Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to evaluate general changes and investigate the association between diet quality, physical activity (PA), and sedentary time (ST) during COVID-19 lockdown and the subsequent 7-month changes in health-related behaviours and lifestyles in older people.

Participants

1092 participants (67–97y) from two Spanish cohorts were included.

Design

Telephone-based questionaries were used to evaluate health-related behaviours and lifestyle. Multinomial logistic regression analyses with diet quality, PA, and ST during lockdown as predictors for health-related behaviours changes post-lockdown were applied.

Results

Diet quality, PA, and ST significantly improved post-lockdown, while physical component score of the SF-12 worsened. Participants with a low diet quality during lockdown had higher worsening of post-lockdown ST and anxiety; whereas those with high diet quality showed less likelihood of remaining abstainers, worsening weight, and improving PA. Lower ST was associated with a higher likelihood of remaining abstainers, and worsening weight and improving social contact; nevertheless, higher ST was linked to improvement in sleep quality. Lower PA was more likely to decrease alcohol consumption, while higher PA showed the opposite. However, PA was more likely to be associated to remain abstainers.

Conclusions

Despite improvements in lifestyle after lockdown, it had health consequences for older people. Particularly, lower ST during lockdown seemed to provide the most medium-term remarkable lifestyle improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (COVID-19) has had profound health, social and economic consequences and has also resulted in a period of home lockdown requiring the sudden disruption of daily activities (1). In Spain, the Government approved this lockdown on March 15th of 2020 (2), being highly restrictive until May 2nd, when the return to the so-called “new normality” began, with a reduction of movement restrictions and the possibility to go outside for exercising or walking among other basic activities (3). This lockdown was essential due to the need for social isolation and distancing to slow the progression of the disease (4); and, while these regulations have contributed to reduce the infection rate, they might also have potentially adverse health effects such as mental health problems (stress, anger, and post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, etc.) (5, 6), and worsening chronic diseases prevalence (7). The main reason potentially underlying this discouraging scenario has been the increased prevalence of health-related behaviours, i.e., low physical activity (PA), increased sedentary time (ST), poor diet quality, sleep disorders or changes in alcohol consumption, which may have led to higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depression (8, 9). In addition to these direct effects of lockdown, the fear of becoming infected with COVID-19 through personal contact must also be taken into account (10), as it could also have increased the disruption of daily activities.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences have affected all population age groups, age is a risk factor in terms of complications and associated mortality (11). Therefore, older people are an especially vulnerable group to lockdown measures (12). Recent population-based longitudinal studies in the older Spanish population have shown an increase in health-related behaviours during the lockdown period, leading to an overall worsening of health (10, 13). In addition, limited access to health services has further aggravated the situation and intensified these potential risks (14). Consequently, these studies can offer important insights into how the pandemic has affected older people, mainly because they presented prepandemic data on individuals’ health and provides an accurate picture of the effect of lockdown (4). Nevertheless, no studies have examined the effects of this lockdown on health-related behaviours and lifestyle throughout the return to the “new normality” in older people. Thus, the present study aimed to 1) evaluate the changes in the lifestyle and health-related behaviours in Spanish older people after emerging from a strict 2-month lockdown and, 2) investigate how the diet quality, PA, and ST during the lockdown was associated with the subsequent changes in health behaviours and lifestyle adaptations during the return to the “new normality”.

Material and methods

Study design and cohorts

This study included two Spanish prospective cohorts to create a new sub-cohort related to COVID-19: The Toledo Study for Healthy Ageing (TSHA) and the Elderly-Exernet Multi-Center Study (EXERNET). TSHA is a prospective study of older people aged ≥65 years from the province of Toledo. This study includes three waves established between 20062009, 2011–2013 and 2015–2017. Likewise, EXERNET is a multi-centre study of non-institutionalized individuals aged ≥65 years recruited in Aragón, Castilla-La Mancha, Madrid, and Cádiz. This study also includes three waves implemented in similar moments: 2008–2009, 2011–2012 and 2016–2017. This new sub-cohort included participants who had been assessed twice, during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain and 7-months later. Thus, the baseline data were collected between April 28th and June 30rd, always asking regarding the lockdown period, while the follow-up data were collected during December 2020.

