Abstract

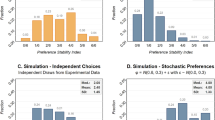

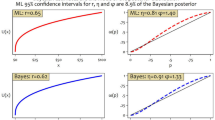

We examine the stability of risk preference within subjects by comparing measures obtained from two elicitation methods, an economics experiment with real monetary rewards and a survey with questions on hypothetical gambles. The survey questions have been validated by numerous empirical studies of investment, insurance demand, smoking and alcohol use, and recent studies have shown the experimental measure is associated with several real-world risky behaviors. For the majority of subjects, we find that risk preferences are not stable across elicitation methods. In interval regression models subjects’ risk preference classifications from survey questions on job-based gambles are not associated with risk preference estimates from the experiment. However, we find that risk classifications from inheritance-based gambles are significantly associated with the experimental measure. We identify some subjects for whom risk preference estimates are more strongly correlated across elicitation methods, suggesting that unobserved subject traits like comprehension or effort influence risk preference stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the first-price auction, a risk preference parameter is inferred from behavior using the bid function proposed by Cox et al. (1982).

In the BDM procedure, subjects state a selling price for a lottery they are endowed with. If the selling price exceeds a random number drawn by the experimenter, the subject plays the lottery and is awarded its proceeds; otherwise, the subject receives an amount equal to the random number and does not play the lottery. Given the parameters of the experiment and the stated selling prices, values of a risk preference parameter can be estimated for each subject from multiple rounds of the experiment.

In the Eckel and Grossman (2002) task, subjects make only one decision as opposed to ten.

In this task, each subject is presented with 12 “briefcases” containing cash payoffs ranging from $0.01 to $100. The subject is first given the choice of accepting $2.99 or selecting a case. If the subject selects a case, she is presented with a new offer that is a specific percentage of the average amount of money in the remaining cases. The task continues until the subject either accepts an offer or only two cases remain, at which point the subject selects one to eliminate and receives the contents of the remaining case. Risk aversion estimates are defined from the values of accepted and rejected offers.

In this regard, our study differs from Kruse and Thompson (2003) and Dohmen et al. (2005), which pair experiments with survey questions but use neither the Holt and Laury design nor the Barsky et al. (1997) survey questions. While not the main focus of the study, Deck et al. (2008) also administered a survey with the Barsky et al. (1997) survey questions after subjects completed the lottery choice task. Our study has several notable differences. We use a larger subject pool (236 subjects compared to 75) and the payoffs in our experiment are three times larger. We examine two series of survey questions on hypothetical gambles, define both 6-category ordinal measures and cardinal measures from the responses, and estimate interval regression models with the data.

The experiment was conducted using the Veconlab website designed by Charles Holt: http://veconlab.econ.virginia.edu/admin.htm.

Similarly, Harrison et al. (2007) excluded 14 subjects whose choices suggested they were confused or unmotivated.

These questions were included in the 2002 HRS. We are not aware of any studies that analyze responses to them.

These percentages are calculated as \( \left( {{{\left( {7 + 19} \right)} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{\left( {7 + 19} \right)} {198}}} \right.} {198}}} \right) * 100\% \), and \( \left( {{{\left( {8 + 37} \right)} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{\left( {8 + 37} \right)} {113}}} \right.} {113}}} \right) * 100\% \), respectively.

In Holt and Laury (2002), 13% of 212 subjects switched back to the safe option in an initial low-payoff treatment, and 7% switched back in a second low-payoff treatment.

Of the 236 subjects, 48% were female, 15% were nonwhite, 42% were freshmen, 21% sophomores, and 18% each were juniors and seniors. Students were asked to report their parents’ annual household income in seven possible categories. The three lowest categories (under $60,000) were combined as the omitted category in the regressions reported in Table 4, and 18% of students had parental income between $60,000 and $80,000, 19% between $80,001 and $100,000, 28% between $100,001 and $150,000, and 21% reported income greater than $150,000.

In the later case, we included an indicator variable for “don’t know” responses and re-coded the risk aversion category dummies from missing to zero for these cases. We also examined a sample that included the full 236 subjects, also including an indicator for the inconsistent responses and re-coding the risk aversion dummies from missing to zero. Results were not substantively different and the indicator for inconsistent responses had an insignificant negative coefficient.

Their procedures for generating the cardinal proxy involve mapping discrete responses from the survey questions into a continuous distribution and using maximum likelihood methods to estimate mean risk aversion for each of the discrete categories. These procedures are described in detail in Kimball et al. (2008). The Kimball et al. (2007) proxy data are available at http://www.umich.edu/~shapiro/data/risk_preference.

