Abstract

Myocardial blood flow (MBF) and coronary flow reserve (CFR), the ratio of MBF during hyperemia to basal MBF, are integrated measures of flow through both the large epicardial coronary arteries and the microcirculation. To date, positron emission tomography (PET) offers the most robust and best investigated method for quantifying MBF in vivo. The potential of MBF quantification to improve detection of patients with high-risk coronary artery disease (CAD) or to identify patients with variable degrees of microvascular or endothelial dysfunction are promising new clinical avenues which await further evaluation in larger prospective trials. The current experience with MBF quantification also demonstrates potential benefits in other groups of patients. The present article summarizes the published literature on MBF quantification in CAD and other cardiac conditions and outlines in which fields MBF quantification could offer important value to improve the treatment and prognosis of patients. Novel PET perfusion compounds that are not bound to an onsite cyclotron will improve availability of MBF quantification, promote its use in the clinical setting, and facilitate further studies to establish its clinical value.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:830–40.

Camici PG, Rimoldi OE. The clinical value of myocardial blood flow measurement. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1076–87.

Chilian WM, Layne SM, Klausner EC, Eastham CL, Marcus ML. Redistribution of coronary microvascular resistance produced by dipyridamole. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H383–90.

Marcus ML, Chilian WM, Kanatsuka H, Dellsperger KC, Eastham CL, Lamping KG. Understanding the coronary circulation through studies at the microvascular level. Circulation. 1990;82:1–7.

Chilian WM. Coronary microcirculation in health and disease. Summary of an NHLBI workshop. Circulation. 1997;95:522–8.

Klocke FJ, Baird MG, Lorell BH, et al. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging–executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1318–33.

Iskander S, Iskandrian AE. Risk assessment using single-photon emission computed tomographic technetium-99m sestamibi imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:57–62.

Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–7.

Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–55.

Marcus ML, Wilson RF, White CW. Methods of measurement of myocardial blood flow in patients: a critical review. Circulation. 1987;76:245–53.

Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Smith L, et al. Coronary thermodilution to assess flow reserve: validation in humans. Circulation. 2002;105:2482–6.

Kaufmann PA, Camici PG. Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: technical aspects and clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:75–88.

Koepfli P, Hany TF, Wyss CA, et al. CT attenuation correction for myocardial perfusion quantification using a PET/CT hybrid scanner. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:537–42.

• Gaemperli O, Kaufmann PA. PET and PET/CT in cardiovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1228:109-36. Comprehensive review of current clinical indications of PET and PET/CT in cardiovascular disease.

Bergmann SR, Herrero P, Markham J, Weinheimer CJ, Walsh MN. Noninvasive quantitation of myocardial blood flow in human subjects with oxygen-15-labeled water and positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:639–52.

Araujo LI, Lammertsma AA, Rhodes CG, et al. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial blood flow in coronary artery disease with oxygen-15-labeled carbon dioxide inhalation and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1991;83:875–85.

Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Yap JT, Rimoldi O, Camici PG. Assessment of the reproducibility of baseline and hyperemic myocardial blood flow measurements with 15O-labeled water and PET. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1848–56.

Jagathesan R, Kaufmann PA, Rosen SD, et al. Assessment of the long-term reproducibility of baseline and dobutamine-induced myocardial blood flow in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:212–9.

Wyss CA, Koepfli P, Mikolajczyk K, Burger C, von Schulthess GK, Kaufmann PA. Bicycle exercise stress in PET for assessment of coronary flow reserve: repeatability and comparison with adenosine stress. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:146–54.

Schafers KP, Spinks TJ, Camici PG, et al. Absolute quantification of myocardial blood flow with H(2)(15)O and 3-dimensional PET: an experimental validation. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1031–40.

Bol A, Melin JA, Vanoverschelde JL, et al. Direct comparison of [13N]ammonia and [15O]water estimates of perfusion with quantification of regional myocardial blood flow by microspheres. Circulation. 1993;87:512–25.

