Abstract

The amount of personal data now collected through contemporary marketing practices is indicative of the shifting landscape of contemporary capitalism. Loyalty programs can be seen as one exemplar of this, using the ‘add-ons’ of ‘points’ and ‘miles’ to entice consumers into divulging a range of personal information. These consumers are subject to surveillance practices that have digitally identified them as significant in the eyes of a corporation, yet they are also part of a feedback loop subject to ongoing analysis. This paper focuses on this analysis as the ‘cultural circuit’ of loyalty programs—the ongoing process of meaning-making in this form of contemporary marketing—as exemplary of what Nigel Thrift calls “soft capitalism”(1997, 2005). Loyalty programs engage consumers in an ongoing ‘relationship’ with a corporation, yet it is one predicated on the collection and analysis of personal data in order to identify, maintain and increase profits from these consumer ‘relationships.’ This paper looks at ways of knowing, application and revision in the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing as a form of reflexive marketing and raises concerns about consumer subjectivity in the context consumer culture that mediates much of contemporary experience. These technologies and practices continually adapt and adjust to strategically act toward consumers as a form of consumer surveillance based on an increasingly intensive and nuanced knowledge of their behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The amount of personal data collected through contemporary marketing practices is indicative of the shifting landscape of contemporary capitalism. In what can be seen as the development of a ‘personal information economy’ (see Perri 6 2005; and Elmer 2004), ‘informationally’ powerful entities rely on data to define and identify current or potential consumers. Loyalty programs can be seen as one exemplar of this, using the ‘add-ons’ of ‘points’ and ‘miles’ to entice consumers into divulging a range of personal information. This information is used to classify types of consumers and to sort them into segmented and stratified categories that to different extents affect their consumption patterns and opportunities. While the effects of how consumers are identified occur in both overt and subtle ways, the relationship between consumers and these ‘informationally’ powerful corporations is dynamic and nuanced. Consumers are subject to surveillance practices that have digitally identified them as significant in the eyes of a corporation (see Zwick and Dholakia 2004b), yet they are also part of a feedback loop subject to ongoing analysis. In this sense, they are part of “continually interacting processes in a ‘cultural circuit’” that “both reflect and transform consumers’ behaviour” (Zukin and Maguire 2004:178). That is, while the profiles created through the processing of personal information may be used to meaningfully and in some cases profoundly shape the consumer behaviour in the marketplace, those very behaviours, along with attitudes, responses, interactions, personal goals and more are integrated into a knowledge system that serves to alter, modify, and transform marketing practice.

This paper focuses on the ‘cultural circuit’ of loyalty programs—the ongoing process of meaning-making in this form of contemporary marketing—as exemplary of what Nigel Thrift calls “soft capitalism”(1997, 2005). This form of soft capitalism both emerges as highly adaptive to the inherent complexity of contemporary markets and demonstrates what Thrift calls a more “caring, sharing ethos” (2005:11). Loyalty programs engage consumers in an ongoing ‘relationship’—one predicated on the collection of personal data, and these data serve as the means for corporations to identify, maintain and increase “the yield from best customers through interactive, value added relationships” (Capizzi and Ferguson 2005:72). Consumers are, in a very Foucauldian sense, subject to a system of control that remains largely imperceptible. At the same time however, these programs are continually augmented and modified through consumer engagement in a way that renders this control far less apparent.

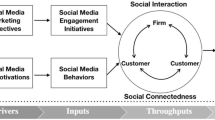

In this paper, the intertwined relational process between the consumer and the corporation—a “mutual adaptation between what a firm proposes and what consumers want” (Callon et al. 2002:200–201)—is described as a form of reflexive marketing. While the mutual adaptation of supply and demand Callon and his collaborators discuss may “always seems somewhat miraculous” (ibid.), the interconnected relationship between these two are hinged on the continual shaping and modification of marketing practice in order to identify and engage particular types and sets of consumers. This paper draws on interviews conducted with the top executives in a dozen Canadian loyalty programs that are exemplary of such a ‘highly reflexive market.’

The paper illustrates the cultural circuit of knowledge inherent in the deployment of loyalty programs. First, it begins by reviewing ‘ways knowing held by loyalty program executives and their teams. It describes the ‘tacit knowledge’ these employees have of the program and its data, knowledge based on collective experiences and overall familiarity with the program. Second, the paper indicates how the application of ‘learning by doing’ is systematically integrated into marketing practices to supplement this tacit knowledge. These forms of ‘application’ are largely based on experimental evaluations that enable employees to better understand and segment consumers. Last, the paper reviews more interactive mechanisms for consumers as part of this cultural circuit, specifically the means for consumer feedback that serve to inform corporate practices of segmentation through practices of ‘revision.’ This cultural circuit continually informs the production of increasingly nuanced and automated systems of identification for consumers. As a form of reflexive marketing, it raises concerns about consumer subjectivity as these practices are embedded in the context consumer culture that mediates much of contemporary experience and as these technologies continually adapt and adjust to strategically act toward consumers based on an increasingly intensive and nuanced knowledge of their behaviours.

