Abstract

This study aimed at investigating the prevalence and factors associated with living alone among older persons in Uganda. A secondary analysis of the 2010 Uganda National Household Survey (UNHS) data was conducted. A complementary log-log regression model was used to estimate the association between living alone and demographic, socio-economic and health factors. Nearly one out of ten (9%) older persons lived alone in Uganda. Living alone was associated with being divorced / separated (OR 18.5, 95% CI: 10.3–33.3), being widowed (OR 8.8, 95% CI: 5.1–15.2), advanced age (OR 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4–3.2), residence in western region (OR 0.6, 95% CI: 0.3–0.93), poor wealth status (OR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.2–06), receiving remittances (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.3) and being disabled (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2–2.1). Living alone among older persons did not vary by gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing has become a global concern in the past two decades (Beard et al. 2015). Improvement in the health care systems, decreased fertility rates and reduction in child mortality have contributed to the phenomenon (Bloom 2011; Cai 2010). There is a remarkable variation across continents, regions and countries with Western countries contributing to the majority of the older population (Guzman et al. 2012).

Worldwide, the proportion of older persons (aged 60 years and above) stands at 11% and it’s anticipated to double by 2050 (UNDESA 2013). In sub-Saharan Africa, older persons comprise 5% of the population (UNFPA 2012). In Uganda, the current population of older persons is estimated at 1.6 million (5% of the population) and it is expected to increase to 5.5 million in 2050 (UBOS and ICF International 2012).

Living arrangements is a critical issue in the discourse on population ageing. Living arrangements depict familial and non-familial relationships with whom the older persons share / reside in the same household (Victor 2005). Living arrangements provide immediate and adjacent social care and support to frail older persons (Moen and Wethington 1992). Living alone is where an older person lives alone in a household.

In the past two centuries, patterns of living arrangements among older persons in the western world have drastically changed (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002). Trends of older persons living alone have steadily increased (Hays and George 2002; Kramarow 1995; Zsembik 1993). Studies have documented that improvement in the housing structure (Schafer 1999), need for privacy in later years (Portacolone and Halpern 2014), departure of adult children due to marriages, widowhood and divorces are associated with living alone in later years (Gibler et al. 1998; Kim and Rhee 1997; Wolf 1995). For example in Japan, 15% of older persons were living alone in 2005 (NIA 2017). In Norway, most of the older persons lived in single households (Tomstad et al. 2012).

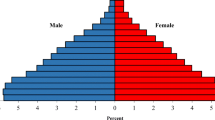

The proportion of older persons living alone varies from continent to another. A comparative study of living arrangements among older persons indicated that the percentage of those living alone was higher in Africa (2%) than in Asia (1%) and Latin America (1.4%). Among those age 65+, the percentage living alone was higher in Africa (9.7%) compared to Asia (7.3%) and Latin America (8.4%). Generally, the prevalence of older women living alone was higher than that of older men in the three continents (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002).

Living alone poses a high risk of poor health conditions and outcomes among older persons (Cornwell and Waite 2009; Haslbeck et al. 2012; Magaziner et al. 1988). Most studies have documented that living alone leads to poor psychological wellbeing (Dykstra 2009; Lim and Kua 2011; Millan-Calenti et al. 2013), depression (Mui 1999; Russell and Taylor 2009), higher mortality (Iecovich et al. 2011) and loneliness (Nzabona et al. 2015) among older persons.

In addition, living alone threatens the financial and social wellbeing of older persons in later years (Sereny 2011; Wandera et al. 2015b; Zimmer 2005). For instance, in Uganda, the social security scheme for older persons is partially developed, selected districts receive unconditional cash transfers (MoGLSD 2009, 2011). Currently, Uganda is implementing the social assistance grants for empowerment (SAGE grant) where some older persons (age 65 and older), receive an equivalent of $8 per month. However, this scheme is only operational in about 14 out of 112 districts in Uganda (MoGLSD 2009, 2011). Therefore, families and kinships are primarily responsible for supporting older persons in their later years (Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal 2014). Due to the relevance of the family in social support, it is imperative to investigate factors associated with living alone among older people.

Factors Associated with Living Alone

Generally, factors associated with living alone among older persons include being very old, being female, urban residence, lower socio-economic groups, not having a partner, poor health, or living without a child nearby (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Hosegood and Timæus 2005; Isherwood et al. 2012; Lawton et al. 1984; Nahemow 1979; Nzabona et al. 2015; Peek et al. 1997). Higher socio-economic status was associated with living alone in China (Sereny 2011).