Bergmann SR, Fox KA, Rand AL, et al. Quantification of regional myocardial blood flow in vivo with H215O. Circulation. 1984;70:724–33.

Muzik O, Beanlands RS, Hutchins GD, Mangner TJ, Nguyen N, Schwaiger M. Validation of nitrogen-13-ammonia tracer kinetic model for quantification of myocardial blood flow using PET. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:83–91.

Bellina CR, Parodi O, Camici P, et al. Simultaneous in vitro and in vivo validation of nitrogen-13-ammonia for the assessment of regional myocardial blood flow. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1335–43.

Choi Y, Huang SC, Hawkins RA, et al. Quantification of myocardial blood flow using 13N-ammonia and PET: comparison of tracer models. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1045–55.

Hutchins GD, Schwaiger M, Rosenspire KC, Krivokapich J, Schelbert H, Kuhl DE. Noninvasive quantification of regional blood flow in the human heart using N-13 ammonia and dynamic positron emission tomographic imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1032–42.

Nitzsche EU, Choi Y, Czernin J, Hoh CK, Huang SC, Schelbert HR. Noninvasive quantification of myocardial blood flow in humans. A direct comparison of the [13N]ammonia and the [15O]water techniques. Circulation. 1996;93:2000–6.

Camici PG, Rimoldi OE. Myocardial blood flow in patients with hibernating myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:302–11.

Lautamaki R, George RT, Kitagawa K, et al. Rubidium-82 PET-CT for quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow: validation in a canine model of coronary artery stenosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:576–86.

Herrero P, Markham J, Shelton ME, Weinheimer CJ, Bergmann SR. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82 and positron emission tomography. Exploration of a mathematical model. Circulation. 1990;82:1377–86.

Goldstein RA, Mullani NA, Marani SK, Fisher DJ, Gould KL, O'Brien Jr HA. Myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82. II. Effects of metabolic and pharmacologic interventions. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:907–15.

El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with (82)Rb PET: comparison with (13)N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1062–71.

Nekolla SG, Reder S, Saraste A, et al. Evaluation of the novel myocardial perfusion positron-emission tomography tracer 18F-BMS-747158-02: comparison to 13N-ammonia and validation with microspheres in a pig model. Circulation. 2009;119:2333–42.

Sherif HM, Nekolla SG, Saraste A, et al. Simplified quantification of myocardial flow reserve with flurpiridaz F 18: validation with microspheres in a pig model. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:617–24.

McCommis KS, Goldstein TA, Abendschein DR, et al. Quantification of regional myocardial oxygenation by magnetic resonance imaging: validation with positron emission tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:41–6.

Jerosch-Herold M. Quantification of myocardial perfusion by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:57.

Jerosch-Herold M, Swingen C, Seethamraju RT. Myocardial blood flow quantification with MRI by model-independent deconvolution. Med Phys. 2002;29:886–97.

Smits P, Williams SB, Lipson DE, Banitt P, Rongen GA, Creager MA. Endothelial release of nitric oxide contributes to the vasodilator effect of adenosine in humans. Circulation. 1995;92:2135–41.

Siegrist PT, Gaemperli O, Koepfli P, et al. Repeatability of cold pressor test-induced flow increase assessed with H(2)(15)O and PET. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1420–6.

Dayanikli F, Grambow D, Muzik O, Mosca L, Rubenfire M, Schwaiger M. Early detection of abnormal coronary flow reserve in asymptomatic men at high risk for coronary artery disease using positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1994;90:808–17.

Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Schafers KP, Luscher TF, Camici PG. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary microvascular dysfunction in hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:103–9.

Guethlin M, Kasel AM, Coppenrath K, Ziegler S, Delius W, Schwaiger M. Delayed response of myocardial flow reserve to lipid-lowering therapy with fluvastatin. Circulation. 1999;99:475–81.

Yokoyama I, Ohtake T, Momomura S, Nishikawa J, Sasaki Y, Omata M. Reduced coronary flow reserve in hypercholesterolemic patients without overt coronary stenosis. Circulation. 1996;94:3232–8.