Loyalty programs and contemporary marketing

Loyalty programs are increasingly ubiquitous in Western marketing practice. These programs seek to reward consumers that regularly patronize a particular corporation’s offerings by providing incentives for this behaviour in terms of service, recognition, or financial advantages. As such, they are often hailed as one of the best examples of the shift toward one-to-one or relationship marketing, and these programs are touted as an excellent example of corporate-consumer ‘relationships’ in action (Hart et al. 1999). Through the use of rewards cards and the collection of ‘points’ or ‘miles’ by consumers, these programs allow corporations to continually gauge consumer behaviour and more, generating feedback that allows corporations to modify marketing practices in order to increase marketing effectiveness and strengthen consumer participation.

Making sense of all the information received through this process is understood as “the biggest trick” for loyalty program executives. While these programs produce an immense amount of information about consumers, these “consumer fragments” can be seen to “create as many problems as they solve” (Moor 2003:53). As Elizabeth Moor, writing about the information processing of a particular brand, discusses:

[T]here is simply too much information—in order to ‘process’ some pieces of information about consumers, it would be necessary to exclude any number of others, such that some information can never be (or can escape being) re-contextualized as ‘knowledge’. On the other hand, this type of information simultaneously provides both too much and too little context, and in translating this contextual information from one site to another it may be difficult... (ibid.)

It is, as Moor suggests, an issue of translation (see Latour 1987). Increasingly corporations are faced with the dilemma of contextualizing unwieldy information into ‘knowledge.’ This is precisely the position of loyalty programs executives and their teams are put in, making sense of an over abundance of data and translating this into a form that can be put to use for marketing.

This paper, as part of a larger project examining forms of consumer surveillance and loyalty programs in specific, is based on a series of in-depth interviews with the people instrumental in running a dozen of the largest loyalty programs in Canada. Although, as John Deighton suggests, these programs are not usually viewed as consequential—seen as simply “cents off” devices for increasing consumer patronage, they are an important means for conceptualizing contemporary marketing practices, the use of personal information, and identity in an information oriented society:

[A]s we try to anticipate the threats and opportunities, commercial and societal, of pervasive portable digital identities... we have more to learn from the workings of these programs than from any other current manifestation of the coming age. They represent a glimpse of life when some version of our reputation travels with us wherever we go, whether we like it or not (2005:249).

Following this notion of Deighton, this research focuses on how marketers in the loyalty program industry navigate personal consumption practices and the means by which companies can identify these consumers in order to market to them more effectively. These interviews with executives from loyalty programs in Canada represent the largest and programs with the highest market penetration rates in a country in which over 63% of households currently use these programs in their everyday consumption. These interviews were transcribed and analyzed in relation to literature on relationship marketing, profiling, sociology of consumption, surveillance and Science and Technology studies. What becomes evident here are the interconnections between technology, data, knowledge and their application in marketing practice. Loyalty programs, as an ‘exemplary’ form of marketing, reveals the highly reflexive nature of marketing in the personal information economy.

Ways of knowing: the use of tacit knowledge

One of the first executives interviewed for this research had transitioned to her current position only six months prior to the interview. It was abundantly clear that for her a knowledge of how consumer data and information was collected and could be used was crucial. Executive A:

Analysis is absolutely key—the input of the data, how it’s created, how it then spits out into a report and how somebody analyzes this. It is so important because you could be making the wrong decisions. And so what I have seen is that ...an intimate knowledge of the business is required. I have people that have been with the program and understand the way the data is put into our system and cumulated and how individuals are looked at and how we calculate margin and all of that stuff. Every time I think, okay so I get it, then I go and say, ‘listen doesn’t that mean X? Therefore we should do Y?’ Then they will say ‘No. We don’t do this because we recalculate that because of Z, which is the way our business works and therefore that conclusion (Y) is wrong.‘ I say ’oh really?’...That’s why human beings are doing what they are doing.

Despite years of consumer research and marketing practice in another area of marketing, this ‘new’ program executive indicated her need to adjust to a system of interpretation that was foreign to her. There is no simple, straight forward ‘reading’ of data. She had to be ‘enrolled’ in the interpretive framework of her team members (Latour 1987: 108).

Her embracement of this perspective is indicative of the increasing managerial reflexivity and recognition of the complexity in markets that Nigel Thrift describes as part of a “soft capitalism” (Thrift 1997, 2005). In his view, soft capitalism has emerged in part through the continuous knowledge creation and learning that occurs in corporate practice. It relies heavily on inter-personal relations and trust and is “performative;” that is, it is able to “change its practices constantly” so that it might “surf the right side of constant change” (2005:3). In other interviews for this research, loyalty program executives continually verbalized what Thrift describes as the new managerial discourse in descriptions of their work, emphasizing the importance of tacit knowledge and a corporate culture centred on learning.

The importance of this “tacit knowledge” which, according to Thrift is “familiar but unarticulated knowledge embodied in [the] workforce” (ibid.:33–34) was evident in several interviews. Another executive took a very systematic approach to the production of this new ‘knowledge’ about consumer behaviour.