In addition, the HIV/AIDS pandemic has virtually left most of the older persons to reside alone or with grandchildren due to loss of their adult children (Seeley et al. 2010; Seeley et al. 2009; Ssengonzi 2009). In addition, being childless (Schroder-Butterfill and Kreager 2005), having adult daughters leaving the household due to marriage and participation in labor force (Qin et al. 2008), formation of nucleated family, modernization and erosion of traditional social cohesion (Agree et al. 2005) have also been associated with living alone among older persons in later years.

Studies on living arrangements among older persons have majorly focused on East and south East Asia (Chaudhuri and Roy 2009; Chen et al. 2016). Some studies have focused on Latin America (de Vos 2000) and very few on Africa (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002). The study on Africa included Uganda and used the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS) data of 1990–1998.

In Uganda, few studies have addressed loneliness (Nahemow 1979; Nzabona et al. 2015), social isolation (Nahemow 1979; Richards 1966) and living arrangements of older persons. Some of these studies used small samples of older people among the Baganda tribe (Bennett and Mugalula-Mukiibi 1967; Nahemow 1979; Richards 1966). One of the Ugandan studies on living alone was among the Ganda community but had limited focus on older people (Bennett and Mugalula-Mukiibi 1967). The recent study on loneliness covered a sample of 605 older people, and did not conduct a gender-disaggregated analysis (Nzabona et al. 2015). Therefore, this paper aimed at investigating the prevalence and factors associated with living alone among older persons in using a nationally representative sample (n = 2382) of older persons in Uganda.

Methods

Data Source

We used the 2010 Uganda National Household Survey (UNHS) data, with permission from Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). The UNHS employed a two-stage stratified sampling. At the first stage, 712 enumeration areas were drawn using a probability proportionate to size. The second phase, all households were selected using systematic sampling. About 6800 households were interviewed in the survey. Detailed sampling procedures are reported elsewhere (UBOS 2010).

In this paper, older persons were defined as those aged 50 years and above. This definition is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for African countries (WHO 2015). Several “Studies on Adult health and Ageing” (SAGE) and INDEPTH network have used age 50+ to define older persons (Gómez-Olivé et al. 2010; Gómez-Olivé et al. 2013; Mwanyangala et al. 2010; Ng et al. 2010a; Ng et al. 2010b; Nyirenda et al. 2012) .

Outcome Variable

Studies on living arrangements of older persons use the household as a unit of analysis and the household composition (household listing) variable from census and survey data including the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Cheng and Siankam 2009; Yount and Khadr 2008). Household composition includes information about household members living in the household. The most commonly used coding categories for living arrangements among older people include living alone, living with a partner and living with others. For example, co-residence with adult children (Nguyen and Shibusawa 2013; Ugargol et al. 2016).

In this paper, living alone was the outcome variable. In the 2010 UNHS, respondents were asked to list all the household members in the last 12 months (including the guests) in the household roster. This was used to derive the outcome variable dichotomized as (0 – living with 1 or more people and 1 – living alone). In Uganda, a household is defined as people who live (sleep) and eat together (UBOS 2010).

Explanatory Variables

Demographic factors included; gender (male or female), age group (50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80+) and region (1-Central, 2-Eastern, 3-Nothern and 4-Western). Others included; place of residence (rural or urban), and marital status (1-Married, 2-separated or divorced or never married, and 3-widowed).

In addition, respondents were asked to specify the relationship of each household member to the household head. Different relationships included: head, spouse, son/daughter, grandchild, step child, parent of head or spouse, sister/brother of head or spouse, nephew/niece, other relatives, servant, non-relative, others) (UBOS 2010). In this paper, all relationships excluding household head and being a spouse were coded as relatives.

Socio-economic factors included; level of education, household poverty status, and household major source of earnings. The level of education was coded as: no education, primary, secondary and tertiary education. Household poverty was generated from household expenditures and recoded (1-poor, if the household spent less than a $1 a day and 0-not poor, if a household spent greater than a $1 a day). The households’ major sources of income were recoded as farming, wages, and remittances. These have been described elsewhere (Wandera et al. 2015a; Wandera et al. 2015b; Wandera et al. 2014).