Yokoyama I, Murakami T, Ohtake T, et al. Reduced coronary flow reserve in familial hypercholesterolemia. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1937–42.

Gimelli A, Schneider-Eicke J, Neglia D, et al. Homogeneously reduced versus regionally impaired myocardial blood flow in hypertensive patients: two different patterns of myocardial perfusion associated with degree of hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:366–73.

Pitkanen OP, Nuutila P, Raitakari OT, et al. Coronary flow reserve is reduced in young men with IDDM. Diabetes. 1998;47:248–54.

Di Carli MF, Janisse J, Grunberger G, Ager J. Role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1387–93.

Yokoyama I, Momomura S, Ohtake T, et al. Reduced myocardial flow reserve in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1472–7.

Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, di Terlizzi M, Schafers KP, Luscher TF, Camici PG. Coronary heart disease in smokers: vitamin C restores coronary microcirculatory function. Circulation. 2000;102:1233–8.

Campisi R, Czernin J, Schoder H, Sayre JW, Schelbert HR. L-Arginine normalizes coronary vasomotion in long-term smokers. Circulation. 1999;99:491–7.

Recio-Mayoral A, Mason JC, Kaski JC, Rubens MB, Harari OA, Camici PG. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1837–43.

Lorenzoni R, Rosen SD, Camici PG. Effect of alpha 1-adrenoceptor blockade on resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in normal humans. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1302–6.

Bottcher M, Czernin J, Sun K, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Effect of beta 1 adrenergic receptor blockade on myocardial blood flow and vasodilatory capacity. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:442–6.

Koepfli P, Wyss CA, Namdar M, et al. Beta-adrenergic blockade and myocardial perfusion in coronary artery disease: differential effects in stenotic versus remote myocardial segments. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1626–31.

Gould KL, Martucci JP, Goldberg DI, et al. Short-term cholesterol lowering decreases size and severity of perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after dipyridamole in patients with coronary artery disease. A potential noninvasive marker of healing coronary endothelium. Circulation. 1994;89:1530–8.

Leung WH, Lau CP, Wong CK. Beneficial effect of cholesterol-lowering therapy on coronary endothelium-dependent relaxation in hypercholesterolaemic patients. Lancet. 1993;341:1496–500.

Egashira K, Hirooka Y, Kai H, et al. Reduction in serum cholesterol with pravastatin improves endothelium-dependent coronary vasomotion in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1994;89:2519–24.

Treasure CB, Klein JL, Weintraub WS, et al. Beneficial effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy on the coronary endothelium in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:481–7.

Anderson TJ, Meredith IT, Yeung AC, Frei B, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. The effect of cholesterol-lowering and antioxidant therapy on endothelium-dependent coronary vasomotion. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:488–93.

Czernin J, Barnard RJ, Sun KT, et al. Effect of short-term cardiovascular conditioning and low-fat diet on myocardial blood flow and flow reserve. Circulation. 1995;92:197–204.

Kaufmann PA, Frielingsdorf J, Mandinov L, Seiler C, Hug R, Hess OM. Reversal of abnormal coronary vasomotion by calcium antagonists in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;97:1348–54.

Frielingsdorf J, Seiler C, Kaufmann P, Vassalli G, Suter T, Hess OM. Normalization of abnormal coronary vasomotion by calcium antagonists in patients with hypertension. Circulation. 1996;93:1380–7.

Beltrame JF, Turner SP, Leslie SL, Solomon P, Freedman SB, Horowitz JD. The angiographic and clinical benefits of mibefradil in the coronary slow flow phenomenon. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:57–62.

Neglia D, Fommei E, Varela-Carver A, et al. Perindopril and indapamide reverse coronary microvascular remodelling and improve flow in arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2011;29:364–72.

Pauly DF, Johnson BD, Anderson RD, et al. In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and microvascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: A double-blind randomized study from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Am Heart J. 2011;162:678–84.