Executive B: A bit of it is intuition. We try to see a collection of behaviour and say, okay this looks like as if it’s a distinct kind of cluster of behaviour and we ask what it suggests. And then we execute a campaign usually to test it. So we’ll send a generic campaign versus one we think is suited to them versus a third targeted one that is completely erroneous to as small population as possible. We compare the three and we hope that the campaign we thought was suited to them performs better.

Researcher: ...Your team is gathering this information looking at the data, trying to make sense of what it means.

Executive B: Yes.

Researcher: And then at that point you will actually test potential or test particular marketing campaigns, see what the response is to the activity.

Executive B: Yes. ...What we try to do is each campaign we take about 80% of the campaign’s budget and apply it against what we have learned in the past. So that is kind of the 80% we know we are going to generate return on it and then we take 20% to test new things.

By turning 20% of their marketing budget towards experimental practice, this particular executive and his team was able to take a cumulative perspective on the knowledge they had gained, both in terms of understanding consumer behaviour and marketing effectiveness.

His experiences were replicated in another discussion with an executive who was just as pragmatic about creating knowledge about consumer behaviour and marketing:

Executive C: Before you decide to [attempt to gather consumer] knowledge just for the sake of knowledge, it all costs money, right? So you have to say “am I going to make a different business decision on where I am going or how I am going to invest my money?” before I go ahead and do it. I have learned a lot of this over the years.

Researcher: Through trial and error?

Executive C: Well, you go through that phase where you have the money [to gather general consumer knowledge] but now the budgets are tight and you have to be accountable. We always were accountable but there was more interest in knowledge when we first started. We had to come to understand what the program is [so we could] optimize this in terms of what we need and what we don’t need.

Both executive indicate how knowledge is something gained by optimizing the program and the learning from experience. By saying “I have learned a lot of this over the years,” this latter executive indicates that she is keenly aware of how the system is able to be used for “what we need.” Her knowledge and the knowledge of the former interviewee enable the possibility for the program to both increase profits and improve marketing effectiveness. While this may be seen as an aspect of ‘informational capitalism’ wherein the “action of knowledge upon knowledge itself” is the main source of productivity (see Castells 1996:17), it is also is indicative of the reflexive positioning program executives and their team members take toward their work. They are accountable for their work, but they are also employed for their knowledge of the system and what it can and cannot produce in terms of profitability.

As is clear in these comments from executive A, knowledge of the system and its abilities is essential for making sense of the information loyalty programs produce:

What it boils down to every time is how the information—the raw information sitting in the system—is regrouped, calculated, processed so that we can draw some conclusions about transactional behaviour. This leads ultimately to how one would segment [consumers]. If you have the wrong definitions or the wrong view of the [consumer’s] world, then your segments are going to be wrong, right? We have to get a stake in the ground as to what all those basic variables are. What does that mean? What are the kind of things that we need to understand? I’m not just going to add on information for the sake of information, psychographic—demographic whatever, because we have to understand the basic structure, [especially of]...what the data marriage with peoples’ brains creates. I think that that’s a challenge for companies to manage ...[which is fine] as long as those individuals stay in those jobs really long time and understand that definite level and all that stuff. Then you have got the same continuity of learning and knowledge.

The use of these terms, of the ‘ground’, of ‘variables’, and of ‘structure’, combined with a marriage metaphor between brains and data, and a final emphasis on the continuity of learning depicts well the struggle of the reinvented manager within soft capitalism. She must “somehow find the means to steer a course in this fundamentally uncertain world”, doing so in a way that cultivates openness, flexibility, and possibilities for continual learning (Thrift 2005: 43).

Part of finding this course is reliant on research—on connecting what is evident in data with an appropriate interpretation of that data. When asked how she learned to interpret consumer response toward a particular marketing campaign, another interviewee, executive D, responded this way:

We do actual research—I mean we go out with the focus groups and do surveys, lots of surveys. It is not just me saying ‘Oh I have a bad feeling with this reward’. We do research that can be quantitated [sic]. But I think that experience still needs to be overlaid with research. ...We use the research but we need to apply it with our experience.

This suggests that the intuition—the feeling—of the program director about a particular strategy, in this case a program marketing incentive, must be integrated with what is made evident in quantifiable data. It connects the so called ‘hard’ data that is program generated, to survey data, to focus group data, to recorded anecdotes from calls and letters by means of the history and experiences of loyalty program practitioners. “The aim is to produce an emergent ‘evolutionary’ or ‘learning’ strategy which is ‘necessarily incremental and adaptive, but that does not in any way imply that its evolution cannot be, or should not be analysed, managed, and controlled’” (Kay 1993: 359 quoted in Thrift 2005:43). This is a pragmatic and measured approach to loyalty programs, acting on what is known—the tacit knowledge of the workforce—and allowing for innovation and new customer knowledge production through a system of continual learning.