Health related information was collected on illness in the last 30 days prior the survey. Ill health was binary variable (0-not sick, 1-sick). Disability was measured by asking six questions including difficulties in seeing, walking, hearing, communicating, concentrating or remembering and self-care. Disability status was generated from these six indicators using the UN Washington Group meeting on disability statistics. An older person was coded as disabled when they reported a lot of difficulty or could not function on any one of the six indicators. In addition, reporting some difficulty on at least two indicators was coded as being disabled.

In addition, self-reported NCDs were subjectively asked among older people. In the UNHS survey, respondents were asked to report whether they had any one of the three NCDs: hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease. The question allowed multiple responses to these three health conditions. These responses were coded as binary (0 = did not report any NCDs and 1 = reported at least one of the three NCDs. Thus, self-reported NCDs meant the reporting of diabetes, heart disease and hypertension, recoded as binary variable.

Statistical Analysis

We used the Pearson chi-square tests to identify initial bivariate associations and multivariable complementary log-log regression to estimate factors associated with living alone. The complementary log-regression model is recommended for rare outcomes (9% of older persons living alone) or when data is symmetrical and the outcome is binary (Long 1997; Penman and Johnson 2009). All the analyses were stratified by gender. We included variables that were significantly (p = 0.05) associated with living alone among all older persons. We used Stata version 13 to analyze the data. The survey was weighed to account for the complex survey design.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of Older Persons in Uganda

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of older persons in Uganda. Majority were women (57%) and of age 50–59 years (45%). Eastern region had a slightly higher (31%) distribution than other regions and over 90% of the older persons resided in the rural areas. More than half (59%) of older people were married.

Nearly three quarters (70%) had no formal education and more than three quarters (77%) spent more than one dollar a day. Six in ten (61%) of the older persons depended on farming as the major source of household earnings.

About 6 in 10 older persons reported illness or injury in the past 30 days and a third (33%) were disabled. Similarly, near a quarter (23%) reported at least one of the non-communicable diseases including diabetes, heart disease and hypertension.

Association between Living Alone and Selected Demographic and Socio-Economic Factors

Table 2 presents the association between living alone and demographic and socio-economic factors. Among these variables, gender, place of residence, educational level, and self-reported NCDs were not associated with living alone among older people in Uganda. However, age, region of residence, marital status, poverty status, major source of household earnings, ill health and disability status, were associated with living alone among older people in Uganda.

The prevalence of living alone was higher among older people with advanced age (70–79+), residing in central region, and those who were divorced or separated. In addition, living alone was also high among older persons who were disabled, depended on remittances, and reported ill health in the last 30 days.

Multivariable Results

Table 3 shows the results of multivariable complementary log-log regression of factors associated with living alone among older persons in Uganda.

The odds of living alone increased with age (70–79) among older women and not for older men. There were no differences in living alone among all older persons aged 50–59 and 80+ years. Advancement in age was not associated with living alone among older men. However, older age was associated with living alone among women.

Older persons from western compared to central region were less likely to live alone. This was the same pattern for older men. For older women, those from northern region were more likely to live alone compared to those from central region.

Separated, divorced, and widowed older persons had increased odds of living alone. The same pattern was observed for both older men and women.

Older persons who were poor had reduced odds of living alone. The same pattern was observed for men, women and all older persons. Older people who depended on remittances were more likely to be living alone than those who depended on farming. Older men who earned wages were more likely to live alone compared to those who depended on farming.

In addition, women and all older people who reported a disability had increased odds of living alone. However, disability status was not associated with living alone among older men only.

Discussion

The prevalence of living alone among older persons in Uganda was 9%. This is about the same level as that of 23 selected African countries including Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda among others (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002). Although in the developing countries, the phenomena of living alone is uncommon, the structure of living arrangement is starting to shift and this is expected to change in the next two decades (Bloom 2011; Eastwood and Lipton 2011). This is higher than the prevalence of living alone in other developing countries like India (Ugargol et al. 2016) and lower than that (over 50%) reported in China (Nguyen and Shibusawa 2013).

The factors which were strongly associated with living alone were marital status and being poor (negative association). Others included age, region of residence, source of household earnings, being disabled but not ill health in the last 30 days.

