of interest for reasons financial or otherwise, no known competing interests, and no companies or products are being featured in this research.

Adherence to ethical principles

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the study protocol approved by the VA Western New York Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Implications

Research: Provider groups identified by the PPAQ can be used in future clinical effectiveness studies to determine if provider adherence moderates the effect of integrated care services on patient outcomes.

Policy: Policy makers and administrators can use the PPAQ to characterize the implementation status of integrated care programs by monitoring domains of provider practice.

Practice: Analysis of practice patterns using the PPAQ suggests that integrated care providers can benefit from additional training and quality improvement efforts that target interdisciplinary collaboration and adherence to a brief, time-limited treatment model.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Beehler, G.P., Funderburk, J.S., King, P.R. et al. Using the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire (PPAQ) to identify practice patterns. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 5, 384–392 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0325-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0325-0