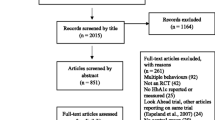

At baseline, a total of 2982 participants were recruited from the TSHA and EXERNET, although only 1788 participants agreed to participate (938 from TSHA and 850 from EXERNET, 63% response rate in total). Thus, 589 participants could not be contacted, and 605 refused to participate. 1247 of them agreed to participate in the follow-up (688 from TSHA and 559 from EXERNET, 70% response rate in total), 217 participants could not be contacted and 324 refused to participate. Finally, 11 participants infected with COVID-19 were excluded and 1092 participants with both evaluations complete (33.5% of women) were finally included in the analyses. Participants gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Toledo Hospital Complex (Protocol #2203/30/2005) for the TSHA and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (#18/2008) for EXERNET.

Procedure

A telephone-based structured interview (45 min) performed by qualified technicians following a standardised protocol was used to obtain data on health behaviours, mental and physical health, and their potential determinants including demographic and social variables at baseline and follow-up.

Predictors

Diet quality, PA and ST were used at baseline (during COVID-19 lockdown) as predictors of changes in health risk factors and lifestyle. Diet quality was assessed using the 14-point Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener Questionnaire (MEDAS), a questionary widely used and validated in older Spanish people (15). The MEDAS comprises 14 questions, where 12 questions are related to food consumption frequency and two questions to food intake habits considered characteristic of the Mediterranean diet. The final score ranges from 0 to 14, allowing to classify participants according to their adherence to the Mediterranean diet into low (MEDAS <5), medium (MEDAS: 5–9) and high (MEDAS >9) (16). PA was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), a specific and validated scale for older people (17). PASE included light activities, such as walking, and moderate or strenuous sports or exercise, which provide a total score calculated by multiplying the amount of time spent on each activity by the respective weights and adding all activities together, a higher score means a higher PA (17). Thus, according to their PA levels, older people were classified into tertiles, with those with the lowest PA being at T1 and those with the highest PA being at T3 (18). ST was determined by total daily ST minutes, which included minutes spent watching TV, using electronic devices, reading, listening to music, napping, and sunbathing. In relation to this, participants were classified into tertiles, with those with lower ST being at T1 and those with higher ST at T3 (18).

Follow-up variables

In this study, we used variables related to health risk factors and lifestyle that might have been affected by the COVID19 lockdown. In particular, we included the changes in alcohol consumption, diet quality (MEDAS), weight, ST, PA (PASE), hours of night-time sleep, sleep quality (classified as “excellent”, “good”, “fair”, “poor” and “very poor”), anxiety (the 12-item General Health Questionary [GHQ-12]), social contact (daily social contact with family or friends and living alone) and quality of life (the 12-item Short Form [SF-12], distinguishing between the physical component summary [PCS] and the mental component summary [MCS]) (19). Nevertheless, as these data were used to categorize the sample depending on their post-lockdown evolution, different variables were created from the rate of longitudinal changes according to the cut-off points indicated in Table 1, calculating the change as follow-up minus lockdown values.

Covariates

Further information regarding sociodemographic data was also recorded as potential confounders. Age, sex, educational level (illiterate, primary school completed, secondary school completed, university completed), income (≤600€/month, >600 and <900€/month, and ≥900€/month), and marital status (single, married/living together, divorced/separated, widowed) were collected.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics package version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and graphical methods (normal probability plots) were used to determine the normal distribution of the variables. Standard descriptive statistics [mean ± standard deviation or prevalence (%)] were performed to summarize the sample characteristics and the differences between baseline and follow-up data. To examine the associations between diet quality, PA, and ST, the subsequent changes in the health-related behaviours and lifestyle after emerging from the lockdown, multinomial logistic regressions