The coefficient on female is significant in some of our models of lottery choice behavior even after controlling for risk preference with the survey-based measures. This is consistent with previously reported findings. For example, Agnew et al. (2008) found that females were significantly more likely to choose a safe financial asset (an annuity) than a more risky (market-based) asset, even after controlling for the level of risk aversion using a lottery choice experiment. Combined, these results suggest that survey-based and experimental measures of risk aversion do not fully capture gender differences in risky decision making. While not the subject of this study, this is a fruitful area for research.

In a specification test, we used indicator variables for subject age in place of the dummies for academic year. Indicator variables were adopted because there was little variation in the ages of the subjects; more than 96% of our subjects were between the ages of 18 and 22. Indicator variables for 20 years, 21 years, 22 years and 23 years or more had insignificant coefficients, and the use of these controls had no effect on the coefficients of the response category indicators. Because missing data on age reduced our sample sizes by a few observations, we chose to report results with the academic year indicators in the tables.

A related finding is reported by Dave et al. (2007), who found that excluding subjects with lower math ability yielded similar estimates of predictive accuracy across two experimental elicitation methods.

References

Agnew, J. R., Anderson, L. R., Gerlach, J. R., & Szykman, L. R. (2008). Who chooses annuities? An experimental investigation of the role of gender, framing and defaults. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 98(2), 418–422.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2006). Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Experimental Economics, 9, 383–405.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2008). Lost in state space: are preferences stable? International Economic Review, 49(3), 1091–1112.

Anderson, L. R., & Mellor, J. M. (2008). Predicting health behaviors with an experimental measure of risk preference. Journal of Health Economics, 27(5), 1260–1274.

Barsky, R. B., Kimball, M., Juster, F. T., & Shapiro, M. (1997). Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: an experimental approach in the health and retirement study. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 537–579.

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M. H., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9, 226–232.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (2005). Risk preference instability across institutions: a dilemma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201(11), 4209–4214.

Brown, S. & Taylor, K. (2007). Education, risk preference, and wages. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, University of Sheffield.

Camerer, C. F., & Hogarth, R. M. (1999). The effects of financial incentives in experiments: a review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19(1–3), 7–42.

Charles, K. K., & Hurst, C. (2003). The correlation of wealth across generations. Journal of Political Economy, 111, 1155–1182.

Cox, J. C., Roberson, B., & Smith, V. L. (1982). Theory and behavior of single-object auctions. In V. L. Smith (Ed.), Research in experimental economics, volume 2. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc.

Dave, D., & Saffer, H. (2007). Risk tolerance and alcohol demand among adults and older adults, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Number 13482.

Dave, C., Eckel, C., Johnson, C., & Rojas, C. (2007). Eliciting risk preferences: when is simple better?” Working Paper, August.

Deck, C., Lee, J., Reyes, J. & Rosen, C. (2008). Measuring risk attitudes controlling for personality traits. Working Paper, June.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J. & Wagner, G. G. (2005). Individual risk attitudes: new evidence from a large, representative, experimentally-validated survey, IZA Discussion Paper No. 1730.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (2002). Sex differences and statistical stereotyping in attitudes toward financial risk. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(4), 281–295.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (2008). Sex and risk: experimental evidence. In C. Plott & V. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of experimental economics results, volume 1. New York: North-Holland Publishing.

Elston, J. A., Harrison, G. W. & Rutström, E. E. (2005). Characterizing the entrepreneur using field experiments, Working Paper, Max Planck Institute of Economics.

Harrison, G. W., Johnson, E., McInnes, M., & Rutström, E. E. (2005). Temporal stability of estimates of risk aversion. Applied Financial Economics Letters, 1, 31–35.

Harrison, G. W., List, J. A., & Towe, C. (2007). Naturally occurring preferences and exogenous laboratory experiments: a case study of risk aversion. Econometrica, 75(2), 433–458.

Hey, J. D., Morone, A., & Schmidt, U. (2007). Noise and bias in eliciting preferences, Kiel Working Paper Number 1386.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Isaac, R. M., & James, D. (2000). Just who are you calling risk averse? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 20(2), 177–187.

James, D. (2007). Stability of risk preference parameter estimate within the Becker-Degroot-Marschak procedure. Experimental Economics, 10, 123–141.

Kan, K. (2003). Residential mobility and job changes under uncertainty. Journal of Urban Economics, 54, 566–586.

Kimball, M. S., Sahm, C. R. & Shapiro, M. D. (2007). User’s guide for risk preference parameters. Available at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~shapiro/data/risk_preference/ImputationUsersGuideJASA.pdf; Accessed March 10, 2009.