Loyalty programs are seen as successful by their practitioners based on how well a connection is made between an intimate knowledge of the business—the production and gathering of data and its meaning—and an intimate knowledge of consumers, specifically in terms of their digital representation and the associated meanings. The ability to make such connections on the part of those involved in the deployment of loyalty programs is reliant upon experiences built into a tacit knowledge of the program. While the tacit knowledge of the program practitioners is an essential element in the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing, it both is fed from and feeds into a ‘relational’ framework between corporations and consumers. To understand how this tacit knowledge is developed and applied in loyalty program marketing, it is best not to focus “only on producers or consumers but on the ‘relational work’ that occurs between them” (duGay 2004:100). The relational work is done by these program executives and their teams, and they focus on perfecting this relationship by learning from past processes, through ‘learning by doing.’ Data gathering and consumer profiling are subject to continual revisions based on experimental evaluations.

Application: data profiles and learning by doing

Consumer data and the interpretation of data is central for contemporary marketing. Consumer data can generally be divided into four broad yet often overlapping categories (see Michman 1991; also cited in Elmer 2004). First, geographic data are used to describe a given region and includes population density, climate, and geographic features within a specific market area. These are demarcated by telephone area codes, postal codes, internet urls and domain names. This base information is always connected with specific and unique demographic information on consumers. This second set of demographic data includes basic personal information such as name, age, sex, marital status, income, education, race/ethnicity, and occupation. A third set of data, psychographic data, connects the first two ‘geodemographic’ forms of data to more social aspects of consumers in terms of class, values, lifestyle, life stages, and personality. Last, these data are connected to the consumer’s previous interactions with the company. Consumer behaviour data includes frequency of patronage, brand loyalty, product preferences, product knowledge and marketing responsiveness. In large measure, loyalty programs provide a very detailed picture of this consumer behaviour data, although to differing degrees geographic, demographic and psychographic data are gathered from the initial information for participation in the program, as well as subsequent interactions with these consumers.

These different ‘layers’ of data are significant for understanding consumers, and adding additional data, such as available from third parties (i.e. census bureaus, data brokers) allows corporations, as another executive suggests, to “get a little more colour around that particular member at present.” Executive E continues:

[W]hat we have is information that you volunteer as an individual. We have information that looks at your behaviour at any given time. We look at what you buy, and what you don’t buy. This behavioural information is used in what we call third party overlays. So with those two pieces of information you can start to see a lot of who that customer is and what they do. What third party data provides you is little bit more enriched view of that particular member so we can start to get things like ‘attitudes’.

This enriched view and the notion of ‘attitudes’ is important. An enriched view allows these program executives to begin to surmise the ‘why’ of consumer behaviour. Putting third party ‘overlays’ upon proprietary internal data from the loyalty program serves to fill in or enhance what is unknown or unclear about consumers, specifically motivations or ‘attitudes’ behind consumption practices (see Evans 2005).

The value in appending internal data with external data is that this layered data creates usable consumer information—information seen to enhance the potential for corporations to establish relationships with consumers. This mixture of data serves to help corporations create profiles, “a model or figure that organises multiple sources of information to scan for matching or exceptional cases, and is able to target individuals for specialized messages” (Lury 2004:133). Profiles are predicated on interconnections between these layers of data and serve to determine marketing practice. They are the means by which corporations engage in micro-marketing, one-to-one marketing and the customization of products. By focusing on narrower bands of consumers, on profiles that fit certain expectations, these corporations can subsequently decrease marketing costs and increase response rates.

Again loyalty programs offer a “robust source of behavioural data” and allow for the capture of “detailed transactional and preference customer data”(Lacey and Sneath 2006: 461). Data produced through loyalty programs allow consumers to be rendered as ‘known’, serving as a significant tool that provides for “unique opportunities to track an individual” in the form of these consumer profiles (Smith and Sparks 2003). As suggested above, the usefulness of data about consumers and the development of these profiles are intrinsically linked with the experiences and the tacit knowledge of those who are working with that data. To connect profiles with knowledge of marketing practice, consumer responsiveness is continually evaluated. This was made explicit in one interview (Executive F):

What you are going to see is that loyalty programs will continue to be really responsive to their users. This might mean they get rid of some stuff and they add some stuff or they come up with new ideas. They are always trying stuff. They are always testing things. ...They are constantly playing with it and measuring the consumer temperature versus what they are delivering. ...Loyalty programs are all very responsive consumer driven organizations because they are trying to modify consumer behaviour. They are quite sensitive to it.

This is a highly reflexive practice, as the connection between responsiveness to marketing and its effect on differing profiles of consumers—made clear by the desire to ‘modify’ consumer behaviour—are continually measured.

From the interviews conducted for this research, and as suggested by Thrift, the primary way to learn this connection is through ‘learning by doing.’ Most interviewees indicated that their work was based on some sort of “experiential learning” in which their teams built up an understanding of what was previously “uncertain and unknown” (Thrift 1997: 39). The programs have been and continue to be gradually shaped based on experiences with specific program successes and failures. Executive A asserted that loyalty program marketing is an industry in which companies can only learn through ‘trial and error’ and it is the knowledge gained through this trial and error that has to be passed on. She continued:

You can’t just press a button and say here is the data, or go to another company with that same data [and expect the same results]. They will look at it and all go, ‘Oh you’ve made a definition wrong’. ‘What definition’? Well it is around household size or whatever. This skews all your data. Then everyone is making decisions on the wrong thing. That’s my biggest fear in this whole area because it is absolutely critical that you get the right way, the right process, the right understanding of how our business works. The right data, you get the right individuals that know how to analyze the stuff and that they have had enough trial and error that they can go, “this didn’t work,” “that did work” and they can lead other people through it.