Marital status had the strongest association with living alone among older persons. Separated, divorced or widowed older persons had increased odds of living alone in Uganda. This confirms the findings in a Ugandan study (Nzabona et al. 2015) and elsewhere (Lawton et al. 1984; Mba 2002, 2007). The bivariate results (Table 2) indicated that more divorced / separated men (53%) than women (19%) were living alone. Older women usually care for orphans as result of HIV (Seeley et al. 2010; Seeley et al. 2009).

Low socio-economic status or poverty decreased the odds of living alone. Poor older persons (who spent less than a dollar per day) were less likely to live alone. In other words, those in better socio-economic status were more likely to live alone. This resonates with the study in China where older persons who were in a better socio-economic status preferred to live independently (Sereny 2011). In addition, those who depended on remittances were more likely to be living alone. Older persons who receive regular remittances are economically empowered and therefore, are more likely to live alone in (Hosegood and Timæus 2005). Generally, the need for social protection among older persons influences co-residence with adult children in later life (Lloyd-Sherlock 2001, 2002; Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal 2014). In Uganda, poverty is common among older persons and their vulnerability creates inequitable access to services (Golaz and Rutaremwa 2011). Since over 70% of older person had informal education and most of them depended on farming, their income is quite low hence increasing their vulnerability to poverty. A study in Uganda indicated that absence of pension benefits was associated with loneliness among older persons (Nzabona et al. 2015).

Advancement in age (70–79) increased the risk of living alone in Uganda. Increment in age reduces physical abilities and health status, which necessitate the need for assistance through co-residence (Liang et al. 2005; Wandera et al. 2015a). Wandera et al. highlighted the risk of disability; non-communicable diseases with poor health outcomes were more common among the oldest old (Wandera et al. 2015b; Wandera et al. 2014). Living alone could be associated with stigma or HIV/AIDS epidemic which leave older persons without relatives to co-reside with (Seeley et al. 2009). This was a bigger issue for older women than older men. Older women were at a higher risk of living alone because of advanced age. Women have a higher life expectancy and are more likely to be widowed with advancement in age compared to older men.

Region of residence was associated with living alone among older persons in Uganda. Older persons in western region were less likely to live alone compared to those in central Uganda. Similarly, older men were less likely to live alone in western region compared to western region. The possible explanation is the communal culture in western Uganda since some are pastoralists for example the Banyankole. On the other hand, central Uganda includes Kampala, which is a capital city and other neighboring towns. Older persons in urban areas face a higher risk of being isolated and living alone (Bennett and Mugalula-Mukiibi 1967; Nzabona et al. 2015). Another explanation for older people in central Uganda living alone more than other regions, is the cultural issue. In central Uganda, adult children prefer to establish homes away from their parents in order to be independent (Nahemow 1979; Richards 1966). Among older women only, those in northern region were more likely to live alone compared to those in central region. This resonates with the effect of the 20 years’ civil war in the region, which left many men dead and increase widowhood among them (Annan et al. 2011).

Disabled older persons were more likely to live alone compared to those who were not. Disability and old age are highly stigmatizing experiences associated with a high degree of vulnerability (Golaz and Rutaremwa 2011) and call for assistance in form of co-residence from kins (Stinner et al. 1990). It is common to find older persons who are isolated and living alone and assumed to be “witches” by the community around (Nzabona et al. 2015). A study in India also found that disabled older persons were more likely to live alone as result of social isolation and deprivation from the family (Ugargol et al. 2016). Similar findings were reported in china (Nguyen and Shibusawa 2013). In addition, the strains and burden of caring for disabled older persons are high on the care givers as postulated in the “privacy model” (Stinner et al. 1990; Ugargol et al. 2016) and therefore, family members could avoid them for such a reason.

Gender plays a crucial role in older persons’ living arrangements. Older women are reported to live alone more than older men do elsewhere (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Chaudhuri and Roy 2009; Peek et al. 1997; Yount and Khadr 2008). However, for this study, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of living alone between older men (10% vs 8%) and women (Table 2). This contradicts with findings in other studies that report older men living alone more than older women (Isherwood et al. 2012). A study in the US reported that older women lived alone more than older men since the former had more connections with adult children than the later (Gaymu and Springer 2010). The possible explanation is that older women are more likely to live with grandchildren as care givers in the context of HIV and AIDS (Seeley et al. 2010; Seeley et al. 2009; UNDESA 2005). On the other hand, older men are more likely to remarry after widowhood, separation and divorce (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Silverstein et al. 2006; Utz et al. 2002). In addition, it is a possibility that cultural factors or social desirability could have influenced women’s under reporting of living alone. In Uganda, women who live alone are considered as “social misfits” in society.