Kimball, M. S., Sahm, C. R., & Shapiro, M. D. (2008). Imputing risk tolerance from survey responses. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(483), 1028–1038.

Kruse, J. B., & Thompson, M. A. (2003). Valuing low probability risk: survey and experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 50, 495–505.

Lahiri, K., & Song, J. G. (2000). The effect of smoking on health using a sequential self-selection model. Health Economics, 9, 491–511.

Lusardi, A. (1998). On the importance of the precautionary saving motive. American Economic Review, 88(2), 449–453.

Lusk, J. L., & Coble, K. H. (2005). Risk perceptions, risk preference, and acceptance of risky food. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(2), 393–405.

Picone, G., Sloan, F., & Taylor, D., Jr. (2004). Effects of risk and time preference and expected longevity on demand for medical tests. The Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 28(1), 39–53.

Rosen, H. S., & Wu, S. (2004). Portfolio choice and health status. Journal of Financial Economics, 72(3), 457–484.

Sahm, C. (2007). How much does risk tolerance change? Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Division of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board.

Schmidt, L. (2008). Risk preferences and the timing of marriage and childbearing. Demography, 45(2), 439–460.

Sloan, F. A., & Norton, E. C. (1997). Adverse selection, bequests, crowding out, and private demand for insurance: evidence from the market for long term care insurance. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 15(3), 210–219.

Spivey, C. (2007). Desperation or desire? The role of risk aversion in marriage,” Working Paper, Department of Economics, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

von Gaudecker, H.-M., van Soest, A., & Wengström, E. (2008). Selection and mode effects in risk preference elicitation experiments, IZA Discussion Paper Number 3321.

Weber, E. U., Blais, A.-R., & Betz, N. E. (2002). A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 263–290.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Schroeder Center for Healthcare Policy at the Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy at the College of William & Mary. The authors are grateful for valuable research assistance from Nathan Koch, Matthew Altamura, and Jennifer Kessler.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1. Lottery Choice Experiment Instructions

You will be making choices between two lotteries, such as those represented as “Option A” and “Option B” below. The money prizes are determined by the computer equivalent of throwing a ten-sided die. Each outcome, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, is equally likely. Thus if you choose Option A, you will have a 1 in 10 chance of earning $6.00 and a 9 in 10 chance of earning $4.80. Similarly, Option B offers a 1 in 10 chance of earning $11.55 and a 9 in 10 chance of earning $0.30.

Decision | Option A | Option B | Your Choice |

1st | $6.00 if the die is 1 | $11.55 if the die is 1 | A: or B: |

$4.80 if the die is 2–10 | $0.30 if the die is 2–10 |

-

Each row of the decision table contains a pair of choices between Option A and Option B.

-

You make your choice by clicking on the “A” or “B” buttons on the right. Only one option in each row can be selected, and you may change your decision as you wish.

-

Note: Try clicking on one of the circles and then change by clicking on the other one.

Decision | Option A | Option B | Your Choice |

1st | $6.00 if the die is 1 | $11.55 if the die is 1 | A: or B: |

$4.80 if the die is 2–10 | $0.30 if the die is 2–10 | ||

2nd | $6.00 if the die is 1–2 | $11.55 if the die is 1–2 | A: or B: |

$4.80 if the die is 3–10 | $0.30 if the die is 3–10 |

Even though you will make ten decisions, only one of these will end up being used. The selection of the one to be used depends on the “throw of the die” that is the determined by the computer's random number generator. No decision is any more likely to be used than any other, and you will not know in advance which one will be selected, so please think about each one carefully. This random selection of a decision fixes the row (i.e. the Decision) that will be used. For example, suppose that you make all ten decisions and the throw of the die is 9, then your choice, A or B, for decision 9 below would be used and the other decisions would not be used.

Decision | Option A | Option B | Your Choice |

9th | $6.00 if the die is 1–9 | $11.55 if the die is 1–9 | A: or B: |

$4.80 if the die is 10 | $0.30 if the die is 10 |

After the random die throw fixes the Decision row that will be used, we need to obtain a second random number that determines the earnings for the Option you chose for that row. In Decision 9 below, for example, a throw of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 will result in the higher payoff for the option you chose, and a throw of 10 will result in the lower payoff.

Decision | Option A | Option B | Your Choice |

9th | $6.00 if the die is 1–9 | $11.55 if the die is 1–9 | A: or B: |

$4.80 if the die is 10 | $0.30 if the die is 10 | ||

10th | $6.00 if the die is 1–10 | $11.55 if the die is 1–10 | A: or B: |

For decision 10, the random die throw will not be needed, since the choice is between amounts of money that are fixed: $6.00 for Option A and $11.55 for Option B.