Here she reiterates the importance of experience and tacit knowledge, yet also hints at the cumulative nature of program knowledge, of people who have ‘enough trial and error’ behind them to be able to recognize and lead others in an analysis of data.

Trial and error is a continual process. Executive B’s description of this process was perhaps the most precise in explaining how this occurs:

We basically undertake a constant test-and-learn marketing application to [the] information [we process]. So we try discount offers, coupons, invitations to events, recognition or rewards where we are giving them a gift or a special experience. And we basically learn from every one of those. And we measure the impact of each of those activities, using experimental design basically with test and control groups. And then measure and say what’s the right investment in different customer groups, according to their value segmentation, their category orientation, in terms of which categories they purchase in, their frequency behaviour.

Though the degree to which interviewees articulated experiential learning varied, several strands in this quote are indicative of ongoing meaning-making in loyalty marketing practice. First, there is the indication of learning from every attempt to market to consumers—an accumulation of knowledge. This is gained through experiential learning, which is dependent upon impact measurements of marketing success as part of experimental marketing designs. This then feeds into a third strand of meaning-making discussed more fully below, revising marketing investments in different customer groupings based on consumer feedback. In the description above, the revision of these ‘investments’ are made in relation to the different categories of products with which this loyalty program is associated. However, other interviewees noted the revision of consumer groupings were made in relation to other significant factors such as life stages, life styles, income levels, and geographic location. Overall, in order to evaluate the effectiveness of these revisions and their importance for future data analysis, another important element in the cultural circuit of loyalty programs is deployed: mechanisms for consumer feedback.

Revision: gauging consumer feedback

One of the most important elements in the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing is the continual assessment of the program and of consumer experiences with the program. These assessments are done in a number of ways and add to the tacit knowledge held by program executives and team members. This becomes the basis for future changes in data profiling and marketing experiments. The stated goal for these assessments is clear, as executive G suggests:

Our major target is to continually enhance the [consumer’s] experience. [The program] has a number of benefits and we would like to continually improve upon those benefits and add more benefits to the program. That is to continually make the program more robust.

Enhancing experiences, adding benefits, and making the program ‘more robust’ leads to more participation, more engagement and a better ‘relationship’ with the consumer. This desire is indicative of the now ubiquitous concept of ‘relationship marketing’ which suggests that the better a corporation knows, understands, and engages its consumers by orienting its business practices toward them, the better it is able to meet the needs of those consumers and to create a “sustainable competitive advantage” (Narver and Slater 1990:20).

To ensure that ‘relationships’ were being developed, and that the loyalty programs were in fact ‘more robust,’ loyalty program executives indicate an almost universal reliance on consumer feedback mechanisms to evaluate the general health and status of their programs. While the response rates of consumers to particular marketing campaigns were seen as primary mechanisms to view the effectiveness of a program, several other processes were crucial in supplementing the ‘hard’ data embodied in response rates. Many of these methods for evaluation were detailed in one interview (executive H):

There are a few metrics that we have [for measuring consumer responses to the program]. One of the primary ones is our customer service index. It is a random cash register driven survey in which we print out a request on the customer’s receipt asking them to visit our website or call a number and answer certain questions. That is something that we track with [consumer] comments both in terms of a verbatim file of all consumer comments and rolled up qualitatively analyzed comments. That comes to the group of us as a gauge on what customers are saying about the program. In addition, we have done significant number of focus groups tied to the program, and we do online surveys, like e-mail surveys, gauging response to the program. We look really closely at those key metrics in the program, specifically participation rates and redemption rates that guide for us in what we consider to be customer satisfaction. We also do a Print Measurement Bureau study on which loyalty programs you are a member, which is again a high level indicator for us on how the program is performing.

As this suggests, evaluating consumer involvement with a loyalty program and their overall satisfaction with the program occurs through several means. Two of the key more robust and widely used means are surveys and focus groups. All of the programs interviewed for this research used these tools to understand and better market to consumers, as well as to more effectively evaluate the program’s performance.

Some surveys were done at set times for preset purposes, but other surveys and most focus groups were less prescribed, as was the case for this program (executive I):

We get a lot of input on [our brand]through ...surveys and we do ad-hoc focus groups or other types of research when we feel it is necessary. This depends on what we are researching at the time. It is usually [our]members we get together to ask about either a program change that might looming or to get their input on something that we are thinking about doing.

While both the tacit knowledge of the program executives and the cumulative experiences of trial and error learning do shape the development of loyalty programs, consumer input is crucial. Direct contact with consumers, from focus groups to surveys to anecdotal experiences with the program, significantly influence the direction of program marketing.