Walsh MN, Geltman EM, Steele RL, et al. Augmented myocardial perfusion reserve after coronary angioplasty quantified by positron emission tomography with H2(15)O. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:119–27.

Uren NG, Crake T, Lefroy DC, de Silva R, Davies GJ, Maseri A. Delayed recovery of coronary resistive vessel function after coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:612–21.

Pasternac A, Noble J, Streulens Y, Elie R, Henschke C, Bourassa MG. Pathophysiology of chest pain in patients with cardiomyopathies and normal coronary arteries. Circulation. 1982;65:778–89.

Cannon 3rd RO, Schenke WH, Maron BJ, et al. Differences in coronary flow and myocardial metabolism at rest and during pacing between patients with obstructive and patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:53–62.

•• Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Camici PG. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1027-35. This study was one of the first reports demonstrating the prognostic value of myocardial blood flow by PET. Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have an impaired prognosis if hyperaemic flow is lower than 1.11 mL/min/g.

Neglia D, Parodi O, Gallopin M, et al. Myocardial blood flow response to pacing tachycardia and to dipyridamole infusion in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy without overt heart failure. A quantitative assessment by positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1995;92:796–804.

Jenni R, Wyss CA, Oechslin EN, Kaufmann PA. Isolated ventricular noncompaction is associated with coronary microcirculatory dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:450–4.

Brush Jr JE, Cannon 3rd RO, Schenke WH, et al. Angina due to coronary microvascular disease in hypertensive patients without left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1302–7.

Opherk D, Mall G, Zebe H, et al. Reduction of coronary reserve: a mechanism for angina pectoris in patients with arterial hypertension and normal coronary arteries. Circulation. 1984;69:1–7.

Choudhury L, Rosen SD, Patel D, Nihoyannopoulos P, Camici PG. Coronary vasodilator reserve in primary and secondary left ventricular hypertrophy. A study with positron emission tomography. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:108–16.

Neglia D, Michelassi C, Trivieri MG, et al. Prognostic role of myocardial blood flow impairment in idiopathic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:186–93.

Maron MS, Olivotto I, Maron BJ, et al. The case for myocardial ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:866–75.

Uren NG, Marraccini P, Gistri R, de Silva R, Camici PG. Altered coronary vasodilator reserve and metabolism in myocardium subtended by normal arteries in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:650–8.

Pupita G, Maseri A, Kaski JC, et al. Myocardial ischemia caused by distal coronary-artery constriction in stable angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:514–20.

Kloner RA, Rude RE, Carlson N, Maroko PR, DeBoer LW, Braunwald E. Ultrastructural evidence of microvascular damage and myocardial cell injury after coronary artery occlusion: which comes first? Circulation. 1980;62:945–52.

Kloner RA, Ganote CE, Jennings RB. The “no-reflow” phenomenon after temporary coronary occlusion in the dog. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:1496–508.

Gregorini L, Marco J, Kozakova M, et al. Alpha-adrenergic blockade improves recovery of myocardial perfusion and function after coronary stenting in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999;99:482–90.

Galiuto L. Optimal therapeutic strategies in the setting of post-infarct no reflow: the need for a pathogenetic classification. Heart. 2004;90:123–5.

Ito H, Maruyama A, Iwakura K, et al. Clinical implications of the ‘no reflow’ phenomenon. A predictor of complications and left ventricular remodeling in reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1996;93:223–8.

Rimoldi O, Spyrou N, Foale R, Hackett DR, Gregorini L, Camici PG. Limitation of coronary reserve after successful angioplasty is prevented by oral pretreatment with an alpha1-adrenergic antagonist. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:310–5.

Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, et al. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:473–81.

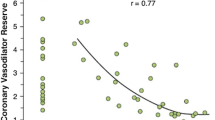

•• Uren NG, Melin JA, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Baudhuin T, Camici PG. Relation between myocardial blood flow and the severity of coronary-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1782-8. One of the first studies to investigate the relationship between the angiographic severity of coronary stenoses and its impact on myocardial blood flow (MBF) by PET. Although MBF declines with increasing stenosis severity there is a wide variability of values.

