Abstract

We investigate the stability of measured risk attitudes over time, using a 13-year longitudinal sample of individuals in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979. We find that an individual’s risk aversion changes systematically in response to personal economic circumstances. Risk aversion increases with lengthening spells of employment and time out of labor force, and decreases with lengthening unemployment spells. However, the most important result is that the majority of the variation in risk aversion is due to changes in measured individual tastes over time and not to variation across individuals. These findings that measured risk preferences are endogenous and subject to substantial measurement errors suggest caution in interpreting coefficients in models relying on contemporaneous, one-time measures of risk preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and the Socioeconomic Panel (SOEP) also provide hypothetical lifetime income gamble questions. Several studies show that the measures of risk attitudes elicited from the traditional lottery-type survey questions are significantly related to several behaviors such as holding stocks, being self-employed, participating in sports, and smoking (Barsky et al. 1997; Dohmen et al. 2012). Such risky behavior can be alternative measures of risk attitudes.

For robustness, we also used a balanced panel data. As discussed below, the results are not sensitive to the use of a balanced panel data.

See Appendix 1 for full derivation of Eq. (1).

Marital status, fertility behavior, and education may be a consequence of risk preferences rather than a causal factor. However, none of our results are sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of these factors, and so we include them for completeness.

The exception is Barsky et al. (1997) who used a sample of 50–70 year-olds from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and found that risk aversion starts to decrease at age 60.

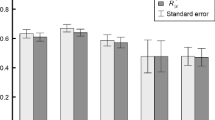

A further robustness check was undertaken by estimating the Eq. (3) over a 4-year time span. The result is reported in Appendix Table 7. Several economic variables lost the statistics’ significance based on the fixed effects model. The only statistically significant economic variable is employment duration. Nevertheless, we still conclude the same for the joint significance test—economic factors are still jointly significant (F 7,n-7 = 3, p = 0.004) while the individual demographics are not jointly significant (F 5,n-5 = 1.78, p > 0.1). The within variance also remains at 55%. The random effects estimation shows generally consistent results with those based on the 13 year time span.

Expanding the sample to include individuals with only partial information on demographic or economic variables does not change our conclusions. See Appendix Table 8.

References

Andersen S, Harrison GW, Lau MI (2008) Lost In State Space: Are Preferences Stable? Int Econ Rev 49(3):1091–1112

Anderson LR, Mellor JM (2009) Are risk preferences stable? Comparing an experimental measure with a validated survey-based measure. J Risk Uncertain 39(2):137–160

Baltagi BH, Song SH (2006) Unbalanced panel data: A survey. Stat Pap 47(4):493–523

Barseghyan L, Prince J, Teitelbaum JC (2011) Are Risk Preferences Stable across contexts? Evidence from Insurable Data. Am Econ Rev 101(2):591–631

Barsky RB, Juster FT, Kimball MS, Shapiro MD (1997) Preference Parameters and Behavioral Heterogeneity: An Experimental Approach in the Health and Retirement Study. Q J Econ 112(2):537–579

Bellemare MF, Brown ZS (2010) On The (Mis) Use of Wealth as a Proxy For Risk Aversion. Am J Agric Econ 92(1):273–282

Binswanger HP (1980) Attitudes toward Risk: Experimental Measurement in Rural India. Am J Agric Econ 62(3):395–407

Brown S, Dietrich M, Ortiz-Nuñez A, Taylor K (2011) Self-employment and attitudes towards risk: Timing and unobserved heterogeneity. J Econ Psychol 32(3):425–433

Chuang Y, Schechter L (2015) Stability of experimental and survey measures of risk, time, and social preferences: A review and some new results. J Dev Econ 117:151–170

Di Mauro C, Musumeci R (2011) Linking risk aversion and type of employment. J Socio-Econ 40(5):490–495

Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U (2012) The Intergenerational Transmission of Risk and Trust Attitudes. Rev Econ Stud 79(2):645–677

Donkers B, Melenberg B, Van Soest A (2001) Estimating risk attitudes using lotteries: A large sample approach. J Risk Uncertain 22(2):165–195

Drichoutis AC, Nayga RM (2013) Eliciting risk and time preferences under induced mood states. J Socio-Econ 45:18–27

Feinberg RM (1977) Risk Aversion, Risk, and the Duration of Unemployment. Rev Econ Stat 59(3):264–271

Gerrans P, Faff R, Hartnett N (2015) Individual financial risk tolerance and the global financial crisis. Account Finance 55(1):165–185

Guiso L, Paiella M (2008) Risk aversion, wealth, and background risk. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(6):1109–1150

Halek M, Eisenhauer JG (2001) Demography of Risk Aversion. J Risk Insur 68(1):1–24

Harrison GW, Johnson E, McInnes MM, Rutstrom EE (2005) Temporal stability of estimates of risk aversion. Appl Financ Econ Lett 1(1):31–35

Hartog J, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Jonker N (2002) Linking measured risk aversion to individual characteristics. Kyklos 55(1):3–26

Hoffmann AO, Post T, Pennings JM (2013) Individual investor perceptions and behavior during the financial crisis. J Bank Financ 37(1):60–74

Holt CA, Laury SK (2005) Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects: New Data without Order Effects. Am Econ Rev 95(3):902–904

Kimball MS, Sahm CR, Shapiro MD (2008) Imputing risk tolerance from survey responses. J Am Stat Assoc 103(483):1028–1038

Lerner JS, Keltner D (2000) Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognit Emot 14(4):473–493

Love RO, Robinson LJ (1984) An Empirical Analysis of The International Stability of Risk Preference. South J Agric Econ 16(1):159–165

Malmendier U, Nagel S (2011) Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk Taking? Q J Econ 126(1):373–416

Necker S, Ziegelmeyer M (2016) Household risk taking after the financial crisis. Q Rev Econ Finance 59:141–160

Nijman T, Verbeek M (1992) Nonresponse in panel data: The impact on estimates of a life cycle consumption function. J Appl Econ 7(3):243–257

Raghunathan R, Pham MT (1999) All Negative Moods Are Not Equal: Motivational Influences of Anxiety and Sadness on Decision Making. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 79(1):56–77

Riley WB, Chow KV (1992) Asset Allocation and Individual Risk Aversion. Financ Anal J 48(6):33–27

Roszkowski MJ, Cordell DM (2009) A longitudinal perspective on financial risk tolerance: rank-order and mean level stability. Int J Behav Account Finance 1(2):111–134

Sahm CR (2012) How Much Does Risk Tolerance Change? Q J Finance 2(4):1250020

Stephenson SP (1976) The Economics of Youth Job Search Behavior. Rev Econ Stat 58(1):106–111

Weber M, Weber EU, Nosić A (2013) Who takes risks when and why: Determinants of changes in investor risk taking. Rev Finance 17(3):847–883

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendices

Appendix 1

With n individuals in the sample and 4 temporally separated measures of risk aversion for each individual i, the total sum of square (TSS) is given by

where \( \overline{\theta}=\frac{1}{n}\sum \limits_{i=1}^n{\overline{\theta}}_{i0} \) and \( {\overline{\theta}}_{i0}=\frac{1}{4}\sum \limits_{t=1}^4{\theta}_{it} \).

Summing over the first t yields

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, I., Orazem, P.F. & Rosenblat, T. Are Risk Attitudes Fixed Factors or Fleeting Feelings?. J Labor Res 39, 127–149 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9262-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9262-2