One of the programs purposely sought out consumers on an individualized basis (executive G):

We do our due diligence to see what we can do about what they would like to see in the program. ...We do our research to see if A. the benefit can be done and B. whether it makes sense economically speaking. This is again to resolve members’ concerns and to continue to enhance the program.

By most interviewee accounts, consumers are more than willing to respond to the enquiries of the loyalty programs as to the effectiveness and value of their program. Consumers were described as “vocal overall”, though program executives acknowledged they tended to hear more negative comments and criticisms about the programs. On the whole however, they are generally pleased with the number of responses received that were more general. A number of consumers were described as heavily invested in these programs and willing to respond to program enquiries with constructive comments.

In addition to surveys and focus groups, several of these programs have advisory panels that gather feedback from consumers. In one example members are asked to contribute to the consumer feedback loop four times a year (executive G).

There are 10,000 members that make up our panel and on that you would have a good cross section of [lower, middle, top] members. Every quarter we present them with an online survey and have them fill it out. The results are tabulated by a third party company that we work with and they evaluate the survey and the results and produces some findings for us to take action on.

Members of another advisory panel respond more frequently (executive B):

We have a group; we call it the Voices Advisory Panel. So we have 8000 customers that participate in the online panel on a weekly basis. Not all 8000 participate every week of course, but we basically talk to them on a regular basis. They are involved in the business—they participate in the business. They help us to make decisions. We ask them about advertising and saying ‘does this appeal to you? How would you improve it?’ We ask them about customer service experiences and what’s working or not working. We basically use them as a community of heavily engaged customers. They are—I would say—the closest thing we have to a brand community.

This ‘community,’ a group of consumers actively engaged and committed to evaluating and supporting a particular program, actively shape the direction and practices of these programs. Their feedback has become an important part of the ongoing learning and meaning-making for loyalty program marketing. Their comments, suggestions, and concerns are often the basis for new marketing strategies, as well as serve as interventions for planned or intended marketing campaigns.

This consumer feedback is crucial for loyalty program marketing. What might have been presumed to be a unidirectional process in which consumer data was gathered, analyzed, and projected on consumers by means of profiles is clearly a nuanced and relational process. The multiple means of feedback become a part of the tacit knowledge of program practitioners and affects the development and deployment of new marketing experiments. However, the use of this knowledge derived from marketing experiments can also define and identify consumers in particular ways, such that the constantly adjusting operations of these ‘informationally’ powerful programs can significantly affect the life chances and opportunities of consumers.

Consumers and the cultural circuit of loyalty programs

The cultural circuit of meaning-making in loyalty programs is important because profiles and categories and their continual revision frame the way in which consumers are understood and marketed to. For these programs, the accumulation of data made manageable through consumer profiles, and the accumulation of tacit knowledge and experiential learning are an attempt to stabilize what is otherwise an unpredictable, flexible and continually changing consumer culture (see Bauman 2001). Marketing practice, profiles and the “techniques of profiling are constantly being updated and are increasingly automated” (Lury 2004: 133) in order to produce nuanced ‘snapshots’ of consumers and the market with which a corporation intends to engage. While these snapshots are time sensitive and inherently malleable, they are also determinative of corporate understandings of consumer behaviour.

Tacit knowledge, its application, and its revision through loyalty program marketing occurs within a consumer culture that dominates modes of being in everyday life (see Slater 1997; and Bauman 2001). The abilities of consumers to modify and change systems of consumption—to cause the ‘continuous adjustments’ inherent in this cultural circuit—occur while their behaviours are simultaneously being interpreted by that same system. That is, on the one hand, marketing practices can be seen as disciplinary mechanisms that transform a heterogeneous mass of people into more homogeneous market segments. This allows consumers to be categorized, surveyed and targeted and, according to these interviews, their behaviours can be moved in statistically significant ways. On the other hand, people interact with these marketing techniques, responding in ways that express personal preferences, desires and needs that are then absorbed as new forms of knowledge by program practitioners. The homogeneous market segments are made more nuanced and dynamic, but they are made this way for the purposes of increasing corporate profits.

The irony is that the importance of the consumer, of her preferences, desires and needs, has tended to dominate contemporary descriptions of consumption. Given the growing informational power of corporations such as is acquired through loyalty programs, the notion that “the consumer is king and the corporation is at his or her mercy” is increasingly false (see Schor 2007:28). This is no longer a coherent way to describe the way in which consumers are understood, nor how they make their consumption decisions.

Arguing that consumers are in control over their life and that they can freely write their own stories appears too simplistic. Society and human beings are indeed too complex and too subtle to simply take a pure agentic approach to marketing (Cherrier and Murray 2004:510).

Though it is beyond the scope of this paper to detail the ways in which consumers can be seen to change their consumption in line with marketing practices (see for instance Pridmore 2008; Zwick and Dholakia 2004a; Stone et al. 2004; Dowling and Uncles 1997), the cultural circuit of loyalty marketing, while dependent upon consumer feedback and engagement, is able to shape the consumption practices of its members through the mechanics of these programs. There are of course a number of failures, of points in which marketing did not connect with its intended audience, yet each interviewee saw these as learning experiences. They were each proud of the way their program in general shifted groups of consumers toward particular patterns of behaviour—behaviour that was measurable and manageable.