to assess the odds ratios (OR) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated adjusted for several confounders. In these analyses, the groups of participants whose lifestyle behaviours did not change between the lockdown and post-lockdown period were used as reference. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The main characteristics of the participants, both during lockdown and at follow-up, and changes in the lifestyle and health-related behaviours induced by the return to the “new normality” are shown in Table 2. The diet quality, PA, ST, and weight significantly improved through the return to the “new normality”, while PCS significantly worsened during this period (p<0.05). No changes were found in sleep time and quality, MCS and anxiety level. The relationship between diet quality, PA, and ST and the subsequent changes in the health-related behaviours and lifestyle after emerging from the lockdown is reported in Table 3 and Figure 1. Those with a low diet quality during lock-down were more likely to show a worsening of their ST (OR: 2.03 [95% CI: 1.14; 3.62]) and worsen their anxiety level (OR: 0.41 [95% CI: 0.20; 0.83]) at follow-up; while those with a high quality of diet were less likely to remain abstainers (OR: 0.53 [95% CI: 0.33; 0.84]), worsen their weight (OR: 0.45 [95% CI: 0.22; 0.91]) and improve their PA (OR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.41; 0.98]). Concerning ST, participants with lower levels of sedentarism during the lockdown were more likely to remain abstainers (OR: 1.95 [95% CI: 1.15; 3.30]), gain weight (OR: 2.34 [95% CI: 1.07; 5.12]) and improve their social contact (OR: 2.53 [95% CI: 1.07; 5.99]); however, those with higher ST were more likely to improve their sleep quality (OR: 1.81 [95% CI: 1.10; 2.98]). Finally, participants with lower PA were more likely to both decrease their alcohol intake frequency and remain abstainers (OR: 3.01 [95% CI: 1.62; 5.59] and 3.30 [95% CI: 1.97; 5.51], respectively); while those with higher PA were more likely to increase their alcohol frequency and remain abstainers (OR: 1.82 [95% CI: 1.08; 3.06] and 2.16 [95% CI: 1.36; 3.44], respectively).

Significant associations between participants baseline characteristics and changes that occurred after the COVID-19 lockdown period

Several significant associations have been identified between dietary quality, sedentary time and physical activity baseline levels, and changes in the lifestyle and health-related characteristics between the COVID19 lockdown and the post-lockdown period. As shown above, a low diet quality during the lockdown was associated with a higher probability of worsening the sedentary time and a lower probability of worsening anxiety levels post-lockdown. However, a high-quality diet was associated with a lower likelihood of worsening weight, improving physical activity, and remaining abstainers. Besides, a low baseline sedentarism was associated with a higher probability of gaining weight, improving social contact, and remaining abstainers, while having a high sedentary time at baseline was only associated with an increased likelihood of improving the sleep quality. Finally, people with low level of physical activity during the lockdown were more likely to decrease their frequency of alcohol consumption, contrary to those with a high level of physical activity who were more likely to increase their frequency of alcohol consumption. However, both groups were associated with a higher probability of remaining abstainers after lockdown. This figure was created from the results shown in Table 3. Figure created by a co-author.

Discussion

This study examined the changes in lifestyle and health-related behaviours through the return to the “new normality”, as well as, how the diet quality, PA, and ST during the Spanish strict COVID-19 lockdown period has been associated with the main changes in health behaviours and lifestyle adaptations 7-months later in older people. Our main novel finding is that older people significantly improved during the return to the “new normality” the diet quality, PA, and ST, although the PCS component worsened. In particular, diet quality during lockdown was associated with changes in alcohol consumption, weight, ST, PA, and anxiety, while ST showed an association with changes in alcohol consumption, weight, sleep quality and social contact. However, PA during lockdown was only associated with changes in alcohol consumption. Furthermore, changes in diet quality, night-time sleep, PCS and MCS did not seem to be associated with these lifestyles during the lockdown.

The abrupt change of lifestyle during the two months of strict lockdown has been studied previously in Spain (10, 13), although this is the first study to observe the return to the “new normality” in these population. Therefore, in this study, we examined the consequences of lockdown in the medium term to determine the current situation and to identify strategies to prevent further effects in the future. In general, participants significantly improved the three main lifestyle components related to health (diet quality, PA, and ST) after the strict lockdown. Nevertheless, the PCS worsened, even showing lower values than the average both during the lockdown and after it. Thus, it seems that although lifestyle is enhanced by the reduction of mobility restrictions, lockdown has had health consequences for this population, who perceive their own physical health as deteriorated.