Ill health or being sick in the last 30 days was not associated with living alone. Some study in Uganda found that living alone was associated with poor health status (Nahemow 1979). The explanation was that people who are live alone / isolated or lonely tend to view their health status as bad (Cornwell and Waite 2009; Nahemow 1979). Thus poor self-rated health might be connected to social isolation. In the UNHS data, respondents were not asked to rate their health status. In future surveys, adding such questions would be relevant. In addition, older persons who fall ill can be taken for healthcare by their adult children (Zimmer 2005), who might be living in urban areas, where care is perceived to be better. Critical variables like the influence of Human Immuno-Deficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic were not captured in the UNHS and therefore, it was not possible to analyze them.

Strength and Limitations

The strength of this paper is that it contributes to knowledge about the prevalence, demographic, health and socio-economic factors associated with living alone among older persons using a nationally representative sample (2010 UNHS data) in Uganda. Household based surveys including the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) have been used in the study of older persons (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002). Notwithstanding the strength of the paper, several limitations merit discussion.

First, data from household surveys (including UNHS) has constraints in studying the living situations of older people. In the UNHS, data on the number of living children of older people who live outside the household was not collected. Thus, the proximity of children who don’t co-reside with older people is not known. The data cannot tell us who else was living in the proximity of the older persons. Also, exchanges between children and older people is not known (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002). However, in absence of national surveys on older people, such data are still useful in gleaning out living arrangements of older people.

Second, we used cross sectional data, which do not allow investigating patterns of living arrangements over time. They only provide statistics of living arrangements at a point time without critically analyzing how living alone vary with other variables over the years. Hence, investigation of causal factors contributing to living alone among older person is not feasible. However, the data provides the snapshot about the prevalence and gravity of the problem among the older persons in Uganda.

Third, the UNHS did not clearly depict the marital status of the adult children; this has an implication towards the co-residence with older persons. As per cultural consideration in Uganda, married couples leave their parents to co-reside with other partners. Hence, it was hard to ascertain whether the older persons were childless or had adult children who left the household due to other reasons.

Conclusions

In Uganda, living alone was associated with advanced age, living in central region, widowhood, marital separation and divorce, being in a better socio-economic status, depending on remittances and being disabled. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in living alone among older persons by gender.

Due to the vulnerability associated with living alone, there is a need to formulate policies and design programs that create formal community care centers for older persons who live alone and have no extended family support networks in Uganda. In most developing countries, governments and policy makers tend to value familial systems as source of protection for older persons in later years. However, the change in traditional social cohesion across generations points to a need to strengthen social support systems in later years.

There is a need to enact policies that address poverty and inequality among older persons in Uganda. Although, there is an on-going social assistance grants for empowerment (SAGE), which provides an equivalent of ten dollars to older persons per month, the target beneficiaries should be those who are living alone. The SAGE program targets selected 14 out of 112 districts in Uganda.

References

Agree, E. M., Biddlecom, A. E., & Valente, T. W. (2005). Intergenerational transfers of resources between older persons and extended kin in Taiwan and the Philippines. Population Studies, 59(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720500099454.

Annan, J., Blattman, C., Mazurana, D., & Carlson, K. (2011). Civil war, reintegration, and gender in northern Uganda. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(6), 877–908. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002711408013.

Beard, J. R., Officer, A., de Carvalho, I. A., Sadana, R., Pot, A. M., Michel, J.-P., Chatterji, S. (2015). The world report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4.

Bennett, F. J., & Mugalula-Mukiibi, A. (1967). An analysis of people living alone in a rural community in East Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 1(1), 97–115.

Bloom, D. E. (2011). 7 billion and counting. Science, 333(6042), 562–569. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209290.

Bongaarts, J., & Zimmer, Z. (2002). Living arrangements of older adults in the developing WorldAn analysis of demographic and health survey household surveys. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 57(3), S145–S157. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.3.S145.

Cai, F. (2010). Demographic transition, demographic dividend, and Lewis turning point in China. China Economic Journal, 3(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2010.511899.

Chaudhuri, A., & Roy, K. (2009). Gender Differences in Living Arrangements Among Older Persons in India. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 44(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909609102897.