It is important to be clear here. This does not mean to suggest that every individual consumer profile was or can be moved toward a ‘desired’ consumer behaviour. That is not the objective. These programs are continually modified to better connect with and engage their consumers in order to produce ‘desired’ (i.e. more profitable) results (see “Building Loyalty” 2006; Capizzi and Ferguson 2005; Reinartz and Kumar 2003; and Uncles et al. 2003). In the end, the program executives were satisfied to have significant portions of targeted profiles respond to different marketing campaigns. Even in this process, the successes and failures of these marketing campaigns in terms of response rates are made to form an essential part of the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing by feeding back into the tacit knowledge of program practitioners and their future marketing applications.

What this cultural circuit does is assist in “tracing the ways in which different sorts of consumer conducts are mobilised, motivated and distributed through specific commercial actions and devices” (duGay 2004:100). The constant adjustments of these programs, described here in terms of reflexive marketing, are not about determining the possible and actual actions and behaviours of consumers by determining “physical and social barriers and opportunities.” Instead this form of marketing is embedded in the “ways in which we conceptualize and realize who we are and what we may be” (Hacking 2004:287). These programs are set up to seek an evolving understanding of the connection of everyday life with program data.

As the anthropology of consumption has so clearly shown, classifying products, positioning them and evaluating them inevitably leads to the classification of the people attached to those goods. Consumption becomes both more rational (not that the consumer is more rational but because (distributed) cognition devices become infinitely richer, more sophisticated and reflexive) and more emotional (consumers are constantly referred to the construction of their social identity since their choices and preferences become objects of deliberation: the distinction of products and social distinction are part of the same movement) (Callon et al. 2002:212).

The rational and emotional consumption to which Callon, Méadel and Rabeharisioa refer is precisely what the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing seeks to understand. These programs are founded on the ‘convergence’ or fitting together of informational artefacts (i.e. data) and social worlds (i.e. consumer choices) (Bowker and Star 1999:82). In this context, there is a clear interplay between how consumers are profiled and how consumer behaviours and responses are integrated into marketing practice.

The cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing can be seen as a point in which technologies of identification come into contact with everyday practices: this is in part how consumers come to produce the social worlds they come to inhabit. The open-ended nature of this process means a continual reshaping of these technologies of identification, but it also means that consumers are subject to the consumption behaviours they engage in and express. They help to produce socio-economic and cultural expectations that become codified and embedded in the program technologies, part of the tacit knowledge of program practitioners and crucial factors in the modifications and adjustments made to the consumer profiles and categories to which they are subject.

Conclusion

At the heart of the cultural circuit of loyalty programs is something not yet suggested in this paper. Following Andrew Smith and Leigh Sparks, one can begin to see how these dynamic processes indicate that “the development of loyalty schemes and associated technology and software has transformed basic market research into an ongoing consumer surveillance system” (2003). Jennifer Rowley reaches the same conclusion about this knowledge accumulation and its use:

As both businesses and public sector organisations improve their customer knowledge, management practices and competence, the threat of effective consumer surveillance escalates. Organisations may know more about us than we know about ourselves, and as individuals and societies we are ripe for manipulation. Marketing has always been about persuasion and customer data translated into information, and knowledge that drives definition and design of offerings and interactions lends large organisations even greater power (2005:109).

Rowley’s concern is certainly one that suggests the negative aspects of this form of surveillance, seeing it as a ‘threat.’ However surveillance itself is always Janus faced—there are always aspects of care and control (Lyon 2001). Suggesting this as a form of surveillance is also not meant to convey that this surveillance is all encompassing. Loyalty programs are part of an orientation to consumption that anticipates participation and rewards it. By participating in such programs consumers help to constitute themselves “as a known and knowable object upon which the marketer can now act strategically” (Zwick and Dholakia 2004b:32). These strategic actions most certainly carry benefits—as the program executives interviewed for this research are keen to convey—but they also raise concerns about the manipulation mentioned by Rowley and the significant potential for exclusion raised by others (see for instance Gandy 1993; Perri 6 2005).

This suggestion that surveillance is at the heart of the cultural circuit of loyalty programs raises several Foucauldian strands of argumentation that can be further explored. Within the panoptic like structure of this system, program participants can indeed be seen as “caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves bearers” (Foucault 1977: 201). Likewise, Foucault’s writing on governmentality (1991) taken up by Nicholas Rose and others can equally be seen as important here, as these programs are clearly focused on instrumentalizing the forces that mobilise consumer conduct “in order to shape actions, processes and outcomes in desired directions” (Rose 1999:4). Yet the tendency for these strands to focus more on overarching issues of control and power may obscure to some extent the contingent nature of this form of marketing. By focusing on the cultural circuit of loyalty program marketing, this paper attempted to highlight how loyalty programs are comprised of highly innovative and dynamic processes. There are a number of implications for consumers given this context, but this also points to questions about other practices of identification in other knowledge based enterprises and systems that serve to identify, profile and categorize persons. As contemporary mechanisms of identification, loyalty programs are part of a network of relations, both human and technological, that are continually modified and self-augmenting. It is important to recognize how such meaning-making occurs and is continually modified in order to understand the operation of these programs and their implications.