-

Making Ten Decisions: After you finish these instructions, you will see a table with 10 decisions in 10 separate rows, and you choose by clicking on the buttons on the right, option A or option B, for each of the 10 rows. You may make these choices in any order and change them as much as you wish until you press the Submit button at the bottom.

-

The Relevant Decision: One of the rows is then selected at random, and the Option (A or B) that you chose in that row will be used to determine your earnings. Note: Please think about each decision carefully, since each row is equally likely to end up being the one that is used to determine payoffs.

-

Determining the Payoff for Each Round: After one of the decisions has been randomly selected, the computer will generate another random number that corresponds to the throw of a ten sided die. The number is equally likely to be 1, 2, 3, ... 10. This random number determines your earnings for the Option (A or B) that you previously selected for the decision being used.

-

Determining the Final Payoff: There will be 2 rounds, and therefore, you will encounter 2 choice menus, each with 10 rows. You will find out your earnings for each of these menus as one of the rows is randomly selected. Please Note: We will use all rounds to determine your final earnings. Your total earnings will equal the sum of your earnings for the 2 menus.

Instructions Summary (ID = )

To summarize, you will indicate an option, A or B, for each of the rows by clicking on the “radio buttons” on the right side of the table.

Then a random number fixes which row of the table (i.e. which decision) is relevant for your earnings.

In that row, your decision fixed the choice for that row, Option A or Option B, and a final random number will determine the money payoff for the decision you made.

Appendix 2. Hypothetical Gamble Questions

A. Job Change Series

Suppose that you are the only income earner in the family. Your doctor recommends that you move because of allergies, and you have to choose between two possible jobs. The first would guarantee you an annual income for life that is equal to your parents’ current total family income. The second is possibly better paying, but the income is also less certain. There is a 50–50 chance the second job would double your total lifetime income and a 50–50 chance that it would cut it by a third. Which job would you take — the first job or the second job?

-

1.

First job

-

2.

Second job

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that the second job would double your lifetime income, and 50–50 that it would cut it in half. Would you take the first job or the second job?

-

1.

First job

-

2.

Second job

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that the second job would double your lifetime income and 50–50 that it would cut it by seventy-five percent. Would you take the first job or the second job?

-

1.

First job

-

2.

Second job

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that the second job would double your lifetime income and 50–50 that it would cut it by twenty percent. Would you take the first job or the second job?

-

1.

First job

-

2.

Second job

-

3.

Don't know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that the second job would double your lifetime income and 50–50 that it would cut it by 10 percent. Would you take the first job or the second job?

-

1.

First job

-

2.

Second job

-

3.

Do not know

B. Inheritance Series

Suppose that a distant relative left you a share in a private business worth one million dollars. You are immediately faced with a choice — whether to cash out now and take the one million dollars, or to wait until the company goes public in one month, which would give you a 50–50 chance of doubling your money to two million dollars and a 50–50 chance of losing one-third of it, leaving you 667 thousand dollars. Would you cash out immediately or wait until after the company goes public?

-

1.

Cash out

-

2.

Wait

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose that waiting a month, until after the company goes public, would result in a 50–50 chance that the money would be doubled to two million dollars and a 50–50 chance that it would be reduced by half, to 500 thousand dollars. Would you cash out immediately and take the one million dollars, or wait until the company goes public?

-

1.

Cash out

-

2.

Wait

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that waiting would double your money to two million dollars and 50–50 that it would reduce it by seventy-five percent, to 250 thousand dollars. Would you cash out immediately and take the one million dollars, or wait until after the company goes public?

-

1.

Cash out

-

2.

Wait

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose that waiting a month, until after the company goes public, would result in a 50–50 chance that the money would be doubled to two million dollars and a 50–50 chance that it would be reduced by twenty percent, to 800 thousand dollars. Would you cash out immediately and take the one million dollars, or wait until after the company goes public?

-

1.

Cash out

-

2.

Wait

-

3.

Do not know

Suppose the chances were 50–50 that waiting would double your money to two million dollars and 50–50 that it would reduce it by ten percent, to 900 thousand dollars. Would you cash out immediately and take the one million dollars, or wait until after the company goes public?

-

1.

Cash out

-

2.

Wait

-

3.

Do not know

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, L.R., Mellor, J.M. Are risk preferences stable? Comparing an experimental measure with a validated survey-based measure. J Risk Uncertain 39, 137–160 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-009-9075-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-009-9075-z