Chen, T., Leeson, G. W., & Liu, C. (2016). Living arrangements and intergenerational monetary transfers of older Chinese. Ageing and Society, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16000623.

Cheng, S.-T., & Siankam, B. (2009). The impacts of the HIV/AIDS pandemic and socioeconomic development on the living arrangements of older persons in sub-Saharan Africa: A country-level analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 44(1), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9243-y.

Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103.

de Vos, S. (2000). Kinship ties and solitary living among unmarried elderly women in Chile and Mexico. Research on Aging, 22(3), 262–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027500223003.

Dykstra, P. (2009). Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing, 6(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3.

Eastwood, R., & Lipton, M. (2011). Demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa: How big will the economic dividend be? Population Studies, 65(1), 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2010.547946.

Gaymu, J., & Springer, S. (2010). Living conditions and life satisfaction of older Europeans living alone: A gender and cross-country analysis. Ageing & Society, 30(07), 1153–1175. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10000231.

Gibler, K. M., Moschis, G. P., & Lee, E. (1998). Planning to move to retirement housing. Financial Services Review, 7(4), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-0810(99)00024-4.

Golaz, V., & Rutaremwa, G. (2011). The vulnerability of older adults: What do census data say? An application to Uganda. African Population Studies, 26(1), 605–622.

Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Thorogood, M., Clark, B., Kahn, K., & Tollman, S. (2010). Assessing health and well-being among older people in rural South Africa. Global Health Action, 2, 23–35.

Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Thorogood, M., Clark, B., Kahn, K., & Tollman, S. (2013). Self-reported health and health care use in an ageing population in the Agincourt sub-district of rural South Africa. Global Health Action, 6, 19305. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.19305.

Guzman, J., Pawliczko, A., Beales, S., Till, C., & Voelcker, I. (2012). Ageing in the twenty-first century: A celebration and a challenge. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

Haslbeck, J. W., McCorkle, R., & Schaeffer, D. (2012). Chronic illness self-management while living alone in later life: A systematic integrative review. Research on Aging, 34(5), 507–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511429808.

Hays, J. C., & George, L. K. (2002). The life-course trajectory toward living alone: Racial differences. Research on Aging, 24(3), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027502243001.

Hosegood, V., & Timæus, I. M. (2005). The impact of adult mortality on the living arrangements of older people in rural South Africa. Ageing and Society, 25(3), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X0500365X.

Iecovich, E., Jacobs, J. M., & Stessman, J. (2011). Loneliness, social networks, and mortality: 18 years of follow-up. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 72(3), 243–263.

Isherwood, L. M., King, D. S., & Luszcz, M. A. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of social engagement in late-life widowhood. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 74(3), 211–229.

Kim, C.-S., & Rhee, K.-O. (1997). Variations in preferred living arrangements among Korean elderly parents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 12(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006503402430.

Kramarow, E. (1995). The elderly who live alone in the united states: Historical perspectives on household change. Demography, 32(3), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061684.

Lawton, M. P., Moss, M., & Kleban, M. H. (1984). Marital status, living arrangements, and the well-being of older people. Research on Aging, 6(3), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027584006003002.

Liang, J., Brown, J. W., Krause, N. M., Ofstedal, M. B., & Bennett, J. (2005). Health and living arrangements among older Americans does marriage matter? Journal of Aging and Health, 17(3), 305–335.

Lim, L. L., & Kua, E.-H. (2011). Living alone, loneliness, and psychological well-being of older persons in Singapore. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2011, 9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/673181.

Lloyd-Sherlock, P. (2001). Living arrangements of older persons and poverty. (Planes de vida de las personas mayores y pobreza). Population Bulletin of the United Nations (42–43), p. 18. https://www.popline.org/node/240698.

Lloyd-Sherlock, P. (2002). Social policy and population ageing: Challenges for north and south. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(4), 754–757. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.4.754.

Lloyd-Sherlock, P., & Agrawal, S. (2014). Pensions and the health of older people in South Africa: Is there an effect? Journal of Development Studies, 50(11), 1570–1586. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.936399.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables: Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Magaziner, J., Cadigan, D. A., Hebel, J. R., & Parry, R. E. (1988). Health and living arrangements among older women: Does living alone increase the risk of illness. Journal of Gerontology, 43(5), M127–M133. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/43.5.M127.