References

Bauman Z. Consuming life. J Consum Cult. 2001;1:9–29.

Bowker GC, Star SL. Sorting things out: classification and its consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1999.

“Building Loyalty.” 2006. Marketing. April 27. http://www.marketingmag.ca/workingknowledge/images/BuildingLoyaltyHandbook_Eng.pdf

Callon M, Méadel C, Rabeharisioa V. The economy of qualities. Econ Soc. 2002;31:194–217.

Castells M. The rise of the network society. Volume 1 of The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell; 1996.

Capizzi MT, Ferguson R. Loyalty trends for the twenty-first century. J Consum Market. 2005;22:72–80.

Cherrier H, Murray JB. The sociology of consumption: the hidden facet of marketing. J Market Manag. 2004;20:509–25.

Deighton J. Consumer identity motives in the information age. In: Ratneshwar S, Mick DG, editors. Inside consumption: consumer motives, goals and desires. London: Routledge; 2005.

Dowling GR, Uncles M. Do Customer Loyalty Programs Really Work? Sloan Manage Rev. 1997;38:71–82.

duGay P. Guest editor’s introduction. Consumpt Mark Cult. 2004;7:99–105.

Elmer G. Profiling machines. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2004.

Evans M. The data-informed marketing model and its social responsibility. In: Lace S, editor. The glass consumer. Bristol: The Policy Press; 2005.

Foucault M. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. London: A. Lane; 1977.

Foucault M. Governmentality. In: Burchell G, Gordon C, Miller P, editors. The Foucault effect. Hemel Hempstead: Wheatsheaf; 1991.

Gandy OH. The panoptic sort: a political economy of personal information. Boulder: Westview; 1993.

Hacking I. Between Michel Foucault and Erving Goffman: between discourse in the abstract and face-to-face interaction. Econ Soc. 2004;33:277–302.

Hart S, Smith A, Sparks L, Tzokas N. Are loyalty schemes a manifestation of relationship marketing? J Market Manag. 1999;15:541–62.

Lacey R, Sneath JZ. Customer loyalty programs: are they fair to consumers? J Consum Market. 2006;23:458–64.

Latour B. Science in action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1987.

Lury C. Brands: the logos of the global economy. London: Routledge; 2004.

Lyon D. Surveillance society: monitoring everyday life. Buckingham: Open University; 2001.

Michman RD. Lifestyle market segmentation. New York: Praeger; 1991.

Moor E. Branded spaces: the scope of ‘new marketing’. J Consum Cult. 2003;3:39–60.

Narver JC, Slater SF. The effect of market orientation on business profitability. J Market. 1990;54:20–35.

Perri 6. The personal information economy: trends and prospects for consumers. In: Lace S, editor. The glass consumer: life in a surveillance society. Bristol: The Policy Press; 2005.

Pridmore J. Loyal Subjects?: Consumer Surveillance in the Personal Information Economy. Ph.D. Dissertation . Department of Sociology, Queen’s University; 2008.

Reinartz W, Kumar V. The impact of customer relatioship characteristics on profitable lifetime duration. J Market. 2003;67:17–35.

Rose N. The powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

Rowley J. Customer knowledge management or consumer surveillance. Glob Bus Econ Rev. 2005;7:100–10.

Schor J. In defense of consumer critique: revisiting the consumption debates of the twentieth century. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2007;611:16–30.

Slater D. Consumer culture & modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1997.

Smith A, Sparks L. Making tracks: loyalty cards as consumer surveillance. Eur Adv Consum Res. 2003;6:368–73.

Stone M, Bearman D, Butscher SA, Gilbert D, Crick P, Moffett T. The effect of retail customer loyalty schemes—Detailed measurement or transforming marketing? J Target Meas Anal Market. 2004;12:305–18.

Thrift NJ. The rise of soft capitalism. Cultural Values. 1997;1:29–57.

Thrift NJ. Knowing capitalism. London: Sage Publications; 2005.

Uncles MD, Dowling GR, Hammond K. Customer loyalty and customer loyalty programs. J Consum Market. 2003;20:294–316.

Zwick D, Dholakia N. Consumer subjectivity in the Age of Internet: the radical concept of marketing control through customer relationship management. Inf Organ. 2004a;14:211–36.

Zwick D, Dholakia N. Whose identity is it anyway? Consumer representation in the age of database marketing. J Macromarket. 2004b;24:31–43.

Zukin S, Maguire JS. Consumers and consumption. Annu Rev Sociol. 2004;30:173–97.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pridmore, J. Reflexive marketing: the cultural circuit of loyalty programs. IDIS 3, 565–581 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12394-010-0064-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12394-010-0064-9