In a more concrete way, we found that diet quality was the lifestyle component that was associated with the most health-related behaviours. Poor diet quality during lockdown was associated with a worsening of ST upon return to the “new normality”, which is particularly relevant in older people given that ST is one of the main modifiable risk factors worldwide for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality (20), frailty and physically dependence (21). Moreover, considering that ageing is characterised by worsening levels of ST (22), and that older people are among the most sedentary and physically inactive segment of society (23), for our study population, it would be essential to break the sedentary lifestyle mainly in those with poorer diet quality. Likewise, poor diet quality during lockdown has also been associated with a lower likelihood of worsening anxiety level. This could seem strange because it is a health benefit found in those participants with a faulty lifestyle component during the lockdown; nonetheless, it could be explained by the enormous alleviation that the return to the “new normality” has brought to these people. Older people have been shown to develop higher anxiety levels during lockdown due to fear of death and worry during or after their isolation/self-lockdown (24). Moreover, most people from this age group spent the lockdown alone, which is often associated with anxiety (25). Conversely, a high diet quality during lockdown was associated with a lower likelihood of worsening the weight and improving PA and decreasing abstaining; thus, a positive relationship was found between diet and weight, but not between diet and PA. It is widely known that eating habits can be protective factors for health and body weight gain (26). However, we can also find eating habits that generate negative health behaviours like in this study. Behavioural compensations have been observed in response to dietary interventions or habits, reducing the PA by unconsciously thinking that a good diet is enough to improve health (27). Moreover, it seems that diet-only interventions are more prone to lead to reductions in PA compared to the opposite approach (27).

PA during lockdown has also been related to the alcohol consumption in the following months. Both low and high levels of PA were associated with continued abstinence, although older people with low PA were more likely to decrease their alcohol consumption, and those with high PA to increase this consumption. These results concur with previous studies, including those conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which inform of the strong evidence of a positive association between alcohol consumption and PA (26, 28). Furthermore, Piazza et al. (2012) reported that alcohol consumers were more physically active than their non-drinking peers (29), findings that remain evident also among the general population. Consequently, these results could again indicate a compensatory mechanism depending on the PA performed.

Concerning low ST, we found healthy lifestyle and behavioural changes, given that it has been associated with an increased likelihood of remaining abstainers, weight gain and the improved social contact. Although active people seem to drink more alcohol, being abstainers would be the healthiest option due to the adverse effects of alcohol on metabolism. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, this health risk factor should be highlighted, as it is more likely to cause depression, anxiety, and stress (30). Similarly, weight gain related to spending little time in sedentary behaviours could potentially be due to an increase in muscle mass, which is essential for older people as the clinical relevance of muscle mass together with muscle power has been shown (31). Even though the results of the present study do not show an increase in muscle mass, it could be more likely when the weight gain is related to a low ST than to a good diet. Similarly, improved social contact also provides a beneficial effect on health, decreasing loneliness and helping to improve mental health and anxiety (25), which were particularly impaired during lockdown in this population (5, 6). Finally, higher ST during lockdown was associated with better sleep quality. Perhaps this relation could be explained by the improved epidemiological situation of the pandemic after the lockdown, which would have led to a release and improvement of sleep parameters. However, previous studies also found an association between sleep time and quality with inactivity and lower levels of PA (32, 33). Furthermore, these results do not necessarily indicate improved health, as sleep duration has been strongly associated with and elevated risk of all-cause mortality, which in turn was associated with sleep quality (33, 34). Therefore, understanding the determinants of health-related behaviours and lifestyle during the COVID-19 pandemic is crucial for developing public health interventions (4) that can prevent further long-term consequences, as can already be found in older people in the medium-term. In particular, given these results, it seems that a low ST may provide more relevant health benefits in older people. Furthermore, a low ST also leads to other advantages such as reduced frailty status, a positive bone ageing and better physical function (21, 35).

Even though these consequences were found in a particular older Spanish population, other studies conducted in different populations also determined some improvements in lifestyle with the relief of restrictions. Regarding the Italian student population, it was found that although depressive symptomatology may be aggravated during lockdown after lifting it, any change quickly vanished (36). Similarly, in England’s general population, the probability of exercising for a long duration (≥ 3 h) increased in the first 13 weeks of lockdown, which was followed by a decrease when confinement measures were substantially eased in June 2020 (37). However, the characteristics and factors specific to each subject should be studied to better understand more specific consequences (18). Therefore, for all the above, we must bear in mind that the effects on lifestyle after COVID19 lockdown may depend on the type of population we are targeting.

Our study is not without limitations. Variables were collected using a telephone-based structured interview, although most of the questions were obtained from validated questionnaires (15, 17, 19). Moreover, all participants had already completed this interview at home for their respective cohorts before the COVID-19 pandemic, thus being familiar with the procedure and reducing the risk of reporting bias. Additionally, our results should be interpreted with caution and not generalized for other populations, because of the particularly strict lockdown implemented in Spain. To our knowledge, this is the first study to look at the effects of the lockdown in older people during the return to the “new normality”. Likewise, the sample was relatively large and homogeneous, not including institutionalized people with different lifestyle conditions and those infected during the period covered by the study.