Mba, C. J. (2002). Determinants of living arrangements of Lesotho's elderly female population. Journal of International Women's Studies, 3(2), 22.

Mba, C. J. (2007). Gender disparities in living arrangements of older people in Ghana: Evidence from the 2003 Ghana demographic and health survey. Journal of International Women's Studies, 9(1), 153–166.

Millan-Calenti, J. C., Sanchez, A., Lorenzo-Lopez, L., Cao, R., & Maseda, A. (2013). Influence of social support on older adults with cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, or both coexisting. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 76(3), 199–214.

Moen, P., & Wethington, E. (1992). The concept of family adaptive strategies. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 233–251. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001313

MoGLSD. (2009). National Policy for older persons: Ageing with security and dignity. Kampala: Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development.

MoGLSD. (2011). Income security for all Ugandans in old age. Kampala: Ministry of Gender, Labor and Social Development.

Mui, A. C. (1999). Living alone and depression among older Chinese immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 30(3–4), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v30n03_12.

Mwanyangala, M. A., Mayombana, C., Urassa, H., Charles, J., Mahutanga, C., Abdullah, S., & Nathan, R. (2010). Health status and quality of life among older adults in rural Tanzania. Glob Health Action, 3(Supplement 2), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.2142.

Nahemow, N. (1979). Residence, kinship and social isolation among the aged Baganda. Journal of Marriage and Family, 41(1), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.2307/351741.

Ng, N., Hakimi, M., Byass, P., Wilopo, S., & Wall, S. (2010a). Health and quality of life among older rural people in Purworejo District, Indonesia. Global Health Action, 3 (Supplement 2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2957148/.

Ng, N., Kowal, P., Kahn, K., Naidoo, N., Abdullah, S., Bawah, A., ... Chatterji, S. (2010b). Health inequalities among older men and women in Africa and Asia: Evidence from eight health and demographic surveillance system sites in the INDEPTH WHO-SAGE study. Global Health Action, 3. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.5420. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20967141.

Nguyen, D., & Shibusawa, T. (2013). Gender, widowhood, and living arrangement among non-married Chinese elders in the United States. Ageing International, 38(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-011-9129-9.

NIA (2017). Global Ageing. National Institute of Ageing, National Institute of Health. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/global-aging. Accessed 12 Nov 2017.

Nyirenda, M., Chatterji, S., Falkingham, J., Mutevedzi, P., Hosegood, V., Evandrou, M.,. .. Newell, M. L. (2012). An investigation of factors associated with the health and well-being of HIV-infected or HIV-affected older people in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health, 12, 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-259.

Nzabona, A., Ntozi, J., & Rutaremwa, G. (2015). Loneliness among older persons in Uganda: Examining social, economic and demographic risk factors. Ageing and Society, 36(4), 860–888. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000112.

Peek, C. W., Henretta, J. C., Coward, R. T., Duncan, R. P., & Dougherty, M. C. (1997). Race and residence variation in living arrangements among unmarried older adults: Findings from a sample of Floridians. Research on Aging, 19(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027597191003.

Penman, A. D., & Johnson, W. D. (2009). Complementary log-log regression for the estimation of covariate-adjusted prevalence ratios in the analysis of data from cross-sectional studies. Biometrical Journal, 51(3), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.200800236.

Portacolone, E., & Halpern, J. (2014). “Move or suffer”: Is age-segregation the new norm for older Americans living alone? Journal of Applied Gerontology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814538118.

Qin, M., Punpuing, S., Guest, P., & Prasartkul, P. (2008). Labour migration and change in older people's living arrangements: The case of Kanchanaburi demographic surveillance system (KDSS), Thailand. Population, Space and Place, 14, 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.494.

Richards, A. I. (1966). The changing structure of a Ganda village: Kisozi, 1892–1952. Nairobi: East African Pub. House.

Russell, D., & Taylor, J. (2009). Living alone and depressive symptoms: The influence of gender, physical disability, and social support among Hispanic and non-Hispanic older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbn002.

Schafer, R. (1999). Determinants of the Living Arrangements of the Elderly. Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University. W99-6. http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/schafer_w99-6.pdf.

Schroder-Butterfill, E., & Kreager, P. (2005). Actual and childlessness in old age: Evidence and implications from east java, Indonesia. Population and Development Review, 31(1), 19–55.