Di Carli M, Czernin J, Hoh CK, et al. Relation among stenosis severity, myocardial blood flow, and flow reserve in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1995;91:1944–51.

Anagnostopoulos C, Almonacid A. El Fakhri G, et al. Quantitative relationship between coronary vasodilator reserve assessed by 82Rb PET imaging and coronary artery stenosis severity. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1593–601.

White CW, Wright CB, Doty DB, et al. Does visual interpretation of the coronary arteriogram predict the physiologic importance of a coronary stenosis? N Engl J Med. 1984;310:819–24.

Tonino PA, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2816–21.

Bengel FM. Leaving relativity behind: quantitative clinical perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:749–51.

Ragosta M, Bishop AH, Lipson LC, et al. Comparison between angiography and fractional flow reserve versus single-photon emission computed tomographic myocardial perfusion imaging for determining lesion significance in patients with multivessel coronary disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:896–902.

Dorbala S, Vangala D, Sampson U, Limaye A, Kwong R, Di Carli MF. Value of vasodilator left ventricular ejection fraction reserve in evaluating the magnitude of myocardium at risk and the extent of angiographic coronary artery disease: a 82Rb PET/CT study. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:349–58.

Lima RS, Watson DD, Goode AR, et al. Incremental value of combined perfusion and function over perfusion alone by gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of severe three-vessel coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:64–70.

Melikian N, De Bondt P, Tonino P, et al. Fractional flow reserve and myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with angiographic multivessel coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:307–14.

Yoshinaga K, Katoh C, Noriyasu K, et al. Reduction of coronary flow reserve in areas with and without ischemia on stress perfusion imaging in patients with coronary artery disease: a study using oxygen 15-labeled water PET. J Nucl Cardiol. 2003;10:275–83.

Parkash R. deKemp RA, Ruddy TD, et al. Potential utility of rubidium 82 PET quantification in patients with 3-vessel coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:440–9.

Hajjiri MM, Leavitt MB, Zheng H, Spooner AE, Fischman AJ, Gewirtz H. Comparison of positron emission tomography measurement of adenosine-stimulated absolute myocardial blood flow versus relative myocardial tracer content for physiological assessment of coronary artery stenosis severity and location. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:751–8.

Kajander SA, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, et al. Clinical Value of Absolute Quantification of Myocardial Perfusion With 15O-Water in Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:678–84.

Gaemperli O, Bengel FM, Kaufmann PA. Cardiac hybrid imaging. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2100–8.

Kajander S, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging accurately detects anatomically and functionally significant coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122:603–13.

Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2825–32.

•• Herzog BA, Husmann L, Valenta I, et al. Long-term prognostic value of 13N-ammonia myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography added value of coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:150-6. This study should be highlighted because it is the first one to show that quantitative myocardial blood flow measurements by PET have an incremental prognostic value over qualitative perfusion imaging in patients with known or suspected CAD.

Tio RA, Dabeshlim A, Siebelink HM, et al. Comparison between the prognostic value of left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion reserve in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:214–9.

Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, et al. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:740–8.

Beanlands RS, Ziadi MC, Williams K. Quantification of myocardial flow reserve using positron emission imaging the journey to clinical use. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:157–9.

Denardo SJ, Wen X, Handberg EM, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: a Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) ancillary study. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:483–7.

Evgenov OV, Pacher P, Schmidt PM, Hasko G, Schmidt HH, Stasch JP. NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble guanylate cyclase: discovery and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:755–68.

Schindler TH, Nitzsche EU, Schelbert HR, et al. Positron emission tomography-measured abnormal responses of myocardial blood flow to sympathetic stimulation are associated with the risk of developing cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1505–12.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaemperli, O., Kaufmann, P.A. Why Quantify Myocardial Perfusion?. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 5, 133–143 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-012-9130-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-012-9130-z