Conclusion

This study shows the medium-term effects of the lockdown, and more particularly depending on the diet quality, PA, and ST conducted during this lockdown period in the health-related behaviours and lifestyle of Spanish older people. Despite the expected improvement in lifestyle during the return to the “new normality”, older people perceived their physical health to be impaired. Furthermore, diet quality during lockdown was associated with ST, anxiety, weight, PA, and alcohol consumption, whereas ST was associated with weight, social contact, alcohol consumption and sleep quality. Surprisingly, PA was only related to alcohol consumption. In this regard, it appears that lower ST during lockdown seemed to provide the most remarkable lifestyle improvement in the medium term. Therefore, public health interventions in this direction should be designed to prevent further long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in older people.

References

Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):386–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.009.

Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestioón de la situacioón de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19., (2020).

Boletín Oficial del Estado. Orden SND/380/2020, de 30 de Abril, sobre las Condiciones en las que se puede realizar actividad física no Profesional al aire libre durante la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19., (2020).

Sasaki S, Sato A, Tanabe Y, Matsuoka S, Adachi A, Kayano T, et al. Associations between Socioeconomic Status, Social Participation, and Physical Activity in Older People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Northern Japanese City. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1477. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041477.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020;14(5):779–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035.

Dekker J, Buurman BM, van der Leeden M. Exercise in people with comorbidity or multimorbidity. Health Psychology. 2019;38(9):822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000750.

Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(2):103–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001.

Sánchez-Sánchez E, Ramírez-Vargas G, Avellaneda-López Y, Orellana-Pecino JI, García-Marín E, Díaz-Jimenez J. Eating habits and physical activity of the Spanish population during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2826. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092826.

Rodríguez-González R, Facal D, Martínez-Santos A-E, Gandoy-Crego M. Psychological, social and health-related challenges in Spanish older adults during the lockdown of the COVID-19 first wave. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1393. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.588949.

Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? The lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9.

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213.

Carriedo A, Cecchini JA, Fernandez-Rio J, Méndez-Giménez A. COVID-19, psychological well-being and physical activity levels in older adults during the nationwide lockdown in Spain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(11):1146–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.007.

Schrack JA, Wanigatunga AA, Juraschek SP. After the COVID-19 pandemic: the next wave of health challenges for older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(9):e121–e2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa102.

Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011;141(6):1140–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.135566.

Rodríguez-Pérez C, Molina-Montes E, Verardo V, Artacho R, García-Villanova B, Guerra-Hernández EJ, et al. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1730. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061730.

Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4.

García-Esquinas E, Ortolá R, Gine-Vázquez I, Carnicero JA, Mañas A, Lara E, et al. Changes in Health Behaviors, Mental and Physical Health among Older Adults under Severe Lockdown Restrictions during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137067.

Ware JE. The SF-12v2TM how to score version 2 of the SF-12® health survey:(with a supplement documenting version 1): Quality metric; 2002.

Lavie CJ, Ozemek C, Carbone S, Katzmarzyk PT, Blair SN. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2019;124(5):799–815. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312669.

Mañas A, del Pozo-Cruz B, Rodríguez-Gómez I, Leal-Martín J, Losa-Reyna J, Rodríguez-Mañas L, et al. Dose-response association between physical activity and sedentary time categories on ageing biomarkers. BMC geriatrics. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1284-y.

Aadahl M, Andreasen AH, Hammer-Helmich L, Buhelt L, Jørgensen T, Glümer C. Recent temporal trends in sleep duration, domain-specific sedentary behaviour and physical activity. A survey among 25–79-year-old Danish adults. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(7):706–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813493151.

Cvecka J, Tirpakova V, Sedliak M, Kern H, Mayr W, Hamar D. Physical activity in elderly. Eur J Transl Myol. 2015;25(4):249. doi: https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2015.5280.

Liu K, Chen Y, Wu D, Lin R, Wang Z, Pan L. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101132. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101132.

Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Loneliness during strict lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 adults in the UK. medRxiv. 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521.