Seeley, J., Wolff, B., Kabunga, E., Tumwekwase, G., & Grosskurth, H. (2009). This is where we buried our sons': People of advanced old age coping with the impact of the AIDS epidemic in a resource-poor setting in rural Uganda. Ageing and Society, 29(1), 115.

Seeley, J., Dercon, S., & Barnett, T. (2010). The effects of HIV/AIDS on rural communities in East Africa: A 20-year perspective. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(3), 329–335.

Sereny, M. (2011). Living arrangements of older adults in China: The interplay among preferences, realities, and health. Research on Aging, 33(2), 172–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027510392387.

Silverstein, M., Cong, Z., & Li, S. (2006). Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), S256–S266.

Ssengonzi, R. (2009). The impact of HIV/AIDS on the living arrangements and well-being of elderly caregivers in rural Uganda. AIDS Care, 21(3), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120802183461.

Stinner, W. F., Byun, Y., & Paita, L. (1990). Disability and living arrangements among elderly American men. Research on Aging, 12(3), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027590123004.

Tomstad, S. T., Soderhamn, U., Espnes, G. A., & Soderhamn, O. (2012). Living alone, receiving help, helplessness, and inactivity are strongly related to risk of undernutrition among older home-dwelling people. Int J Gen Med, 5, 231–240. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.s28507.

UBOS, & ICF International. (2012). Uganda demographic and health survey 2011. Kampala: Uganda UBOS & ICF International. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr264-dhs-final-reports.cfm.

UBOS. (2010). Uganda National Household Survey 2009–2010. Uganda Bureau of Statistics: Socio-economic module. Abridged report. Kampala.

Ugargol, A. P., Hutter, I., James, K. S., & Bailey, A. (2016). Care needs and caregivers: Associations and effects of living arrangements on caregiving to older adults in India. Ageing International, 41(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-016-9243-9.

UNDESA. (2005). Living arrangements of older persons around the world (Vol. 240). New York: United Nations.

UNDESA. (2013). World population prospects: The 2012 revision. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

UNFPA, H. (2012). Ageing in the twenty-first century: A celebration and a challenge. London and New York: United nations population fund (UNFPA), HelpAge International.

Utz, R. L., Carr, D., Nesse, R., & Wortman, C. B. (2002). The effect of widowhood on older Adults' social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. The Gerontologist, 42(4), 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.4.522.

Victor, C. (2005). The social context of ageing. New York: Routledge.

Wandera, S. O., Ntozi, J., & Kwagala, B. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of disability among older Ugandans: Evidence from the Uganda National Household Survey. Global Health Action, 7, 25686. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.25686.

Wandera, S. O., Kwagala, B., & Ntozi, J. (2015a). Determinants of access to healthcare by older persons in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0157-z.

Wandera, S. O., Kwagala, B., & Ntozi, J. (2015b). Prevalence and risk factors for self-reported non-communicable diseases among older Ugandans: A cross-sectional study. Global Health Action, 8, 27923. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.27923.

WHO. (2015). Definition of an older or elderly person: Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS project. Retrieved 07 march 2015, 2015, From http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/

Wolf, D. A. (1995). Changes in the living arrangements of older women: An international study. The Gerontologist, 35(6), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/35.6.724.

Yount, K. M., & Khadr, Z. (2008). Gender, social change, and living arrangements among older Egyptians during the 1990s. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-007-9060-7.

Zimmer, Z. (2005). Health and living arrangement transitions among China’s oldest-old. Research on Aging, 27(5), 526–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505277848.

Zsembik, B. A. (1993). Determinants of living alone among older Hispanics. Research on Aging, 15(4), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027593154005.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the mentorship of SOW by Professor Sally Findley of the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University at New York, USA. We would like to thank the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) for the permission to use and sharing of the Uganda National Household Survey (UNHS) data.

Funding

This research was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) (Grant No: 087547/Z/08/Z), the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No: B 8606.R02), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) (Grant No: 54,100,029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors Wandera, Ddumba, Akinyemi and Adedini, declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Treatment of Experimental Subjects (Animal and Human)

The authors used secondary data collected by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). The data were accessed during the data-sharing meeting by the UBOS at Makerere University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wandera, S.O., Ddumba, I., Akinyemi, J.O. et al. Living Alone among Older Persons in Uganda: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Ageing Int 42, 429–446 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-017-9305-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-017-9305-7