Reyes-Olavarría D, Latorre-Román PÁ, Guzmán-Guzmán IP, Jerez-Mayorga D, Caamaño-Navarrete F, Delgado-Floody P. Positive and negative changes in food habits, physical activity patterns, and weight status during COVID-19 confinement: associated factors in the Chilean population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5431. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155431.

Silva AM, Júdice PB, Carraça EV, King N, Teixeira PJ, Sardinha LB. What is the effect of diet and/or exercise interventions on behavioural compensation in non-exercise physical activity and related energy expenditure of free-living adults? A systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2018;119(12):1327–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711451800096x.

Niedermeier M, Frühauf A, Kopp-Wilfling P, Rumpold G, Kopp M. Alcohol consumption and physical activity in Austrian college students—A cross-sectional study. Subst Use Misus. 2018;53(10):1581–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1416406.

Piazza-Gardner AK, Barry AE. Examining physical activity levels and alcohol consumption: are people who drink more active? Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(3):e95–e104. doi: https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.100929-LIT-328.

Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4065. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114065.

Losa-Reyna J, Alcazar J, Rodríguez-Gómez I, Alfaro-Acha A, Alegre LM, Rodríguez-Mañas L, et al. Low relative mechanical power in older adults: An operational definition and algorithm for its application in the clinical setting. Exp Gerontol. 2020;142:111141. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2020.111141.

Zach S, Zeev A, Ophir M, Eilat-Adar S. Physical activity, resilience, emotions, moods, and weight control of older adults during the COVID-19 global crisis. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2021;18(1):1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-021-00258-w.

Morgan K, Hartescu I. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: links to physical activity and prefrailty in a 27-year follow up of older adults in the UK. Sleep medicine. 2019;54:231–7. doi: u]https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2018.11.008.

Chen H-C, Su T-P, Chou P. A nine-year follow-up study of sleep patterns and mortality in community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan. Sleep. 2013;36(8):1187–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2884.

Rodríguez-Gómez I, Mañas A, Losa-Reyna J, Alegre LM, Rodríguez-Mañas L, García-García FJ, et al. Relationship between physical performance and frailty syndrome in older adults: the mediating role of physical activity, sedentary time and body composition. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):203. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010203.

Meda N, Pardini S, Slongo I, Bodini L, Zordan MA, Rigobello P, et al. Students’ mental health problems before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;134:69–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.045.

Bu F, Bone JK, Mitchell JJ, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Longitudinal changes in physical activity during and after the first national lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17723. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97065-1.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Project funded by the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha, entitled: “Impacto del confinamiento domiciliario del COVID-19 sobre la salud de los adultos mayores: Un experimento natural en España.” (Reference:2020/9024). The TSHA and the EXERNET cohorts were supported by the Biomedical Research Networking Center on Frailty and Healthy Aging (CIBERFES) and FEDER funds from the European Union (CB16/10/00477, CB16/10/00464 and CB16/10/00456). TSHA was further funded by grants from the Government of Castilla-La Mancha (PI2010/020; Institute of Health Sciences, Ministry of Health of Castilla-La Mancha, 03031–00), Spanish Government (Spanish Ministry of Economy, “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad,” Instituto de Salud Carlos III, PI10/01532, PI031558, PI11/01068), and by European Grants (Seventh Framework Programme: FRAILOMIC). Likewise, EXERNET was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, “Economía, Industria y Competitividad” (DEP2016-78309-R), the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (Red EXERNET DEP2005-00046), the High Council of Sports (Consejo Superior de Deportes) (45/UPB/20), CIBERFES, the 4IE+ project (0499_4IE_PLUS_4_E) funded by the Interreg V-A España-Portugal (POCTEP) 2014–2020 program. Finally, Irene Rodríguez Gómez got a postdoctoral contract from the Government of Castilla-La Mancha (2019/9601) and Coral Sánchez-Martín received a PhD grant from the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha “Contratos predoctorales para la formación de personal investigador en el marco del Plan Propio de I+D+i, cofinanciados por el Fondo Social Europeo” (2020/3836).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Toledo Hospital Complex (Protocol #2203/30/2005) and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (#18/2008).

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Gómez, I., Sánchez-Martín, C., García-García, F.J. et al. The Medium-Term Changes in Health-Related Behaviours among Spanish Older People Lifestyles during Covid-19 Lockdown. J Nutr Health Aging 26, 485–494 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1781-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1781-0